Abstract

The multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2, ABCC2) gene may determine individual susceptibility to adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in the central nervous system (CNS) by limiting brain access of antiepileptic drugs, especially valproic acid (VPA). Our objective was to investigate the effect of ABCC2 polymorphisms on ADRs caused by VPA in Korean epileptic patients. We examined the association of ABCC2 single-nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotype frequencies with VPA related to adverse reactions. In addition, the association of the polymorphisms with the risk of VPA related to adverse reactions was estimated by logistic regression analysis. A total of 41 (24.4%) patients had shown VPA-related adverse reactions in CNS, and the most frequent symptom was tremor (78.0%). The patients with CNS ADRs were more likely to have the G allele (79.3% vs. 62.7%, p = 0.0057) and the GG genotype (61.0% vs. 39.7%, p = 0.019) at the g.-1774delG locus. The frequency of the haplotype containing g.-1774Gdel was significantly lower in the patients with CNS ADRs than without CNS ADRs (15.8% vs. 32.3%, p = 0.0039). Lastly, in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the presence of the GG genotype at the g.-1774delG locus was identified as a stronger risk factor for VPA related to ADRs (odds ratio, 8.53; 95% confidence interval, 1.04 to 70.17). We demonstrated that ABCC2 polymorphisms may influence VPA-related ADRs. The results above suggest the possible usefulness of ABCC2 gene polymorphisms as a marker for predicting response to VPA-related ADRs.

Keywords: drug toxicity, epilepsy, genetic polymorphism, MRP2, valproic acid

Introduction

Various forms of epilepsy are among the most common serious brain disorders and present through convulsion, autonomic movement, impaired consciousness, and more [1]. These neurological disorders affect an estimated 42 million people of all ages worldwide [2]. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) has challenged the treatment of epilepsy, since many antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are not effectively distributed to the vascular endothelium or, accordingly, to their targets in brain [3, 4]. The BBB, thought to be the first-line barrier to the disposition of drug from the blood to the brain [5], consists of the interplay of three major microvascular components. Tight junctions between the endothelial cells constitute the major permeability barrier. The overall biology of the barrier is shaped by the interactions between the endothelium and the pericytes/smooth muscle cells and the astrocyte foot processes that cover most of the abluminal surface of the microvasculature [6].

Drug pharmacokinetics is controlled by drug transporters, which regulate drug absorption, distribution, and excretion. Drug transporters are considered a second-line barrier for limiting drug disposition from the blood to the brain [7]. In brain capillary endothelial cells, multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1); multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1), MRP2, MRP4, and MRP5; and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) are among the many drug transporters that might be expressed at the luminal side of the membrane [5, 8, 9]. MRP2, in particular, is over-expressed (about 225% greater) in drug-refractory temporal lobe epileptic patients with hippocampal sclerosis (HS) [5, 10-12]. Drug reactions can be different between individuals with the same AED blood concentrations and therapeutic levels, because drug distribution is influenced by variable levels of drug transporters. MRP2 is thought to play a more important role in the distribution of AEDs than other transporters in the epileptic brain [13]. MRP2 has been demonstrated to transport many AEDs, including valproate (VPA), carbamazepine (CBZ), phenytoin (PHT), and more [9, 14-17]. Valproic acid has become established as one of the most widely used AEDs in the treatment of both generalized and partial seizures in adults and children and is considered to be a substrate of MRP2 [9, 14-17]. Probenecid, an inhibitor of MRPs, has been shown to increase the concentration of valproic acid in the brain [18]. In animal models, TR- rats (MRP2 knockout) have lower VPA and VPA-glucuronide in their bile than control Wistar rats (which intrinsically express MRP2) [19].

Functional polymorphisms in genes encoding drug transporters can alter AED uptake, cerebral distribution, and efflux, resulting in individual differences in AED concentration and effectiveness and/or the occurrence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Many functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been reported. For example, mRNA expression of the c.1446CG MRP2 genotype was recently revealed to be higher than the c.1446CC genotype in the liver [20]. In addition, the c.2302C > T (exon 18, Arg768Trp) mutation is responsible for Dubin-Johnson syndrome [21, 22]. The c.2302C > T and c.4348G > A genotypes correlate with significantly lower MRP2 protein expression levels compared to wild-type and V417I [21]. The c.1249G > A mutation significantly reduces the amount of MRP2 mRNA in human preterm placentas [23]. The g.-1774delG polymorphism has been linked with toxic hepatitis by our group [24]. In the present study, we investigated the association between the g.-1774delG MRP2 genotype and ADRs of the central nervous system (CNS) in VPA treatment groups.

