Abstract

Ovarian cancer is a leading cause of cancer deaths among women. Effective targets to treat advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) and biomarkers to predict treatment response are still lacking because of the complexity of pathways involved in ovarian cancer progression. Here we show that miR-181a promotes TGF-β-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via repression of its functional target, Smad7. miR-181a and phosphorylated Smad2 are enriched in recurrent compared with matched-primary ovarian tumours and their expression is associated with shorter time to recurrence and poor outcome in patients with EOC. Furthermore, ectopic expression of miR-181a results in increased cellular survival, migration, invasion, drug resistance and in vivo tumour burden and dissemination. In contrast, miR-181a inhibition via decoy vector suppression and Smad7 re-expression results in significant reversion of these phenotypes. Combined, our findings highlight an unappreciated role for miR-181a, Smad7, and the TGF-β signalling pathway in high-grade serous ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer is often diagnosed at a late stage when metastasis has already occurred. In this study, Parikh et al. show that mir-181a is involved in mediating the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in ovarian cancer, leading to activation of the TGF-β signalling pathway and metastasis.

Ovarian cancer is often diagnosed at a late stage when metastasis has already occurred. In this study, Parikh et al. show that mir-181a is involved in mediating the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in ovarian cancer, leading to activation of the TGF-β signalling pathway and metastasis.

In the United States, ~22,300 women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer and ~15,500 die from the disease every year1. Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), which accounts for ~90% of all ovarian cancers, has the highest mortality rate among all gynaecological malignancies. This is primarily due to advanced stage at diagnosis and the recurrence of chemotherapy-resistant tumours, resulting in poor overall survival (OS) in the majority of patients1,2. An incomplete understanding of the molecular pathways that regulate disease development poses a major challenge to improving clinical outcome. Hence, elucidating functionally relevant molecular drivers of ovarian cancer progression is crucial for the development of targeted therapy that can help improve survival outcomes in affected patients.

Recent data from large-scale analysis of numerous high-grade serous ovarian cancer samples suggests that acquisition of invasiveness in ovarian cancer cells is accompanied by the emergence of a mesenchymal subtype of tumours with a transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) gene signature that is associated with poor patient outcome3. The driving molecular events behind the mesenchymal subtype in ovarian cancer, however, remain poorly understood. TGF-β is a multifunctional protein that can function either as a tumour suppressor or as a promoter, depending on cellular context. Typically, in cancer cells, TGF-β has been shown to induce epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which plays a critical role in metastasis and is associated with chemotherapy resistance in numerous cancers. EMT is characterized by loss of epithelial morphology and cytoskeletal reorganization rendering epithelial cells more motile and invasive. Although several studies have uncovered an association between EOC outcome and TGF-β-mediated EMT, the mechanism by which TGF-β signalling is modulated in the disease and the functional relevance of this pathway remain unknown.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, non-coding RNA molecules that negatively regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level in a sequence-specific manner, primarily via base pairing to the 3′-untranslated region (3′UTR) of the target messenger RNA transcripts. Mounting evidence implicates miRNAs as regulators of the tumour phenotype through their ability to modulate the expression of critical genes and signalling networks involved in tumorigenesis and downstream malignant processes3,4. Numerous miRNA profiling studies in EOC have identified miRNAs associated with chemotherapy resistance and disease progression5,6,7,8,9,10. In a study analysing 443 advanced EOC specimens from The Cancer Genome Atlas, it was found that high expression of miR-181a was associated with shorter recurrence time (23 versus 59 months, P=0.013), possibly implicating a significant role for this miRNA in ovarian cancer pathogenesis11. In addition, miR-181a expression is shown to be regulated by numerous signalling networks, including TGF-β, MYC, oestrogen, STAT3 and Wnt/β-catenin, indicating a potential role in regulating cancer-relevant signalling pathways12,13,14,15,16. Lastly, miR-181a-1 resides in the 1q ‘hotspot’ region of gain (1q31.3–1q32.1)17, which is overexpressed in ovarian carcinomas compared with normal tubal and ovarian surface epithelia18. However, the functional relevance of this miRNA in ovarian cancer progression has been unknown.

In this study, we identify miR-181a as an inducer of TGF-β-mediated EMT, via suppression of Smad7, in ovarian cancer and define a unique mechanism by which the TGF-β signalling pathway is activated in EOC tumours. Our data highlight a functional role for miR-181a in ovarian cancer biology and uncover a potential prognostic biomarker and molecular target for the treatment of EOC.

Results

Elevated expression of miR-181a in advanced-stage EOC

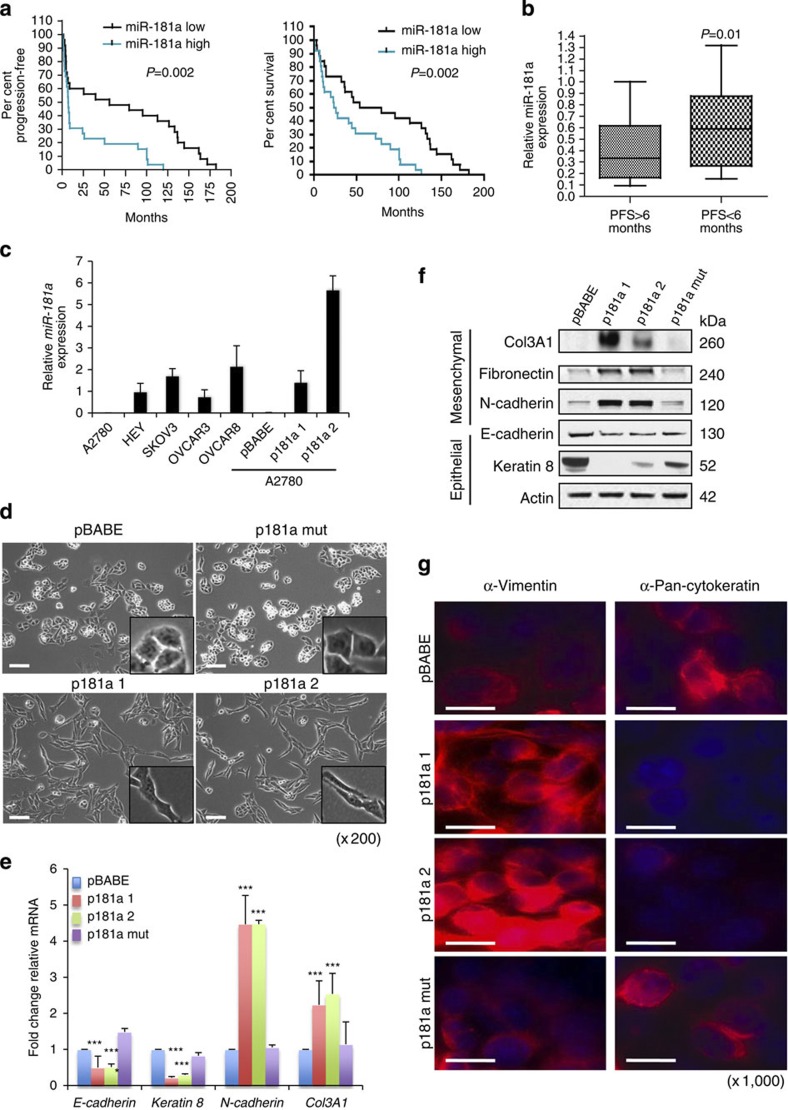

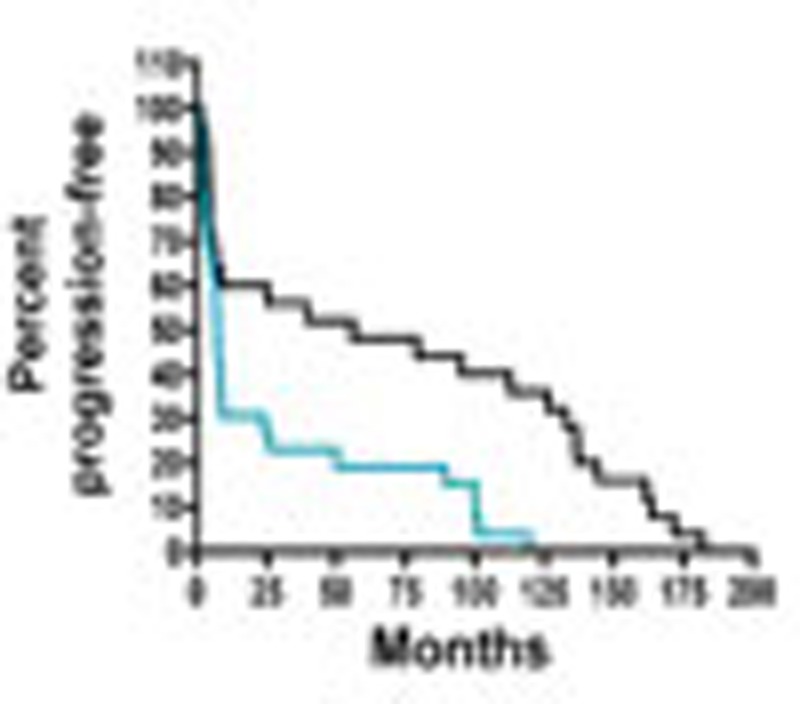

To assess the clinical relevance of miR-181a in EOC, we analysed its expression in a clinically annotated patient cohort of high-grade stage-III primary papillary serous ovarian cancer (Supplementary Table S1) by Taqman-based real-time quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (qRT–PCR). Using the median expression value of miR-181a as a cutoff point, the cohort was dichotomized into miR-181a-high- or miR-181a-low-expressing tumours. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 59.9 months for patients with low miR-181a expression, whereas in patients with high levels of miR-181a the median PFS was 7.1 months (Fig. 1a, P=0.002, odds ratio (OR): 7.8, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 7.2–8.4, log-rank Mantel–Cox test). Furthermore, patients with low miR-181a levels exhibited a median OS of 66.6 months in contrast to a median OS of 24.9 months in patients with high expression levels of miR-181a (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table S2, P=0.002, OR: 2.7, 95% CI: 2.1–3.3, log-rank Mantel–Cox test). In addition, tumours of patients with PFS<6 months (clinically described as platinum resistant) had higher expression of miR-181a (P=0.01, two-tailed Student’s t-test) when compared with patients with PFS>6 months (platinum sensitive; Fig. 1b). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the clinicopathological features of these two groups (Supplementary Table S1). Given that miR-181a belongs to a miRNA family that consists of miR-181a, -b, -c and -d, we also analysed the expression of all four miR-181 family members in our clinically annotated patient cohort. Only miR-181a and -b were readily detectable in all patient samples. Consistent with the fact that these two miRNAs are transcribed as a single polycistronic transcript from the same chromosomal locations, similar to miR-181a, miR-181b also showed a correlation with patient outcome (Supplementary Fig. S1). Interestingly, other miRNAs previously reported to be overexpressed in EOC, specifically miR-183 and miR-203, did not have similar correlations with clinical outcomes in our patient cohort19 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Taken together, these data support the association between high miR-181a expression and poor patient outcome. Given that miRNA gene families that are coexpressed from the same cluster and share the same seed region tend to have redundant biological functions and regulate the same sets of target genes, we focused on elucidating the biological effect of miR-181a.

Figure 1. miR-181a levels are associated with poor outcome and shorter time to recurrence in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer.

