Abstract

Although schools have been trying to address bulling by utilizing different approaches that stop or reduce the incidence of bullying, little remains known about what specific intervention strategies are most successful in reducing bullying in the school setting. Using the social-ecological framework, this paper examines school-based disciplinary interventions often used to deliver consequences to deter the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors among school-aged children. Data for this study are drawn from the School-Wide Information System (SWIS) with the final analytic sample consisting of 1,221 students in grades K – 12 who received an office disciplinary referral for bullying during the first semester. Using Kaplan-Meier Failure Functions and Multi-level discrete time hazard models, determinants of the probability of a student receiving a second referral over time were examined. Of the seven interventions tested, only Parent-Teacher Conference (AOR=0.65, p<.01) and Loss of Privileges (AOR=0.71, p<.10) were significant in reducing the rate of the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors. By using a social-ecological framework, schools can develop strategies that deter the reoccurrence of bullying by identifying key factors that enhance a sense of connection between the students’ mesosystems as well as utilizing disciplinary strategies that take into consideration student’s microsystem roles.

Keywords: Bullying, Interventions, Schools, Social-ecological framework, Multi-level discrete time hazard models

Introduction

School bullying is a dangerous and persistent problem in the United States and worldwide, but only in the last several decades has it received attention from researchers and practitioners due in part to its increasing viciousness and frequency (Bauman et al. 2008; Chase 2001; Luk et al. 2010; Olweus and Limber 2010; Ross and Horner 2009; Ryan and Smith 2009; Smith et al. 2004) and the introduction of new forms of bullying, such as “cyberbullying” (Li 2006). Bullying is conceptualized as aggressive behavior and characterized by an imbalance of power (Pellegrini and Long 2002) and is believed to be the most common form of violence suffered by children (Ross and Horner 2009). Bullying occurs mostly in schools, in the presence of peers, and is most prevalent during middle school, decreasing in high school (Jensen and Dieterich 2007; Monks et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2004). Although schools in the United States have been trying to stop or reduce the incidence of bullying using a variety of approaches, little remains known about what specific disciplinary strategies are most effective in reducing bullying in the school setting (Hong 2009). Drawing from a social-ecological framework, this paper examines specific school-based disciplinary strategies used with students who have engaged in bullying and how these strategies are associated with deterring the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors among school-aged children.

Background

Although there is no general consensus in defining bullying, there is agreement on its key characteristics: repetitive, unprovoked and intentional physical, verbal, or psychological aggression towards an individual with less power (Farrington and Ttofi 2009; Monks et al. 2009; Pellegrini and Long 2002; Ross and Horner 2009; Smith 2004). The imbalance of power is a key component of bullying behavior (Jensen and Dieterich 2007; Olweus and Limber 2010; Smith et al. 2004), which can include physical fighting, stealing, name calling, teasing, giving “dirty” looks, and spreading rumors (Tarshis and Huffman 2007).

In addition to the direct consequences bullying has for the victim, the breadth of the impact of bullying goes well beyond the bullied. Victims of bullying may suffer both short- and long-term consequences, including depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, suicidal thoughts and stress that interfere with learning (Jensen and Dieterich 2007; Rigby 2007). There is also a link between bullying and later difficulties with substance use, violence, and antisocial behavior (Hong 2009; Jensen and Dieterich 2007; Kaltiala-Heino et al. 2000). A number of studies indicate increased risk of suicidal ideation, low self-esteem and depression for the bullies as well (Hong 2009; Jensen and Dieterich 2007; Luk et al. 2010; Kaltiala-Heino et al. 1999; Monks et al. 2009). Individual bullying behaviors can lead to larger social and economic issues that impact families and communities. Chronic bullying can lead to an increased need for emergency health services, decreased perceived safety and prosocial behaviors in a community, and a negative impact on the economy as a result of children not achieving their full potential and not fully developing healthy social attitudes and behaviors (Cowie and Jennifer 2008).

Efforts to Reduce Bullying in Schools

As a result of growing concern, a number of schools have implemented anti-bullying programs to prevent and reduce the incidence and re-occurrence of bullying in schools (Bauman et al. 2008; Jensen and Dieterich 2007; Monks et al. 2009; Olweus and Limber 2010). The main objective of these programs is to prevent bullying; however, schools must also establish disciplinary standards to address bullying behaviors should they occur. In doing so, many schools subscribe to two overarching approaches when bullying behaviors are reported: (1) a problem solving approach in which peer mediation and counseling are used to focus less on blame and/or punishment and more on positive peer interactions and environmental factors; and (2) a rules and sanctions approach in which school officials institute administrative policies and procedures ranging from “zero-tolerance” policies to a clear outline of punishments for bullies (Cowie and Hutson 2005; Howe et al. 2006). While research evaluating the effectiveness of these anti-bullying interventions is extensive, findings are mixed (Farrington and Ttofi 2009; Jensen and Dieterich 2007; Olweus and Limber 2010; Ryan and Smith 2009). In Ttofi and Farrington’s (2011) systematic review of school-based anti-bullying program effectiveness, only one randomized experiment and five intervention-control designs were significant in reducing bullying, leaving 17 school-based anti-bullying programs ineffective in reducing bullying or aggression.

Studies examining the impact of the rules and sanctions approach show that in some cases bullying continued, with no empirical evidence indicating that zero-tolerance policies reduce bullying or improve school safety (Skiba 2000; Smith et al. 2004; Sugai and Horner 2002). However, anti-bullying programs that follow firm disciplinary sanctions have been shown to be effective in reducing bullying (Ttofi and Farrington 2011). The key to this success is ensuring the school staff consistently implements and enforces the rules and sanctions in place. There is little impact on reducing future bullying or violent behaviors if the rules and sanctions are not consistently enforced (Biggs et al. 2008). In addition to the establishment of clear and consistent rules and disciplinary standards for students in reducing the incidence of bullying (Fekkes et al. 2005; Olweus 1993), findings from Ttofi and Farrington’s (2011) systematic review of anti-bullying programs indicate parental contact (parent meetings and trainings, p<0.0001, information for parents, p<0.013, and school conferences, p<0.08), were important components in successful anti-bullying programs and were associated with a reduction in school-based bullying, emphasizing the need for parental involvement in addition to having clear and consistent rules and disciplinary standards for students.

