Abstract

Many biobanks were established as biorepositories for biomedical research, and a number of biobanks were founded in the 1990s. The main aim of the biobank is to store and to maintain biomaterials for studying chronic disease, identifying risk factors of specific diseases, and applying personalized drug therapies. This report provides a review of biobanks, including Korean biobanks and an analysis of sample volumes, regulations, policies, and ethical issues of the biobank. Until now, the top 6 countries according to the number of large-scale biobanks are the United Kingdom, United States, Sweden, France, the Netherlands, and Italy, and there is one major National Biobank of Korea (NBK) and 17 regional biobanks in Korea. Many countries have regulations and guidelines for the biobanks, and the importance of good management of biobanks is increasing. Meanwhile, according to a first survey of 456 biobank managers in the United States, biobankers are concerned with the underuse of the samples in their repositories, which need to be advertised for researchers. Korea Biobank Network (KBN) project phase II (2013-2015) was also planned for the promotion to use biospecimens in the KBN. The KBN is continuously introducing for researchers to use biospecimens in the biobank. An accreditation process can also be introduced for biobanks to harmonize collections and encourage use of biospecimens in the biobanks. KBN is preparing an on-line application system for the distribution of biospecimens and a biobank accreditation program and is trying to harmonize the biobanks.

Keywords: biobank, bioethics, biospecimens, safety

Introduction

Biobanks provide important materials for many research realms, such as biomarker development for the early diagnoses of specific diseases, including cancer and genetic diseases, and for applying personalized drug therapies. There is no consensus definition for a biobank, but it is considered a biorepository that stores biospecimens for use for diagnostic or research purposes. Also, a biobank is an institution that collects, stores, processes, and uses biological materials, genetic data, and associated epidemiological data from human beings or distributes them to researchers [1]. The term "research biobank" means a collection of human biological material and data obtained directly by the analysis of this material, which is used or is to be used for research purposes [2]. A repository is defined as an organization, place, room, or physical entity that may receive, process, store, maintain, and/or distribute specimens, their derivatives, and their associated data. In this paper, we provide a review of biobanks, including Korean biobanks and an analysis of sample volumes, regulations, policies, and ethical issues of the biobank.

Biobanks around the World

The oldest biobank for the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), funded by the National Institute of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH-NHLBI), collects blood samples and data and was established in 1948. The purpose of the Framingham program was the development of case-finding procedures. A total of 5,209 persons between the age of 30 and 62 from Framingham, Massachusetts participated in this study, and three generations of participants (for a total of almost 15,000 participants) were recruited; the researchers began clinical examinations and lifestyle-related interviews to seek risk factors related to cardiovascular disease (CVD) development. FHS has revealed the significant identification of the main CVD risk factors, such as high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, smoking, and obesity, as well as immense information on factors, such as blood triglyceride and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, age, and so on [3].

By the late 1990s, scientists realized that some diseases originated from a single defective gene, but most genetic diseases are caused by multiple genetic factors on multiple genes [4]. For an understanding of whole-genome information of humans, the Human Genome Project (HGP) was begun in 1990, and the human genome was completely released in 2003.

