Abstract

Background:

The chemoprevention of chemically-induced hepatotoxicity is a crucial means of minimizing susceptibility to hepatic carcinogenesis and plants remain a rich source of anti-hepatotoxicants with antioxidant properties.

Objective:

The protective role of defatted-methanol (MECF) and ethyl acetate fractions (EF), obtained from Leaves of Cnestis ferruginea in rats induced with carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) toxicity was investigated.

Materials and Methods:

Adult male Wistar rats were orally administered MECF or EF (125 – 500 mg/kg bwt/5mL) or silymarin (25 mg/kg bwt/5 mL) separately for three days before intervention with an intraperitoneal dose of CCl4. Biomarkers of liver and kidney toxicity as well as Ca2+ regulation were evaluated.

Results:

Pre-treatment with MECF and EF significantly (P < 0.05) decreased the activities of serum alanine and aspartate aminotransferases, levels of urea, creatinine and cholesterol. A significantly (P < 0.05) enhanced Ca2+ -ATPase activity and lowered levels of membrane cholesterol: Phospholipid ratio were observed in liver microsomes of pre-treated as compared to CCl4 -only treated rats. Rat liver superoxide dismutase activity was enhanced by 125 mg/kg and 250 mg/kg of EF and MECF, while decreases were observed at 500 mg/kg. MECF and EF, like silymarin, attenuated CCl4 -induced hepatotoxicity, microsomal membrane Ca2+ -ATPase inactivation and renal dysfunction. Phytochemistry of MECF revealed the presence of anthraquinones, cardiac and flavone glycosides, tannins and trihydroxyl phenol.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that the mechanism of hepatoprotection elicited by MECF and EF, involve its antioxidative properties and regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis.

Keywords: CCl4 -induced hepatotoxicity, Ca2+ -ATPase activity, Cnestis ferruginea, hepatoprotection, renal protection

INTRODUCTION

The liver is actively involved in metabolic functions and also a frequent target of numerous intoxications. The hepatotoxin, CCl4, has been extensively studied as a model compound producing hepatocellular necrosis. CCl4 mediates its hepatotoxicity after biotransformation by hepatic microsomal cyt p450 to generate trichloromethyl free radicals which launch attacks on membrane proteins, thiols and lipids leading to membrane lipid peroxidation and subsequently to necrotic cell death.[1] The early events in rats (30 min-1 h) after oral administration of CCl4 include destruction of lipid metabolism, alteration in appearance of endoplasmic reticulum and microsomal drug-metabolizing enzyme activity, depression of hepatic protein synthesis, 15-20 times upsurge of calcium sequestered by mitochondria and inhibition of microsomal calcium pump.[2] Consequently, it has been suggested that the Ca2+ -ATPase could be used as a target for toxins and drugs.[3]

The chemoprevention by anti-cancer agents and their combinations are frequently being evaluated. Several natural products (herbs and spices), possessing antioxidant properties, fall within this class and were found to protect hepatocytes against chemically-induced liver carcinogenesis.[4] Their mechanisms of chemoprevention include stimulation of the induction of apoptosis in transformed hepatocytes, inhibition or scavenging of ROS which eliminates or lowers the extent of lipid peroxidation or inflammation in liver cells thus; ultimately preventing the incidence of hepatic necrosis.[5] In addition, the antioxidant properties of some of these plants, especially their isolated compounds have found therapeutic benefits in pathological conditions such as liver diseases, cancer, diabetes and heart diseases.[6] Obviously, a greater percentage of these potential antioxidant plants, particularly those with promising hepatoprotective properties are yet to be explored.

The leaves of Cnestis ferruginea D.C. (Connaraceae), a native of Africa, are being used in traditional medicine, as laxative, remedy for dysentery and gonnorhoea. Different parts of the plant have a variety of traditional uses; the fruit juice is widely used for the treatment of skin infections, tooth and mouth aches. The extracts of root, stem and leaves of Cnestis ferruginea possess antibacterial, antifungal and anticonvulsant activities. The root contains compounds such as coumarins, squalene, flavonoid and β-sitosterol while the fruits have afrormosin -7-O beta -D- galactoside.[7] Moreover, the methanol leaf extracts have exhibited anti-glycating property in vitro and hypoglycaemic activity in vivo in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats.[8,9] Recently, two phenolic compounds - para-hydroxyphenol and robustaside B were isolated for the first time from the ethyl acetate fraction of the leaves of Cnestis ferruginea and shown to possess antioxidant property.[10] Considering the critical role of the liver in detoxification of xenobiotics, and cellular metabolism plus the consequences of a diseased liver, the search for hepato-protective agents through plant products with antioxidant properties is on the increase. Hence, it is envisaged that the antioxidant compounds in the leaves of Cnestis ferruginea may offer protection to the liver against CCl4 -induced free radical mediated toxicity. Presently, there is paucity of information on the hepatoprotective activity of Cnestis ferruginea and modulatory effects of potent medicinal plants on cytoplasmic calcium homeostasis, involving the hepatic microsomal membrane Ca2+ -ATPase. Thus, this study was designed to assess and compare the hepato-protective capacity of the antioxidant-rich methanol extracts and partially purified ethyl acetate fractions of leaves of Cnestis ferruginea in CCl4 –induced toxicity. Furthermore, the protective potential of the extracts against CCl4 -induced modulation of liver microsomal membrane Ca2 + ATPase activity in rats was also investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

CCl4, bovine serum albumin (BSA), potassium chloride (KCl), sucrose, n-hexane, methanol, ethyl acetate, chloroform, adenine nucleotide triphosphate (ATP), ethylene- glycol tetra acetic acid (EGTA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Silymarin was purchased from ‘The Abbot Laboratories’. Alanine amino transferase (ALT), aspartate amino transferase (AST), creatinine, urea and cholesterol kits were obtained from Diasys Diagnostic Systems (Istanbul, Turkey). All other reagents used were of analytical grade.

