Abstract

Background

Most young adult women who smoke marijuana also drink alcohol. Marijuana-related problems are associated with marijuana use frequency. We hypothesized that increased alcohol use frequency potentiates the association between frequency of marijuana use and marijuana-related problem severity.

Methods

We recruited women age 18–24 who smoked marijuana at least monthly and were not treatment-seeking. Marijuana and alcohol use were measured using the Timeline Followback method. Problems associated with marijuana use were assessed using the Marijuana Problems Scale.

Findings

Participants (n=332) averaged 20.5 (± 1.8) years of age, were 66.7% non-Hispanic White, and reported using marijuana on 51.5 (± 30.6) and alcohol on 18.9 (± 16.8) of the 90 previous days. Controlling for education, ethnicity, years of marijuana use, and other drug use, frequency of marijuana use (b = .22, p < .01) and frequency of alcohol use (b = 0.13, p < .05) had statistically significant positive effects on marijuana problem severity. In a separate multivariate model, the linear by linear interaction of marijuana by alcohol use frequency was statistically significant (b = 0.18, p < .01) consistent with the hypothesis.

Conclusions

Concurrent alcohol use impacts the experience of negative consequences from marijuana use in a community sample of young women. Discussions of marijuana use in young adults should consider the possible potentiating effects of alcohol use.

Keywords: Marijuana, alcohol, young adults, drug consequences, women

Introduction and Background

Marijuana use has been linked to a host of adverse consequences (Kalant, 2004). It can have deleterious respiratory effects (Moore, Auguston, Moser, & Budney, 2005; Taylor, et al., 2002), adversely impact cognitive functioning (Schweinsburg, et al., 2005; Solowij, et al., 2002), lead to or exacerbate mental health problems (Hall & Degenhardt, 2009; Patton, et al., 2002) and increase rates of accidents and injury (Hall & Babor, 2000; Macdonald, et al., 2003; Woolard, et al., 2003). Additionally, marijuana use is associated with risky sexual behavior such as increased sexual activity or inconsistent condom use (Anderson & Stein, 2011; Hingson, Strunin, Berlin, & Heeren, 1990; Lowry, et al., 1994; Shrier, Emans, Woods, & DuRant, 1997), and women who use marijuana may be at increased risk for sexual assault (Messman-Moore, Coates, Gaffey, & Johnson, 2008). Rates of past month marijuana use have generally increased among young women over the past twenty years (Wallace, et al., 2003), and women are often “early initiators,” which can lead to more extensive marijuana use (Flory, Lynam, Milich, Leukefeld, & Clayton, 2004). Following alcohol, marijuana is second most frequently used substances among young adults, with 19% of those 18–25 reporting past month marijuana use (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012) and nearly 35% reporting use in the past year (Johnson, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2013).

Between 75–95% of marijuana users also drink alcohol (Barrett, Darredeau, & Pihl, 2006; Collins, Ellickson, & Bell, 1998; Pape, Rossow, & Storvoll, 2009). Among college-aged drinkers, lifetime and past year use of marijuana increased as level of alcohol consumption increased (O’Grady, Arria, Fitzelle, & Wish, 2008). In a large general population sample, 58% of those with a past 12-month DSM-IV cannabis use disorder also had an identified alcohol use disorder (Stinson, et al., 2005). Alcohol and marijuana are often used concurrently over the same time period (i.e. past 90 days), and occasionally together on the same day (simultaneous use) (Barrett, et al., 2006; Earleywine & Newcomb, 1997; Midanik, Tam, & Weisner, 2007; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009).

The deleterious effects of concurrent marijuana and alcohol use seem to be far greater than the effects from either substance used alone. Among current drinkers, those who also use marijuana experienced more problems than those who used alcohol alone (Shillington & Clapp, 2001). Concurrent alcohol and marijuana users reported greater alcohol dependence, social consequences, and depression (Midanik, et al., 2007). Pacek et al (Pacek, Malcolm, & Martins, 2012) reported that use of alcohol and marijuana could lead to increases in arrests, sexually transmitted infections, and depression in a large national sample; however, these results were contingent on race and ethnicity. When used on the same occasion, there is the high level of impairment in motor vehicle operation from combining marijuana with even low levels of alcohol (Robbe, 1998).