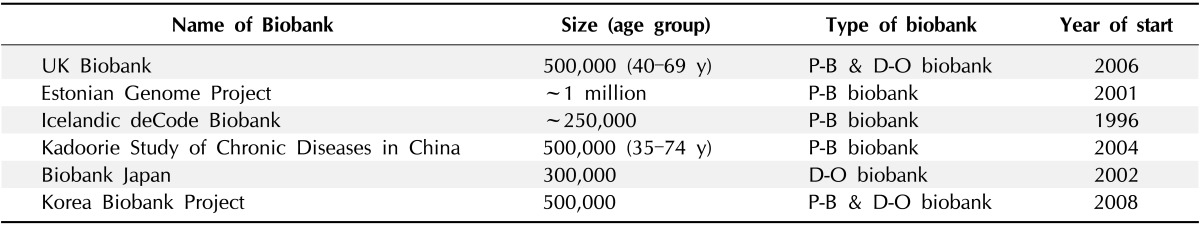

Owing to the increased demands on qualified biospecimens for research, the number of biobanks has increased significantly between 1980 and 1999 worldwide [5]. Many countries, including the European countries, Japan, and Korea, have established large-scale biobanks to collect a large quantity of patient specimens from over 200,000 people, based on their population and/or on their disease-oriented groups (Table 1). Until now, the top 6 countries, according to the number of large-scale biobanks, have been the United Kingdom (n = 15), United States (n = 14), Sweden (n = 12), France (n = 9), the Netherlands (n = 8), and Italy (n = 8). Seventy percent of the world's biobanks are located in Europe. Sixty percent of sponsors for biobanks are governmental or national institutes, and 16% to 17% of biobanks are sponsored by non-profit public service corporations, universities, and hospitals. The number of biobanks is increasing recently, and particularly, 43 biobanks were launched in the 2000s. Most biobanks (60%) recruited less than 100,000 people and thirty percents of the biobanks recruited 100,000 to 1,000,000 people. The number of biobanks collecting blood is 35; 35 collect other biofluids, 43 collect biomaterials, and 16 secure tissue [6].

Table 1.

Biobanks with sample sizes ≥ 200,000 (2012)

P-B, population-based; D-O, disease-oriented.

Source: GBI Research, P3G data, KBN website, Biobank Japan website.

In 2005, the UK Biobank started collecting DNA samples and personal information from 500,000 volunteers aged between 45 and 69 years. The main purpose of the UK Biobank is to look for the relationship between disease, lifestyle, and genes, as well as to identify risk factors that affect individual response to specific drug treatment. The UK Biobank has collected biospecimens from 500,000 people between 2006 and 2010, and they provided their specimens to researchers starting from March 2012 [7, 8]. In 2008, United States researchers stored 270 million specimens in biobanks, and the rate of new sample collection is 20 million per year [9]. In 2009, Time magazine chose biobanking as one of the 10 ideas "changing the world right now" [10]. Elger and Caplan [11] demonstrated that the challenge produced by biobanks is immense: after more than 50 years of classical health research ethics, regulatory agencies have begun to question fundamental ethical milestones.

A new report by Visiongain (http://www.visiongain.com), a business information provider based in London, UK, predicts the world market for biobanking on human medicine will generate $24.4 bn in 2017 and expand strongly to 2023.

In 1995, the Ministry of Education and Science Technology established the Korea National Research Resource Centers for collecting various bioresources. However, the scale and variety of the collections were lacking, because collections were based on an individual research project. The Ministry of Environment established biobanks, but their samples were limited to specimens needed for the research of environmentally induced diseases. Therefore, there was a necessity to establish a biobank that was centered on hospitals for collecting human biospecimens [12].

In 2008, the Ministry of Health and Welfare started the Korea Biobank Project (KBP) and tried to support establishing biobanks within university-affiliated general hospitals as well as creating a network among these biobanks, including National Biobank of Korea (NBK), which is the largest national biorepository in Korea, located in Osong, the central region in South Korea [13, 14]. NBK provides essential biospecimens to scientific researchers by collecting, maintaining, and distributing DNA and serum, plasma, and lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL).

A new building for NBK, the largest in Asia, was constructed in April, 2012 at Osong, Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea. The three-story building, including storage rooms that can contain 26 million vials of biospecimens, was constructed. The structure also has laboratories, an auditorium, and so on. The budget for the project was secured from the Korean central government in 2008, and the construction was started in 2010 and finished in 2012 [14]. Over the years, many biobanks, including 17 regional biobanks, have been established and are moving from a phase of sample collection to open their samples for researches.

Guidelines for Management and Quality Assurance of Biobanks

There are many guidelines for the management of biobanks, such as the International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories (ISBER) guideline and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [15] guideline [16]. ISBER is the largest international forum that addresses the technical, legal, ethical, and managerial issues relevant to repositories of biological and environmental specimens. ISBER has the "Best Practices for Repositories/Collection, Storage and Retrieval of Human Biological Materials for Research." Also, ISBER has introduced standard PREanalytical Coding (SPREC) and can be used in the biobank [17]. In October 2009, the OECD council adapted a recommendation for Human Biobanks and Genetic Research Databases (HBGRDs). The purpose of this recommendation suggests guidelines for the establishment, management, governance, operation, access, use, and discontinuation of HBGRDs, which are structured resources that can be used for the purpose of genetic research. The OECD Best Practice Guidelines for Biological Resource Centers set out further complementary quality assurance and technical aspects for the acquisition, maintenance, and provision of high-quality biological materials in a secure manner.

