Abstract

Nitro-oleic acid (OA-NO2), an electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkene byproduct of redox reactions, activates transient receptor potential ion channels (TRPA1 and TRPV1) in primary sensory neurons. To test the possibility that signaling actions of OA-NO2 might modulate TRP channels, we examined: (1) interactions between OA-NO2 and other agonists for TRPA1 (allyl-isothiocyanate, AITC) and TRPV1 (capsaicin) in rat dissociated dorsal root ganglion cells using Ca2+ imaging and patch clamp techniques and (2) interactions between these agents on sensory nerves in the rat hindpaw. Ca2+ imaging revealed that brief application (15-30 sec) of each of the three agonists induced homologous desensitization. Heterologous desensitization also occurred when one agonist was applied prior to another agonist. OA-NO2 was more effective in desensitizing the response to AITC than the response to capsaicin. Prolonged exposure to OA-NO2 (20 min) had a similar desensitizing effect on AITC or capsaicin. Homologous and heterologous desensitization were also demonstrated with patch clamp recording. Deltamethrin, a phosphatase inhibitor, reduced the capsaicin or AITC induced desensitization of OA-NO2 but did not suppress the OA-NO2 induced desensitization of AITC or capsaicin, indicating that heterologous desensitization induced by either capsaicin or AITC occurs by a different mechanism than the desensitization produced by OA-NO2. Subcutaneous injection of OA-NO2 (2.5 mM, 35 μL) into a rat hindpaw induced delayed and prolonged nociceptive behavior. Homologous desensitization occurred with AITC and capsaicin when applied at 15 minute intervals, but did not occur with OA-NO2 when applied at a 30 min interval. Pretreatment with OA-NO2 reduced AITC-evoked nociceptive behaviors but did not alter capsaicin responses. These results raise the possibility that OA-NO2 might be useful clinically to reduce neurogenic inflammation and certain types of painful sensations by desensitizing TRPA1 expressing nociceptive afferents.

Keywords: desensitization, nociception, nitro-oleic acid, primary sensory neuron, TRP channels

Introduction

Nitro-oleic acid (OA-NO2) and related nitroalkenes are electrophilic fatty acid derivatives formed by nitric oxide- or nitrite-mediated redox reactions. These species are present in normal tissues at nM concentrations and can increase during inflammation to almost μM concentrations (Baker et al., 2005; Batthyany et al., 2006; Bonacci et al., 2012). Fatty acid nitroalkenes induce a variety of pharmacological effects including: (1) activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) (Baker et al., 2005), (2) activation of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway (Villacorta et al., 2007), (3) upregulation of heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) expression (Wright et al., 2006), (4) inhibition of NF-κB-dependent gene expression (Cui et al., 2006; Villacorta et al., 2013), (5) inhibition of platelet or neutrophil function and (6) inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine secretion by macrophages (Coles et al., 2002a; Coles et al., 2002b). These actions can all be ascribed to the post-translational modification of functionally significant proteins by the reversible Michael addition reactions that nitroalkenes can undergo. OA-NO2 may thus function as an endogenous anti-inflammatory mediator and contribute to resolution of inflammation (Schopfer et al., 2011).

OA-NO2 also activates TRPA1 and TRPV1, which are nonselective cation channels expressed in nociceptive primary sensory neurons (Sculptoreanu et al., 2010; Taylor-Clark et al., 2009). Sensitization of these channels is involved in the development of hyperalgesia (hypersensitivity to noxious stimuli) in inflammatory pain models (da Costa et al., 2010; Davis et al., 2000); while desensitization is an important mechanism for down-regulation of channel activity and reducing nociceptor function. Capsaicin, a specific TRPV1 agonist, activates and subsequently desensitizes TRPV1 channels (homologous desensitization) and also reduces the effect of allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) on TRPA1 channels (heterologous desensitization) (Ruparel et al., 2008; Salas et al., 2009). AITC elicits similar homologous and heterologous (TRPV1) desensitization (Ruparel et al., 2008; Salas et al., 2009).

The present experiments used Ca2+ imaging and patch clamp techniques to examine: (1) desensitizing interactions between OA-NO2, capsaicin and AITC in dissociated dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons of adult rats and (2) the interactions between these agents on sensory nerves in the rat hind paw. Our results revealed that pretreatment with OA-NO2 desensitized TRPA1 and TRPV1 responses in vitro as well as the TRPA1 response in vivo. These findings raise the possibility that anti-inflammatory signaling actions of OA-NO2 can also be related in part to modulation of TRP channels in sensory neurons. This suggests that electrophilic fatty acids such as OA-NO2 might be clinically useful in reducing neurogenic inflammation and certain types of painful sensations by desensitizing nociceptive afferents.

Materials and Methods

Experiments were performed on adult Sprague-Dawley female rats (200-250g). The stage of the estrous cycle at the time of the experiments was not determined. All experimental protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol approval # IACUC 1201539) and were consistent with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the International Association for the Study of Pain.

DRG neuron culture

After a laminectomy under isoflurane anesthesia L4 - L6 DRGs were removed bilaterally, enzymatically treated (collagenase type 4, 2mg/ml and trypsin, 1mg/ml; Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) and mechanically dissociated as described elsewhere (Zhang et al., 2011). The cells were plated on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 90% humidity for at least 3-4 h before Ca2+ imaging or patch clamp recording. Because trypsin treatment has been reported to reduce TRPA1 responses, cells were studied 4-12 hours after dissociation to allow for recovery from the effects of dissociation. The percentage of AITC responsive neurons obtained in our Ca2+ imaging (33%) and patch clamp recording (43%) were comparable with the percentages reported in other studies (Dai et al., 2007; Kobayashi et al., 2005) suggesting that this time period is sufficient for return of TRPA1 responses.

Ca2+ imaging

DRG cells were loaded with Fura 2-AM (2 μM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 min at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Fura 2-AM was dissolved in Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing (in mM): 138 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.3 KH2PO4, 4 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 5.6 glucose, pH 7.4. Ca2+ imaging was performed as previously (Zhang et al., 2011). Briefly, coverslips were placed on an epifluorescence microscope (Olympus IX70) and continuously perfused (2–3 ml/min) with HBSS. Fura 2 was excited alternately with ultraviolet light at 340 and 380 nm; and the fluorescence emission was detected at 510 nm using a computer-controlled monochromator. Image pairs were acquired every 1–30 s using illumination periods between 20 and 50 ms. Wavelength selection, timing of excitation, and the acquisition of images were controlled using the program C-Imaging (Compix, Cranberry Township, PA) running on a personal computer. Digital images were stored on hard disk for off-line analysis. One coverslip usually contained 20–40 DRG neurons/microscopic field at 40X magnification. OA-NO2 was synthesized as described previously (Baker et al., 2004). Capsaicin and allyl-isothiocyanate (AITC) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). On the day of the experiment, stock solutions of OA-NO2 (70 mM in 100 % ethanol), capsaicin (10 mM in 100% ethanol) and AITC (100 mM in DMSO) were diluted in HBSS and delivered via bath application using a gravity-driven system (infusion rate was 2-3 ml/min). Vehicles applied via the same method were inactive.

