Abstract

Background:

Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) frequently hampers implementation of ambulatory surgery in spite of so many costly antiemetic drugs and regimens.

Objective:

The study was carried out to compare the efficacy of ginger (Zingiber officinale) added to Ondansetron in preventing PONV after ambulatory surgery.

Materials and Methods:

It was a prospective, double blinded, and randomized controlled study. From March 2008 to July 2010, 100 adult patients of either sex, aged 20-45, of ASA physical status I and II, scheduled for day care surgery, were randomly allocated into Group A[(n = 50) receiving (IV) Ondansetron (4 mg) and two capsules of placebo] and Group B[(n = 50) receiving IV Ondansetron (4 mg) and two capsules of ginger] simultaneously one hour prior to induction of general anaesthesia (GA) in a double-blind manner. One ginger capsule contains 0.5 gm of ginger powder. Episodes of PONV were noted at 0.5h, 1h, 2h, 4h, 6h, 12h and 18h post- operatively.

Statistical Analysis and Results:

Statistically significant difference between groups A and B (P < 0.05), was found showing that ginger ondansetron combination was superior to plain Ondansetron as antiemetic regimen for both regarding frequency and severity.

Conclusion:

Prophylactic administration of ginger and ondansetron significantly reduced the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting compared to ondansetron alone in patients undergoing day care surgery under general anaesthesia.

Keywords: Ambulatory (day care) surgery, American Society of Anaesthesiologists, Ginger (Zingiber officinale), Post-operative nausea and vomiting, Visual Analogue Score

INTRODUCTION

Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are one of the most common and distressing adverse events experienced by patients after an anaesthesia and surgery[1,2] may prolong recovery, electrolyte disturbances. The efforts of vomiting can cause wound dehiscence and even aspiration of gastric content, in certain situations it may delay patient discharge and increase in hospital costs.[1,2] Prevention and treatment of PONV help to accelerate post- operative recovery and increase patient satisfaction.[3,4] PONV is not uncommon after general surgery with incidence of 20-30%.[5,6] PONV causes 0.17% un-anticipated admission to the hospital following ambulatory surgery.[7]

Numerous studies have investigated the prevention and treatment of PONV for patients scheduled to undergo day care surgeries by a variety of antiemetics including anticholinergics,[8,9] antihistamines,[10] promethazine,[11] butyrophenones like haloperidol[12] and droperidol.[13] However, these agents may cause undesirable adverse effects such as excessive sedation, hypotension, dry mouth, dysphoria, hallucinations, and extrapyramidal signs.[14] 5-HT3 antagonists prevent serotonin from binding to 5-HT3 receptors on the ends of the vagus nerve's afferent branches, which send signals directly to the vomiting center in the medulla oblongata and in the chemoreceptor trigger zone of the brain.[15] By preventing activation of these receptors, 5-HT3 antagonists interrupt one of the pathways leading to vomiting.[15] Ondansetron, a commonly used prophylactic 5-HT3 antagonist, was found to be more effective than traditional antiemetics, like droperidol and metoclopramide, in reducing the incidence of PONV.[16,17,18]

Ginger (Zingiber officinale) has traditionally been used in China for more than 2000 years for gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea[19] and vomiting. Ginger has been used as an antiemetic after chemotherapy,[20,21] motion sickness,[22] Gynecological Surgery,[23] gynaecological laparoscopic surgeries,[24] gynaecological day care surgeries.[25] Recent evidences suggest that its antiemetic activities may be derived from its antiserotonin-3 (5HT3) effect on both central nervous and gastrointestinal systems.[26,27]

The aim and objective of this study was to compare the antiemetic efficacy of ginger in combination with ondansetron vs plain ondansetron in the first 18 h post-operative period of a day care surgery. The severity of PONV was recorded using VAS with choice options ranging from 0 (no nausea) to 10 (worst possible nausea).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining permission from institutional ethics committee, written informed consent was taken. Total 100 adult patients were randomly allocated to two equal groups (n = 50 in each group) using computer generated random number list. Group A comprised patients who received single dose IV Ondansetron (4 mg) along with two capsules of placebo and group B comprised those who received IV Ondansetron (4 mg) and two capsules of ginger (0.5 mg ginger in each), one hour before induction of GA. Capsules were swallowed with sips of water in presence of resident doctor not taking part in study.