Preparation and qualitative determination of phytochemicals in leaf extracts of Cnestis ferruginea

Fresh leaves of Cnestis ferruginea were collected from the Forestry Research Institute of Nigeria (FRIN) Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. The samples were authenticated and identified by Mr T. K. Odewo, at the Herbarium of the Institute, where specimen (Voucher No. 106524) had earlier been deposited. The dried powdered and pre-weighed leaves were de-fatted with n-hexane (100%) and re-extracted with methanol (95%v/v) in soxhlet apparatus at 60ΊC for 12 h. The methanol extract obtained was re-extracted in succession with chloroform (100%) and ethyl acetate (100%). Methanol and ethyl acetate extracts were concentrated in a rotary evaporator at 40ΊC. Methanol extracts residue of Cnestis ferruginea (MECF) and its ethylacetate fractions (EF) were screened for the presence of alkaloids, cardenolides, saponins and anthraquinone glycosides using standard pharmacognosis methods described by Trease and Evans.[11] MECF and EF were separated on a thin layer chromatographic plate (Reverse phase18F254s, Merck KGa A; 64271, Darmstadt, Germany) in a solvent system (methanol: water. 60: 40). The chromatograms of the extracts were screened for their chemical constituents and radical scavenging property by spraying with 1, 1 diphenyl 2-picryl hydrazine (DPPH) radical solution (1mg/mL), ferric chloride and aluminium chloride solutions.

Maintenance of animals

Male Wistar strain albino rats (180 -200gm, 16 weeks old) were bred and housed at the animal house of H.E.J. Research Institute of Chemistry, University of Karachi, Karachi, under a 12h light/dark condition. The experimental design was approved by the Animal Care Ethics Committee (ACEC) of H.E.J. Research Institute of Chemistry, University of Karachi, Karachi and the protocols conformed to the guidlines of the National Institute of Health (NIH). Animals had free access to food (rat chow) and water throughout the experimental period.

Experimental design

Forty five male Wistar strain albino rats fasted overnight were divided into 9 groups of five animals per group. Group A received 1.5 mL/kg body weight (b.w.) of olive oil plus 5 mL/kg b.w. of 1% carboxylmethyl cellulose (CMC), group B received 1.5 mL/kg of 20% CCl4 in olive oil, groups C, D and E received 125, 250 and 500 mg/kg b.w./5 mL of MECF, respectively. Furthermore, groups F, G and H received 125, 250 and 500 mg/kg b.w./5 mL of MECF only respectively, while group I received 25 mg/kg b.w./5 mL of silymarin. In another experiment of the same design, using a different set of 45 animals, MECF was replaced with EF. All extracts were administered through oral cannulation for three days. On the 3rd day, animals in groups B, C, D, E and I were challenged with 1.5 mL/kg of 20% CCl4 in olive oil exactly 3h after administration of the last dose of MECF, EF or silymarin. All animals were anaesthesized with sodium pentothal (i.p, 60 mg/kg) and sacrificed 24h after the CCl4 intoxication.

Sample collection and preparation

Blood sample collected from the carotid artery was allowed to coagulate for 30 min and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min to separate the serum. Livers were quickly excised, trimmed, rinsed with 1.15% ice cold KCl, blotted and weighed. Livers were suspended in ice-cold 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 5% suspension) and homogenized in a polytron homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 m for 20 min and the supernatant (post mitochondrial fraction) obtained was centrifuged at 105,000 m for 1h in a cold ultra centrifuge (L-8-70M, Beckman, USA). The microsomes were suspended in ice-cold 0.25 M sucrose or homogenizing buffer (20mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, 210 mM Mannitol, 70mM Sucrose, pH 7.4).

Analysis of biochemical parameters in serum, liver homogenate and microsomal fraction,

Liver function was assessed by measuring the serum alanine amino transferase (ALT) and aspartate amino transferase (AST) activities using the Diasys kit as described by Bergmeyer et al.[12] Kidney function was assessed by measuring the levels of serum creatinine and urea.[13] Cholesterol concentrations in rat liver microsomal fraction and sera were measured as described by Rifai et al.[14] Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was assayed by monitoring the inhibition of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction as described by Marklund.[15] using a commercially available SOD assay kit purchased from Cayman Chemical, Ann Abor, MI). Data were expressed as SOD units/mg as compared to the standard.

Biochemical assessment of microsomal membrane integrity

Measurements of microsomal membrane proteins, cholesterol and phospholipid contents were used to evaluate the extent to which the microsomal membranes were preserved. Total protein concentration of the microsomes was determined using the method of Lowry et al.[16] The concentration of phospholipids in rat liver microsomes was measured, as described by Chen et al.[17]

Determination of microsomal membrane Ca2+ -dependent ATPase activity

Microsomal membrane Ca2+ -dependent ATPase activity was assayed in a final reaction mixture of 1 ml containing 100 mM KCl, 20mM Tris, pH 7.2, 2mM NaN3, and 1 mM MgCl2 with or without 2 mM CaCl2. Liberated inorganic phosphate (Pi) was measured by the conventional method of Fiske and Subbarow.[18] The difference in enzyme activity in the presence and absence of 2mM CaCl2 was used to calculate the Ca2+ -ATPase activity. One unit of enzyme was taken to be the amount of enzyme that released 1nmole of Pi per min.