Patch clamp recording

Voltage-clamp data were acquired with conventional whole cell patch clamp techniques with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale CA) controlled with a PC running pClamp Software (V 10.3, Molecular Devices). Current traces were sampled at 5-10 kHz and filtered at 1-2 kHz. Patch electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass (WPI, Sarasota FL) on a horizontal puller (Sutter Inst. Novato CA), and had resistances of 2-5 MΩ when filled with an electrode solution containing (in mM): K-methanesulfonate 110, KCl 30, NaCl 5, CaCl2 1, MgCl2 2, HEPES 10, EGTA 11, Mg-ATP 2, Li-GTP 1, pH 7.2 (adjusted with Tris-base), 310 mOsm (adjusted with sucrose). Currents were recorded in HBSS solution. The junction potential associated with all test solutions was measured and was less than 5 mV, and therefore, junction potential was not corrected. Series resistance compensation was >80%. Whole-cell capacitance and series resistance were compensated with amplifier circuitry. Neurons were held at −60 mV and OA-NO2, capsaicin and AITC were applied with a piezo- driven perfusion system (Warner Instruments, Hamden CT). Current data were analyzed with pClamp software in combination with SigmaPlot (Systat, Chicago, IL). Current density was determined by dividing peak-evoked current by membrane capacitance (as determined with a 5 mV voltage step prior to compensation).

Behavioral tests

On the day of experiments, stock solutions of chemicals: capsaicin (10 mM in 100% ethanol), AITC (1 M in DMSO) and OA-NO2 (70 mM in 100% ethanol) were diluted with normal saline. The concentrations of all agents used in vivo were 100 times higher than those tested in vitro on DRG neurons. Rats were put in a transparent box at least 30 min before behavioral testing. Then 35 μL of capsaicin (100 μM), AITC (10 mM) or OA-NO2 (2.5 mM) or a vehicle control was injected subcutaneously into the plantar surface of the right hand paw. The concentrations and the amounts of injected capsaicin and AITC were similar to those used in other behavioral studies (Ruparel et al., 2008; Schmidt et al., 2009). The nociceptive responses were measured for 20-30 min by an observer blinded to treatments by counting the time spent licking or withdrawing the hindpaw during 5 min periods post-injection. For homologous or heterologous desensitization experiments, 10-30 min after the first injection the rats received a second injection (35 μL) at the same site as the first injection and the behavioral test was repeated.

Data analysis

In Ca2+ imaging studies, data were analyzed using program C-Imaging (Compix). Background was subtracted to minimize camera dark noise and tissue autofluorescence. An area of interest was drawn around each cell, and the average value of all pixels included in this area was taken as one measurement. The ratio of fluorescence signal measured at 340 nm divided by the fluorescence signal measured at 380 nm was used to measure the increase of intracellular Ca2+. All data are expressed as Mean ± SEM. Paired or unpaired t-test or one way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test were used to assess statistical significance. Chi square tests were used when % responsive neurons was compared, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of OA-NO2, AITC and capsaicin induced Ca2+ transients

Concentrations of the three agonists (15 or 30 μM for OA-NO2, 100 μM for AITC and 500 nM for capsaicin) were selected based on our previous study and reports in literature to be near the concentrations for eliciting maximal TRPA1 or TRPV1 activation (Caterina et al., 1997; Macpherson et al., 2007; Sculptoreanu et al., 2010). In agreement with our previous study (Sculptoreanu et al., 2010) and another study (Taylor-Clark et al., 2009), the neurons responsive to the three agents were small to medium size (20 to 35 μm). Data from 8 rats indicated that most of the OA-NO2-responsive neurons were AITC sensitive (95%) or capsaicin sensitive (80%), and most of the AITC sensitive neurons (93%) were capsaicin sensitive. Capsaicin elicited the largest increase in Ca2+ in the highest percentage (70.5%) of DRG neurons (Fig. 1 and Table 1); whereas, OA-NO2 and AITC elicited similar amplitude Ca2+ signals in a similar percentage of DRG neurons (35% for OA-NO2 and 33% for AITC) (Fig.1 and Table 1). OA-NO2 and AITC elicited Ca2+ transients with similar latencies (measured from time of application to the onset of the response) and times to peak that were longer than capsaicin-induced Ca2+ transients (p< 0.01, Table 1). The decay phase of the capsaicin-induced Ca2+ response usually had two components; a fast decay phase followed by a slow phase, while OA-NO2 and AITC responses usually did not have a prominent fast component, and required longer to decay to half of the peak amplitude (p<0.05) (Fig.1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of OA-NO2 (O-N), AITC (AI) and capsaicin (Cap) induced intracellular Ca2+ transients in dissociated DRG neurons. O-N 30 μM (A) or AI 100 μM (B) was applied for 30 sec; Cap 500 nM (C) was applied for 15 sec (indicated by arrows). Ca2+ increase is expressed as the ratio of fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm (F340/F380). Scales are the same for all the traces. Each trace was obtained by averaging several cell responses from the same coverslip (n=6 cells for O-N, n=9 cells for AI, and n=11 cells for Cap). O-N and AI elicited Ca2+ transients having comparable kinetics, both of which had a smaller peak, a slower rate of rise and a slower rate of decay than the rate of the Cap transient. The decay phase of the Cap transient usually had two components, consisting of a fast component followed by a slow component, while the decay of O-N or AI responses was usually monophasic without the prominent fast component.

Table 1.

