Abstract

Purpose

To compare American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), International Union Against Cancer (UICC), and Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) tumor (T) staging systems for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and validate BWH staging against prior data.

Patients and Methods

Primary tumors diagnosed from 2000 to 2009 at BWH (n = 1,818) were analyzed. Poor outcomes (local recurrence [LR], nodal metastasis [NM], and disease-specific death [DSD]) were analyzed by T stage with regard to each staging system's distinctiveness (outcome differences between stages), homogeneity (outcome similarity within stages), and monotonicity (outcome worsening with increasing stage).

Results

AJCC and UICC T3 and T4 were indistinct with overlapping 95% CIs for 10-year cumulative incidences of poor outcomes, but all four BWH stages were distinct. AJCC and UICC high-stage tumors (T3/T4) were rare at 0.3% and 3% of the cohort, respectively. Most poor outcomes occurred in low stages (T1/T2; AJCC: 86% [95% CI, 77% to 91%]; UICC: 70% [61% to 79%]) resulting in heterogeneous outcomes in T1/T2. Conversely, in BWH staging, only 5% of tumors were high stage (T2b/T3), but they accounted for 60% (95% CI, 50% to 69%) of poor outcomes (70% of NMs and 83% of DSDs) indicating superior homogeneity and monotonicity as previously defined. Cumulative incidences of poor outcomes were low for BWH low-stage (T1/T2a) tumors (LR, 1.4% [95% CI, 1% to 2%]; NM, 0.6% [95% CI, 0% to 1%]; DSD, 0.2% [95% CI, 0% to 0.5%]) and higher for high-stage (T2b/T3) tumors (LR, 24% [95% CI, 16% to 34%]; NM, 24% [95% CI, 16% to 34%]; and DSD, 16% [95% CI, 10% to 25%], which validated an earlier study of an alternative staging system.

Conclusion

BWH staging offers improved distinctiveness, homogeneity, and monotonicity over AJCC and UICC staging. Population-based validation is needed. BWH T2b/T3 tumors define a high-risk group requiring further study for optimal management.

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 3,500,000 cases of nonmelanoma skin cancer are diagnosed annually in the United States with 700,000 being cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC), assuming a 20% proportion of CSCC.1 Most patients with CSCC have an excellent prognosis after surgical clearance.2,3 However, there is a subset of CSCC that carries increased risk of local recurrence (LR), nodal metastasis (NM), and disease-specific death (DSD).

CSCC is excluded from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) tracking because of its commonness and excellent overall prognosis. Population-based incidence of poor outcomes is therefore not available. However, risks of NM and DSD are estimated to be 3.7% to 5.2% and 1.5% to 2.1%, respectively.4–7 An estimated 3,932 to 8,791 deaths occur annually in the United States as a result of CSCC. In central and southern states, incidence of death as a result of CSCC is estimated to rival that of melanoma and several other common cancers.8

Several clinical and histologic risk factors are associated with increased risk of recurrence, metastasis, and death, including perineural or lymphovascular invasion, poorly differentiated histology, diameter of 2 cm or greater, depth beyond the dermis, location on ear or lip, recurrent tumors, and immunocompromised host status.4,6,9–11 However, high-risk CSCC has not been consistently defined, nor has associated prognosis been estimated. Clinicians have little evidence to guide decisions regarding nodal staging and adjuvant therapy. Subsequently, management varies widely.2,12,13

Recent data show high cure rates for CSCC of the head and neck when NMs are detected early and treated appropriately.14,15 Thus, accurate prediction of patients with CSCC who are at risk for metastasis may be beneficial. It may aid in the design of clinical trials and allow clinicians to target nodal staging, including sentinel node biopsy, and adjuvant therapies such as radiation or immune modulation earlier in the course of disease when they are most effective.

In 2002, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) defined the goal of cancer staging to be separation of patients into groups which are distinctive (outcomes differ between staging groups), homogeneous (outcomes are similar within staging groups), and monotonous (outcomes worsen with increasing stage).16 The AJCC and International Union Against Cancer (UICC) published revised tumor (T) staging systems for CSCC in 2010 based on expert consensus.17–19 Our group recently published the first validation study of the new AJCC T staging system by using patient outcome data.20 The study showed that the bulk of poor outcomes (83% of NMs and 92% of DSDs) occurred in AJCC T2 tumors. An alternative T staging system was developed that subdivided T2 tumors into low-risk T2a and high-risk T2b categories, the latter of which contained few patients (19% of the cohort) but the majority of poor outcomes (72% of NMs and 83% of DSDs).20 Thus, this study indicated that the alternative staging system may offer improved homogeneity and monotonicity over AJCC staging.

