Abstract

Among 34 Spn sequential isolates from middle ear fluid we found a case of a nontypeable Streptococcus pneumoniae (NT-Spn) in a child with AOM. The strain was pneumolysin PCR positive and capsule gene PCR negative. Virulence of the NT-Spn was confirmed in a chinchilla model of AOM.

Keywords: multi-locus sequence typing, nontypeable Streptococcus pneumoniae, acute otitis media

1. Introduction

Virtually all Streptococcus pneumoniae (Spn) causing acute otitis media (AOM) and sinusitis are encapsulated (Hanage et al.; 2006; Kadioglu et al., 2008). Non-typeable Streptococcus pneumoniae (NT-Spn) have generally been viewed as an organism that does not cause suppurative infections; they have typically been described as pathogens in epidemic bacterial conjunctivitis (Barker et al., 1999; Medeiros et al., 1998; Carvalho et al., 2003; Martin et al., 2003; Berron et al., 2005; Hanage et al., 2006; Porat et al., 2006; Williamson et al., 2008) although one paper described NT-Spn as a cause of invasive pneumoccal disease (Lacapa R etet al, 2006). Recently we isolated a NT-Spn from MEF of a child with suppurative AOM in Rochester, New York. This case report describes the suppurative AOM case and the characterization of the strain, including its genetic background and genetic relatedness to other Spn isolates, and its virulence in an experimental chinchilla model of AOM.

2. Case Report

A 7-month-old male developed an apparent upper respiratory viral infection followed 2 days later by fever of 39 Centigrade, and symptoms of an AOM. On examination the tympanic membranes were bulging and erythematous with a purulent effusion bilaterally. The remainder of the examination included coryza and an absence of conjunctival injection or drainage. Since the child had enrolled in a prospective study sponsored by the NIH, NIDCD that called for a tympanocentesis whenever AOM occurred, the procedure was performed and produced copious purulent material from behind both tympanic membranes that later grew a NT-Spn (Pichichero et al., 2006). A culture from the nose and throat was also obtained per the study protocol and the nose culture grew the same NT-Spn. The child was treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate at a dose of 80 mg/Kg/day divided twice daily for 5 days and recovered uneventfully. He had two subsequent AOM infections where nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae was isolated. Thereafter he remained well with no further AOMs or other significant respiratory infections.

The bacterial isolates from MEF and nasopharyngeal were identified as Spn by tests were according to the 8th edition of Manual of Clinic Microbiology (Ruoff et al., 2003). Serotyping on both isolates was negative as determined by latex agglutination (Pneumotest-Latex, Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark). Both isolates were susceptible to optochin as tested using a Taxo P Disc (BD diagnostic Systems) and were bile soluble (Table 1).

Table 1.

Nontypeable S. pneumoniae strain ST448

| Strain | MLST Type |

Sera type |

Optochin (mm) |

Bile test |

CpsA PCR |

Ply PCR |

Allele number of house keep genes |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aroE | gdh | gki | recP | spi | xpt | ddl | |||||||

| 0702064AOM1MEF | ST448 | NT | + (22) | + | − | + | 8 | 5 | 2 | 27 | 2 | 11 | 71 |

| 0702064AOM1NP | ST448 | NT | + (24) | + | − | + | 8 | 5 | 2 | 27 | 2 | 11 | 71 |

To further confirm the strain was a Spn, bacterial genomic DNA was extracted to amplify the pneumolysin (gly)gene by PCR using forward primer CCCACTCTTCTTGCGGTTGA and reverse primer TGAGCCGTTATTTTTTCATACTG, with a annealing temperature 55 °C (Murdoch et al., 2003). The strain from both the MEF and NP specimens expressed pneumolysin (Table 1). To determine that the strain did not have a capsule gene (cps) locus, the conserved capsular gene dexB (1714-3485 of GenBank Z47210) was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA using forward primer ATCCTTGTCAGCTCTGTGTC and reverse primer TCACTTGCAACTACATGAAC, with a with an annealing temperature of 50°C (Hanage et al 2006). An encapsulated strain with serotype 3 was used as a positive control. Both isolates from the MEF and NP specimens were PCR negative for capsule gene (Table 1), confirming that the isolate did not contain cps locus.