Comparison of OA-NO2 (O-N), AITC (AI) and Capsaicin (Cap) induced Ca2+ transients

| % of responsive neurons | Peak (ΔF340/F380) | Response latency (min) | Time from onset to peak (min) | Time for half decay from the peak (min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-N | 35.5 (n=1486) | 0.74 + 0.01 (n=282) ** | 1.07 + 0.11(n=28)** | 0.96 + 0.07 (n=116)** | 5.72 + 0.27 (n=87)* |

| AI | 33.4 (n=1057) | 0.69 ±0.02 (n=313)** | 1.05 ± 0.05(n=37)** | 0.45 + 0.02 (n=111)* | 5.59 0.31(n=95)* |

| Cap | 70.5 (n=925) | 0.94 + 0.01 (n=606) | 0.46 + 0.02(n=69) | 0.33 + 0.02 (n=186) | 4.74 + 0.27(n=160) |

Peak of transient (peak-baseline); response latency (time required from application to start of response, does not include the time required for the agent to pass through the perfusion system), n is cell number tested in each group. For response latency measurement, all cells were from an experiment on the same day to reduce the influence of variations in perfusion rate. For other parameters cells were from experiments performed on several days.

p<0.01

p<0.05 compared with Cap response

Phosphatase dependence of homologous desensitization

To evaluate homologous desensitization using Ca2+ imaging the same agent was applied two times at a 10 min interval (Fig.2). During this interval, the responses to the first application decayed substantially but often not completely (average to 10%-20% of the peak response). The ratio of second peak to the first peak was used as a measurement of desensitization. In agreement with other reports (Ruparel et al., 2008), we observed homologous desensitization of the capsaicin response in 90% of the neurons (164/182, 4 rats) (Fig.2C) and desensitization of the AITC response in 60% of the neurons (105/174, 4 rats) (Fig.2B). A potentiation (i.e., a second response that was larger than first one) was detected in 10% of capsaicin responsive neurons as described previously (Zhang et al., 2011) and in 40% of AITC responsive neurons. Homologous desensitization of OA-NO2 was detected in 90% of neurons (177/197, 4 rats) (Fig.2A); and potentiation occurred in the remaining 10% of neurons. The average magnitude of potentiation, measured as the ratio of the peak amplitudes of the second response to the first response, was small (capsaicin 20% increase, AITC 25% increase and OA-NO2 10% increase) and not studied further. The average magnitude of desensitization, measured in the same way, was large but varied between the three agonists. OA-NO2 and capsaicin elicited desensitization of similar magnitudes (58-62% decline in the second response); while AITC elicited a significantly smaller desensitization (20% reduction) (Fig. 2; Table 2).

Figure 2.

Homologous desensitization of OA-NO2 (O-N), AITC (AI) and capsaicin (Cap) induced intracellular Ca2+ responses in dissociated DRG neurons and the role of phosphatase. Tracings show typical responses to two applications of O-N (A), AI (B) and Cap (C) at 10 min intervals (indicated by arrows). Homologous desensitization during which the second response was smaller than the first was obvious for all three agents. The data are summarized in D-F as the ratio of second peak to the first peak. The magnitude of homologous desensitization for AI (E) was smaller compared to that for O-N (D) or Cap (F). Application of deltamethrin ( DM, 1 M) a phosphatase inhibitor immediately after the first application significantly reduced the homologous desensitization induced by Cap (F) but not by O-N (D) or AI (E). **: p < 0.01. The number above each bar represents the number of cells tested in each group. The left scale applies to A and B and the right scale applies to C.

Table 2.

Comparison of homologous desensitizations

| Ratio (second /first peak) for all cells | Ratio (second /first peak) for only desensitizing cells | % of neurons exhibiting potentiation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-N | 0.46 + 0.03 (n=197)* | 0.32 ± 0.02 (n=177)* | 10 (20/197) |

| AI | 1.22 + 0.10 (n=174) | 0.50 ± 0.03 (n=105) | 40 (69/174) |

| Cap | 0.39 + 0.02 (n=182)* | 0.32 ± 0.02 (n=164)* | 10 (18/182) |

Comparison of the magnitude of homologous desensitization after two applications of OA-NO2 (O-N), AITC (AI) and capsaicin (Cap) expressed as the ratio of the amplitude of second to first calcium transients in all cells responding to each agonist or this ratio only in cells exhibiting desensitization. The right column shows the percentage of neurons exhibiting homologous potentiation.

p<0.05, significantly different than the AI response.

The role of phosphatase in homologous desensitization was evaluated by administering deltamethrin (1 μM), a phosphatase inhibitor, beginning immediately after the peak of the first response until the second application of the agonist. In agreement with previous studies where desensitization was examined using patch clamp recording, measurement of neuropeptide release or in vivo behavioral assessments (Ruparel et al., 2008; Salas et al., 2009), homologous desensitization elicited by capsaicin (Fig.2F) but not by AITC (Fig.2E) was significantly reduced by blocking phosphatase activity with deltamethrin (Table 3). Homologous desensitization elicited by OA-NO2 was also not affected by application of deltamethrin (Fig.2D, Table 3). Application of deltamethrin increased the number of cells exhibiting capsaicin potentiation (from 10% increased to 20%), but did not alter the potentiation elicited by AITC or OA-NO2.

Table 3.

Summary of phosphatase dependence of the homologous and heterologous desensitization.

| Ligand interaction | Phosphatase dependence |

|---|---|

| O-N to O-N | no |

| O-N to Cap | no |

| O-N to AI | no |

| AI to AI | no |

| Cap to AI | no |

| AI to O-N | yes |

| AI to Cap | yes |

| Cap to Cap | yes |

| Cap to O-N | yes |

Phosphatase dependence of heterologous desensitization

To examine heterologous desensitization, the conditioning agonist was always applied 10 min before the test agonist and two parameters were measured: the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient (difference between baseline and peak) and the percentage of responsive neurons.

Heterologous desensitization between OA-NO2 and AITC

Reciprocal heterologous desensitization between OA-NO2 and AITC was tested on DRG cells from 3 rats (Fig.3). When AITC was applied first, the amplitude of OA-NO2 induced Ca2+ transients was significantly reduced (Fig.3A and 3B) as was the percentage of OA-NO2 responsive neurons (Fig. 3C). Conversely, OA-NO2 applied first decreased the amplitude of AITC induced Ca2+ transients (Fig 3D and 3E) as well as the percentage of AITC responsive neurons (3F). The magnitude of the AITC induced desensitization was greater than that induced by OA-NO2 when measured as the decrease in the percentage of responsive cells (66% vs. 42% decrease) or as the decrease in the peak amplitude of the responses (78% vs. 41% decrease in amplitude). Deltamethrin significantly reduced (p<0.05) the desensitization of the OA-NO2 response by AITC (Fig.3B and 3C), but did not alter the desensitization of the AITC response by OA-NO2 (Fig. 3E and 3F).

Figure 3.

Heterologous desensitization between AITC (AI) and OA-NO2 (O-N) and the role of phosphatase. Desensitization of O-N by prior application of AI is illustrated in A-C. (A) Typical recording from one DRG neuron that was responsive to both AI and O-N. O-N was applied 10 min after AI. The amplitude (difference between peak and baseline) of the O-N response (B) and the % of O-N responsive neurons (C) were significantly reduced after AI pretreatment compared to the responses when O-N was applied first (p<0.01 for amplitude, p<0.01 for % of responsive neurons). Application of 1 μM deltamethrin (DM) significantly attenuated the desensitization of O-N by AI (B and C). Desensitization of AI by O-N is illustrated in D-F. (D) Typical recording from one neuron that was responsive to both O-N and AI, AITC was applied 10 min after application of O-N. The amplitude (difference between peak and baseline) of AI responses (E) and % of AI responsive neurons (F) were significantly reduced after O-N treatment compared to the responses when AI was applied first (p<0.001 for amplitude, p<0.01 for % of responsive neuron). Application of 1 μM DM did not affect the desensitization of AI by O-N (E and F). The number above each bar is the number of cells tested in each group. NS: no significant difference (p>0.05).