Yet current marijuana users often do not perceive their use to be risky (Kilmer, Hunt, Lee, & Neighbors, 2007) and in general report few problems from their use (Stephens, et al., 2004). While those who actively seek treatment do report more marijuana-related problems (Stephens, Roffman, & Curtin, 2000), non-treatment seekers often have patterns of marijuana use that far exceed the minimum criteria for abuse and dependence (Stephens, Roffman, Fearer, Williams, & Burke, 2007; Stephens, et al., 2004), and increased frequency of use as well as intensity of intoxication increases associated problems (Walden & Earleywine, 2008).

To our knowledge the potential dual effect of concurrent alcohol and marijuana use on adverse marijuana-related consequences has not been investigated in a sample of marijuana users. The extant literature has explored this relationship in samples of alcohol users who may also use marijuana, but has not examined a sample that uses marijuana with the intent to explore the effects of alcohol above and beyond marijuana. The purpose of the current investigation is to explore concurrent marijuana and alcohol use in a community sample of young adult, non-treatment seeking, female marijuana users. Specifically, we hypothesize that increased frequency of alcohol use will potentiate the association between frequency of marijuana use and marijuana related problem severity even if alcohol and marijuana are not used simultaneously.

Methods

The study sample was recruited from the community through newspaper and radio advertisements for a “research study about the health behaviors of young adult women”. A comprehensive description of study methodology is described elsewhere (Stein, Hagerty, Herman, Phipps, & Anderson, 2011). Interested women were screened over the phone, and those eligible were invited to complete informed consent, and an in-person assessment. The MAPLE study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Butler Hospital.

Inclusion criteria included: 1) smoking marijuana at least 3 times in the past three months, 2) aged 18–24, 3) living within 20 miles of Providence RI and planning to remain in the geographic area for the next 6 months, 4) English comprehension, 5) not meeting criteria for substance dependence other than marijuana, alcohol, or nicotine within the past year.

Between January 2005 and May 2009, 1,728 individuals were screened by phone and 1,213 were excluded for not meeting eligibility criteria for the following reasons: had not smoked marijuana in the last 3 months (n=958) or marijuana use frequency was too low (n=60); did not meet secondary criteria (e.g., were pregnant, non-English speaking, older than 24, lived too far from the study site or were drug dependent, n=140); did not provide enough information to determine eligibility (n=55). Of the 515 eligible women, 183 refused or were unable to enroll. A total of 332 women were enrolled in the trial. Eligible persons provided informed consent and were enrolled in a randomized clinical trial comparing a 2-session motivationally-focused intervention (MI) to assessment only (AO). Participants were compensated $30 for the baseline assessment, an hour-long, researcher-administered questionnaire, on which this analysis is based.

Measures

Background Characteristics

Age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and age of first marijuana use were assessed through self-report.

Substance Use History

Past 90-day marijuana and alcohol use was assessed using the Timeline Follow-Back – TLFB (Sobell, Maisto, Sobell, & Cooper, 1979; Sobell & Sobell, 1992), a calendar based method to measure day-by-day substance use. Problems associated with marijuana use were assessed using the Marijuana Problems Scale – MPS (Stephens, et al., 2000; Stephens, Roffman, & Simpson, 1994). This 19-item scale asks participants to rate a list of marijuana-related problems experienced in the previous 90 days on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (no problem) to 2 (serious problem). Example items include “Has marijuana use caused you: Problems between you and your friends; Difficulty sleeping; Lowered self-esteem; To take risks, like driving a car while under the influence.” Possible scores ranged from 0–38. Each problem can also be scored as either present or absent and summed to form a total problem count, which is how the scale creators originally presented their findings (Stephens, et al., 2000; Stephens, et al., 2004). We present the data both ways, however, we use mean score on the 0–38 scale in the analyses to best capture the continuous range and severity of marijuana problems. Internal consistency for the MPS in this cohort was .79. Other samples have reported alphas of .90 and .84 (Stephens, et al., 2000; Stephens, et al., 2004). Past 90-day opioid and cocaine use were assessed using the Addiction Severity Index (McLellen, et al., 1992).

