Abstract

Study design

Retrospective study of the importance of sacral and sacro-pelvic morphology in developmental L5–S1 spondylolisthesis.

Objectives

To determine and compare the importance of sacral and sacro-pelvic morphology in developmental L5–S1 spondylolisthesis.

Summary and background data

Recent studies have shown abnormalities in sacral and sacro-pelvic morphology in spondylolisthesis. However, it is still unclear if sacral and sacro-pelvic morphology are correlated and if they are equally important in the progression of spondylolisthesis.

Methods

Lateral radiographs of 120 controls and 131 subjects with developmental L5–S1 spondylolisthesis were analyzed. Sacral table angle (STA) and pelvic incidence (PI) were compared using Student t tests. The relationship between STA and PI was assessed separately in the control and spondylolisthesis groups using Pearson’s coefficients. The proportion of subjects with high PI but average STA was compared to the proportion of subjects with low STA but average PI using χ2 tests.

Results

STA was significantly lower and PI was significantly higher in the spondylolisthesis group. STA was statistically related to PI in both control (r = −0.43) and spondylolisthesis (r = −0.57) groups. In the spondylolisthesis group, STA (r = −0.45) and PI (r = 0.35) were significantly related to slip percentage. STA remained statistically related to slip when controlling for PI. A significantly greater proportion of subjects in the spondylolisthesis group had average STA and high PI, rather than average PI and low STA.

Conclusion

The significant relationship between PI and STA validates that geometrically sacral morphology depends on sacro-pelvic morphology. This study failed to demonstrate a clear predominant role of either STA or PI in the presence of spondylolisthesis.

Keywords: Spondylolisthesis, Pelvic incidence, Sacral table angle, Sacro-pelvic morphology, Sacral morphology, Pelvic morphology

Introduction

Several studies suggest the importance of sacro-pelvic and sacral morphology in spondylolisthesis [1–8]. Pelvic incidence (PI), described by Duval-Beaupère’s group [9] (Fig. 1) as a constant sacro-pelvic morphological parameter, has been found to be increased in L5–S1 spondylolisthesis [2, 4–6]. Some studies [4, 6] have also found that PI is related to severity of slip in spondylolisthesis. Similarly, sacral morphology and its relationship to spondylolisthesis has also been reported [1, 3, 5, 7, 8]. In particular, Inoue et al. [3] proposed the sacral table angle (STA) as an important morphological sacral parameter in adult spondylolisthesis (Fig. 2). Another study [7] also showed a significant decrease in STA in pediatric L5–S1 spondylolisthesis as compared to an age- and sex-matched control group, and that the decrease in STA was related to slip grade. Whitesides et al. [8] presented their results from an archeological skeletal study and suggested that STA, rather than PI, may be involved in the etiology of spondylolisthesis.