Methods

Subjects

This retrospective study included 168 epileptic Korean patients who received VPA at Sinchon and Gangnam Severance Hospitals. Forty-one patients demonstrated VPA dose-related ADRs in the central nervous system (dizziness, headache, somnolence, diplopia, dysarthria, tremor, etc.), while the remainder (n = 127) did not. Patients who were diagnosed with chronic active epilepsy, West syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, progressive myoclonic epilepsy, tuberous sclerosis, Sturge-Weber syndrome, hamartoma, or brain tumors were excluded. There were no statistical differences in age, sex, response/non-response, and sclerosis between the two groups.

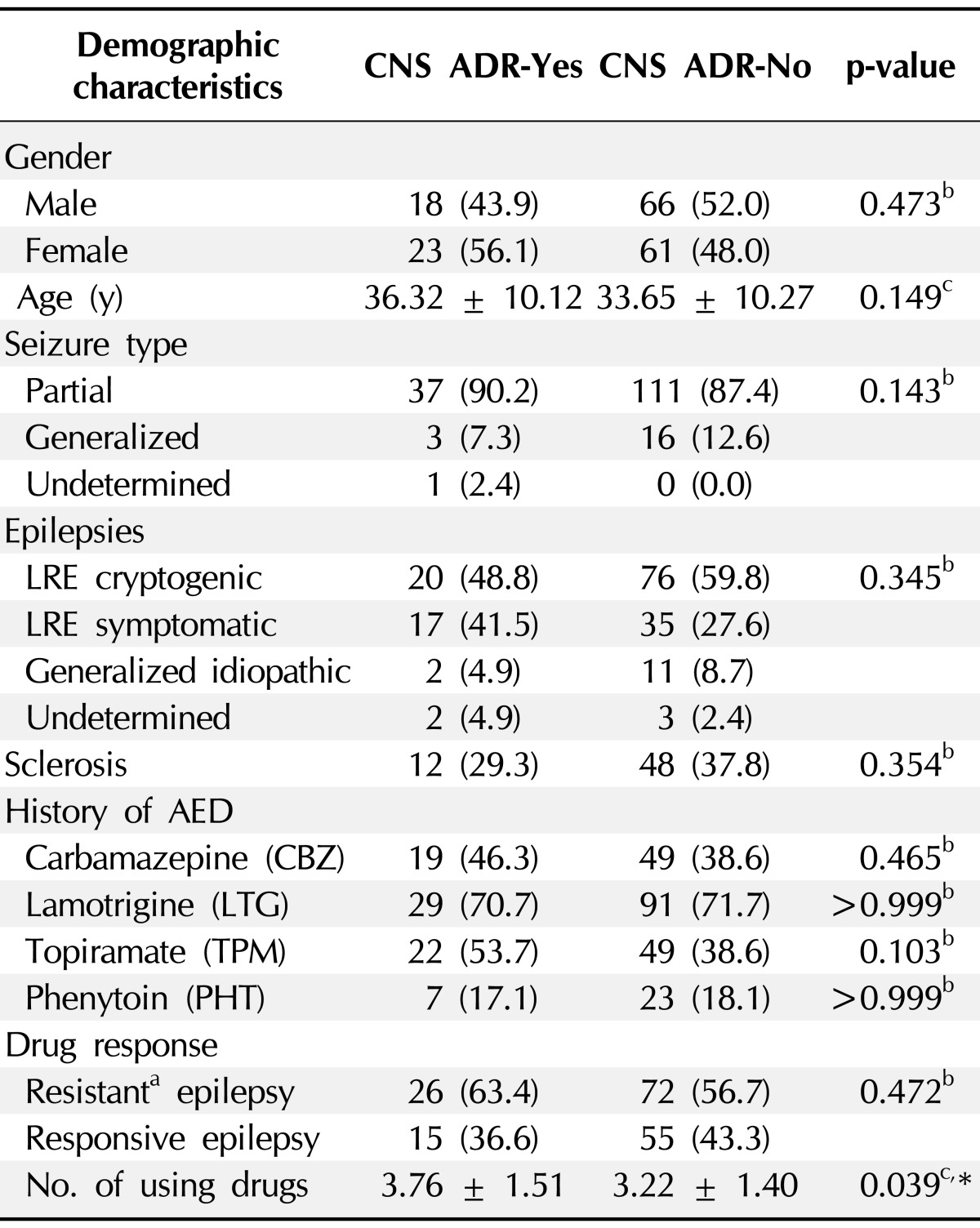

Demographic characteristics of the epileptic patients are presented in Table 1. DNA from control subjects (n = 110) was randomly selected from the DNA bank of the Korea Pharmacogenomics Research Network at Seoul National University. Blood samples were collected from each subject, and DNA was extracted using a QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of epilepsy patients treated with VPA

Values are presented as number (%).