This study was undertaken to compare AJCC, UICC, and Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) T staging systems with regard to distinctiveness, homogeneity, and monotonicity and to validate the BWH staging system (a modification of our previously published alternative system) in a larger cohort of patients with CSCC via comparison with the initial study.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Selection

The Brigham and Women's Department of Pathology electronic database was searched for pathology reports with a diagnosis of CSCC dated January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2009. Cases of noncutaneous SCC, in situ CSCC, and recurrent (nonprimary) CSCC were excluded. Anogenital and eyelid CSCCs were also excluded because these are staged separately in AJCC and UICC T staging. Details of data collection methods are described in the Data Supplement.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis including Fine and Gray competing risk modeling21,22 was performed by using primary tumor data for each patient with CSCC. Details of the modeling methods are described in the Data Supplement.

Validation of the BWH T Staging System

To validate the newly developed BWH staging system, the results of multivariable modeling of risk factors predictive of each end point of interest were compared with the initial study of the alternative staging system to confirm that the same risk factors were again predictive. In addition, 10-year cumulative incidences of end points by T stage were compared between the initial study and this study to determine whether the same trends of increasing incidence of poor outcomes with increasing T stage were demonstrable.20

Comparison of AJCC, UICC, and BWH Staging Systems

Tumors were classified according to 2010 AJCC, 2010 UICC, and BWH T staging systems (Table 1). Life-tables of LR, NM, and DSD outcomes by T stage of each staging system were compiled. To evaluate distinctiveness of tumor staging systems, 10-year cumulative incidences with 95% CIs and pair-wise comparison tests were calculated for each end point (Gray's test for cumulative incidence function curves and log-rank test for Kaplan-Meier curves). To evaluate homogeneity, the proportion of poor outcomes (LR, NM, and DSD) occurring in low T stages was compared between staging systems. Monotonicity was evaluated by comparing the proportion of LRs, NMs, and DSDs occurring in high T stages between systems. Homogeneity and monotonicity of the staging systems were also evaluated by calculating McNemar's test for each end point.

Table 1.

Summary of the AJCC, UICC, and BWH Tumor (T) Staging Systems

| Tumor Staging System | Definition |

|---|---|

| AJCC | |

| T1 | Tumor ≤ 2 cm in greatest dimension with fewer than two high-risk factors* |

| T2 | Tumor > 2 cm in greatest dimension or with two or more high-risk factors* |

| T3 | Tumor with invasion of orbit, maxilla, mandible, or temporal bones |

| T4 | Tumor with invasion of other bones or direct perineural invasion of skull base |

| UICC | |

| T1 | Tumor ≤ 2 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| T2 | Tumor > 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| T3 | Tumor with invasion of deep structures (eg, muscle, cartilage, bone [excluding axial skeleton], orbit) |

| T4 | Tumor with invasion of axial skeleton or direct perineural invasion of skull base |

| BWH | |

| T1 | 0 high-risk factors† |

| T2a | 1 high-risk factor |

| T2b | 2-3 high-risk factors |

| T3 | ≥ 4 high-risk factors or bone invasion |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BWH, Brigham and Women's Hospital; T, tumor stage from TNM staging system; UICC, International Union Against Cancer.

AJCC high-risk factors include > 2 mm thickness, Clark level ≥ IV, perineural invasion, primary site ear, primary site non–hair-bearing lip, or poorly differentiated histology.

BWH high-risk factors include tumor diameter ≥ 2 cm, poorly differentiated histology, perineural invasion ≥ 0.1 mm, or tumor invasion beyond fat (excluding bone invasion which automatically upgrades tumor to BWH stage T3).

Cumulative incidence function curves were used to illustrate the survival probabilities of BWH T stages for competing risk end points (LR, NM, DSD), and Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used for the Cox end point of overall death (OD). All statistical analyses were performed in STATA v12.0 (STATA, College Station, TX) and R (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria http://www.R-project.org) by using a two-sided 5% type I error rate. The study was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee.