The standard operating protocols (SOPs), regulations, and management for human biospecimens are important. DNA stability and DNA purity in clinical samples are essential for correct performance and interpretation for diagnosis and research. Generally, quality assurance of human biospecimens consists of a DNA stability test, DNA purity test, microorganism contamination test, and cross-contamination test. All biospecimens collected from the Korea Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) in the case of the NBK underwent a DNA degradation test and purity test. Ten percent of biospecimens stored in NBK were randomly chosen and tested for the quality assurance test to ensure the high quality of DNA extracted from the biospecimens and to check contamination by microorganisms. The quality of DNA is important for genetic research, such as genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and whole-genome sequencing (WGS). In general, pure preparations of DNA and RNA have an OD260/OD280 of 1.8 and 2.0 respectively. LCL quality assurance was also conducted, and 10% of the stocked LCL was randomly selected to undergo survival rate investigation and cross-contamination test in the NBK [13].

Bioethics and Safety in Biobanks

Informed consent is getting a patient to sign a written consent form and is the process of communication between a patient and a medical doctor. In medical diagnosis and treatment, including invasive procedures, a doctor or a researcher must give sufficient information to the patient. Informed consent can be given based on a clear understanding of the process, implications, and consequences of an action. The consent process should include sufficient explanation about how individual information would be handled [18]. The consent process includes the impact of research results on the lives of participants, their families, and their communities [19]. Explanations should be on confidentiality, participants' rights of withdrawal, and specifications [20].

Due to the difficulties of securing specific informed consent, broad consent is a more general form of consent in which individuals agree to have their biosamples and personal information collected and stored in the biobank and for future, unspecified research [21]. Further issues have been discussed recently, such as privacy, confidentiality and data protection, controlling data access, accessibility to biospecimens, benefit sharing, commercialization, intellectual property rights, and genetic discrimination [22].

In order to ensure bioethics and bioethical safety in the life sciences and biotechnologies, each of the institutions should set up its own Institutional Review Board (IRB). When a genetic testing or research institution obtains written informed consent from a test subject concerning the use of specimens for research purposes, it may provide the specimens to either a person conducting research on genes or an institution licensed to open a biobank in Korea [1].

In Korea, the Bioethics and Safety Act was completely revised to reinforce research ethics, including biobanks, and the law took effect in 2013. The number of biobanks within university-affiliated hospitals will increase. This law encourages biobanks to strengthen ethical use of biospecimens, and the law assesses biobanks' responsibility to obtain informed consent from donors and is supervised by the IRB. The law also encourages individual researchers to deposit and use biospecimens at any biobank instead of collecting their own sample collection and distribution processes [1, 14].

Distribution Policy for Biospecimens and Data

Many biobanks have policies for the distribution of biospecimens and data. For example, there is a guideline to distribute biospecimens in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which is a program of studies designed to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States. NHANES's biospecimens are representative samples of Americans and should not be used for the independent case-control study, and 1individual vial must be stored permanently. All proposals for the use of NHANES samples are evaluated by a technical panel for scientific merit and by the NHANES Ethics Review Board (ERB). To determine if this limited resource should be used in the proposed projects, a technical panel will evaluate the public health significance and scientific merit of the proposed research. Distribution of a 0.5-mL sample is available once, and after finishing the research, the remaining samples are abandoned, or remnants more than 0.3 mL should be returned to NHANES; third-party biospecimen transfer is not permitted. Researchers who received specimens must submit the result of the analysis, such as quality control and analytical methods with documents, to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Surplus data without DNA analysis results would be opened in the website and given a period of 3 months for analysis. A researcher's intellectual property rights are not permitted because of research for public health (http://www/cdc/gov/nchs/nhanes.htm).

The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) biorepository in the United States has 2.9 million biological samples, including blood, and researchers can use samples and data through the process of peer review. Researchers can submit summarized proposals to the PLCO, and the chosen research is recommended for full research proposals and submissions are available twice in June/July or December/January annually. The review process takes 4 or 6 months. Researchers with approved proposals should submit IRB approval documents and contract the Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) mutually, and biospecimens are distributed to researchers when approved; researchers should report experimental results to Information Management Systems (IMS) (http://www.plcostars.com).