VPA, valproic acid; CNS, central nervous system; ADR, adverse drug reaction; LRE, localization related epilepsy; AED, antiepileptic drug.

aDrug resistance was defined as the occurrence of at least four seizures during the previous year for patients who were being treated with more than three antiepileptic drugs at the maximally tolerable daily doses; bChi-square test was used; ct-test were used.

*p < 0.05 for comparison between CNS ADR-Yes and -No group.

Genetic analysis

Polymorphisms of the MDR1, MRP, and BCRP genes in the Korean population were discovered by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, two-dimensional gene scanning, and direct PCR using methods similar to those described in a previous paper [24]. Genotype screening of each locus in control and epileptic patients was performed by the SNaPshot or SNaPIT method (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), according to the protocols supplied by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis

Haploview software (version 3.2) was used to design MRP2 haplotype constructs and analyze major or minor haplotypes based on a standard expectation-maximization algorithm. Allele and genotype frequencies of transporter polymorphisms were assessed using chi-square tests (version 11.5 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Logistic regression

The strength of the association between dose-related CNS ADR patients and the presence of the G allele at the g.-1774 region was evaluated as the odds ratio (OR) obtained with logistic regression analysis (SPSS version 11.5). ORs were adjusted for gender, age, HS, use of AEDs (larmotrigene, CBZ, PHT, and topiramate), and the presence of the G allele at the g.-1774 promoter region.

Cell culture

SH-SY5Y (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), a human brain neuronal cell line originated from a neuroblastoma, was a gift from Dr. In Suk Kim, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. SH-SY5Y cells were maintained with Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 1% PS (100 units penicillin, 100 µg streptomycin, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, YSA) and were cultured under preconfluent monolayer conditions in 100-mm-diameter polyd-lysine-coated culture dishes at 37℃ with 5% humidified CO2.

Plasmid preparation of MRP2 promoter

A pGL3 basic vector containing the human MRP2 promoter region (about 2.3 kb, -2314 to +348 relative to the translation initiation site) was constructed by our group in a previous study from homozygotic persons with MRP2 haplotypes 1, 2, and 3 [24]. The g.-1774delG polymorphism is located in haplotype 1, and the g.-24C > T polymorphism is located in haplotype 3. The reporter vector of a minor haplotype variant containing only the g.-1549G > A variation was constructed using mutagenic primers, introducing a -24 T → C change to the plasmid of haplotype 3 containing both g.-1549G > A and g.-24C > T variations. Haplotype 2 includes no polymorphism (wild-type). In short, a total of five clones were prepared: pGL3 basic; haplotypes 1, 2, and 3; and g.-1549A alone.

Dual luciferase assay

The pGL3 basic vector containing WT MRP2 promoter variants was transfected into SH-SY5Y cells to measure the activity of the MRP2 promoter with and without VPA (P4543; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The day before transfection, 0.2 × 106 SH-SY5Y cells were seeded in a 12-well plate in order to reach 90-95% confluence at the time of transfection; 1.6 µg of pGL3-MRP2, including the variants and mock, was added to wells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Vector-containing Renilla luciferase was cotransfected in order to confirm the transfection efficiency of the pGL3-MRP2 vector. After a 3- to 5-h incubation, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen) and incubated at 37℃ with 5% humidified CO2 for 24 h. Reporter activity was measured using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). After removing the growth medium, cells were washed with PBS, and the plates were placed on a rocking platform shaker with 250 µL of 1 × passive lysis buffer per well for 15 min. Lysates were transferred to an e-tube, and luciferase binding was performed with 50 µL LARII and 10-50 µL cell lysate in a 96-well assay plate (Costar; Corning Incorp., Corning, NY, USA). After 10 s, light emission was measured using a luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Wildbad, Germany), and Stop & Glo was added to each well to stop firefly luciferase activity and evoke Renilla luciferase activity.

Results

SNP association with drug response or resistance

Drug resistance was defined as the occurrence of at least four seizures over the year before recruitment, with trials of more than three appropriate AED, at maximal tolerated doses, based on the occurrence of clinical side effects at supra-maximal doses [25]. The patients were classified as either responsive or resistant to drug therapy. We did not find any significant associations between the selected drug transporter SNPs and either group.

