Abstract

Utilizing a combination of high-throughput and multi-step synthesis, SAR in a novel series of M1 acetylcholine receptor antagonists was rapidly established. The efforts led to the discovery the highly potent M1 antagonists 6 (VU0431263), and 8f (VU0433670). Functional Schild analysis and radioligand displacement experiments demonstrated the competitive, orthosteric binding of these compounds; human selectivity data are presented.

Keywords: Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor 1, M1 antagonist, VU0433670, VU0431263, Fluorination

Acetylcholine mediates the metabotropic actions of the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) which are in turn part of the class A, or rhodopsin-like G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family.1-4 To date, five subtypes of mAChR have been identified, termed M1–M55. The mAChRs are widely distributed throughout both the periphery and the central nervous system (CNS), and muscarinic receptor signaling is implicated in a large number of physiological functions including memory and attention, motor control, nociception, regulation of sleep-wake cycles, cardiovascular function, and renal and gastrointestinal function. For this reason, a large amount of effort has been devoted to the development of subtype-selective muscarinic modulators to treat various diseases. Antagonism of the M1 subtype has the potential to play a role in the treatment of several CNS pathologies, including Parkinson’s disease and Fragile × syndrome.6,7 As such, and as part of our continued interest10-13 in understanding the broader implications of muscarinic receptor modulation, we sought to identify a potent M1 antagonist with an acceptable selectivity profile against the other four mAChRs (M2–M5).

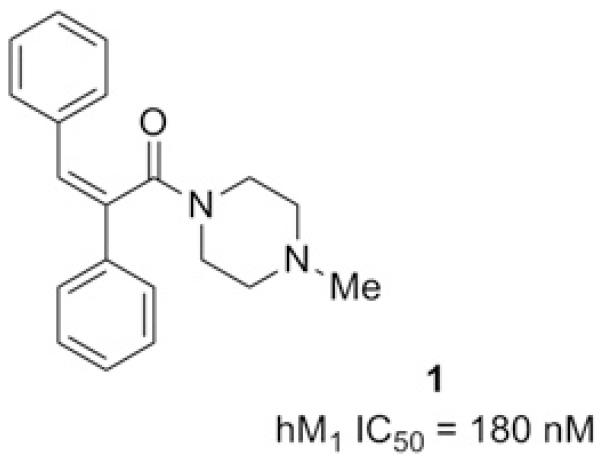

After conducting a high-throughput screen of the Vanderbilt compound collection, 1 was identified (Fig. 1) and deemed to be a potentially attractive starting point owing to its good potency (hM1 IC50 = 180 nM) and acceptably low molecular weight (306 Da), despite the presence of an obvious Michael acceptor, and the concomitant risk16 of covalent protein modification. Additionally, the amenability of amide coupling to parallel synthesis represented an opportunity to rapidly develop a structure-activity relationship (SAR) around the piperazine portion of the molecule. We chose a kinetic functional assay and employed a triple-add protocol14,15 as part of our routine screening paradigm, on the basis of its high throughput and its ability to detect alternative modes of pharmacology (i.e., agonism, positive and negative allosteric modulation).

Figure 1.

HTS hit selected for follow-up.

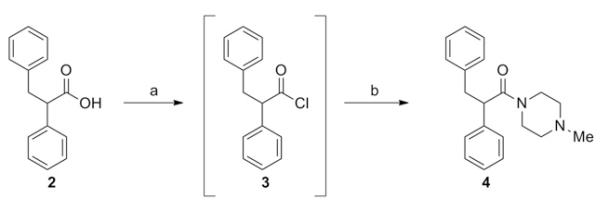

We initially turned our attention to removing the α,β-unsaturated amide moiety, as this functionality could be associated with undesirable covalent protein modification. Starting from commercially available 2,3-diphenylpropionic acid (2), the corresponding acid chloride was generated in situ using 1-Chloro-N,N,2-trimethyl-1-propenylamine8 (Ghosez’s reagent). Exposure of acid chloride 3 to 4-methylpiperazine afforded 4, the reduced analog of 1 (Scheme 1). We were encouraged to find that saturation of the central double bond of 1 resulted in a roughly fourfold improvement in antagonist potency, prompting us to more thoroughly explore the SAR of this class of compound.