Heterologous desensitization between OA-NO2 and capsaicin

Reciprocal heterologous desensitization between OA-NO2 and capsaicin was tested on DRG cells from 3 rats. When capsaicin was applied first, the neurons were unresponsive to OA-NO2 (Fig.4A, B and C). When OA-NO2 was applied first the percentage of capsaicin responsive neurons (4F) as well as the peak amplitude of capsaicin induced Ca2+ transients (Fig.4D and 4E) were significantly reduced (39.6% decrease in the percentage of responsive neurons and 45% decrease in peak amplitude). The desensitization of OA-NO2 by capsaicin was significantly larger (p<0.05) than the desensitization of capsaicin by OA-NO2. Deltamethrin reduced the capsaicin induced desensitization of the OA-NO2 response (Fig.4B and 4C), but did not alter the OA-NO2 desensitization of the capsaicin response (Fig.4E and 4F).

Figure 4.

Heterologous desensitization between capsaicin (Cap) and OA-NO2 (O-N) and the role of phosphatase. Desensitization of O-N by Cap is illustrated in figures A-C. (A) a typical trace from one DRG neuron in which the response to O-N was absent 10 minutes after prior application of Cap. In all 72 Cap sensitive neurons from 2 rats, the response to O-N was absent after pretreatment with Cap (B and C). Application of 1 μM deltamethrin (DM) significantly attenuated the desensitization of O-N by Cap (B and C). Desensitization of Cap by O-N is shown in figures D-F. (D) typical responses of two groups of neurons from the same coverslip where Cap was applied 10 min after O-N. One group of neurons was sensitive to both O-N and Cap (solid trace), and the second group of neurons was sensitive to Cap but not O-N (dashed trace). Each trace represents the average of responses of 6 neurons, a significant reduction of Cap response after O-N was observed for the first group neurons, (error bars were omitted for clear demonstration). (E) Compared with the amplitude of the Cap responses measured in the population of neurons that were unresponsive to O-N, the amplitude of the Cap responses was significantly reduced (p<0.01) when administered after an application of O-N that increased Ca2+. Similarly, the % of Cap responsive neurons was decreased significantly (p<0.05) (F) when the neurons were pretreated with O-N. Application of 1 μM DM did not affect the desensitization of capsaicin by O-N (E and F, p>0.05). The number above each bar is the number of cells for each group. NS: no significant difference (p>0.05).

Heterologous desensitization between AITC and capsaicin

In agreement with other reports (Ruparel et al., 2008), heterologous desensitization between capsaicin and AITC responses was also detected. In DRG neurons from 3 rats, pretreatment with AITC significantly attenuated the capsaicin response, elicited a small decrease in the percentage of capsaicin responsive neurons (from 72% to 62.5%) and induced a large decrease (43%) in the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ signal (measured as the 340/380 nm ratio) from 0.855±0.02 (n=160) to 0.495±0.04 (n=89) (p<0.001). Conversely, pretreatment with capsaicin reduced the percentage of AITC responsive neurons from 33% to 12.5% and significantly decreased the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ transient from 0.701±0.02 (n=102) to 0.44±0.05 (n=54) (p<0.001). Consistent with other reports (Ruparel et al., 2008), pretreatment with deltamethrin (1 μM) significantly reduced the AITC desensitization of the capsaicin response (0.712±0.06, peak amplitude of capsaicin response after deltamethrin treatment, n=23, p<0.05), but did not alter the capsaicin-induced desensitization of the AITC response (n=14, p>0.05).

Heterologous desensitization elicited by prolonged exposure to OA-NO2

To mimic in vivo conditions in which OA-NO2 might be elevated above basal levels for prolonged periods, OA-NO2 (15 μM) was applied to DRG neurons for 20 min prior to the application of either AITC or capsaicin. When compared to the effects of a brief application of OA-NO2 the prolonged application produced a similar reduction in the percentage of cells responding to AITC (decrease >0.05, Fig.5F vs Fig.3F) and similar decrease in the peak amplitude of the AITC Ca2+ transient (p>0.05, Fig.5E vs Fig.3E) (n=2 rats). The prolonged and brief OA-NO2 applications also had similar desensitizing effects on the capsaicin responses (p>0.05, Fig.5C vs Fig.4F) (p>0.05, Fig.5B vs Fig.4E, n=2 rats).

Figure 5.

Prolonged incubation with OA-NO2 (O-N) desensitized capsaicin (Cap) and AITC (AI) responses. Desensitization of Cap responses by pretreatment with O-N for 20 min is shown in figures A-C. O-N responsive neurons were identified by a higher baseline (0.63±0.05, n=86) before Cap application than unresponsive neurons (0.24±0.02 n=53) (5A) (A) Solid trace is the averaged capsaicin responses from 6 O-N responsive neurons and dashed trace is the averaged capsaicin responses from 8 O-N unresponsive neurons from same coverslip. (B) The amplitude of the Cap transients in O-N responsive neurons was significantly smaller after O-N incubation, than the amplitude in O-N unresponsive neurons (summarized data from 2 rats). (C). O-N incubation did not change the % of Cap responsive neurons. Desensitization of AI responses by pretreatment with O-N for 20 min is shown in figures D-F. (D) Solid trace is the averaged AI response from 5 O-N responsive neurons after O-N incubation, and the dashed trace is the averaged AI response of 6 neurons from one coverslip without O-N pretreatment. (E) summarized data showing a significant reduction of AI responses after O-N pretreatment compared with AI responses without O-N pretreatment (p<0.001). (F) Summarized data showing a significant decrease in % of AI responsive neurons after O-N pretreatment (p<0.01). The number above each bar is the number of cells for each group.