Clinical characteristics of epilepsy patients

A total of 41 (24%) epileptic patients had ADRs of the CNS, and 127 (76%) epileptic patients did not (non-ADR). The demographic characteristics are listed in Table 1. The gender frequency, drug response, and the average age of drug use between the two groups were similar. (p > 0.05) Subjects without ADRs used fewer drugs than those with ADRs (p = 0.039). The most frequent symptom out of 14 types of ADRs to VPA use was tremors (78.0%). Based on logistic regression, ADRs were more likely to occur in patients with g.-1774delG (presence of G allele), which had the highest OR (9.10) among the considered factors (p < 0.05).

Genetic polymorphisms of MRP2 in the Korean population

MRP polymorphisms covering all MRP2 exons, exonintron junctions, and the promoter region up to -2.3 Kb from the translation initiation site have been described in the Korean population [24]. We investigated 11 of the polymorphisms from previous studies in 110 healthy control people and 168 epileptic patients. We found four promoter, four exonic, and three intronic polymorphisms among them.

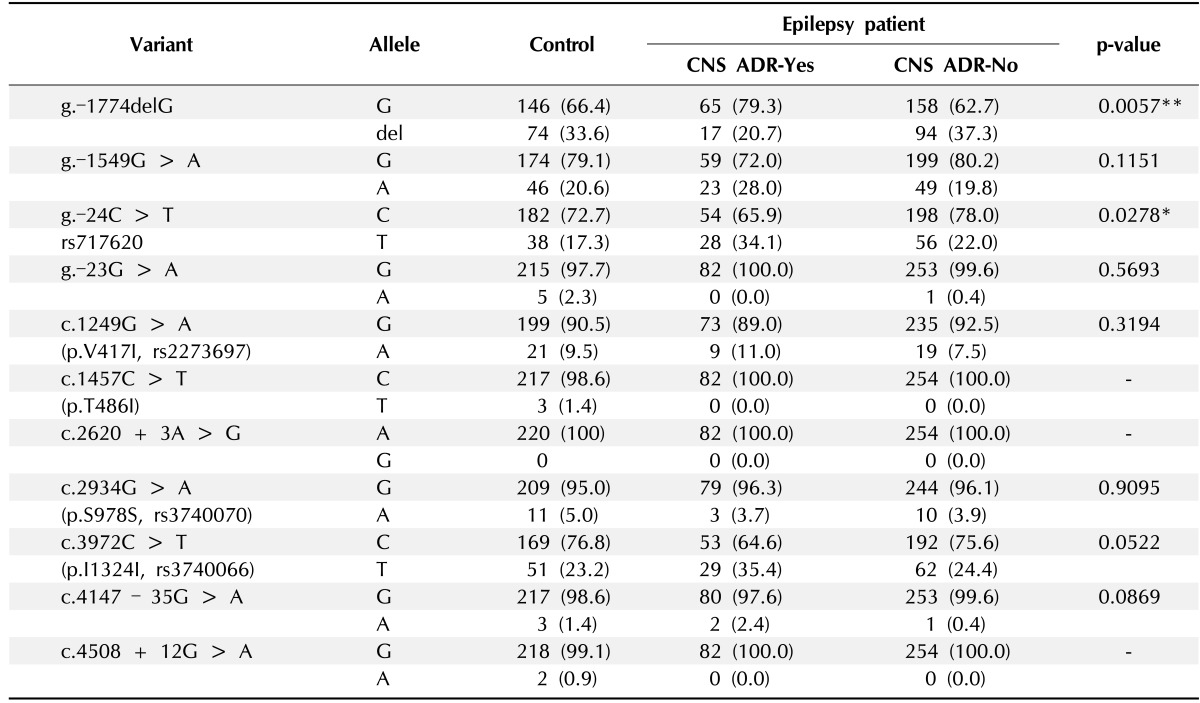

Relationship between genotypes of MRP2 and CNS ADRs to VPA

Allele frequencies of the MRP2 polymorphisms are shown in Table 2. Non-ADR patients were more likely to have the deletion allele instead of the G allele at g.-1774 when compared with patients with CNS ADRs (p = 0.0057; ADR, 20.7%; non-ADR, 37.3%). The frequency of the T allele at g.-24 was higher in patients with CNS ADRs than those without (p = 0.0274; ADR, 34.1%; non-ADR, 22.0%). The difference between the groups based on g.-24C > T frequencies was not significant after Bonferroni's correction, while the difference based on g.-1774delG frequencies remained significant.

Table 2.

Allele frequencies of the MRP2 polymorphisms

Values are presented as number (%).