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

The pathology database yielded 1,980 primary invasive (not in situ) CSCC tumors. After medical record review, 148 tumors were excluded because of insufficient primary tumor information, and nine anogenital and five eyelid tumors were excluded, leaving 1,818 tumors in 974 patients in the final study cohort.

Baseline cohort characteristics are summarized in Table 2 along with the fraction of LR, NM, DSD, and OD occurring in each subgroup. The median age at diagnosis was 71 years (range, 37 to 93 years). The majority of patients (98%) were non-Hispanic white and male (53%). Median follow-up time was 50 months (range, 2 to 142 months). The majority of patients (n = 711 [73%]) had a single tumor, 209 (21%) had two to four tumors, and 54 (6%) had five or more tumors. One hundred forty-one patients (14%) were immunosuppressed. The majority of CSCC tumors were less than 2 cm in diameter (85%), well differentiated (66%), and did not invade subcutaneous fat or deeper structures (90%). Seventy-four tumors (4%) had perineural invasion.

Table 2.

Cohort Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. | % | LR (%) | NM (%) | DSD (%) | OD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. of patients | 974 | 42 | 33 | 18 | 281 | |

| Age, years | ||||||

| Median | 71 | |||||

| Range | 37-93 | |||||

| Follow-up time, months | ||||||

| Median | 44 | |||||

| Range | 2-130 | |||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 514 | 53 | 72 | 79 | 89 | 64 |

| Female | 460 | 47 | 28 | 21 | 11 | 36 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 954 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97 |

| African American | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No. of CSCC tumors | ||||||

| 1 | 711 | 73 | 46 | 42 | 72 | 66 |

| 2-4 | 209 | 21 | 28 | 36 | 28 | 25 |

| 5-9 | 35 | 4 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| ≥ 10 | 19 | 2 | 15 | 16 | 0 | 3 |

| Immunosuppression | ||||||

| No | 833 | 86 | 83 | 79 | 94 | 78 |

| Yes | 141 | 14 | 17 | 21 | 6 | 22 |

| Reason for immunosuppression | 141 | |||||

| Organ transplantation | 57 | 41 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 9 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis immunosuppressive therapy | 36 | 25 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 23 | 16 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 5 |

| Other immunosuppressive therapy or disease | 25 | 18 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

| Tumor characteristics | ||||||

| Total CSCC tumors | 1,818 | 47 | 33 | 18 | 609 | |

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Head/neck (excluding ear and temple) | 521 | 28 | 55 | 54 | 50 | 31 |

| Ear/temple | 159 | 9 | 17 | 18 | 22 | 11 |

| Arms/hand | 395 | 22 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 21 |

| Trunk | 308 | 17 | 13 | 22 | 28 | 19 |

| Legs/feet | 435 | 24 | 13 | 3 | 0 | 18 |

| Tumor diameter, cm | ||||||

| Median | 1.1 | |||||

| Range | 0.2-12.5 | |||||

| < 2 | 1,550 | 85 | 45 | 30 | 22 | 85 |

| ≥ 2 | 233 | 13 | 51 | 52 | 67 | 12 |

| Unknown | 35 | 2 | 4 | 18 | 11 | 3 |

| Tumor differentiation | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 1,204 | 66 | 26 | 12 | 11 | 61 |

| Moderately differentiated | 388 | 21 | 23 | 18 | 17 | 22 |

| Poorly differentiated | 226 | 13 | 51 | 70 | 72 | 17 |

| Tumor depth | ||||||

| Dermis | 1,630 | 90 | 21 | 15 | 16 | 85 |

| Fat | 145 | 8 | 28 | 27 | 22 | 10 |

| Fascia | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Muscle | 29 | 2 | 30 | 37 | 33 | 4 |

| Soft tissue beyond muscle | 2 | 0 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Cartilage | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Bone | 4 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 17 | 1 |

| Unknown | 5 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| PNI, mm | ||||||

| None | 1,744 | 96 | 72 | 67 | 61 | 94 |

| < 0.1 | 37 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| ≥ 0.1 | 32 | 2 | 11 | 18 | 22 | 3 |

| Present, nerve diameter unknown | 5 | 0 | 8 | 12 | 17 | 1 |

Abbreviations: CSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; DSD, disease-specific death; LR, local recurrence; NM, nodal metastasis; OD, overall death; PNI, perineural invasion.