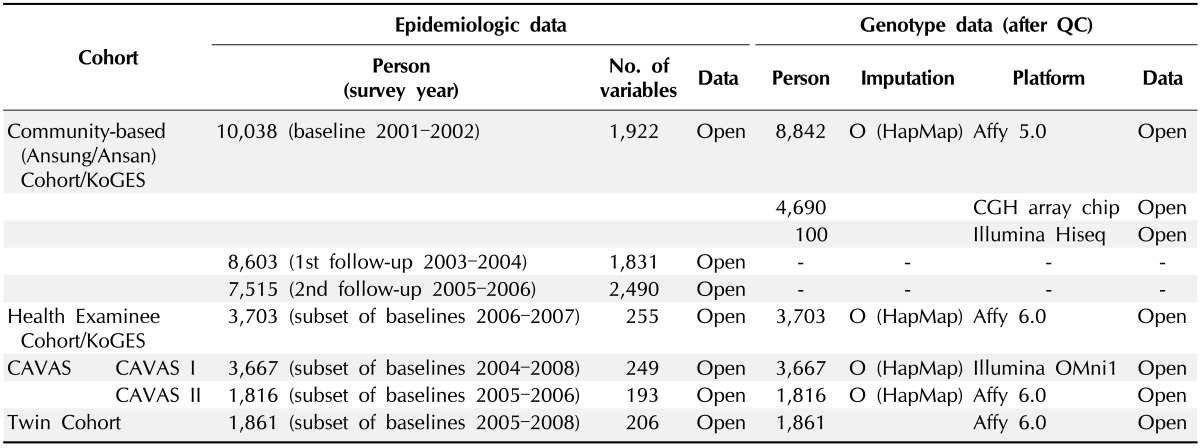

At present, distribution of biospecimens is available to Korean researchers irrespective of research funds, and the distribution for data is accessible to Korean researchers without financial sponsors in Korean biobanks. All proposals for distribution of data and biospecimens should be reviewed and be approved by the IRB belonging to an institute prior to submission. Opened data and biospecimens for distribution in the NBK are shown in Tables 2 and 3. First of all, researchers who want to receive the data and biospecimens have to submit the application document to the NBK. The submitted documents will be reviewed, and a board meeting for distribution is held monthly; distribution of work for the approved application will be performed approximately within one or two months from submission of the application documents for distribution. NBK is planning a website for the distribution process.

Table 2.

Data for distribution ofthe National Biobank of Korea (as of June 2013)

QC, quality control; KoGES, Korea Genome and Epidemiology Study; CAVAS, Cardiovascular Disease Association Study.

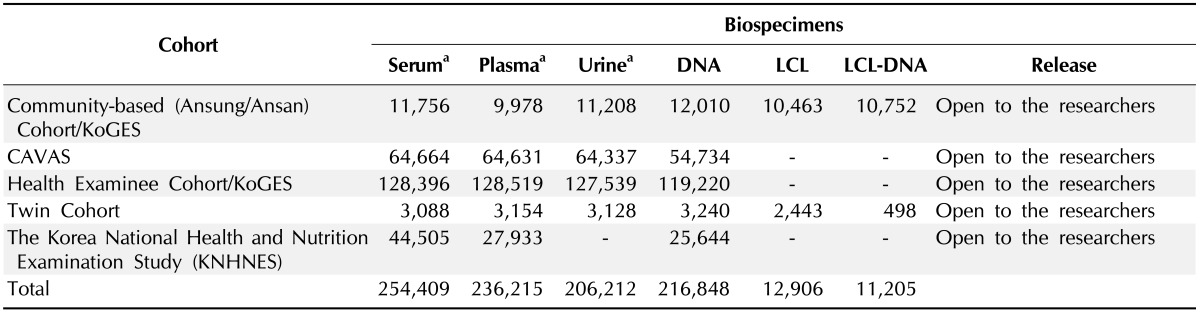

Table 3.

Biospecimens for distribution of the National Biobank of Korea (as of June 2013)

LCL, lymphoblastoid cell line; KoGES, Korea Genome and Epidemiology Study; CAVAS, Cardiovascular Disease Association Study.

aA part of them is being distributed to the researchers.