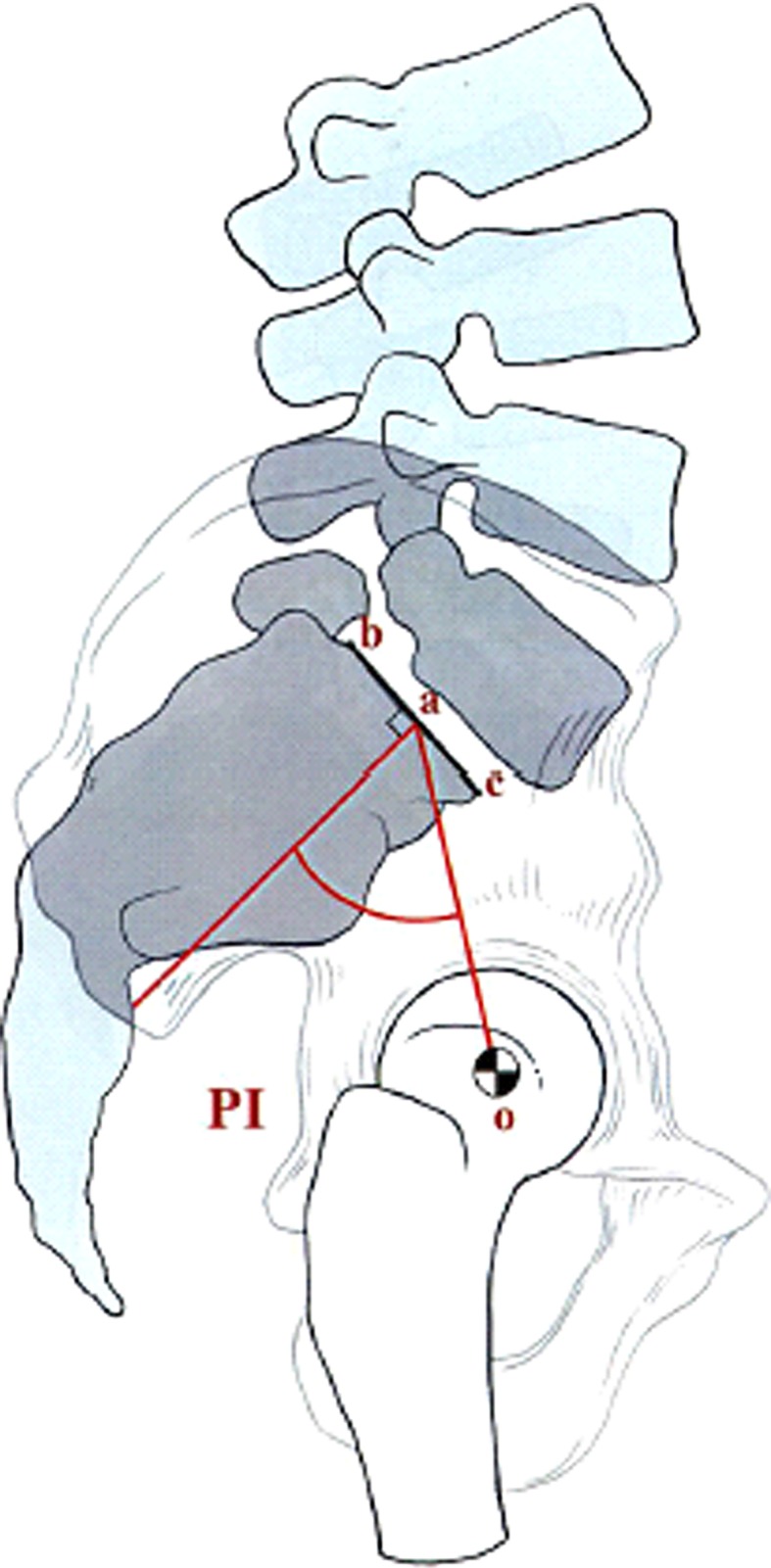

Fig. 1.

Pelvic incidence is defined as an angle subtended by oa which is drawn from the center of the femoral head to the midpoint of the sacral endplate and a line perpendicular to the center of the sacral endplate (a)