Histopathological examinations

Freshly excised liver tissues were trimmed and fixed in 10% formalin for 24h, dehydrated in graded alcohol, cleared in xylene and embedded in paraffin. Livers were sectioned, mounted on glass slides and differentially stained with hematoxylin and eosin for light microscopic analysis. Codes were assigned to each slide and were examined by a histopathologist who was blinded to the treatment groups. Degree of damage to hepatocytes was assessed based on the following scores: Zero (0) = no cell necrosis; 1 = low cell necrosis; 2 = mild cell necrosis; 3 = moderate cell necrosis; 4 = marked cell necrosis; 5 = massive total cell necrosis.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were run in triplicates and data were expressed as mean ± SD for each group. Analysis of variance was used to calculate the statistical significance and values with P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Antioxidant phytochemicals in MECF and EF

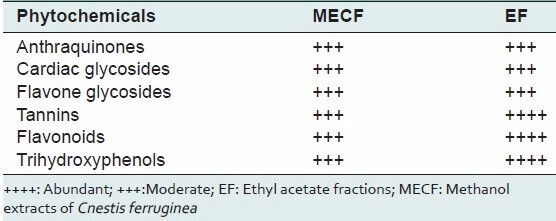

The phytochemical screening of MECF and EF revealed the presence of antioxidant phytochemicals namely cardiac glycosides, anthraquinones, tannins and polyphenolic compounds, such as flavone glycosides. Separated bands on TLC with same RF values which turned aluminium chloride to yellow, ferric chloride to blue and the purple colour of DPPH radical solution to yellow were observed in the chromatogram of MECF and EF indicating the presence of flavonoids, trihydroxyl phenol and radical scavengers, respectively [Table 1].

Table 1.

Phytochemical constituents in methanol extracts and ethyl acetate fractions of Cnestis ferruginea leaves

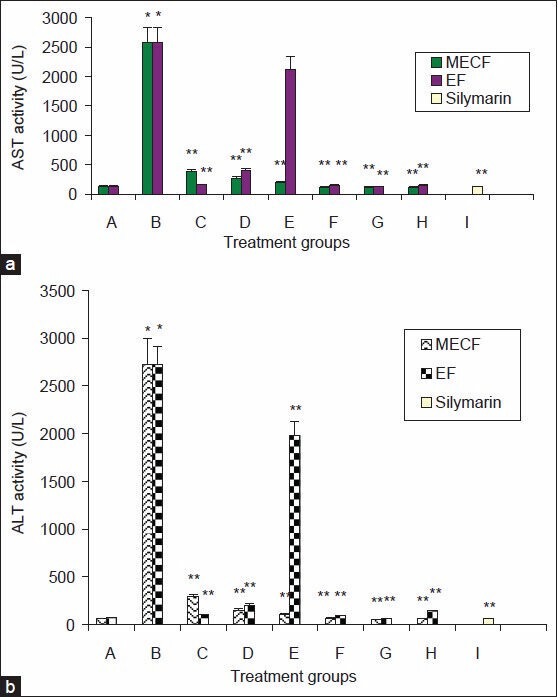

Effect of extracts on liver enzymes

The effects of MECF and EF on liver enzymes are shown in Figures 1. Administration of CCl4 alone significantly increased the activities of serum alanine amino transferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) as compared to control. Pre-treatment of rats with EF (125, 250, 500 mg/kgb.w./5 mL) significantly (P < 0.05) decreased the activities of AST by 94, 84.9, 17.7%, respectively, while the percentage reductions of 85.3%, 89.7%, 92.7%, respectively were obtained for MECF when compared with the CCl4 -only treated animals. The activities of serum ALT was also decreased by 96.3, 92.6, 27.2% in the EF-pretreated groups, whereas 89.4%, 94.5% and 96.1% reductions were obtained in the MECF pre-treated groups when compared with the CCl4 -only treated groups. At low concentrations of EF, serum ALT and AST levels were markedly reduced but as the concentration of EF increased, serum ALT and AST activities increased. The reductions by silymarin and EF (125-250 mg/kg b.w) were not significantly (P > 0.05) different from each other. The serum ALT and AST activities of rats treated with only EF or MECF were not significantly different (P > 0.05) from control. There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) in the serum levels of AST and ALT of rats treated with MECF alone compared to control. These results were also confirmed by histopathological observations [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Effects of Pre-treatment with MECF and EF on liver Enzymes (a) serum aspartate amino transferase (AST) and (b) serum alanine amino transferase (ALT) of rats administered CCl4. A.CMC + olive oil; B. CCl4 only; C. CCl4 + extract 125 mg/kg/5 ml/b.w; D. CCl4 + extract 250 mg/kg/5ml/b.w; E- CCl4 500 mg/kg/5 ml/b.w; F.- extract only (125 mg/kg/5 ml b.w); G- extract only (250 mg/kg/5 ml b.w); H. extract only (500 mg/kg/5 ml/b.w), I. CCl4 + silymarin (25 mg/kg/5ml/b.w). Values are mean ± S.D (n=5); * significantly different from control at (P <0.05). ** Significantly different from CCl4 –treated group at (P <0.05). MECF- Methanol extracts of Cnestis ferruginea, EF- ethylacetate fraction of Cnestis ferruginea

