Abstract

Introduction

The authors present 15 cases of congenital scoliosis with lumbar or thoracolumbar hemivertebra in children under 10 years of age (mean age at the time of surgery was 5.5 years). Patients were treated by posterior hemivertebra resection and pedicle screws two levels stabilization or three or more levels stabilization in the case of deformity above or under hemivertebra or for severe curve deformities.

Materials and methods

All operated patients had worsening curves; mean follow up was 40 months. The mean scoliosis curve value was 44° Cobb, and reduced to a mean 11° Cobb after surgery. The mean segmental kyphosis value was 19.7° Cobb, and reduced to a mean −1.8° Cobb after surgery. We did not consider total dorsal kyphosis value as all hemivertebras treated were at lumbar or thoracic lumbar level. No major complications emerged (infections, instrumentation mobilization or failure, neurological or vascular impairment) and only one pedicle fracture occurred.

Results

Our findings show that the hemivertebra resection with posterior approach instrumentation is an effective procedure, which has led to significant advances in congenital deformity control, which include excellent frontal and sagittal correction, excellent stability, short segment arthrodesis, low neurological impairment risk, and no necessity for further anterior surgery.

Conclusion

Surgery should be considered as soon as possible in order to avoid severe deformity and the use of long segment arthrodesis. The youngest patient we treated, with a completed dossier at the end the follow up was 24 months old at the time of surgery; the youngest patient treated by this procedure was 18 months old at the time of surgery.

Keywords: Hemivertebra, Posterior approach lumbar hemivertebra resection, Congenital scoliosis

Introduction

Hemivertebrae are the most frequent case of congenital scoliosis. The segmented hemivertebra has growth potential similar to a normal vertebra, thus creating a wedge-shaped deformity that progresses during spinal growth. McMaster and David [1] found that the degree of scoliosis produced depends on four factors: first, the type of hemivertebra; secondly, its location; thirdly, the number of hemiverterae and their relationship with each other; and finally, the age of the patient. Semi-segmented and incarcerated hemivertebrae usually cause a lesser grade scoliotic curve than fully segmented non-incarcerated hemivertebrae, but can, nevertheless, cause significant deformity. Fully segmented non-incarcerated hemivertebrae have normal growth plates and more often require prophylactic surgical treatment to prevent significant deformity. Hemivertebrae with a counter lateral bar are associated with the worst prognosis, followed by two unilateral hemivertebrae and a single hemivertebra [2]. Previously described surgical procedures include in situ posterior or anterior posterior fusions with or without instrumentation, combined anterior and posterior convex hemiepiphysiodesisis, and hemiarthrodesis and hemivertebra excision with fusion. Fusion in situ, hemiepiphyseodesis and arthrodesis may stop or slow down scoliosis progression. Correction is, however, limited and the only definitive solution is to remove the hemivertebra. Royle [3] first reported the procedure in 1928. In the past two decades, many authors described hemivertebra excision by a combined anterior and posterior approach in one-or-two-stage procedures. Bollini [4] reported a long follow-up in cases of hemivertebra resection by a combined anterior and posterior approach performed in a single stage procedure. Ruf and Harms [5, 6] used a hemivertebra resection by posterior resection only with transpedicular instrumentation in early correction even in very young patients; other authors have more recently described similar procedures [9, 10].

Materials and methods

We treated 15 patients under 10 years of age, 10 male and 5 female, with congenital lumbar and thoracic–lumbar junction scoliosis. All patients were operated by a posterior hemivertebra resection and peduncolar instrumentation. All patients were treated by the same surgeon using this technique from 2006 onwards. Mean age at the time of the procedure was 5.5 years (2–9.5 years), mean Cobb value of the main scoliosis curve was 44° (26°–55°), and mean segmental kyphosis value was 19.7° Cobb (10°–27°).

We did not consider total dorsal kyphosis value because all hemivertebras treated were at lumbar or thoracic lumbar level; moreover, there is no evidence of kyphosis deformities in our patients. Finally, sagittal contour in younger patients is rather variable and not fully developed: 13 children in our series were under 6 years of age, so their sagittal contour was not completely defined.