Scheme 1.

Reagents: (a) 1-Chloro-N,N,2-trimethyl-1-propenylamine (Ghosez’s reagent), DCM, RT, 10 min. (b) amine, DIEA, DCM, RT, 1 h (80%).

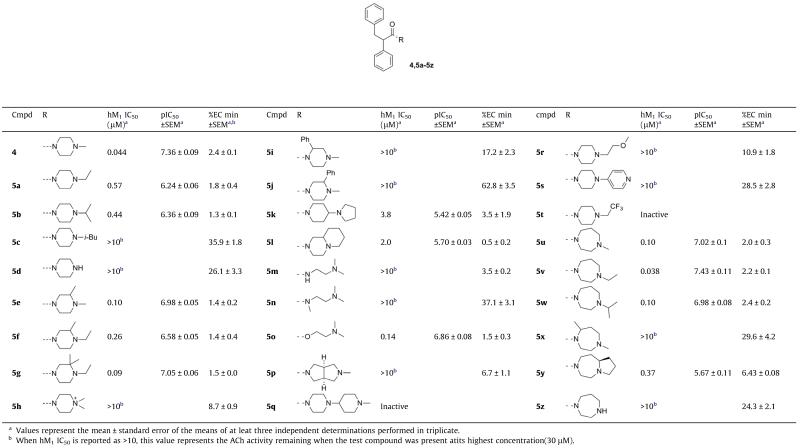

As shown in Table 1, slightly increasing the size of the terminal nitrogen substituent from methyl to ethyl (5a) caused a sixfold drop in potency. Continuing to increase the size of this substituent to isopropyl (5b) resulted in only a minor potency decrease, but installation of an isobutyl group (5c) nearly abolished antagonist activity. Branching groups adjacent to the terminal nitrogen were somewhat better tolerated, and methyl and gem-dimethyl substitution adjacent to an ethyl capped piperazine (5f and 5g) actually served to increase potency roughly sixfold relative to the unsubstituted compounds. Removal of the terminal substituent to generate a secondary amine (5d) caused a loss of activity. Attempts to open the piperazine ring by attaching acyclic amines resulted in large losses in potency (5m and 5n), the exception being the ester 5o, which may somewhat mimic the endogenous agonist acetylcholine. The terminal piperazine nitrogen of 4 was also quaternized, as an additional attempt to approximate acetylcholine, but the resulting compound 5h displayed only modest activity. We speculated that these attempts to mimic acetylcholine, while academically tempting, would ultimately result in diminished subtype selectivity, and were not pursued further.

Table 1.

Structures and activities of analogs 4,5a-z with different amide groups (R)

|

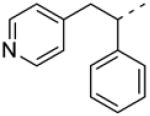

Attempts to modulate the basicity of the terminal nitrogen were met with limited success; attachment of a trifluoroethyl group rendered the terminal nitrogen non-basic, and resulted in a complete loss of activity (5t). Installation of a 4-pyridyl group, while lowering the basicity to a lesser degree, nevertheless resulted in a compound with minimal antagonist activity (5s). Even the relatively modest pKa lowering effect afforded by the presence of a β-ether caused a significant drop in potency (5r), suggesting that a steric effect could also be causing these reductions in potency (similar to the 4, 5a and 5c analog progression).

A number of homopiperazines were also prepared, and SAR was found to be slightly more’forgiving’ relative to the piperazine series. Thus, methyl homopiperazine 5u displayed only a twofold decrease in potency relative to our lead compound 4, and ethyl homopiperazine 5v was roughly equipotent with 4, in contrast to the 4 to 5a comparison. N-Isopropyl homopiperazine 5w and the bicyclic compound 5y both retained moderate potency, but removal of the terminal homopiperazine substituent resulted in a nearly complete loss of activity (5z), analogously to 5d.

