Abstract

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide with colorectal cancer (CRC) ranking as the third contributing to overall cancer mortality. Non-digestible compounds such as dietary fiber have been inversely associated with CRC in epidemiological in vivo and in vitro studies. In order to investigate the effect of fermentation products from a whole non-digestible fraction of common bean versus the short-chain fatty acid (SCFAs) on colon cancer cells, we evaluated the human gut microbiota fermented non-digestible fraction (hgm-FNDF) of cooked common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivar Negro 8025 and a synthetic mixture SCFAs, mimicking their concentration in the lethal concentration 50 (SCFA-LC50) of FNDF (hgm-FNDF-LC50), on the molecular changes in human colon adenocarcinoma cells (HT-29). Total mRNA from hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treated HT-29 cells were used to perform qPCR arrays to determine the effect of the treatments on the transcriptional expression of 84 genes related to the p53-pathway. This study showed that both treatments inhibited cell proliferation in accordance with modulating RB1, CDC2, CDC25A, NFKB and E2F genes. Furthermore, we found an association between the induction of apoptosis and the modulation of APAF1, BID, CASP9, FASLG, TNFR10B and BCL2A genes. The results suggest a mechanism of action by which the fermentation of non-digestible compounds of common bean exert a beneficial effect better than the SCFA mixture by modulating the expression of antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic genes in HT-29 cells to a greater extent, supporting previous results on cell behavior, probably due to the participation of other compounds, such as phenolic fatty acids derivatives and biopetides.

Keywords: Common bean, SCFA, Non-digestible fraction, Colorectal cancer, PCR-arrays

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality projected to increase in the future (WHO 2011). Cancer was considered a disease of westernized, industrialized countries. However, the situation has changed dramatically, with the majority of the global cancer burden now found in low- and medium-resource countries (Boyle and Levin 2008).

An inverse association between dietary fiber intake and CRC incidence has been shown in epidemiological studies (Dahm et al. 2010). Additionally, research on in vivo and in vitro models has shown the protective role of pulses, primarily due to the presence of indigestible compounds, such as phenolics (condensed tannins, flavonoids and anthocyanins), total dietary fiber (soluble and insoluble), and other secondary metabolites related to the prevention and/or reduction in chronic degenerative diseases (Bazzano et al. 2001; Beninger and Hosfield 2003; Waldecker et al. 2007). The resulting non-digestible fraction (NDF) (compounds that escaped degradation by intestinal enzymes) may reach the colon and can be fermented by the microbiota, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetic, propionic, butyric acids (Delzenne et al. 2003), as well as some phenolic SCFA derivatives formed during the intestinal degradation of phenolic constituents of vegetables and fruits (Waldecker et al. 2007). An optimal antitumor drug would be one which selectively induces apoptosis in tumoral but not in normal cells. There is enough evidence that butyric acid is an agent with such properties, which exerts a chemopreventive effect by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation, as well as inducing apoptosis resulting in a more differentiated phenotype (Sengupta et al. 2006), thus reducing the risk of developing CRC. The protection by SCFA has been studied using in vitro cell cultures, widely used to assess the effect of substances that may induce differentiation, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and DNA repair in transformed cells (Fu et al. 2004; Li and Li 2006).

It is well known that butyric acid is an important energy source for normal colonocytes (p53+) and maintains their growth and proliferation. However, this SCFA prevents the progression of cancer by inhibiting the growth, proliferation and survival of colorectal cells (p53−) (Ruemmele et al. 2003). The HT-29 cell line, derived from human colon adenocarcinoma, was established in 1975 (Fogh and Trempe 1975). Genetically, HT-29 cells present typical changes in colorectal tumors, such as APC, K-ras and p53 mutations and the consequent loss of their function, as well as amplification of c-myc (Rodrigues et al. 1990; Choi et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2009; Wu et al. 2010) and a phenotype of chromosomal instability and aneuploidy. This cell line has been used as a model to investigate the mechanism by which some protective compounds sensitize HT-29 cells to control of proliferation and apoptosis (Beyer-Sehlmeyer et al. 2003; Daly et al. 2005; Campos-Vega et al. 2010).

We previously demonstrated that compounds of common bean can inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in both in vivo and in vitro models by modulating the expression of genes involved in cell cycle arrest, cell proliferation and apoptosis (Feregrino-Pérez et al. 2008; Campos-Vega et al. 2010). Our previous study showed that common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Negro 8025 has fermentable substrates, such as the NDF (total dietary fiber, oligosaccharides, resistant starch and phenolic compounds), and the NDF was submitted to gut in vitro fermentation producing compounds that showed chemoprotective effect by inducing DNA fragmentation (apoptosis) and inhibiting the HT-29 cell survival (Cruz-Bravo et al. 2011). This investigation extends our previous study in evaluating the effect of the fermented non-digestible fraction (FNDF) of common bean (P. vulgaris L.) cultivar Negro 8025 on the modulation of p53-pathway-related gene expression in HT-29 cells, as well as showing that a complex of food compounds may exert a major effect in mutated p53 cells compared to chemoprotective agents separately. Also, we pretend to extend the knowledge on the mechanism of action of SCFA (mimicking their physiological produced concentrations during human gut microbiota fermentation) on colon cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Dry bean seeds

Beans of cultivar Negro 8025 were harvested in 2007 at the Bajio Experimental Station of the National Research Institute for Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock (INIFAP), located in Celaya, Guanajuato, Mexico. The seeds, cooked bean and the NDF were stored at 4 °C and protected from light.

Chemicals

Butyrate was purchased from Fluka™ (Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd., Oakville, ON, Canada; ≥99 %). Acetate, propionate (≥99.6 %) and other chemicals were purchased from J. T. Baker™ (Mexico City, Mexico). Protease, α-amylase and amyloglucosidase were obtained from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich, Canada Ltd.). Other chemicals were purchased from J. T. Baker™ (Mexico).