Mean follow up was 40 months (from 27 to 57 months). We treated two patients with hemivertebra at T12–L1 level (one female aged 2 years and 6 months, one male aged 5 years and 6 months), four patients with hemivertebra at L1–L2 level (one male aged 5 years, one female aged 25 months (Fig. 1), one female aged 6 years, one male aged 5 years), three patients with hemivertebra at L2–L3 level (one male aged 4 years and 6 months, one male aged 5 years, one male aged 5 years and 6 months), three patients with hemivertebra at L3–L4 level (one male aged 2 years, one female aged 4 years, one male aged 7 years), one patient with hemivertebra at L4–L5 level (one male aged 4 years (Fig. 2), two patients with hemivertebra at L5–S1 level (one male aged 32 months (Fig. 3), and one female aged 9 years and 6 months) (Table 1). In our department, we started treating congenital scoliosis by hemivertebra resection about 25 years ago, by a posterior approach combined with a delayed anterior approach, and compression and stabilization mainly using Harrington instrumentation. From 2006 onwards, we have used a posterior only resection approach. A posterior surgical technique was fully described by Ruf and Harms [5–8]. In our procedure, we removed the hemivertebrae with vertebral decancellation by a posterior approach technique without any handling of the peritoneum. This technique involved the removing of the posterior elements and then the complete removal of hemivertebra body by morselizing. All our patients were screened before surgery by a pediatric test to detect co-existent malformations at urologic, genital, and bowel level (35 % of our patients) and for cardiac or neurologic structures’ involvement. Accurate imaging is necessary prior to the operation: standard anterior–posterior and lateral X-rays of the spine were performed on all our patients. Bending film to evaluate spine flexibility was also conducted, when necessary, especially in the older patients and where curves were more spared. MRIs were performed to evaluate malformations of the cord, of nerve roots, of the dural sac and to evaluate the presence of vertebral canal malformation. We did not routinely study our patients by CT scan as the MRI was sufficient in most cases to define the deformity visualizing discs, bone, and nervous structures [6]; only in selected cases, where plain X-rays and MRI were unable to show up the anatomy deformity, did we perform a CT scan with 3D reconstruction. By limiting CT scan use, we reduced patients’ exposure to ionizing radiation; this is one of our policies and goals when treating young children.

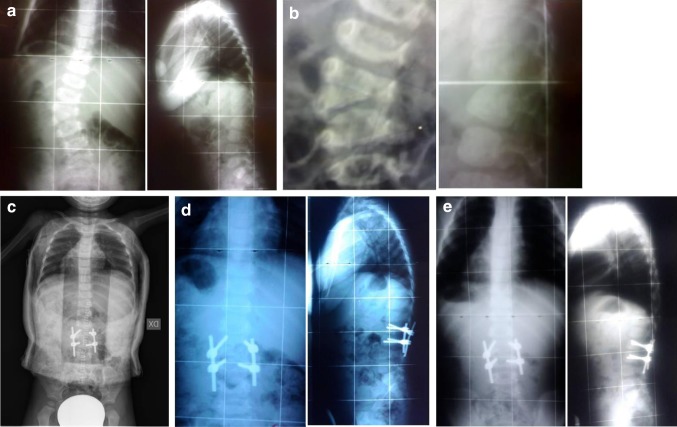

Fig. 1.

Female aged 25 months, L1–L2 hemivertebra. a AP LL X-rays, b AP LL X-rays detail, c AP X-rays after surgery in brace, d AP LL X-rays 1 year follow up, e AP LL X-rays 4 years follow up

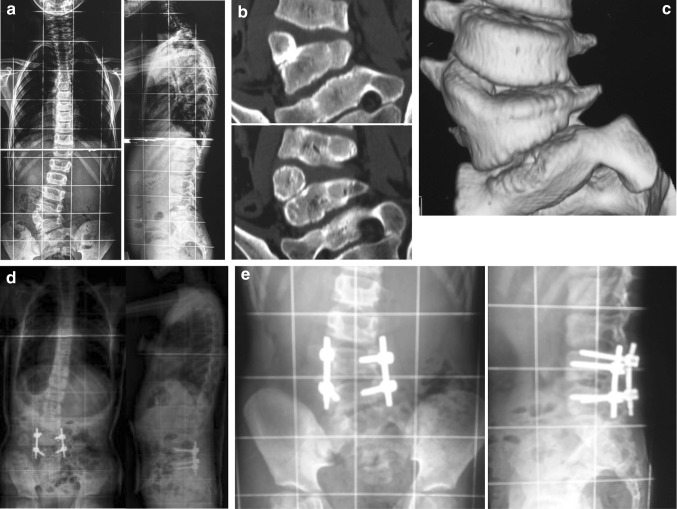

Fig. 2.