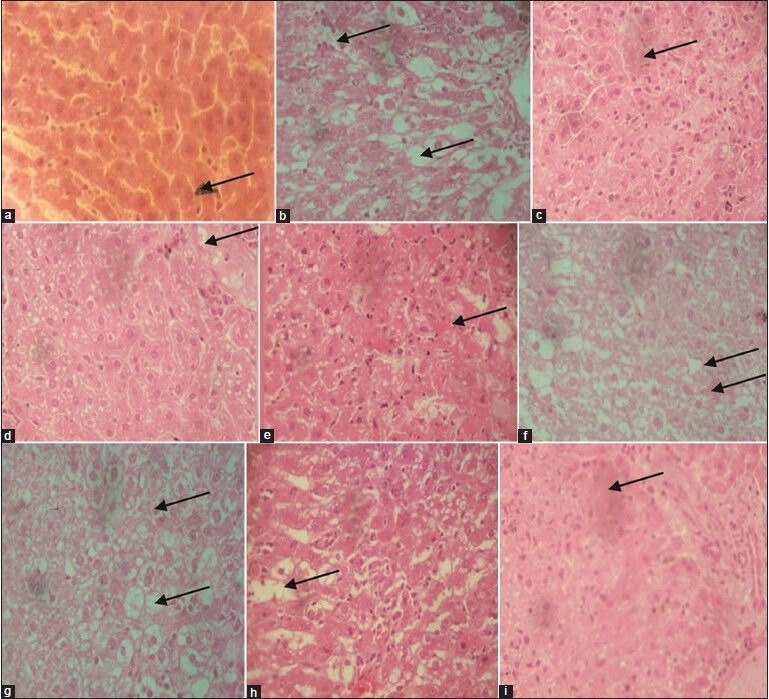

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of liver sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (×40) A. CMC + olive oil; B. CCl4 in olive oil; C. CCl4 + EF (125 mg/kg/5 mL/b.w.); D. CCl4 + EF (250 mg/kg/5mL/b.w.); E. CCl4 + EF (500 mg/kg/5 mL/b.w.); F. CCl4 + MECF (125 mg/kg/5 mL/b.w.); G. CCl4 + MECF (250 mg/kg/5 mL/b.w.); H. CCl4 + MECF (500 mg/kg/5 mL/b.w.); I. CCl4 +silymarin (25 mg/kg/5 mL/b.w.)

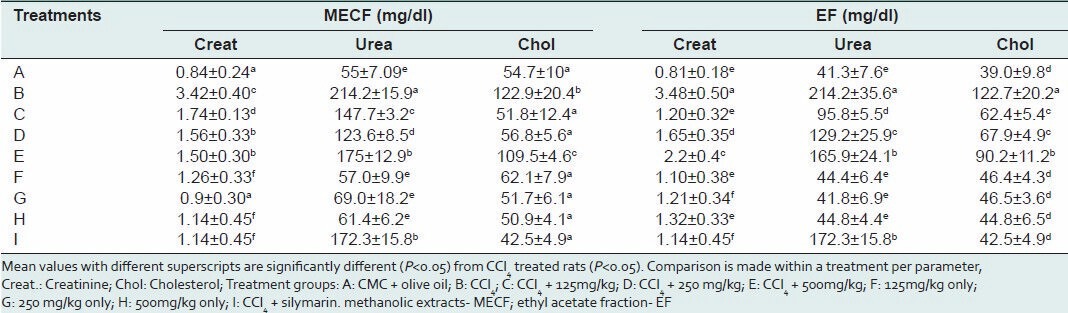

Effects of EF and MECF on Kidney function

Table 2 presents the results of kidney function test in rats administered CCl4. The levels of creatinine and urea were significantly elevated in rats administered CCl4 only. Serum creatinine levels in the CCl4 intoxicated rats were significantly reduced (P < 0.05) by 56 and 65.5% at 500 mg/kg and 125mg/kg of MECF and EF respectively, compared to CCl4 –only treated group. Serum urea levels were also decreased by 42 and 55.3% in the 250 mg/kgbw and 125 mg/kg of MECF and EF pre-treated groups respectively, while a significant increase (P < 0.05) of 18% was observed in the 500 mg/kg bw treated rats [Table 2]. Similarly, pre-treatment with silymarin decreased serum urea and creatinine levels by 20 and 67%, respectively. There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) in the serum levels of creatinine and urea in EF and MECF-treated alone rats respectively, when compared to control [Table 2].

Table 2.

Effects of pre-treatment with MECF and EF on serum creatinine, urea, and cholesterol levels in rats induced with CCl4 toxicity

Effects of extracts of EF and MECF on cholesterol metabolism

The effects of pre-treatment with MECF and EF on serum cholesterol of rats administered CCl4 intraperitoneally is as shown in Table 2. Cholesterol levels were found to be elevated in the serum of CCl4 -only treated rats compared to control. Pre-treatment with MECF and EF significantly (P < 0.05) ameliorated the level of serum cholesterol in a concentration-dependent manner. At 125, 250 and 500 mg/kgb.w of MECF serum cholesterol levels were decreased by 57.9, 53.8 and 10.9%, respectively. Similar concentrations of EF caused 49, 44.7 and 26.5% reductions in levels of serum cholesterol. The levels of cholesterol in the sera of MECF or EF-treated only rats were not significantly (P > 0.05) different from the levels in the control.