(a) Kaplan–Meier curves for PFS (left) and OS (right) in a cohort of patients (n=53) with stage-III primary ovarian serous adenocarcinoma according to relative expression levels of miR-181a (dichotomized at the median). P-values determined by log-rank statistical test. (b) Relative miR-181a levels in patient tumour specimens with PFS<6 months versus PFS>6 months (P=0.01, log-rank statistical test). (c) qRT–PCR analysis showing relative miR-181a expression levels in a panel of ovarian cancer cell lines and in A2780 p181a 1 and 2 cells. (n=3) Error bars, s.d. (d) Phase-contrast microscopic images of miR-181a-overexpressing cells versus control pBABE cells (original magnification, × 200, scale bars, 20 μM (white)). (e) Changes in the expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers in miR-181a-overexpressing cells as measured by qRT–PCR. Student’s t-test, ***P≤0.001 (n=3). Error bars, s.d. and (f) western blotting. (g) Effects of miR-181a on pan-cytokeratin and vimentin (both in red (Texas Red) and blue (DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole)) expression as evaluated by immunoflourescence (original magnification, × 1,000, scale bars, 5 μM (white)).

miR-181a promotes EMT transition

Given the clinical evidence of its association with both poor PFS and OS, we assessed the functional role of miR-181a in ovarian cancer biology. We stably expressed miR-181a (p181a), an empty vector (pBABE) and a vector expressing a mutant form of miR-181a (p181a mut) in the A2780 cell line (derived from chemotherapy-naive primary epithelial ovarian tumour), which expresses the lowest relative levels of miR-181a compared with a panel of ovarian cancer cell lines and primary patient samples. The miR-181a expression in the two independently derived polyclonal pools of miR-181a-transduced cells (p181a 1 and p181a 2) was comparable to the basal expression in the other ovarian cancer cell lines, as well as patient samples (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. S3). Functional assessment of the exogenous miR-181a was achieved using lentiviral-based miRNA sensor vectors carrying the mCherry reporter gene with either four miR-181a-binding sites in the 3′UTR or no binding site, serving as a transduction control. Only p181a 1 and p181a 2 cells exhibited strong downregulation of reporter expression when infected with the mCherry-based miR-181a sensor, confirming enhanced expression of functionally active miR-181a (Supplementary Fig. S4). Ectopic expression of miR-181a resulted in a fibroblast-like mesenchymal appearance of cells with loss of epithelial features consistent with EMT (Fig. 1d). These morphological features were consistent with defined molecular alterations that occur during the induction of EMT as demonstrated by decreased expression of epithelial markers, E-cadherin and keratin 8, and a concomitant increase in the expression of mesenchymal markers, N-cadherin, fibronectin and Col3A1 (Fig. 1e,f). In addition, immunofluorescence staining for pan-cytokeratin and vimentin further supports miR-181a’s ability to induce EMT; the miR-181a-expressing cells have significantly higher vimentin expression and lower pan-cytokeratin staining compared with both the pBABE and p181a mut cells (Fig. 1g). The miR-181a-induced EMT-like features were also observed in an additional ovarian serous adenocarcinoma cell line, HEY (Supplementary Fig. S5).

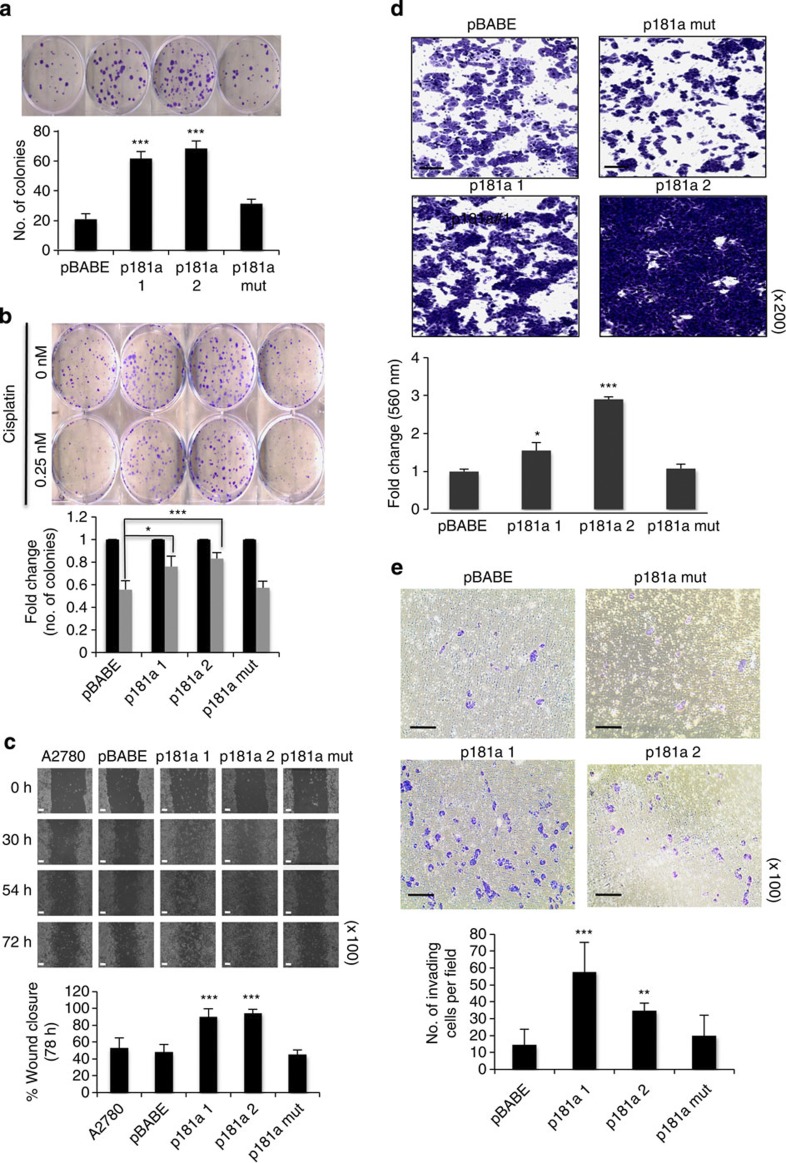

EMT plays an important role in cell motility, cellular survival, drug response and tumour dissemination in vivo; therefore, we next assessed whether miR-181a-induced EMT affected these biological processes. Colony-formation assay revealed that enhanced miR-181a expression increased cellular survival and conferred platinum resistance without affecting cell proliferation (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. S6). In addition, wound-healing, transwell migration and invasion assays showed that miR-181a overexpression significantly increased cellular motility and invasion (Fig. 2c–e).

Figure 2. Enhanced expression of miR-181a increases migration and invasion.

(a) Clonogenic assay to assess the effects of miR-181a on cellular survival (b) and response to cisplatin. Colonies are shown in purple post staining with crystal violet (top). Student’s t-test, *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01 and ***P≤0.001 (n=3); NS, not significant. Error bars, s.d. (c) Wound-healing assay (top) to assess the effects of miR-181a on cellular motility by calculating per cent wound closure over time points shown (bottom). Original magnification, × 100, scale bars, 100 μM (white). Student’s t-test, ***P≤0.001 are shown (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (d) Additional assessment of the migratory potential using a transwell migration assay (four panels on top). Original magnification, × 200, scale bars, 50 μM (black). Student’s t-test, *P≤0.05 and ***P≤0.001 (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (e) Transwell invasion assay of miR-181a-expressing cells compared with control cell lines (four panels on top). Original magnification, × 100, scale bars, 100 μM (black). Student’s t-test, **P≤0.01 and ***P≤0.001 (n=3). Error bars, s.d.

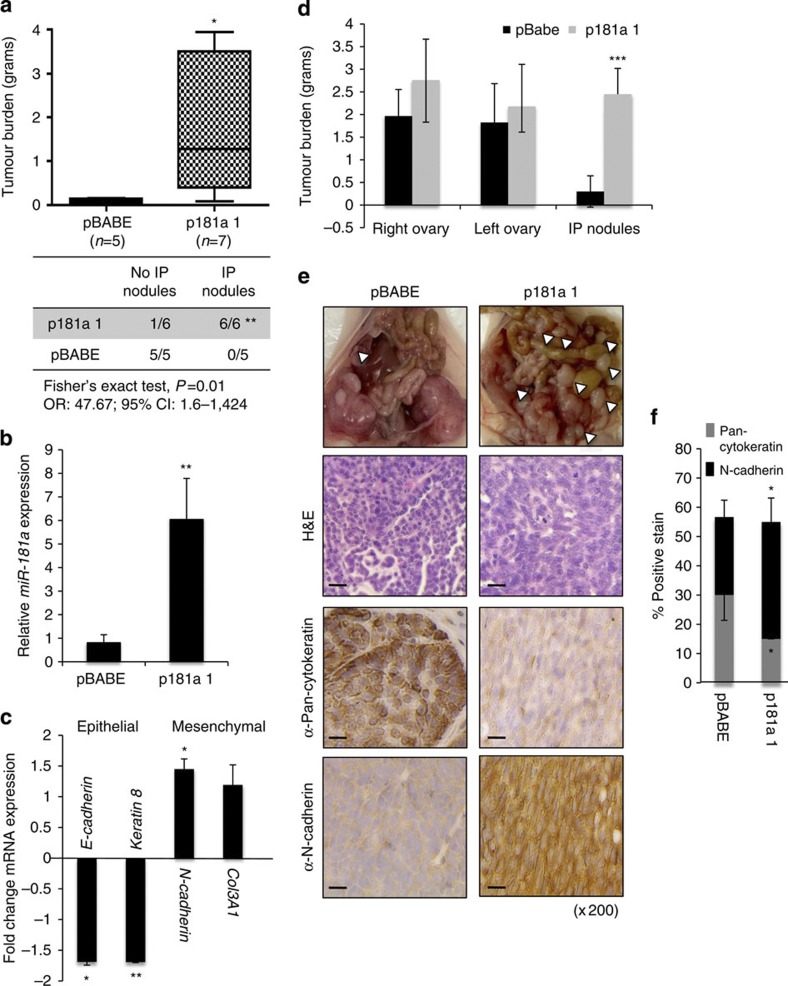

Lastly, we examined the effects of miR-181a on cancer cell dissemination in vivo, using two preclinical orthotopic mouse models of ovarian cancer. First, to assess the ability of miR-181a to promote survival and implantation of ovarian tumours within the peritoneal cavity during late-stage disease, miR-181a-overexpressing or pBABE cells were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) into nude mice. After 3 weeks, tumour cell dissemination and overall tumour burden was measured on necropsy. Interestingly, although the cell lines were injected i.p., all mice formed tumours within the ovary but, remarkably, only the miR-181a-overexpressing cells formed disseminated nodules within the peritoneal cavity (P=0.01, OR: 47.67, 95% CI: 1.6–1424, Fisher’s exact test), which correlated with increased overall tumour burden (P=0.03, Fisher’s exact test; Fig. 3a). On average, each mouse injected with p181a 1-expressing cells had >10 intraperitoneal nodules disseminated throughout the omentum and peritoneum, and some had metastasized to the diaphragm. We confirmed that transcriptional changes in EMT markers were maintained in the miR-181a-expressing cells in vivo through qRT–PCR of epithelial and mesenchymal markers (Fig. 3b,c).

Figure 3. miR-181a regulates EMT and increases tumour burden and incidence of metastasis in vivo.