Male aged 4 years, L4–L5 hemivertebra, a AP LL X-rays, b CAT scan detail, c CAT scan 3D reconstruction, d AP LL X-rays after surgery in brace, e AP LL X-rays detail 3 years follow up

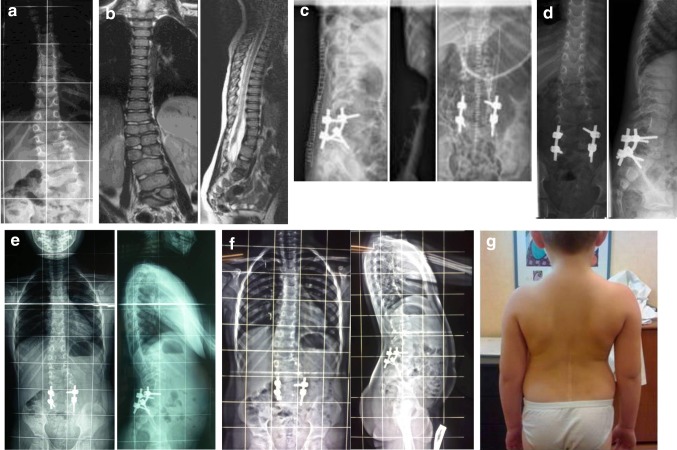

Fig. 3.

Male aged 32 months, L5–S1 hemivertebra, a AP X-rays, b MRI scan, c AP LL X-rays after surgery, d AP LL X-rays 1 year follow up, e AP LL X-rays 3 years follow up, f AP LL X-rays 4 years follow up, g Clinical apparence 4 years follow up

Table 1.

Patients data table

| Patient | Age | Sex | Hemivertebra level | Scoliosis m.c. before surgery | Scoliosis m.c. after surgery | Segmental Kyphosis before surgey | Segmental Kyphosis after surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 years 6 months | F | T12–L1 | 26° | 9° | 10° | 0° |

| 2 | 4 years | M | T12–L1 | 53° | 12° | 20° | −4° |

| 3 | 5 years | M | L1–L2 | 48° | 10° | 25° | −3° |

| 4 | 25 months | F | L1–L2 | 28° | 9° | 17° | −1° |

| 5 | 6 years | F | L1–L2 | 50° | 10° | 20° | −2° |

| 6 | 5 years | M | L1–L2 | 45° | 10° | 18° | −3° |

| 7 | 4 years 6 months | M | L2–L3 | 40° | 12° | 25° | −1° |

| 8 | 5 years | M | L2–L3 | 54° | 15° | 22° | −1° |

| 9 | 5 years 6 months | M | L2–L3 | 55° | 12° | 24° | −2° |

| 10 | 2 years | M | L3–L4 | 35° | 10° | 10° | 0° |

| 11 | 4 years | F | L3–L4 | 30° | 9° | 14° | −1° |

| 12 | 7 years | M | L3–L4 | 55° | 18° | 25° | −3° |

| 13 | 4 years | M | L4–L5 | 55° | 11° | 27° | −2° |

| 14 | 32 months | M | L5–S1 | 40° | 10° | 13° | −1° |

| 15 | 9 years 6 months | F | L5–S1 | 50° | 12° | 25° | −3° |

In our surgical procedure, the spine is exposed at the level of the hemivertebra and the adjacent vertebrae: posterior elements are carefully exposed at the affected levels, including the lamina, the transverse processes, and the facet joints. The first step is to insert K-wires to mark the pedicle under radioscopy control in order to identify the target hemivertebrae; then, after careful probing we prepare the screws’ insertion above and below the hemivertebrae. Once the screws are inserted, the lamina, the transverse processes, the facet joint, and the posterior part of the pedicle are removed. The spinal cord and the nerve above and below the pedicle of the hemivertebra are identified.