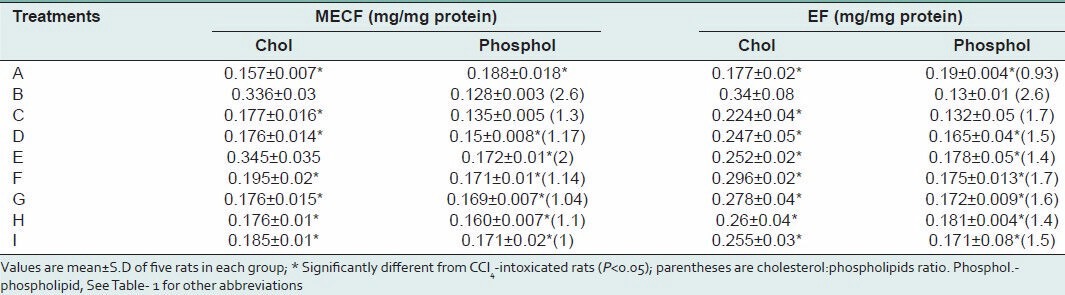

Effects of MECF and EF on CCl4 -induced microsomal membrane damage

The effects of pre-treatment with MECF and EF on liver microsomal membrane cholesterol and phospholipids content are presented in Table 3. Administration of CCl4 alone to rats significantly (P < 0.05) increased the microsomal membrane cholesterol concentrations when compared to control. The microsomal membrane concentrations of cholesterol in rat livers treated with MECF alone was not significantly different from each other and from control. In the microsomes of rats pre-treated with 500 mg/kg b.w of MECF, cholesterol level was not also significantly different from that in the CCl4 –only treated groups. Administration of lower concentrations of MECF (125 mg/kg b.w and 250 mg/kg b.w) decreased the elevated levels of cholesterol in the microsomal membranes by 47.3 and 47.6% respectively. Moreover, pre-treatment with EF (125 mg/kg b.w, 250 mg/kg b.w, 500 mg/kg b.w.) decreased microsomal membrane cholesterol concentrations by 34, 27.4 and 26%, respectively. Similarly, silymarin decreased the microsomal cholesterol concentrations by 25% [Table 2]. Rat liver microsomal membrane phospholipid concentration were significantly decreased (P < 0.05) by the intraperitoneal administration of a single dose of CCl4 by 32% when compared to control rats resulting in a significant increase in cholesterol/phospholipid mole ratio. In rats pre-treated for 72hs with MECF or EF (500 mg/kg b.w) microsomal membrane phospholipids was increased by 34.4 and 37%, respectively, compared to CCl4 only-treated animals. These significant increases caused appreciable decreases in microsomal membrane cholesterol/phospholipid mole ratio of extracts-treated groups. The concentrations of phospholipids in microsomal membrane of animals pre-treated with MECF or silymarin were not significantly different (P < 0.05) from those administered MECF alone and the control. Also the membrane phospholipid concentrations in rats co-administered CCl4 and 250 mg/kg or 500 mg/kg or silymarin (25 mg/kg b.w) were not statistically different (P < 0.05) from the EF or MECF (125, 250 and 500 mg/kg b.w treated alone and control rats, respectively [Table 3].

Table 3.

Effects of pre-treatment with MECF and EF on liver microsomal membrane cholesterol and phospholipid levels in rats administered CCl4 intraperitoneally

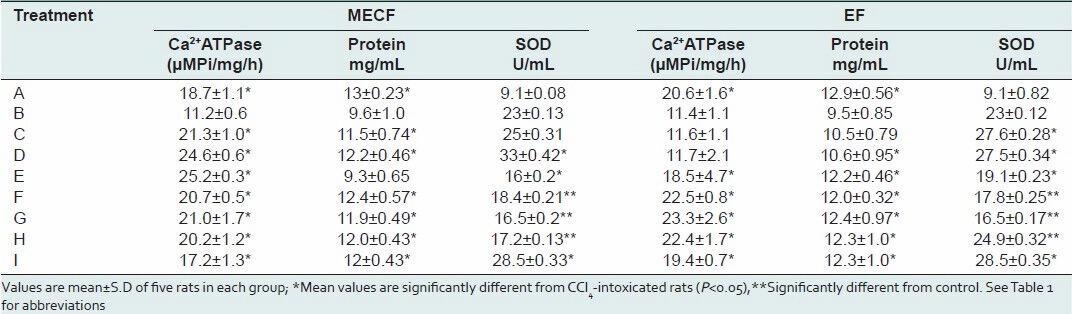

Effects of MECF and EF on total microsomal membrane protein concentrations and Ca2+ -ATPase activity

The results of the effects of extracts on membrane proteins are presented in Table 4. Microsomal membrane protein concentrations were significantly (P < 0.05) depressed in rats treated with CCl4 by 26%. Previous administration of EF or MECF protected the microsomal membrane proteins from destruction as indicated by the elevated levels of microsomal membrane proteins. Specifically, in rats pre-treated with MECF or EF (500 mg/kg), the decreases in microsomal membrane protein concentrations were by 6%, respectively compared to control animals. Pre-treatment with silymarin caused a decrease of 8% of control in microsomal protein concentration. Microsomal protein concentrations of MECF or EF-treated only rats were not significantly different (P > 0.05) from control animals [Table 4].

Table 4.

Effects of MECF and EF on protein concentrations, SOD and Ca2+ ATPase activities in the liver microsomal membranes of rats induced with CCl4 toxicity

The specific activity of hepatic endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ -ATPase of rats injected with CCl4 decreased by 40% of control [Table 4]. In rats previously-administered graded doses of MECF (125, 250 and 500 mg/kg b.w.), the specific activity of the enzyme was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in CCl4 -only treated animals by 89.3%, 118.5% and 125%, respectively. There was no significant effect on the enzyme activity at 125 and 250 mg/kg b.w of EF, 500 mg/kg b.w increased the enzyme activity by 62% compared to the CCl4 -only treated animals. The observed increases in enzyme activity in EF (500 mg/kg b.w.) or silymarin-treated CCl4 -intoxicated rats were not significantly different from that in EF or MECF only treated and control rats. Similarly, the activity of Ca2+ -ATPase was increased by 53.6% in the silymarin pre-treatment rats.

Effects of MECF and EF on liver superoxide dismutase activity

Table 4 shows the activity of SOD in the liver. A significant increase of 60.4% was observed in the SOD activity of rats administered only CCl4 as compared to control. SOD activity was further increased significantly (P < 0.05) in rats pre-treated with 125 and 250 mg/kg of MECF or EF or silymarin and challenged with CCl4, respectively compared to CCl4 only-treated rats. Though, the SOD activity of rats administered 500 mg/kg EF or MECF and CCl4 decreased, this enzyme activity was significantly greater than in control. Furthermore, SOD activity was significantly elevated in rats pre-treated with only MECF or EF as compared to control.