Non-digestible fraction extraction

Beans were cooked using a “traditional” cooking process according to the method of Aparicio-Fernandez et al. (2005). The AOAC method 991.43 (AOAC 2002) was used to obtain total dietary fiber (TDF) considered here as the NDF. Briefly, 1 g of each sample (uncooked and cooked) was placed in different Erlenmeyer flasks with 50 mL phosphate buffer (0.08 mol/L, pH 6) added and adjusted to pH 6 with 0.375 M HCl or 0.275 M-NaOH. Samples were placed in a water bath at 100 °C, and 0.1 mL a-amylase added to each and incubated for 30 min with manual stirring every 5 min. The flasks were cooled rapidly and the samples adjusted to pH 7.5. After the addition of 0.1 mL of protease (5 mg/mL phosphate buffer), samples were placed in a water bath at 60 °C for 30 min. Samples were cooled, and the samples’ pH was adjusted to pH 4. After pH adjustment, samples were placed in the water bath at 60 °C for 30 min, and 0.3 mL of amyloglucosidase was added. Samples were incubated for 30 min under constant agitation. Then, 95/100 mL ethanol at room temperature was added at a 1:4 sample/ethanol ratio, and the mixture left at room temperature for 24 h. Samples were filtered at a constant weight, and residues were washed tree times with 10 mL of distilled water. The residues were then placed in an oven at 90 °C for 2 h and weighed. The TDF was determined gravimetrically. After the results were corrected for protein and ash, it was considered as NDF. At least, three determinations of each treatment were conducted. To quantify insoluble dietary fiber (IDF), the ethanol was not added. The soluble dietary fiber (SDF) was calculated by subtracting the IDF proportion from TDF.

In vitro lower gastrointestinal fermentation

This study utilized a human gut flora fermentation method to estimate the effects of NDF digestion in the colon representing simulated large bowel model. It provides useful data to form hypotheses for in vitro studies. In vitro fermentation was done following by Campos-Vega et al. (2009) method. Fermentations were performed in duplicate for NDF extract from cooked bean in a water bath at 37 °C. Raffinose was used as a positive control for fermentable sugar under the same conditions. Human gut flora was collected from fecal sample supplied by one healthy volunteer who had no previous history of gastrointestinal disorders and had not undergone antibiotics therapy within 3 months prior to the study. Sterile tubes (15 mL) were filled with 9 mL of sterile basal culture medium containing (g/L): peptone water, 2; yeast extract, 2.0; NaCl, 0.1; K2HPO4, 0.04; KH2PO4, 0.04; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.01; CaCl2·2H2O, 0.01; NaHCO3, 2; cysteine HCl, 0.5; bile salts, 0.5; Tween-80, 2 mL; and hematin, 0.2 g (diluted in 5 mL of NaOH). Sealed tubes were maintained under a headspace containing H2–CO2–N2 (10:10:80, v/v/v); O2-free for 24 h. Human gut flora slurries were prepared by homogenizing 2 g of fresh stools with 18 mL of 0.1 M-sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7. The tubes containing basal culture medium were inoculated with 1 mL of fecal slurries, and the polysaccharides (100 mg) were added after inoculation, except for blanks. The samples were vortexed for 30 s and placed in a water bath at 37 °C. During fermentation, the pH of the sample and SCFAs production was assessed at 6, 12 and 24 h. Fermented extract was centrifuged (Hermle Z 323 K, Germany) at 4,500 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant (FE-hgf) was transferred to 1.5 mL tubes and placed in a freezer at −70 °C until bioassay.

Cell culture

Beans were cooked, and the NDF was extracted in order to perform the in vitro fermentation as described previously (Cruz-Bravo et al. 2011). HT-29 cells from a human colon adenocarcinoma of a Caucasian female containing mutated p53 purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) were grown and maintained in McCoy’s 5a medium (ATCC) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco™, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1 % antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco™, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 37 °C under 5 % CO2 air atmosphere. Subculture of HT-29 cell line was performed by enzymatic digestion (trypsin/EDTA solution: 0.05/0.02 %) (Sigma-Aldrich, Canada Ltd.). HT-29 cells were cultured in 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well under the growth conditions indicated above for 24 h. The medium was changed by adding McCoy’s 5a medium supplemented with bovine serum albumin (BSA Sigma–Aldrich(tm), Canada Ltd.) plus different concentrations (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35 %) of 100 % fermented NDF (previously sterilized by filtration). After incubation, cells were harvested. Hemocytometer counts were performed, and growth inhibition rate was plotted to determine lethal concentration 50 (LC50) value. Mc-Coy’s 5a medium containing 0.5 % BSA was also added to control cell culture. All data points were performed in duplicate, and each experiment was repeated independently at least twice for statistical analysis.

mRNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

According to our previous results (Cruz-Bravo et al. 2011), we considered the LC50 of hgf-FNDF (hgm-FNDF-LC50) and a mixture of synthetic SCFAs mimicking their concentration in the hgm-FNDF-LC50 (equivalent to 7.36, 0.33, and 3.31 mmol of acetic, propionic and butyric acids, respectively) to treat HT-29 cells in order to observe the effect of the fermented NDF extract from bean versus a mixture of SCFA on a colorectal cell line. The extraction of total mRNA from 2 × 106 treated and untreated cells was carried out using the RNeasy Mini Kit according to the Qiagen’s protocol. All mRNA samples were examined for the quality of the nucleic acid, that is, absence of DNA and mRNA degradation by denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis. For complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis, 230 ng mRNA was reverse transcribed and amplified with the SMART PCR cDNA synthesis kit and the Advantage cDNA PCR kit (CLONTECH Laboratories). The first-strand cDNA synthesis was done as specified in the manufacturers’ user manual and included total mRNA, the CDS synthesis primer, the SMART II oligonucleotide and Superscript II. The double-stranded cDNA was amplified with Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen), PCR primer (from the SMART PCR cDNA synthesis kit) using the following conditions: 95 °C 2 min and then 15 cycles of 94 °C-30 s/55 °C-30 s/72 °C-6 min.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

For quantitative determination of transcripts, 102 μL of diluted cDNA (100 ng/μL) was mixed with RT2 real-time™ SYBR Green/ROX PCR mastermix (PA-012, SABiosciences, Frederick, MD, USA), and the RT2 Profiler™ PCR array human p53 signaling pathway (96 well) (PAHS-027A, SABiosciences, USA) was used as specified in the manufacturers’ user manual. The human p53 signaling pathway RT2 Profiler™ PCR array shows the expression of 84 genes related to p53-mediated signal transduction involved in the processes of apoptosis, cell cycle, cell growth, proliferation, differentiation and DNA repair plus three housekeeping genes (B2M, GAPDH and ACTB). Real-time PCR was done using the Mx3005P QPCR system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) with the following protocol: 95 °C 10 min and then 40 cycles of 95 °C 15 s/60 °C 1 min. Data were evaluated with the MxProsoftware (Stratagene). To correct for well-to-well fluorescent fluctuations, normalization of the SYBR Green-dsDNA complex signal to the passive reference dye ROX (included in the SYBR Green PCR mastermix) was performed. Relative gene expression levels were calculated by the comparative Ct method including normalization to the constitutively expressed gene and to a control sample. Data were analyzed by PCR array data analysis web portal (http://www.sabioscience.com/pcr/arrayanalysis.php) based on the ΔΔCt method with normalization of the raw data to housekeeping genes. Excel-based data analysis template was used. Sequences as potential target genes were considered if the fold regulation between FNDF-LC50- or SCFA-LC50-treated and untreated HT-29 cells was greater than 2, following the instruction from data analysis web portal. Additionally, testing for overrepresentation of functional categories was carried out using database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery (DAVID) tools (da Huang et al. 2009). Categories were analyzed including gene ontology (GO) and kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) database.

