Abstract

Background

Case reports and smaller case-control studies suggest an association between celiac disease (CD) and urticaria, but risk estimates have varied considerably across studies and as yet there are no studies on CD and the risk of future urticaria.

Objective

To examine the association between CD and urticaria.

Methods

We identified 28,900 patients with biopsy-verified CD (equal to Marsh stage 3) and compared them with 143,397 age- and sex-matched controls with regards to the risk of urticaria and chronic urticaria (duration ≥6 weeks). Hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated using a Cox regression model.

Results

During follow-up, 453 patients with CD and no previous diagnosis of urticaria developed urticaria (expected n=300) and 79 of these 453 had chronic urticaria (expected n=41). The corresponding HRs were 1.51 for any urticaria (95%CI=1.36–1.68) and 1.92 for chronic urticaria (95%CI=1.48–2.48). The absolute risk for urticaria in CD was 140/100,000 person-years (excess risk=47/100,000 person-years). Corresponding figures for chronic urticaria were 24/100,00 person-years and 12/100,000 person-years. Patients with CD were also at increased risk of having both urticaria (odds ratio, OR=1.31; 95%CI=1.12–1.52) and chronic urticaria (OR=1.54; 95%CI=1.08–2.18) prior to the CD diagnosis.

Conclusion

This study suggests that CD is associated with urticaria, especially chronic urticaria.

Keywords: autoimmunity, celiac, coeliac, gluten, inflammation, population-based, skin, urticaria

Introduction

Urticaria is characterized by a rapid onset of wheals, angioedema, or both.[1, 2] The American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology estimates that between 15–24% of people in the United States will experience acute urticaria, angioedema, or both at some point in their lives.[3] Chronic urticaria (duration ≥6 weeks)[1] is seen in about 0.5–1% of the general population.[4, 5] Although this is less common than acute urticaria, chronic urticaria is associated with a substantial decrease in quality of life.[6]

Celiac disease (CD) is an immune-mediated disease occurring in about 1–2% of the Western population.[7] CD is triggered by gluten exposure in genetically sensitive individuals, requiring lifelong treatment with a gluten-free diet (GFD).[8] It has been linked to an excess risk of mortality,[9, 10] malignancy,[11, 12] and other comorbidities, especially autoimmune diseases.[13, 14]

Over the past few years, a number of case reports have indicated a positive association between urticaria and CD,[15–18] but also with other autoimmune diseases[19]. Patients with CD also demonstrate an increased mucosal permeability and hypothetically an increased passage of antigens, and subsequently the formation of immune complex, may contribute to an excess risk of urticaria.[20]

Recent reports link cold urticaria to CD[21] and to autoimmunity.[22] So far, there are only three case-control studies on urticaria and CD[19, 23, 24] (no cohort studies available) and these present discrepant results (Table 1). Explanations for the conflicting results include small sample size (together the two studies involved only five patients with both CD and urticaria),[23, 24] and single-center source populations with patient characteristics that may differ from that of the average patient with chronic urticaria. Additional limitations are the lack of adult patients and that none of the studies examined the relationship between CD and future urticaria. Just recently, Israeli researchers presented data from a health database on chronic urticaria and a number of autoimmune diseases.[19] That case-control study found an almost 27 times increased risk of CD in patients with chronic urticaria but confidence intervals were wide with the 95% upper confidence interval exceeding 100.[19] These data contrast with the prevalence of tissue transglutaminase antibodies in the same patients with chronic urticaria, (0.3% of female patients and 0.1% of male patients) were antibody positive),[19] levels that are actually lower than in most screening studies of the general population in the Western world.[25]

Table 1.

A summary of previous publications on celiac disease in patients with urticaria.

| Study | Cases* | Controls | OR | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With celiac disease, n(%) | ||||

| Caminiti [23] | 4/79 (5.0) | 17/2542 (0.7) | 7.7 | 0.003 |

| Gabrielli 23] | 1/80 (1.2) | 1/264 (0.4) | 3.3# | 0.412# |

| Confino-Cohen [19] | § /12,778 | § / 10,714 | 27.0 | <0.0005 |

SIR, Standardized incidence ratio. OR, Odds ratio. Obs, observed. Exp, Expected

Cases with urticaria. E.g. in the study by Caminiti et al, 4/79 individuals with urticaria (cases) had celiac disease vs. 17/2545 controls (without urticaria).

Calculated by us

No data on the number of cases and controls with celiac disease

The primary objective of this cohort study was therefore to estimate the risk of future urticaria (any or chronic) in a nationwide cohort of more than 28,000 patients with CD.