Histopathology of the liver

Figure 2, shows the photomicrographs of liver sections of control, CCl4 –intoxicated, 125, 250 and 500 mg/kg b.w. of EF, MECF and silymarin plus CCl4 -intoxicated rats, respectively. Liver sections of control rats showed normal cellular architecture with distinct hepatic cells, sinusoidal spaces and central vein [Figure 2a]. There were disarrangement of normal hepatic cells, massive fatty degeneration, multifocal centrilobular hepatic necrosis, and cellular infiltration in CCl4 -only -treated rats [Figure 2b]. Livers of rats pre-treated with EF (125 mg/kg) and MECF (500 mg/kg b.w.) showed few small foci centrilobular necrosis, and fatty degenerations [Figure 2c and h]; mild small foci centrilobular necrosis and fatty degenerations were observed in livers of rats pre-treated with EF (250 mg/kg) [Figure 2d], and MECF (250 mg/kg) Figure 2g; marked small foci centrilobular necrosis, and fatty degenerations were observed in livers of rats pre-treated with EF (500 mg/kg) Figure 2e and MECF (125 mg/kg) Figure 2f.

DISCUSSION

Among the known hepatotoxicants, CCl4 is the best characterized model of xenobiotic and oxidative stress-induced hepatotoxicity, commonly used for screening of anti-hepatoprotective activity of drugs. It is also well established that this free radical –induced hepatic damage can be prevented or reduced by antioxidants.[19] The present study, revealed the presence of phytochemicals such as cardiac glycosides, anthraquinones and tannins in methanol extracts of leaves of Cnestis ferruginea. Mixture of compounds of the same RFs were found in MECF and EF but were more concentrated in EF. These compounds formed a yellow complex with aluminium chloride indicating the presence of flavones. Furthermore, they formed a blue – black complex with ferric chloride and were therefore identified as trihydroxyl phenols. The purple colour of DPPH radical was bleached to yellow because these phenolic compounds were able to donate electrons to and reduce the DPPH radical to DPPH-H, thus revealing their radical scavenging property.[20] These findings support our earlier report on the antioxidant property of the leaves of Cnestis ferruginea, and its compounds- robustaside B and para-hydroxyphenol which were isolated and characterized.[10] On this basis, the hepato-protective capacity of MECF and EF in rats induced with CCl4 -toxicity was compared.

Increased serum levels of ALT and AST in livers induced with CCl4 toxicity is an indication of damaged structural and functional integrity of the liver cell membranes since, these cytosolic enzymes are only released into circulation after hepatic cellular damage.[21] However, livers of rats pre- administered MECF and EF for 72 h were effectively protected against toxic injury from CCl4 as evident in the concentration-dependent decreases in the liver enzymes activities [Figure 1]. The livers were markedly protected at 125 mg/kg of EF and 500 mg/kg of MECF. These concentrations of the extracts were well tolerated and efficacious for the hepatoprotection observed in this study. Indeed, 125 mg/kg b.w. of EF was sufficiently effective for the hepato-protection perhaps because EF is purer and possibly contains a higher concentration of the hepatoprotective bioactive principles. Moreover, saponins and alkaloids were reported to be present in root extracts of Cnestis ferruginea which may account for the observed apparent toxicity of EF at high doses.[22,23] On the contrary, pre-treatment with MECF and EF alone did not show any significant (P > 0.05) elevation in the amino transferases activities and all the biochemical parameters when compared to control. This finding is another pointer to the safety of these extracts for consumption at these concentrations, and agrees with previous reports on the non-toxic nature of Cnestis ferruginea leaves.[9]

In the adopted mechanism of CCl4 hepatotoxicity by reductive dehalogenation catalyzed by P450, highly reactive trichloromethyl (CCl3) free radical formed readily interacts with molecular oxygen to form the trichlomethyl peroxyl radical (CCl3 OO).[1] These radicals bind to proteins, lipids or abstract a hydrogen atom from an unsaturated lipid to initiate lipid peroxidation and liver damage, thereby contributing majorly to the pathogenesis of diseases.[24] Therefore, the possibility of a defect or damage to the kidney or other enzymatic pathways in the liver cells cannot be ruled out. There have been controversial reports concerning the levels of biomarkers of kidney function in CCl4 -induced toxicity. Ogeturk et al.,[25] observed a decrease in serum urea and creatinine levels after a subcutaneous administration of 0.5 mL/kg of CCl4 every other day for a month to rats. While Manna et al.,[26] attributed the short period of oral exposure of CCl4 (1 mL/kg for 2 days) to mice in their study as being responsible for the constancy in their serum levels of urea nitrogen and creatinine. Moreover, a recent report demonstrated a decrease and increase in plasma levels of urea and creatinine, respectively after acute intraperitoneal administration of CCl4 (1 mL/kg in corn oil) to rats.[27] Our data is at variance and showed that a single intraperitoneal administration of CCl4 (1.5 mL/kg b.w. of 20% CCl4 in olive oil) elevated the serum levels of creatinine and urea. The observed increase is indicative of an impairment of glomerular function and renal disorder.[28] Specifically, the increased creatinine level suggests that muscular wasting occurred during CCl4 intoxication since creatinine production has a direct relationship with muscle mass.[29] Consequently, muscle proteins are depleted and increasingly deaminated but the associated renal disorder precludes normal excretion process and therefore, caused accumulation and elevation of urea and creatinine levels in the serum. Indeed, the dose, the length of time and route of administration determines the extent of renal damage during CCl4 intoxication. MECF and EF pre-administration attenuated the impairment considering the marked dimunitions in the levels of these biomarkers in the extract pre-treated animals. The nephro-protection elicited by Cnestis ferruginea seems possible because the kidney as an excretory organ might be accumulating some of the bioactive principles in the extracts. These findings agree with earlier report on the nephroprotective potential of Cnestis ferruginea in streptozotocin-induced diabetes.[9] However, the presence of several compounds in MECF seems to be interfering with the extent of nephro-protection offered.