Social-Ecological Framework

The use of the social-ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner 1979) has been applied to understand the characteristics of bullies and the consequences of bullying (Espelage and Swearer 2003; Swearer and Doll 2001; Swearer et al. 2010) but can also provide a framework for understanding how and why bullying interventions work. The use of an ecological approach to concurrently examine the various systems of students’ lives can provide a holistic understanding of successfully bullying interventions (Song and Stoiber 2008; Swearer et al. 2010). The social-ecological theory posits that students exist and interact within a complex ecological system, consisting of three interrelated systems: the microsystem, the mesosystem, and the macrosystem. The microsystem includes those settings in which the student participates directly (e.g., peers, home, school). Meso-systems represent relationships between those microsystems which indirectly influence students (e.g., parental involvement in education), whereas macrosystems consist of broader social forces and structures that influence students (e.g., school or state-wide policies) (Szapocznik and Coats-worth 1999). These systems can influence, establish, maintain, and impact children’s behaviors, including developing prosocial behavior while inhibiting antisocial behavior (Farmer 2000; Lee 2010; Swearer and Doll 2001; Swearer et al. 2010). Under the social-ecological framework, not only do children who bully have individual characteristics predisposing them to bully, such as being aggressive (Olweus 1997a), unempathetic (Olweus 1997b), or inflexible (Scholte 1992), but peers, families, teachers, and schools also contribute to bullying behaviors and environments. For example, having peers with a low tolerance to dissimilarity among classmates increases the probability of a student bullying (Coloroso 2003; Young and Sweeting 2004); the lack of parental involvement in a child’s life has been linked to aggressive behavior (Olweus 1997b); and teachers can enable bullying behavior by exhibiting insensitivity or indifference to reports of bullying (Craig et al. 2000).

Because “all of the ecological systems significantly influenced bullying behaviors in either direct or indirect ways” (Lee 2010, p. 1688), interventions should too (Leff 2007). Researchers have suggested that anti-bullying interventions should encompass individual solutions, such as teaching problem solving, as well as solutions involving peers, parents, teachers and the school (Hanish and Guerra 2000; Leff 2007; Mishna et al. 2006); however to our knowledge, no research has employed a social-ecological framework to examine bullying interventions as it relates to disciplinary strategies used by schools.

Purpose of Current Study

With most bullying incidents occurring in schools, and children spending the majority of the day at school, it is appropriate to examine the disciplinary strategies school officials and teachers use that deter the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors among school-aged children. This study employs the social-ecological framework to examine how different types of disciplinary strategies-strategies impacting the individual student, strategies inhibiting school privileges, and strategies incorporating parents - deter bullying and aggressive behavior. It is hypothesized that not all disciplinary strategies will be equally successful in addressing bullying. Instead, disciplinary strategies which incorporate the interrelated systems of students’ lives will prove more effective in decreasing the likelihood of a student having a repeat occurrence of bullying and aggressive behavior. More specifically, we hypothesize that:

H1: Disciplinary strategies that impact the student by removing the student from required structure of the school environment, like the classroom, (detention, in-school suspension, out of school suspension, and spending time in the office) will not be effective disciplinary strategies for deterring the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors.

H2: Disciplinary strategies that inhibit or reduce privileged interactions with peers outside the classroom (loss of privileges) will be effective in deterring the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors.

H3: Disciplinary strategies that involve the parents, teachers, and/or administrators (contacting the parent and having a parent-teacher conference) will be effective in deterring the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors.

Method

Data

Data for this study include individual-level information drawn from the School-Wide Information System (SWIS) surveys and school-level information gathered from the National Center on Education Statistics (NCES 2010). Data were obtained through the Education and Community Supports research surveys unit within the College of Education at the University of Oregon. SWIS includes office disciplinary referral data that schools enter through a web-based application. Schools use these data to record, track, and make decisions at student and school levels about behavior support (May et al. 2003). Schools entering data into the SWIS web-based application agree to use a standardized office disciplinary referral form. This includes the adoption of consistent categories and definitions of problem behaviors in which students can engage. These problem behaviors range from minor behaviors (e.g., being tardy to class or having a dress code violation) to major behavior (e.g., possession of drugs or bullying). The office disciplinary referral form contains information that includes time and location of the problem behavior, demographic information on the student, motivating factors for the problem behavior (e.g., obtain peer attention or avoid work), and the disciplinary action taken (e.g., loss of privileges or expulsion). Schools that are included in the data are those that consistently submitted SWIS data over the 3-year time period and that agreed to share their SWIS data for research purposes (Spaulding and Frank 2009).

The dataset used for this study was developed by University of Oregon researchers and made available for use by the Society for Prevention Research (SPR) teams during the 2010 Sloboda & Bukoski SPR Cup competition, and The Institutional Review Board at Arizona State University granted an exemption to this study (Protocol Number: 1004005038). The data represent 61,947 students who received a total of 343,231 office disciplinary referrals during a 3-year period, 2005–06 through 2007–08. The most frequent office disciplinary referrals received were “defiance/disrespect/insubordination/non-compliance” (28.87%), followed by “fighting/physical aggression” (11.94%), “disruption” (6.68%), “minor disruption” (6.29%), and “tardiness” (6.00%). In total there were 11,950 office disciplinary referrals received for bullying, representing 3.48% of the total number of referrals received. The SWIS data came from 166 schools in 65 school districts in 7 states. These schools represented public schools and included students from kindergarten to 12th grade, but the de-indentified data limited the identification of districts or states from which these data were drawn.