(a) Total tumour burden (g) in pBABE (n=5) versus p181a-injected mice (n=7) at 3 weeks post i.p. injection (2 × 106 cells; top). Fisher’s exact test correlating the incidence of intraperitoneal nodules with miR-181a expression (bottom); **P=0.01, OR: 46.76, 95% CI: 1.6–1424. (b) Confirmation of miR-181a expression in pBABE (n=5) versus p181a (n=7) cells isolated from harvested tissues as determined by qRT–PCR. Student’s t-test, **P≤0.01. Error bars, s.d. (c) Fold change of epithelial and mesenchymal marker expression as determined by qRT–PCR in miR-181a- (n=7) versus pBABE-injected (n=5) tumour cells. Student’s t-test, *P≤0.05 and **P≤0.01. Error bars, s.d. (d) Quantification of primary ovarian and intraperitoneal tumour burden in mice 3 weeks after intrabursal injection of both pBABE (n=5) versus p181a (n=5) tumour cells (1 × 106 cells). Student’s t-test, ***P≤0.001. Error bars, s.d (e) Gross images of metastatic nodules (top; white arrows). Ovarian tumours have been removed from the p181a 1 mouse to observe the extensive dissemination of tumour nodules throughout the abdomen. Haematoxylin and eosin and IHC staining(s) for pan-cytokeratin and N-cadherin in representative pBABE and p181a 1 tumours. Original magnification, × 200, scale bars, 20 μM (black). (f) Quantification by immunoscoring as shown by percentage of positive staining for pan-cytokeratin and N-cadherin in pBABE (n=5) and p181a 1 (n=5) intraperitoneal tumours. Student’s t-test, *P≤0.05. Error bars, s.d.

Next, to assess the effect of miR-181a on the early events of metastasis, we utilized an orthotopic ovarian xenograft model wherein the pBABE or the p181a-expressing cells were directly injected under the ovarian bursa. Similar to the intraperitoneal model, mice injected with miR-181a-expressing cells had a greater degree of metastatic dissemination compared with the pBABE control (Fig. 3d,e and Supplementary Table S3). Specifically, miR-181a-expressing cells had increased invasion through the ovarian bursa followed by peritoneal spread with colonization to organs within the peritoneal cavity. Significantly larger peritoneal nodules and a higher percentage of nodules that disseminated to the surface of the peritoneum, bowel mesentery, omentum, spleen, and diaphragm were observed in the mice injected with miR-181a-expressing cells (Fig. 3d–f). Interestingly, there were no observed differences in the primary ovarian tumour burden between pBABE- and p181a-injected mice, highlighting that miR-181a affects the invasive capacity of the cells rather than the proliferative state. In addition, immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of the intraperitoneal nodules revealed that the miR-181a tumours had spindle-like, mesenchymal features, whereas the pBABE tumours had a more uniform cuboidal, epithelial growth pattern (Fig. 3f). To definitively quantify these differences in morphology, the per cent of pan-cytokeratin and N-cadherin staining was determined for all tumours, and consistent with the morphological differences the miR-181a-expressing tumours had significantly less pan-cytokeratin (P=0.04, two-tailed Student’s t-test) and more N-cadherin staining (P=0.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test; Fig. 3f).

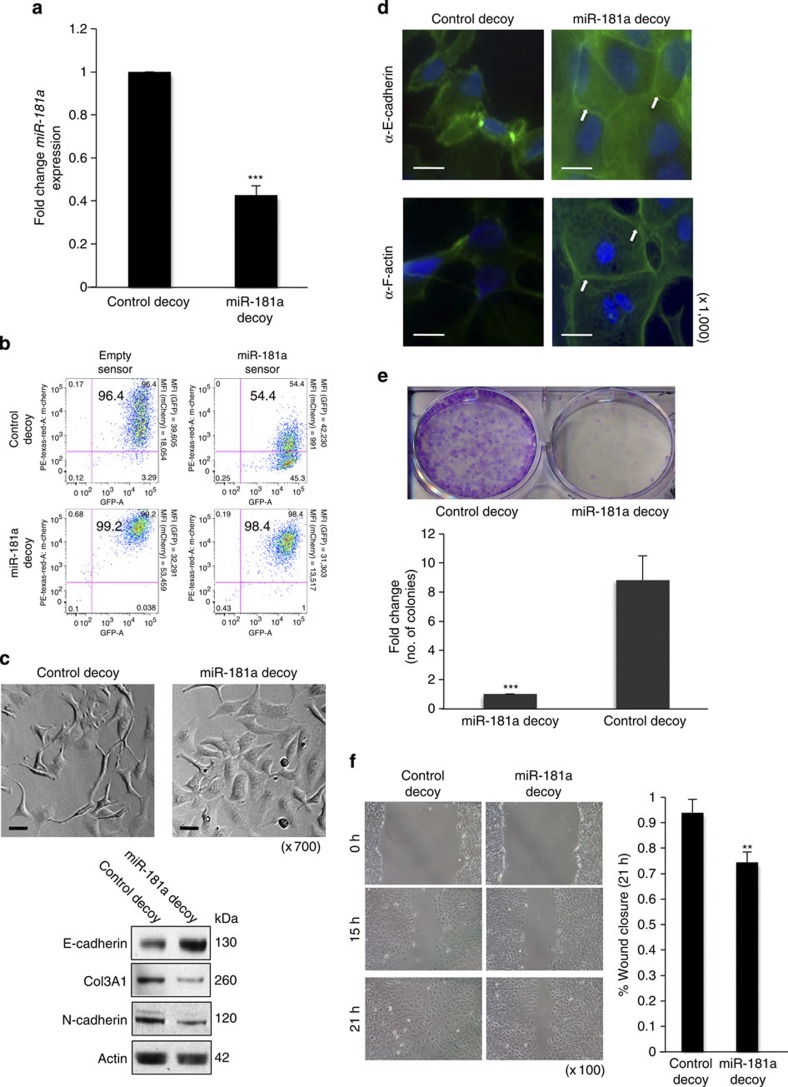

miR-181a inhibition suppresses migration and cell survival

A tough decoy (TuD) vector specific to miR-181a was utilized to determine the effect of miR-181a inhibition on EMT-driven phenotypes20,21. The SKOV3 ovarian cancer line, which has relatively high expression levels of miR-181a, was stably transduced with either the TuD–miR-181a (miR-181a decoy) or TuD–miR-331.3p (control decoy) vector. Cells transduced with TuD–miR-181a exhibited decreased expression levels of miR-181a when compared with cells transduced with TuD–miR-331.3p (Fig. 4a). In addition, the mCherry miR-181a sensor reporter vector confirmed a >80% inhibition of miR-181a function (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4. Stable inhibition of miR-181a results in reduced cellular motility and survival.

(a) Fold change of miR-181a expression levels in SKOV3 cell line stably transduced with miR-181a TuD vector and a control decoy vector as assessed by qRT–PCR. Student’s t-test, ***P≤0.001 (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (b) Monitoring functional activity of miR-181a in SKOV3 miR-181a decoy transduced cells utilizing sensor vectors as measured via mean fluorescent intensity measurements using flow cytometry. (c) Morphological changes (top panels; original magnification, × 700, scale bars, 10 μM (black)) upon functional inhibition of miR-181a. Western blotting (bottom) for epithelial (E-cadherin) and mesenchymal markers (Col3A1 and N-cadherin) to confirm mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition. (d) Effects of miR-181a decoy on E-cadherin and F-actin organization (both shown in green (FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate); blue (DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole)) for nuclear staining). Original magnification, × 1,000, scale bars, 5 μM (white). (e) Clonogenic assay (top) to assess cellular survival in miR-181a decoy cells shown as fold change in number of colonies in control versus miR-181a decoy cells (bottom). Colonies are shown in purple post staining with crystal violet. Student’s t-test, ***P≤0.001 are shown (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (f) Wound-healing assay (left) to evaluate cell motility in miR-181a decoy cells as quantified by per cent wound closure over time points shown (right). Original magnification, × 100, scale bars, 20 μM (black). Student’s t-test, **P≤0.01 (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (all results are shown for SKOV3 cells).

Stable inhibition of miR-181a led to differences in morphology and gene expression consistent with mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition, wherein the cells reverted from a more spindle-like morphology to an epithelial-like phenotype (Fig. 4c). Western blot analysis confirmed a significant increase in the epithelial marker (E-cadherin) and a decrease in mesenchymal markers (N-cadherin and Col3A1; Fig. 4c). In addition, immunofluorescence staining for E-cadherin and F-actin corroborated that targeted inhibition of miR-181a resulted in cells losing their mesenchymal characteristics and becoming more epithelial as indicated by localization of E-cadherin and F-actin at cell–cell junctions (Fig. 4d). Functionally, miR-181a inhibition led to a decrease in cellular survival (Fig. 4e) and rendered the cells less migratory (Fig. 4f).