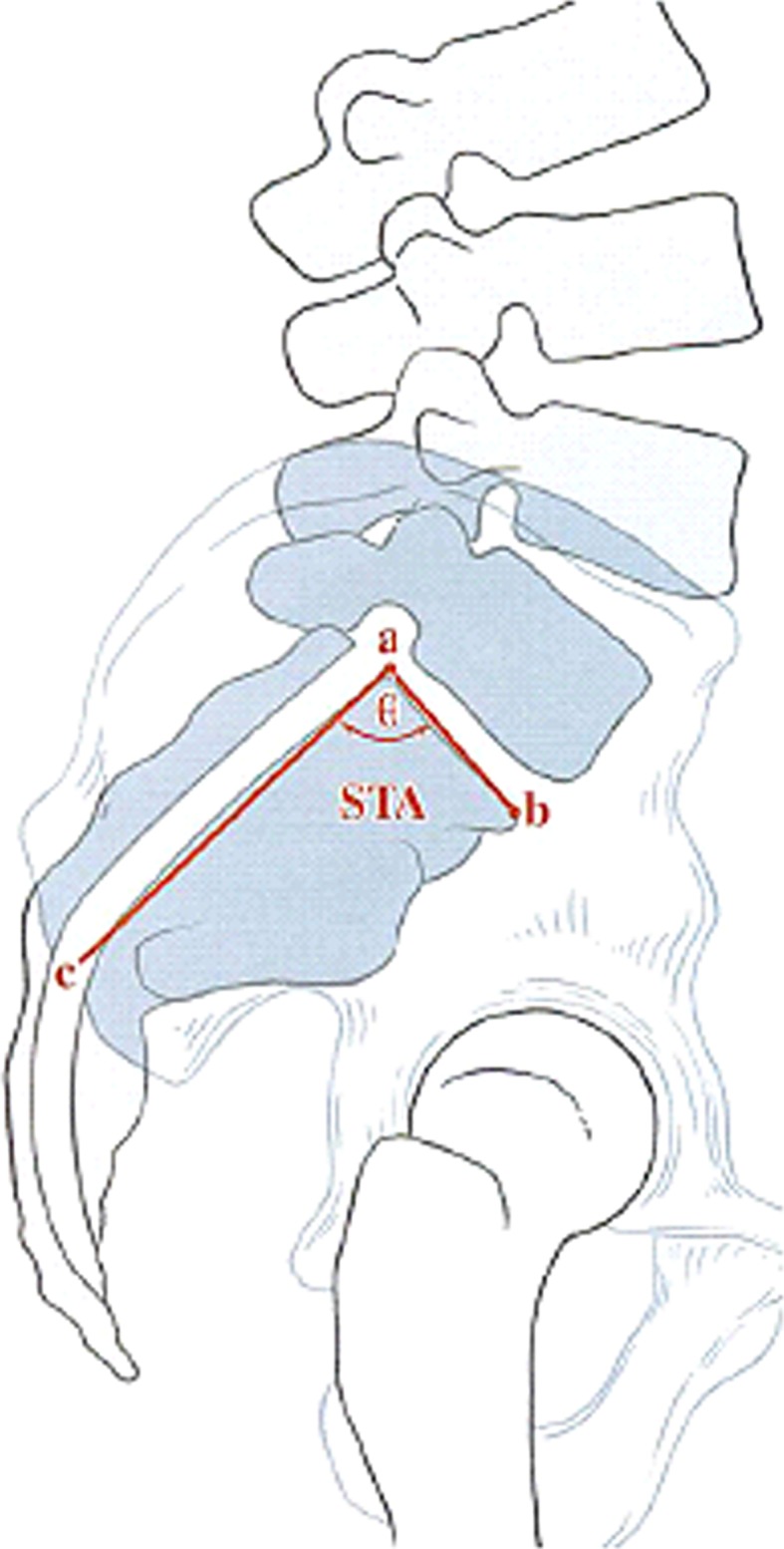

Fig. 2.

Sacral table angle (STA) is the angle subtented by the sacral endplate line ( ) and a line drawn along the posterior aspect of S1 vertebral body (

) and a line drawn along the posterior aspect of S1 vertebral body ( )

)

However, PI depends not only on the position of the sacrum with respect to the femoral heads, but also on sacral morphology. Therefore, as recognized by Whitesides et al. [8], PI should be influenced by STA, which is an anatomical parameter describing sacral morphology. However, the relationship as well as the individual contribution of sacral and sacro-pelvic morphology in spondylolisthesis remains largely unclear. Consequently, it is still unknown whether sacral and sacro-pelvic morphology are equally important and should both be assessed clinically when evaluating spondylolisthesis. The purpose of this work is to evaluate and compare the relative importance of sacral and sacro-pelvic morphology in developmental L5–S1 spondylolisthesis. More specifically, the relationship between the sacral (STA) and sacro-pelvic (PI) morphology in pediatric L5–S1 spondylolisthesis and in a control group, as well as their relationship with slip severity, was investigated. In addition, in order to investigate if the abnormality in STA precedes the abnormality in PI (and vice versa) in spondylolisthesis, subjects with average STA or PI were evaluated separately with the assumption that at the onset of spondylolisthesis, the parameter (STA vs. PI) that is most likely to be more valuable will be abnormal while the other is still normal.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study involves 120 controls and 131 consecutive subjects with developmental L5–S1 spondylolisthesis aged between 7 and 21 years old seen at the spine clinic of a single pediatric institution. A cohort of 120 asymptomatic children and adolescents with no history of previous spine, hip, or pelvis disorders formed the control group. These controls were referred by their primary physician to rule out scoliosis but they all presented with normal physical examination, no history of back pain, and normal radiographs of spine and pelvis. This cohort has been investigated previously in a study on sacral morphology [7]. However, STA measurements were repeated specifically for the current study, explaining the slight but non-significant difference in STA with respect to that previous study. In addition, this study includes measurements for PI that were not performed previously.