Exclusion criteria

Patient's refusal of any known allergy or contraindication to ondansetron or ginger, pregnancy, lactating mothers and children, subjects who vomited or received antiemetics within 24 h before surgery, hepatic, renal or cardiopulmonary abnormality, alcoholism, diabetes, significant gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., peptic ulcer disease or gastro esophageal reflux disease) and motion sickness were excluded. As we were dealing with day care surgery patients having no assistance in home and dwelling at more than 10 Km from our institution were also excluded from our study.

In pre-operative assessment, patients were enquired about heartburn, belching and abdominal discomfort, h/o motion sickness, any antiemetic treatment received, h/o previous exposure to anaesthesia and h/o PONV. The patients were enquired about any history of drug allergy, previous operations or prolonged drug treatment. General examination, Systemic examinations and Assessment of the airway were done. Preoperative fasting of minimum 6h was ensured before operation in all day care cases. All patients received premedication of tablet diazepam 10mg orally the night before surgery as per pre-anesthetic check up direction to allay anxiety, apprehension and for sound sleep. The patients also received tablet ranitidine 150 mg in the previous night and in the morning of operation with sips of water.

The patients were pre-oxygenated with 100% oxygen for a period of 5 min. Injection fentanyl (2 μg/kg) and glycopyrrolate (0.01 mg/kg) were given intravenously 3 min before induction of anaesthesia. All the patients were induced with IV injection of propofol 10% (2 mg/kg). After that, atracurium (0.5 mg/kg) was given to facilitate laryngoscopy and intubation. Controlled ventilation was maintained with 33% oxygen in 67% nitrous oxide using Boyle's apparatus. Laryngoscopy, intubation and cuff inflation were completed within 15 sec in all cases. Muscle relaxation was maintained with intermittent intravenous atracurium (0.2 mg/kg) as and when required. Intra-operatively, pulse rate, respiratory rate, arterial oxygen saturation, ECG, capnography, systolic and diastolic pressure, were monitored continuously. Ventilation was controlled manually and adjusted to maintain the End tidal CO2 pressure (ET CO2) between 35-45 mmHg. Laparoscopic surgeries were performed under video guidance and involved four punctures of the abdomen and abdomen insufflated with carbon- dioxide through a veress needle to a maximum intra-abdominal pressure of 14 mmHg. At the completion of surgery, residual neuro-muscular blockade was antagonized at TOF ratio >0.7 with neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.01 mg/kg intravenously and patient was extubated in awaken condition. All the patients received tramadol 2 mg/kg IV 20 min before the end of surgery. The patients were then sent to the post-operative recovery unit. Post-operative analgesia was provided with injection diclofenac 50 mg intramuscularly. All patients received moist oxygen supplementation (3 liter/min) for 2 h and standard minimum monitoring systems were used. All the patients were on intravenous drip and did not have any oral fluid during the study period of 12 h.

Throughout the 18 h post-operative period, all the parameters were recorded on 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 18 hrs. All episodes of nausea, retching, vomiting and rescue antiemetic provided were recorded by using score of Bellville and co-workers[28] which was the primary assessment parameter. Severity of PONV was observed by VAS scoring (0 represent "no nausea" and 10 represents "worst possible nausea") at same interval in post-operative period. The time to first administration of rescue antiemetic and the total dose of rescue antiemetic were also recorded. If the patient experienced emetic episodes, retching or requested for treatment, rescue antiemetic was given with IV Metoclopramide (10 mg) very slowly. Any patient who had experienced multiple episodes of emesis or retching received only single dose of Metoclopramide in a 12 h period.