Results and discussion

qPCR arrays were performed to profile the modulation of gene expression of 84 genes related to p53 pathway in treated and untreated HT-29 cells. Our results are presented as >twofold up- or down-regulated genes between hgm-FNDF-LC50- or SCFA-LC50-treated and untreated cells (Tables 1, 2) according to the data analysis obtained from the manufacturer’s software. However, we also considered some genes that were <twofold up- or down-regulated since their mRNA levels could be functionally relevant (Iacomino et al. 2001).

Table 1.

Up-regulated genes by hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments compared with untreated HT-29 cells

| Symbol | GenBank | Biological function | Fold regulation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hgm-FNDF-LC50 | SCFA-LC50 | |||

| Apoptosis | ||||

| APAF1 | NM_001160 | Induction of apoptosis | 108.38 | 3.24 |

| BID | NM_001196 | Induction of apoptosis | 32.00 | 19.12 |

| CASP2 | NM_032982 | Induction of apoptosis | 1.07 | 3.47 |

| CASP9 | NM_001229 | Induction of apoptosis | 12.73 | 3.88 |

| EI24 | NM_004879 | Induction of apoptosis | 8.57 | – |

| FASLG | NM_000639 | Induction of apoptosis | 2.13 | 4.55 |

| TNF | NM_000594 | Induction of apoptosis, cell proliferation, inflammatory response | 3.63 | – |

| TNFRSF10B | NM_003842 | Induction of apoptosis | 8.46 | 3.11 |

| GML | NM_002066 | Induction of apoptosis | 2.27 | 1.64 |

| Regulation of cell cycle | ||||

| ATR | NM_001184 | Negative regulation of cell cycle, DNA repair | 4.63 | 3.15 |

| BAI1 | NM_001702 | Inhibition of angiogenesis and growth | – | 6.90 |

| CCNE2 | NM_057749 | Cell cycle checkpoint | 7.94 | – |

| CCNG2 | NM_004354 | Cell cycle checkpoint | 3.86 | 5.30 |

| CHEK2 | NM_007194 | Cell cycle checkpoint | 1.64 | 3.52 |

| E2F3 | NM_001949 | Regulation of cell cycle | – | 3.20 |

| GADD45A | NM_001924 | Cell cycle arrest, DNA repair | 1.18 | 1.42 |

| NF1 | NM_000267 | Negative regulation of cell cycle | 4.66 | – |

| PCBP4 | NM_020418 | Negative regulation of cell cycle, induction of apoptosis | – | 2.23 |

| RB1 | NM_000321 | Cell cycle checkpoint | 3.36 | 2.26 |

| RPRM | NM_019845 | Negative regulation of cell cycle | 3.58 | 7.00 |

| SESN1 | NM_014454 | Negative regulation of cell cycle | 12.38 | 28.18 |

| SIRT1 | NM_012238 | Induction of apoptosis, negative regulation of cell cycle | 29.86 | 14.19 |

| TSC1 | NM_000368 | Negative regulation of the cell cycle | 1.78 | 10.32 |

| Cell proliferation | ||||

| IL6 | NM_000600 | Induction of inflammatory response and cell proliferation | 2.14 | 2.69 |

| KRAS | NM_004985 | Cell proliferation | 2.81 | 3.96 |

| MDM4 | NM_002393 | Negative regulation of cell proliferation | 6.06 | 3.55 |

| KAT2B | NM_003884 | Inhibition of cell growth | 3.12 | 12.79 |

| PPM1D | NM_003620 | Cell growth and anti-apoptosis | 4.44 | – |

| PRKCA | NM_002737 | Cell proliferation | 6.36 | 4.65 |

| TNFRSF10D | NM_003840 | Anti-apoptosis, cell survival | 1.82 | 4.49 |

| DNA repair | ||||

| MLH1 | NM_000249 | DNA repair genes | 2.06 | 3.31 |

| MSH2 | NM_000251 | DNA repair genes | 2.57 | 2.31 |

Results were normalized to housekeeping genes, and values represent the degree of changes in mRNA for treated HT-29 cells relative to untreated HT-29 cells. P = 0.05 compared with the control

– Not applicable

Table 2.

Down-regulated genes by hgm-NDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments compared with untreated HT-29 cells

| Symbol | GenBank | Biological function | Fold regulation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hgm-FNDF-LC50 | SCFA-LC50 | |||

| Regulation of apoptosis | ||||

| BAX | NM_004324 | Induction of apoptosis | −2.36 | −1.57 |

| BCL2 | NM_000633 | Anti-apoptosis | −1.25 | −1.37 |

| BCL2A1 | NM_004049 | Anti-apoptosis | −5.54 | −1.44 |

| BIRC5 | NM_001168 | Anti-apoptosis | −24.42 | – |

| CRADD | NM_003805 | Induction of apoptosis | −4.26 | −2.12 |

| ESR1 | NM_000125 | Induction of apoptosis, Inhibition of cell proliferation | −12.04 | −11.82 |

| FADD | NM_003824 | Induction of apoptosis | −2.11 | −1.54 |

| LRDD | NM_018494 | Induction of apoptosis | −2.23 | −1.56 |

| TP53AIP1 | NM_022112 | Induction of apoptosis | −4.82 | −1.88 |

| TP63 | NM_003722 | Induction of apoptosis | −1.02 | −3.93 |

| TRAF2 | NM_021138 | Anti-apoptosis | −2.85 | −1.63 |

| Regulation of cell cycle | ||||

| BTG2 | NM_006763 | Negative regulation of cell cycle and proliferation | −2.14 | −1.39 |