miR-181a is a novel modulator of the TGF-β signalling pathway

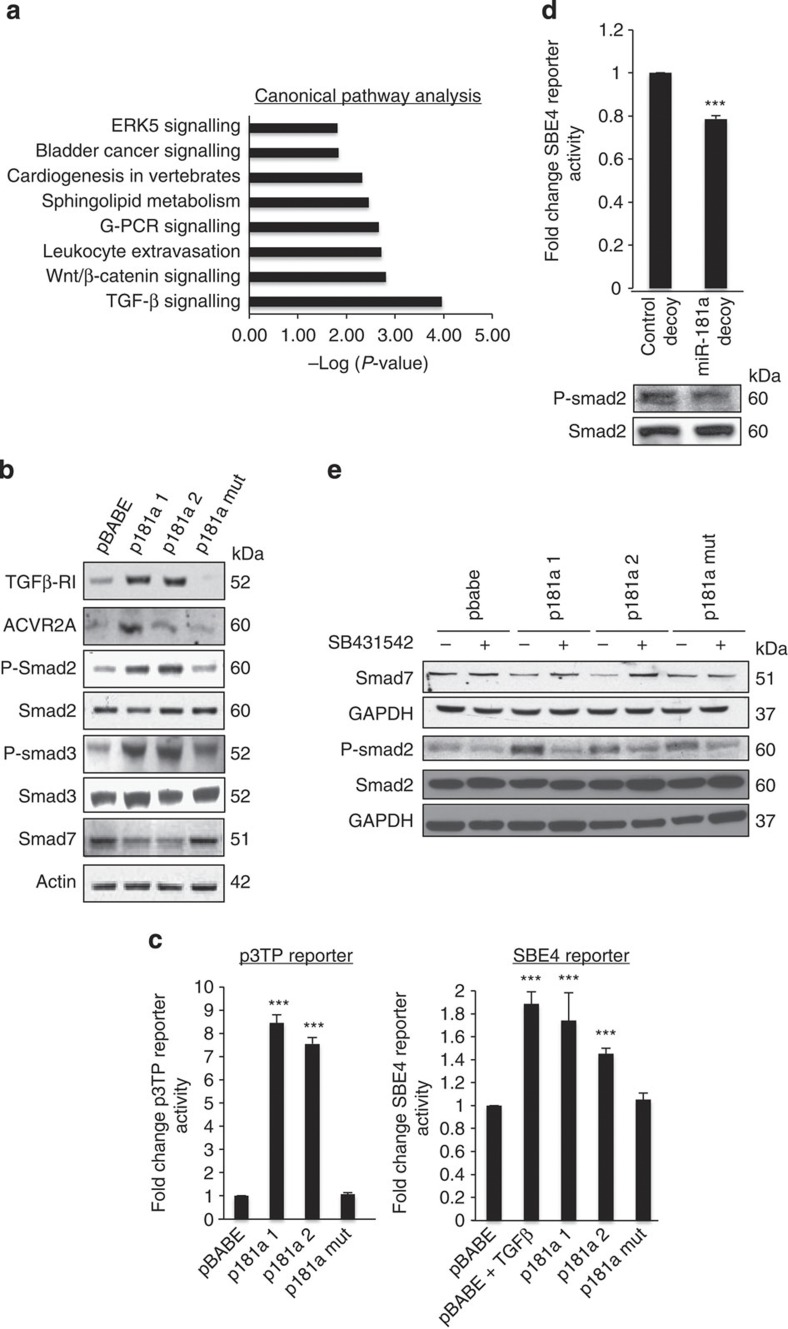

To identify the cellular pathways modulated by miR-181a and define specific targets driving the observed EMT phenotype, we performed high-throughput RNA sequencing (Illumina) on A2780 pBABE and p181a cell lines with a combination of computational target prediction, global transcriptome- and pathway-based analysis. Using a threshold of a minimum fold change >5 or fold change <5 (P<0.05, Fisher exact test,) we identified a total of 739 differentially expressed genes: 705 downregulated and 34 upregulated (Supplementary Data 1 and 2). The high-throughput mRNA sequencing data revealed alterations in the epithelial and mesenchymal markers consistent with global activation of an EMT-like genetic programme (Supplementary Table S4). Interestingly, nearly 7% of the significantly downregulated genes had putative miR-181a-binding site(s) as predicted by TargetScan (Supplementary Table S5). We next utilized the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (Ingenuity, Inc.) to further define potential targets and the major pathways/networks driving the miR-181a-mediated EMT phenotypes. The TGF-β signalling pathway was the most significantly dysregulated pathway among those with significant number of genes altered by >5-fold (P=1.1 × 10−4, Fisher’s exact test) (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5. miR-181a is a novel modulator of the TGF-β signalling pathway in EOC.

(a) Global canonical pathway analysis. RNA-sequencing data sets from A2780 pBABE and p181a 1 cell lines were analysed using the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis software. Statistical significance is expressed as a P-value calculated using the right-tailed Fisher’s exact test. (b) Western blotting for the TGF-β receptor, activin receptor and Smad proteins assessing TGF-β pathway activity in miR-181a-overexpressing and control A2780 cells. (c) TGF-β transcriptional activity was assessed using both the firefly luciferase-based p3TP (left) and SBE4 (right) reporter constructs. Student’s t-test, ***P≤0.001 (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (d) SBE4 reporter activity (top) and phosphorylated Smad2 (P-Smad2) protein expression (bottom), as show by western blotting, in SKOV3 cells transduced with miR-181a decoy compared with the control decoy. Student’s t-test, ***P≤0.001 (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (e) Type-I TGF-β receptor (TGF-β RI) inhibitor, SB431542, effects on miR-181a-mediated activation of TGF-β signalling as measured by P-Smad2 protein expression and suppression of Smad7 protein expression as shown by western blotting.

TGF-β is among several growth factors that can act as inducers of EMT and has been found to play an important role in cancer invasion and metastasis22,23,24. Thus, we sought to explore the role of miR-181a in the regulation of TGF-β signalling in ovarian cancer. Given that the receptor-regulated SMADs (R-Smads), Smad2 and Smad3, are key intracellular mediators of cellular responses to TGF-β signalling, we assessed the effects of miR-181a expression on the phosphorylation of Smad2 (P-Smad2) and Smad3 (P-Smad3). In both stable cell lines expressing miR-181a, P-Smad2 and P-Smad3 expressions were increased with a concomitant decrease in the inhibitory Smad, Smad7 (Fig. 5b). Consistent with the activation of the TGF-β signalling pathway, the activin receptor (ACVR2A) and the type-I TGF-β receptor were also increased in miR-181a-expressing cells (Fig. 5b). Next, we utilized both a TGF-β/activin-responsive p3TP reporter and the SBE4-luc reporter to assess TGF-β transcriptional response25. We found that miR-181a overexpression induced both p3TP and SBE4-luc reporter activities and, conversely, stable inhibition of miR-181a led to a decrease in SBE4-luc reporter expression by >20% and reduction of the phosphorylation of Smad2 (Fig. 5c,d). Furthermore, the addition of a type-I TGF-β receptor kinase inhibitor, SB431542, blocked miR-181a-induced phosphorylation of Smad2 and restored Smad7 expression in the miR-181a-expressing cells (Fig. 5e).

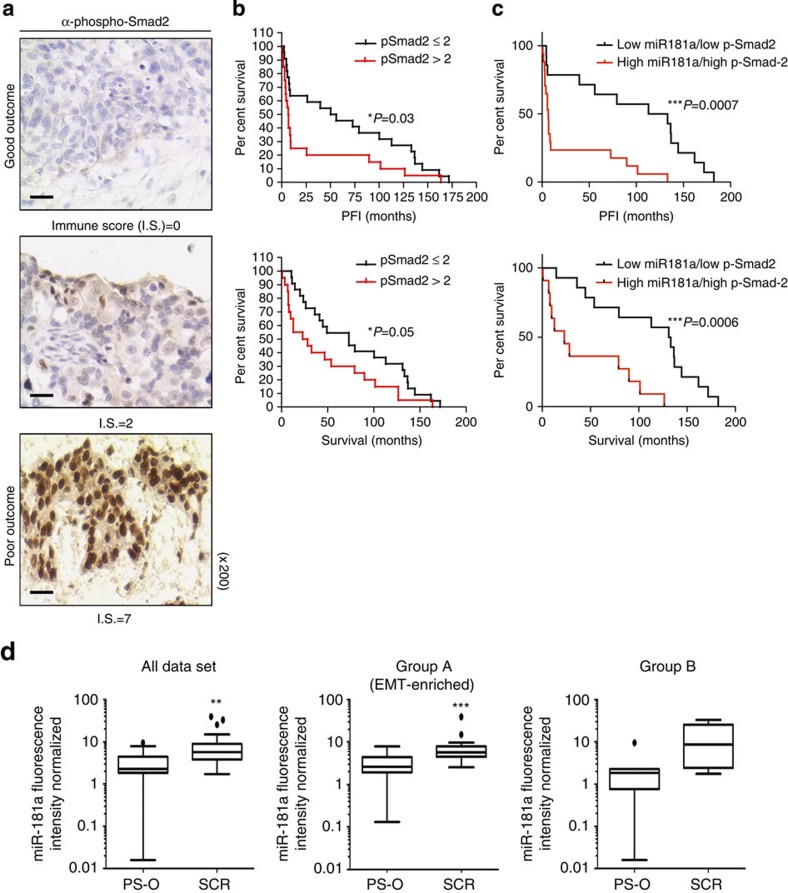

TGF-β activation correlates with poor patient outcome

Given that our data support a role for miR-181a in regulating TGF-β signalling in ovarian cancer and recent studies have shown that a TGF-β gene signature correlates with poor patient outcome26,27,28, we next sought to assess whether TGF-β activation and miR-181a expression correlate with EOC disease progression and recurrence in patient samples. Unlike previous studies, which relied on gene expression analysis to assess TGF-β activation, we utilized a protein-based functional target, P-Smad2, which is phosphorylated on activation of the TGF-β pathway. The distribution of P-Smad2-positive cells, as well as the intensity of staining, varied depending on progression-free interval (PFI) and were mainly localized to the nuclei of tumour cells (Fig. 6a). Overall immune scores in our patient cohort, which were calculated using the Allred scoring system27, ranged from 0 to 7 with an overall median score of 2. There was a significant enrichment of P-Smad2 in tumours from patients with shorter time to recurrence (PFI<6 months; P=0.016, Fisher’s exact test, Supplementary Table S6). Furthermore, higher levels of P-Smad2 significantly correlated with shorter median PFI and survival (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Table S7; PFI: P-Smad2 low versus P-Smad2 high: 55.9 versus 6.3, P=0.01, OR: 8.9, 95% CI: 8.3–9.4; survival: P-Smad2 low versus P-Smad2 high: 79.0 versus 12.6, P=0.007, OR: 6.3, 95% CI: 5.7–6.8, log-rank Mantel–Cox test).

Figure 6. miR-181a is upregulated in recurrent ovarian tumours and TGF-β activation correlates with poor patient outcome.

(a) IHC assessment of nuclear P-Smad2 expression in advanced EOC patients. Immune scores were established using the Allred scoring system (range 0–7). Original magnification, × 200, scale bars, 20 μM (black). (b) Kaplan–Meier curves derived from dichotomizing P-Smad2 expression at the median based on the immune scores show significant differences in PFS and OS. Differences in the PFS (top; P=0.03, OR: 7.9, 95% CI: 7.4–8.5) and median OS (bottom; P=0.05, OR: 2.9, 95% CI: 2.3–3.4; log-rank Mantel–Cox test) are shown. (c) Progression-free interval and OS outcomes in concomitant miR-181a and P-Smad2 expressions. Statistical significance was assessed for differences in PFI (P=0.0007) and PFS (P=0.0006; log-rank Mantel–Cox test) in patient samples with concomitant decrease versus increase in miR-181a and P-Smad2 expression (compared with the expression of each biomarker alone). (d) Box-plot diagrams showing the expression analysis of miR-181a in a clinical cohort of patient matched-tumour specimens from PS-O, primary surgery, ovary (naive to chemotherapy) and SCR, secondary surgery (after tumour has recurred and after two lines of chemotherapy). Left panel shows miR-181a expression in overall cohort collectively (P=0.0024, Wilcoxon signed-rank test); middle panel includes group A tumours, which have a TGF-β-mediated EMT-enriched gene signature (P=0.0006, Wilcoxon signed-rank test), and the right panel includes group B, which do not have an EMT gene signature. Within each box, the horizontal line indicates the median. The top edge of the boxes represents the 75th percentile and the bottom edge represents the 25th percentile (note the log scale on the ordinate). The range is shown as a vertical line ending above and below the 75th and 25th percentile values, respectively. Individual dots represent the outliers. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

In addition, Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed that a concomitant decrease in both miR-181a and P-Smad2 expression resulted in a significantly prolonged PFI (P=0.0007, log-rank Mantel–Cox test; Supplementary Table S7) and OS (P=0.0006, log-rank Mantel–Cox test) compared with the expression of each biomarker alone (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Table S7). Specifically, patient tumours that either had low miR-181a or low P-Smad2 expression had median PFI’s of 56 and 53 months, respectively, whereas in patient tumours with both low miR-181a and P-Smad2 expressions the median PFI doubled to 123 months (P=0.0007, OR: 18.7, 95% CI: 9.2–37.8, log-rank Mantel–Cox test; Fig. 6c and Supplementary Table S7); differences for OS were similar. Patient tumours expressing either low miR-181a or low P-Smad2 had median survival of 66.6 and 72.8 months, respectively, compared with patient tumours that had both low miR-181a and P-Smad2 expressions, in which the median survival doubled to 132.2 months (***P=0.0006, OR: 5.8, 95% CI: 2.6–12.8, log-rank Mantel–Cox test; Fig. 6c and Supplementary Table S7).