Sample

Because the current study is focused on bullying, only students receiving an office disciplinary referral for bullying during the first semester of the respective school year (2005–06, 2006–07, or 2007–08) were included in the sample. In cases where a student received an office disciplinary referral for bullying in more than one school year (less than 3% of the subsample), the first school year was selected for the purposes of the analysis; however, these students were not statistically different on demographic covariates or in the interventions they received compared to students who only received an office disciplinary referral for bullying in only one school year. The final analytic sample included 1,221 students from 122 schools who received an office disciplinary referral for bullying during the first semester. Due to the lower number of students and schools in the final analytic sample, we ran a post-hoc power analysis and found that because of the low rate of repeat bullying combined with the uneven clustering in the data, we had very little power (ESS=397.70) to detect effects at p<.05; thus, our results are analyzed at p<.10 (Killip et al. 2004). (See Appendix A for the calculations of the effective sample size).

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is the receipt of a second office disciplinary referral either for a reoccurrence of bullying or aggressive behavior during the school year (August 1–May 31). For the purposes of the paper, the dependent variable will be termed “second referral.” To be at risk for receiving a second referral, the student must have received a first office disciplinary referral for bullying during the first semester of the same school year. Students received a disciplinary referral for bullying if the student delivered “disrespectful messages (verbal or gestural) to another person that includes threats and intimidation, obscene gestures, pictures, or written notes. Disrespectful messages include negative comments based on race, religion, gender, age, and/or national origin; sustained or intense verbal attacks based on ethnic origin, disabilities or other personal matters.” Although not all physical fighting is necessarily bullying (Kevorkian and D’Antona 2008), research suggests a consistently robust relationship between bullying and fighting or other violent behaviors (Nansel et al. 2003), and because bullying relies on an imbalance of power, bullies can use fighting as a direct means of asserting and gaining power (Kevorkian and D’Antona 2008). In addition, bullying can escalate over time and into more maladaptive, self-destructive behavior, such as fighting (Burns et al. 2008; Kevorkian and D’Antona 2008; Nansel et al. 2004). Thus, aggressive behavior is included in the dependent variable to capture this potential escalation from receiving a first disciplinary referral for bullying during the first semester to receiving a second referral for fighting. Students received a disciplinary referral for aggressive behavior if the student “engaged in actions involving serious physical contact where injury may occur (e.g., hitting, punching, hitting with an object, kicking, hair pulling, scratching, etc.).” The disciplinary referrals were recorded on the school day they were received.

The dependent variable is a dichotomous indicator of whether the student received a second referral given that the student received a prior bullying referral: Y=0 if the student did not receive a second referral and Y=1 if the student did receive a second referral. Duration until students received a second referral is number of calendar days between T=0 and T=1:

T=0: 1st referral: Bullying referral occurred during August 1–December 21.

T=1: 2nd referral: Bullying referral or aggressive behavior referral occurred after T=0 and before May 31.

Independent Variables

The focal independent variable in this study is the disciplinary strategy that the school administration used with the student as a result of the first disciplinary referral for bullying and is time-fixed at T=0. For the remainder of this manuscript, it will be referred to as the intervention. Only interventions that had been received by 30 or more students were included in the analysis. Seven interventions were examined: (1) Detention, defined as “consequence for referral results in student spending time in a specified area away from scheduled activities/classes;” (2) In-school suspension, defined as “consequence for referral results in a period of time spent away from scheduled activities/classes during the school day;” (3) Loss of privileges, defined as “consequence for referral results in student being unable to participate in some type of privilege;” (4) Out of school suspension, defined as “consequence for referral results in a 1–3 day period when student is not allowed on campus;” (5) Parent contact, defined as “consequence for referral results in parent communication by phone, email, or person-to-person about the problem;” (6) Parent-teacher conference, defined as “consequence for referral results in student meeting with administrator, teacher, and/or parent (in any combination);” and (7) Time in office, defined as “consequence for referral results in student spending time in the office away from scheduled activities/classes.” All seven interventions were dichotomized into (0) was not received as the student’s intervention and (1) was received as the student’s intervention.

Individual-level control variables include race/ethnicity, gender, student IEP status, grade of the student, and school year and are all time-fixed at T=0. Race/ethnicity is included as a control variable because racial/ethnic minorities, specifically African Americans, are more likely to be viewed as bullies and report less victimization than other racial/ethnic groups (Juvonen et al. 2003; Nansel et al. 2001; Spriggs et al. 2008). Race/ethnicity includes students who were African American, Latino, and White, with White as the reference group. Students missing on race/ethnicity (42.21%) and students in racial/ethnic categories too small to analyze (2.34%) are excluded from the analysis; however, when these students were included in previous analyses, results did not differ and because of this, our findings represent more conservative models. Gender is included in the model to account for the gendered effect of bullying – females experience indirect bullying, and males experience physical bullying (Jeffrey et al. 2001; Swearer et al. 2010) – and is coded as (0) male and (1) female. Grade of the student is a continuous measure and ranges from (0) kindergarten to (12) 12th grade to account for the differential rates of bullying by age (Jensen and Dieterich 2007; Monks et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2004). Because schools are using these SWIS data to make student- and school-level behavioral support decisions over the 3-year period, school year is included to control for this. School year, a continuous measure of the year in which the referral and intervention were received, is coded as (1) 2005–2006, (2) 2006–2007, (3) 2007–2008.

Hazard Variables

The baseline hazard reflects the average hazard of receiving a second referral on any given day (Barber et al. 2000). The hazard assesses on what day the second referral was received with a higher hazard representing a greater risk of receiving a second referral (Singer and Willett 1993). The baseline hazard model of receiving a second referral is linear; therefore time, the number of days since the first bullying referral was received to the receipt of the second referral, is included to appropriately model the hazard (Barber et al. 2000).