A similar radiological protocol was used for all participants, with postero-anterior and lateral digital radiographs of entire spine and pelvis obtained in a comfortable standing position with the knees fully extended. For the upper limbs, the arms were in slight forward flexion while the elbows were fully flexed and the fists were resting on the clavicles as recommended by Faro et al. [10] and Horton et al. [11], in order to minimize postural changes, while allowing adequate visualization of the spine. Using a similar radiological protocol, Labelle et al. [12] were able to confirm that measured PI remained constant on radiographs done before and after surgical treatment of spondylolisthesis, suggesting an adequate clinical reliability for the measurement of PI.

The mean age in the control group was 12.2 ± 3.0 years (range 7–19, male-to-female ratio 0.49). In the spondylolisthesis group, there were 91 low-grade (<50 % slip) and 40 high-grade (≥50 % slip) subjects, with a mean age of 13.7 ± 6.4 (range 7–21, male-to-female ratio 0.48). Age and sex distribution was similar between the two groups.

All radiographs were assessed by the same observer using a custom software (LIO, CHUM Notre-Dame, Montreal, Canada) specifically designed to assess the alignment of the spine and pelvis. Eight anatomical landmarks were identified on the lateral radiograph (antero-inferior and postero-inferior corners of L5 vertebral body; antero-superior, postero-superior, antero-inferior and postero-inferior corners of S1 vertebral body; right and left femoral heads). In the presence of sacral doming, the method recommended by the Spinal Deformity Study Group was used to define the antero-superior and postero-superior corners of S1 vertebral body, corresponding to the two points where the best fit lines along the anterior and posterior borders of the sacrum lose contact with the anterior and posterior borders of S1, respectively [13, 14]. The software automatically computed all three parameters (slip percentage, STA, PI) used in the current study based on the position of identified anatomical landmarks. Percentage of slip was used to assess the severity of spondylolisthesis. It was measured by the translation of the postero-inferior corner of L5 vertebral body with respect to the postero-superior corner of S1 vertebral body and expressed in percentage of length of the superior endplate of S1 vertebral body. Figures 1 and 2 describe the techniques used to measure PI and STA. The inter- and intraobserver reliability of computer-assisted measurements including PI [15] and STA [16] is very high (ICC > 0.9) even in the presence of significant sacral endplate remodeling.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 14.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The level of significance was set to 0.05 in this study for all statistical analyses. In addition to descriptive statistics, STA and PI were compared between control and spondylolisthesis groups using bilateral Student t tests. The correlation between STA and PI was assessed separately in control and spondylolisthesis groups using Pearson’s coefficients. The relationship between morphological parameters (STA and PI) and slip percentage was also assessed using Pearson’s coefficients. Second-order partial correlations were also performed between each morphological variables (STA or PI) and slip percentage, while controlling for the other morphological variable, in order to determine if STA and/or PI are individually related to severity of slip.

Spondylolisthetic subjects with average STA were then assessed separately to evaluate their PI. Similarly, STA of subjects with average PI was evaluated. The abnormality in STA was assumed to precede that in PI when STA was abnormal in the presence of normal PI. Conversely, the abnormality in PI was assumed to precede that in STA when PI was abnormal despite normal STA. The proportion of subjects with high PI and average STA was compared to the proportion of subjects with low STA and average PI using χ2 tests. This analysis was performed twice using two different criteria to identify abnormal STA and PI: (1) greater than one standard deviation from the mean in the control group, and (2) greater than two standard deviations from the mean in the control group.