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses

Results of univariable and multivariable analysis of risk factors associated with the development of LR, NM, DSD, and OD are shown in the Data Supplement.

Validation of the BWH T Staging System

This study showed the same four risk factors to predict end points of interest on multivariable analysis as in our prior study (tumor diameter ≥ 2.0 cm, poorly differentiated histology, perineural invasion, and tumor invasion beyond fat)20 (see the Data Supplement). For the perineural invasion risk factor, four LRs and no NMs or DSDs occurred in the 37 patients with small-caliber nerve invasion (< 0.1 mm). Conversely, in the group with large-caliber nerve invasion (n = 32), there were five LRs, six NMs, and four DSDs. Thus, only large-caliber nerve invasion was considered a risk factor in the BWH staging system, whereas this diameter distinction could not be made in the prior study because of small numbers of patients with perineural invasion. Otherwise, BWH staging is the same as our previously published alternative staging system.

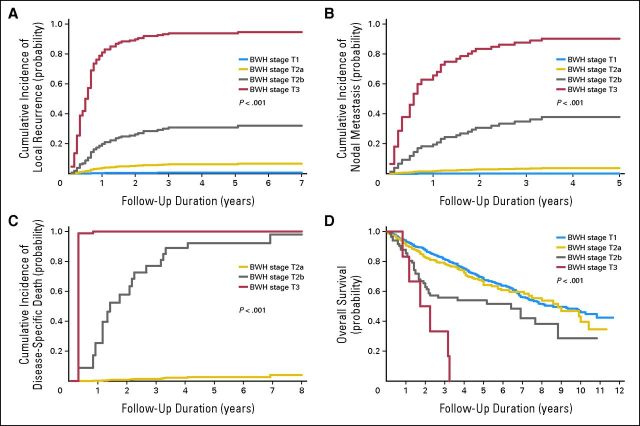

Table 3 shows that 10-year cumulative incidences of end points of interest by BWH T stage are similar compared with those in the prior study. Point estimates are lower and CIs are narrower in this study, as expected, because this study has a larger and broader cohort of patients with CSCC than the initial study. Figure 1 presents the cumulative incidence and Kaplan-Meier curves for each outcome of interest by BWH T stage.

Table 3.

Evaluation of Staging System Distinctiveness: 10-Year CIN of Tumor Outcomes by AJCC, UICC, and BWH T Stages

| T Stage | No. of Tumors | LR |

NM |

DSD |

OD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-Year CIN (%) | 95% CI | 10-Year CIN (%) | 95% CI | 10-Year CIN (%) | 95% CI | 10-Year CIN (%) | 95% CI | ||