Statistical Analysis: Multi-level Discrete Time Hazard Models

In this article, we employ a multi-level discrete time-hazard model to analyze the determinants of students’ receiving a second referral. First, multi-level analysis is utilized because these data are clustered by school, which is the more appropriate statistical technique when the data are hierarchically clustered (Gupta and da Costa Leite 1999). We model the random effects at the school level because students in the same school have a higher probability of looking more alike than students in different schools (Gupta and da Costa Leite 1999). Second, discrete time hazard models are employed to estimate the probability of a student receiving a second referral over time. The analysis uses a person-period data set (Reardon et al. 2002), in which the period is measured in discrete intervals, in our case days, and the person has multiple records corresponding to each period (Reardon et al. 2002; Singer and Willett 1993). Beginning on the day the student becomes at risk, (i.e., receives a first referral for bullying), the dependent variable, receiving a second referral, is coded as 0 until the day when the student receives a second referral, when it then is coded as 1. After that day, the student no longer contributes person days (Gupta and da Costa Leite 1999). For example, if student X has 25 days between receiving the first disciplinary referral and receiving the second disciplinary referral, student X will have 25 records which correspond to each person day contributed. If student Y has 175 days between referrals, student Y will have 175 records. Because time is in discrete days, the dependent variable is the log odds of a student receiving a second referral on a particular day, conditional upon students receiving a prior bullying referral during the first semester of the school year. Those students who do not receive a second referral contribute person days until they are censored at the end of the school year (May 31), when data collection ended (Singer and Willett 1993). Stata 10 was used for the analyses because of its ability to run multilevel discrete time hazard models (StataCorp 2009).

Thus, for each jth student in school i on day k, the estimated log odds of a second referral is:

where β0 (the intercept) measures the between-school average baseline log odds of receiving a second referral for the reference student at time 0, β1 estimates the effect of loss of privileges, β2 estimates the effect of parent-teacher conferences, β3 estimates the effect of being an African American, β4 estimates the effect of being Latino, β5 estimates the effect of being female, β6 estimates the linear effect of the student’s grade, β7 estimates the linear effect of the school year, and β8 estimates the effect of days. In this model, uij represents the difference between each school’s estimated intercept (baseline hazard) and the between-school average. Since we postulate that each school has its own baseline hazard, our model estimates the standard deviation of the school intercepts as the estimated standard deviation of uij. The magnitude of this random effect offers insights as to the between-school variability of our hazard models.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 illustrates the demographic characteristics of students who received a bullying disciplinary referral during the first semester (T=0) and students who received a second referral (T=1). The majority of students at both T=0 and T= 1 were in grades 4 through 8 (70.77% and 73.16%, respectively). The sample was predominantly male with a large percentage at both T=0 (72.32%) and T=1 (79.40%). The sample was fairly well distributed between the three ethnic groups: African American, Latino, and White. The majority of first bullying incidents took place in the classroom (34.23%), on the playground (16.22%), or in the hallway (13.19%) (data not shown). Disciplinary strategies in response to the bullying at T=0 included 8.03% of the students receiving a loss of privileges, 13.43% receiving a parent-teacher conference, 7.29% received parent contact, and the remaining 71.25% receiving some other intervention. Less than half (43.33%) of the sample received a second referral. Of those that did, 38% were for bullying and 62% were for aggressive behavior (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of student characteristics at receipt of first bullying referral and at receipt of second referral

| Time 0 Sample of students with first bullying referral (N=1,221) |

Time 1 Sample of students with second referral (N=529) |

|

|---|---|---|

| % | % | |

| African American | 25.55 | 31.38 |

| Latino | 29.89 | 30.06 |

| White | 44.55 | 38.56 |

| Male | 72.32 | 79.40 |

| In grades 4–8 | 70.77 | 73.16 |

| Received Loss of Privileges | 8.03 | – |

| Received Parent-Teacher Conference | 13.43 | – |

| Received Parent Contact | 7.29 | – |

| Received Another Type of Intervention | 71.25 | – |

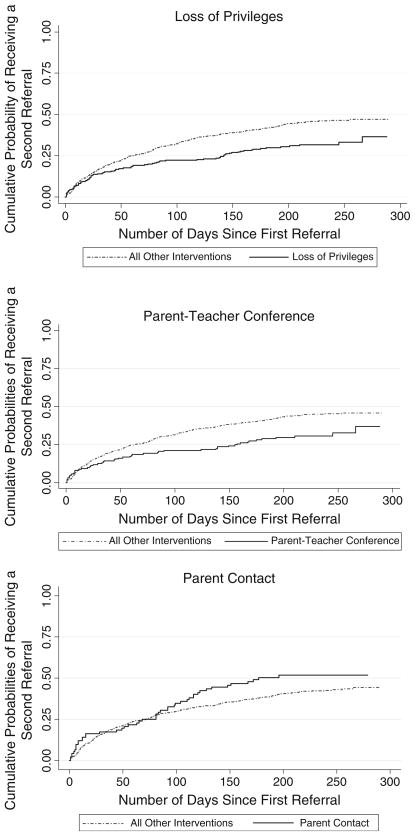

Kaplan-Meier Failure Function

Kaplan-Meier Failure Functions were used to estimate the cumulative probability of receiving a second referral for each day in the data. The Kaplan-Meier Failure Function allows the comparison of cumulative probability of failure between groups. In this case, we analyzed each intervention separately against all other interventions, and using the log-rank test, assessed if each intervention was significantly different than all other interventions in receiving a second referral over time. Of the seven interventions, only loss of privileges (χ2=12.66, p<0.01), parent contact (χ2=3.07, p=0.08), and parent-teacher conference (χ2=8.60, p<0.05) were significantly different than all other interventions; however, only loss of privileges and parent-teacher conference were significant in reducing the cumulative probability of receiving a second referral over time. As Fig. 1 shows, students who received loss of privileges or parent-teacher conference had a significantly lower probability of receiving a second referral than students receiving any other type of intervention, while students receiving parent contact had a significantly higher probability of receiving a second referral. Detention (χ2=0.001, p=0.99), in-school suspension (χ2=1.98, p=0.16), out-of-school suspensions (χ2=1.01, p=0.32) and time in office (χ2=0.03, p=0.86) were not significantly different than all other interventions in reducing the cumulative probability of receiving a second referral over time. Because the focus of this paper is to examine interventions that deter the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors, only loss of privileges and parent-teacher conference were examined in further detail in the multi-level discrete time hazard models.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier failure estimates for loss of privileges, parent-teacher conference, and parent contact