MICs of the NT-Spn isolates to 13 antibiotics were determined by broth microdilution (BMD) method according to CLSI (M100-S20). The isolates from MEF and NP were susceptible to all tested antibiotics including penicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin, cefdinir, cefpodoxime, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, faropenem, azithromycin, telithromycin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin and trimethoprim.

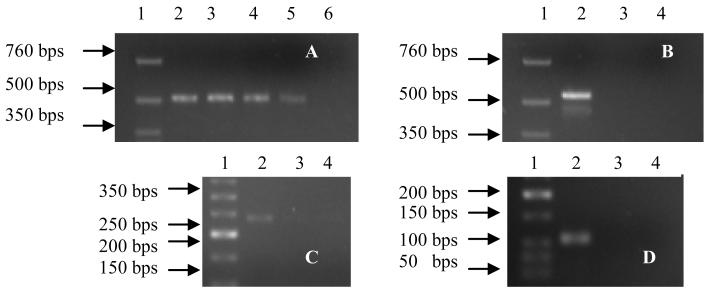

To prove that the NT-Spn was the sole otopathogen, multiplex PCR (mPCR) was applied to detect DNA of 16S rRNA gene of Haemophilus influenza(Hflu)e, Moraxella catarrhalis (Mcat) and Streptococcus pyogenes (Pyo) in the MEF as previously described (Hendolin et al., 1997) except reactions for each bacterial were separated in different tubes to avoid mutual interference. The mPCR was positive for Spn, but negative for the other bacteria in the MEF (Figure 1), indicating the NT-Spn was only pathogen causing AOM in this case.

Figure 1.

Only Spn but Hflu, Mcat and Spyo was detected in MEF by multiplex PCR. DNA was extracted from MEF and nasal wash samples, NT-Spn isolates and positive control strain to amplify Spn (panel A), Hflu (panel B), C Mcat (panel C) and Spyo (panel D). PCR products size was evaluated on 2% agarose gel. Panel A, PCR for Spn, lane 1, DNA ladder; Lane 2, positive control; Lane 3, NT-Spn isolate from NP (0702064AOM1NP); Lane 4,NT-Spn Isolate from MEF (0702064AOM1MEF); lane 5, MEF samples; lane 6, negative control. Panel B-D, PCR for Hflu, Mcat and Spyo, lane 1, DNA ladder; Lane 2, positive control; Lane 3, DNA from MEF; lane 4, negative control.

Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) was performed to characterize the NT-Spn strain as described previously (Enright and Spratt, 1998) and in the Spn MLST database (http://spneumoniae.mlst.net/). The sequence type of the NT-Spn from both the MEF and NP specimens was the same, MLST 448 (Table 1). In order to illustrate nucleotide sequence divergence and explore the genetic relatedness of the NT-Spn isolate to other isolates, minimum evolution trees were constructed from the sequence of all seven alleles using the neighbor-joining method. The sequences of seven loci were concatenated to obtain a 3199-bps contigs and then a neighbor-joining tree was drawn using MEGA 4.0 (Tamura et al., 2007). The genetic linkage distance of the NT-Spn strain described in this report was close to three other, new strains that were sequence types 22, 35 and 9/34/35/42/47 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Genetic relatedness (neighbor-joining tree) of the non-encapsulated strain of Spn described here with other isolates. Scale bar indicates number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