Results

Slip percentage was 34.3 ± 32.5 % in the spondylolisthesis group. Mean and standard deviation for STA and PI in each group is shown in Table 1. STA was significantly lower (p < 10−16) in this cohort as previously reported [7], while PI was significantly higher (p < 10−23) in the spondylolisthesis group when compared to the control group. Standard deviations were slightly increased in the spondylolisthesis group for both STA and PI.

Table 1.

Sacral table angle and pelvic incidence in the control and spondylolisthesis groups

| Control (n = 120) | Spondylolisthesis (n = 131) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sacral table angle (°) | 94.9 ± 6.8 | 86.1 ± 8.4 |

| Pelvic incidence (°) | 48.2 ± 11.4 | 67.5 ± 14.9 |

STA was significantly related to PI in both control (r = −0.43, p < 10−6) and spondylolisthesis (r = −0.57, p < 10−11) groups. In the spondylolisthesis group, STA was also significantly related to slip percentage (r = −0.45, p < 10−7). The correlation coefficient was smaller between PI and slip percentage (r = 0.35, p < 10−4), but it was also statistically significant. When controlling for PI, STA remained significantly related to slip percentage (r = −0.32, p < 10−3). However, when controlling for STA, PI was no longer correlated with slip percentage (r = 0.14, p = 0.12).

When defining high PI and low STA by a difference greater than one standard deviation from the mean in the control group, STA was considered low when smaller than 88.1° and PI was high when higher than 59.6°. Accordingly in the spondylolisthesis group, there were 60 subjects with average STA and 41 with average PI (p = 0.016). Of those with average STA, 30 (50 %) had a high PI, while 11 (27 %) of those with average PI had a low STA (p = 0.020).

When defining high PI and low STA by a difference greater than two standard deviations from the mean in the control group, STA was considered low when smaller than 81.3° and PI was high when higher than 71.0°. Accordingly in the spondylolisthesis group, there were 96 subjects with average STA and 80 with average PI (p = 0.035). Of those with average STA, 24 (25 %) had high PI, while 7 (9 %) of those with average PI had a low STA (p < 10−2).

Discussion

This study compares the importance of sacral and sacro-pelvic morphology in developmental L5–S1 spondylolisthesis. In accordance with previous publications [2–8], STA and PI were respectively lower and higher in spondylolisthesis when compared to controls. STA directly measures sacral morphology, while PI is a descriptor of sacro-pelvic morphology and attempts to quantify the transition between the lumbar spine and lower extremities. Basically, PI depends on sacral morphology and on the position of the sacrum with respect to the femoral heads. Therefore, as recognized by Whitesides et al. [8], PI should be influenced by STA. Consequently, we found a significant relationship between PI and STA both in the control and spondylolisthesis groups.

While it is commonly believed that the etiology of spondylolisthesis is multifactorial [17, 18], some authors [4, 5, 8, 19] have raised a possible etiologic role of sacral and/or sacro-pelvic morphology in lumbosacral spondylolisthesis. Roussouly et al. [19] hypothesized two different mechanisms of low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis based on sacro-pelvic morphology (PI) and orientation (sacral slope and pelvic tilt). High PI typically associated with high sacral slope should increase the shear stresses at L5–S1 and then induce more tension on the pars interarticularis of L5. On the contrary, smaller PI associated with smaller sacral slope would involve impingement of L5 posterior elements between L4 and S1 during extension, thereby causing a “nutcracker” effect. Based on K-means cluster analysis, Labelle et al. [20] confirmed the existence of two distinct subgroups of patients with low-grade developmental spondylolisthesis based on sacro-pelvis morphology: a subgroup with normal or near normal PI values (<60°) and a subgroup with high PI values (≥60°).