Methods

We investigated the risk of urticaria and chronic urticaria in patients with biopsy-verified CD. Data on urticaria were obtained from the Swedish Patient Register[26] that contains both inpatient and hospital-based outpatient care. Linkages between biopsy data and urticaria data were made possible through the use of the unique personal identity number (PIN) assigned to each Swedish resident.[27]

Study participants

We contacted all 28 pathology departments in Sweden and asked information technology (IT) personnel to identify all individuals with CD (equal to small intestinal villous atrophy (VA, Marsh stage 3)[28] through computerized biopsy reports. The IT personnel delivered data on PIN, date of biopsy, topography (duodenum or jejunum) and morphology codes in patients with VA. Patients were identified according to pre-specified SnoMed histopathology codes (see appendix). Validation of the current dataset has been described elsewhere.[29]

In addition to VA biopsy report data, we obtained data on individuals with inflammation without VA (Marsh 1–2) and normal small intestinal mucosa (Marsh 0).

In total, we identified 351,403 unique biopsy reports in 287,586 unique individuals (n=29,148 unique individuals with CD and n=13,446 individuals with intestinal inflammation).[29] A regional subset of data on normal biopsy performed at any of 10 university hospitals in Sweden was then matched with positive CD serology of the corresponding biochemistry departments from these hospitals.[30] The purpose of this matching was to identify a group of individuals with normal mucosa but positive CD serology (defined as having an IgA or IgG antigliadin, endomysial or tissue transglutaminase antibodies within 180 days before biopsy and 30 days after biopsy).[30] Patients whose small intestinal biopsy report did not show VA were used as secondary controls to determine whether a potential association between CD and urticaria was specific to those with CD or influenced by having a biopsy independent of its outcome.

The government agency Statistics Sweden then matched each individual undergoing biopsy (including those with CD, those with inflammation and those with normal mucosa but positive CD serology, n=46,330) with up to five reference individuals from the Total Population Register.[31] Matching variables included age at biopsy, sex, county of residence and calendar year. We then excluded 174 individuals in whom the biopsy could potentially have originated from the ileum and not the duodenum/jejunum, as well as another 35 individuals in whom Statistics Sweden had failed to identify an age- and sex-matched reference individual or was unable to link to data on vital status. The remaining dataset was identical to that of our study on mortality (CD: n=29,096; controls: n=144,522)[9]. For our main prospective analysis, we then excluded participants with an urticaria diagnosis prior to biopsy and study entry (CD: n=196; controls: n=714) and another 411 controls since their index individuals with CD had been excluded for the above reasons (all analyses were performed stratum-wise, requiring at least one index individual with CD in each stratum). Numbers and characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study participants.

| Celiac disease | Matched reference individuals | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 28,900 | 143,397 |

| Age at study entry, years (median, range)* | 30,0–95 | 30,0–95 |

| Age 0–19 (%) | 11,733 (40.6) | 58,446 (40.8) |

| Age 20–39 (%) | 5,262 (18.2) | 26,108 (18.2) |

| Age 40–59 (%) | 6,432 (22.3) | 32,023 (22.3) |

| Age ≥60 (%) | 5,473 (18.9) | 26,820 (18.7) |

| Entry year (median, range) | 1998, 1969–2008 | 1998, 1969–2008 |

| Follow-up#, years (median, range) | 10 (0–41) | 10, 0–41 |

| Females (%) | 17,867 (61.8) | 88,750 (61.9) |

| Males (%) | 11,033 (38.2) | 54,647 (38.1) |

| Calendar year | ||

| -1989 | 4,087 (14.1) | 20,267 (14.1) |

| 1990–99 | 12,009 (41.6) | 59,552 (41.5) |

| 2000- | 12,804 (44.3) | 63,578 (44.3) |

| Country of birth, Nordic§ | 27,952 (96.7) | 135,212 (94.3) |

| Type 1 diabetes§ | 946 (3.3) | 591 (0.4) |

| Autoimmune thyroid disease§ | 1,421 (4.9) | 2,477 (1.7) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis § | 320 (1.1) | 927 (0.6) |

| Lupus erythematosus§ | 145 (0.5) | 244 (0.2) |

Ages were rounded to the nearest year.

Follow-up time until diagnosis of urticaria, death, emigration, or December 31, 2009, whichever occurred first. In reference individuals follow-up can also end at the time of small intestinal biopsy.

p<0.001.

Definition

We defined urticaria as having a relevant ICD code in the Swedish Patient Register (ICD-7: 243; ICD-8: 708; ICD-9: 708; ICD-10: L50). Chronic urticaria was defined as having at least two admissions or physician visits for any of these codes with at least 6 weeks in between admissions/visits.

The Swedish Patient Register began in 1964 and became nationwide in 1987.[26] Hospital-based outpatient data were added from 2001.