| CCNB2 | NM_004701 | Cell cycle checkpoint | −1.49 | −1.07 |

| CCNH | NM_001239 | Control of transcription and cell cycle | −1.69 | −4.45 |

| CDC2 | NM_001786 | Regulation of cell cycle | −3.16 | −9.15 |

| CDK4 | NM_000075 | Cell proliferation | −1.19 | −1.07 |

| CDKN2A | NM_000077 | Cell cycle arrest | −3.81 | – |

| CHEK1 | NM_001274 | Cell cycle checkpoint | −10.48 | −1.04 |

| E2F1 | NM_005225 | Regulation of cell cycle, apoptosis | −5.54 | −5.40 |

| E2F3 | NM_001949 | Regulation of cell cycle | −3.25 | – |

| IFNB1 | NM_002176 | Negative regulation of cell proliferation | −3.18 | −2.35 |

| IGF1R | NM_000875 | Regulation of cell cycle | −2.16 | – |

| MYOD1 | NM_002478 | Negative regulation of cell cycle, differentiation | −2.50 | −1.16 |

| NF1 | NM_000267 | Negative regulation of cell cycle | – | −3.69 |

| SESN2 | NM_031459 | Negative regulation of cell cycle | −3.23 | −2.13 |

| TADA3L | NM_006354 | Induction of apoptosis, negative regulation of cell cycle | −2.68 | −1.54 |

| TP53 | NM_000546 | Induction of apoptosis, negative regulation of cell cycle | −84.45 | −42.62 |

| TP73 | NM_005427 | Induction of apoptosis, negative regulation of cell cycle | −10.27 | −2.63 |

| WT1 | NM_000378 | Negative regulation of the cell cycle | −6.63 | −1.79 |

| Cell proliferation | ||||

| CDC25A | NM_001789 | Control of cell proliferation | −14.12 | −5.25 |

| CDC25C | NM_001790 | Control of cell proliferation | −6.32 | – |

| EGR1 | NM_001964 | Other genes related to cell growth, proliferation and differentiation | – | −2.30 |

| HK2 | NM_000189 | Cell proliferation | −2.79 | −3.17 |

| MDM2 | NM_002392 | Negative regulation of cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis | −24.42 | −30.55 |

| MYC | NM_002467 | Cell proliferation | −5.54 | −2.65 |

| NFKB1 | NM_003998 | Cell proliferation, anti-apoptosis | −25.11 | −12.41 |

| PRC1 | NM_003981 | Cell proliferation | −4.63 | −1.05 |

| STAT1 | NM_007315 | Regulation of apoptosis and cell proliferation | −3.39 | −2.61 |

| Cell growth and DNA repair | ||||

| BRCA1 | NM_007294 | Tumor suppressor gene, DNA repair | −20.11 | −8.19 |

| BRCA2 | NM_000059 | Tumor suppressor gene, DNA repair | −6.41 | −5.25 |

| DNMT1 | NM_001379 | Regulation of cytosine methylation | −17.39 | −32.30 |

| PPM1D | NM_003620 | Cell growth and anti-apoptosis | – | −2.09 |

| XRCC5 | NM_021141 | DNA repair genes | −2.23 | −4.67 |

Results were normalized to housekeeping genes, and values represent the degree of changes in mRNA for treated HT-29 cells relative to untreated HT-29 cells. P = 0.05 compared with the control

– Not applicable

Transcriptional regulation of cell cycle-related genes

Tumor can progress by defects in many molecules regulating cell cycle, such as p53 and other molecules controlling cell cycle progression. Rodrigues et al. (1990) showed that HT-29 cells have mutations that overproduce mutant p53, function associated with immortalization in vitro and in vivo development of cancer (Peralta-Zaragoza et al. 1997; Iacomino et al. 2001). Interestingly, this gene was the most down-regulated by both hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments in our study (−84.45- and −42.62-fold, respectively; Table 2). A similar effect was observed by Campos-Vega et al. (2010) after treatment by the fermented polysaccharide extract from common bean cultivar Bayo Madero in HT-29 cells, suggesting the modulation of mutated p53 as an inhibiting mechanism for non-digestible compounds of common bean in colon adenocarcinoma cells, and probably dependent of the cultivar since the effect of the hgm-FNDF-LC50 on this gene expression was in a lesser extent (−4.8).

On the other hand, cell survival in cancer progression is generally supported by several mechanisms, such as proliferation, lack of apoptosis, differentiation and DNA repair. During the transition from G1 to S phase, different substrates can be targeted by the cyclin-CDK complexes, such as the tumor suppressor Rb, which is associated with the transcription factor E2F. When the protein coded by its gene (pRb) is phosphorylated, E2F is released during the G1 phase and then participates in the transcription of several genes involved in cell cycle progress (Iacomino et al. 2001; Bai and Merchant 2001). In this study, the RB gene was induced (3.36- and 2.26-fold by hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments, respectively; Table 1), while E2F was inhibited by both treatments (−5.54- and −5.40-fold by hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments, respectively; Table 2) suggesting their participation in cell cycle control.