CNS, central nervous system; ADR, adverse drug reaction.

p-values were obtained by comparisons between CNS ADR-Yes and -No groups using chi-square or Fisher's exact test (expected cell value <5). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

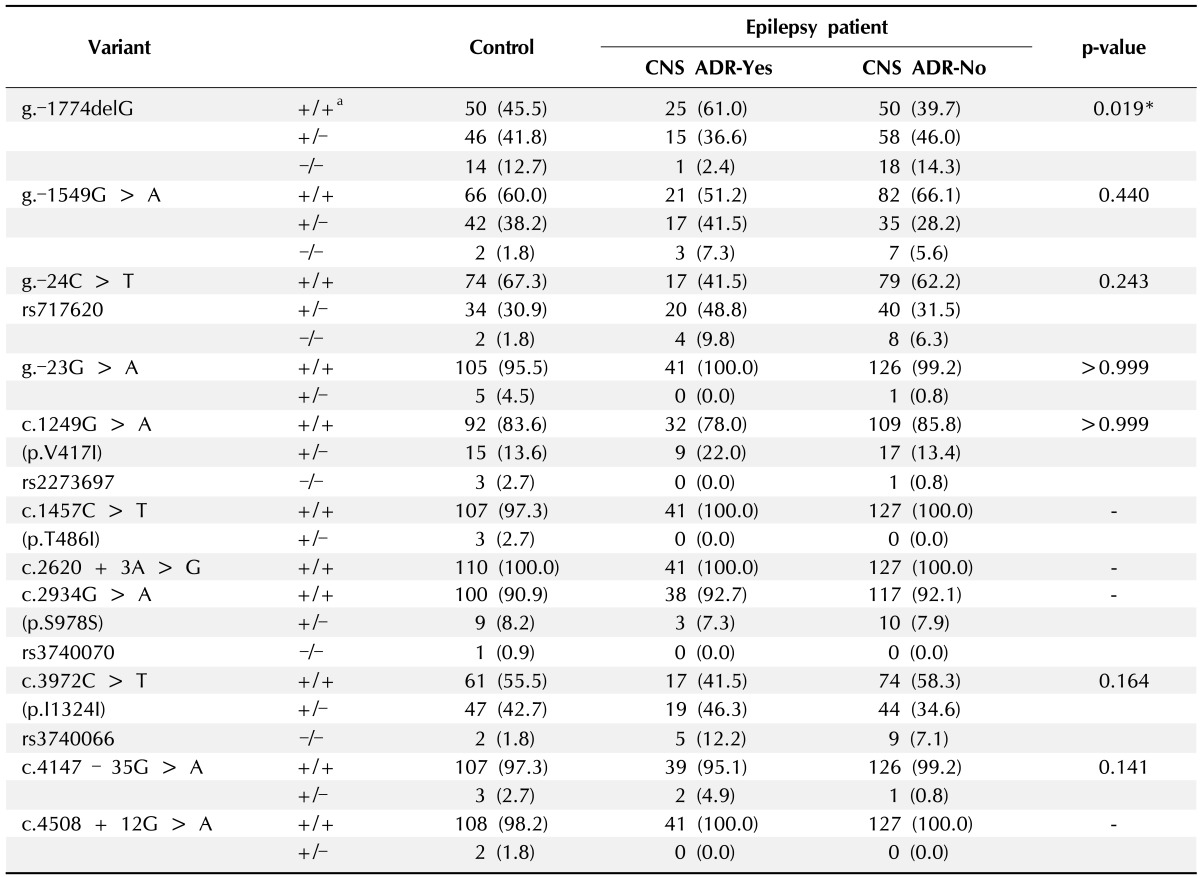

The genotype frequencies of each polymorphism are shown in Table 3. Genotype frequency distributions were consistent with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (each p > 0.5). The ADR group patients were more likely to have a GG genotype than a deldel genotype at g.-1774delG compared to the non-ADR group (p = 0.023, homo GG and deldel p = 0.0146). The TT and CT genotype frequencies at g.-24C > T were higher in patients with CNS ADRs than non-ADR patients (p = 0.035, hetero CT → TT p = 0.019).

Table 3.

Genotype distribution of MRP2 variants in control and epilepsy patients

Values are presented as number (%).

CNS, central nervous system; ADR, adverse drug reaction.

a+, major allele; -, minor allele.

p-values (+/+ vs. -/-) were obtained by comparisons between CNS ADR-Yes and -No groups using chi-square or Fisher's exact test (expected cell value < 5). *p < 0.05.