Statistical Methods and Analyses

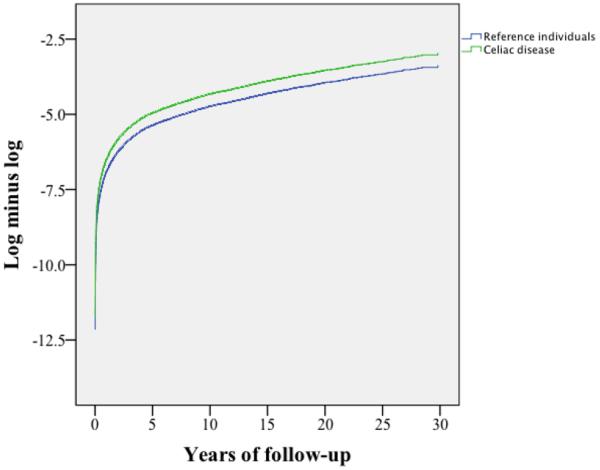

We used an internally stratified Cox regression model to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) for urticaria. The internal stratification means that we first calculated HRs for each stratum separately (a stratum consists of one individual who had undergone biopsy and up to five reference individuals) before stratum-specific risks were summarized to one overall risk estimate. In this way the analysis resembles a conditional logistic regression. We tested the proportional hazards assumption by plotting log-minus-log curves (see Appendix figure). We calculated the attributable risk percentage as (1-1/HR).

Follow-up time began at first biopsy with VA and ended with first urticaria, death, emigration or end of study period (December 31, 2009), whichever was first. Follow-up in reference individuals also ended if they had a small intestinal biopsy.

Our a priori analyses included stratifications for age (0–19; 20–39; 40–59 and 60+ years), calendar period (−1989, 1990–1999 and 2000−) and sex. Another a priori analysis involved follow-up time (<1 year 1–4.99 years and ≥5 years). The latter analysis was carried out because we have seen that patients with CD are often at high relative risks of any comorbidity in the first year after biopsy, potentially because of increased surveillance and ascertainment bias.

Secondary analyses

In subanalyses we adjusted for the following potential confounders: education and country of birth; but also for type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus and autoimmune thyroid disease (see Appendix for ICD codes) since both CD and urticaria have been linked to these autoimmune disorders.

In a second subanalysis we excluded individuals with a record of diabetic sulphonylureas (ATC code A10BB), aspirin (N02BA01), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (M01A), penicillin (J01C), clotrimazole (D01AC01), sulfonamides (J01E) and anticonvulsants (N03) since these medications may cause itch or urticaria.

We also excluded individuals with either a diagnosis of the parasitic infection ascariasis or a record in the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register[32] of anti-parasitic treatment (P02C) that could signal ascariasis infection (ascariasis may imitate urticaria). The Swedish Prescribed Drug Register[32] started in July 2005 and accounts for some 80–90% of all drug use in Sweden.

In a fourth subanalysis we excluded individuals with a diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis to eliminate the possibility that one skin disorder would lead to an increased health care contact with surveillance bias and an increased risk of misdiagnosis as urticaria.

In a fifth subanalysis we restricted our outcome to patients having urticaria and a record of either antihistamines (R06) or oral steroids (Betamethasone, H02AB01; Prednisolone, H02AB06) since these medications are the most common treatment for urticaria in Sweden.

Because some reports indicate a link between Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic urticaria[33] and because Helicobacter pylori may be misclassified as CD (or to a larger extent these patients may be investigated for CD), we also estimated the association between CD and urticaria excluding any patients with a prescription record with either a medicine combining antacids and antibiotics (ATC: A02BD) or having collected an antacid (ATC: A02) and any of three relevant antibiotics (ATC codes: J01FA09 (clarithromycin), J01XD01 (metronidazole) and J01CA04 (amoxicillin)) from the pharmacy on the same date.

Urticaria in biopsied patients without VA

In a separate analysis we examined both urticaria and chronic urticaria in individuals with CD compared with urticaria and chronic urticaria in secondary controls with intestinal inflammation (n=13,181) or those with normal mucosa but positive CD serology (n=3667). These analyses were not stratified, instead we adjusted for sex, age at biopsy and calendar period.

Temporal relationship between CD and urticaria

To evaluate the temporal relationship between CD and urticaria we examined the risk of having a diagnosis of any or chronic urticaria before CD diagnosis. This relationship was estimated by conditional logistic regression (same as the original data set for this cohort study and our study on mortality[9]).

Statistical significance was defined as 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for risk estimates not including 1.0. We used SPSS 18.0 software to perform the analyses.

Ethics

This study was approved by the regional ethical review board in Stockholm (2006/633–31/4). All data were anonymized before inclusion in the analysis.

Results

This paper was based on 28,900 individuals with CD and 143,397 reference individuals (Table 2). Year of biopsy and study entry ranged from 1969 to 2008 and the median year of first biopsy with CD was 1998. The majority of the patients were female and some 40% were diagnosed with CD as children (Table 2).