Administration of CCl4 elevated the cholesterol levels in rat serum and liver microsomal membranes while the membrane phospholipids were reduced. The increased cholesterol/phospholipid ratio caused by CCl4 administration indicates that the membrane integrity and fluidity has been compromised. This is not unconnected with a derangement in lipid metabolism which forms the bedrock for the altered membrane functions and integrity. Fadok et al.,[30] reported that cells undergoing apoptosis showed characteristic loss of phospholipid asymmetry and phosphatidyl serine expression for recognition and uptake by phagocytic cells. MECF and EF pre-administration attenuated the cholesterol levels in the serum and microsomal membranes and increased the amount of membrane phospholipids in the liver microsomes which resulted in a decreased cholesterol/phospholipid ratio. It implies that these extracts could ameliorate CCl4 -induced cell death as observed in the decreased centrilobullar necrosis and fatty degenerations in the molecular architecture of the extract-pre-treated rat livers. It could mean that the extracts interfered with. CCl3 radicals responsible for radical chain reactions on membrane PUFAs to prevent peroxidation, destruction of membrane integrity and alteration of lipid metabolism. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ -ATPase plays a critical role of maintaining the cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis.[31] In the CCl4 only-treated groups, microsomal membrane Ca2+ -ATPase was inactivated and total protein content decreased as reported earlier by Hemmings et al.[32] The enzyme inactivation and protein depletion which is an indication of dysregulated intracellular calcium ion concentrations were reversed by prior administration of MECF and EF. The observed decrease in microsomal membrane phospholipid levels might be contributory to the inactivation of the Ca2+ -ATPase in the CCl4 only-treated groups since acidic phospholipids and polyphosphoinosides are among the physiological activators of the pump.[33,34] The involvement of microsomal Ca2+ -ATPase in the regulation of cytosolic Ca2 + concentration and hormonal mechanisms is interconnected to other biochemical pathways responsible for the physiological well-being of the organisms. Therefore, the protection of microsomal membrane fluidity, Ca2+ -ATPase activity and integrity by Cnestis ferruginea is highly significant, crucial and critical in preventing cytosolic calcium overload, alteration of calcium homeostasis and ultimately mitochondrial-mediated cell death inducible by CCl4 toxicity.

Superoxide dismutases are known to catalyze the dismutation of superoxide anion into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide.[35] Superoxide dismutase activity in liver microsomes were markedly increased, probably in response to increased generation of O2.- produced from the free radical chain reactions initiated by CCl3. and CCl3 OO. SOD activity was further increased in the presence of MECF or EF and CCl4, as well as when plant extracts were administered alone which suggest that the extracts might have the potential to induce the endogenous antioxidant defenses by up-regulating the expression of the genes coding for SOD.[36] Perhaps, the constituent robustaside B, para-hydroxyphenol and other polyphenolic compounds in EF and MECF were responsible for the observed hepatoprotection by scavenging the CCl3., generated after biotransformation of CCl4 in the rat liver which inadvertently are the causative agents of liver damage, loss of membrane fluidity and dysregulation of Ca2 + homeostasis through inactivation of Ca2 + ATPase. This proposed mechanism of hepatoprotection for Cnestis ferruginea correlates with that of previous reports on the mechanism of protection against CCl4 -induced hepatotoxicity by plant extracts possessing free radical scavenging activity.[37]

