Abstract

Objective:

To identify sociodemographic, clinical, and physician/practice factors associated with deep brain stimulation (DBS). DBS is a proven surgical therapy for Parkinson disease (PD), but is recommended only for patients with excellent health, results in significant out-of-pocket costs, and requires substantial physician involvement.

Methods:

Retrospective cohort study of more than 657,000 Medicare beneficiaries with PD. Multivariable logistic regression models examined the association between demographic, clinical, socioeconomic status (SES), and physician/practice factors, and DBS therapy.

Results:

There were significant disparities in the use of DBS therapy among Medicare beneficiaries with PD. The greatest disparities were associated with race: black (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.16–0.25) and Asian (AOR 0.55, 95% CI 0.44–0.70) beneficiaries were considerably less likely to receive DBS than white beneficiaries. Women (AOR 0.79, 95% CI 0.75–0.83) also had lower odds of receiving DBS compared with men. Eighteen percent of procedures were performed on patients with PD who had cognitive impairment/dementia, a reported contraindication to DBS. Beneficiaries treated in minority-serving PD practices were less likely to receive DBS, regardless of individual race (AOR 0.76, 95% CI 0.66–0.87). Even after adjustment for demographic and clinical covariates, high neighborhood SES was associated with 1.4-fold higher odds of receiving DBS (AOR 1.42, 95% CI 1.33–1.53).

Conclusions:

Among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with PD, race, sex, and neighborhood SES are strong independent predictors of DBS receipt. Racial disparities are amplified when adjusting for physician/clinic characteristics. Future investigations of the demographic differences in clinical need/usefulness of DBS, ease of DBS attainment, and actual/opportunity DBS costs are needed to inform policies to reduce DBS disparities and improve PD quality of care.

Parkinson disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease affecting more than 2 million Americans. Levodopa and dopamine receptor agonists are the mainstays of motor symptom treatment.1 However, disease progression is associated with “motor fluctuations,” temporal shortening of medication response and drug-related involuntary movements. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an important treatment option for those with PD who have nonresponsive motor fluctuations or debilitating tremor. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that DBS provides sustained improvement in motor symptoms, activities of daily living, and quality of life.2–5

PD is a disease of aging and of the aged; however, elderly patients with PD are not well represented in DBS clinical trials, and DBS use in the elderly has not been studied.6,7 RCT-based guidelines recommend excluding those who have evidence of dementia/cognitive impairment—highly prevalent diagnoses in the Medicare PD population.8 DBS requires extensive preoperative testing and frequent outpatient programming visits; DBS treatment costs are not completely covered by Medicare (X. Wang, A.W. Willis, unpublished, 2013). These factors may limit true DBS accessibility for low-income patients or in medically disadvantaged areas.

To address this knowledge gap, we performed a DBS utilization study on almost 690,000 Medicare beneficiaries with PD. We hypothesized that DBS use would be independently influenced by demographic characteristics and whether a diagnosis of dementia/cognitive impairment had been made. We investigated the association of DBS with neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES) and provider characteristics. This study provides real-world data on treatment allocation in the largest US PD population and may identify patient- and system-level barriers to clinically appropriate PD care.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

This study was approved by the Human Studies Committee at Washington University School of Medicine.

Study population.

The study cohort and all variables were derived from 2007 to 2009 outpatient, carrier (physician and institutional), and BASF (Beneficiary Annual Summary File) Medicare research-identifiable files.9 These files contain individual-level demographic (date of birth, race, sex), residential (county, zip code), clinical (ICD-9 and CPT [Current Procedural Terminology] codes), and provider (medical specialty, unique provider number) data. The study population consisted of all Medicare beneficiaries with a PD diagnosis.10 Patients diagnosed with “secondary parkinsonism” (332.1) or “other degenerative diseases of the basal ganglia” (333 or 333.0) were excluded because these diagnoses are a contraindication to DBS.

Patient characteristics.

Standard Medicare codes identified race/ethnicity (white, black, Asian, Hispanic, Native American, other, unknown) and sex. Age was determined using the date of birth. DBS recipients were identified by all CPT codes accepted by Medicare for DBS: neurosurgical therapy (61855, 61862-5, 61867-8, 61885-6, 61880, 61888), intraoperative localization of DBS site (95961-2), pulse generator analysis ± reprogramming (95970, 95972-3, 95978-9), and DBS equipment (E0752, E0754, E0756, E0757, E0758). New DBS treatment patients were defined as those with procedural codes indicating new deep brain electrodes implantation (61855, 61862-3, 61865, 61867) by a neurosurgeon. Patients with claims only containing procedural codes for analysis ± reprogramming were considered preexisting DBS cases.

BASFs contain patient-level data on 21 common comorbid diseases contained in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Chronic Condition Warehouse.11 Chronic Condition Warehouse indicators for diabetes, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, hip fracture, ischemic heart disease, malignancy (breast, colorectal, lung, or endometrial), stroke/TIA, and dementia were used to compare the comorbidity burden in PD-DBS patients with the general PD population and to create an age-weighted modified Charlson comorbidity index that would be used as a covariate in regression analyses.12

Neighborhood SES.