CD and risk of urticaria

Patients with CD were at increased risk of later urticaria (HR=1.51; 95%CI=1.36–1.68 based on 453 observed events vs. 300 expected in CD patients without a diagnosis of earlier urticaria) (Table 3). The absolute risk of urticaria was 140/100,000 person-years with an excess risk of 47/100,000 person-years. About 34% of all urticaria cases in patients with CD could be attributed to the underlying CD (Table 3). HRs for urticaria were constant over follow-up and the risk estimate in the first year of follow-up (HR=1.43) was similar to that after more than 5 years of follow-up (HR=1.55)(Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk of urticaria as a function of follow-up time in individuals with celiac disease.

| Follow-up | Observed events (N) | Expected events (N) | HR; 95% CI | P-value | Absolute risk/100,000 PYAR | Excess risk/100,000 PYAR | Attributable percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urticaria | |||||||

| All | 453 | 300 | 1.51; 1.36–1.68 | <0.001 | 140 | 47 | 34 |

| Excluding first year | 412 | 271 | 1.52; 1.36–1.70 | <0.001 | 212 | 73 | 34 |

| <1 year | 41 | 29 | 1.43; 1.02–2.02 | 0.038 | 144 | 43 | 30 |

| 1–4.99 years | 144 | 98 | 1.47; 1.22–1.76 | <0.001 | 135 | 43 | 32 |

| ≥5 years | 268 | 173 | 1.55; 1.36–1.78 | <0.001 | 143 | 51 | 35 |

| Chronic urticaria (≥6 weeks) | |||||||

| All | 79 | 41 | 1.92; 1.48–2.48 | <0.001 | 24 | 12 | 48 |

| Excluding first year | 76 | 37 | 2.04; 1.57–2.66 | <0.001 | 26 | 13 | 51 |

| <1 year | 3 | 4 | 0.76; 0.23–2.52 | 0.653 | 10 | −3 | −32 |

| 1–4.99 year | 37 | 13 | 2.96; 2.00–4.40 | <0.001 | 34 | 23 | 66 |

| ≥5 year | 39 | 25 | 1.58; 1.11–2.27 | 0.012 | 21 | 8 | 37 |

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, Confidence interval; PYAR, Person-years at risk.

Reference is general population comparator cohort.

#Expected number of events in patients with celiac disease was derived from the observed number of events divided by the HR.

Risk estimates were similar in men and women with CD (p=0.637 for the interaction between CD and sex with regards to urticaria) and did not differ for calendar period (p=0.997) (Table 4). The HR was lower in patients diagnosed with CD before age 20 years and neutral in patients diagnosed from 60 years and over (HR=1.03). However, differences between age groups were not significant (p=0.394).

Table 4.

Risk of urticaria in relation to demographic characteristics of patients with celiac disease.

| Subgroup | Observed events (N) | Expected events (N)* | HR; 95% CI | P-value | Absolute risk/100,000 PYAR | Excess risk/100,000 PYAR | Attributable percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||||

| Females | 310 | 201 | 1.54; 1.36–1.75 | <0.001 | 154 | 54 | 35 |

| Males | 143 | 99 | 1.45; 1.21–1.75 | <0.001 | 118 | 37 | 31 |

| Age | |||||||

| 0–19 yrs | 250 | 188 | 1.33; 1.16–1.53 | <0.001 | 172 | 43 | 25 |

| 20–39 yrs | 106 | 45 | 2.38; 1.90–2.98 | <0.001 | 179 | 104 | 58 |

| 40–59 yrs | 74 | 46 | 1.60; 1.24–2.08 | <0.001 | 100 | 37 | 38 |

| ≥60 | 23 | 22 | 1.03; 0.66–1.61 | 0.913 | 53 | 2 | 3 |

| Calendar period | |||||||

| -1989 | 67 | 34 | 1.98; 1.27–3.10 | 0.037 | 79 | 39 | 49 |

| 1990–1999 | 214 | 131 | 1.63; 1.40–1.89 | <0.001 | 134 | 52 | 39 |

| 2000–2008 | 172 | 118 | 1.46; 1.24–1.72 | <0.001 | 222 | 70 | 32 |

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, Confidence interval; PYAR, Person-years at risk.

Reference is general population comparator cohort.

Expected number of events in patients with celiac disease was derived from the observed number of events divided by the HR.

Risk of chronic urticaria

Patients with CD were at an almost twofold increased risk of chronic urticaria (HR=1.92; 95%CI=1.48–2.48 based on 79 observed events vs. 41 expected).