STA has also been proposed as a potential etiological factor for spondylolisthesis [6, 8]. Basically, this parameter measures the orientation between the posterior border of the sacrum and the upper sacral endplate (Fig. 2). If the position of the posterior border of the sacrum (line ac) remains constant within the pelvis, then a smaller STA will be associated with a more vertical upper sacral endplate (line ab), potentially resulting in increased shear stress at the lumbosacral junction. Based on three main arguments, Whitesides et al. [8] instead propose that sacral morphology measured from STA, rather than sacro-pelvic morphology (PI), is involved in the etiology of spondylolisthesis. First, they have found that STA in genetically different populations (Aleut and Arikara) decreased as the prevalence of pars defect increased. Second, STA was significantly lower in the presence of spondylolysis for both archeological populations. Finally, PI did not differ between normal and spondylolytic specimens in one of two populations (Aleut population). However, the limited number of specimens (n = 19) for statistical analysis in that last population may be too small to draw definite conclusions on the potential etiologic role of sacral and/or sacro-pelvic morphology in developmental spondylolisthesis. But more importantly, it is in contradiction with current data [2, 4–6] showing a clear increase in PI in developmental spondylolisthesis. It is questionable whether the Aleut population was subject to specific environmental and biomechanical factors that are different from those encountered today. This is suggested by the absence of sacral doming in their specimens and by the absence of high-grade spondylolisthesis in similar populations [21, 22].

As both STA and PI were abnormal in spondylolisthesis, the current authors assumed that if one of these parameters is more relevant than the other in the development of spondylolisthesis, it is more likely to be abnormal in the presence of a normal value for the other parameter. Independent of the criterion that was used to define abnormal values in STA and PI in the spondylolisthesis group (one vs. two standard deviations from the mean in the control group), the proportion of subjects with normal STA was greater than the proportion of subjects with normal PI. Similarly, a significantly greater proportion of subjects had normal STA and abnormal PI, rather than normal PI and abnormal STA. These results do not support a predominant role of STA over PI in the etiology of spondylolisthesis, as suggested by Whitesides et al. [8] In addition, the etiologic role of STA and PI in spondylolisthesis still remains unclear as STA and PI were normal many subjects.

A “dose–response effect” should also be found before one can suggest a causal relationship between sacral and/or sacro-pelvic morphology and progression of spondylolisthesis. Accordingly, the current study specifically investigated the “dose–response effect” by evaluating the relative influence of STA and PI on the severity of spondylolisthesis. The results showed that STA remained significantly related to slip percentage even after controlling for PI, which supports a possible role of STA in progression of developmental L5–S1 spondylolisthesis once it has occurred. On the opposite, PI was not correlated to slip percentage when controlling for STA. A small STA could potentially lead to abnormal or increased stresses at the upper sacral epiphyseal plate and/or at the pars interarticularis. However, this assumption cannot be fully verified by the current study because it is not known if the abnormality seen in STA is primary or secondary to the appearance of the slip, in which case abnormal stresses at the upper sacral epiphyseal plate would lead to bone remodeling and sacral dysplasia, and subsequent decrease in STA. Also, although statistically significant correlations were found between parameters of sacro-pelvic morphology and slip percentage, they were all smaller than 0.5, reinforcing the fact that the etiology of spondylolisthesis is multifactorial. Although not specifically evaluated in the current study, other anatomical factors such as sacral doming, facet/laminar dysplasia, lumbar wedging, disc degeneration, or spino-pelvic alignment can also have a significant influence on slip percentage.

Conclusion

The exact role of sacral and sacro-pelvic morphology in spondylolisthesis remains unclear mainly because its etiology is multifactorial. Spondylolisthesis involves a heterogeneous group of subjects on which the influence of sacral and sacro-pelvic morphology can vary. Accordingly, this study failed to demonstrate a clear predominant role of either STA or PI in the etiology of spondylolisthesis. A longitudinal study with a large cohort of patients with spondylolisthesis will be necessary in the future to assess the changes in PI and STA over time and determine whether abnormal PI and STA in spondylolisthesis are primary or secondary.

Acknowledgments

This research was assisted by support from the Spinal Deformity Study Group. This research was funded by MENTOR, a training programme of the Canadian Institute of Health Research and by an educational research grant from FREOM and Medtronic Sofamor Danek.

Conflict of interest

None.

Contributor Information

Zhi Wang, Email: spineguy88@gmail.com.