We assigned an SES index score to the beneficiary mailing zip code at the time of the first PD or PD-DBS claim. Zip codes are small geographical areas designed to facilitate mail delivery. Zip Code Tract Areas (ZCTAs) are permanent, US Census Bureau–derived geographical units designed to allow zip code–census data linkage. A ZCTA was assigned to each zip code using Dartmouth Atlas ZTCA–zip code linkage datasets.13 The resulting zip code–level census data were used to calculate a neighborhood SES index score using income, housing value, poverty, education, and unemployment14 variables.

Provider and PD patient population characteristics.

We used carrier files to identify physician specialty and outpatient encounters with physicians specializing in neurology, internal medicine, and family practice. We excluded outpatient visits with other specialists (such as pulmonologists, surgeons, and cardiologists) because we assumed that these had a low relative likelihood of providing the primary management for progressive PD or driving DBS therapy. The unique NPI (national provider identification) number was used to aggregate the following data on Medicare beneficiaries with PD: % white, % minority (= % black + Asian + Hispanic), % 65–74, and % 75+, creating a physician-specific patient population profile. These were transformed into 2 clinic population variables: “minority serving” (= % minority) and “elderly serving” (= % >74 years), which were categorized into tertiles based on the distribution at the physician level.

Analytical methods.

Utilization of DBS (yes/no) was the outcome variable. We compared demographic characteristics, comorbid disease burden, and neighborhood SES score between patients with PD who received DBS (hereto after referred to as PD + DBS) and those who did not. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test, and continuous variables using a t test or analysis of variance, where appropriate.

Multivariable logistic regression models examined differences in DBS utilization according to demographic variables and SES score. Primary models examined patient age, race, sex, and quartiles of SES score separately. Subsequent models adjusted for 1) combined demographic characteristics (race, age, and sex), 2) modified Charlson comorbidity score, and 3) neighborhood SES score. Standard methods were used to produce odds ratios (ORs). All analyses were 2-sided, with p < 0.05 set as the threshold for statistical significance and are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) where appropriate. Statistical analyses were performed using PASW version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

We estimated the likelihood of future DBS associated with PD physician specialty by fitting logistic regression models with new DBS electrode implantation (from 2007 to 2009) as the dependent variable. Our primary models examined new DBS according to physician specialty (neurology vs family practice, neurology vs internal medicine) and across levels of provider characteristics: minority-serving clinic (<33.3% minority PD vs >66.6% minority PD) and elderly-serving clinic (<33.3% older than 74 years vs >66.6% older than 74 years). Additional models were stratified by race/ethnicity to examine the impact of provider characteristics on racial disparities in DBS. All models were adjusted for race, age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index score, and SES score.

We performed several analyses to test the robustness of our primary findings. Our first sensitivity analyses included an indicator for dementia/cognitive impairment. Dementia is a common manifestation of advanced PD, and should limit DBS. The use of DBS in the cognitively impaired may indicate reasonable extension of this treatment to a population that was not well represented in RCTs, or may highlight clinically appropriate underuse of DBS in select demographic groups. Our second sensitivity analyses examined the potential impact of neurologist access. Neurologists are often involved in DBS treatment; however, neurologist distribution varies geographically, calling into question whether geographical access to care can affect utilization.15 To examine this, county-level estimates of neurologist availability were produced by dividing the number of neurologists (calculated from state board registry and Medicare physician data) by the number of elderly Medicare beneficiaries to equal the number of neurologists per beneficiary, similar to the calculation used to identify Health Care Physician Shortage Areas.16 This variable was included to adjust for geographical neurologist shortages. Finally, our data include individuals who had stimulators placed before Medicare eligibility (at age 65 years); therefore, we repeated all analyses restricting analysis to those with new electrode placement.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics.