Multi-Level Discrete Time Hazard Model

In the multi-level discrete time hazard models, the coefficients are presented as odds ratios; “when there are many time periods of risk relative to the number of events, however, the odds approximate the rates” (Yabiku 2005, p. 345). Therefore, the coefficients are interpreted and discussed as rates of receiving a second referral. After adjustment for individual-level demographic covariates and school-level random effects, students whose intervention was loss of privileges received a second referral at rates 29% lower than students who received another type of intervention (AOR= 0.71, p<.10) (Table 2). Similarly, compared to another type of intervention, students whose intervention was a parent-teacher conference received a second referral at rates 35% lower (AOR=0.65, p<.01). Compared to Whites, African American students have significantly higher rates of receiving a second referral (AOR=1.77, p<.001); however, Latino students were not significantly different than Whites in second referral rates. In addition, females (AOR=0.63, p<.001) received a second referral at significantly lower rates than their male counterparts. While the school year the referral was received was significant (AOR=0.90, p<.10), grade of the student was not significant in predicting rates of receiving a second referral.

Table 2.

Results of multi-level discrete time hazard model predicting the probability of receiving a second referral

| β (SE) | AOR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | |||

| Loss of Privileges | −0.35 (0.21) | 0.71* | (0.47–1.06) |

| Parent-Teacher Conference | −0.43 (0.16) | 0.65*** | (0.48–0.88) |

| Race/Ethnicitya | |||

| African American | 0.57 (0.12) | 1.77**** | (1.39–2.25) |

| Latino | 0.15 (0.12) | 1.16 | (0.91–1.48) |

| Genderb | −0.47 (0.11) | 0.63**** | (0.50–0.78) |

| Grade of Student | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.99 | (0.95–1.05) |

| School Year | −0.11 (0.06) | 0.90** | (0.80–1.01) |

| Time | −0.01 (0.001) | 0.99**** | (0.99–0.99) |

| Intercept | −5.07 (0.21) | ||

| Random Effects | |||

| Intercept | 0.42 (.08) | ||

| Intraclass Correlation | .05 | ||

| Loglikelihood | −3332.51 | ||

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

N=1,221 respondents and 184,062 person days

Reference group for race/ethnicity is White

Reference group for gender is male

Reference group for student IEP status is no IEP

To understand the meaning of the random effect, we must first consider the meaning of the intercept. The intercept was measured as −5.07, which translates into a baseline probability of a second referral the next day of about 0.6%. If the standard deviation of the intercept is estimated to be 0.42, then it is plausible that 95% of the schools have intercepts that range between −5.91 (0.3% chance) and −4.23 (a 1.4% chance). While this is not a substantively large range, it does illustrate that there is a measureable range to the school’s baseline hazards.

Discussion

A social-ecological framework is a useful approach for understanding bullying interventions. Swearer et al. (2010) posit that a failure to direct the attention of current anti-bullying programs at the social-ecology of the student, including his/her peers and families, is one reason for limited effectiveness across settings. Schools can serve as both a microsystem and a mesosystem for students. In the microsystem, school serves as a community in which students participate directly and interact with others. At the mesosystem, the school serves to bring together microsystems such as peer groups, families, and neighborhood influences (Coatsworth et al. 2002). These findings provide support that effective bullying interventions should incorporate the multiple systems of children’s lives, which is particularly important given the repetitive nature of bullying (Farrington and Ttofi 2009; Monks et al. 2009; Pellegrini and Long 2002; Ross and Horner 2009; Smith 2004). As suggested in this study’s findings, interactions between the student, his/her peers, and family within the school context appear to be key elements of the disciplinary strategies identified as significantly deterring repeat offenses – loss of privileges and parent-teacher conference.

Our first hypothesis was supported. Disciplinary strategies that only impact the student by removing the student from the classroom and school environment (detention, in-school suspension, out of school suspension, and spending time in the office) were not effective in deterring the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors. It appears, drawing from the social-ecological framework, anti-bullying interventions that do not encompass or incorporate peers, parents, teachers or the school (Hanish and Guerra 2000; Leff 2007; Mishna et al. 2006), are not effective in deterring repeat offenses of bullying or aggressive behaviors. It appears that removal from the classroom and school environment could be perceived as a positive consequence for a child who does not function well or feels inadequate in the school environment. While future research should investigate the mechanisms that make removal from the classroom and school environment less effective in deterring the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors, this finding helps illustrate a clear distinction between disciplinary strategies that remove the student from classroom or from campus altogether, versus those that involve the micro and mesosystems, like loss of privileges and parent-teacher conference.

Two interventions, however, were found to be significant. The first intervention– loss of privileges – supports our second hypothesis that disciplinary strategies that inhibit privileges and interaction with peers outside the classroom will be significant in deterring the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors. This finding suggests that influences at the microsystem can have a direct impact on reducing rates of bullying and aggressive behavior. A loss of privileges can take away a child’s special or earned rights as a member of the school community or peer environment, thus directly impacting their participation and interaction within this microsystem. In this sense, children who lost privileges cannot function and interact with their peers in privileged places such as the playground. While a clear limitation of this data is that “privilege” is not clearly defined and therefore inconsistently applied, its significance in deterring repeat offenses of bullying and aggressive behavior suggests that further exploration of peer interactions in privileged places is warranted.