Homologous or heterologous desensitizations of OA-NO2, AITC and capsaicin evoked currents

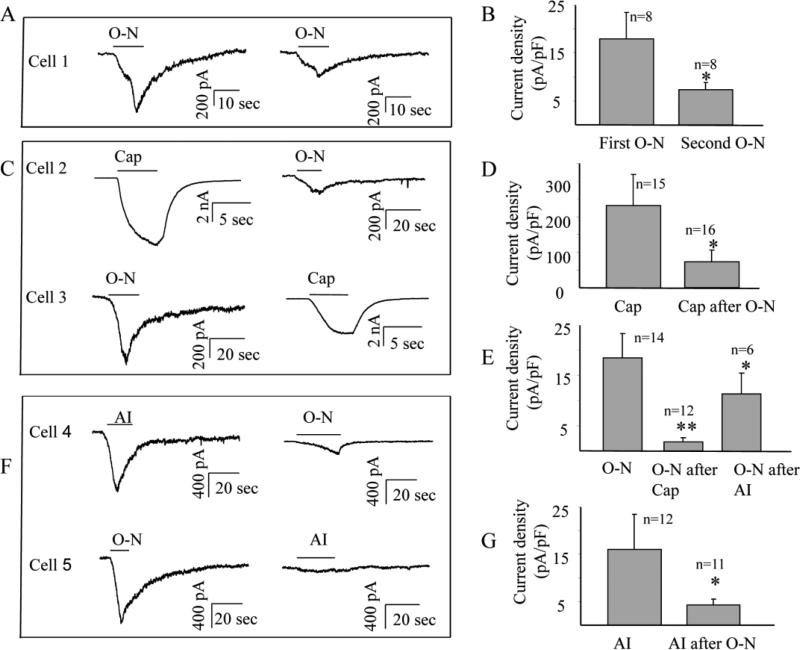

In order to test whether the homologous or heterologous desensitizations of the three agents observed in our Ca2+ imaging studies occurred at the ion channel level, OA-NO2, AITC and capsaicin evoked currents were recorded in small sized (<30 μm) DRG neurons from 4 rats. Application of OA-NO2 (30 μM) for 10 sec, AITC (100 μM) for 10 sec and capsaicin (500 nM) for 4 sec evoked inward currents in 48 % (25 of 52), 43 % (13 of 30) and 90 % (36 of 40) of DRG neurons respectively. The peak current density (pA/pF) was used to evaluate the desensitization. Since homologous and heterologous desensitization between capsaicin and AITC were extensively examined in other studies (Akopian et al., 2007; Ruparel et al., 2008), only homologous desensitization of OA-NO2 and heterologous desensitization between OA-NO2 and AITC or between OA-NO2 and capsaicin were examined in our study. To elicit homologous desensitization, OA-NO2 was applied two times at a 3-5 min interval in 8 neurons. Homologous desensitization (a 50% decrease in peak current) occurred in every neuron (p<0.05) (Figure 6A and B). To examine heterologous desensitization, the conditioning agonist was always applied 3-5 min before the test agonist and the peak current density was measured. Consistent with our Ca2+ imaging study, application of OA-NO2 significantly reduced the peak currents elicited by capsaicin or AITC (Figure 6 C, D, F and G); and prior application of capsaicin or AITC reduced the peak currents elicited by the subsequent application of OA-NO2 (Figure 6 C, E and F).

Figure 6.

Homologous or heterologous desensitization revealed by patch clamp recording of agonist evoked inward currents. OA-NO2 (O-N, 30 μM) was applied for 10 sec, capsaicin (Cap, 500 nM) was applied for 4 sec and AITC (AI, 100 μM) was applied for 10 sec. The peak current density (pA/pF) was used to evaluate the desensitization. (A) Homologous desensitization of O-N showing the second application of O-N 3 min after the first evoked a significantly smaller inward current (Cell 1). (B) pooled data from 8 neurons showing homologous desensitization of O-N (*: p<0.05). (C, D and E) Heterologous desensitization between Cap and O-N. (C) The O-N evoked current (cell 2) recorded 3 min after the application of Cap was smaller than that recorded when O-N was applied first (cell 3). The Cap evoked current was smaller when recorded 3 min after the application of O-N (cell 3) in comparison to the Cap response in cell 2 when Cap was applied first. (D) pooled data demonstrating heterologous desensitization between O-N and Cap (*: p<0.05). (E) pooled data demonstrating heterologous desensitization between Cap and O-N (**: p<0.01) and between AI and O-N (*: p<0.05). (F and G) Heterologous desensitization between AI and O-N. (F) the O-N evoked current was smaller 3 min after application of AI (cell 4) in comparison to O-N response elicited when O-N applied first (cell 5). The AI evoked current was smaller (cell 5) 3 min after application of O-N in comparison the current in another neuron (cell 4) in which AI was applied first. (G). pooled data demonstrating heterologous desensitization between O-N and AI (*: p<0.05).

Intraplantar injection of OA-NO2 induces nociceptive behavior and desensitizes AITC induced nociceptive behavior

Comparison of AITC, capsaicin and OA-NO2 induced nociceptive behaviors

In agreement with previous reports (Lu et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2009), intraplantar injections (total volume 35 μL) of AITC (10 mM, n=12 rats) or capsaicin (100 μM, n=6 rats) elicited rapid onset and short lasting nociceptive responses that consisted of licking or repeated withdrawals of the injected paw. The responses usually persisted for less than 10 min (Fig. 7A). Quantifying the magnitude of the behavior by counting the time spent licking or withdrawing the paw revealed that the peak capsaicin response was more than four-fold greater than the peak AITC response recorded during the first five minute period after injection. On the other hand, injections of OA-NO2 (2.5 mM elicited delayed onset (latency, 3 to 5 min) and more prolonged nociceptive responses in most of the rats (16 of 20 rats), an event that peaked at 5-10 min and disappeared 20-25 min after injection (Fig.7A). The peak OA-NO2 response was two-fold greater than the AITC response and approximately 50% of the capsaicin response. A lower concentration of OA-NO2 (0.25 mM) induced a weak nociceptive response (amplitude, 25% of 2.5 mM response) in 1 of 4 rats. Control injections of the same concentration of oleic acid (2.5 mM, 35 μl) did not induce nociceptive behaviors (n=3 rats). Injections of vehicles (1% DMSO for AITC; 1% ethanol for capsaicin) also did not induce nociceptive responses in 6 of 6 rats; while the OA-NO2 vehicle (10% ethanol) induced a small nociceptive response (amplitude, 10 % of the 2.5 mM response) in 2 of 6 rats, however, the responses were of shorter duration than the OA-NO2 (2.5 mM) response, disappearing in 10 min.

Figure 7.

OA-NO2 (O-N), AITC (AI) and capsaicin (Cap) induced nociceptive behavior and homologous/ heterologous desensitization of the agonist responses. The nociceptive responses were measured by counting the time spent licking or withdrawing the hindpaw during 5 min periods postinjection. (A) The nociceptive responses to AI and Cap were rapid in onset while the response to O-N was delayed and long lasting. (B) Homologous desensitization occurred with AI and Cap (p<0.05), but did not occur with O-NNO2 (p>0.05). The interval for two O-N injections was 30 min period; the interval for two AI or Cap injections was 15 min. The O-N response was measured during 30 min, AI and Cap responses were measured during the first 5 min. (C) Pretreatment with O-N induced heterologous desensitization of AI evoked responses but did not alter Cap evoked nociceptive behaviors. AI and Cap were injected 30 min after O-N.