| AJCC | |||||||||

| T1 | 1,361 | 0.7 | 0 to 1 | 0.1 | 0 to 1 | No events | 32 | 29 to 34 | |

| T2 | 447 | 8 | 5 to 10 | 6 | 4 to 9 | 6 | 4 to 9 | 37 | 32 to 41 |

| T3 | 3 | 67 | 21 to 94 | 67 | 21 to 94 | 100 | 44 to 100 | 100 | 44 to 100 |

| T4 | 3 | 67 | 21 to 94 | 67 | 21 to 94 | 100 | 44 to 100 | 100 | 44 to 100 |

| UICC | |||||||||

| T1 | 1,597 | 2 | 1 to 2 | 1 | 0 to 2 | 0.3 | 0 to 1 | 33 | 31 to 35 |

| T2 | 154 | 7 | 4 to 12 | 3 | 1 to 7 | 3 | 1 to 6 | 31 | 24 to 38 |

| T3 | 43 | 16 | 8 to 30 | 21 | 11 to 35 | 14 | 6 to 27 | 49 | 35 to 63 |

| T4 | 3 | 67 | 21 to 94 | 67 | 21 to 94 | 100 | 44 to 100 | 100 | 44 to 100 |

| BWH, current study | |||||||||

| T1 | 1,393 | 0.6 | 0 to 1 | 0.1 | 0 to 0.4 | No events | 32 | 30 to 35 | |

| T2a | 332 | 5 | 3 to 8 | 3 | 1 to 5 | 1 | 0 to 3 | 32 | 28 to 37 |

| T2b | 86 | 21 | 13 to 27 | 21 | 13 to 27 | 10 | 6 to 19 | 51 | 41 to 58 |

| T3 | 6 | 67 | 30 to 90 | 67 | 30 to 90 | 100 | 61 to 100 | 100 | 61 to 100 |

| BWH, Jambusaria-Pahlajani et al20 | |||||||||

| T1 | 134 | 2 | 1 to 6 | 0.8 | 0.1 to 4 | No events | 27 | 20 to 35 | |

| T2a | 67 | 9 | 4 to 18 | 4 | 2 to 12 | No events | 30 | 20 to 41 | |

| T2b | 49 | 18 | 10 to 31 | 37 | 25 to 51 | 20 | 11 to 34 | 53 | 39 to 66 |

| T3 | 6 | 50 | 19 to 81 | 50 | 19 to 81 | 33 | 10 to 70 | 50 | 19 to 81 |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BWH, Brigham and Women's Hospital; CIN, cumulative incidence; DSD, disease-specific death; LR, local recurrence; NM, nodal metastasis; OD, overall death; T, tumor stage from TNM staging system; UICC, International Union Against Cancer.

Fig 1.

Cumulative incidence function curves for (A) local recurrence, (B) nodal metastasis, and (C) disease-specific death and (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for overall survival by Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) tumor stage.

Comparison of AJCC, UICC, and BWH T Staging Systems

The Data Supplement presents life-table outcome data for LR, NM, DSD, and OD by AJCC, UICC, and BWH T stage. The large majority of tumors were T1 (75% [AJCC], 89% [UICC], and 77% [BWH]). A much smaller fraction were AJCC (25%) and UICC (9%) T2 and BWH T2a (18%). Few tumors were UICC T3 (2%) or BWH T2b (5%). Few tumors met AJCC T3, AJCC T4, and UICC T4 criteria with only three tumors in each of these stages. Similarly, only six tumors were in the highest BWH stage (BWH T3).

Table 3 shows 10-year cumulative incidences for outcomes of interest by T stage system. CIs overlap substantially for AJCC and UICC T3 and T4 for all end points, as do all four UICC stages for the end point of OD, indicating that AJCC and UICC T3 and T4 are not distinct and that UICC staging does not predict OD. BWH T stages have slight overlap of CIs for the end point of OD but otherwise no overlap, indicating good distinctiveness of all four stages for the end points of LR, NM, and DSD. These findings showing distinction between stages were confirmed on pair-wise comparison testing (Gray's and log-rank tests) shown in the Data Supplement.

Homogeneity evaluation of whether outcomes are similar within stages was evaluated by comparing the proportion of poor outcomes occurring in low T stages between systems (Table 4). In AJCC and UICC staging, 86% (95% CI, 77% to 91%) and 70% (95% CI, 61% to 79%) of poor outcomes were clustered in low T stages (UICC and AJCC T1 and T2, respectively). Conversely, in BWH staging, 40% (95% CI, 30% to 49%) of poor outcomes occurred in low T stages (T1 and T2a); most (66%) were LRs. The nonoverlapping CIs indicate that the BWH system had a significantly lower proportion of poor outcomes in low T stages compared with AJCC and UICC systems, thus showing a higher degree of homogeneity. In AJCC and UICC systems, T1 and T2 stages comprise a heterogeneous mix of cases having good but also many poor outcomes.

Table 4.

Evaluation of Staging System Homogeneity and Monotonicity: Proportion of LRs, NMs, and DSDs Occurring in High and Low T Stages by Staging System

| Staging System/T Stage | LR |

NM |

DSD |

Overall Events |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | 95% CI | |

| Evaluation of Homogeneity: Proportion of LRs, NMs, and DSDs Occurring in Low T Stages | |||||||||

| AJCC T1/T2 | 43/47 | 91 | 29/33 | 88 | 12/18 | 67 | 84/98 | 86 | 77 to 91 |

| UICC T1/T2 | 38/47 | 81 | 22/33 | 67 | 9/18 | 50 | 69/98 | 70 | 61 to 79 |

| BWH T1/T2a | 25/47 | 53 | 10/32 | 30 | 3/18 | 17 | 38/98 | 40 | 30 to 49 |

| Evaluation of Monotonicity: Proportion of LRs, NMs, and DSDs Occurring in High T stages | |||||||||

| AJCC T3/T4 | 4/47 | 9 | 4/33 | 12 | 6/18 | 33 | 14/98 | 14 | 9 to 23 |

| UICC T3/T4 | 9/47 | 19 | 11/33 | 33 | 9/18 | 50 | 29/98 | 30 | 21 to 39 |

| BWH T2b/T3 | 22/47 | 47 | 22/32 | 70 | 15/18 | 83 | 59/98 | 60 | 50 to 69 |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BWH, Brigham and Women's Hospital; DSD, disease-specific death; LR, local recurrence; NM, nodal metastasis; T, tumor stage from TNM staging system; UICC, International Union Against Cancer.