Parent-teacher conference was also significant in deterring repeat offenses of bullying and aggressive behavior, partially supporting our third hypothesis that disciplinary strategies that involve the parents, teachers, and/or administrators (contacting the parent and having a parent-teacher conference) will be significant in deterring the reoccurrence of bullying and aggressive behaviors. It has been suggested that parent involvement may be key to successful bullying interventions (Ttofi and Farrington 2011) because it creates an impact at the child’s mesosystem by creating interaction between the two environments that tend to have the primary influence on the lives of children – home and school (Epstein 1995; Grolnick and Ryan 1989; Sheldon and Epstein 2002). However, our findings indicate that type of parental engagement matters in the success of parents in influencing bullying behavior. While parent-teacher conference was significant in deterring repeat offenses of bullying and aggressive behavior, parent contact significantly increased the likelihood of a repeat offense. Given that parents can actually contribute to bullying behavior through modeling and tolerance (Swearer and Doll 2001) and that parents may define the term “bullying” or interpret its significance very differently from the child or the school (Mishna et al. 2006), it is not surprising that the form of parental contact or engagement may result in very different outcomes. These data do not include information about the parent-child relationship, parent-school involvement, or other potential key mechanisms in the child-parent-school system and should be further examined. However, understanding that type of parental engagement matters in long-term bullying prevention intervention is an important contribution of this study.

Through a social-ecological lens, bullying as a social problem cannot be addressed by looking at the child and his/her environment as separate entities. Rather, the ongoing interactions between the two systems must be understood in order to adequately address the problem at hand (Swearer and Doll 2001). An effective anti-bullying intervention should take the dynamic nature of child and social contexts into consideration. Similarly, an effective evaluation of existing interventions should do the same. The SWIS data offer a great deal of potential for exploring bullying interventions using a unique outcome measure (office referral) over time. However, what is not known from these data includes the relationship between the students, peers, teachers, administration and parents prior to the disciplinary intervention, as well as the relationship building that may occur as a result of the intervention. In the dynamic, ecological context, the nature of these relationships would improve our understanding the findings. These additional factors would allow for more targeted efforts to deter repeat offenses of bullying and aggressive behavior through consistent implementation and enforcement of rules and sanctions. Given that in the existing sample approximately 21% received either loss of privileges or parent-teacher contact at the first bullying offense, empirical evidence of the effect of select disciplinary strategies in reducing the odds of repeat offenses over time may be of value for schools. Because bullying behavior is influenced by a student’s complex ecological system so too should the interventions (Leff 2007).

Limitations

Because these data were drawn from 166 schools from 7 states, the first day of school and the last day of school were unknown and may not be the same. In order to estimate the multi-level discrete time hazard model, August 1 and May 31 were selected as the first and last days of school for the entire sample; however, it is possible that some students contributed person days before or after his/her own school year. Future research should include more school-level characteristics to better model bullying behavior over time. This study also relies only on the accuracy of bullying reports and student characteristics from teachers and school personnel; thus, these reports may be of more serious bullying offenses and not the more relational or covert bullying which can also take place in the school environment (Espelage and Swearer 2003). Because of this, some schools may have an under-reported rate of bullying. Although all SWIS schools received a 3-day training (May et al. 2003), it is possible that administrator, teacher, and school climate characteristics influenced the rate of office referrals and the rate of reporting student characteristics, as seen in the underreporting on the race/ethnicity of the student. Future work should ensure that schools are accurately adhering to the agreed upon definition of bullying and that all data are entered in a systematic way. In addition, although this was a 3-year study, when students moved schools, whether students physically moved into a different neighborhood and changed schools or a students graduated from one school and moved into the next school (e.g., elementary to middle), students were unable to be tracked. As such, any longitudinal data surrounding the bullying effectiveness across years is unable to be discerned. Future research should follow these students over time to test the longitudinal effectiveness of bullying interventions.

While there was consensus of the definitions of problem behavior (as noted above), there are no guidelines within the SWIS data as to which interventions should be given for which problem behaviors. Schools and administrators were left to their own discretion as to which intervention to assign and in some cases how the specifics of the intervention would be handled. For example, parent-teacher conference, as defined, could include any combination of the parent, the teacher, and the school administrator with the student. Similarly, with loss of privileges the specific privilege is unknown leaving the interpretation of “privilege” to the subjective discretion of the administrator implementing the disciplinary intervention. The disposition of the intervention is also unknown. Although SWIS indicates that for some interventions, specifically suspensions and expulsions, “the schools are instructed to log the total number of days the student was suspended/expelled from school,” there are no other indicators to determine if the intervention decided upon actually occurred. It is possible that the principal selected parent-teacher conference for those parents who the principal knows will comply or for children who may be in different circumstances. Because these data are observational, this study cannot give a causal interpretation for interventions leading to a reduction in bullying.

In addition, as readers, some definitions of the interventions may appear overlapping - an inherent limitation in this study - however, in these secondary data, the interventions were categorized and implemented in the school setting as mutually distinct interventions. For example, privileges, in regards to loss of privileges, are not a mandatory required component of the school environment, but rather something the student earns and a right that can be taken away. On the other hand, interventions like detention, in-school suspension, or out of school suspensions are meant to exclude students from the regular, required structure of the school (e.g., classroom or lunch) and impose a more firm structure to the school environment, particularly in the case of detention and in-school suspension. While it may be argued that these punishments can also include a loss of privileges, in the context of the original study, interventions were implemented as distinct interventions. Future research should more clearly define and distinctly categorize each intervention. Even with these limitations, these findings do show a significant association between parent-teacher conference, loss of privileges, and a reduction of bullying over time, even controlling for school random effects and those factors which may be suggestive as to characteristics of students and therefore parents who may be more willing to comply. Future research should develop a randomized control trial to further test this association independent of any school-, parent-, or individual-level characteristics that may be associated with these findings.