Homologous desensitization of the nociceptive responses

Rats received two injections of the same agent at a 15 min interval for capsaicin or AITC and at a 30 min interval for OA-NO2. Homologous desensitization (Fig. 7B) was observed in all 6 rats for capsaicin, in 9 of 11 rats for AITC. However in 2 of 11 rats the response to the second AITC injection was enhanced. Homologous desensitization was not observed in 5 rats for OA-NO2 (Fig. 7B).

OA-NO2 pretreatment desensitizes AITC but not capsaicin nociceptive responses

Pretreatment with OA-NO2 (2.5 mM) 30 min before AITC at an interval when the OA-NO2 nociceptive behavior had disappeared, significantly reduced by 50% (p<0.05, Fig. 7C) the AITC evoked nociceptive responses (n=10 rats). However, a similar pretreatment with 2.5 mM OA-NO2 30 min before capsaicin did not alter capsaicin responses (n=6, Fig. 7C) (p>0.05).

Discussion

Homologous or heterologous desensitization is an important mechanism for the regulation of TRPV1 and TRPA1 channel activity and nociceptive functions. Our study revealed that the electrophilic fatty acid OA-NO2: a) desensitizes TRPV1 and TRPA1 agonist-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ as well as inward currents in dissociated DRG neurons in vitro and b) reduces nociceptive behavior elicited in vivo by intraplantar injection of AITC, a TRPA1 agonist. These results suggest that OA-NO2 might be useful clinically to reduce inflammation and certain types of painful sensations.

Previous studies on rat DRG neurons (Sculptoreanu et al., 2010) and afferent nerves in the rat urinary bladder (Artim et al., 2011) revealed that OA-NO2 activates TRPA1, TRPV1 and possibly other ion channels. Also, OA-NO2 activated TRPA1 but not TRPV1 channels in mouse trigeminal or vagal sensory neurons (Taylor-Clark et al., 2009). More recent observations suggest that OA-NO2 activates multiple Ca2+ permeable ion channels in guinea pig DRG neurons, including TRPA1, TRPV1 and unidentified channels that represent the major target in these neurons (unpublished data). Thus the neuronal effects of OA-NO2 are likely mediated by multiple mechanisms depending upon the species and the type of sensory neuron.

A comparison of Ca2+ responses to different agonists indicates that the actions of OA-NO2 more closely resemble the responses elicited by AITC. For example, the percentage of neurons responding to OA-NO2 and AITC (25-35% responsive), the long latency of the responses, the monophasic time course of the respective signals, the time for 50% decay of the signals and the overlap of responsive cells (95% exhibited coactivation) suggests that these two agonists activate a similar mechanism that is distinct from that of capsaicin. This latter agonist activated a larger percentage of cells (70%) at a shorter latency with a biphasic time course, a faster time for 50% decay and less overlap with cells responding to the other agonists. These data are consistent with the view that OA-NO2, like AITC, targets TRPA1 channels.

Notably, desensitization studies also revealed differences, as well as similarities, in the actions of OA-NO2 and AITC. The molecular mechanisms that underlie homologous or heterologous desensitization of TRP channels have been extensively studied in vivo and in vitro (Akopian et al., 2007; Ruparel et al., 2008; Salas et al., 2009). Desensitization of TRPV1 by capsaicin (homologous) or by AITC (heterologous) is mediated by dephosphorylation of the channel by phosphatase 2B (calcineurin). On the other hand, desensitization of TRPA1 by AITC (homologous) or by capsaicin (heterologous) is a calcineurin independent process. These observations were confirmed herein using deltamethrin to block phosphatase activity (Table 3). OA-NO2-induced homologous desensitization was unaffected by deltamethrin; therefore was similar to the homologous desensitization of AITC but distinct from the homologous desensitization elicited by capsaicin, that was markedly reduced by deltamethrin. The magnitude of the AITC homologous desensitization was markedly weaker than that produced by OA-NO2 (Table 2). Two applications of AITC also elicited potentiation rather than desensitization in large percentage (40%) of cells; while potentiation was less common (10% of cells) with OA-NO2 and capsaicin. Thus OA-NO2 does not mimic all of the effects of AITC.

Differences between OA-NO2 and AITC heterologous desensitization responses were also evident. Suppression of AITC or capsaicin responses by pretreatment with OA-NO2 was resistant to deltamethrin, indicating that it was phosphatase independent; while heterologous desensitization of OA-NO2 or capsaicin responses by pretreatment with AITC was reduced by deltamethrin, indicating partial phosphatase dependence. These observations do not support that OA-NO2 elicits effects on sensory neurons exclusively by activating TRPA1 channels.

It is noteworthy that OA-NO2 homologous desensitization and OA-NO2 heterologous desensitization of capsaicin or AITC responses were all phosphatase-independent processes, whereas desensitizations evoked by capsaicin or AITC were partially phosphatase dependent (Table 3). This supports that OA-NO2 activates targets other than TRPV1 and TRPA1 and/or activates multiple signaling mechanisms, such as activation of phospholipase C and depletion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), which contribute to some types of TRP channel desensitization (Akopian et al., 2007). The failure of OA-NO2 to duplicate the effects of either capsaicin or AITC could be due to simultaneous activation of multiple channels that produces a combination of homologous and heterologous desensitization of TRPV1 and TRPA1.

Homologous potentiation with two applications of capsaicin was detected in previous studies of dissociated DRG neurons (Zhang et al., 2011) and was also demonstrated by measuring contractions of bladder strips during repeated applications of low concentrations (5 μM) of OA-NO2 ; while higher concentrations of OA-NO2 elicited desensitization (Artim et al., 2011). Repeated applications of mustard oil, which stimulates TRPA1 receptors, can enhance nociceptive behaviors (Schmidt et al., 2009). However heterologous potentiation was not observed herein, possibly due to the short testing interval. Potentiation occurred with multiple applications of capsaicin when the interval between applications was long (greater than 30 minutes) or following block of desensitization with deltamethrin (Zhang et al., 2011). Potentiation is mediated by intracellular signaling pathways involving CaM kinase II and ERK1/2 (Zhang et al., 2011), signaling mediators that are also activated by fatty acid nitroalkenes (Guo et al., 2011).