Monotonicity (higher proportions of poor outcomes occur at higher tumor stages) was evaluated by comparing the proportion of poor outcomes occurring in high T stages between systems (Table 4). Only 14% (95% CI, 9% to 23%) and 30% (95% CI, 21% to 39%) of poor outcomes occurred in high tumor stages (T3 and T4) for AJCC and UICC systems, respectively. In BWH staging, 60% (95% CI, 50% to 69%) of poor outcomes occurred in high BWH T stages (T2b and T3), including 70% of NMs and 83% of DSDs. AJCC and UICC staging does not consolidate poor outcomes in the upper stages, and thus they are not monotonous systems. BWH staging showed greater monotonicity.

The Data Supplement summarizes the results of McNemar's test for CSCC outcomes by staging system. The results confirm superior homogeneity and monotonicity in the BWH staging system compared with the AJCC and UICC staging systems.

Table 5 summarizes the number of tumors that were upstaged and downstaged by using the BWH T staging system compared with AJCC and UICC staging, and the number of LRs, NMs, and DSDs associated with such changes in stage. Of the 112 tumors that were downstaged from AJCC T2 to BWH T1, there were only two LRs and one NM. Similarly in 56 tumors downstaged from high UICC stage (T2/T3) to low BWH stage (T1/T2a), there was only one LR. In 20 tumors downstaged from high UICC stage (T3) to high BWH stage (T2b), there were four LRs, six NMs, and three DSDs. However, UICC T3 and BWH T2b each represent the third stage in their staging system and thus represent high-stage disease in both systems. These data indicate that tumors downstaged by the BWH system to low-stage disease (BWH T1 and T2) are at low risk for poor outcomes and are thus appropriately downstaged.

Table 5.

No. of Tumors Upstaged and Downstaged Using the BWH T Staging System and Outcomes of Restaged Tumors

| Tumor Staging System | BWH T-Stage Upstaging | No. of Tumors Upstaged | No. of Poor Outcomes |

BWH T-Stage Downstaging | No. of Tumors Downstaged | No. of Poor Outcomes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of LRs | No. of NMs | No. of DSDs | No. of LRs | No. of NMs | No. of DSDs | |||||

| AJCC | T1→T2a | 81 | 2 | 2 | 0 | T2→T1 | 112 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| T1→T2b | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| T2→T2b | 84 | 18 | 18 | 9 | ||||||

| UICC | T1→T2a | 235 | 12 | 7 | 2 | T2→T1 | 43 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| T1→T2b | 37 | 7 | 9 | 3 | T3→T1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| T2→T2b | 29 | 7 | 3 | 3 | T3→T2a | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| T3→T2b | 20 | 4 | 6 | 3 | ||||||

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BWH, Brigham and Women's Hospital; DSD, disease-specific death; LR, local recurrence; NM, nodal metastasis; T, tumor stage from TNM staging system; UICC, International Union Against Cancer.

Table 5 shows that several poor outcomes occurred in tumors that were upstaged in the BWH system, indicating appropriate upstaging by the BWH system. In the 86 cases that were upstaged from low AJCC stage (T1/T2) to high BWH stages (T2b/T3), there were 18 LRs, 18 NMs, and nine DSDs. Similarly, in 66 cases upstaged from low UICC stage (T1/T2) to high BWH stage (T2b), there were 14 LRs, 12 NMs, and six DSDs.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate both UICC and AJCC tumor staging systems for CSCC. The results indicate significant difficulties with current staging. The UICC system has the most poor outcomes in T1 (57% of LR, 52% of NM, and 28% of DSD) and T2 (23% of LR, 15% of NM, and 22% of DSD). T4 cases are rare, with only three of 1,818 tumors in this category. UICC staging relies solely on tumor diameter more than 2 cm to upgrade to T2 and on deep invasion (muscle or beyond) to upgrade to T3 and T4. Thus, many tumors with important risk factors such as poor differentiation and nerve invasion remain in UICC T1, likely accounting for the many poor outcomes occurring in this group.