Statistical analysis

The raw data were entered into Microsoft excel spread sheet and analyzed by appropriate statistical software SPSS® statistical package version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normally distributed numerical variables were compared between groups by independent sample T test. Chi square test, Officers exact test and Fischer's exact test were used to compare categorical variables between groups. All analysis was two tailed and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

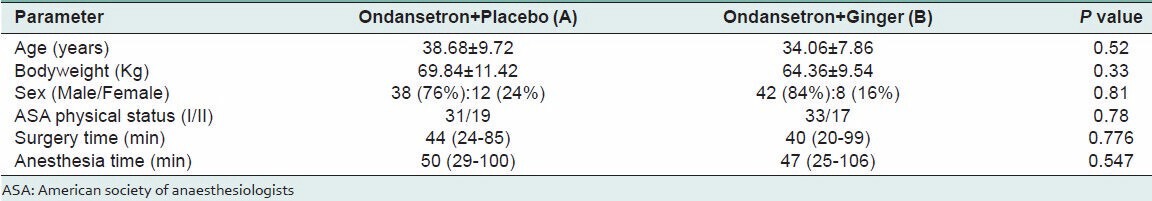

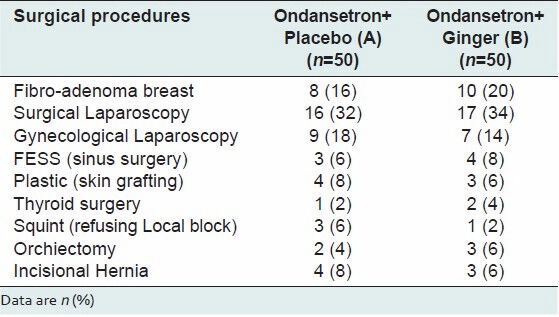

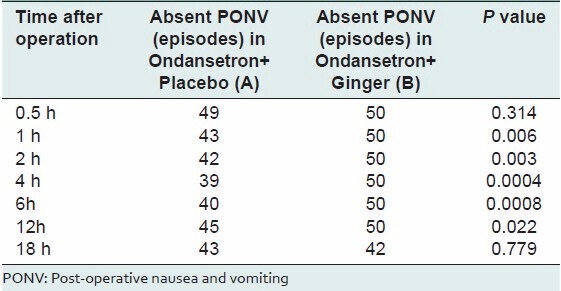

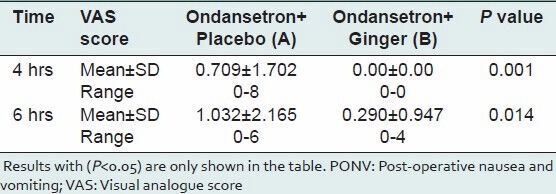

There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of demographic characteristics of the patients namely age, sex and body weight, ASA status, duration of anaesthesia and surgery [Table 1]. Table 2 shows that type of surgical procedures were almost similar in both the groups and has no statistical significance. From Table 3 it is clear that at 0.5h and 18h episodes of PONV are not significantly different among the two groups but other readings show ginger along with ondansetron (group B) has controlled PONV more significantly than plain ondansetron (group A). Post-operative mean VAS Scoring (in 18h post-operative period) for the severity of PONV between the two study groups at same time intervals [Table 3] showed that at fourth and sixth post operative hour period, there was statistically significant difference between groups A and B (P < 0.05), showing that severity of PONV is more in case of plain ondansetron than ginger ondansetron combination.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic data between the two study groups

Table 2.

Ambulatory surgical procedures for randomized patient groups

Table 3.

Comparing the post-operative mean PONV episodes (in 12h post operative periods) between the two study groups at succeeding time intervals

Again during the 18 h post-operative study period, the comparison of mean pulse rate, respiratory rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure showed that there was no clinically significant difference between the groups.