This exposure is performed accurately avoiding any maneuver on peritoneum. The rest of the pedicle is removed and the posterior aspect of the vertebral body of the hemivertebra is exposed. This is facilitated by the fact that the hemivertebra sits on the far lateral side of the convex of the curve while the dural sac usually shifts to the concave side [5]. The discs adjacent to the hemivertebra are cut (depending on whether the hemivertebra is fused, partially fused, or free) and the body of the hemivertebra is morselized, mobilized, and removed.

The remaining disc material of the upper and lower disc spaces is completely removed, and the end plates are debrided down to the bleeding bone. The same vertebral body bone of morselized hemivertebrae is used for arthrodesis. We inserted rod in the convex and concave sides and compression is applied on the convex side and distraction is applied on the concave side: step by step correction is achieved until the remaining open space left by hemivertebra resection is completely closed. We have never inserted cages as we have never experienced difficulties in closing the gap caused by the resection; in our opinion this is due to both the patients’ age and to greater curve plasticity. In the case of a single hemivertebra without bars or without other major structural changes of the contiguous vertebrae only the two vertebrae adjacent to the resected hemivertebra are fused; when necessary one or two additional segments may be included into the fusion, depending on how much the curve is spanned in the spine. In three cases, we extended fusion one level above and two levels below the hemivertebra, while in two cases, the fusion was extended on more than two levels, related to deformity, above and two levels below hemivertebra. We did not use intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring (IONM), because IONM was not available in our institution when the surgery considered in this review was performed. Although we did not use IONM in our patients, no severe neurologic impairment occurred. The average operating time was 200 min (range 120–280 min) and average blood loss was 350 ml (range 200–600 ml).

Results

Our patients had a 40-month mean follow up. All patients were studied by standard X-rays of the spine (anterior–posterior and lateral) at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after procedure, and then every 12 months. The main curve mean value at the follow up was 11° Cobb (range 9°–18° Cobb) and the mean segmental kyphosis value at follow up was −1.8° Cobb (range −4° to 0° Cobb), so we obtained complete elimination of sagittal segmental deformity restoring physiologic lordosis (Table 1). Every patient has been treated by brace after surgery for a mean 10 months (range 9–12 months). We used a cast brace for a mean 4 months (range 3–5 months), followed by a custom-modelled brace. We had no case of major complication (severe neurologic impairment, i.e., permanent sensory or motor deficit, infection, instrumentation failure, visceral, or vascular iatrogenic injury). In one case, we observed a transitory sensitive impairment (paresthesia) on left lower leg in a patient after surgery. This patient presented a neurologic anatomy abnormality, she has double spinal root in a single hiatus at L5 level. This neurologic symptom was completely resolved 2 months after the operation, without further implications. In another case, we observed a pedicle fracture at screw insertion level, which required us to perform the screw insertion one level above; instrumentation was stable at 36 months follow-up and the patient had no pain or deformity and fusion at treated levels was complete.

Discussion

In congenital scoliosis, the indication for surgery depends on the degree of scoliosis at the time of diagnosis and its expected progression. Most hemivertebrae, except for some non-segmented or incarcerated forms [11], have normal growth plates and will therefore create increasing deformity with further growth [5, 6]. Secondary curves will develop to promote trunk equilibration. The goal of the treatment of congenital scoliosis is to achieve a straight spine with a physiologic sagittal profile with as short a fusion segment as possible [12]. Delayed treatment of an advanced deformity in older children or adults, however, has to include the secondary structural curves and therefore requires long fusion segments. In addition, correction of these rigid curves is more difficult and associated with a higher risk of neurologic impairment [12]. We have not used IONM during surgery, as mentioned before. IONM was not available in our institution at the time the surgery considered in this review was performed. We believe that IONM is an important safety support in spine procedure. Early correction in young children requires a less invasive approach and a short and sufficiently rigid instrumentation. In the past decades, several techniques were developed to treat pathologies of the anterior part of the spine by a posterior approach, so it is only natural that this “know how” is applied to the hemivertebra resection [13]. Posterior instrumentation is applied in order to obtain complete deformity correction, by closing the space left open after the resection of the hemivertebra with the use of compression on the convex side associated with the distraction in the curve concavity. Stable fixation using pedicle instrumentation allows excellent correction in the frontal and in the sagittal plane. It is very important to keep the fusion segment in the growing spine as short as possible: any fusion beyond the deformed part should be avoided [6].