The absolute risk of chronic urticaria was 24/100,000 person-years with an excess risk of 12/100,000 person-years. Some 48% of all chronic urticaria cases in patients with CD could be attributed to the underlying CD (Table 5). Patients with CD were at a lower risk of chronic urticaria than the general population in the first year of follow-up, but this risk estimate was based on few cases (three observed vs. four expected cases) (Table 5). There were no differences in risk of chronic urticaria in relation to sex (p=0.290), age at CD diagnosis (p=0.145) or calendar period (p=0.665) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Risk of chronic urticaria in relation to demographic characteristics of patients with celiac disease.

| Subgroup | Observed events (N) | Expected events (N)* | HR; 95% CI | P-value | Absolute risk/100,000 PYAR | Excess risk/100,000 PYAR | Attributable percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||||

| Females | 61 | 30 | 2.03; 1.51–2.72 | <0.001 | 30 | 15 | 51 |

| Males | 18 | 11 | 1.61; 0.96–2.72 | 0.073 | 15 | 6 | 38 |

| Age | |||||||

| 0–19 yrs | 36 | 25 | 1.42; 0.98–2.06 | 0.060 | 25 | 7 | 30 |

| 20–39 yrs | 23 | 7 | 3.14; 1.90–5.17 | <0.001 | 39 | 26 | 68 |

| 40–59 yrs | 17 | 6 | 2.62; 1.48–4.66 | 0.001 | 23 | 14 | 62 |

| ≥60 | 3 | 2 | 1.21; 0.34–4.32 | 0.769 | 7 | 1 | 17 |

| Calendar period | |||||||

| -1989 | 12 | 6 | 1.90; 0.98–3.70 | 0.059 | 14 | 7 | 47 |

| 1990–1999 | 34 | 20 | 1.69; 1.15–2.48 | 0.008 | 21 | 9 | 41 |

| 2000–2008 | 33 | 15 | 2.23; 1.49–3.32 | <0.001 | 42 | 23 | 55 |

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, Confidence interval; PYAR, Person-years at risk.

Reference is general population comparator cohort.

Expected number of events in patients with celiac disease was derived from the observed number of events divided by the HR.

Secondary analyses

Adjusting for type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus did not change the risk estimates for urticaria or chronic urticaria (e.g., any urticaria: adjusted HR=1.45; 95%CI=1.31–1.62). Nor did country of birth, socioeconomic position or level of education influence the risk estimates (e.g., any urticaria: adjusted HR=1.52; 95%CI=1.37–1.69).

Excluding individuals with any record of medication that per se may cause urticaria, the HR was 1.40 for urticaria (95%CI=1.22–1.61) and 1.88 for chronic urticaria (95%CI=1.34–2.63).

Again, the risk estimates did not change after excluding individuals with a diagnosis of ascariasis or a record of using a medication signaling ascariasis (urticaria: HR=1.51; 95%CI=1.36–1.67; and chronic urticaria: HR=1.91; 95%CI=1.48–2.47; study population: CD: n=28,655 and controls: n=142,480).

Excluding individuals with a diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis did not affect the risk estimate for urticaria (HR=1.50; 95%CI=1.35–1.66) or chronic urticaria (HR=1.91; 95%CI=1.48–2.48; study population: CD: n=28,421 and controls: n=143,370).

When we excluded individuals with medication that could indicate clinical Helicobacter pylori infection, the HR for urticaria was 1.51 (95%CI=1.35–1.67; study population: CD: n=28,546 and controls: n=142,303).

Restricting our outcome to individuals in which the urticaria diagnosis was supported by a record of antihistamine or oral steroid prescription, we still found a positive association between CD and urticaria (HR=1.51; 95%CI=1.29–1.78) and chronic urticaria (HR=2.35; 95%CI=1.59–3.48).

CD patients compared with secondary reference individuals

Patients with CD were at no increased risk of urticaria compared with secondary reference individuals with either inflammation (Marsh 1–2)(HR=0.86; 95%CI=95%CI=0.71 –1.04) or normal mucosa but positive CD serology (HR=0.96; 95%CI= 0.72–1.28). Nor were there any differences in the risk of future chronic urticaria in CD when compared with inflammation (HR =1.18; 95%CI=0.73–1.90) or with normal mucosa but positive CD serology (HR=1.96; 95%CI=0.78–4.88).

Prior urticaria and CD

Patients with CD were also at increased risk of having both urticaria (OR=1.31; 95%CI=1.12–1.52) and chronic urticaria (OR=1.54; 95%CI=1.08–2.18) prior to the CD diagnosis. Excluding individuals with a diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis at some stage did not influence the ORs for prior urticaria (OR=1.31; 95%CI=1.13–1.53) and prior chronic urticaria (OR=1.52; 95%CI=1.07–2.17).

Discussion

This study found a 1.5-fold increased risk of urticaria in CD, with a slightly higher risk for chronic urticaria (HR=1.92). Further, patients were at a moderately increased risk of having a diagnosis of urticaria or chronic urticaria before CD diagnosis.