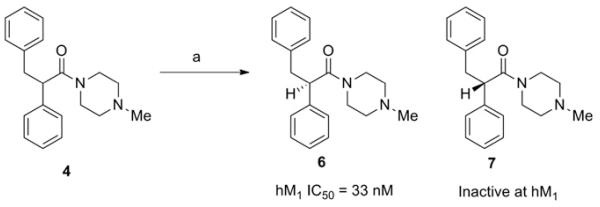

Concurrent with our efforts to improve potency by varying the eastern amide substituent, we pursued the separation of our racemic lead compound 4 into individual enantiomers (Scheme 2). Gratifyingly, it was discovered that all the activity of 4 was derived from a single stereoisomer of yet-to-be determined absolute chirality. The more rapidly eluting enantiomer, 6 represented a moderate improvement in potency in the series, and it was envisioned that this striking stereospecificity could also increase subtype selectivity.

Scheme 2.

Conditions: (a) CHIRALPAK IC, 5% MeOH (0.1% diethylamine) in CO2.

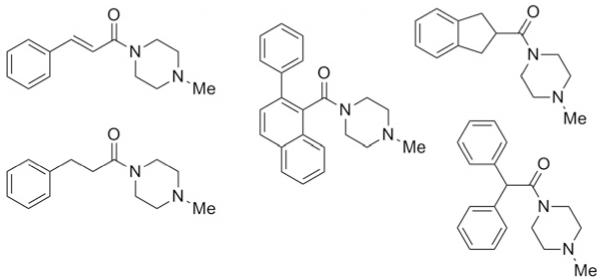

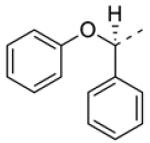

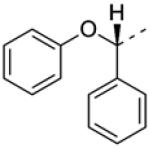

In addition to developing SAR around the eastern amide substituent, a number of modifications to the diphenyl scaffold were examined. Most of these attempts at ‘scaffold hopping’ were unsuccessful (Fig. 2), but the notable exceptions are shown in Table 2. Incorporation of heteroatoms into the lipophilic western domain was seen as a potential way to improve physical and pharmacokinetic properties, as well as selectivity against other muscarinic receptor subtypes. Replacement of the central methylene group with an oxygen was tolerated, and chiral separation demonstrated stereospecificity of the pharmacophore (8a and 8b). The distal phenyl ring could also be replaced with a pyridine (8c and 8d), with an approximately twofold preference for the 3-substitued pyridine. Although we were encouraged to see that these modifications could be carried out while maintaining sub-micromolar potency, predicted human and rat hepatic clearance values based on in vitro hepatic microsome intrinsic clearance data remained as high as those for the parent compounds, and generally approximated hepatic blood flow in each species (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Scaffold modifications that did not maintain potency (hM1 IC50 >10 μM).

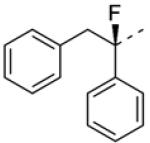

Table 2.

Structures and activities of analogs 8a–8f with alternative diaryl groups (R)

| Cmpd | R | hM1 IC50 (μM)a | %EC min ± SEMa | pIC50 ±SEMa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8a b |

|

0.24 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 6.61 ± 0.06 |

| 8b b |

|

>10 | 107 ± 1.1 | |

| 8c |

|

0.88 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 6.06 ± 0.07 |

| 8d |

|

0.50 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 6.30 ± 0.08 |

| 8e b |

|

2.4 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 5.62 ± 0.06 |

| 8f b |

|

0.018 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 7.75 ± 0.06 |

Values represent the mean ± standard error of the means of at leat three independent determinations performed in triplicate.

Absolute stereochemistry is unknown, but each resolved enantiomer displayed an ee of>95% as determined by analytical chiral HPLC.

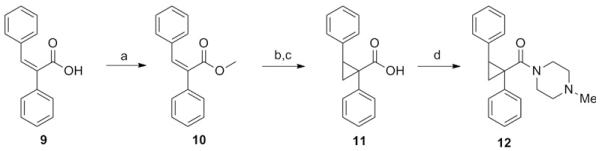

We next set about designing a compound that would maintain the potency of 6, but with diminished capacity for epimerization, since racemization could have negative implications not only for potency, but for subtype selectivity and broader off-target effects as well. Blocking the relatively acidic α-proton with a small substituent represented the most obvious approach, and the presence of an otherwise undesirable Michael acceptor in our HTS hit 1 offered, in this instance, an expedient means to the introduction of a cyclopropyl group (Scheme 3). Unfortunately, compound 12 displayed only weak antagonist activity (hM1 IC50 = 2.5 μM).