Most of the distributed biospecimens are DNA samples in the NBK, and a few body fluid samples, including sera and plasma, were distributed. According to the advancement of the technology, the minimum quantity for clinical examination and for the analysis of metabolites is diminishing. However, sera and plasma are very limited resources, and political decisions and long-term planning for the use of body fluid samples will be needed [12].

Studies Using Biospecimens of Biobanks

In 2000, following the HGP, biological research moved into the so-called genomic era. Diseases have been studied by identifying genes and their specific function and understanding the role played by genetics in the beginning and prognosis of diseases, and an advanced world of medicine, known as "personalized medicine," has been initiated [5].

Accessibility to human specimens and data for the purposes of research is important for realms, such as genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, molecular imaging, and nanotechnology [23]. There are genetic factors that affect susceptibility to common diseases [24]. These diseases may have several genetic risk factors that influence each other, and interact with the environment, and this has spurred the development of large-scale biobanking projects to identify susceptible genes [25].

Despite intensive research over the last decade, most of the genetic basis of common human diseases remains unknown. The identification of meaningful genetic variants, genes, and pathways involved in special diseases offers a potential route to new therapies, improved diagnosis, and better disease prevention. For some time, it has been hoped that the advent of GWASs would provide a successful new tool for solving the genetic basis of many of these common causes of human morbidity and mortality.

Advances in sequencing technology enabled us to sequence the whole human genome [26, 27]. The use of WGS of large patient cohorts is a much-needed approach in researching complex traits; it is still being ruled out to detect low-frequency genetic variants, due to its high costs [28, 29].

Among the new and emerging fields of research is proteomics, the study of the full set of proteins encoded by the genome. Also, proteomics is strongly associated with the discovery phase, the first step in the process chain to create diagnostic content [30].

Future Plans for Biobanks, Including the Korea Biobank Network (KBN)

Due to the increased demands on qualified biospecimens for research, the number of biobanks has significantly increased recently. By virtue of the advancements in bioinformatics and biotechnology, storing biospecimens and data on a large scale requires that biobanks harmonize biobank processes and regulations [5].

Most biobanks did their best to secure more biospecimens at the inception of the foundation and comparably distribution rate for the researchers is low. According to a first survey of 456 biobank managers in the United States, nearly 70% of those questioned were concerned with underuse of the samples in their repositories [31]. Therefore, many biobankers are trying to advertise their biospecimens to researchers in regional academic societies. Like the United States, the NBK has faced a similar situation for the underuse of biospecimens stored in the biobank. In the first phase of the KBP (2008-2012), biobanks concentrated on securing facilities, such as storage equipment, as well as securing manpower and funding for biobanks. However, in the second phase (2013-2015), more R&D projects are needed that support clinicians, so that it will be possible to gather resources with more information.

For maximizing the value of biospecimens, consistency in the methods by which they are retrieved, processed, stored, and transported is important. Ideally, this should involve the use of agreed SOPs in general [32]. The other issue in the next big step is automated biobanking, and today's biobanks demand and move toward automated sample management systems that meet the requirements for reliability, sample integrity, high capacity, and high throughput.

Horn, the former director of the Genetic Alliance, demonstrates that biobanks have to cooperate together to achieve their mission, and standardization is going to be important for researchers to get samples from different collections; we need catalogs that say where these samples exist [33]. Accreditation processes can also be introduced to biobanks for harmonizing collections and encouraging use of biospecimens in the biobanks, including the KBN. The NBK is also preparing an online distribution portal for the convenient application of distribution to researchers and preparing a biobank accreditation program; these will harmonize the biobanks in Korea.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affairs. The Bioethics and Safety Act. No. 9100. Seoul: Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affairs; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Norwegian Act Relating to Biobank. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of Public Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawber TR, Kannel WB. The Framingham Study, An epidemiologic approach to coronary heat diseas. Circulation. 1966;34:553–555. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.34.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greely HT. The uneasy ethical and legal underpinnings of large-scale genomic biobanks. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2007;8:343–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.GBI Research. Biobanks: 2011 Yearbook. Survey Report. GBI Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minamikumo M. Current status and future of biobanks. Policy Inst News. 2012;36:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watts G. UK Biobank opens it data vaults to researchers. BMJ. 2012;344:e2459. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UK Biobank. The UK Biobank project. Biobank. UK Biobank; 2013. [Accessed 2013 Oct 15]. Available from: http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haga SB, Beskow LM. Ethical, legal, and social implications of biobanks for genetics research. Adv Genet. 2008;60:505–544. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(07)00418-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park A. 10 ideas changing the world right now. Biobanks. TIME. 2009 Mar 12; Part 8.