AJCC 2010 staging expanded T2 and limited T1 by upgrading poorly differentiated, neurally invasive, and deep (> 2 mm or invading beyond papillary dermis) tumors to T2 as well as tumors of the ear or vermillion lip. This moved poor outcomes out of T1. However, because T3 and T4 are reserved for bone invasion, which is rare (in only six of 1,818 tumors herein), the bulk of poor outcomes (72% of LRs, 82% of NMs, 67% of DSDs) occurred in T2 tumors. These difficulties with AJCC staging were noted in our prior study and demonstrated again in this study cohort.20

Such clustering of poor outcomes in low T stages (T1/T2) suggests poor homogeneity and monotonicity and renders T3 and T4 indistinct and inconsequential, limiting the prognostic utility of both UICC and AJCC T staging.

The BWH T staging system was developed with the goal of having a greater proportion of poor outcomes in the higher T stages, which would improve homogeneity and monotonicity with greater separation of high-risk and low-risk tumors. The system is built on the four risk factors significantly associated with at least two CSCC outcomes of interest on multivariable analysis in our two cohort studies. These risk factors (tumor diameter ≥ 2 cm, poorly differentiated histology, depth of tumor invasion beyond fat, and perineural invasion ≥ 0.1 mm) have also been associated with poor outcomes in previous CSCC studies.4–7,9,10,23,24

The BWH tumor staging system divides AJCC T2 tumors into two separate groups; a large low-risk T2a group and a smaller high-risk T2b group, and collapses AJCC T3/T4 (bone invasion tumors) into a single BWH T3 group, which also includes rare high-risk tumors with all four risk factors but no bone invasion. BWH T2b and T3 together account for a small fraction (5%) of CSCCs but a large majority of LRs, NMs, and DSDs (47%, 70%, and 83%, respectively). These figures are similar to our prior study of a smaller higher-risk CSCC cohort in which 57% of LRs, 84% of NMs, and 100% of DSDs occurred in T2b and T3.20 The two lower stages (BWH T1 and T2a) rarely have poor outcomes and a 97% 10-year cure rate. Thus, current treatments appear adequate for this group. Studies of these lower T stages may focus on prevention and cost-effectiveness of different therapeutic modalities.

Conversely, BWH T2b and T3 tumors had a 21% (95% CI, 14% to 31%) and 67% (95% CI, 30% to 90%) risk of NM, respectively. These two stages therefore define a high-risk CSCC group in which nodal staging such as sentinel node biopsy and adjuvant therapy could be considered. Studies of sentinel node biopsy in patients with CSCC indicate that it is safe and has high sensitivity and specificity. More than 20% of patients with high-risk CSCC reported to date have had positive sentinel nodes.12 This is much higher than the 5% to 10% usually reported in melanoma studies, indicating that sentinel node biopsy may be underutilized in high-risk CSCC. Studies evaluating the impact of sentinel lymph node biopsy on CSCC outcomes are needed.

This study is subject to some limitations. The evaluations of UICC, AJCC, and BWH tumor staging systems in this study and our prior study are based on data from academic centers. Although the difficulties with UICC and AJCC staging likely generalize to CSCC at large and these systems have never been validated in a population-based study, the BWH tumor staging system should undergo further validation in a broader, ideally population-based cohort before wide-scale use. The study of molecular and genetic prognostic factors in CSCC is in its infancy, so such factors were not included in this study but may be important in future prognostic models. Although this is the largest study to date of CSCC outcomes, it may have been underpowered to evaluate some potentially important prognostic factors such as immunosuppression. Tumor depth in millimeters was not often recorded on pathology reports, so tissue level of invasion was used as the primary measurement of tumor depth in this study. Future studies may evaluate whether millimeter depth or tissue level of invasion has greater prognostic reliability in CSCC.