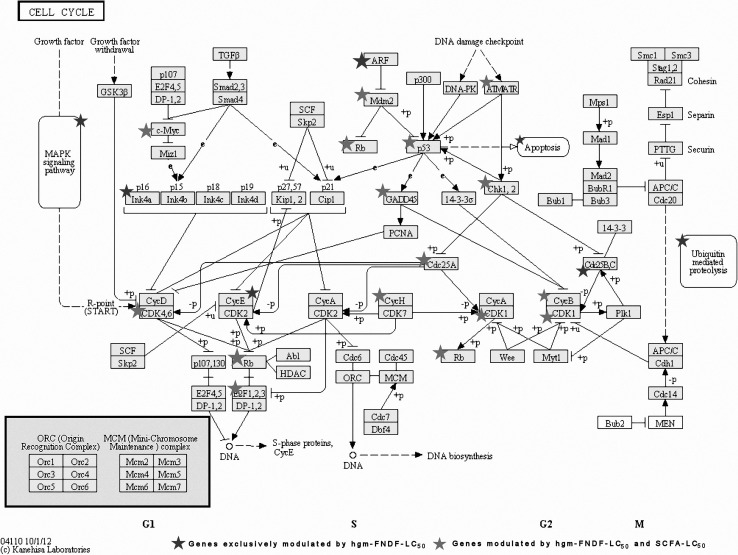

Furthermore, CDK4 that forms an active complex with Cyclin-D responsible for the first phosphorylation of tumor suppressor Rb in G1 (Zhang and Dean 2001) was down-regulated by both hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments (−1.19- and −1.07-fold, respectively; Table 2), suggesting a possible cell cycle arrest in G1–S phase. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of CDK proteins are other regulatory mechanisms for cell cycle progression. CDC25 removes inhibitory phosphates from specific tyrosine and threonine residues within the ATP-binding domain of the CDK proteins, thus activating these kinases. Overexpression of CDC25A plays a critical role in establishing transformed phenotypes, generally characterized by unrestricted cell cycle progression and/or suppressed cell death. The overexpression of CDC25A could also affect the responsiveness of cancer cells to oxidative and/or genotoxic stresses caused by cancer therapies (Iavarone and Massagué 1997). As cells approach M-phase (Fig. 1), the phosphatase CDC25A is activated and thus activates CDC2 (CDK1). In animals, CDC2 associates with an A- or B-type cyclin. The CDC2-cyclin B complex is able to establish a feedback amplification loop that efficiently drives the cell into mitosis (Zou et al. 2001). Its formation depends on the synthesis and proteolysis of the cyclin subunit and must enter the nucleus so that CDC2 is phosphorylated at threonine 161 by a kinase to be active (Mailand et al. 2002). On the other hand, CDC25 antagonizes the inhibitory phosphorylation of tyrosine 15 and threonine 14 of CDC2 at the G2/M boundary (Fesquet et al. 1993). Our results showed that hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments down-regulated both CDC25A (−14.12- and −5.25-fold, respectively; Table 2) and CDC2 (−3.16- and −9.15-fold, respectively; Table 2), suggesting that these treatments may have induced the cell cycle arrest in both G1–S and G2–M phases. Both treatments also down-regulated other genes (Table 2) related to proliferation, such as the transcription factor for cytokines STAT1 (−3.39- and −2.61-fold, respectively), PRC1 (−4.63- and −1.05-fold, respectively), which encodes a cell cycle protein that plays important roles during cytokinesis (Draetta and Eckstein 1997), as well as Hexokinase II (HK2) (−2.79- and −3.17-fold, respectively), involved in glycolysis, an essential process to maintain cell proliferation (34). Similar modulation was observed when HT-29 cells were treated with a fermented polysaccharide extract of common bean (P. vulgaris L.) cultivar Bayo Madero (Campos-Vega et al. 2010), supporting the suggesting inhibiting effect on cell cycle progression by derivative compounds of common bean fermentation.

Fig. 1.

Interaction among differentially modulated genes in the cell cycle biochemical pathway, using KEGG, after hgf-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments

SIRT1 belongs to sirtuin proteins with NAD+-dependent deacetylase activity; since this deacetylase can down-regulate the activity of NFκB, it can also be considered as anti-proliferative (Wolf et al. 2011). Furthermore, SIRT1 has been shown to inhibit colon cancer growth in mouse model (Yeung et al. 2004) and may be stimulated by polyphenols in HT-29 cells (Firestein et al. 2008). In our previous report, we showed that the hgm-FNDF has a residual content of phenolics (Cruz-Bravo et al. 2011), which is probably having a role in the effect by hgm-FNDF-LC50. In our study, SIRT1 was up-regulated by hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments (29.86- and 14.19-fold, respectively; Table 1), thereby implying that this gene may be a part of the mechanism by which the hgm-FNDF-LC50 inhibits HT-29 cells survival.

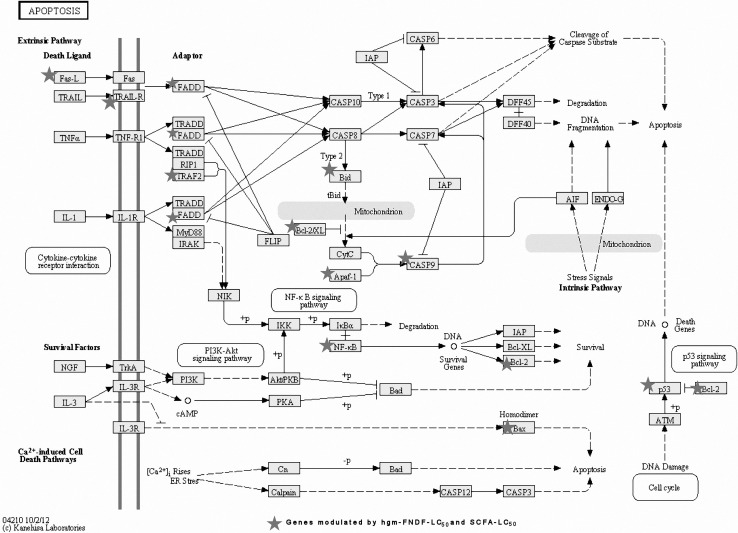

Transcriptional regulation of apoptosis and DNA repair-related genes

Programmed cell death (apoptosis) can be triggered by several molecules (Fig. 2), such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), a multifunctional proinflammatory cytokine considered as anti-cancer agent, playing important roles in several physiological and pathological processes by modulating growth arrest, differentiation and apoptosis (de Boer et al. 2006). For instance, TNFR1 (TNF Receptor-1) expressed by all human tissues is the major signaling receptor for TNF-α; when bound by TNF-α, this molecule forms a trimer and recruits an adaptor protein, TRADD, initiating the caspase cascade resulting in apoptosis (Basile et al. 2003). This receptor was up-regulated after both hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments (8.46- and 3.11-fold, respectively; Table 1); thereby representing one of the pathway, the colon adenocarcinoma cells under study can trigger cell death.

Fig. 2.

Interaction among differentially modulated genes in the apoptosis biochemical pathway, using KEGG, after hgf-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments

FASLG (up-regulated 2.13- and 4.55-fold by hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments, respectively; Table 1) is a ligand that can also induce apoptosis by binding to its receptor Fas on the surface of CRC cells (Yang et al. 2011). Some compounds, such as sodium butyrate, sensitize cancer cells (including HT-29) to p53-independent, Fas-mediated apoptosis (Bonnotte et al. 1998; Yang et al. 2012), suggesting this pathway as a mechanism for the treatments on the induction of extrinsic apoptosis by the treatments evaluated in this study. However, apoptosis may also be carried out through the mitochondrial pathway by several molecules such as the pro-apoptotic BID (up-regulated 32- and 19.12-fold by both treatments, respectively; Table 1). BID modifies the mitochondria by interacting with Bak and stimulates the opening of the mitochondrial membrane releasing Cytochrome-C to form the APAF-1 complex called apoptosome activating caspase 9 (CASP9), which triggers executioner caspases leading to apoptosis (Giardina et al. 1999). APAF-1 (the highest up-regulated gene by hgm-FNDF-LC50) is a key regulator of the mitochondrial apoptosis, and its transcriptional expression is lost or reduced in human colon adenocarcinoma cells, which implicates a poor prognosis, including poor differentiation, tumor invasion and metastasis (Henderson et al. 2003). Hence, therapies stimulating the expression of this gene are highly desirable. In this study, the up-regulation of both APAF-1 and CASP9 (108.38 and 3.24, respectively; 12.73- and 3.38-fold, respectively; Table 1) by hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments suggests their role in the induction of intrinsic apoptosis.