Implications for Practice and Future Research

Mishna et al.’s (2006) qualitative study of students, parents, and educators identified difficulty for teachers in finding the time and resources necessary to adequately address bullying, in addition to addressing both academic and social needs of students. With this in mind, it is important to consider existing strategies that schools employ to address problem behaviors as part of daily operations, such as the disciplinary strategies identified in the current study. This does not detract from the importance of bullying-specific programs and interventions, but may serve as a compliment to existing anti-bullying efforts. In addition, bullying prevention and intervention in schools may also include parent education sessions related to bullying (e.g., recognizing bullying, learning how to handle bullying), teacher and school personnel training on ways to handle bullying as a team, peer training (e.g., reporting of bullying, handling bullying), and even training for policy makers about bullying and prevention and intervention needs. More research to further explore the implications of the current study will allow for the enhancement of existing and future anti-bullying efforts and an opportunity to consider the factors associated with implementation of a successful rules and sanctions approach beyond those already identified (i.e., consistency and firm methods).

By using a social-ecological framework to understand the influences of peers, parents, and schools, schools can identify strategies that serve to best deter bullying. This study suggests that certain strategies–loss of privileges and parent-teacher conference–may be more successful than others in reducing or stopping bullying incidents through the connection between the child’s ecological systems. By focusing on identification of factors that support successful determent of repetitive bullying behaviors, interventions can be developed that acknowledge the connection between self, peers, family, school, and community. Such interventions could allow schools to incorporate intervention efforts, using the success of existing disciplinary strategies, in ways that prove effective in maintaining a safe environment.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Society for Prevention Research conference (2010, June) in Denver, CO as part of the Sloboda and Bukoski SPR Cup Competition (Eddy & Martinez, 2008). The authors’ time was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD/NIH), award P20 MD002316-04 (F. Marsiglia, P.I.) to the Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center at Arizona State University. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCMHD or the NIH.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Robert H. Horner and Dr. Jennifer Frank of the Education and Community Supports research surveys unit within the College of Education at the University of Oregon for allowing us use of the data.

Appendix A

Effective Sample Size

Because each school did not contribute the same number of students to the study, the harmonic mean was calculated using Stata 9.0 (H=3.7).

ESS Effective Sample Size

m Average number of students who bullied per school based on the harmonic mean (H)

k Number of schools

ρ Intraclass correlation

Contributor Information

Stephanie L. Ayers, Email: stephanie.l.ayers@asu.edu, Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, College of Public Programs, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA. Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, Arizona State University, 411 N. Central Ave, Suite 720, Phoenix, AZ 85004602-496-0700, USA

M. Alex Wagaman, Arizona State University School of Social Work & Health Disparities Doctoral Intern, Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, Phoenix, AZ, USA.

Jennifer Mullins Geiger, Arizona State University School of Social Work & Health Disparities Doctoral Intern, Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, Phoenix, AZ, USA.

Monica Bermudez-Parsai, Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, College of Public Programs, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA.

E. C. Hedberg, Research Scientist, National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

References

- Barber JS, Murphy SA, Axinn WG, Maples J. Discrete-time multilevel hazard analysis. Sociological Methodology. 2000;30:201–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman S, Rigby K, Hoppa K. US teachers and school counselors’ strategies for handling school bullying incidents. Educational Psychology. 2008;28:837–856. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs BK, Vernberg EM, Twemlow SW, Fonagy P, Dille EJ. Adherence and its relation to teacher attitudes and student outcomes in an elementary school-based violence prevention program. School Psychology Review. 2008;37:533–549. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Burns S, Maycock B, Cross D, Brown G. The power of peers: Why some students bully others to conform. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18:1704–1716. doi: 10.1177/1049732308325865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase B. Bullyproofing our schools. 2001 Mar 25; Retrieved July 15th, 2010, from http://www.nea.org/columns/bc010325.html.

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, McBride C, Briones E, Kurtines W, Szapocznik J. Ecodevelopmental correlates of behavior problems in young Hispanic females. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6:126–143. [Google Scholar]