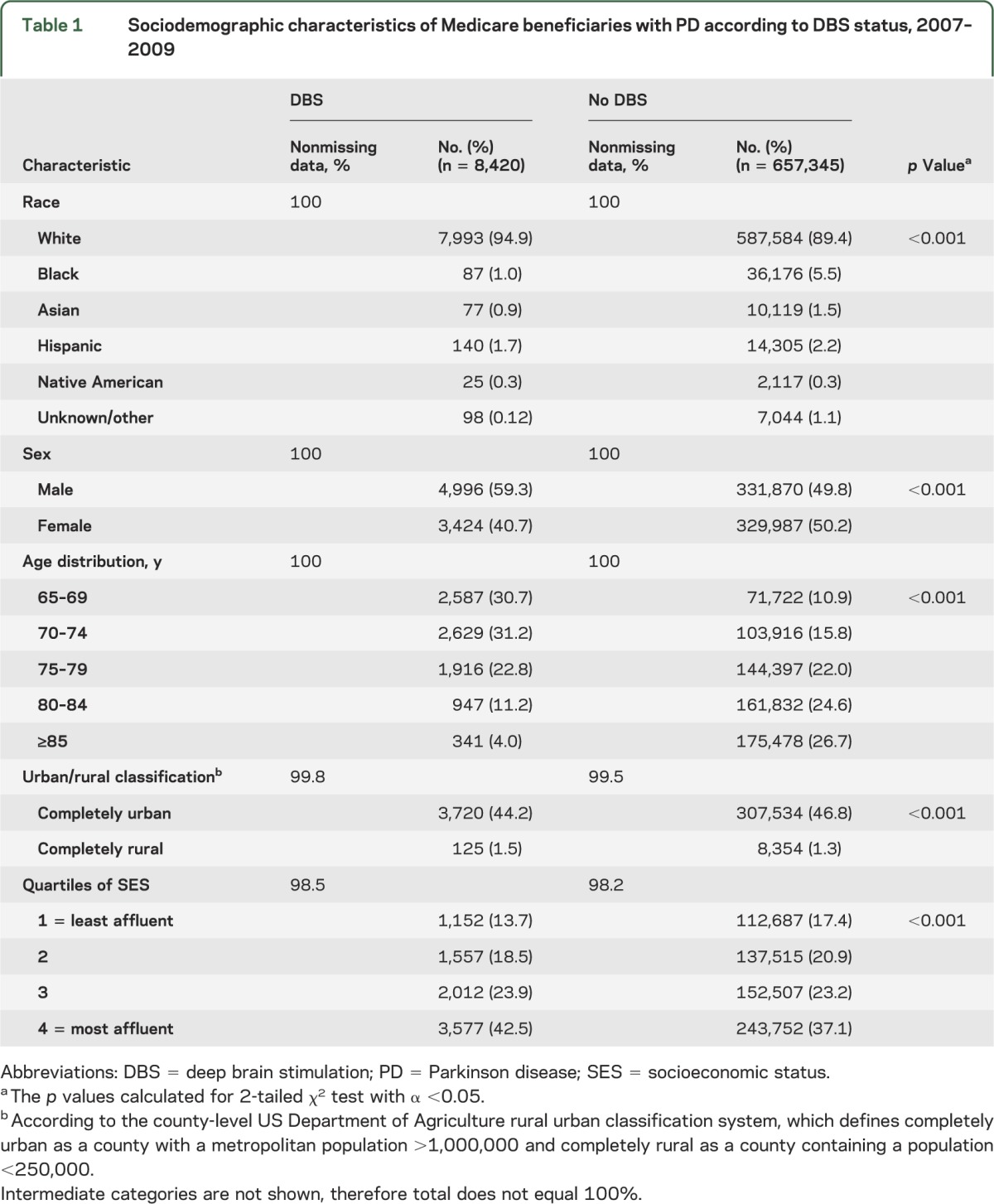

We identified 665,765 beneficiaries with a PD diagnosis between 2007 and 2009; approximately 1% (n = 8,420) of these elderly patients with PD had been treated with DBS. Of these DBS patients, 32.6% (n = 2,752) had a craniotomy with DBS electrode placement. The majority of DBS recipients were white (94.9%, n = 7,993) and male (59.3%, n = 4,996). Although the Hispanic population was nearly equally represented between PD + DBS (2.2%) and non-DBS (1.7%), the black and Asian populations were substantially underrepresented in PD + DBS, each accounting for ≤1.0% of PD + DBS, compared with 5.5% and 1.5% of the non-DBS PD population, respectively (table 1). DBS recipients were younger than the non-DBS PD population (mean age 71.83 years, SD 5.06, vs mean age 78.33 years, SD 6.86; t test p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries with PD according to DBS status, 2007–2009