Other literature

Existing literature on CD and urticaria is (with few exceptions)[23, 24] limited to case reports.[15–17] Case reports are important for generating hypotheses but offer little evidence of a true association. Previous case-control studies[19, 23, 24] have been contradictory. The two smaller studies[23, 24] found either no association between CD and chronic urticaria or a 7.7-fold increased risk of CD in patients with urticaria. None of theses studies examined the risk of future urticaria in CD.[23, 24] Furthermore, the two studies were based on a total of only five cases with both urticaria and CD.[23, 24] Meanwhile the much larger Israeli study by Confino-Cohen et al [19] consisted of 64 patients with both CD and (chronic) urticaria, and found a 27 times increased risk of future CD in urticaria. In contrast, the current study included 453 individuals with both CD and urticaria but consistently found relative risks of around 1.5–2. The large power of our study allowed for subanalyses showing similar risk estimates in young and old CD patients, as well as in men and women. In contrast with Confino-Cohen et al [19] who found an OR for CD of 57 among female patients, and 3.9 in male patients, we found rather similar risk estimates in females and males (chronic urticaria: 2.03 and 1.61 respectively). The modest excess risk of urticaria in our study is actually more consistent with the laboratory findings of the Israeli study where 0.3% of females and 0.1% of males with chronic urticaria were positive for the highly sensitive tissue transglutaminase.[19] It is possible that using data from a health maintenance organization (Israel) vs. a national board of health and welfare (Sweden) explains part of the differences between our studies. Our use of biopsy-verified CD, as opposed to using an ICD-9-code may also have contributed to the discrepant findings. Nevertheless, both studies argue that there is an increased risk of chronic urticaria in CD.

Strengths and limitations

We based our diagnosis of CD on histopathology reports with VA. Earlier validation has shown that 95% of all VA is CD, which is a higher positive predictive value than having a physician-assigned diagnosis of CD in the Swedish Patient Register.[26] Swedish pathologists will correctly classify 90% of all samples with VA.[29] The number of small intestinal tissue specimens constituting the basis for a histopathological report in Sweden is three,[30], which should rule in 95% of all CD cases.[34] When two independent researchers manually reviewed more than 1500 biopsy reports with data on VA and inflammation, other diagnoses than CD were very uncommon in the reports (the most common non-celiac diagnosis in VA was inflammatory bowel disease, occurring in 0.3% of the reports).[29] Biopsy reports also have a high sensitivity for diagnosed CD: more than 96% of all gastroenterologists and pediatricians will biopsy at least 90% of patients with suspected CD.

We are not aware of any study validating urticaria in the Swedish Patient Register. Most diagnoses in this Register have a positive predictive value of 85–95%.[26] We did, however, carry out several sensitivity analyses with no change in the risk estimates (e.g., restricting our outcome to urticaria remedied by antihistamines or oral steroids but also excluding patients with ascariasis and dermatitis herpetiformis). Finally, the outcome of chronic urticaria per se required at least two health care contacts for urticaria, and with that comes an increased specificity. Importantly, the HRs were higher for chronic urticaria than urticaria in general. Misclassification is therefore unlikely to explain the positive association between CD and urticaria in this study. A limitation of our paper is that we did not have data on geographic origin of CD and were therefore unable to explore regional variations in the CD-urticaria relationship. Such an analysis might otherwise have added to the understanding of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of the two diseases.

Rash and pruritus may occur in a number of disorders but many of these have distinct ICD codes and are not coded as “urticaria”. These disorders include allergic contact dermatitis, angioneurotic edema, hereditary angioedema, giant urticaria, Quincke edema, serum urticaria and neonatal urticaria. We did not have data on several laboratory tests (e.g., IgE levels, skin prick test, blood count or C1q levels) in patients with urticaria and thus we could not distinguish idiopathic urticaria from other forms of urticaria. On the other hand, patients with CD are likely more interested in their risk of developing future urticaria or chronic urticaria than whether they will develop idiopathic urticaria or other forms of urticaria. The overall absolute risk of urticaria was low. In CD patients without a prior history of urticaria about 1 in 700 CD patients each year would have an incident diagnosis of urticaria (140/100,000 person-years).

Finally, a main strength of our paper is its ability to adjust for other autoimmune diseases. Doing so had only a marginal effect on the risk estimates, suggesting that the existence of other autoimmune diseases cannot explain the positive findings in our study.