Scheme 3.

Reagents: (a) Iodomethane, DBU, toluene, reflux, 8 h (60%) (b) Trimethylsulfoxonium iodide, sodium hydride, DMSO, RT, 2 h (c) KOH, MeOH/H2O, RT, 3 h (43% for 2 steps) (d) Ghosez’ reagent, 4-methylpiperazine, DIEA, DCM, 1 h (67%).

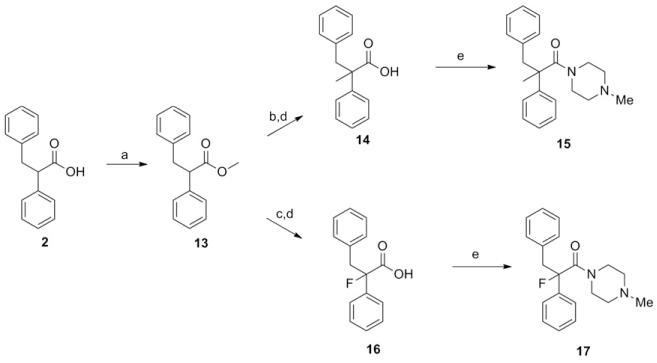

To explore the effect of α-methylation, commercially available 2 was first esterified as depicted in Scheme 4. Deprotonation with lithium diisopropylamide and trapping with iodomethane, followed by saponification and peptide coupling gave compound 15 (hM1 IC50 > 10 μM, ECmin 39.1 ± 3.6). Again, activity was sharply diminished relative to 4. Next, alpha-fluorination of the carboxamide was carried out, utilizing chemistry outlined in Scheme 4. Compound 17 exhibited a modest improvement (hM1 IC50 = 29 nM, ECmin 3.1 ± 0.3, pEC50, 7.55 ± 0.06) in potency relative to 4, and the beneficial effect of fluorination can perhaps be attributed to the known preference of alpha-fluoroamides to adopt an anti-periplanar conformation9, as well as its small size, minimizing the possibility of a steric repulsion between this α-substituent and the receptor. Chiral resolution of 17 afforded the most potent compound in the series to date, 8f (hM1 IC50 = 18 nM; Although the other enantiomer 8e appears to display measurable antagonist activity, this activity could result from the presence of less than 1% of 8f given its tremendous potency of 18 nM).

Scheme 4.

Reagents: (a) Iodomethane, DBU, toluene, reflux, 8 h (b) LDA, THF, −78°C, 30 min, then iodomethane, THF, −78 °C to ambient temperature (c) LDA, THF, −78 °C, 30 min, then NFSI, THF, −78 °C to ambient temperature (29% over 2 steps) (d) KOH, MeOH/H2O (2:1), RT (Quant.) (e) Ghosez’ reagent, DCM, RT, then 4-methylpiperazine, DIEA, DCM, RT (85% and 71% for 15 and 17, respectively).