A major contributor to the overall poor survival of patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer is tumour recurrence, wherein 70–80% of patients will recur even after complete response to first-line chemotherapy. Given the clinical and functional relevance of miR-181a we have uncovered in our initial patient cohort, we next wanted to assess whether miR-181a was differentially expressed in recurrent tumours compared with matched-primary tumours. The expression of miR-181a was assessed in patient matched-tumour biopsies that were taken at primary surgery (PS-O, chemotherapy-naive ovarian tumour) and at secondary surgery (SCR, after tumour has recurred after at least two lines of chemotherapy). In the SCR tumours, miR-181a expression was upregulated 2.51-fold compared with that in PS-O (P=0.0006, Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Fig. 6d and Supplementary Table S8). In addition, hierarchical bootstrap clustering on the differentially expressed genes and analysis of altered biological networks in this cohort previously revealed that a subset of SCR tumours (group A) had a molecular signature indicative of an EMT phenotype driven by TGF-β pathway activation28; thus, this was an ideal cohort to assess whether miR-181a expression was enriched in recurrent tumours specifically with a TGF-β-induced EMT signature. In accordance with all previous data, we observed that the SCR tumours with distinct molecular features of TGF-β-activated EMT (group A) had elevated miR-181a expression (P=0.0006, Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Fig. 6d and Supplementary Table S8). In recurrent tumours lacking a distinct EMT signature (group B), miR-181a was also upregulated but not as significantly as those with the EMT signature (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Table S8). In addition, in the tumours with an EMT signature, there was a significant correlation between the expression of miR-181a and several EMT markers. Notably, the mesenchymal markers, Col5A1 and Col3A1, drew a positive correlation (Col5A1: R=0.42, P<0.047 and Col3A1: R=0.45, P<0.033, Pearson’s correlation; Supplementary Fig. S7) and the epithelial marker, E-cadherin, had a significant inverse correlation with miR-181a expression (E-cadherin: R=−0.44, P<0.03, Pearson’s correlation; Supplementary Fig. S7).

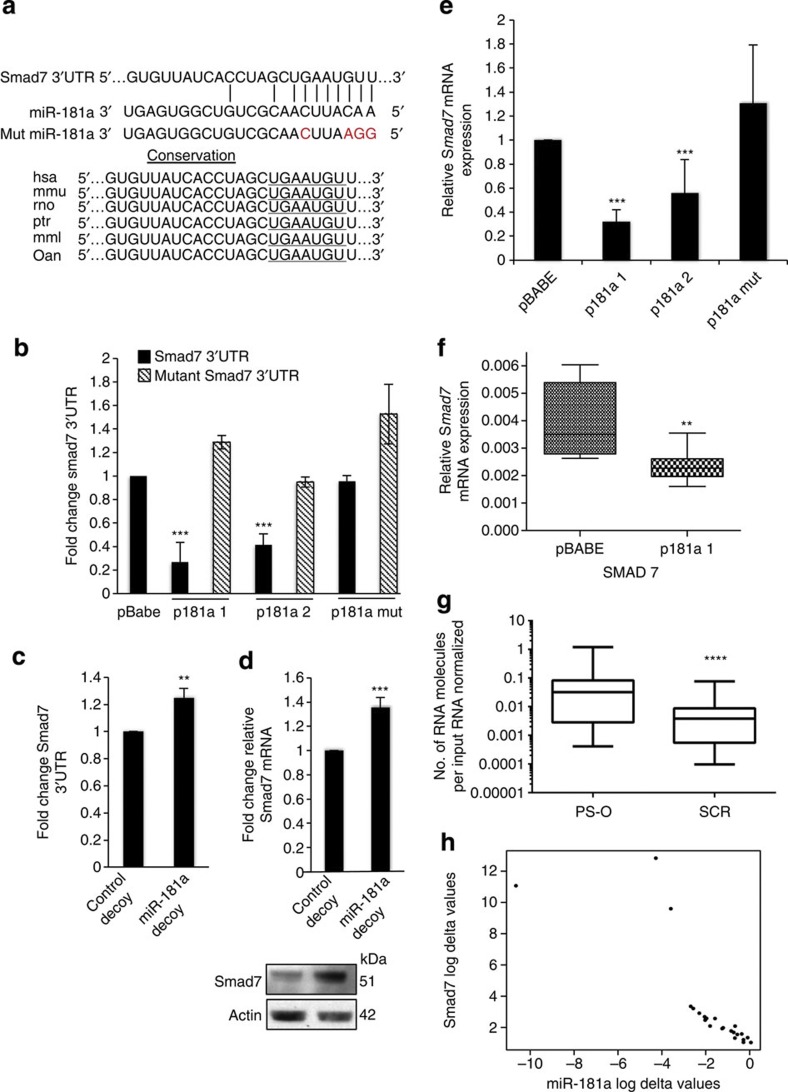

Smad7 is a direct functional target of miR-181a

We next sought to identify the functional target(s) driving miR-181a-mediated TGF-β pathway activation. The expression of Smad7, a key negative regulator of TGF-β signalling, was decreased ~30-fold in miR-181a-expressing cells (Table 1). In addition, correlation analysis using miRConnect revealed that Smad7 expression was significantly negatively correlated with miR-181a levels (summed Pearson’s correlation coefficient=−6.2, Table 1).

Table 1. Predicted miR-181a target genes in the TGF-β pathway.

| Gene ID | Symbol | Fold change | sPCC* |

|---|---|---|---|

| NM_005904 | SMAD7 | −30.9 | −6.2 |

| NM_001106 | ACVR2B | −8.9 | 14.8 |

| NM_001616 | ACVR2A | −7.1 | −4.9 |

| NM_001204 | BMPR2 | −2.6 | −7.9 |

| NM_001130916 | TGFBR1 | +2.1 | −2.5 |

sPCC, summed Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

*sPCC determined by miRConnect analysis (miRConnect.org).

To verify that Smad7, whose miR-181a seed target region is highly conserved among species, is a direct target of miR-181a, a luciferase-based reporter assay containing the Smad7 3′UTR was performed (Fig. 7a,b). Enhanced expression of miR-181a significantly decreased luciferase reporter activity, whereas no change in luciferase expression was evident in the p181a mut cells as compared with the pBABE control cells (Fig. 7b). In addition, a mutated Smad7 3′UTR, in which four nucleotides of the miR-181a binding site is abolished, no longer responds to miR-181a modulation (Fig. 7b). Conversely, sequestration of miR-181a by the aforementioned decoy vectors abrogated the inhibitory effect of the miRNA on the Smad7 3′UTR reporter constructs and led to an increase in both Smad7 mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 7c,d). Consistent with Smad7 3′UTR reporter results, endogenous levels of Smad7 were also significantly downregulated at both the RNA and protein levels in cells stably expressing miR-181a compared with pBABE or p181a mut cells (Figs 5b and 7e); this downregulation was also observed in our in vivo intraperitoneal tumour tissue (Fig. 7f).

Figure 7. Smad7 is a novel functional target of miR-181a.

(a) Conservation of the miR-181a-targeting sites in the Smad7 3′UTR and the miR-181a mutant sequence that abrogates miR-181a binding to target mRNA. (b) Analysis of miR-181a modulation on wild-type or mutant Smad7 3′UTR luciferase reporter plasmid. Student’s t-test, ***P≤0.001 (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (c) Endogenous Smad7 mRNA expression as assessed by qRT–PCR in miR-181a-overexpressing and control A2780 cells. Student’s t-test, ***P≤0.001 (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (d) Smad7 3′UTR luciferase activity in SKOV3 cell lines with stable miR-181a inhibition. Student’s t-test, **P≤0.01 (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (e) Endogenous Smad7 mRNA expression as assessed by qRT–PCR in miR-181a knockdown and control decoy SKOV3 cells. Student’s t-test, ***P≤0.001 are shown (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (f) Relative Smad7 mRNA expression in tumour tissue extracted from athymic mice 3 weeks post i.p. injection of miR-181a or pBABE control cells (Box and Whiskers plot: min to max; **P<0.008, two-tailed Student t-test). (g) Smad7 mRNA expression in matched-primary (PS-O) versus recurrent (SCR) tumours. Wilcoxon signed-rank test, ****P<0.00001. (h) Correlation (r=−0.96, ****P<0.0001, Pearson’s correlation) between miR-181a and Smad7 expression in the matched-primary and recurrent ovarian tumours.

To determine the in vivo relevance of the miR-181a–Smad7–TGF-β axis, we next assessed the expression of Smad7 in primary ovarian tumours. First, we found that Smad7 was significantly downregulated in recurrent ovarian tumours compared with matched-primary tumours (P<0.00001, Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Fig. 7g). Second, analysis of the matched-primary and recurrent ovarian tumours revealed a significant negative correlation between miR-181a and Smad7 expression, consistent with the notion that miR-181a regulates Smad7 expression (r=−0.96, P<0.0001, Pearson’s correlation; Fig. 7h). In addition, given that our data supports the direct regulation of Smad7 by miR-181a and miR-181a correlates with poor patient outcome, it is important to assess whether there were a correlation between Smad7 expression and patient outcome. Smad7 qRT–PCR was performed on all ovarian tumours and a significant correlation between low Smad7 expression and poor patient outcome was observed (Supplementary Fig. S8). Specifically, the median PFI for patients with tumours that had low Smad7 expression was 8.7 months compared with 29.6 months for patients that were expressing higher levels of Smad7 (P=0.05, OR: 3.4, 95% CI: 2.9–3.9, log-rank Mantel–Cox test; Supplementary Fig. S8). In addition, OS also significantly varied between the two groups, wherein patients with low expression of Smad7 in their tumours had a median survival of 36.8 months compared with 76.2 months for those who had high expression (P=0.05, OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.5–2.6, log-rank Mantel–Cox test). Together, this data highlight a hitherto unappreciated role of Smad7 in ovarian cancer and define a unique mechanism by which the TGF-β pathway is activated in ovarian cancer tumours and contributes to poor patient outcome.

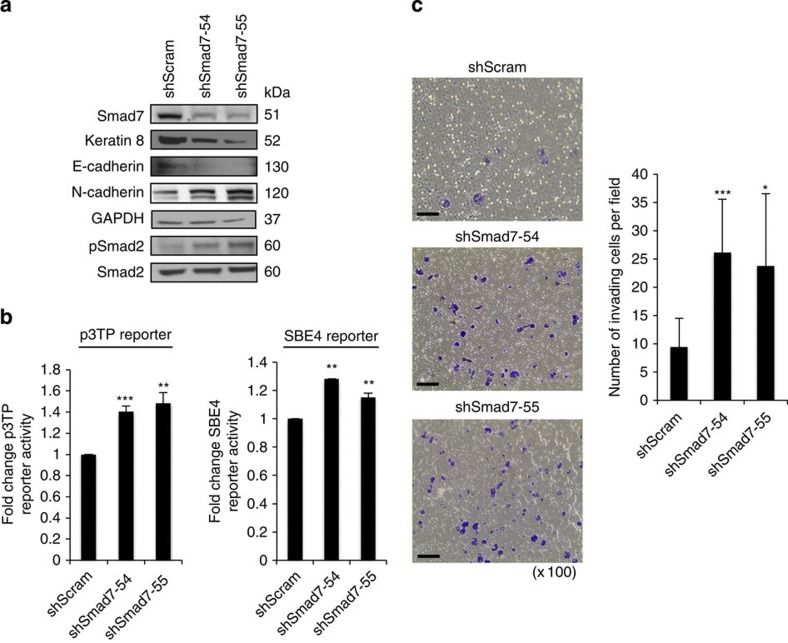

Next, to determine whether Smad7 inhibition can phenocopy the effects of miR-181a overexpression on ovarian cancer cells, we generated two independent cell lines expressing short hairpin RNA targeting different sites of the Smad7 gene (shSmad7-54 and shSmad7-55). Our data reveals that targeted knockdown of Smad7 results in EMT-like features in which there is a decrease of epithelial markers E-cadherin and keratin 8, and an increase in the mesenchymal marker N-cadherin (Fig. 8a). Although we see these changes in EMT marker expression, there are no marked phenotypic changes as observed with miR-181a overexpression, thus suggesting that possibly there are other pathways and genes contributing to the miR-181a-induced EMT phenotype. In addition, we observe that Smad7 inhibition can activate TGF-β signalling as indicated by the induction of phosphorylated Smad2 and a concomitant increase in p3TP and SBE4-luc reporter activities (Fig. 8a,b). Consistent with the induction of EMT-like features and activation of the TGF-β signalling pathway, Smad7 inhibition leads to a marked increase in the invasive potential of ovarian cancer cells (Fig. 8c).