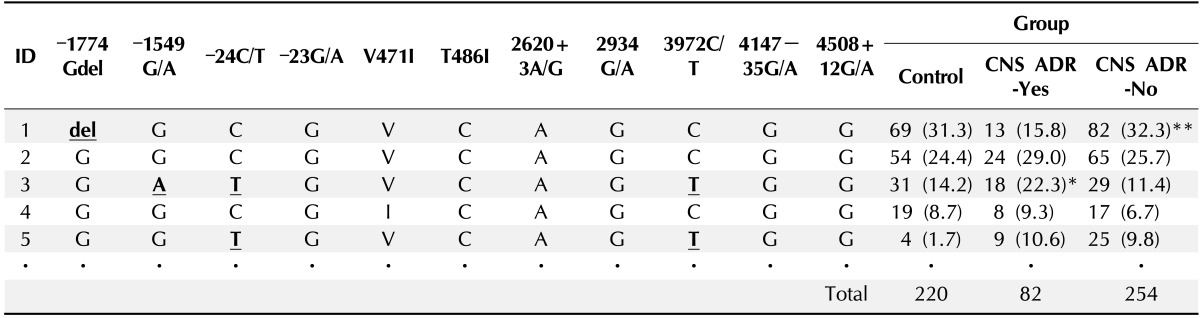

The frequencies of haplotypes present in at least 10% of the population are presented in Table 4. Haplotype frequencies of the MRP2 polymorphisms at all site. The frequency of haplotype 1 was significantly higher in patients without CNS ADRs (32.3%) than those with ADRs (15.8%) (p = 0.0039). The frequency of haplotype 3 was higher in patients with CNS ADRs than those without (p = 0.0139), but this difference was no longer significant after Bonferroni's correction was applied.

Table 4.

Frequency of MRP2 haplotypes in control and epilepsy patients

Values are presented as number (%).

Haplotypes were assembled using a software based on the Bayesian algorithm (Haploview, ref. No.). Major haplotypes showing over 5% frequency in control and epilepsy patients are presented in this table. Haplotype identification (ID) numbers were assigned according to the frequency of haploid genes analyzed in this study.

CNS, central nervous system; ADR, adverse drug reaction.

Differences between CNS ADR-Yes and -No groups were analyzed by chi-square analysis. *p = 0.0139, **p = 0.0039.

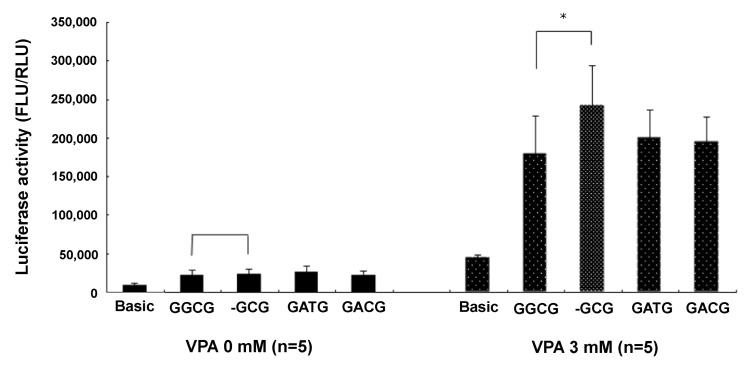

Measurement of MRP2 promoter activity

VPA stimulated MRP2 promoter activity about 10-fold. The epileptic patients with ADRs of the CNS had less haplotype 1 (containing g.-1774del) than the epileptic patients with no ADRs. By inference, the g.-1774G allele, a major allele of the MRP2 promoter sequence, was associated with ADRs of the CNS in patients treated with VPA. Epileptic patients with g.-1774del instead of g.-1774G were more likely to be resistant to VPA-related ADRs, probably because the g.-1774del allele produced higher MRP2 promoter activity than g.-1774G, leading to more MRP2 proteins in the brain tissue after VPA treatment. The presence of more MRP2 affected the distribution of AEDs (especially VPA) from the blood to the brain, resulting in the appearance of VPA-related ADRs in patients with g.-1774G rather than g.-1774del. Our luciferase assay data supported this hypothesis. There was no difference in luciferase activity between g.-1774del and the others (g.-1774G, g.-24C>T, g.-1549G > A) with non-VPA treatment. Luciferase activity was different, however, following 3 mM VPA treatment; g.-1774del promoter (haplotype 1) activity was 134% higher than g.-1774G promoter (haplotype 2) activity (n = 5; p < 0.05 by t-test). Further, the g.-1774del MRP2 promoter increased 1,014% with 3 mM VPA treatment compared to non-VPA treatment. However, the g.-1774G MRP2 promoter also increased 816% with 3 mM VPA treatment compared to non-VPA treatment. The change of g.-1774G → del increased the expression of MRP2 in neuronal SH-SY5Y cells treated with 3 mM VPA (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Luciferase activity of MRP2 promoter variants. Valproic acid (VPA) stimulated MRP2 promoter activity. The g.-1774del (-GCG) variant was more activated than g.-1774G (GGCG) in cells treated with 3 mM VPA. *p < 0.05.