DISCUSSION

Day care surgery has proven over the years as the best method to reduce the burden on the health care resources as well as achievement of extreme patient satisfaction.[29] In developing countries like India, most of the patients avoid bearing expenses of prolonged hospital stay. At the same time infrastructure in our country is not organized uniformly to smoothly deliver the day care procedures. In the present day scenario, PONV still remains a big headache and nuisance for the surgeons and anesthesiologists as well as an irritating discomfort for the patients almost equal in intensity to pain.[30] The delayed convalescence, hospital readmission, delayed return to work of ambulatory patients; post-operative surgical morbidities such as pulmonary aspiration, wound dehiscence, bleeding from the wound, dehydration, electrolyte disturbances and metabolic derangement due to excessive emetic episodes are few of the adverse consequences of the PONV.[31]

Various drugs regimens and antiemetic interventions have been tried from time-to-time for prevention of PONV but with a variable success rate. Many herbs like ginger, peppermint, lemon, cloves, cinnamon, basil etc., are also in the light of this intelligent and scientific research.

Ginger (Zingiber officinale) has been used for medicinal purposes since antiquity. In particular, it has been important plant for the traditional Chinese and Indian pharmacopoeia. One of its indications has always been the treatment of nausea and vomiting. Ginger is on the FDA's GRAS (generally recognized as safe) lists. The pharmacological activity is thought to lie in pungent principles (gigerols and shagaols) and volatile oils[32] (sesquiterpenes and monoterpenes). Ginger acts within the gastrointestinal tract by increasing tone and peristalsis due to anticholinergics (M3) and antiserotonin (5 HT3) action.[33] Ginger avoids the central nervous system side effects caused by most antiemetic drugs.[32]

The present study was carried out mainly to see the comparative efficacy of ginger vs placebo when added to ondansetron for preventing PONV in ambulatory surgery.

The demographic profile (age, sex, body weight, ASA status) between two groups which was statistically insignificant (P > 0.05) of our patients was quite similar with other research investigations and provided us the uniform platform to evenly compare the results obtained. A study conducted by Apariman, et al.,[34] in a total of 60 patients yielded similar results. The mean duration of anaesthesia and surgery were almost comparable in both the groups with no significant statistical difference [Table 1].

From Table 2 it is quite evident that types of surgical procedures were almost similar in both the groups and has no statistical significance.

The incidence of PONV is very less in both the groups [Table 3] within first half hour and is not statistically significant (P > 0.05) but with passage of time plain ondansetron (placebo) treated A group shows signs of PONV. In all the readings 1-12 h, group A (placebo + Ondansetron) patients suffered a significantly high (P < 0.05) amount of PONV in comparison with group B (ginger + ondansetron). Again at 18th h PONV episodes has become comparable among two groups. Our results in the first 18h period with ginger are quite comparable with many other studies[23,25,34,35] but comparison in a day care setting with a background of ondansetron treatment has not been demonstrated by any literary evidence. Background ondansetron treatment is ethically important particularly for placebo group as all the surgical procedures under GA here have emetogenic potential

The post-operative mean VAS Scoring (in 24h post-operative period) between the two study groups at succeeding time intervals was compared which showed no significant difference between two groups at 0.5, 1, 2, 12,18th h but at 4th and 6th h statistically significant difference found between groups A and B (P < 0.05), [Table 4] suggesting that the severity of PONV was more after 2nd h in case of ginger than placebo.

Table 4.

Comparing the post-operative mean VAS scoring (in 12 h post operative periods) for severity of PONV between the two study groups at succeeding time intervals

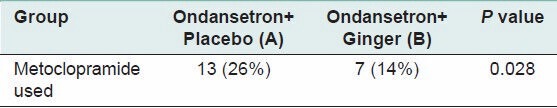

Analysis of the primary outcome variable (need for rescue antiemetic metoclopramide 10mg slow iv; Table 5) indicated that 26% (13 of 50) of patients receiving placebo required rescue antiemetic therapy, compared with 14% (7 of 50) of patients receiving ginger which is undoubtedly statistically significant (P < 0.05). Although the ginger group was superior, both groups had a good number of patients who experienced PONV even after day care surgeries. There were some patients who had multiple episodes of nausea and vomiting especially in the first 18h in both the groups but for comparison sake we included only the number of episodes and not the number of patients.

Table 5.

Comparison of rescue antiemetic (Metoclopramide) use frequency between the Study groups

Similar study conducted by Bone et al.,[23] in 60 female patients; undergoing major gynaecological surgery; were randomly allocated into 3 equal groups – placebo, metoclopramide and ginger. They concluded that ginger was superior to placebo in terms of preventing vomiting and reducing the severity of nausea. It had well comparable results with that of metoclopramide. Rescue antiemetic administration had a similar result.