Short fusion may increase the risk of new deformity, never in our experience, but minimize the compromise of normal spine development. As described by the other authors above, pedicle screws are better suited to transmit correction force to vertebral bodies of a young child’s spine than other instrumentation systems. Some authors [13] stated that pedicles in young children may not be able to withstand the compressive force needed to close down the resection space, but we never experienced this problem: in our series only one patient (a 25-month-old child) had a pedicle fracture; we rose the screw one level on one side and had no further problems. We never experienced any other pedicle fractures in all the other patients (comprising 12 children under 6 years of age and 1 is 6 years old). In our opinion, the single pedicle fracture was caused by a surgical technique defect and not by the pedicle’s intrinsic weakness, as other authors have reported [13, 20]. In the post-operative follow-up, we experienced no pedicle fractures and no screws mobilization or rods ruptures. We believe that the absence of adverse effects could be due to the use of casts and braces for a mean period of 10 months after surgery [13]. Some authors have expressed concerns claiming that the insertion of screws in the pedicles of very young children could lead to spinal canal growth impairment. No evidence of this phenomenon has emerged in our patients to date [14]. Moreover, very recent specimen reports have shown that the insertion of screws in the growing pedicles do not cause narrowing in the posterior part of vertebral canal and only causes partial impairment in the vertebral somatic area [16, 17]. The spinal canal is fully formed in the first year of life [15, 18] and experimental studies show that pedicle screws insertion does not impair canal growth [16, 17]. In our experience, we treated a patient 24 and 25 months old by posterior resection, one at L3–L4 and one at T12–L1 hemivertebra (Fig. 1). No evidence of vertebral growth impairment or spine canal stenosis emerged at end of the follow up. The youngest patient in our experience treated at 18 months has not been included here because his follow up is incomplete at this stage. We believe, however, that we could perform this procedure after 18 months of age, if the patient’s curve severity requires such action. Modern instrumentation, if correctly applied, is very safe and can be used at every level. Short arthrodesis anterior and posterior segment performed in a patient at a young age minimize the risk of developing crankshaft phenomenon during growth. Kesling et al. [21] have stated that congenital scoliosis anterior growth is difficult to predict and that it is, therefore, not easy to define crankshaft risk factors by growth potential measures (as in idiopathic scoliosis). Further in their paper they show that a very low percentage (15 %) of crankshaft phenomenon occurred out of the 54 congenital scoliosis cases they treated by posterior arthrodesis only and that this phenomenon alone never motivated new surgery. We believe that our positive results regarding the absence of deformity progression after surgery will be confirmed at later follow up stages, when operated patients have reached full skeletal maturity.

Our decision to make a vertebral body decancellation of hemivertebrae by a posterior approach technique without any manipulation on the peritoneum enabled us to avoid double surgical access and was motivated by abdominal and/or urologic problems in about 35 % of the patients (i.e., diaphragmatic herniation, regression caudal syndrome, etc.). In this kind of young patient, who has been previously operated at abdominal/pelvis level, peritoneum manipulation could lead to problems in the postoperative stage. Before 2006, we treated 10 hemivertebra cases by a combined anterior–posterior approach: we have not considered these cases here, as the aim of this paper is not to make a comparison of different techniques. We would like to bring it to our readers’ attention that we found that the access involving peritoneum in these patients with pelvic and abdominal structures manipulation—particularly in patients previously operated for urologic-genital or bowel malformation—could cause peritoneal irritation with peristalsis impairment after surgery. We believe that patient tutorization in cast and brace after surgery allows better fusion results over time. The prolonged tutorization of our patients could explain why we have not experienced any instrumentation failure, whereas other authors reported [13] the necessity of applying other rods.

Conclusion

Hemivertebra resection by posterior approach with transpeduncolar instrumentation is an ideal procedure for early correction in young children. Correction should be performed early, even in very young children [6, 18]. We recommend consideringthis procedure for children from 18 months of age on. Using this strategy, the development of severe local deformities and the development of secondary curves can be avoided: if intervention is delayed until secondary scoliotic curves are structured, it would be necessary to extend instrumented arthrodesis to comprise these curves. Hemivertera resection in a child’s spine that does not present structured secondary curves, leads to high resolution of the deformity, meaning that this operation completely eliminates the cause of deformity progression [19, 20].