Figure 8. Stable inhibition of Smad7 mimics miR-181a-mediated events.

(a) Epithelial and mesenchymal marker expression in shScram (control) and two shSmad7 (-54 and -55) stable cell lines expressing different short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences. (b) p3TP (left) and SBE4-luc (right) reporter activities in the shScram, shSmad7-54 and shSmad7-55 cells. Student’s t-test, **P≤0.01 and ***P≤0.001 are shown (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (c) Analysis of invasive potential of the shScram, shSmad7-54 and -55 cell lines by a transwell invasion assay (left) and the quantification of invading cell counts per field (right). Original magnification, × 100, scale bars, 100 μM (black). Student’s t-test, *P≤0.05 and ***P≤0.001 (n=3). Error bars, s.d.

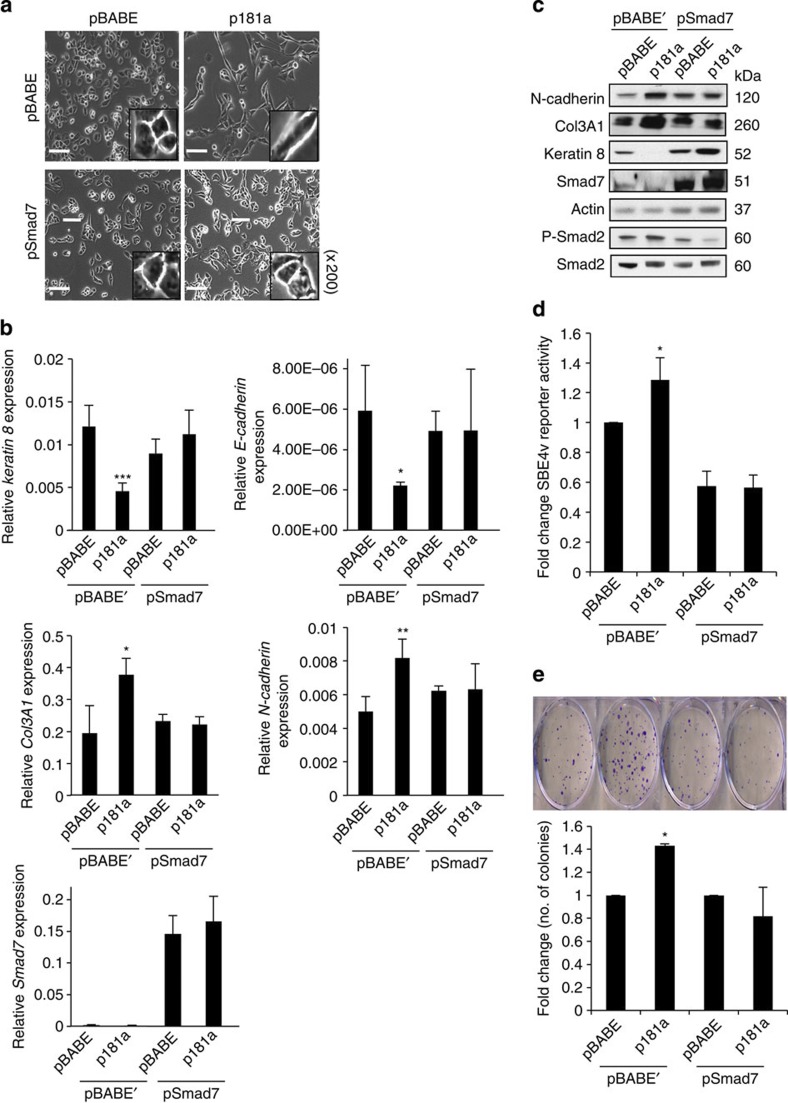

Lastly, to further assess whether Smad7 is a functional target of miR-181a that is mediating the EMT phenotypes, experiments were performed wherein Smad7 lacking the 3′UTR was re-expressed in the pBABE and p181a 1 cells. Smad7 re-expression, which was confirmed to be localized to the cytoplasm (Supplementary Fig. S9), was able to attenuate miR-181a-induced EMT as demonstrated by morphological changes and the relative expression of epithelial and mesenchymal cellular markers E-cadherin, keratin 8, N-cadherin and Col3A1 on both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 9a–c). Re-expression of Smad7 also abrogated the ability of miR-181a to activate TGF-β signalling as shown by SBE4-luc activity assay, as well as phosphorylation of Smad2 (Fig. 9d). In addition, the functional effects of miR-181a overexpression on cellular survival were also abolished by the re-expression of Smad7 (Fig. 9e).

Figure 9. Functional validation of Smad7 effects on miR-181a-mediated EMT phenotypes.

(a) Phase-contrast microscopy images of A2780 cells overexpressing miR-181a or pBABE (control) in the presence and absence of Smad7 (lacking the 3′UTR) reconstitution. Original magnification, × 200, scale bars, 20 μM (white). (b) qRT–PCR analysis showing the relative expression epithelial (top) and mesenchymal marker expression (middle) and Smad7 (bottom) mRNA expression. Student’s t-test, *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01 and ***P≤0.001 (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (c) Epithelial and mesenchymal marker expression in the Smad7 rescue stable cell lines as measured by western blotting. (d) TGF-β signalling pathway activity as measured by SBE4 luciferase activity. Student’s t-test, *P≤0.05 (n=3). Error bars, s.d. (e) Colony-formation assays (top) to assess attenuation of miR-181a-mediated prosurvival phenotype in A2780 cells overexpressing Smad7 and pBABE’ control. Quantification (bottom) is shown as fold change in the number of colonies calculated to pBABE–pBABE or pBABE–pSmad7 controls. Student’s t-test, *P≤0.05 (n=3). Error bars, s.d.

Discussion

The issues of tumour recurrence, drug resistance, enhanced invasion and metastasis remain a challenge in the treatment and the clinical management of EOC. Despite a better understanding of EOC genetic alterations in the recent years, our ability to translate these findings into more effective treatments have been limited by the difficulty in identifying functionally relevant drivers of the disease. Because of the inherent heterogeneity and complex nature of EOC, known common and highly mutated genes, such as in TP53 or BRCA1/2, have not been successfully exploited in the clinical setting. Hence, identifying molecular drivers of EOC will be crucial to a better understanding of its biology and, ultimately, for the development of a therapeutic target in advanced-stage disease.

Herein, we have identified a single miRNA, miR-181a, that can modulate TGF-β signalling to induce and maintain EMT, and affect further downstream events of tumour cell survival, altered response to chemotherapy, migration, invasion and dissemination in vivo. Several studies have demonstrated that TGF-β signalling and EMT contribute to ovarian cancer cell plasticity through the regulation of cellular adhesion to the extracellular matrix, thereby increasing cell motility and invasion, and contribute to poor patient outcome26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. In addition, ovarian tumours and paired ascites fluid secrete significant amounts of TGF-β32,33, thus making it imperative to understand the effects of TGF-β on ovarian tumour biology and the factors that regulate this signalling pathway. In addition, the importance of further understanding the molecular underpinnings involved in TGF-β-induced EMT in EOC was recently highlighted in a comprehensive analysis, which demonstrates that tumours, which display a TGF-β-induced mesenchymal signature, correlate with poor OS. In this study, they also uncovered that a miRNA regulatory network, which consisted of a set of 19 miRNAs that were downregulated and inhibited EMT, governed the ovarian cancer mesenchymal phenotype. However, this study does not explore miRNAs that are upregulated in the more aggressive mesenchymal subtype4. Our present study provides an understanding of how enhanced expression of miR-181a can confer malignant and invasive traits through the modulation of a canonical signalling pathway and a consequent maintenance of a mesenchymal state. Furthermore, inhibition of miR-181a led to a reversion of EMT and subsequent events through decreased TGF-β signalling. Our data confirmed Smad7 as a functional target through which TGF-β-mediated EMT occurs; re-expression of Smad7 lacking its 3′UTR was able to rescue miR-181a-mediated phenotypes, deeming Smad7 as a critical mediator of miR-181a-induced EMT. Other recent studies support the crucial role(s) that miRNAs play in mediating EMT and consequent aggressive disease traits. For example, the miR-106b-25 cluster has also been shown to target Smad7 and mediate TGF-β-induced EMT downstream to Six1 in breast cancer34. miR-9 directly targets E-cadherin and inhibition of miR-9 led to an inhibition of metastasis35. Conversely, the miR-200 and -205 family was shown to target transcriptional repressors of E-cadherin, ZEB1 and SIP1, and re-expression of these miRNAs led to a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition and prevented TGF-β-induced EMT36.

The clinical relevance of EMT in ovarian cancer development and progression is not fully understood, in part, owing to conflicting results with EMT marker gene expression patterns and clinical outcomes. For example, the loss of E-cadherin may correlate with poor survival37,38, but in an additional large-scale study the opposite correlation in high-grade EOC was observed39. Our study suggests that the use of biomarkers that regulate the EMT process, such as miR-181a, P-Smad2 and Smad7, may provide a more functionally relevant prognostic marker(s). In fact, miRNA expression may be a more accurate classifier of tumour origin and stage than mRNA profiling and standard histological procedures40. Consequently, we show that the expressions of miR-181a, Smad7, and P-Smad2, significantly correlate with PFS and OS in a well-annotated advanced-stage EOC patient cohort. Stratifying patients by miR-181a, Smad7, or P-Smad2 expression in their primary tumour before chemotherapy treatment predicted clinical response and survival. Through the use of both an intraperitoneal and intrabursal mouse models of ovarian cancer, we confirmed the functional relevance of miR-181a in ovarian cancer dissemination and progression; we consistently observed that mice implanted with cells expressing miR-181a had increased overall tumour burden with a significantly higher incidence of metastatic nodules in the peritoneum. Importantly, mRNA and IHC analyses of these tumours showed the maintenance of EMT in vivo, as well as decreased levels of Smad7. Furthermore, the analysis of a second clinical cohort of patient matched-primary and recurrent EOC tumours revealed a significant enrichment of miR-181a expression in recurrent tumours compared with primary chemotherapy-naive tumours. This cohort also confirmed the significant association between miR-181a, Smad7, and TGF-β-induced EMT in recurrent tumours with a striking inverse correlation between miR-181a and Smad7 expression. These observations strongly suggest that the pathways that activate miR-181a and in turn leading to Smad7 inhibition are involved in disease progression. Given that enhanced miR-181a expression resulted in the activation of other Smad-dependent protein such as TGF-β R1 and potentially non-canonical TGF-β-related pathways, further studies are warranted to explore the functional and clinical relevance of other miR-181a-regulated pathways in EOC.