Analytic Methods

We present descriptive statistics to summarize the characteristics of the cohort. OLS regression was used to test the hypothesis that frequency of alcohol use potentiates the effect of marijuana use frequency on marijuana problem severity. We present two multivariate regression models. Model 1 includes main effects only and evaluates the linear association of marijuana and alcohol use frequency with marijuana problem severity after controlling for planned covariates. Control variables included educational attainment, ethnicity, years of regular marijuana use, and recent (past 90 days) use of cocaine or opioids. Age was not included because of limited variability and a substantial correlation (r = .55, p < .01) with years of regular marijuana use. Model 2 extends Model 1 by including the linear by linear interaction effect of marijuana and alcohol use frequency. A significant first-order interaction is consistent with the hypothesis that frequency of alcohol use potentiates the effect of marijuana use frequency on marijuana problem severity. All continuous variables were standardized to zero mean and unit variance prior to model estimation. The reported coefficients for continuous predictor variables are fully standardized; the coefficients reported for categorical predictors are y-standardized.

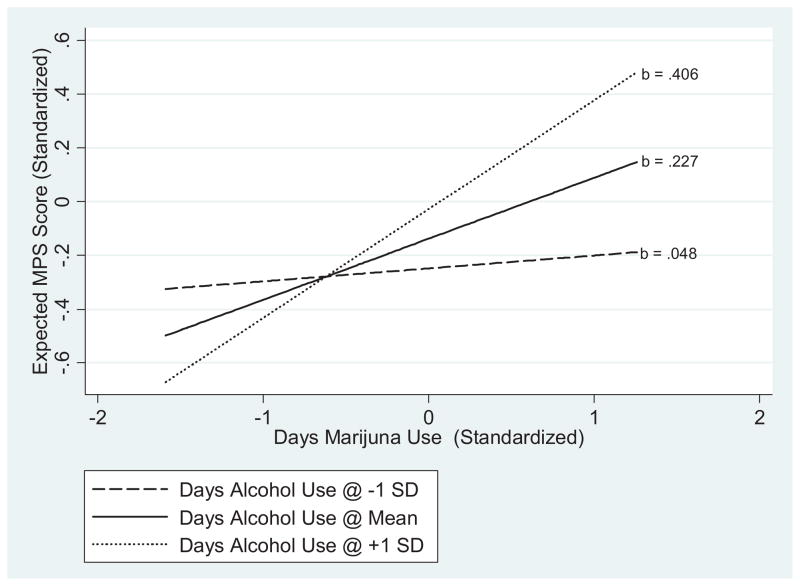

To facilitate interpretation, we plotted the expected linear association of marijuana use frequency and marijuana problem severity at 3 values of alcohol use frequency. We chose the values −1 SD below the mean, the mean, and +1 SD above the mean to represent low frequency, average frequency, and high frequency alcohol use. Though somewhat arbitrary, the choice of these values provides a convenient mechanism to explicate the statistical interaction.

Results

Participants averaged 20.5 (± 1.8) years of age, 225 (66.7%) were non-Hispanic White, 35 (10.5%) were African-American, 38 (11.4%) were Hispanic, and 34 (10.4%) were of other racial or ethnic origins (Table 1). The mean duration of regular marijuana use was 3.9 (± 2.6) years. On average, participants reported using marijuana on 51.5 (± 30.6) and alcohol on 18.9 (± 16.8) of the 90 days prior to baseline. A total of 30,657 daily reports were available from the 90-day TLFB. Of these, participants reported using both alcohol and marijuana on 14.2% of days, using marijuana but not alcohol on 42.5% of days, using only alcohol but not marijuana on 6.8% of days, and not using either substance on 36.5% of days. The mean score on the marijuana problem severity scale was 6.1 (± 1.8, Median = 5.0) and mean problem count was 4.08 (±3.24, Median 3.0). Forty-seven (14.2%) participants reported any use of cocaine and 54 (16.3%) reported any use of opioids in the 90-days prior to baseline (Table 1).

Table 1.