Another gene involved in apoptotic induction and cell cycle arrest is EI24 also known as PIG8. It is a DNA damage response gene located on human chromosome 11q23 in a region frequently altered in several human malignancies, and it suppresses cell growth by inducing apoptotic cell death (Paik et al. 2007). Although this gene is generally considered as a target of p53 transcription factor, it was up-regulated after hgm-FNDF-LC50 treatment (8.57-fold; Table 1) in the mutated p53-HT29 cells. Burns et al. (2001) found that under an apoptotic stimulation, EI24 mRNA level was not dependent on the presence of p53 in spleen of mice. Therefore, p53 is probably not playing a key role in apoptosis. Hence, we suggest that HT-29 cells death can be induced p53 independent.

In contrast, apoptosis can be inhibited by anti-apoptotic genes, such as BCL2A1 (suppressed 5.54 and 1.44 fold after hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments, respectively. Table 2), which blocks the caspase cascade by interacting with BAX. Furthermore, BCL2A1 expression can be induced by NFκB, and it contains a binding site for NFκB stimulating its activity (Chen et al. 2004). The inhibition of this gene by antitumor compounds in foods including common bean has been previously demonstrated (Feregrino-Pérez et al. 2008; Campos-Vega et al. 2010).

The complex TNF-α and TRADD can also bind to TRAF2 protein, to transmit the TNF-α signal through NFκB (widely known to support cancer progression). The protein encoded by the latter is an important regulator in cell fate decisions by the programmed cell death and proliferation control, and is critical in tumorigenesis (Basile et al. 2003). Furthermore, it can be activated by exposure of cells to inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, oxidant-free radicals and other stimuli. Complete and persistent inhibition of NFκB has been linked directly to apoptosis and delayed cell growth (H-Zadeh et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2010). Down-regulation of both TRAF2 and NFκB by hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments (−2.85- and −1.63-fold, respectively; −25.11- and −12.41-fold, respectively; Table 2) implies that these genes may be involved in the proliferation inhibition of HT-29 cells. The apoptotic process can also be inhibited by other molecules called inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), such as BIRC5 (also known as Survivin), (down-regulated 24.42-fold after hgm-FNDF-LC50 treatment; Table 2), which may also be under-expressed in HT-29 cells in response to butyrate (Daly et al. 2005).

Nevertheless, we found contradictory results in this study, such as the induction of genes that support cell survival (CCNE2, CCNG2, E2F3, IL6, KRAS; Table 1), and the suppression of BAX and ESR1 (Table 2) and the transcriptional expression of DNA repair genes, such as MSH2 (2.57- and 2.31-fold), MLH1 (2.06- and 3.31-fold), ATR (4.63- and 3.15-fold) and GADD45A (1.18- and 1.42-fold) were also induced by both hgm-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 treatments, respectively. These results are comparable with those reported previously in CRC cell lines treated with butyrate and other chemopreventive compounds (Daly et al. 2005; Campos-Vega et al. 2010). These results correspond to conditions where cell responds to cytotoxic drugs by activating a physiological cell growth inhibition, or trying to recover from it, as suggested between pro- and anti-apoptotic events (Iacomino et al. 2001). Moreover, we observed up-regulation of some genes only after treatment with hgm-FNDF-LC50, not so with the SCFA-LC50 (Tables 1, 2). In our previous report (Cruz-Bravo et al. 2011), we showed that the hgm-FNDF-LC50 also contains phenolic compounds and probably some biopeptides, suggesting a synergistic effect influenced by the whole hgm-FNDF-LC50 on the HT-29 cells. Hence, diet composition may influence the CRC progression through several mechanisms (Johnson 2004).

Biological significance

Gene ontology (GO) term overrepresentation analyses were performed for FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 groups independently using the DAVID annotation analysis system (da Huang et al. 2009) and identified term enrichment for biological processes. Of important note, the FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50 gene sets exhibited similar maximally enriched processes, with “regulation of apoptosis” dominating and statistically significant. In addition to the regular GO overrepresentation analysis, DAVID provides a clustering function that forms sets of overlapping gene categories, highlighting “regulation of apoptosis” followed by “cell cycle” for the two categories (Table 3).

Table 3.

Functional clustering of gene annotations using the DAVID resource reveals enrichment for genes involved in apoptosis in both treatments gene set (hgf-FNDF-LC50 and SCFA-LC50, respectively)

| Category | Term | Count | P value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top cluster for the set of hgm-FNDF-LC 50 target genes | ||||

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Regulation of apoptosis | 37 | 3.3E−27 | 5.5E−24 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Regulation of programmed cell death | 37 | 4.6E−27 | 7.7E−24 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Regulation of cell death | 37 | 5.3E−27 | 8.8E−24 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Apoptosis | 33 | 4.0E−26 | 6.7E−23 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Programmed cell death | 33 | 6.4E−26 | 1.1E−22 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Cell death | 33 | 1.0E−23 | 1.7E−20 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Death | 33 | 1.2E−23 | 2.1E−20 |

| SP_PIR_KEYWORDS | Apoptosis | 23 | 1.5E−21 | 1.8E−18 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Positive regulation of apoptosis | 23 | 3.1E−17 | 5.2E−14 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Positive regulation of programmed cell death | 23 | 3.6E−17 | 6.0E−14 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Positive regulation of cell death | 23 | 4.0E−17 | 6.6E−14 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Induction of apoptosis | 19 | 8.2E−15 | 1.4E−11 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Induction of programmed cell death | 19 | 8.7E−15 | 1.4E−11 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Induction of apoptosis by intracellular signals | 10 | 4.0E−12 | 6.6E−9 |

| Top cluster for the set of SCFA-LC 50 target genes | ||||

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Regulation of apoptosis | 37 | 3.3E−27 | 5.5E−24 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Regulation of programmed cell death | 37 | 4.6E−27 | 7.7E−24 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Regulation of cell death | 37 | 5.3E−27 | 8.8E−24 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Apoptosis | 33 | 4.0E−26 | 6.7E−23 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Programmed cell death | 33 | 6.4E−26 | 1.1E−22 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Cell death | 33 | 1.0E−23 | 1.7E−20 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Death | 33 | 1.2E−23 | 2.1E−20 |

| SP_PIR_KEYWORDS | Apoptosis | 23 | 1.5E−21 | 1.8E−18 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Positive regulation of apoptosis | 23 | 3.1E−17 | 5.2E−14 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Positive regulation of programmed cell | 23 | 3.6E−17 | 6.0E−14 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Positive regulation of cell death | 23 | 4.E−17 | 6.6E−14 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Induction of apoptosis | 19 | 8.2E−15 | 1.4E−11 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Induction of programmed cell death | 19 | 8.7E−15 | 1.4E−11 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | Induction of apoptosis by intracellular signals | 10 | 4.0E−12 | 6.6E−9 |