Together, this present study highlights a hitherto unappreciated role of miR-181a, Smad7 and the TGF-β signalling pathway in high-grade serous ovarian cancer, and defines a unique mechanism by which the TGF-β pathway is activated in ovarian cancer tumours and contributes to poor patient outcome.

Methods

Analysis of primary human ovarian cancer samples

A de-identified and blinded cohort of 52 primary optimally debulked stage-III papillary serous ovarian cancers with long-term clinical follow-up was provided by Dr Jamal Rahaman (Mount Sinai School of Medicine) from an Ovarian Cancer database established with an institutional human ethics review board approval (02-0783 and 02-0668). Informed consent was obtained from all patients who participated in the study. Total RNA was isolated from duplicate unstained paraffin-embedded sections, provided by Dr Tamara Kalir (Mount Sinai School of Medicine) using the RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit for FFPE (Life Technologies). Real-time PCR analyses for mRNA and miRNA were performed as described in the RNA extraction and real-time PCR section below. The second patient cohort of EOC was selected from a tumour tissue collection of snap-frozen biopsies recruited at the San Gerardo Hospital in Monza (Italy) and routinely stored at −80 °C at the Mario Negri Institute in Milan (Italy). The cohort comprises of 23 stage III–IV patients; tumour (chemotherapy-naive) biopsies were taken at PS-O and at SCR for relapse after several lines of chemotherapy. All clinical and pathological features are described in Supplementary Table S9.

Cell culture

We obtained A2780 cells from Dr Paul Modrich (Duke University), the HEY cells from Dr Gloria Huang (Albert Einstein College of Medicine) and SKOV3 cell lines from the American Type Culture Collection, and cultivated them in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (recommended media). Cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2) at 37 °C. Trypsin (0.25%)/EDTA solution was used to detach the cells from the culture flask for passaging.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For mRNA analysis, complementary DNA was randomly primed from 1 μg of total RNA using the Fermentas cDNA Synthesis kit. Real-time PCR was subsequently performed in triplicate with 1:15 dilution of cDNA using SYBR green PCR system on the 7900HT Fast real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosciences). Data were collected and analysed using SDS 2.3 software (Applied Biosciences). Relative expression levels were determined using the comparative quantification feature of the SDS 2.3 software. All mRNA quantification data were normalized to Actin and 18S. For miRNA analysis, real-time PCR was performed as above using TaqMan microRNA Assay (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using TaqMan probes for hsa-miR-181a, miR-16 and RNU6B (Applied Biosystems). All miRNA data are normalized to a RNU6B and/or miR-16, which display stable expression profile throughout all experiments and patient samples.

18S F: 5′-GGAAAGCAGACATTGACCTCAC-3′ 18S R: 5′-CCATCCTTTACATCCTTCTGTCTGT-3′ Actin F: 5′-GCTTCTCCTTAATGTCACGC-3′ Actin R: 5′-CCCACACTGTGCCCATCTAC-3′ E-cadherin F: 5′-GACCGGTGCAATCTTCAAA-3′ E-cadherin R: 5′ GTCGAGGGAAAAATAGGCTG-3′ NCAD F: 5′–GACGGTTCGCCATCCAGAC-3′ NCAD R: 5′-TCGATTGGTTTGACCACGG-3′ COL3A1 F: 5′-ATATTTGGCATGGTTCTGGC-3′ COL3A1 R: 5′-TGGCTACTTCTCGCTCTGCT-3′ SMAD7 F: 5′-GACACAGTAGAGCCTCCCCA-3′ SMAD7 R: 5′-GAACGAATTATCTGGCCCCT-3′ KRT8 F: 5′-ATGTTGTCCATGTTGCTTCG-3′ KRT8 R: 5′-CCAGGAGAAGGAGCAGATCA-3′ RNU6B: 5′-CGCAAGGATGACACGCAAATTCGTGAAGCGTTCCATATTTTT-3′ miR-16: 5′-UAGCAGCACGUAAAUAUUGGCG-3′ miR-181a: 5′-AACAUUCAACGCUGUCGGUGAGU-3′.

Generation of A2780 stable cell lines

A retroviral construct MDH1-miR-181a-1-PGK-GFP (donated by Dr Chen Z. Cheng, Stanford University) was utilized to generate miR-181a-overexpressing cell lines. Mutations in the miR-181a seed sequence were generated using Change-IT Multiple Mutation Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (USB). Retrovirus was generated by co-transfection of the above constructs with packaging plasmids into Phx cells. Transduced A2780 and HEY were FACS-sorted for green fluorescent protein (GFP) positivity. The FACS data were acquired using the BD LSR II machine and analysed using FlowJo 8.8.7 software.

The pCDNA3.1-Smad7 construct (donated by Dr Carl-Hendrik Heldin, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Sweden), containing Smad7 cDNA lacking the 3′UTR, was excised out of the pCDNA3.1 vector backbone using BamH1 and Xho1 (NEB) and amplified by PCR; the purified cDNA was then ligated into the pBABE-puro vector backbone post digestion with BamH1 and Sal1 (NEB). The newly generated pBABE-puro-Smad7 plasmid was then transfected into Phx cells as described above, and selection of transduced cells was accomplished using 2.5 μg ml−1 puromycin (Invitrogen). For the generation of the shSmad7 stable cell lines, the A2780 cell line was stably transduced with shScrambled and shSmad7 retroviral-based constructs (OriGene) for stable knockdown of Smad7. Retrovirus was generated using the Phx cells and serial infections over 72 h was achieved with polybrene (2 μg ml−1). Positively transduced cells were selected with puromycin (2.5 μg ml−1) and analysed post selection.

miRNA sensor and decoy vectors

A bidirectional lentiviral sensor vector, which expresses GFP and mCherry as two distinct transcripts, was modified to contain four tandem copies of an imperfectly complementary target site for miR-181a to generate a miR-181a sensor vector41. A2780 and SKOV3 cells were virally transduced with the miR-181a sensor and an empty control, and sorted and analysed, as described above. The miRNA decoy vector utilized the TuD configuration18.

Clonogenicity assay

Cell survival was assessed through seeding 250 cells per well in a 6-well plate and were fixed in a 10% acetic acid/10% methanol (in diH2O) solution, and stained with 1% crystal violet (in methanol) after 7 days of growth. Colonies were counted using ImageJ.

Cell migration and invasion assay

For the wound-healing assay, 4 × 105 cells were seeded into 6-well plates and were serum-starved for 24 h at full confluency. A sterile 200 μl pipette tip was used to scratch the cells to form a wound. The cells were washed with PBS and cultured in serum-free medium (and full media for SKOV3 cells). Wound closure was visualized with an inverted Nikon Eclipse TS100 phase-contrast microscope and measured using Nikon NIS-Element Basic Research v3.2 software. For the transwell migration assay (Cell BioLabs), 3 × 105 cells (in serum-free media) were plated into the upper chamber. The cells were incubated in 37 °C for 24 h and migratory cells were subsequently harvested for quantification via a colorimetric absorbance reading at 560 nm.

For the invasion assay, 2.5 × 104 cells were suspended in serum-free medium and seeded into the inserts of a 24-well BD BioCoat Matrigel Invasion Chamber (catalogue number 354480) in triplicate. Inserts were co-cultured in a well of fetal bovine serum-containing media as an attractant. Chambers along with inserts were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 atmosphere for 48 h. Inserts were then removed and the upper surface of the membrane was scrubbed to remove non-migrating cells. Inserts were then fixed with 100% methanol and stained with Millipore Cell Satin (catalogue number 90144). Multiple × 10 images per well were acquired and average counts were calculated.

Gene expression analysis using RNA-sequencing data

Total RNA was extracted from two polyclonal pools of A2780 cells expressing exogenous miR-181a (p181a 1 and p181a 2) and pBABE control cells. The Illumina RNASeq kit was used to prepare sequencing libraries. The method is as follows: 1 μg of high-quality total RNA was incubated with oligo(dT) magnetic beads (SeraMag) to enrich for mRNA with poly-A tails. Eluted RNA was randomly cleaved by incubation at 94 °C with a magnesium buffer. The RNA is ethanol precipitated and then reverse transcribed (Invitrogen SuperScript II). DNA polymerase is added to generate a second strand. Double-stranded DNA after second-strand synthesis contains ends with 5′- and 3′-overhangs, and these are filled in using T4 polymerase and T4 polynucleotide kinase, resulting in a blunt-ended DNA molecule. Then a deoxyadenosine 5′-tail is added to DNA strands using the Klenow fragment (exo-). Double-stranded DNA adapters with 3′-thymidine overhangs are ligated to the deoxyadenosine-tailed library using T4 ligase. The library was then size selected on a 2% agarose gel and amplified with 15 cycles of PCR (NEB Phusion polymerase). This procedure adds the sequences needed for binding to the Illumina flow cell and sequencing primer-binding sites. RNA-Seq libraries were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 for a 100-nt read length. Transcriptome raw reads were mapped to the human reference genome (hg19). The coverage over the length of the gene is variable due to various biases inherent to the sequencing and sample preparation process. To avoid problems arising from this, we generated a density profile using windows of 50 bp sliding over the length of each gene, and the median of this density profile was picked as the representative coverage for the gene using an in-house mRNA-seq expression profile pipeline. The coverage is corrected using log-transformation and quantile normalization. Putative miRNA targets were predicted using TargetScan ( http://www.targetscan.org) and miRConnect ( http://mirconnect.org). RNA-sequencing data has been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus accession code GSE52077.

Smad7 3′UTR reporter assay

Smad7 3′UTR reporter plasmid (500 ng) and pGL3-control (100 ng, for normalization) (Promega) were co-transfected with Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) into cells seeded in 12-well plates (1 × 105 cells per well). Cells were harvested and luciferase activities were analysed after 24 h using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the USB Change-IT Mutagenesis Kit. To mutate four nucleotides within the miR-181a-binding site within the Smad7 3′UTR, we used the following mutagenesis primer sequence: (Phos) 5′-GTGTTATCACCTAGCTCTTAGTTTTTCTAAAGGAGTT-3′.

p3TP- and SBE4-luciferase reporter assays

Cells were seeded at 50,000 per well and were serum-starved 6 h pre-transfection. The p3TP reporter construct (900 ng; AddGene) and tkrl-control construct (150 ng) were co-transfected with Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen); in addition, SBE4-luc (500 ng) and tkrl (100 ng) were utilized in separate experiments. Recombinant TGF-β ligand (eBiosciences) was added 6 h before harvest and luciferase activity was assessed as described above.