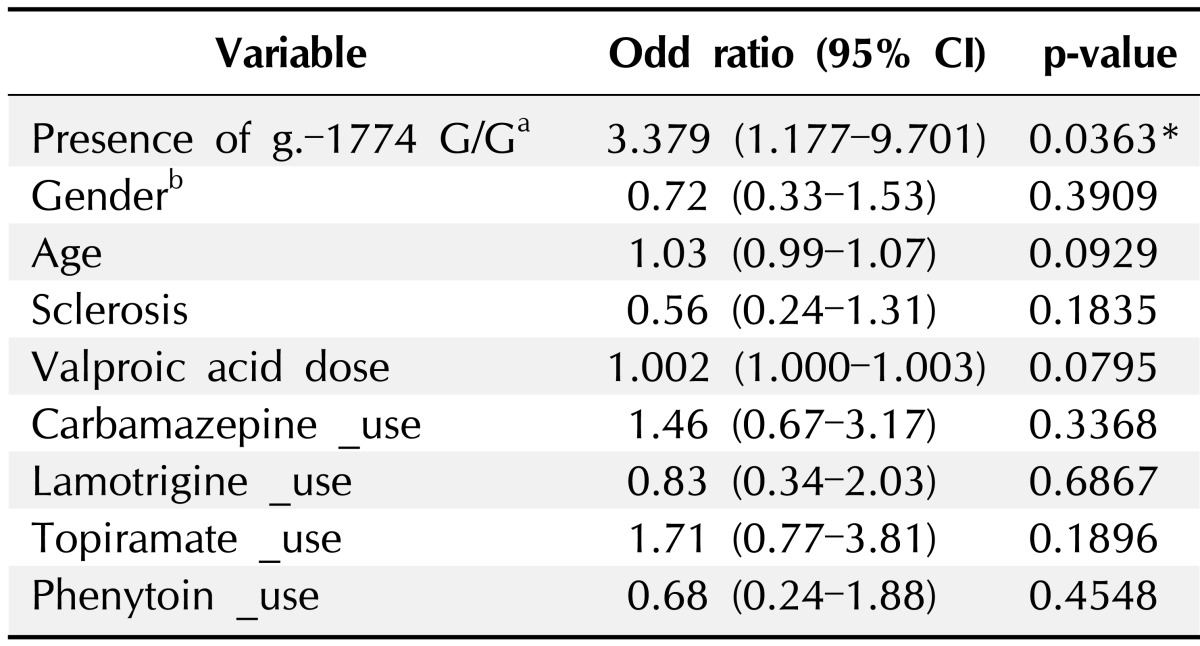

Factors influencing ADRs to VPA

Many factors, including gender; age; treatment with CBZ, lamotrigine, PHT, or topiramate; and HS, did not influence ADRs. The presence of the genotype G/G at the g.-1774 region of the MRP2 promoter influenced ADRs to VPA in epileptic patients. Logistic regression showed that the G/G correlated independently with ADRs to VPA (p < 0.05; OR, 9.102; 95% confidence interval, 1.111 to 73.378). The del/del allele was the reference category (Table 5). The G/G genotype at g.-1774 might influence lower expression of MRP2 than del/del in the brain, leading to ADRs.

Table 5.

Multiple logistic regression analysis for the determinants of CNS ADRs caused by VPA

CNS, central nervous system; ADR, adverse drug reaction; VPA, valproic acid; CI, confidence interval.

aReference category: Del/Del; bReference category: female, Logistic regression analysis was done using SPSS version 11.5.

*p < 0.05.

Discussion

The selective cellular barrier controlling drug delivery into the brain has been identified by the over-expression of MRP2 in capillary endothelia, astrocytes, and neuronal cells in previous studies [5, 26, 27]. In this study, we found that the g.-1774del genotype in the promoter region up-regulated the expression of MRP2. Patients with g.-1774del showed resistance to ADRs by increasing the expression of MRP2, followed by a decrease of drug concentration in the brain. Our data supported this hypothesis and verified an association between g.-1774delG and ADR.

The difference of luciferase activity between g.-1774G and g.-1774del in neuronal SH-SY5Y cells was not large. However, they showed extensive differences by statistical analysis (p < 0.05 by t-test). Because the expression level of MRP2 is lower in brain neuronal tissue than in hepatic tissue, even a little change is thought to be important. The luciferase assay of MRP2 promoter activity has not been conducted in brain capillary endothelial cells yet. In this cell line, SNP function is thought to be more effective, since MRP2 is more highly expressed in endothelial cells than in neuronal cells [28].