Background Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics (n = 332).

| Mean (± SD) | Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 20.5 (1.8) | 20.0 | 18 – 24 |

| Years Regular Marijuana Use | 3.9 (2.6) | 4.0 | 0 – 15 |

| Days (Past 90) Used Marijuana | 51.5 (30.6) | 0.57 | 3 – 90 |

| Days (Past 90) Used Alcohol | 18.9 (16.8) | 14.5 | 0 – 81 |

| Marijuana Problem Severity (MPS) | 6.1 (5.6) | 5.0 | 0 – 28 |

| n (%)

|

|||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 225 (67.7%) | ||

| African – American | 35 (10.5%) | ||

| Hispanic | 38 (11.4%) | ||

| Other Minority | 34 (10.2%) | ||

| Recent (Past 90 Days) Cocaine Use (Yes) | 47 (14.2%) | ||

| Recent (Past 90 Days) Opioid Use (Yes) | 54 (16.3%) |

Model 1 (Table 2) gives the adjusted linear effect of marijuana use frequency and alcohol use frequency on marijuana problem severity; Model 2 extends Model 1 by including the linear by linear interaction of marijuana and alcohol use frequency. After adjusting for other covariates in the model, frequency of marijuana use (b = .22, p < .01) and frequency of alcohol use (b = 0.13, p < .05) had statistically significant positive effects on marijuana problem severity (Model 1). The linear by linear interaction of marijuana by alcohol use frequency was statistically significant (b = 0.18, p < .01) (Model 2). As comparison, the R2 for these two models (Table 2) indicates the linear by linear interaction uniquely accounted for about 3.0% of the total variance in marijuana problem severity.

Table 2.

OLS Regression Models Estimating the Adjusted Effects of Marijuana Use Frequency, Alcohol Use Frequency, and the Linear by Linear Interaction of Marijuana and Alcohol Use Frequency on Marijuana Problem Severity (n = 332).

| Predictor | MODEL 1 ba (95% CI) |

MODEL 2 ba (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Education (Yrs.) | −0.07 (−0.18; 0.05) | −0.06 (−0.18; 0.05) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | −0.04 (−0.39; 0.31) | −0.03 (−0.37; 0.32) |

| African American | 0.36 (−0.09; 0.81) | 0.34 (−0.10; 0.78) |

| Hispanic | 0.58** (0.14; 1.02) | 0.53* (0.10; 0.97) |

| Other [REF] | ||

| Yrs. Regular Marijuana Smoking | 0.04 (−0.07; 0.14) | 0.04 (−0.07; 0.14) |

| Recent Cocaine Use (Yes) | −0.07 (−0.37; 0.23) | −0.07 (−0.37; 0.23) |

| Recent Opiate Use (Yes) | 0.22 (−0.07; 0.51) | 0.21 (−0.07; 0.50) |

| Days Marijuana Use | 0.22** (0.12; 0.33) | 0.23** (0.12; 0.33) |

| Days Alcohol Use | 0.13* (0.02; 0.24) | 0.11* (0.00; 0.22) |

| Marijuana X Alcohol Interaction | NA | 0.18** (0.07; 0.28) |

| Intercept | −0.10 | −0.11 |

|

|

||

| Model R2 = | .135** | .165** |

p < .05,

p < .01

All continuous variables were standardized to zero mean and unit variance prior to analysis. Coefficients for continuous covariates are fully standardized, coefficients for categorical predictors are y-standardized.

Figure 1 gives a plot of this interaction. Specifically we plot the expected linear association between marijuana use frequency and marijuana problem severity at relatively high (+1 SD above the mean), relatively low (−1 SD below the mean), and average (mean) levels of alcohol frequency. The expected linear effect of marijuana use frequency on marijuana problem severity is weak (b = .048) when alcohol use frequency is low, moderate (b = .227) at mean alcohol use frequency, and stronger (b = .406) when alcohol use frequency is 1 SD above the mean. In the metric of the original marijuana problems severity scale, a 1 standard deviation increase in marijuana use frequency is associated with an increase of about .27 points, 1.27 points, and 2.77 points among persons at −1 SD, at the mean, and at +1 SD above the mean, respectively, with respect to frequency of alcohol use.

Figure 1.

Expected Linear Effect of Marijuana Use Frequency on Marijuana Problem Severity at Three Values on Days Using Alcohol.

Statistically significant (F3,321 = 4.84, p < .01) differences in marijuana problem severity were also observed by ethnicity. Here we report statistics from Model 2, but note that Model 1 gave consistent results regarding the associations of planned covariates with marijuana problem severity. Hispanics had significantly (t321 = 2.41, p < .05) higher mean marijuana problem severity scores than those with other racial or ethnic identities (Table 2). Additional comparisons, not shown in Table 2, indicated that non-Hispanic Whites reported significantly lower problem severity scores than African-Americans (t321 = 2.07, p < .05) or Hispanics (t321 = 3.40, p < .01). Marijuana problem severity was not associated significantly with any of the other covariates included in the multivariate models.