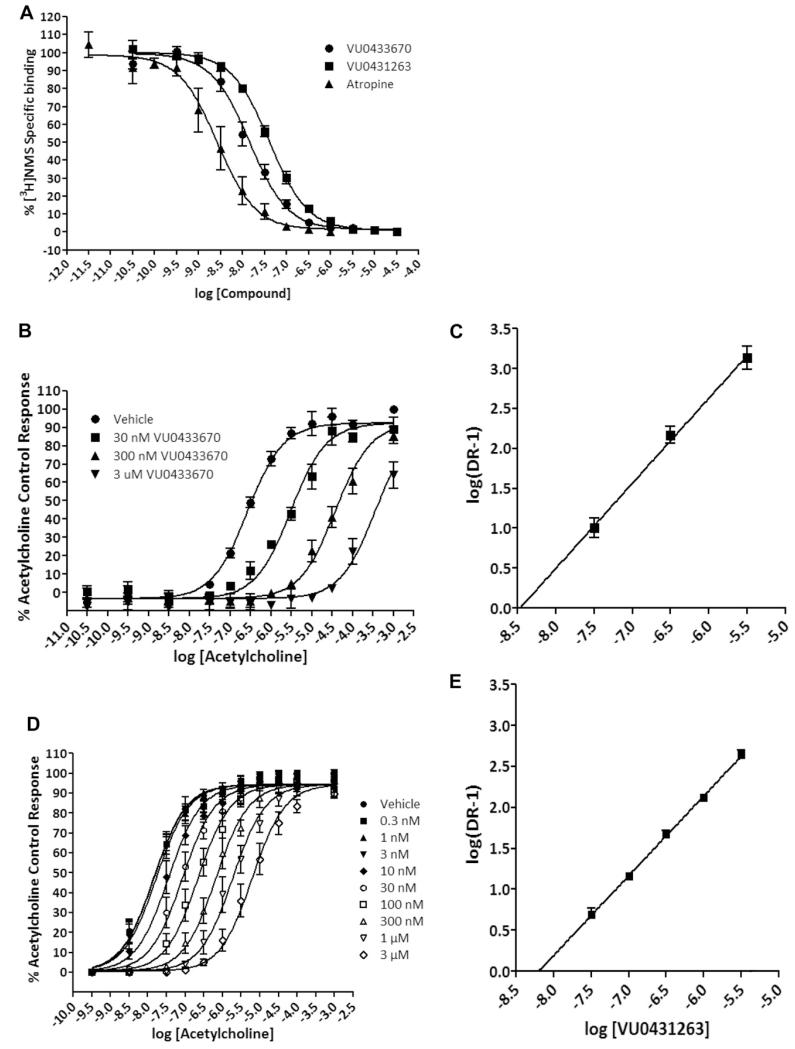

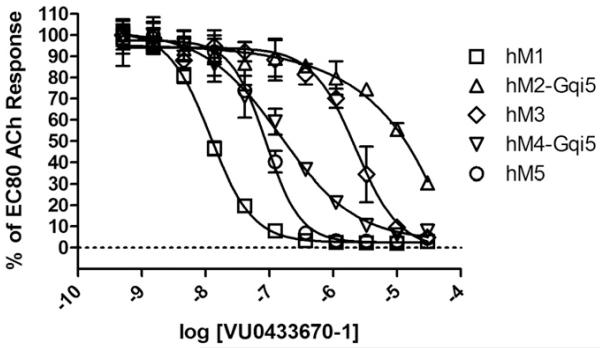

Having in hand several highly potent hM1 antagonists, we next sought to more fully understand their mode of interaction with the hM1 receptor. N-methylscopolomine (NMS) and atropine are pan-mAChR antagonists, and are known to bind in an orthosteric manner. Atropine, 8f and 6 were found to completely displace radiolabeled NMS under equilibrium conditions, a hallmark of competitive, orthosteric binding (Fig. 3A). Utilizing calcium mobilization as a functional readout in M1-expressing CHO cells, Schild analyses further supported the competitive nature of 8f and 6, as evidenced by concentration-dependant rightward shifts of ACh concentration-response curves (CRCs), and Schild slopes of unity, shown in Figure 3B-E. Despite the realization that this series of antagonists binds to the orthosteric site, the most potent compound in the series, 8f was chosen for a full selectivity screen against hM1-5, the results of which are shown in Figure 4. Although 8f displays relatively potent antagonism of hM5 and hM4 (hM5 IC50 = 82 nM; hM4 IC50 = 140 nM), an interesting degree of subtype selectivity was observed against hM2-3 (hM2-3 IC50s > 1.5 μM). The orthosteric binding sites of all five mAChRs are highly conserved, a fact which has typically frustrated efforts to selectively activate or antagonize specific subtypes using ACh-competitive ligands. However, previous work10 from our laboratories has demonstrated that through the strategic use of structural modifications, high subtype selectivity for the M1 receptor can be achieved, even in the case of competitive, orthosteric ligands.

Figure 3.