Pongprojpaw D and Chiamchanya C[25] compared the antiemetic efficacy of ginger and placebo; with 40 patients in each group; and established the superiority of ginger over placebo in controlling PONV in gynecological laparoscopy with nausea 30% and 57.50% respectively.

Apariman et al.,[34] studied the comparison of ginger with placebo for prevention of PONV in patients undergoing gynecological laparoscopy. At 6h the incidence of vomiting was lower in ginger (23.3%) than the placebo (46.7%) group.

Though we have a similarity in results with the above mentioned authors Eberhart et al.,[36] commented that Ginger failed to reduce the incidence of PONV after laparoscopic surgery. Again Visalyaputra et al.,[37] concluded that ginger powder, in the dose of 2g, droperidol 1.25mg or both were ineffective in reducing the incidence of PONV after day case gynaecological laparoscopy.

It seems from the study, that single dose oral ginger powder containing capsule (1gm) has better efficacy than placebo with the background administration of ondansetron in reducing the incidence of emesis over first 18h postoperative period, in patients undergoing day care surgery under GA. A strict control group cannot be included in our study because we regarded it as unethical to withhold any prophylaxis in these patients for PONV particularly when being posted for ambulatory surgery. Another limitation of our study was the failure to obtain information after 18-h period.

The route of ginger usage is limited with no parenteral administration. Oral form of ginger as premedication may be the problem of anesthetic process. Capsule preparation may protect gastrointestinal irritation but it is difficult to swallow especially if preoperative fluid intake is limited. The other consideration is that ginger is an herbal medicine, so there is no definite quality control of the preparation.