Conclusions and Discussion

In this population of young adult women who use marijuana, we found empirical support for the hypothesis that frequency of alcohol use potentiates the association between marijuana use frequency and marijuana problem severity when alcohol and marijuana are used concurrently. Consistent with previous findings, over 95% of our sample of marijuana users also drank alcohol (Barrett, et al., 2006; Collins, et al., 1998; Pape, et al., 2009) in the past 90-days. Marijuana problem severity was related to level of concurrent alcohol use, which is also consistent with the extant literature derived from samples of alcohol users (Midanik, et al., 2007; Shillington & Clapp, 2001). This finding is especially important given that nearly 60% of those with a marijuana use disorder nationally also have an alcohol use disorder (Stinson, et al., 2005), and 70% of teenagers who drink heavily use drugs concurrently (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012). Because marijuana and alcohol are both being used during a given time period, here ninety days, any discussion about the adverse effects of marijuana use should also consider the possible potentiating effects of alcohol use. These data provide evidence that these two substances do not have to be used on the same occasion to interact and therefore care should be taken by clinical providers and researchers to collect accurate information about negative consequences and harmful effects when assessing substance use.

Interestingly, marijuana problems varied in our sample by ethnicity. Previous exploration of concurrent marijuana and alcohol use has also found differences by ethnicity, however, their pattern of results were different (Pacek, et al., 2012). Where others have found greatest concurrent use and problems in African American individuals, our findings do not replicate this result. Operational definition of substance use problems may explain these differences, but disparate findings suggest a more systematic investigation of the role of race and ethnicity in concurrent substance use and perceived problems is warranted.

Overall endorsement of marijuana problems was low in the current sample. However, the mean problems count is similar to, or higher than, those found in other non-treatment seeking adults (Harrington, et al., 2012; Walden & Earleywine, 2008), although it is lower than problem counts found in treatment seeking samples (Stephens, et al., 2000; Stephens, et al., 2004). Previous work with this sample has shown that quit desire is related to marijuana problem severity (Caviness, et al., 2013). Given that those seeking treatment endorse more problems from their use, researchers and clinical providers may be able to inquire about the negative aspects of marijuana use as a way to initiate a discussion of desire to quit. The present findings highlight the role that concurrent alcohol use plays in exacerbating the negative consequences of marijuana use.

This study has important strengths. First, it sampled a community sample of young adult women. Previous research has found significant gender differences, with men far more likely than women to report concurrent and simultaneous use of marijuana and alcohol (Collins, et al., 1998; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009), so replicating those findings in this population adds to our understanding of how these two substances are used together. Second, we recruited a sample of marijuana users and assessed their alcohol use, instead of the more common sampling of alcohol users who may or may not also use marijuana. Finally, our outcome, the Marijuana Problems Scale, asked specifically about problems related to marijuana use, allowing us to assess the impact of alcohol added to marijuana use. Previous studies have used less specific problem scales, or have not specified the substance to which problems are attributed. Our design allows for the examination of alcohol’s involvement above and beyond that of frequent marijuana use.

There are important limitations to this study. First, these data are cross-sectional. Therefore we cannot definitively establish a causal link between concurrent alcohol and marijuana use and increased marijuana problems. Second, we did not consider the life impact of having specific marijuana-related problems. It is possible that some participants endorsed experiencing items on the Marijuana Problems Scale without feeling that they were impairing their daily lives, or failed to endorse an item because they did not perceive it as causing a problem. Third, with a sample of young adult women, our findings may not generalize to younger adolescents, older women, or men. Fourth, we did not collect data related to socioeconomic status (SES), such as maternal educational attainment, or family income level (as many of these women are still in school, or dependent on their parents), and therefore were unable to test its relationship to marijuana and alcohol use in this sample. Previous work suggests low SES may be related to increased marijuana and alcohol risk behavior (Lemstra, et al., 2008). Fifth, we did not collect data on binge drinking, and therefore cannot comment on its impact on marijuana-related problems. However, frequency of use, the alcohol measure we used, may be serving as a surrogate for heavier use. Sixth, we did not analyze the impact of mental health conditions on alcohol and marijuana use. It is possible women who have greater mental health problems are self-medicating with alcohol and/or marijuana and may attribute more problems to their use. Finally, because the use of both of these substances during the past 90 days is nearly universal in this cohort (as is the combined use on at least one day), some mis-attribution of “marijuana-related” problems may have occurred.