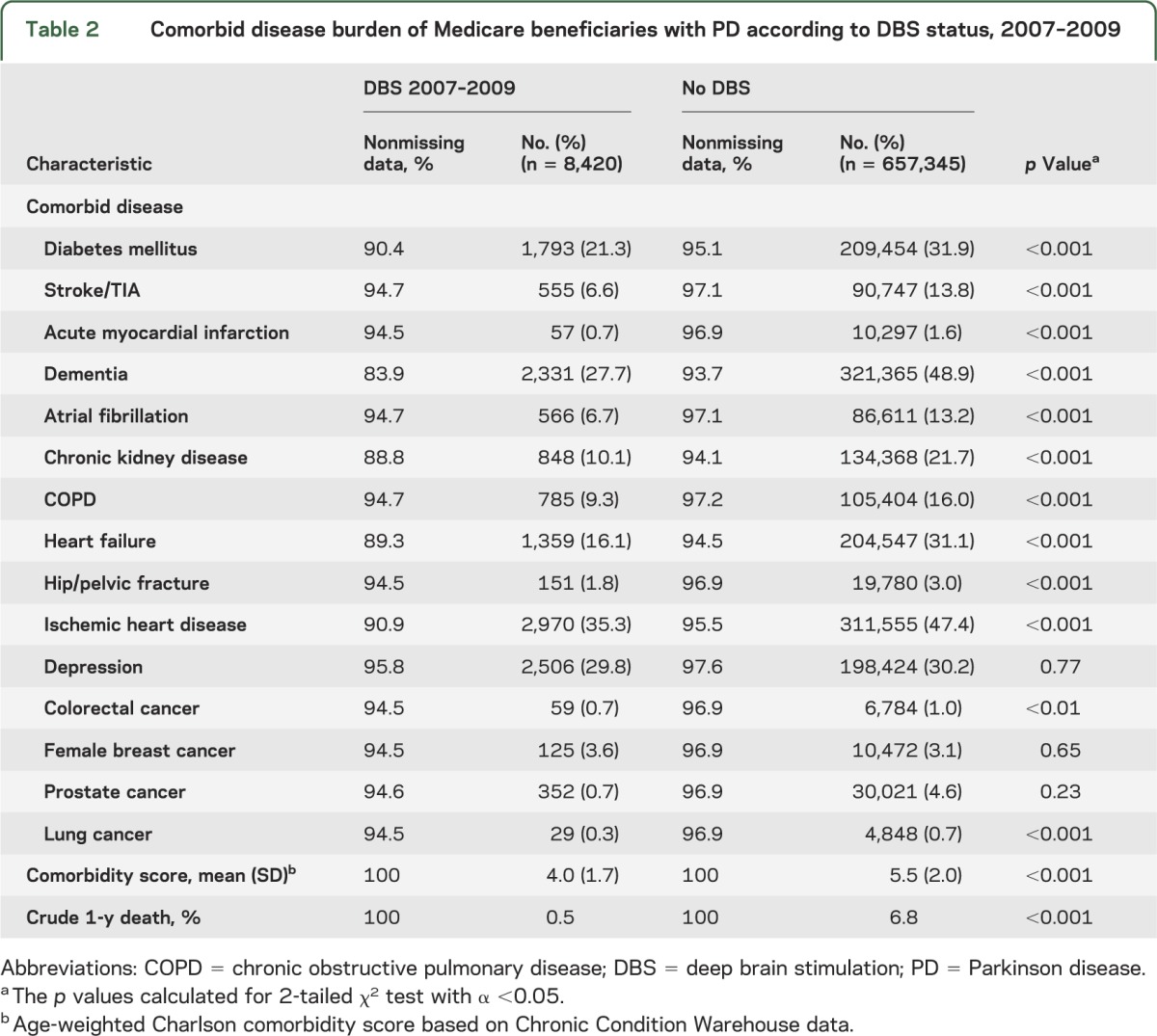

As shown in table 2, common medical problems of the elderly were prevalent in the PD + DBS population: ischemic heart disease (35.3%), depression (29.8%), diabetes mellitus (21.3%), heart failure (16.1%), and chronic kidney disease (10.1%). However, DBS recipients were healthier than their non-DBS counterparts. The PD + DBS group had lower rates of all examined comorbid conditions and a lower crude 1-year mortality rate (PD + DBS 0.05%, vs PD 6.8%; χ2 p < 0.001). A diagnosis of dementia/cognitive impairment was not an absolute contraindication to DBS: 18.5% (n = 508) of new DBS recipients had a perioperative diagnosis of dementia/cognitive impairment.

Table 2.

Comorbid disease burden of Medicare beneficiaries with PD according to DBS status, 2007–2009