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.McMaster MJ, David CV. Hemivertebra as a cause of scoliosis. A study of 104 patients. JBJS B. 1986;68(4):588–595. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.68B4.3733836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMaster MJ, Ohtsuka K. The natural history of congenital scoliosis: a study of two hundred and fifty one patients. J Bone Jt Surg (Am) 1982;64:1128–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royle ND. The operative removal of an accessory vertebra. Med J Aust. 1928;1:467–468. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bollini G, Docquier PL, Viehweger E, Launay F, Jouve JL. Thoracolumbar hemivertebrae resection by double approach in a single procedure. Long term follow-up. Spine. 2006;31(15):1745–1757. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000224176.40457.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruf M, Harms J. Posterior hemivertebra resection with transpedicular instrumentation: early correction in children aged 1 to 6 years. Spine. 2003;28(18):2132–2138. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000084627.57308.4A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruf M, Harms J. Hemivertebra resection by posterior approach. Innovative operative technique and first results. Spine. 2002;27(10):1116–1123. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200205150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruf M, Jensen R, Letko L, Harms J. Hemivertebra resection and osteotomies in congenital spine deformity. Spine. 2009;34(17):1791–1799. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ab6290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shono Y, Abumi K, Kaneda K. One stage posterior hemivertebra resection and correction using segmental posterior instrumentation. Spine. 2001;26(7):752–757. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200104010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Luo Z, Li X, Tao H, Du J, Wang Z. Hemivertebra resection for the treatment of congenital lumbarspinal scoliosis with latero-posterior approach. Spine. 2008;33(18):2001. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817d1d29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galloway GM, Zamel K. Neurophysiologic Intraoperative monitoring in Pediatrics. Ped Neur. 2011;44(3):161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arlet V, Odent TH, Aebi M. Congenital scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 2003;18(9):1255–1256. doi: 10.1007/s00586-003-0555-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jalanko T, Rintala R, Puisto V, Helenius I. Hemivertebra resection for congenital scoliosis in young children. Comparison of clinical, radiographic, and health related quality of life outcomes between the anteroposterior and posterolateral approaches. Spine. 2010;36(1):41–49. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ccafd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedequist D, Ermans J, Proctor M. Three rod technique facilitates hemivertebra wedge excision in young children through a posterior only approach. Spine. 2009;34(6):E225–E229. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181997029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cil A, Yazici M, Alanay A, Acaroglu RE, Surat A. Letters to editor and Ruf M, Harms J in response. Spine. 2004;29(14):1593–1596. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000131219.60687.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papp T, Porter RW, Aspden RM. The growth of the lumbar vertebral canal. Spine. 1994;19:2770–2773. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199412150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeszenszky D (2000) Morphological changes of the spinal canal after placement of pedicle screws in newborn pigs. Scoliosis Research Society Annual Meeting

- 17.Fekete TF, Kleinstuck FS, Mannion AF, Kendik SZ, Jeszenszky D. Prospective study of the effect of pedicle screw placement on development of the immature vertebra in an in vivo porcine model. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:1892–1898. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruf M, Harms J. Pedicle screw in 1 and 2-year-old children: technique, complications and effect on further growth. Spine. 2002;7:E460–E466. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aydogan M, Ozturk C, Tezner M, Mirzanli C, Karatoprak O, Hamazaoglu A. Posterior vertebrectomy in Kyphosis, scoliosis and kyphoscoliosis due to hemivertebra. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2008;17(1):33–37. doi: 10.1097/01.bpb.0000218031.75557.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang G, Shengru W, Qiu G, Yu B, Yipeng W, Luk DKK (2011) The efficacy and complications of posterior hemivertebra resection. Eur Spine J. Online ahead of pub [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Kesling KL, Lonstein JE, Denis F, Perra JH, Schwender JD, Transfeldt EE, Winter RB. The crankshaft phenomenon after posterior spinal arthrodesis for congenital scoliosis. A review of 54 patients. Spine. 2003;28(3):267–271. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000042252.25531.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]