Implications for Practice and/or Policy

This study highlights the impact of concurrent alcohol use on the experience of negative consequences from marijuana use in a sample of young women. Given the frequent use of both marijuana and alcohol any discussion about marijuana use in young people must also consider the possible additive and potentiating effects of alcohol use frequency, even if individuals are not using the two substances simultaneously. Considering marijuana use in isolation, whether for intervention, treatment, or policy, is likely not reflective of reality of use, especially among young adults (Barrett, et al., 2006; Collins, et al., 1998; Pape, et al., 2009; Stinson, et al., 2005). Treatment providers and those intervening with at-risk marijuana users should assess for concurrent alcohol use, including heavy drinking. Alternatively, given that many colleges, gynecologic care providers, and other health care services young adults may access, routinely screen for alcohol use, adding a brief assessment of marijuana use would be an easy, cost-effective, way to identify a population that may be at increased risk for negative outcomes. Additionally, given the potential relationship between negative consequences from use and desire to quit (Caviness, et al., 2013; Ellingstad, Sobell, Sobell, Eickleberry, & Golden, 2006; Weiner, Sussman, McCuller, & Lichtman, 1999), second level screening may allow for intervention on problematic substance use.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant R01 DA018954. Dr. Stein is a recipient of NIDA Award K24 DA000512.

Dr. Stein had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Trial registered at clinicaltrials.gov; Clinical Trial #NCT00227864

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Michael D. Stein, Email: Michael_Stein@brown.edu.

Celeste M. Caviness, Email: ccaviness@butler.org.

Bradley J. Anderson, Email: bjanderson@butler.org.

References

- Anderson B, Stein M. A behavioral decision model testing the association of marijuana use and sexual risk among young adult women. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(4):875–884. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9694-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett SP, Darredeau C, Pihl RO. Patterns of simultaneous polysubstance use in drug using university students. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(4):255–263. doi: 10.1002/hup.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviness CM, Hagerty CE, Anderson BJ, de Dios MA, Hayaki J, Herman D, et al. Self-Efficacy and Motivation to Quit Marijuana Use among Young Women. The American Journal on Addictions. 2013;22(4):373–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Ellickson PL, Bell RM. Simultaneous polydrug use among teens: prevalence and predictors. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1998;10(3):233–253. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earleywine M, Newcomb MD. Concurrent versus simultaneous polydrug use: prevalence, correlates, discriminant validity, and prospective effects on health outcomes. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;5(4):353–364. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingstad TP, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Eickleberry L, Golden CJ. Self-change: A pathway to cannabis abuse resolution. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(3):519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16(1):193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Babor T. Cannabis use and public health: assessing the burden. Addiction. 2000;95(4):485–490. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9544851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 2009;374(9698):1383–1391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington M, Baird J, Lee C, Nirenberg T, Longabaugh R, Mello MJ, et al. Identifying subtypes of dual alcohol and marijuana users: a methodological approach using cluster analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(1):119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Strunin L, Berlin BM, Heeren T. Beliefs about AIDS, use of alcohol and drugs, and unprotected sex among Massachusetts adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80(3):295–299. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2012: Volume 2, College students and adults ages 19–50. Ann Arbor, MI: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kalant H. Adverse effects of cannabis on health: an update of the literature since 1996. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2004;28(5):849–863. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer JR, Hunt SB, Lee CM, Neighbors C. Marijuana use, risk perception, and consequences: is perceived risk congruent with reality? Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):3026–3033. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemstra M, Bennett NR, Neudorf C, Kunst A, Nannapaneni U, Warren LM, et al. A meta-analysis of marijuana and alcohol use by socio-economic status in adolescents aged 10–15 years. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2008;99(3):172–177. doi: 10.1007/BF03405467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry R, Holtzman D, Truman B, Kann L, Collins J, Kolbe L. Substance use and HIV-related sexual behaviors among US high school students: are they related? American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(7):1116–1120. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald S, Anglin-Bodrug K, Mann R, Erickson P, Hathaway A, Chipman M, et al. Injury risk associated with cannabis and cocaine use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;72(2):99–115. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellen A, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, et al. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Coates AA, Gaffey KJ, Johnson CF. Sexuality, substance use, and susceptibility to victimization: risk for rape and sexual coercion in a prospective study of college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(12):1730–1746. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Tam TW, Weisner C. Concurrent and simultaneous drug and alcohol use: results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90(1):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore B, Auguston E, Moser R, Budney A. Respiratory effects of marijuana and tobacco use in a U.S. sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(1):33–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady KE, Arria AM, Fitzelle DM, Wish ED. Heavy Drinking and Polydrug Use among College Students. Journal of Drug Issues. 2008;38(2):445–466. doi: 10.1177/002204260803800204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek LR, Malcolm RJ, Martins SS. race/ethnicity differences between alcohol, marijuana, and co-occurring alcohol and marijuana use disorders and their association with public health and social problems using a national sample. The American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21(5):435–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape H, Rossow I, Storvoll EE. Under double influence: assessment of simultaneous alcohol and cannabis use in general youth populations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;101(1–2):69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Lynskey M, Hall W. Cannabis use and mental health in young people: cohort study. BMJ. 2002;325(7374):1195–1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbe H. Marijuana’s impairing effects on driving are moderate when taken alone but severe when combined with alcohol. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 1998;13(S2):S70–S78. [Google Scholar]