The virulence of the NT-Spn strain was evaluated in an experimental chinchilla model of AOM using two different previously described routes for middle ear challenge (Babl et al., 2002; Sabharwal et al., 2009). In an experiment of NP challenge followed by barotrauma, 2 chinchilla (4 ears) were challenged intranasally with 10E7 cfu of our NT-Spn strain in 100ul per nares. One day following challenge, NP colonization was present in both animals at 2×10E4 cfu/ml. None of 4 ears subsequently developed signs of experimental AOM and all four ears were culture negative when cultured 3 days following barotrauma. In an experiment of direct inoculation of the middle ear, 2 animals (four ears) were challenged directly with 52 cfu in 100 μl of HBSS of our NT-Spn strain. Two days following inoculation the right ear of one animal was culture positive (100cfu/ml); five days following inoculation the left ear of the same animal was culture positive (10E5 cfu / ml). Two additional chinchilla (4 additional ears) were challenged directly with 1000 cfu in 100 μl of HBSS of the NT-Spn strain. All four had culture positive middle ear disease present at 3 days following challenge (1,000 cfu per ml).

3. Discussion

This case report of suppurative AOM in a child caused by NT-Spn is the first, to our knowledge, to be confirmed in the US as a sole otopathogen.

Up to now, there have been 320 nontypeable Spn isolates with 205 sequence types registered into MLST database. Of them, 27 isolates with 10 sequence types were isolated from AOM cases, but most sequence types were from the nasopharynx. Only ST448(ours) and ST13 (Lipsitch M 2007) were from MEF (Lipsitch et al., 2007). Lipsitch et al (2007) did not provide any clinical information about the ST13 strain nor did they exhaustively characterize the strain as we have. In 2005 and 2006, Hanage WP et al found three NT-Spn strains with STs 448, 449 and 344 from the MEF of Finnish children with AOM (Hanage et al., 2005; Hanage et al., 2006). Their strains were not included in the MLST database. Neither Lipsitch et al (2007) nor Hanage et al. (2005, 2006). mentioned if any other otopathogens were involved in the AOM.

The ST448 seems to be an international strain that broadly causes conjunctivitis (Porat et al., 2006), and has begun to associate with AOM (Hanage et al., 2006). There are 17 isolates reported to MLST database that are nonserotypeable Spn from 8 countries (Australia, China, Germany, Portugal, Switzerland, Thailand, UK, USA) (Hathaway et al., 2004; Porat et al., 2006; Lipsitch et al., 2007; Sá-Leão et al., 2006). Nine of 17 ST448 isolates in the MLST database are resistant to at least one of five antibiotics (penicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, chloramphenciol, cefotaxime). In genetic relatedness, ST448 is most close to other five STs (1229, 1290, 3064, 3065 and 4141) that were non nonserotypeable and two STs (3278, 3283) that were serotype 6A and 7C. ST448 differs from these strains in only one of seven loci. Among three major nonserotypeable strains (STs 344,448,449) from middle ear fluid, ST 448 does not cluster with STs 344 and 449 (Hanage et al., 2006), while ST 344 and ST449 differ only in one of seven loci (ddl). ST448 has only one same locus as STs 499 and 344.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by NIH, NIDCD RO1DC008671-01A2 and the Thrasher Research Fund (Salt Lake, Utah) award # 02823-2 and by an investigator-initiated research grant from Wyeth. Pharmaceuticals (Collegeville, PA) (all to M.E. Pichichero). The authors gratefully acknowledge the staff of Legacy Pediatrics for sample collection. We also thank Diana G. Adlowitz and Denmark Statens Serum Institute for assistance with culture and serotyping.