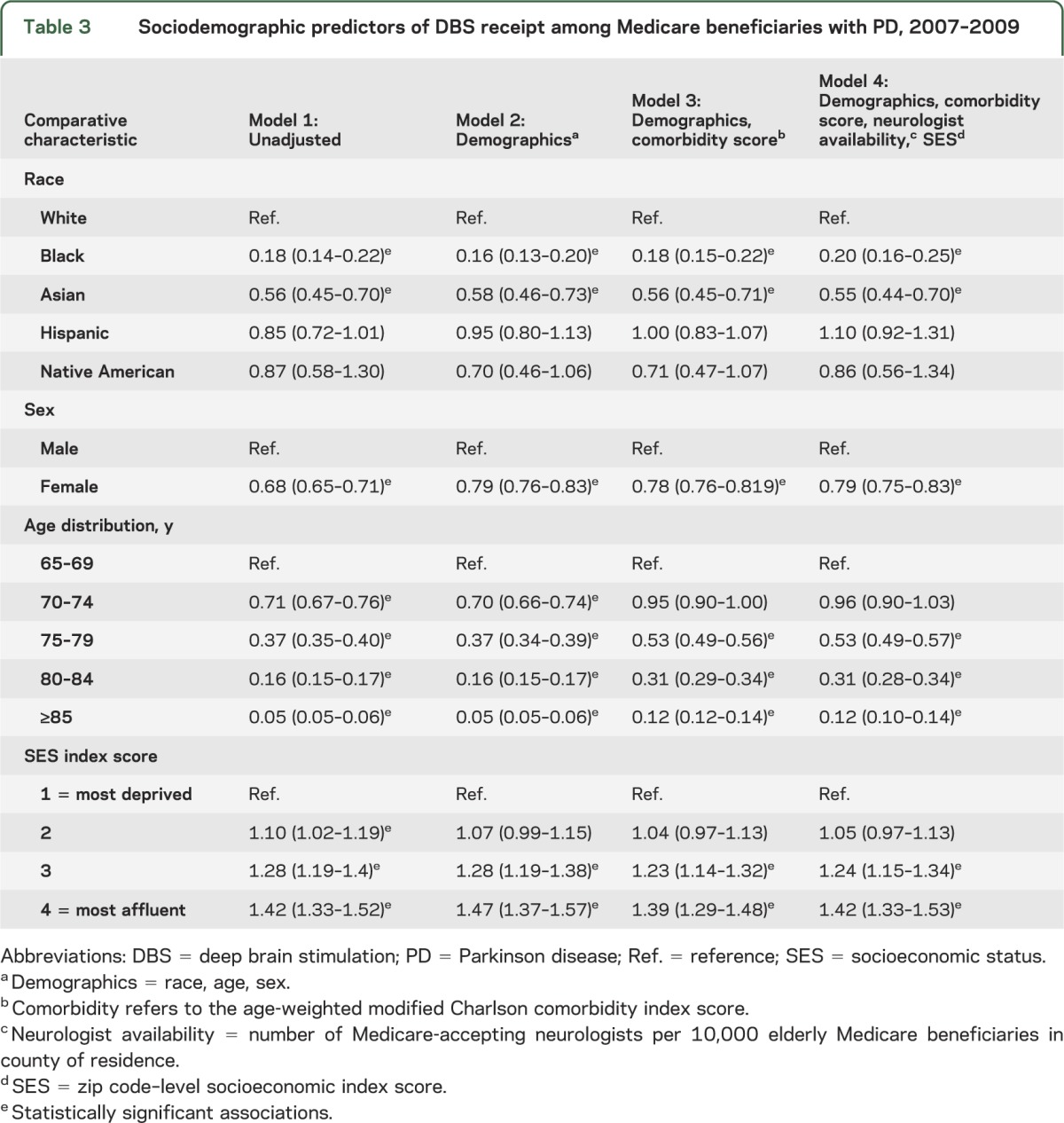

Demographic predictors of DBS.

Race and sex were independent predictors of DBS, and these associations were robust to adjustment for the effects of comorbidity, SES, and neurologist availability (table 3). Black persons had a substantially lower odds of having DBS compared with white persons (adjusted OR [AOR] 0.20, 95% CI 0.16–0.25). Asians were also less likely to have DBS (AOR 0.55, 95% CI 0.44–0.70). There was no difference in DBS use between Hispanic and white populations after adjusting for confounders. Women were less likely than men to receive DBS (AOR 0.79, 95% CI 0.75–0.83).

Table 3.

Sociodemographic predictors of DBS receipt among Medicare beneficiaries with PD, 2007–2009

Adjustment for neurologist availability did not alter the direction or magnitude of our primary findings. Twenty-eight percent (n = 770) of new DBS procedures were performed on patients aged 75 years and older; the remaining were distributed between those aged 65–69 years (37.5%, n = 1,033) and 70–74 years (34.5%, n = 949). Sex and race disparities in new DBS therapy were nearly identical, similar to the overall differences in care shown in table 3; female (AOR 0.71, 95% CI 0.66–0.77), black (AOR 0.18, 95% CI 0.12–0.27), and Asian (AOR 0.70, 95% CI 0.50–0.99) patients with PD had lower odds of new stimulator placement.

SES and DBS.

DBS therapy was more frequently provided to Medicare beneficiaries whose zip code placed them in the top quartile of the SES index, indicating a neighborhood with the highest median income, educational achievement, and median housing values, the least overcrowding, and the lowest proportion of impoverished and unemployed. As shown in table 3, there was a monotonic increase in DBS from the lowest socioeconomic stratum to the highest, which persisted after adjusting for demographic, clinical, and provider access variables (AOR 1.42, 95% CI 1.33–1.52).

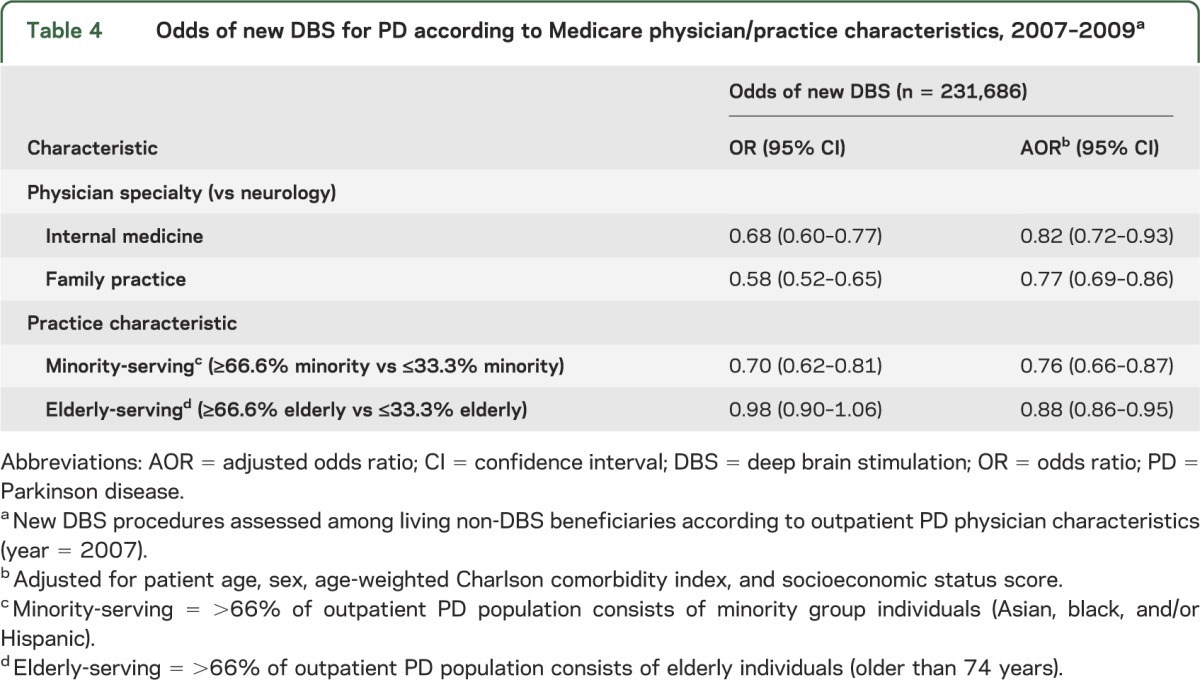

Physician/practice characteristics and DBS.