Potential mechanisms of action

We can only speculate as to the exact underlying mechanism for the positive association between CD and urticaria, but given that the association occurred both before and after CD diagnosis, we believe CD and urticaria are disorders that may share common risk factors. We have previously shown that CD is associated with allergy and atopic disorders.[35] In fact, the risk estimate for urticaria was almost identical to that for asthma in patients with biopsy-verified CD.[35] We were unable to examine the effect of a GFD in that we lacked individual-based information on GFD in our patients. However, in a random subset of patients from our CD cohort, 83% were adherent to a GFD.[29]

Although the vast majority of patients with CD are HLA-DQ2+, among those who are not DQ2+ many will be positive for DRB1*04, which has been linked to chronic urticaria.[36] Finally, urticaria is characterized by both Th2 and Th1 components. Although CD was previously regarded as almost exclusively a Th1 disease, a recent paper reported a cytokine pattern consistent with both Th1 and Th2.[37]

The finding of no difference in the risk of urticaria between individuals with CD and those with only minor histopathology could be an indication that macroscopic intestinal changes are not required for urticaria in CD. Early CD without VA is characterized by increased permeability leading to antigenic exposures within the gut that could possibly result in sensitization and urticaria. A general increase in permeability may also explain why the risk of urticaria in CD was not higher than in individuals with inflammation or normal mucosa but positive CD serology (potentially early CD). In the meantime, the high prevalence of urticaria also in patients with positive serology (but normal mucosa) supports serological screening for CD in patients with urticaria.[23]

In conclusion, we found an increased risk of urticaria and chronic urticaria in patients with CD, which occurred both before and after CD diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding JFL was supported by grants from the Swedish Society of Medicine, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Celiac Society, and the Fulbright Commission.

JAM: The National Institutes of Health – DK071003 and DK057892.

None of the funders had any influence on this study.

JAM: Grant support: Alba Therapeutics (>$50,000); Advisory board: Alvine Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (<$10,000), Nexpep (<$10,000), Consultant (none above 10,000 USD): Ironwood, Inc., Flamentera, Actogenix, Ferring Research Institute inc., Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Vysera Biomedical, 2G Pharma, Inc, ImmunosanT, Inc and Shire US Inc.

Abbreviations used in this article

- CD

Celiac disease

- CI

Confidence Interval

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICD

International Classification of Disease [codes]

- OR

Odds ratio

- VA

Villous atrophy

- GFD

gluten-free diet.

APPENDIX

Log-minus-log curve: The parallel lines mean the proportional hazards assumption is valid.

ICD (international classification of disease) codes

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

Before 1997, the ICD coding for diabetes (ICD-7: 260, ICD-8: 250, ICD-9: 250) did not distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. We defined individuals with type 1 diabetes as those who were ≤30 years of age at their first hospitalization for diabetes (ICD-7-ICD-10). ICD-10: E10.

Autoimmune thyroid disease

Autoimmune thyroid disease was defined as follows: ICD-7: 252.00, 252.01, 252.02, 253.10, 253.19, 253.20, 253.29, 254.00, ICD-8: 242.00, 242.09, 244, 245.03, ICD-9: 242A, 242X, 244X, 245C, 245W, ICD-10: E03.5, E03.9, E05.0, E05.5, E05.9, E06.3, E06.5.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis was defined as follows: ICD-8: 712,3, 714,93, ICD-9: 714, ICD-10: M05, M06.

Lupus erythematosus

Lupus erythematosus was defined as follows: ICD-7; 705.4 and 456.2; ICD-8: 695.4 and 734.10; ICD-9: 373, 695E and 710A; ICD-10: L93 and M32

Ascariasis

Ascariasis was defined as follows: ICD-7; 130.0; ICD-8: 127.0; ICD-9: 127A; ICD-10: B77.

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis was defined as follows: ICD-7; 704.0; ICD-8: 693.99; ICD-9: 694A; ICD-10: L13.0.

Footnotes

Details of ethics approval: This project (2006/633-31/4) was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm on June 14, 2006.

Conflict of Interest (The other authors have no conflict of interest to declare).

References

- 1.Zuberbier T, Bindslev-Jensen C, Canonica W, Grattan CE, Greaves MW, Henz BM, et al. EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2006 Mar;61(3):316–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria: pathogenesis and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Sep;114(3):465–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.02.049. quiz 75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allergy Statistics 2012 [cited 2012 Feb 2.]; Available from: http://www.aaaai.org/about-the-aaaai/newsroom/allergy-statistics.aspx.