CONCLUSION

Based on the results of our study, we can conclude that ginger is an effective therapeutic option in the prevention of PONV. Because of its widespread availability, low cost, and great tolerability profile, ginger may be an attractive option, at least as a component in the combined antiemetic regimen, especially in countries in which cost of care is a major issue. With the availability of more data, the exact role of ginger as an antiemetic in the PONV setting may be elucidated.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Watcha MF, White PF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Its etiology, treatment, and prevention. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:162–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gan TJ, Meyer T, Apfel CC, Chung F, Davis PJ, Eubanks S, et al. Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:62–71. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000068580.00245.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stadler M, Bardiau F, Seidel L, Albert A, Boogaerts JG. Difference in risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:46–52. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tramer MR. Strategies for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2004;18:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philip BK. Patients' assessment of ambulatory anesthesia and surgery. J Clin Anesth. 1992;4:355–8. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(92)90155-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gan TJ, Meyer TA, Apfel CC, Chung F, Davis PJ, Habib AS, et al. Society for ambulatory anesthesia guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1615–28. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000295230.55439.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gold BS, Kitz DS, Lecky JH, Neuhaus JM. Unanticipated admission to the hospital following ambulatory surgery. JAMA. 1989;262:3008–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kranke P, Morin AM, Roewer N, Wulf H, Eberhart LH. The efficacy and safety of transdermal scopolamine for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:133–43. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200207000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey PL, Streisand JB, Pace NL, Bubbers SJ, East KA, Mulder S, et al. Transdermal scopolamine reduces nausea and vomiting after outpatient laparoscopy. Anesthesiology. 2002;72:977–80. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199006000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kranke P, Morin AM, Roewer N, Eberhart LH. Dimenhydrinate for prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:238–44. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.t01-1-460303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parlow JL, Meikle AT, Vlymen J, Avery N. Postdischarge nausea and vomiting after ambulatory laparoscopy is not reduced by promethazine prophylaxis. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46:719–24. doi: 10.1007/BF03013905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Büttner M, Walder B, von Elm E, Tramèr MR. Is low-dose haloperidol a useful antiemetic.: A meta-analysis of published and unpublished randomized trials? Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1454–63. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200412000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domino KB, Anderson EA, Polissar NL, Posner KL. Comparative efficacy and safety of ondansetron, droperidol, and metoclopramide for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting: A meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1370–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199906000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan GE, Mikhail MS, Murray MJ. Clinical Anesthesiology: Adjuncts to anesthesia. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002. pp. 242–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hesketh PJ, Gandara DR. Serotonin antagonists: A new class of antiemetic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:613–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.9.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tramer MR, Moore RA, Reynolds DJ, McQuay HJ. A quantitative systematic review of ondansetron in the treatment established postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1277–89. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7087.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polati E, Verlato G, Finco G, Mosaner W, Grosso S, Gottin L, et al. Ondansetron verus metoclopramide in the treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:395–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199708000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paxton DL, Mckay CA, Mirakin KR. Prevention of nausea and vomiting after day case gynaecological laparoscopy. A comparison of ondansetron, droperidol, metoclopramide and placebo. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:403–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb05993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langner E, Greifenberg S, Gruenwald J. Ginger: History and use. Adv Ther. 1998;15:25–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan JL, Heckler CE, Roscoe JA, Dakhil SR, Kirshner J, Flynn PJ, et al. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) reduces acute chemotherapy-induced nausea: A URCC CCOP study of 576 patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1479–89. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1236-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panahi Y, Saadat A, Sahebkar A, Hashemian F, Taghikhani M, Abolhasani E. Effect of ginger on acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A pilot, randomized, open-label clinical trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:204–11. doi: 10.1177/1534735411433201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lien HC, Sun WM, Chen YH, Kim H, Hasler W, Owyang C. Effects of ginger on motion sickness and gastric slow-wave dysrhythmias induced by circular vection. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G481–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00164.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bone M, Wilkinson DJ, Young JR, McNeil J, Charlton S. Ginger root-a new antiemetic, the effect of ginger root on postoperative nausea and vomiting after major gynecological surgery. Anesthesia. 1990;45:669–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1990.tb14395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaiyakunapruk N, Kitikannakorn N, Nathisuwan S, Leeprakobboon K, Leelasettagool C. The efficacy of ginger for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:95–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pongprojpaw D, Chiamchanya C. The effcacy of ginger in prevention of post-operative nausea and vomiting after outpatient gynecological laparoscopy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86:244–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamahara JR, Iwamoto M, Kobayashi G, Mutsuda H, Fujimura H. Active components of ginger exhibiting antiserotoninergic action. Phytother Res. 1989;3:70–1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lumb AB. Mechanism of antiemetic effect of ginger. Anesthesia. 1993;48:1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb07572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellville JW, Bross ID, Howlans WS. A method for the clinical evaluation of antiemetic agents. Anesthesiology. 1959;20:753–60. doi: 10.1097/00000542-195911000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boothe P, Finegan BA. Changing the admission process for elective surgery: An economic analysis. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:391–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03015483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee A, Gin T, Lau AS, Ng FF. A comparison of patients' and health care professionals' preferences for symptoms during immediate postoperative recovery and the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:87–93. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000140782.04973.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gan TJ. Risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1884–98. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000219597.16143.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryer E. A literature review of the effectiveness of ginger in alleviating mild-to-moderate nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50:e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pertz HH, Lehmann J, Roth-Ehrang R, Elz S. Effects of ginger constituents on the gastrointestinal tract: Role of cholinergic M3 and serotonergic 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors. Planta Med. 2011;77:973–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Apariman S, Ratchanon S, Wiriyasirivej B. Effectiveness of ginger for prevention of nausea and vomiting after gynecological laparoscopy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89:2003–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips S, Ruggier R, Hutchinson SE. Zingiber officinale (ginger) – An antiemetic for day case surgery. Anaesthesia. 1993;48:715–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb07188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eberhart LH, Mayer R, Betz O, Tsolakidis S, Hilpert W, Morin AM, et al. Ginger does not prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic surgery. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:995–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000055818.64084.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visalyaputra S, Petchpaisit N, Somcharoen K, Choavaratana S. The efficacy of ginger root in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after outpatient gynaecological laparoscopy. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:506–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]