Immunoblotting

Whole-cell protein extracts were obtained with radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer following standard protocols. The protein extracts were denatured and 40–50 μg of each sample were separated on 12% SDS–PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk (LabScientific, Inc.) in TBS-Tween buffer, the membranes were probed with antibodies against E-cadherin (1:250, Santa Cruz), N-cadherin (1:250, Santa Cruz), Smad7 (1:200, Santa Cruz), ACTR-IIA (1:500, Santa Cruz), ACTR-IIB (1:500, Santa Cruz), actin (1:1,000, Santa Cruz), keratin 8 (1:250, Epitomics), Col3A1 (1:200, Abcam), Smad2 (1:500, Cell Signaling), P-Smad2 (1:250, Cell Signaling), Smad3 (1:200, Cell Signaling), P-Smad3 (1:100, Cell Signaling) and fibronectin (1:1,000, BD Transduction Lab). Membranes were exposed using enhanced chemiluminescence (Roche) method following manufacturer’s instructions. Full scans of all western blots are included in Supplementary Fig. S10.

IHC staining

Paraffin-embedded ovarian tumour tissue samples were deparaffinized in Histoclear and rehydrated in successive ethanol washes. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched using 10–30% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 min. Antigen retrieval was achieved at 124 °C for 5 min and the tissues were subsequently incubated in normal goat serum (in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. The tissue was incubated in primary anti-P-Smad2 antibody (1:250, Cell Signaling) and Smad7 (1:100, R&D Systems) overnight at 4 °C. Incubation in secondary antibody (goat-derived anti-rabbit IgG) was followed by addition of horseradish peroxidase (Invitrogen). 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (Vectashield) was added for 5 min; counterstaining was achieved in haematoxylin. Subsequently, the tissue were dehydrated in successive ethanol washes and deparaffinized in Histoclear before mounting with Permount. The diluent used for this protocol was 5% BSA in TBS-Tween. Overall immune scores were calculated using the Allred scoring system25. After dichotomizing, the group at that median Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed and log-rank test was utilized to assess the statistical significance. The IHC analyses of mouse samples were as aforementioned using pan-cytokeratin (Invitrogen) and N-cadherin (Abcam).

In vivo studies

All in vivo experiments were performed according to approved protocols from the Animal Research Committee at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and Case Western Reserve University. For the intraperitoneal model, A2780 pBABE and p181a 1 cells (2 × 106) were injected i.p., whereas (1 × 106) of A2780 pBABE and p181a 1 cells were injected under the ovarian bursa in 6- to 8-week-old female nude mice. All mice were killed after 3 weeks and ovarian and intraperitoneal nodules were extracted and weighed to compare relative tumour burden. RNA from tumour tissue was extracted as described above. All tumours were subsequently analysed by haematoxylin and eosin staining and by immunohistological staining for epithelial (pan-cytokeratin) and mesenchymal markers (N-cadherin).

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise noted, data are presented as mean±s.d. from three independent experiments, and Student's t-test (two-tailed) was used to compare two groups (P<0.05 was considered significant) for independent samples.

Author contributions

A.P. and C.L. contributed equally to this manuscript. A.P., C.L., P.J., V.K., F.W. and A.D. designed and performed experiments and analysed data. A.B., G.M. and B.D.B. provided miRNA decoy vectors and helped with the miRNA sensor experiments. H.S. performed the bioinformatics analysis for the high-throughput mRNA-sequencing data. C.R. performed biostatistical analysis for patient studies. S.M. assessed miR-181a and EMT markers in the second independent cohort of EOC patients. R.F., D.F., M.D. and J.R. provided primary patient samples. T.K. and R.W.R. performed the pathological analysis for patient tumour samples. A.D. designed the project. A.P, C.L. and A.D. wrote the manuscript. G.N., S.M. and A.D. contributed to editing the manuscript.

Additional information

Accession codes: The RNA sequencing data have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus under accession code GSE52077.

How to cite this article: Parikh, A. et al. microRNA-181a has a critical role in ovarian cancer progression through the regulation of the epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nat. Commun. 5:2977 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3977 (2014).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S10 and Supplementary Tables S1-S9

Genes that are upregulated = 5-fold in A2780-p181a cells compared to their A2780-pBABE control cells. Genes in the table are labelled by gene name and Refseq #.

Genes that are downregulated = 5-fold in A2780-p181a cells compared to their A2780-pBABE control cells. Genes in the table are labelled by gene name and Refseq #.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Chong for pSBE4-luc vector, Dr Paul Modrich for the A2780 cell lines, Dr Chen Z. Cheng and Dr Carl-Hendrik Heldin for the expression vectors, Dr William Schmeimann for the p3TP vector and Dr Scott Howell for his help with immunofluorescence and microscopy work. RNA sequencing was performed at the Institute for Genomics and Multiscale Biology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine. We thank Vyom Mehta and Omar Jabado for performing the RNA-Seq sample preparation. This work was supported by grants from the Ovarian Cancer Research Program CDMRP (W81XWH-11-1-0609), Department of Defense (A.D.), Ovarian Cancer Research Fund Liz Tilberis Scholar (A.D.) and the Young Scientist Cancer Research Fund at Mount Sinai School of Medicine (A.D. and G.N.). This research was supported by the Athymic Animal and Xenograft Core Facility of the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30CA043703). We thank the Harrington Discovery Institute and the Pardee-Gerstacker Professor in Cancer Research for thier support (G.N.). We acknowledge the generous contributions of the Nerina and Mario Mattioli Foundation, ACTO and the Italian Association for Cancer Research (IG11673). We would also like to acknowledge Norma C. and Albert I. Geller for their support.

References

- Siegel R., Ward E., Brawley O. & Jemal A. Cancer statistics. Cancer J. Clin. 61, 212–216 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman J. D. et al. Borderline ovarian tumors: diverse contemporary viewpoints on terminology and diagnostic criteria with illustrative images. Hum. Pathol. 35, 918–933 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D. et al. Intregrated analyses identify a master microRNA regulatory network for the mesenchymal subtype in serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Cell 23, 186–199 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M. S., Lu J., Mercer K. L., Golub T. R. & Jacks T. Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nat. Genet. 39, 673–677 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateescu B. et al. miR-141 and miR-200a act on ovarian tumorigenesis by controlling oxidative stress response. Nat. Med. 17, 1627–1635 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio M. V. et al. microRNA signatures in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 8699–8707 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam E. J. et al. MicroRNA expression profiles in serous ovarian carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 2690–2695 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N. et al. MicroRNA microarray identifies Let-7i as a novel biomarker anti-therapeutic target in human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 68, 10307–10314 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya N. & Morin P. J. MicroRNAs in ovarian carcinomas. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 17, F77–F89 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya N. et al. MicroRNA expression and identification of putative miRNA targets in ovarian cancer. PLoS One 18, e2436 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell D. et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 474, 609–615 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. et al. MiR-181 mediates cell differentiation by interrupting the Lin28 and let-7 feedback circuit. Cell Death Differ. 19, 378–386 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. C. et al. miR-181 as a putative biomarker for lymph-node metastasis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral. Pathol. Med. 40, 397–404 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J. et al. Identification of microRNA-181 by genome-wide screening as a critical player in EpCAM-positive hepatic cancer stem cells. Hepatology 50, 472–480 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulos D., Jaeger S. A., Hirsch H. A., Bulyk M. L. & Struhl K. STAT3 activation of miR-21 and miR-181b-1 via PTEN and CYLD are part of the epigenetic switch linking inflammation to cancer. Mol. Cell 39, 439–506 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. A., Sossey-Alaoui K., Thompson C. L., Danielpour D. & Schiemann W. B. TGF-β upregulates miR-181a expression to promote breast cancer metastasis. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 150–163 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corson T. W. et al. Kif14 is a candidate oncogene in the 1q minimal region of genomic gain in multiple cancers. Oncogene 24, 4741–4753 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therlault B. L. & Nachtigal N. W. Human ovarian cancer cell morphology, motility, and proliferation are differentially influenced by autocrine TGFβ superfamily signalling. Cancer Lett. 313, 108–121 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navon R. et al. Novel rank-based statistical methods reveal microRNAs with differential expression in multiple cancer types. PLoS One 11, e8003 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi T., Ozaki Y. & Iba H. Vectors expressing efficient RNA decoys achieve long-term suppression of specific microRNA activity in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 6, e43 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccarini A. et al. Kinetic analysis reveals the fate of a microRNA following target regulation in mammalian cells. Curr. Biol. 21, 369–376 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Ingolia N., Weissman J. & Bartel D. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature 466, 835–840 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberg M. & Kalluri R. The role of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in renal fibrosis. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 82, 175–181 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardali K. & Moustakas A. Actions of TGF-beta as tumor suppressor and pro-metastatic factor in human cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1, 21–62 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleman J., Jansen M. P., Burger C., van der Burg M. E. & Berns E. M. Integrated genomics of chemotherapy resistant ovarian cancer: a role for extracellular matrix, TGFbeta and regulating microRNAs. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 25–30 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tothill R. W. Novel molecular subtypes of serous and endometrioid ovarian cancer linked to clinical outcome. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 5198 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allred D. C., Harvey J. M., Berardo M. & Clark G. M. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Mod. Pathol. 11, 155–168 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchini S. et al. Resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy is associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition in epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 49, 520–530 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin R. L., Tran H. & Karlan B. Y. Loss of c-myc repression coincides with ovarian cancer resistance to transforming growth factor beta growth arrest independent of transforming growth factor beta/Smad signaling. Cancer Res. 63, 1413–1419 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura S. et al. The activated transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway in peritoneal metastases is a potential therapeutic target in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 130, 20–28 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do T. V., Kubba L. A., Du H., Sturgis C. D. & Woodruff T. K. Transforming growth factor-beta1, transforming growth factor-beta2, and transforming growth factor-beta3 enhance ovarian cancer metastatic potential by inducing a Smad3-dependent epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Mol. Cancer Res. 6, 695–705 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L. et al. Tissue transglutaminase links TGF-β, epithelial to mesenchymal transition and stem cell phenotype in ovarian cancer. Oncogene 31, 2521–2534 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen R. et al. Expression and prognostic significance of TGF-beta isotypes, latent TGF-beta 1 binding protein, TGF-beta type I and type II receptors, and endoglin in normal ovary and ovarian neoplasms. Lab. Invest. 73, 213–220 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. L. et al. The miR-106b-25 cluster targets Smad7, activates TGF-beta signaling, and induces EMT and tumor initiating cell characteristics downstream of Six1 in human breast cancer. Oncogene 31, 5162–5171 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L. et al. Therapeutic silencing of miR-10b inhibits metastasis in a mouse mammary tumor model. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 341–347 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory P. A. et al. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 593–601 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faleiro-Rodrigues C., Macedo-Pinto I., Pereira D. & Lopes C. S. Prognostic value of E-cadherin immunoexpression in patients with primary ovarian carcinomas. Ann. Oncol. 15, 1535–1542 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darai E. et al. Expression of cadherins in benign, borderline, and malignant ovarian epithelial tumors. Hum. Pathol. 28, 922–928 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrocchi L., Green A. R., Martin S., Durrant L. & Deen S. The cadherin switch in ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma is associated with disease progression. Virchows Arch. 459, 21–29 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J. et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature 435, 834–838 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccarini A. & Brown B. D. Monitoring microRNA activity and validating microRNA targets by reporter-based approaches. Methods Mol. Biol. 667, 215–233 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S10 and Supplementary Tables S1-S9

Genes that are upregulated = 5-fold in A2780-p181a cells compared to their A2780-pBABE control cells. Genes in the table are labelled by gene name and Refseq #.

Genes that are downregulated = 5-fold in A2780-p181a cells compared to their A2780-pBABE control cells. Genes in the table are labelled by gene name and Refseq #.