Physician and practice characteristics likewise predicted whether a beneficiary had a new DBS procedure between 2007 and 2009. Primary care specialist–guided PD treatment was associated with a lower likelihood of new DBS compared with treatment from a neurologist (internist: AOR 0.82, 95% CI 0.72–0.93; family practitioner: AOR 0.77, 95% CI 0.69–0.86). This is not surprising because neurologists may be more likely to manage patients with advanced PD, and neurology has traditionally been the nonsurgical specialty involved in DBS pre- and postoperative care (table 4).

Table 4.

Odds of new DBS for PD according to Medicare physician/practice characteristics, 2007–2009a

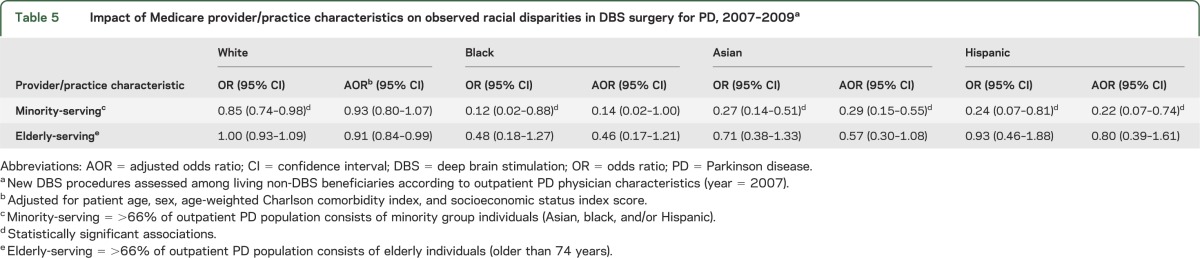

Minority-rich PD practices were less likely than low-minority practices to produce future DBS recipients (AOR 0.76, 95% CI 0.66–0.87). This practice-level disparity transcended individual race in that white patients treated in a minority-rich practice had a lower odds of DBS (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.74–0.98; AOR 0.93, 95% CI 0.80–1.07) when treated in a minority practice, whereas minority patients had further reductions in their odds of DBS. The additional disparity was modest for black patients, but considerable for Asian and Hispanic patients, as shown in table 5. The odds of DBS for these groups approached that of black patients when they were treated in clinic populations mostly comprising fellow minority patients with PD (Asian AOR: 0.29, 95% CI 0.15–0.55; Hispanic: AOR 0.22, 95% CI 0.07–0.74).

Table 5.

Impact of Medicare provider/practice characteristics on observed racial disparities in DBS surgery for PD, 2007–2009a

DISCUSSION

Achieving best practices for PD treatment has become the most important immediate goal since etiologic studies have failed to target a primary preventive measure for PD, and no proven neuroprotective agents are available. The efficacy of DBS is proven, yet this nationwide study of Medicare beneficiaries reveals substantial disparities in DBS use. Asian, black, and female patients with PD are less likely to be treated with DBS than white and male patients. Moreover, elderly beneficiaries with PD living in neighborhoods with lower socioeconomic indicators are less likely to receive DBS, regardless of race or sex. Physician/practice characteristics independently predict DBS, suggesting access barriers despite universal insurance coverage provided by Medicare.

The lower utilization of DBS in black and Asian populations and in women may reflect, in part, a clinically appropriate difference in the need for or usefulness of DBS in those groups. Women and African Americans have the highest prevalence of cognitive impairment/dementia among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with a diagnosis of PD,8 although it is not yet known whether this reflects a different phenotype of PD, concomitant Alzheimer dementia (which predominates among women and African Americans), or dementia due to vascular or metabolic disease. Nonetheless, cognitive impairment is a stated (but apparently not absolute) contraindication to DBS, and reduced use would be expected in groups with high dementia incidence. Black patients with PD have also been found to have more postural instability on initial presentation,17 a motor symptom which may not respond well to DBS, and may be viewed as a relative contraindication to DBS.18 Future prospective studies of these groups are needed to understand how differences in clinical phenotype contribute to patterns of care.

Women and some minorities may also have slower clinical progression, a theory that is indirectly supported by epidemiologic data. The lower risk of PD that has been consistently observed among people of African and Asian descent has been attributed to increased baseline neuromelanin and increased resilience to age-related neurodegeneration.19 Women are also less likely to develop PD (a benefit moderated by early menopause),20,21 and demonstrate via PET higher dopamine transporter binding in the nigrostriatal system than men.22,23 If indicative of bioprotective mechanisms, these groups may experience slower PD motor progression and have reduced need for DBS. Prospective PD cohort studies of women and minorities may identify phenotypic differences that could explain these treatment differences.

We found a robust relationship between DBS use and SES that survived several approaches to reduce confounding by demographic characteristics, health status, and provider access. Socioeconomic gradients in the utilization of complex medical therapies have been demonstrated internationally, across various health systems, and for multiple diseases.24–26 Lower SES is associated with differences in lifelong health behaviors (diet, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption) that can affect comorbid disease severity and functional status at any age.27 The socioeconomic differences in DBS use could reflect surgery prohibitive differences in baseline health status. However, elderly Medicare recipients often face competing demands for their fixed incomes, including out-of-pocket Medicare costs. DBS outpatient and provider costs average $2,200 (2007 dollars) per year, 41% more than non-DBS PD care. DBS out-of-pocket costs would consume 7.2% of median income in the lowest socioeconomic quartile, perhaps limiting the willingness of lower-income seniors to consider DBS. Medical resources and health care quality also vary by SES and limit DBS availability in low SES areas. Therefore, reducing or even eliminating out-of-pocket costs for DBS may not eliminate the socioeconomic disparities we observed.