- Schweinsburg AD, Schweinsburg BC, Cheung EH, Brown GG, Brown SA, Tapert SF. fMRI response to spatial working memory in adolescents with comorbid marijuana and alcohol use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79(2):201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillington AM, Clapp JD. Substance use problems reported by college students: combined marijuana and alcohol use versus alcohol-only use. Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36(5):663–672. doi: 10.1081/ja-100103566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier LA, Emans SJ, Woods ER, DuRant RH. The association of sexual risk behaviors and problem drug behaviors in high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;20(5):377–383. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Maisto S, Sobell M, Cooper A. Reliability of alcohol abusers’ self-reports of drinking behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1979;17(2):157–160. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell M. Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Allen L, editor. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. New York: The Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Solowij N, Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Babor T, Kadden R, Miller M, et al. Cognitive functioning of long-term heavy cannabis users seeking treatment. JAMA. 2002;287(9):1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Hagerty CE, Herman DS, Phipps MG, Anderson BJ. A brief marijuana intervention for non-treatment-seeking young adult women. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2011;40(2):189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Curtin L. Comparison of extended versus brief treatments for marijuana use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(5):898–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Fearer SA, Williams C, Burke RS. The Marijuana Check-up: promoting change in ambivalent marijuana users. Addiction. 2007;102(6):947–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Fearer SA, Williams C, Picciano JF, Burke RS. The Marijuana Check-up: reaching users who are ambivalent about change. Addiction. 2004;99(10):1323–1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Simpson EE. Treating adult marijuana dependence: a test of the relapse prevention model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(1):92–99. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dawson DA, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Saha T. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80(1):105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The NSDUH Report: Concurrent Illicit Drug and Alcohol Use. Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D, Fergusson D, Milne B, Horwood L, Moffitt T, Sears M, et al. A longitudinal study of the effects of tobacco and cannabis exposure on lung function in young adults. Addiction. 2002;97(8):1055–1061. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden N, Earleywine M. How high: quantity as a predictor of cannabis-related problems. Harm Reduction Journal. 2008;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Jr, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM, Johnston LD. Gender and ethnic differences in smoking, drinking and illicit drug use among American 8th, 10th and 12th grade students, 1976–2000. Addiction. 2003;98(2):225–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner MD, Sussman S, McCuller WJ, Lichtman K. Factors in marijuana cessation among high-risk youth. Journal of Drug Education. 1999;29(4):337–357. doi: 10.2190/PN5U-N5XB-F0VB-R2V1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolard R, Nirenberg TD, Becker B, Longabaugh R, Minugh PA, Gogineni A, et al. Marijuana use and prior injury among injured problem drinkers. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(1):43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]