The nociceptive behavior induced by intraplantar injection of OA-NO2 is consistent with the evidence that OA-NO2 can excite nociceptive afferents, but this does not establish whether the effect is due to a direct action on afferent nerves or an indirect effect due to release of endogenous substances that in turn activate the nerves. Rapid onset activation of afferent nerves by OA-NO2 has also been observed in vagal afferent pathways innervating the lung (Taylor-Clark et al., 2009). In the present study, the delayed (3-5 min) and prolonged (25-30 min) nociceptive response to OA-NO2, in contrast to the rapid onset (less than 30 sec) and transient responses to capsaicin and AITC, raises the possibility that the effect of OA-NO2 is indirect. An indirect mechanism might involve modulation of the release of inflammatory mediators from non-neuronal cells expressing TRP channels (Fernandes et al., 2012). Activation of mast cells by other agents is known to elicit a prolonged hyperalgesia (Chatterjea et al., 2012). OA-NO2 could also activate mast cells indirectly by releasing neurokinins from nociceptive afferent terminals that in turn stimulate NK-1 receptors on mast cells to release mediators (Kulka et al., 2008). OA-NO2 activation of TRPV1 and TRPA1 channels on bladder afferent nerves also induces the release of neurokinins in bladder strip preparations that in turn elicits delayed contractions of bladder smooth muscle (Artim et al., 2011). Alternatively, the delayed, indirect mechanism might be due in part to the metabolism of OA-NO2 into other active lipid compounds or release of NO, although a possible contribution of NO to the actions of OA-NO2 on dissociated neurons in vitro has been eliminated by pharmacological experiments using an NO scavenger (Sculptoreanu et al., 2010).

The intraplantar injection of OA-NO2 also suppressed the nociceptive behavior elicited by a subsequent injection of AITC but did not alter the responses to subsequent injections of capsaicin or OA-NO2. On the other hand, repeat intraplantar applications of AITC or capsaicin produced homologous desensitization of their nociceptive behaviors consistent with the desensitization observed in vitro. The absence in vivo of OA-NO2 induced homologous desensitization as well as one type of heterologous desensitization indicates that the in vitro data obtained from dissociated neurons are not directly transferable in every case to the whole animal. There are several possible explanations for the differences: (1) afferents that are not responsive to OA-NO2 may play an important role in capsaicin induced nociceptive behavior; (2) the properties of the channels on sensory nerve terminals in vivo are different than those expressed on dissociated sensory neurons or the properties of these channels are altered by the dissociation/cell culture procedures; (3) as mentioned above, effects on nerve terminals in vivo might involve indirect effects of OA-NO2 on other types of cells (eg., mast cells) that influence the nerve terminal excitability. Although the reasons for the negative findings are uncertain, it seems likely that the OA-NO2 induced suppression of AITC responses observed in vitro as well as in vivo are both mediated by the same mechanism, i.e., selective desensitization of TRPA1, rather than a general suppression of afferent nerve excitability. If OA-NO2 were acting non-selectively to suppress the excitability of the afferent nerves by blocking Na+ channels or opening K+ channels rather desensitizing TRPA1, then OA-NO2 should have suppressed capsaicin as well as AITC responses because TRPA1 and TRPV1 are co-expressed on the same sensory nerves.

The finding that pretreatment with OA-NO2 desensitizes TRPV1 and TRPA1 channels on dissociated sensory neurons in vitro and reduces the nociceptive behavior induced by intraplantar injections of AITC in vivo raises the possibility that endogenously-produced or exogenously-administered electrophilic nitro- or α,β-unsaturated oxo-fatty acids might be effective in reducing certain types of inflammation and pain by targeting TRP channels. This desensitization of TRP channels may act synergistically with other anti-inflammatory actions of nitro-fatty acids that involve pleiotropic signaling actions including: (1) inhibition of NF-κB signaling, (2) partial agonist activity towards peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) and (3) activation of Keap1/Nrf2-regulated Phase 2 gene expression (Schopfer et al., 2011). Some of these responses (PPARγ and Keap1/Nrf2) are dependent on changes in gene expression and have a slow onset; whereas others (inhibition of NF-kB signaling) also have a component of rapid onset similar to the desensitization of TRP channels. For example in a model of vascular inflammation, intravenous administration of a nitro-fatty acid reduced inflammatory responses by disrupting toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) signaling complex assembly in lipid rafts, which are upstream events in pro-inflammatory NF-κB signaling (Villacorta et al., 2013). The OA-NO2-induced phosphatase-independent homologous and heterologous desensitization responses observed in the present experiments might be related to a similar effect on lipid rafts that in turn alters the trafficking of TRP channels to and from the plasma membrane (Schmidt et al., 2009).

A potential problem in using OA-NO2 to treat pain and inflammation is that initially it could induce pain by activating TRP channels on nociceptive afferents. However this initial stimulating effect might be eliminated by starting treatment with low doses of OA-NO2. Indeed our previous studies (Sculptoreanu et al., 2010) which evaluated the effects of increasing concentrations of OA-NO2 on DRG cells revealed that after application of very low concentrations (0.005-0.05 μM) higher concentrations (5 μM) could then be administered without exciting the cells. Thus a treatment paradigm in which the drug dose is gradually increased might be the most useful approach. Clearly more clinically relevant animal studies are needed to evaluate the analgesic effects of oral dosing with the drug to determine its effects on animal behavior and also to examine its onset and duration of action as an analgesic.

In summary, calcium imaging and patch clamp recording in dissociated DRG neurons revealed that pretreatment with OA-NO2, an agent that activates TRPV1 and TRPA1 channels reduced the responses induced by a TRPV1 agonist (capsaicin) or a TRPA1 agonist (AITC). This heterologous desensitization by OA-NO2 was not affected by a phosphatase inhibitor; and therefore must be mediated by a different mechanism than the heterologous desensitization of OA-NO2 responses by either capsaicin or AITC that was reduced by phosphatase inhibition. Pretreatment with OA-NO2 also suppressed AITC induced nociceptive behavior in vivo. These results raise the possibility that OA-NO2 might be useful clinically to reduce neurogenic inflammation and certain types of painful sensations by desensitizing TRPA1 expressing nociceptive afferents.

Highlight.

Nitro-oleic acid desensitizes AITC and capsaicin induced Ca2+ increase and inward current.

Phosphatase inhibitor did not alter the nitro-oleic acid desensitization effects.

Phosphatase inhibitor reduced the capsaicin or AITC induced desensitization of OA-NO2.

Subcutaneous injection of nitro-oleic acid induced nociceptive behavior.

Subcutaneous injection of nitro-oleic acid reduced AITC-evoked nociceptive behaviors.

Acknowledgement

We thank Stephanie L Daugherty for her kind assistance editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institute of Health [Grant DK-091253].