References

- 1.Babl FE, Pelton SI, Li Z. Experimental acute otitis media due to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: comparison of high and low azithromycin doses with placebo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2194–2199. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2194-2199.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker JH, Musher DM, Silberman R, Phan HM, Watson DA. Genetic relatedness among nontypeable pneumococci implicated in sporadic cases of conjunctivitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:4039–4041. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.4039-4041.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berron S, Fenoll A, Ortega M, Arellano N, Casal J. Analysis of the genetic structure of nontypeable pneumococcal strains isolated from conjunctiva. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;2005;43:1694–1698. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1694-1698.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvalho MG, Steigerwalt AG, Thompson T, Jackson D, Facklam RR. Confirmation of nontypeable Streptococcus pneumoniae-like organisms isolated from outbreaks of epidemic conjunctivitis as Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;2003;41:4415–4417. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.9.4415-4417.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . CLSI; Wayne, PA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enright MC, Spratt BG. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt 11):3049–3060. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanage WP, Kaijalainen T, Herva E, Saukkoriipi A, Syrjanen R, Spratt BG. Using multilocus sequence data to define the pneumococcus. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:6223–6230. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.17.6223-6230.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanage WP, Kaijalainen T, Saukkoriipi A, Rickcord JL, Spratt BG. A successful, diverse disease-associated lineage of nontypeable pneumococci that has lost the capsular biosynthesis locus. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:743–749. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.743-749.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendolin PH, Markkanen A, Ylikoski J, Wahlfors JJ. Use of multiplex PCR for simultaneous detection of four bacterial species in middle ear effusions. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2854–2858. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2854-2858.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadioglu A, Weiser JN, Paton JC, Andrew PW. The role of Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors in host respiratory colonization and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:288–301. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacapa R, Bliss SJ, Larzelere-Hinton F, Eagle KJ, McGinty DJ, Parkinson AJ, Santosham M, Craig MJ, O’Brien KL. Changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among White Mountain Apache persons in the era of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(4):476–84. doi: 10.1086/590001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipsitch M, O’Neill K, Cordy D, Bugalter B, Trzcinski K, Thompson CM, Goldstein R, Pelton S, Huot H, Bouchet V, Reid R, Santosham M, O’Brien KL. Strain characteristics of Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage and invasive disease isolates during a cluster-randomized clinical trial of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(8):1221–7. doi: 10.1086/521831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin M, Turco JH, Zegans ME, Facklam RR, Sodha S, Elliott JA, Pryor JH, Beall B, Erdman DD, Baumgartner YY, Sanchez PA, Schwartzman JD, Montero J, Schuchat A, Whitney CG. An outbreak of conjunctivitis due to atypical Streptococcus pneumoniae. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1112–1121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hathaway LJ, Stutzmann Meier P, Bättig P, Aebi S, Mühlemann K. A homologue of aliB is found in the capsule region of nonencapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(12):3721–9. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3721-3729.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medeiros MI, Neme SN, da Silva P, Silva JO, Carneiro AM, Carloni MC, Brandileone MC. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae as etiological agents of conjunctivitis outbreaks in the region of Ribeirao Preto, SP, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1998;1998;40:7–9. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46651998000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murdoch DR, Anderson TP, Beynon KA, Chua A, Fleming AM, Laing RT, Town GI, Mills GD, Chambers ST, Jennings LC. Evaluation of a PCR assay for detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae in respiratory and nonrespiratory samples from adults with community-acquired pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(1):63–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.63-66.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porat N, Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Shuval DS, Trefler R, Segev O, Hanage WP, Dagan R. The important role of nontypable Streptococcus pneumoniae international clones in acute conjunctivitis. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:689–696. doi: 10.1086/506453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruoff KL, Whiley RA, Beighton D. Streptococcus. In: Murray PR, Barron EJ, Pfaller MA, Jorgensen JH, Yolken RH, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 8th ed. American Society for Microbiology; Washington, D.C.: 2003. pp. 405–421. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabharwal V, Ram S, Figueira M, Park IH, Pelton SI. Role of complement in host defense against pneumococcal otitis media. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1121–1127. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01148-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sá-Leão R, Simões AS, Nunes S, Sousa NG, Frazão N, de Lencastre H. Identification, prevalence and population structure of non-typable Streptococcus pneumoniae in carriage samples isolated from preschoolers attending day-care centres. Microbiology. 2006;152(Pt 2):367–76. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28596-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williamson YM, Gowrisankar R, Longo DL, Facklam R, Gipson IK, Ades EP, Carlone GM, Sampson JS. Adherence of nontypeable Streptococcus pneumoniae to human conjunctival epithelial cells. Microb Pathog. 2008;44:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]