- 4.Greaves MW. Chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jun 29;332(26):1767–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506293322608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzpatrick TB, Wolf K. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine: McGraw-Hill Professional. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Donnell BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J, Morgan M, Greaves MW. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 1997 Feb;136(2):197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dube C, Rostom A, Sy R, Cranney A, Saloojee N, Garritty C, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in average-risk and at-risk Western European populations: a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2005 Apr;128(4 Suppl 1):S57–67. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludvigsson JF, Green PH. Clinical management of coeliac disease. J Intern Med. 2011 Jun;269(6):560–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludvigsson JF, Montgomery SM, Ekbom A, Brandt L, Granath F. Small-intestinal histopathology and mortality risk in celiac disease. JAMA. 2009 Sep 16;302(11):1171–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West J, Logan RF, Smith CJ, Hubbard RB, Card TR. Malignancy and mortality in people with coeliac disease: population based cohort study. Bmj. 2004 Sep 25;329(7468):716–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38169.486701.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green PH, Fleischauer AT, Bhagat G, Goyal R, Jabri B, Neugut AI. Risk of malignancy in patients with celiac disease. Am J Med. 2003 Aug 15;115(3):191–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catassi C, Fabiani E, Corrao G, Barbato M, De Renzo A, Carella AM, et al. Risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in celiac disease. Jama. 2002;287(11):1413–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludvigsson JF, Ludvigsson J, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Celiac Disease and Risk of Subsequent Type 1 Diabetes: A general population cohort study of children and adolescents. Diabetes Care. 2006 Nov;29(11):2483–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elfstrom P, Montgomery SM, Kampe O, Ekbom A, Ludvigsson JF. Risk of thyroid disease in individuals with celiac disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Oct;93(10):3915–21. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hautekeete ML, DeClerck LS, Stevens WJ. Chronic urticaria associated with coeliac disease. Lancet. 1987 Jan 17;1(8525):157. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91986-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peroni DG, Paiola G, Tenero L, Fornaro M, Bodini A, Pollini F, et al. Chronic urticaria and celiac disease: a case report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010 Jan-Feb;27(1):108–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haussmann J, Sekar A. Chronic urticaria: a cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006 Apr;20(4):291–3. doi: 10.1155/2006/871987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meneghetti R, Gerarduzzi T, Barbi E, Ventura A. Chronic urticaria and coeliac disease. Arch Dis Child. 2004 Mar;89(3):293. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.037259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Confino-Cohen R, Chodick G, Shalev V, Leshno M, Kimhi O, Goldberg A. Chronic urticaria and autoimmunity: associations found in a large population study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 May;129(5):1307–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abenavoli L, Proietti I, Zaccone V, Gasbarrini G, Addolorato G. Celiac disease: from gluten to skin. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2009 Nov;5(6):789–800. doi: 10.1586/eci.09.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedrosa Delgado M, Martin Munoz F, Polanco Allue I, Martin Esteban M. Cold urticaria and celiac disease. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2008;18(2):123–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ombrello MJ, Remmers EF, Sun G, Freeman AF, Datta S, Torabi-Parizi P, et al. Cold urticaria, immunodeficiency, and autoimmunity related to PLCG2 deletions. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jan 26;366(4):330–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caminiti L, Passalacqua G, Magazzu G, Comisi F, Vita D, Barberio G, et al. Chronic urticaria and associated coeliac disease in children: a case-control study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005 Aug;16(5):428–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabrielli M, Candelli M, Cremonini F, Ojetti V, Santarelli L, Nista EC, et al. Idiopathic chronic urticaria and celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2005 Sep;50(9):1702–4. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2919-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2007 Oct 25;357(17):1731–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011 Jun 9;11(1):450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(11):659–67. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity (`celiac sprue') Gastroenterology. 1992;102(1):330–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludvigsson JF, Brandt L, Montgomery SM, Granath F, Ekbom A. Validation study of villous atrophy and small intestinal inflammation in Swedish biopsy registers. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009 Mar 11;9(1):19. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ludvigsson JF, Brandt L, Montgomery SM. Symptoms and signs in individuals with serology positive for celiac disease but normal mucosa. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johannesson I. New Possibilities and Better Quality. Statistics Sweden; Örebro: 2002. The Total Population Register of Statistics Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, Leimanis A, Otterblad Olausson P, Bergman U, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register--opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007 Jul;16(7):726–35. doi: 10.1002/pds.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wustlich S, Brehler R, Luger TA, Pohle T, Domschke W, Foerster E. Helicobacter pylori as a possible bacterial focus of chronic urticaria. Dermatology. 1999;198(2):130–2. doi: 10.1159/000018088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pais WP, Duerksen DR, Pettigrew NM, Bernstein CN. How many duodenal biopsy specimens are required to make a diagnosis of celiac disease? Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 Jun;67(7):1082–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ludvigsson JF, Hemminki K, Wahlstrom J, Almqvist C. Celiac disease confers a 1.6-fold increased risk of asthma: A nationwide population-based cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Feb 9;127(4):1071–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bozek A, Krajewska J, Filipowska B, Polanska J, Rachowska R, Grzanka A, et al. HLA status in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;153(4):419–23. doi: 10.1159/000316354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manavalan JS, Hernandez L, Shah JG, Konikkara J, Naiyer AJ, Lee AR, et al. Serum cytokine elevations in celiac disease: Association with disease presentation. Hum Immunol. 2009 Jan;71(1):50–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.09.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corazza GR, Villanacci V. Coeliac disease. J Clin Pathol. 2005 Jun;58(6):573–4. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.023978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.