- Coloroso B. The bully, the bullied, and the bystander. New York: Harper-Resource; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie H, Hutson N. Peer support: a strategy to help bystanders challenge school bullying. Pastoral Care in Education. 2005;23:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie H, Jennifer D. New perspectives on bullying. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Craig WM, Pepler D, Atlas R. Observations of bullying in the playground and in the classroom. School Psychology International. 2000;21:22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JL. School/family/community partnerships: Caring for the children we share. Phi Delta Kappan. 1995;76:701–712. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Swearer SM. Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we go from here? School Psychology Review. 2003;32:365–383. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer TW. The social dynamic of aggressive and disruptive behavior in school: Implications for behavior consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation. 2000;11:299–321. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Ttofi MM. How to reduce school bullying. Victims and Offenders. 2009;4:321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Fekkes M, Pijpers FIM, Vereloove-Vanhorick SP. Bullying: Who does what, when and where? Involvement of children, teachers and parents in bullying behavior. Health Education Research. 2005;20:81–91. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS, Ryan RM. Parent styles associated with children’s regulation and competence in schools. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1989;81:143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, da Costa Leite I. Adolescent fertility behavior: Trends and determinants in Northeastern Brazil. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;25:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Guerra NG. Children who get victimized at school: What is known? What can be done? Professional School Counseling. 2000;4:113–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hong JS. Feasibility of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program in low-income schools. Journal of School Violence. 2009;8:81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Howe E, Haymes E, Tenor T. Bullying: Best practices for prevention and intervention in schools. In: Franklin C, Harris MB, Allen-Meares P, editors. The school services source-book: A guide for school-based professionals. Cambridge, MA: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 461–467. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey LR, Miller D, Linn M. Middle school bullying as a context for the development of passive observers to the victimization of others. In: Geffner RA, Loring M, Young C, editors. Bullying behavior: Current issues, research, and interventions. New York: Haworth Press; 2001. pp. 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen JM, Dieterich WA. Effects of a skills-based prevention program on bullying and bully victimization among elementary school children. Prevention Science. 2007;8:285–296. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Graham S, Schuster MA. Bullying among young adolescents: The strong, the weak, and the troubled. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1231–1237. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpela M, Marttunen M, Rimpela A, Rantanen P. Bullying, depression, and suicidal ideation in Finnish adolescents: School survey. British Medical Journal. 1999;319:348–351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7206.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpela M, Rantanen P, Rimpela A. Bullying at school: An indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23:661–674. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevorkian M, D’Antona RD. 101 facts about bullying: What everyone should know. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Killip S, Mahfoud Z, Pearce K. What is an intracluster correlation coefficient? Crucial concepts for primary care researchers. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2004;2:204–208. doi: 10.1370/afm.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. An ecological systems approach to bullying behaviors among middle school students in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;26:1664–1693. doi: 10.1177/0886260510370591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS. Bullying and peer victimization at school: Considerations and future directions. School Psychology Review. 2007;36:406–412. [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. Cyberbullying in schools: A research of gender differences. School Psychology International. 2006;27:157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Luk JW, Wang J, Simons-Morton BG. Bullying victimization and substance use among U.S. adolescents: Mediation by depression. Prevention Science. 2010;11:355–359. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0179-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May S, Ard W, Todd A, Horner RH, Glasgow A, Sugai G, et al. School-wide information system. Eugene: Educational and Community Supports, University of Oregon; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mishna F, Pepler D, Wiener J. Factors associated with perceptions and responses to bullying situations by children, parents, teachers, and principals. Victims and Offenders. 2006;1:255–288. [Google Scholar]

- Monks CP, Smith PK, Naylor P, Barter C, Ireland JL, Coyne I. Bullying in different contexts: Commonalities, differences and the role of theory. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:146–156. [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton BG, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among U. S. youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck MD, Haynie DL, Ruan WJ, Scheidt PC. Relationship between bullying and violence among US youth. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:348–353. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Craig W, Overpeck MD, Saluja G, Ruan WJ the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Bullying Analyses Working Group. Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:730–736. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCES. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences; Washington, DC: 2010. Retrieved on September 13, 2010 from http://nces.ed.gov/about/ [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Tackling peer victimization with a school-based intervention program. In: Fry DP, Bjorkqvist K, editors. Cultural Variation in Conflict Resolution: Alternatives to Violence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1997a. pp. 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bully/victim problems in schools: Knowledge base and an effective intervention program. The Irish Journal of Psychology. 1997b;18:170–190. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D, Limber SP. Bullying in school: Evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:124–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Long JD. A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002;20:259–280. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon SF, Brennan RT, Buka SL. Estimating multilevel discrete-time hazard models using cross-sectional data: Neighborhood effects on the onset of adolescent cigarette use. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2002;37:297–330. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3703_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby K. Bullying in schools: And what to do about it. Camberwell, Australia: ACER Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ross SW, Horner RH. Bully prevention in Positive Behavior Support. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:747–759. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan W, Smith JD. Anti-bullying programs in schools: How effective are evaluation practices? Prevention Science. 2009;10:248–259. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0128-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholte EM. Prevention and treatment of juvenile problem behavior: A proposal for a socio-ecological approach. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1992;20:247–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00916691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon SB, Epstein JL. Improving student behavior and school discipline with family and community involvement. Education and Urban Society. 2002;35:4–26. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. It’s about time: Using discrete-time survival analysis to study duration and the timing of events. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1993;18:155–195. [Google Scholar]

- Skiba RJ. Zero tolerance, zero evidence: An analysis of school disciplinary practice (Publication No. SRS2) Bloomington: Indiana Education Policy Center; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Schneider BH, Smith PK, Ananiadou K. The effectiveness of whole-school antibullying programs: A synthesis of evaluation research. School Psychology Review. 2004;33:547–560. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK. Bullying: Recent developments. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2004;9:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2004.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SY, Stoiber KC. Children exposed to violence at school: An evidence-based intervention agenda for the “real bullying” problem. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2008;8:235–253. [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding SA, Frank JL. Comparison of office discipline referrals in U.S. schools by population densities: Do rates differ according to school location? Eugene: Educational and Community Supports, University of Oregon; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs AL, Iannotti RJ, Nansel TR, Haynie DL. Adolescent bullying involvement and perceived family, peer and school relations: Commonalities and differences across race/ethnicity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;41:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, MD: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sugai G, Horner R. The evolution of discipline practices: School-wide positive behavior supports. Behavior Psychology in the Schools. 2002;24:23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Swearer SM, Doll B. Bullying in schools: An ecological framework. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2001;2:7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Swearer SM, Espelage DL, Vaillancourt T, Hymel S. What can be done about school bullying? Linking research to educational practice. Educational Researcher. 2010;39:38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing the influences on drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In: Glantz M, Hartel CR, editors. Drug abuse: Origins and interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 331–366. [Google Scholar]

- Tarshis TP, Huffman LC. Psychometric properties of the peer interactions in primary school (PIPS) Questionnaire. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28:125–132. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000267562.11329.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, Farrington DP. Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2011;7:27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yabiku ST. The effect of non-family experiences on age of marriage in a setting of rapid social change. Population Studies. 2005;59:339–354. doi: 10.1080/00324720500223393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R, Sweeting H. Adolescent bullying, relationships, psychological well-being, and gender-atypical behavior: A gender diagnosticity approach. Sex Roles. 2004;50:525–534. [Google Scholar]