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our findings revealed that methanol extracts of Cnestis ferruginea (500 mg/kg) and ethyl acetate fraction (125 mg/kg) possess hepato- and nephro-protective properties attributable to the bioactive principles which are polyphenolics with radical scavenging potential. Furthermore, this study has proven that methanol and ethyl acetate extracts of Cnestis ferruginea effectively preserved the microsomal membrane integrity, fluidity, modulated Ca2+ -ATPase activity, and induced superoxide dismutase activity in the course of their hepatoprotection. Thus; suggesting that the strong hepatoprotective activity of leaf extracts of Cnestis ferruginea is possibly through the modulation of the liver cellular Ca2 + homeostasis and antioxidant- mediated mechanisms of action.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSDW) Postgraduate Fellowship given to Dr R.A Adisa which was utilized at H.E.J. Research Institute of Chemistry, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brent JA, Rumack BH. Role of free radicals in toxic hepatic injury II. Are free radicals the cause of toxin-induced liver injury? J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1993;31:173–96. doi: 10.3109/15563659309000384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrabi K, Kaul N, Ganguly NK, Dilawari JB. Altered calcium homeostasis in CCl4 exposed rat hepatocytes. Biochem Int. 1989;18:1287–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olorunsogo OO, BababunmI EA, editors. Proceedings of IPCS/IUPHAR Toxicology Workshop, Buenos Aires, Argentina and IUPHAR/IPCS/PIMRAT International Workshop on Drug Metabolism and Toxicology, Nigeria; WHO/IPCS/93.41; 1993. Plasma membrane ion motive ATPases applicable to toxicological studies. Chemical Safety Metabolism and Toxicity-selected lectures; pp. 101–12. 47. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maksimovic Z, Kovacevic N, Lakusic B, Cebovic T. Antioxidant activity of yellow dock (Rumex crispus L., Polygonaceae) fruit extract. Phytother Res. 2011;25:101–5. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanmugapriya E, Venkataraman S. Studies on hepatoprotective and antioxidant actions of Strychnos potatorum Linn. seeds on CCl4-induced acute hepatic injury in experimental rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;105:154–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Toumy SA, Omara EA, Brouard I. Artimesia monosperma against CCl4-induced hepatic damaged rat. Australian Journal Basic Appl Sci. 2011;5:157–64. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parvez M, Rahman A. A novel antimicrobial Isoflavone Galactoside from Cnestis ferruginea (Connaraceae) J Chem Soc Pak. 1992;14:221–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adisa RA, Oke JM, Olomu SA, Olorunsogo OO. Inhibition of human haemoglobin glycosylation by flavonoid-containing leaf extracts of Cnestis ferruginea. J Cam Acad Sci. 2004;4(Suppl):351–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adisa RA, Choudhary MI, Adewoye EO, Olorunsogo OO. Hypoglycaemic and Biochemical Properties of Cnestis ferruginea. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2010;7:185–94. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v7i3.54774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adisa RA, Khan AA, Oladosu IA, Ajaz A, Choudhary MI, Olorunsogo OO, et al. Purification and Characterization of phenolic compounds from the leaves of Cnestis ferruginea (De Candolle): Investigation of antioxidant property. Res J Phytochem. 2011;5:177–89. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trease GE, Evans WC. Pharmacognosy. 12th ed. London, Philadelphia: Bailliere Tindall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergmeyer HU, Gawey K, Grassal M. Enzymes as Biochemical Reagents. In: Bergmeyer HU, editor. Methods in Enzymatic Analysis. London: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 425–522. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trinder P. Determination of glucose in blood using glucose oxidase with an alternative oxygen acceptor. Ann Clin Biochem. 1969;6:24–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rifai N, Bachorik PS, Albers JJ. Lipids, lipoproteins and apolipoproteins. In: Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, editors. Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1999. pp. 809–61. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marklund S. Distribution of CuZn superoxide and Mn superoxide dismutase in human tissues and extracellular fluids. Acta physiol Scand. 1980;492(Suppl):S19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowry OH, Rosenbrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen PS, Toribara JV, Huber W. Micro determination of phosphorus. Anal Chem. 1956;28:1756–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiske CH, Subbarrow Y. The colorimetric determination of phosphorus. J Biol Chem. 1925;66:375–400. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dahiru D, Mamman DN, Wakawa HY. Ziziphus mauritiana fruit extract inhibits CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity in male rats. Pak J Nutr. 2010;9:990–3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takao T, Kitatani F, Watanabe N, Yagi A, Sakata K. A simple method for antioxidants and isolation of several antioxidants produced by marine bacteria from fish and shell fish. J Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58:1780–3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Recknagel RO, Glende EA, Jr, Dolak JA, Waller RL. Mechanisms of CCl4 toxicity. Pharmacol Ther. 1989;43:139–54. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(89)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishola IO, Akindele AJ, Adeyemi OO. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of Cnestis ferruginea Vahl ex D.C (connaraceae) methanolic root extract. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;135:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atere AG, Ajao AT. Toxicological implications of crude alkaloidal fraction from Cnestis ferruginea D.C root on liver function indices of male Wistar rats. Int J Biomed Health Sci. 2009;5:145–56. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. Role of free radicals and catalytic metal ions in human disease: An overview. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:1–85. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86093-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogeturk M, Kus I, Colakoglu N, Zararsiz I, Ilhan N, Sarsilmaz M. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester protects kidneys against CCl4 toxicity in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manna P, Sinha M, Sil PC. Aqueous extract of Terminalia arjuna prevents CCl4 induced hepatic and renal disorders. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bashandy SA, AlWasel SH. CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity in rats: protective role of vitamin C. J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;6:283–92. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perrone RD, Madias NE, Levey AS. Serum creatinine as an index of renal function: New insights into old concepts. Clin Chem. 1992;38:1933–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banfi G, Del Fabbro M. Relation between serum creatinine and body mass index in elite athletes of different sport disciplines. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:675–8. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.026658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fadok VA, De Cathelineau A, Daleke DL, Henson PM, Bratton DL. Loss of phospholipid asymmetry and surface exposure of phosphatidyl serine is required for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages and fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1071–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lytton J, Westlin M, Burk SE, Shull GE, MacLennan DH. Functional comparisons between isoforms of the sarcoplasmic or endoplasmic reticulum family of calcium pumps. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14483–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hemmings SJ, Pulga VB, Tran ST, Uwiera RE. Differential inhibitory effects of CCl4 on the hepatic plasma membrane, mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticular calcium transport systems: Implications to hepatotoxicity. Cell Biochem Funct. 2002;20:47–59. doi: 10.1002/cbf.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niggli V, Adunyah ES, Penniston ST, Carafoli E. Purified (Ca 2+ +Mg 2+)-ATPase of the erythrocyte membrane. Reconstitution and effects of calmodulin and phospholipids. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:395–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choquette D, Hakim G, Filoteo AG, Plishker GA, Bostwick JR, Penniston S. Regulation of plasma membrane Ca 2+-ATPase by lipids of the phosphatidyl inositol cycle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;125:908–15. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91369-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zelko I, Mariani T, Folz R. Superoxide dismutase multigene family: A comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2) and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution and expression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:337–49. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00905-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamalakannan N, Rukkumani R, Aruna K, Varma PS, Viswanathan P, Menon VP. Protective effect of N-acetyl cysteine in CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Iran J Pharmacol Ther. 2005;4:118–23. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsiao G, Lin YH, Lin CH, Chou DS, Lin WC, Sheu JR. The protective effects of PMC against chronic CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity in-vitro. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001;24:1271–6. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]