Conclusions

In the present study, we showed that the exposure of HT-29 cells to fermented specific extract from common bean cv Negro 8025 results in the modulating gene expression related with apoptosis and cell cycle; most of the genes analyzed were regulated by SCFA-LC50 to a lesser extent, compared to the hgm-FNDF-LC50, supporting previous results on cell behavior, probably due to the participation of other compounds, such as phenolic fatty acids derivatives and biopetides. This suggests that a variety of compounds from the fermentation of the NDF of foods are more effective in controlling cell cycle and apoptosis in CRC cells than bioactive compounds separately. As a whole, we demonstrate that common bean (P. vulgaris L.) cultivar Negro 8025 has an inhibiting effect against CRC cells by evaluating its human gut fermented NDF and its modulation on genes involved in p53-related signaling pathways, such as the regulation of apoptosis and cell cycle in human colon adenocarcinoma HT-29 cells. Until our knowledge, it is the first time where the human gut fermented NDF of common bean is compared with their corresponded synthetic SCFA mixture, mimicking their physiological produced concentrations during human gut microbiota fermentation, some of the most studied compounds on colon cancer protection, on the modulation of gene expression by array approach.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed at Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (PARC-AAFC), Summerland, British Columbia, Canada and financially supported in part by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT), Grant 57436. The authors wish to thank Virginia Dickison for technical support.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