- 11.Elger BS, Caplan AL. Consent and anonymization in research involving biobanks: differing terms and norms present serious barriers to an international framework. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:661–666. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. An Internal Report of Project Implementation from Regional Biobanks. Cheongwon: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho SY, Hong EJ, Nam JM, Han B, Chu C, Park O. Opening of the national biobank of Korea as the infrastructure of future biomedical science in Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2012;3:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park O, Cho SY, Shin SY, Park JS, Kim JW, Han BG. A strategic plan for the second phase (2013-2015) of the Korea Biobank Project. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2013;4:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Guidelines on Human Biobanks and Genetic Research Databases. Paris: OECD; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories. 2012 best practices for repositories: collection, storage, retrieval, and distribution of biological materials for research. Biopreserv Biobank. 2012;10:79–161. doi: 10.1089/bio.2012.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betsou F, Lehmann S, Ashton G, Barnes M, Benson EE, Coppola D, et al. Standard preanalytical coding for biospecimens: defining the sample PREanalytical code. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1004–1011. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bredenoord AL, Kroes HY, Cuppen E, Parker M, van Delden JJ. Disclosure of individual genetic data to research participants: the debate reconsidered. Trends Genet. 2011;27:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotimi CN, Marshall PA. Tailoring the process of informed consent in genetic and genomic research. Genome Med. 2010;2:20. doi: 10.1186/gm141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaye J, Boddington P, de Vries J, Hawkins N, Melham K. Ethical implications of the use of whole genome methods in medical research. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:398–403. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otlowski M. Developing an appropriate consent model for biobanks: in defence of "broad" consent. In: Kaye J, Stranger M, editors. Principles and Practice in Biobank Governance. Aldershot: Ashgate; 2009. pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGuire AL, Caulfield T, Cho MK. Research ethics and the challenge of whole-genome sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:152–156. doi: 10.1038/nrg2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NCI Best practices for biospecimen resources. Bethesda: National Cancer Institue, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.; [Accessed 2013 Oct 4]. Available from: http://biospecimens.cancer.gov/bestpractices/2011-NCIBestPractices.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otlowski M, Nicol D, Stranger M. Biobanks Information Paper. Canberra: Austrailian Government, National Health and Medical Research Council; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wellcome Trust. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austin MA, Harding S, McElroy C. Genebanks: a comparison of eight proposed international genetic databases. Community Genet. 2003;6:37–45. doi: 10.1159/000069544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knoppers BM, Abdul-Rahman MH. Biobanks in the literature. In: Elger B, Biller-Andorno N, Mauron A, Capron AM, editors. Ethical Issues in Governing Biobanks: Global Perspectives. Aldershot: Ashgate; 2008. pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Day-Williams AG, Zeggini E. The effect of next-generation sequencing technology on complex trait research. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41:561–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diamandis EP. Next-generation sequencing: a new revolution in molecular diagnostics? Clin Chem. 2009;55:2088–2092. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.133389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zolg W. The proteomic search for diagnostic biomarkers: lost in translation? Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1720–1726. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R600001-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scudellari M. Biobank managers bemoan underuse of collected samples. Nat Med. 2013;19:253. doi: 10.1038/nm0313-253a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson GE, Cadigan RJ, Edwards TP, Conlon I, Nelson AG, Evans JP, et al. Characterizing biobank organizations in the U.S.: results from a national survey. Genome Med. 2013;5:3. doi: 10.1186/gm407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Betsou F, Rimm DL, Watson PH, Womack C, Hubel A, Coleman RA, et al. What are the biggest challenges and opportunities for biorepositories in the next three to five years? Biopreserv Biobank. 2010;8:81–88. doi: 10.1089/bio.2010.8210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]