Jean-Marc Mac-Thiong, Phone: +1-514-3454876, FAX: +1-514-3454755, Email: macthiong@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Antonadies SB, Hammerberg KW, DeWald RI. Sagittal plane configuration of the sacrum in spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2000;25:1085–1091. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200005010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanson DS, Bridwell KH, Rhee J, et al. Correlation of pelvic incidence with low and high-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2002;27:2026–2029. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200209150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inoue H, Ohmori K, Miyasaka K. Radiographic classification of L5 isthmic spondylolisthesis as adolescent or adult vertebral slip. Spine. 2002;27:831–838. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200204150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labelle H, Roussouly P, Berthonnaud E, et al. Spondylolisthesis, pelvic incidence and sagittal spino-pelvic balance: a correlation study. Spine. 2004;29:2049–2054. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000138279.53439.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marty C, Boisaubert B, Deschamps H, et al. The sagittal anatomy of the sacrum among young adults, infants, and spondylolisthesis patients. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:119–125. doi: 10.1007/s00586-001-0349-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajnics P, Templier A, Skalli W, et al. The association of sagittal spinal and pelvic parameters in asymptomatic persons and patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord. 2002;15:24–30. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200202000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Parent S, Mac-Thiong J-M, Petit Y, et al. Influence of sacral morphology in developmental spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2008;33:2185–2191. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181857f70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitesides TE, Horton WC, Hutton WC, et al. Spondylolytic spondylolisthesis: a study of pelvic and lumbosacral parameters of possible etiologic effect in two genetically and geographically distinct groups with high occurrence. Spine. 2005;30:S12–S21. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000155574.33693.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duval-Beaupère G, Schimdt C, Cosson P. A barycentremetric study of the sagittal shape of spine and pelvis: the conditions required for an economic standing position. Ann Biomed Eng. 1992;20:451–462. doi: 10.1007/BF02368136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faro FD, Marks MC, Pawelek J, et al. Evaluation of a functional position for lateral radiograph acquisition in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2004;29:2284–2289. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000142224.46796.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horton WC, Brown CW, Bridwell KH, et al. Is there an optimal patient stance for obtaining a lateral 36″ radiograph? A critical comparison of three techniques. Spine. 2005;30:427–433. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000153698.94091.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labelle H, Roussouly P, Chopin D, et al. Spino-pelvic alignment after surgical correction for developmental spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1170–1176. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0713-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Labelle H, Roussouly P, Berthonnaud E, Dimnet J, O’Brien M. The importance of spino-pelvic balance in L5–S1 developmental spondylolisthesis: a review of pertinent radiologic measurements. Spine. 2005;30(6 suppl):S27–S34. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000155560.92580.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mac-Thiong J-M, Labelle H, Parent S, et al. Assessment of sacral doming in lumbosacral spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2007;32:1888–1895. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31811ebaa1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vialle R, Ilharreborde B, Dauzac C, Guigui P. Intra and inter-observer reliability of determining degree of pelvic incidence in high-grade spondylolisthesis using a computer assisted method. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1449–1453. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, Parent S, De Guise JA, Labelle H. A variability study of computerized sagittal sacral radiologic measures. Spine. 2010;35:71–75. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181bc9436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lonstein JE. Spondylolisthesis in children. Cause, natural history, and management. Spine. 1999;24:2640–2648. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199912150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mac-Thiong J-M, Labelle H. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. In: Kim DH, Betz RR, Huhn SL, Newton PO, editors. Surgery of the paediatric spine. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers Inc; 2007. pp. 236–256. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roussouly P, Gollogly S, Berthonnaud É, et al. Sagittal alignment of the spine and pelvis in the presence of L5–S1 isthmic lysis and low-grade spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2006;31:2484–2490. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000239155.37261.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labelle H, Roussouly P, Berthonnaud É et al (2009) Spondylolisthesis classification based on spino-pelvic alignment. Presented at the scoliosis research society 44th annual meeting, San Antonio, USA

- 21.Kettelkamp DB, Wright DG. Spondylolisthesis in the Alaskan Eskimo. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:563–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tower SS, Pratt WB. Spondylolysis and associated spondylolisthesis in Eskimo and Athabascan populations. Clin Orthop. 1990;250:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]