We found that patients with PD of all races treated by physicians with the highest concentrations of minority patients had at least a 15% lower likelihood of DBS receipt compared with those treated by providers caring for a small percentage of minority patients. This suggests that race disparities in DBS are not solely a result of physician discrimination or minority patient refusal to undergo surgery when offered, although these, plus other social phenomena (physician stereotypes, patient distrust, and poor patient-physician communication) may contribute. Rather, minority patients with PD tend to receive care from providers who are unlikely to perform or refer any of their Medicare beneficiaries with PD for DBS. This may indicate that the multidisciplinary care required for PD is not truly accessible to physicians serving minority-predominant populations. Alternatively, our data may be seen as evidence of the complex interaction among race, SES, and health care access/utilization. While these relationships present research design challenges, because of these interrelations, policy measures that address DBS access and PD care quality for elders with PD who are socioeconomically disadvantaged will benefit other vulnerable groups as well.

Despite our population size and statistically robust findings, there are limitations to our study design. Administrative data have recognized limitations related to coding accuracy and completeness of data.28 Our data do not reflect those who were offered DBS and refused or those who were evaluated but did not qualify for DBS. We also did not know the indication for DBS (motor fluctuations, debilitating tremor) or anatomical target. These may have altered our baseline characteristics. DBS for PD was approved less than 10 years before these study data for primarily those younger than 70 years. This introduces a cohort effect that may influence any age-related conclusions drawn from these data. However, demographic disparities were similar between new and existing DBS treatment groups. Zip code/ZCTA-level socioeconomic data were used as a proxy for individual income and education; this may have introduced measurement error. The need for DBS may vary geographically if environmental risk factors influence motor progression or clinical phenotype. Provider information in Medicare data is limited to physician specialty and practice location. We made no a priori assumptions about the relationship between provider type or practice characteristics and DBS use, or which provider or practice characteristics are most important in PD care. Therefore, we did not adjust our primary models for physician-level clustering. This may result in underestimation of our standard errors. Our analyses included only elderly Medicare beneficiaries and may not be generalizable to younger or non-Medicare patients with PD.

This national study of the elderly Medicare PD population demonstrates that demographic, socioeconomic, and physician/practice factors contribute to disparities in DBS utilization. We identified several sociodemographic groups that could be targeted to improve access to this important PD therapy: older Americans, minorities, women, and the poor. Future studies will investigate clinical progression and phenotype in minorities and women and will use detailed data on physician/practice characteristics and local medical resource availability/quality to determine how system-level differences in care contribute to disparities in individual DBS use. Understanding how neurologic care is currently delivered is essential to the development of evidence-based best practices that optimize patient outcomes and minimize societal and health care costs.

GLOSSARY

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- BASF

Beneficiary Annual Summary File

- CI

confidence interval

- CPT

Current Procedural Terminology

- DBS

deep brain stimulation

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision

- OR

odds ratio

- PD

Parkinson disease

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SES

socioeconomic status

- ZCTA

Zip Code Tract Area

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Allison Willis performed primary data analysis, primary authorship of the manuscript. Dr. Willis had full access to and takes full responsibility for the accuracy of the data. Dr. Mario Schootman provided study design input, manuscript review. Dr. Nathan Kung provided data processing, manuscript revision. Mr. Xiao-Yu Wang provided data processing, manuscript revision. Dr. Joel Perlmutter provided study design input, manuscript review. Dr. Brad Racette provided study design input, manuscript review.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported primarily by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the NIH (K23NS081087), Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grants UL1 TR000448 and KL2 TR000450 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences at the NIH (K24ES017765), and the St. Louis Chapter of the American Parkinson Disease Association. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH and APDA. Other support was provided by Walter and Connie Donius and the Robert Renschen Fund.