References

- Aparicio-Fernandez X, Manzo-Bonilla L, Loarca-Pina GF. Comparison of antimutagenic activity of phenolic compounds in newly harvested and stored common beans Phaseolus vulgaris against aflatoxin B1. J Food Sci. 2005;70:S73–S78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb09068.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Official methods of analysis. 17. Arlington, VA: AOAC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Merchant JL. ZBP-89 promotes growth arrest through stabilization of p53. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4670–4683. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4670-4683.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile JR, Eichten A, Zacny V, Münger K. NF-κB-mediated induction of p21Cip1/Waf1 by tumor necrosis factor A induces growth arrest and cytoprotection in normal human keratinocytes. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:262–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzano L, He J, Ogden L, Loria C, Vupputuri S, Myers L, Whelthon P. Legume consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in US men and women. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2573–2578. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.21.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beninger CW, Hosfield GL. Antioxidant activity of extracts, condensed tannin fractions, and pure flavonoids from Phaseolus vulgaris L. seed coat color genotypes. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:7879–7883. doi: 10.1021/jf0304324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer-Sehlmeyer G, Glei M, Hartmann E, Hughes R, Persin C, Bohm V, Rowland I, Schubert R, Jahreis G, Pool-Zobel BL. Butyrate is only one of several growth inhibitors produced during gut flora-mediated fermentation of dietary fibre sources. Br J Nutr. 2003;90:1057–1070. doi: 10.1079/BJN20031003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnotte B, Favre N, Reveneau S, Micheau O, Droin N, Garrido C, Fontana A, Chauffert B, Solary E, Martin F. Cancer cell sensitization to Fas-mediated apoptosis by sodium butyrate. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:480–487. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle P, Levin B. World cancer report 2008. Lyon: WHO-IARC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Bernhard E, El-Deiry W. Tissue specific expression of p53 target genes suggests a key role for KILLER/DR5 in p53-dependent apoptosis in vivo. Oncogene. 2001;20:4601–4612. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Vega R, Reynoso-Camacho R, Pedraza-Aboytes RG, Acosta-Gallegos JA, Guzman- Maldonado SH, Paredes-Lopez O, Oomah BD, Loarca-Piña G. Chemical composition and in vitro polysaccharide fermentation of different beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) J Food Sci. 2009;74:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Vega R, Guevara-Gonzalez RG, Guevara-Olvera LB, Oomah D, Loarca-Piña G. Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) polysaccharides modulate gene expression in human colon cancer cells (HT-29) Food Res Int. 2010;47:1057–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2010.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GG, Liang NC, Lee JF, Chan UP, Wang SH, Leung BCS, Leung KL. Over-expression of Bcl-2 against Pteris semi pinnata L-induced apoptosis of human colon cancer cells via a NF-kappa B-related pathway. Apoptosis. 2004;9:619–627. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000038041.57782.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi IK, Kim YH, Kim JS, Seo JH. PPAR-γ ligand promotes the growth of APC-mutated HT-29 human colon cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Invest New Drugs. 2008;26:283–288. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Bravo RK, Guevara-Gonzalez RG, Ramos-Gomez M, Garcia-Gasca T, Campos-Vega R, Oomah B, Loarca-Piña G. Fermented non-digestible fraction from common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivar negro 8025 modulates HT-29 cell behavior. J Food Sci. 2011;76:41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahm CC, Keogh RH, Spencer EA, Greenwood DC, Key TJ, Fentiman IS, Shipley MJ, Bruner EJ, Cade JE, Burley VJ, Mishra G, Stephen AM, Kuh D, White IR, Luben R, Lentjes MAH, Khaw KT. Dietary fiber and colorectal cancer risk: a nested case-control study using food diaries. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:614–626. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly K, Cuff MA, Fung F, Shirazi-Beechey SP. The importance of colonic butyrate transport to the regulation of genes associated with colonic tissue homoeostasis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:733–735. doi: 10.1042/BST0330733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer V, de Goffau MC, Arts IC, Hollman PC, Keijer J. SIRT1 stimulation by polyphenols is affected by their stability and metabolism. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:618–627. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delzenne N, Cherbut C, Neyrinck A. Prebiotics: actual and potential effects in inflammatory and malignant colonic diseases. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;6:581–586. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200309000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draetta G, Eckstein J. Cdc25 protein phosphatases in cell proliferation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1332:53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(96)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feregrino-Pérez AA, Berumen LC, Garcia-Alcocer G, Guevara-Gonzalez RG, Ramos-Gomez M, Reynoso-Camacho R, Acosta-Gallegos JA, Loarca-Piña G. Composition and chemopreventive effect of polysaccharides from common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on azoxymethane-induced colon cancer. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:8737–8744. doi: 10.1021/jf8007162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fesquet D, Labbe JC, Derancourt J, Capony JP, Galas S, Girard F, Lorca T, Shuttleworth J, Doree M, Cavadore JC. The MO15 gene encodes the catalytic subunit of a protein kinase that activates cdc2 and other cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) through phosphorylation of Thr161 and its homologues. EMBO J. 1993;12:3111–3121. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestein R, Blander G, Michan S, Oberdoerffer P, Ogino S, Campbell J, Bhimavarapu A, Luikenhuis S, de Cabo R, Fuchs C, Hahn WC, Guarente LP, Sinclair DA. The SIRT1 deacetylase suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis and colon cancer growth. PLoS ONE. 2008 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogh J, Trempe G. New tumor cell lines. In: Fogh J, editor. Human tumor cells in vitro. 1. New York: Plenum Publishing Corp; 1975. pp. 115–141. [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Shi YQ, Mo SJ. Effect of short-chain fatty acids on the proliferation and differentiation of the human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line Caco-2. Chin J Dig Dis. 2004;5:115–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2004.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardina C, Boulares H, Inan MS. NSAIDs and butyrate sensitize a human colorectal cancer cell line to TNF-alpha and Fas ligation: the role of reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1448:425–438. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(98)00156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C, Mizzau M, Paroni G, Maestro R, Schneider C, Brancolini C. Role of caspases, Bid, and p53 in the apoptotic response triggered by histone deacetylase inhibitors trichostatin-A (TSA) and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12579–12589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- H-Zadeh AM, Collard TJ, Malik K, Hicks DJ, Paraskeva C, Williams AC. Induction of apoptosis by the 16-kDa amino-terminal fragment of the insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 in human colonic carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:1279–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacomino G, Tecce MF, Grimaldi C, Tosto M, Russo GL. Transcriptional response of a human colon adenocarcinoma cell line to sodium butyrate. Biochem Biophys Res Co. 2001;285:1280–1289. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavarone A, Massagué J. Repression of the CDK activator Cdc25A and cell-cycle arrest by cytokine TGF-beta in cells lacking the CDK inhibitor p15. Nature. 1997;387:417–422. doi: 10.1038/387417a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson IT. New approaches to the role of diet in the prevention of cancers of the alimentary tract. Mutat Res. 2004;551:9–28. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li RW, Li CJ. Butyrate induces profound changes in gene expression related to multiple signal pathways in bovine kidney epithelial cells. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:234–248. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Sakamaki T, Casimiro MC, Willmarth N, Quong AA, Ju X, Ojeifo J, Jiao X, Yeow WS, Katiyar S, Shirley LA, Joyce D, Lisanti MP, Albanese C, Pestell RG. The canonical NF-κB pathway governs mammary tumorigenesis in transgenic mice and tumor stem cell expansion. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10464–10473. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailand N, Podtelejnikov AV, Groth A, Mann M, Bartek J, Lukas J. Regulation of G2/M events by Cdc25A phosphatase through phosphorylation-dependent modulation of its stability. EMBO J. 2002;21:5921–5929. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik SS, Jang KS, Song YS, Jang SH, Min KW, Han HX, Na W, Lee KH, Choi D, Jang SJ. Reduced expression of Apaf-1 in colorectal adenocarcinoma correlates with tumor progression and aggressive phenotype. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3453–3459. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta-Zaragoza O, Bahena-Román M, Madrid-Marina V. Regulación del ciclo celular y desarrollo del cáncer: perspectivas terapéuticas. Salud Publica Mex. 1997;39:451–462. doi: 10.1590/S0036-36341997000500008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues NR, Rowan A, Smith ME, Kerr IB, Bodmer WF, Gannon JV, Lane DP. p53 mutations in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7555–7559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruemmele FM, Schwartz S, Seidman EG, Dionne S, Levy E, Lentze MJ. Butyrate induced Caco-2 cell apoptosis is mediated via the mitochondrial pathway. Gut. 2003;52:94–100. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Does butyrate protect from colorectal cancer? J Gastroen Hepatol. 2006;21:209–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. Mammalian G1 cyclins. Cell. 1993;73:1059–1065. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90636-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldecker M, Kautenburger T, Daumann H, Busch C, Schrenk D. Inhibition of histone-deacetylase activity by short-chain fatty acids and some polyphenol metabolites formed in the colon. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;19:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A, Agnihotri S, Micallef J, Mukherjee J, Sabha N, Cairns R, Hawkins C, Guha A. Hexokinase 2 is a key mediator of aerobic glycolysis and promotes tumor growth in human glioblastoma multiforme. J Exp Med. 2011;208:313–326. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2011) Cancer fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/index.html. Accessed 15 June 2011

- Wu CH, Shih YW, Chang CH, Ou TT, Huang CC, Hsu JD, Wan CJ. EP4 upregulation of Ras signaling and feedback regulation of Ras in human colon tissues and cancer cells. Arch Toxicol. 2010;84:731–740. doi: 10.1007/s00204-010-0562-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Luo C, Cai J, Powell DW, Yu D, Kuehn MH, Tezel G. Neurodegenerative and Inflammatory Pathway components linked to TNF-α/TNFR1 signaling in the glaucomatous human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:8442–8454. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Liu HZ, Fu ZX. PEG-liposomal oxaliplatin induces apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells via Fas/FasL and caspase-8. Cell Biol Int. 2012;36:289–296. doi: 10.1042/CBI20100825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, Keller MD, Jones DR. Modulation of NF-κB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 2004;23:2369–2380. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Dean D. Rb-mediated chromatin structure regulation and transcriptional repression. Oncogene. 2001;20:3134–3138. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Ge YL, Tian RH. The knockdown of c-myc expression by mRNAi inhibits cell proliferation in human colon cancer HT-29 cells in vitro and in vivo. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2009;14:305–318. doi: 10.2478/s11658-009-0001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X, Tsutsui T, Ray D, Blomquist JF, Ichijo H, Ucker DS, Kiyokawa H. The cell cycle-regulatory CDC25A phosphatase inhibits apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4818–4828. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4818-4828.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]