A, Compound 6 (VU0431263), 8f (VU0433670), and atropine compete with [3H]NMS binding at hM1. B, Compound 8f (VU0433670) competitively antagonizes M1 response to ACh in a concentration-dependent manner in a calcium mobilization assay. C, Schild regression of the concentration ratios derived from 8f (VU0433670) antagonism of ACh (slope of this regression is 1.07 ± 0.02. R2 = 0.992). D, Compound 6 (VU0431263) competitively antagonizes M1 response to ACh in a concentration-dependent manner in a calcium mobilization assay. E, Schild regression of the concentration ratios derived from 6 (VU0431263) antagonism of ACh (slope of this regression is 0.97 ± 0.02. R2 = 0.997). Values represent the mean ± S.E.M. of three experiments conducted in triplicate.

Figure 4.

Compound 8f displays modest selectivity for hM1 in a calcium mobilization assay.

In summary, we initiated a hit-to-lead campaign on the basis of HTS hit 1. The undesirable Michael acceptor present in 1 was quickly removed, resulting in a significant gain in potency. A large amount of SAR was quickly amassed by employing parallel synthesis. Next, traditional single-compound synthesis was employed to demonstrate that fluorination of the amide α-carbon improved potency to arrive at a compound which was 10-fold more potent than the HTS hit. Future work in this series will focus on structural modifications aimed at higher muscarinic subtype selectivity, as well as improved DMPK properties.

References and notes

- 1.Bonner TI, Buckley NJ, Young AC, Brann MR. Science. 1987;237:527. doi: 10.1126/science.3037705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonner TI, Young AC, Brann MR, Buckley NJ. Neuron. 1988;1:403. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wess J. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2004;44:423–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langmead CJ, Watson J, Reavill C. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;117:232. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wess J. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol. 1996;10:69. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v10.i1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wess J, Eglen RM, Gautam D. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:721. doi: 10.1038/nrd2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridges TM, LeBois EP, Hopkins CR, Wood MR, Jones JK, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Drug News Perspect. 2010;23:229. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2010.23.4.1416977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devos A, Remion J, Frisque-Hesbain AM, Colens A, Ghosez L. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Comm. 1979;24:1180. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkler M, Moraux T, Khairy HA, Scott RH, Slawin AMZ, O’Hagan D. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:823. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melancon BJ, Utley TJ, Sevel C, Mattmann ME, Cheung Y-Y, Bridges TM, Morrison RD, Sheffler DJ, Niswender CM, Daniels JS, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Wood MR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:5035. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melancon BJ, Lamers AP, Bridges TM, Sulikowski GA, Utley TA, Sheffler DJ, Noetzel MJ, Morrison RD, Daniels JS, Niswender CM, Jones CK, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Wood MR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;22:1044. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.11.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis LM, Sheffler DJ, Williams R, Bridges TM, Kennedy JP, Brogan JT, Mulder MJ, Williams L, Nalywajko NT, Niswender CM, Weaver CD, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:885. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheffler DJ, Williams R, Bridges TM, Xiang Z, Kane AS, Byun NE, Jadhav S, Mock MM, Zheng F, Lewis LM, Jones CK, Niswender CM, Weaver CD, Lindsley CW, Conn P. J. Mol. Pharm. 2009;76:356. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.056531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez AL, Grier MD, Jones CK, Herman EJ, Kane AS, Smith RL, Williams R, Zhou Y, Marlo JE, Days EL, Blatt TN, Jadhav S, Menon UN, Vinson PN, Rook JM, Stauffer SR, Niswender CM, Lindsley CW, Weaver CD, Conn P. J. Mol. Pharm. 2010;78:1105. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.067207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niswender CM, Johnson KA, Weaver CD, Jones CK, Xiang Z, Luo Q, Rodriguez AL, Marlo JE, de Paulis T, Thompson AD, Days EL, Nalywajko T, Austin CA, Williams MB, Ayala JE, Williams R, Lindsley CW, Conn P. J. Mol. Pharm. 2008;74:1345. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takakusa H, Masumoto H, Yukinaga H, Makino C, Nakayama S, Okazaki O, Sudo K. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008;36:1770. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.021725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]