DISCLOSURE

A. Willis receives research support from the NIH (K23NS081087), the American Parkinson Disease Association, St. Louis Chapter, Walter and Connie Donius, and the Robert Renschen Fund. M. Schootman receives support from NIH 5R01CA109675-03 (principal investigator [PI]), NIH 5R01CA137750-02 (PI), and NIH 5R01CA112159-05 (PI). N. Kung and X.-Y. Wang report no disclosures. J. Perlmutter serves on the scientific advisory boards of the American Parkinson Disease Association, Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, MO Chapter of the Dystonia Medical Research Fund, Greater St. Louis Chapter of the APDA; serves as an editorial board member of Neurology®; received travel expenses and/or honoraria for lectures or educational activities not sponsored by industry (University of Maryland, Toronto Western Hospital, Long Island Jewish Medical Center, Movement Disorders Society, American Academy of Neurology); received honoraria from Ceregene for travel to lecture; received honoraria from the Parkinson Disease Study Group for grant reviews; and received partial fellowship support for fellows from Medtronic Inc. Dr. Perlmutter receives research support from NIH (1R01 NS41509 [PI], R01 NS050425 [PI], R01 NS058714 [PI], P30 NS057105 [project coleader], NIH/NCRR RR024992 [core leader], R01ES013743 [coinvestigator], R01 NS039821, R01NS058797 [coinvestigator], RO1 HD056015 [coinvestigator], R01 DK085575 [coinvestigator], U54 NS065701 [co-PI and project leader]), receives research support from the Huntington Disease Society of American Center of Excellence, Michael J. Fox Foundation, HiQ Foundation, McDonnell Center for Higher Brain Function, Greater St. Louis Chapter of the American Parkinson Disease Association, American Parkinson Disease Association, and Bander Foundation for Medical Ethics and Advanced PD Research Center at Washington University, and received research support from the Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation. B. Racette received research support from Teva (PI), Eisai (PI), and Solvay (PI); receives research support from Schwarz (PI), Solstice (PI), Eisai (PI), Allergan (PI), and Neurogen (PI); received government research support from NIH (5R01 NS037167-10 [PI, T. Foroud]); receives research support from NIH (U10 NS44455 [PI], R01HG02449 [PI, I. Shoulson], R01 ES013743-01A2 [PI], P42 ES04696 [PI, H. Checkoway], K24 NS060825 [PI], R21 ES017504 [PI], K23 NS43351 [PI]); and received research support from BJHF/ICTS (Neuropathology of Chronic Manganese Exposure [PI]) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fahn S. Levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm Suppl 2006;(71):1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schupbach WM, Maltete D, Houeto JL, et al. Neurosurgery at an earlier stage of Parkinson disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology 2007;68:267–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weaver FM, Follett K, Stern M, et al. Bilateral deep brain stimulation vs best medical therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301:63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams A, Gill S, Varma T, et al. Deep brain stimulation plus best medical therapy versus best medical therapy alone for advanced Parkinson's disease (PD SURG trial): a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:581–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moro E, Lozano AM, Pollak P, et al. Long-term results of a multicenter study on subthalamic and pallidal stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2010;25:578–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krack P, Batir A, Van Blecom N, et al. Five-year follow-up of bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1925–1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deuschl G, Schade-Brittinger C, Krack P, et al. A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med 2006;355:896–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willis AW, Schootman M, Kung N, Evanoff BA, Perlmutter JS, Racette BA. Predictors of survival in patients with Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2012;69:601–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CMS Data Navigator. Available at: https://dnav.cms.gov/. Accessed February 28, 2013

- 10.Wright WA, Evanoff BA, Lian M, Criswell SR, Racette BA. Geographic and ethnic variation in Parkinson disease: a population-based study of US Medicare beneficiaries. Neuroepidemiology 2010;34:143–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse: Data Dictionaries. Available at: https://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/data-dictionaries. 2011

- 12.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dartmouth Atlas Project The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/. Accessed February 28, 2013

- 14.AHRQ. Agency for Healthcare Research Quality. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/. Accessed August 1, 2012.

- 15.Dorsey ER, Willis AW. Caring for the majority. Mov Disord 2013;28:261–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Shortage designation: health professional shortage areas & medically underserved areas/populations. Available at: http://www.hrsa.gov/shortage/. Accessed November 12, 2012

- 17.Dahodwala N, Xie M, Noll E, Siderowf A, Mandell DS. Treatment disparities in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol 2009;66:142–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uitti RJ, Baba Y, Wszolek ZK, Putzke DJ. Defining the Parkinson's disease phenotype: initial symptoms and baseline characteristics in a clinical cohort. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2005;11:139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muthane U, Yasha TC, Shankar SK. Low numbers and no loss of melanized nigral neurons with increasing age in normal human brains from India. Ann Neurol 1998;43:283–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Increased risk of parkinsonism in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology 2008;70:200–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ragonese P, D'Amelio M, Salemi G, et al. Risk of Parkinson disease in women: effect of reproductive characteristics. Neurology 2004;62:2010–2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavalaye J, Booij J, Reneman L, Habraken JB, van Royen EA. Effect of age and gender on dopamine transporter imaging with [123I]FP-CIT SPET in healthy volunteers. Eur J Nucl Med 2000;27:867–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staley JK, Krishnan-Sarin S, Zoghbi S, et al. Sex differences in [123I]beta-CIT SPECT measures of dopamine and serotonin transporter availability in healthy smokers and nonsmokers. Synapse 2001;41:275–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose KM, Foraker RE, Heiss G, Rosamond WD, Suchindran CM, Whitsel EA. Neighborhood socioeconomic and racial disparities in angiography and coronary revascularization: the ARIC Surveillance Study. Ann Epidemiol 2012;22:623–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doubeni CA, Jambaulikar GD, Fouayzi H, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and use of colonoscopy in an insured population: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2012;7:e36392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz SJ, Hofer TP. Socioeconomic disparities in preventive care persist despite universal coverage: breast and cervical cancer screening in Ontario and the United States. JAMA 1994;272:530–534 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doubeni CA, Major JM, Laiyemo AO, et al. Contribution of behavioral risk factors and obesity to socioeconomic differences in colorectal cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:1353–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jollis JG, Ancukiewicz M, DeLong ER, Pryor DB, Muhlbaier LH, Mark DB. Discordance of databases designed for claims payment versus clinical information systems: implications for outcomes research. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:844–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]