Although most CSCCs are easily cured, there is a high-risk subset with an increased risk of metastasis and death. Current UICC and AJCC T staging fail to identify this high-risk subset because the majority of poor outcomes occur in low T stages that comprise heterogeneous tumors with diverse risk profiles. Conversely, the BWH system has four statistically distinct stages and offers increased homogeneity and monotonicity over AJCC and UICC staging, given its enhanced ability to appropriately upstage high-risk tumors from low to high stages, thus consolidating poor outcomes in the upper two stages. Although these two stages make up only 5% of the cohort, they account for the majority (60%) of poor outcomes, including 70% of NMs and 83% of DSDs. In this cohort, the 10-year incidence of LRs, NMs, and DSDs is 24%, 24%, and 16%, respectively, for BWH T2b and T3 tumors. Thus, BWH T2b and T3 tumors make up a high-risk subset of CSCC worthy of further study regarding staging and adjuvant therapy. More work remains to further refine and validate tumor staging systems in CSCC and to define optimal treatment of high-risk tumors.

Supplementary Material

Glossary Terms

- American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM staging:

a cancer staging system that describes the extent of cancer in a patient's body. “T” describes the size of the tumor and whether it has invaded nearby tissue; “N” describes regional lymph nodes that are involved; “M” describes distant metastasis (spread of cancer from one body part to another). The TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours was developed and maintained by the UICC to achieve consensus on one globally recognized standard for classifying the extent of spread of cancer. The TNM classification was also used by the AJCC. In 1987, the UICC and AJCC staging systems were unified into a single staging system. Prognosis of a patient is defined by TNM classification.

- cumulative incidence:

a statistical measure of an event of interest (eg, relapse, death, second malignant neoplasm, a specific disease) occurring in a specified period of time in the population at risk. It is calculated using the formula: (number of new cases of the event of interest)/(total population at risk).

Footnotes

Terms in blue are defined in the glossary, found at the end of this article and online at www.jco.org.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Anokhi Jambusaria-Pahlajani, David P. Harrington, Chrysalyne D. Schmults

Administrative support: Pritesh S. Karia

Provision of study materials or patients: Chrysalyne D. Schmults

Collection and assembly of data: Pritesh S. Karia, George F. Murphy

Data analysis and interpretation: Pritesh S. Karia, Anokhi Jambusaria-Pahlajani, Abrar A. Qureshi, Chrysalyne D. Schmults

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283–287. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Miller CJ, Quon H, et al. Surgical monotherapy versus surgery plus adjuvant radiotherapy in high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review of outcomes. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:574–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:975–983. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103293441306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brantsch KD, Meisner C, Schönfisch B, et al. Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: A prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:713–720. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mourouzis C, Boynton A, Grant J, et al. Cutaneous head and neck SCCs and risk of nodal metastasis: UK experience. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2009;37:443–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmults CD, Karia PS, Carter JB, et al. Factors predictive of recurrence and death from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: A 10-year, single-institution cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:541–547. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brougham ND, Dennett ER, Cameron R, et al. The incidence of metastasis from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and the impact of its risk factors. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:811–815. doi: 10.1002/jso.23155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:957–966. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clayman GL, Lee JJ, Holsinger FC, et al. Mortality risk from squamous cell skin cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:759–765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullen JT, Feng L, Xing Y, et al. Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: Defining a high-risk group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:902–909. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL., Jr Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip: Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:976–990. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross AS, Schmults CD. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: A systemic review of the English literature. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1309–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Hess SD, Katz KA, et al. Uncertainty in the perioperative management of high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma among Mohs surgeons. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1225–1231. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark JR, Rumcheva P, Veness MJ. Analysis and comparison of the 7th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) nodal staging system for metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:4252–4558. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veness MJ, Morgan GJ, Palme CE, et al. Surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy in patients with cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to lymph nodes: Combined treatment should be considered best practice. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:870–875. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000158349.64337.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al., editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. ed 6. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. ed 7. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobin L, Gospodarowicz M, Wittekind C, editors. UICC International Union Against Cancer TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. ed 7. West Sussex, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breuninger H, Brantsch K, Eigentler T, et al. Comparison and evaluation of the current staging of cutaneous carcinomas [in English, German] J Dtsch Dermtaol Ges. 2012;10:579–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2012.07896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Kanetsky PA, Karia PS, et al. Evaluation of AJCC tumor staging for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and a proposed alternative tumor staging system. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:402–410. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalbfleisch DJ, Prentice LR. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. ed 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross AS, Whalen FM, Elenitsas R, et al. Diameter of involved nerves predicts outcomes in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with perineural invasion: An investigator-blinded retrospective study. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1859–1866. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter JB, Johnson MM, Chua TL, et al. Outcomes of primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with perineural invasion: An 11-year cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:35–41. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.