Abbreviations

- AITC

allyl-isothiocyanate

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- OA-NO2

Nitro-oleic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- Akopian AN, Ruparel NB, Jeske NA, Hargreaves KM. Transient receptor potential TRPA1 channel desensitization in sensory neurons is agonist dependent and regulated by TRPV1-directed internalization. J Physiol. 2007;583:175–193. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artim DE, Bazely F, Daugherty SL, Sculptoreanu A, Koronowski KB, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Freeman BA, de Groat WC. Nitro-oleic acid targets transient receptor potential (TRP) channels in capsaicin sensitive afferent nerves of rat urinary bladder. Exp Neurol. 2011;232:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PR, Lin Y, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Groeger AL, Batthyany C, Sweeney S, Long MH, Iles KE, Baker LM, Branchaud BP, Chen YE, Freeman BA. Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: multiple nitrated unsaturated fatty acid derivatives exist in human blood and urine and serve as endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42464–42475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504212200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PR, Schopfer FJ, Sweeney S, Freeman BA. Red cell membrane and plasma linoleic acid nitration products: synthesis, clinical identification, and quantitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11577–11582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402587101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batthyany C, Schopfer FJ, Baker PR, Duran R, Baker LM, Huang Y, Cervenansky C, Branchaud BP, Freeman BA. Reversible post-translational modification of proteins by nitrated fatty acids in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20450–20463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602814200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonacci G, Baker PR, Salvatore SR, Shores D, Khoo NK, Koenitzer JR, Vitturi DA, Woodcock SR, Golin-Bisello F, Cole MP, Watkins S, St Croix C, Batthyany CI, Freeman BA, Schopfer FJ. Conjugated linoleic acid is a preferential substrate for fatty acid nitration. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:44071–44082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjea D, Wetzel A, Mack M, Engblom C, Allen J, Mora-Solano C, Paredes L, Balsells E, Martinov T. Mast cell degranulation mediates compound 48/80-induced hyperalgesia in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;425:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles B, Bloodsworth A, Clark SR, Lewis MJ, Cross AR, Freeman BA, O'Donnell VB. Nitrolinoleate inhibits superoxide generation, degranulation, and integrin expression by human neutrophils: novel antiinflammatory properties of nitric oxide-derived reactive species in vascular cells. Circ Res. 2002a;91:375–381. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000032114.68919.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles B, Bloodsworth A, Eiserich JP, Coffey MJ, McLoughlin RM, Giddings JC, Lewis MJ, Haslam RJ, Freeman BA, O'Donnell VB. Nitrolinoleate inhibits platelet activation by attenuating calcium mobilization and inducing phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein through elevation of cAMP. J Biol Chem. 2002b;277:5832–5840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui T, Schopfer FJ, Zhang J, Chen K, Ichikawa T, Baker PR, Batthyany C, Chacko BK, Feng X, Patel RP, Agarwal A, Freeman BA, Chen YE. Nitrated fatty acids: Endogenous anti-inflammatory signaling mediators. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35686–35698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603357200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa DS, Meotti FC, Andrade EL, Leal PC, Motta EM, Calixto JB. The involvement of the transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1) in the maintenance of mechanical and cold hyperalgesia in persistent inflammation. Pain. 2010;148:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Wang S, Tominaga M, Yamamoto S, Fukuoka T, Higashi T, Kobayashi K, Obata K, Yamanaka H, Noguchi K. Sensitization of TRPA1 by PAR2 contributes to the sensation of inflammatory pain. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1979–1987. doi: 10.1172/JCI30951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JB, Gray J, Gunthorpe MJ, Hatcher JP, Davey PT, Overend P, Harries MH, Latcham J, Clapham C, Atkinson K, Hughes SA, Rance K, Grau E, Harper AJ, Pugh PL, Rogers DC, Bingham S, Randall A, Sheardown SA. Vanilloid receptor-1 is essential for inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia. Nature. 2000;405:183–187. doi: 10.1038/35012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes ES, Fernandes MA, Keeble JE. The functions of TRPA1 and TRPV1: moving away from sensory nerves. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:510–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01851.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo CJ, Schopfer FJ, Gonzales L, Wang P, Freeman BA, Gow AJ. Atypical PKC€ transduces electrophilic fatty acid signaling in pulmonary epithelial cells. Nitric Oxide. 2011;25:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Fukuoka T, Obata K, Yamanaka H, Dai Y, Tokunaga A, Noguchi K. Distinct expression of TRPM8, TRPA1, and TRPV1 mRNAs in rat primary afferent neurons with Aδ/c-fibers and colocalization with trk receptors. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:596–606. doi: 10.1002/cne.20794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka M, Sheen CH, Tancowny BP, Grammer LC, Schleimer RP. Neuropeptides activate human mast cell degranulation and chemokine production. Immunology. 2008;123:398–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02705.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YC, Chen CW, Wang SY, Wu FS. 17Beta-estradiol mediates the sex difference in capsaicin-induced nociception in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:1104–1110. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.158402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson LJ, Dubin AE, Evans MJ, Marr F, Schultz PG, Cravatt BF, Patapoutian A. Noxious compounds activate TRPA1 ion channels through covalent modification of cysteines. Nature. 2007;445:541–545. doi: 10.1038/nature05544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruparel NB, Patwardhan AM, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. Homologous and heterologous desensitization of capsaicin and mustard oil responses utilize different cellular pathways in nociceptors. Pain. 2008;135:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas MM, Hargreaves KM, Akopian AN. TRPA1-mediated responses in trigeminal sensory neurons: interaction between TRPA1 and TRPV1. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:1568–1578. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Dubin AE, Petrus MJ, Earley TJ, Patapoutian A. Nociceptive signals induce trafficking of TRPA1 to the plasma membrane. Neuron. 2009;64:498–509. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer FJ, Cipollina C, Freeman BA. Formation and signaling actions of electrophilic lipids. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5997–6021. doi: 10.1021/cr200131e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sculptoreanu A, Kullmann FA, Artim DE, Bazley FA, Schopfer F, Woodcock S, Freeman BA, de Groat WC. Nitro-oleic acid inhibits firing and activates TRPV1- and TRPA1-mediated inward currents in dorsal root ganglion neurons from adult male rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333:883–895. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.163154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Clark TE, Ghatta S, Bettner W, Undem BJ. Nitrooleic acid, an endogenous product of nitrative stress, activates nociceptive sensory nerves via the direct activation of TRPA1. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:820–829. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.054445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villacorta L, Chang L, Salvatore SR, Ichikawa T, Zhang J, Petrovic-Djergovic D, Jia L, Carlsen H, Schopfer FJ, Freeman BA, Chen YE. Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids inhibit vascular inflammation by disrupting LPS-dependent TLR4 signalling in lipid rafts. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;98:116–124. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villacorta L, Zhang J, Garcia-Barrio MT, Chen XL, Freeman BA, Chen YE, Cui T. Nitro-linoleic acid inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H770–776. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00261.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MM, Schopfer FJ, Baker PR, Vidyasagar V, Powell P, Chumley P, Iles KE, Freeman BA, Agarwal A. Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: nitrolinoleic acid potently activates endothelial heme oxygenase 1 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4299–4304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506541103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Daugherty SL, de Groat WC. Activation of CaMKII and ERK1/2 contributes to the time-dependent potentiation of Ca2+ response elicited by repeated application of capsaicin in rat DRG neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R644–654. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00672.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]