In reality, if MRP2 and other transporters are overexpressed in the brain, most patients should be not only non-ADR but also resistant to drug therapy. However, allele and genotype frequencies of g.-1774delG were not different between drug-resistant and drug-responsive patients (p > 0.05). The absence of a strict definition of drug-resistant epilepsy may have weakened the statistical analysis. The selected grouping was only a foundation for retrospective chart review. If the definition was stricter-for example, at least one seizure per year or non-seizure over the year-the different frequencies of g.-1774delG within each group would have been more significant. An accurate study design and definitions are a key part of effective pharmacogenomic studies [2]. Standards for association studies in pharmacogenomics have been presented in previous studies [2].

In spite of the retrospective study design, an association with g.-1774delG was noticeably significant. This SNP was reported previously in our group in relation to toxic hepatitis [24]. In that study, the g.-1774del genotype caused lower expression of MRP2 than g.-1774G in a human hepatocyte-originated cell line (HepG2). This finding is contrary to the results of the present study. There are different known transcription factors in hepatocytes and neuronal and endothelial cells. The promoter activity in the cells transfected with a g.-1774G (haplotype 2) clone was about 100 times stronger than those transfected with the control vector in hepatic cells. A strong transcriptional activator is present in hepatocytes. However, the difference in promoter activity between g.-1774G and mock control was lower in neuronal SH-SY5Y cell lines. Neuronal transcription factors are expected to be weaker than those in hepatocytes. The binding sequence is "AAAAACAACAAGATAA" (the underlined C is the anti-sense sequence at g.-1774G). Transcription factors that are known to bind this sequence are GATA-1, Evi-1, FOXO, HNF3, and more (Genomatix software GmbH). Each tissue-specific transcription factor binds this sequence and induces different levels of MRP2 expression. For example, HNF3, a common activator in hepatocytes, was thought to activate MRP2 expression through binding with g.-1774G rather than g.-1774del. Consequently, the expression of MRP2 of g.-1774del would be lower than g.-1774G. In contrast, if neuronal cell transcriptional activators were more likely to bind g.-1774del over g.-1774G, neuronal expression of MRP2 of g.-1774del would be higher than g.-1774G. The factors that bind to this region have yet to be determined. Previous studies have referred to the different binding factors of this region in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells without specific identification.

In the present study, a luciferase assay demonstrated that VPA stimulated the activity of the MRP2 promoter in SH-SY5Y cells. VPA is a well-known histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor that induces apoptosis in cancer cells [29, 30]. In normal cells, however, VPA activates chromosomal transcriptional ability by inhibiting HDAC. Chromosomal DNA forms a compact nucleosome with histone proteins and needs to be unpacked in order to start transcription. HDAC removes the acetyl group in acetyl-lysine residues and biologically inhibits the activity of transcription [31]. In neuronal SH-SY5Y cells, VPA could activate the MRP2 promoter by inhibiting HDAC. MRP2 has farnesoid X receptor, retinoid X receptor (RXR), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor/RXR binding regions. VPA interacts with these proteins and regulates the expression level of MRP2 protein [32, 33].

P-gp polymorphisms have repeatedly been associated with drug response in epilepsy [25, 34-37]. Up to now, however, the only functional studies of MRP2 have been conducted in a knockout animal model [38]. This report is the first investigation to show an association between MRP2 polymorphisms and ADRs in epilepsy. These results may be useful in tailoring AED medication. The G allele of the MRP2 promoter was associated with ADRs to VPA in Korean epileptic patients. The del allele of MRP2 protected the brain against adverse effects of VPA by over-expressing MRP2 in brain neuronal cells. These data will help design therapy to minimize ADRs in epileptic patients and aid in the development of new AEDs. However, further independent replication studies are needed to unequivocally confirm the association.

References

- 1.Duncan JS, Sander JW, Sisodiya SM, Walker MC. Adult epilepsy. Lancet. 2006;367:1087–1100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Depondt C, Shorvon SD. Genetic association studies in epilepsy pharmacogenomics: lessons learnt and potential applications. Pharmacogenomics. 2006;7:731–745. doi: 10.2217/14622416.7.5.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maines LW, Antonetti DA, Wolpert EB, Smith CD. Evaluation of the role of P-glycoprotein in the uptake of paroxetine, clozapine, phenytoin and carbamazapine by bovine retinal endothelial cells. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:610–617. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbott NJ, Romero IA. Transporting therapeutics across the blood-brain barrier. Mol Med Today. 1996;2:106–113. doi: 10.1016/1357-4310(96)88720-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dombrowski SM, Desai SY, Marroni M, Cucullo L, Goodrich K, Bingaman W, et al. Overexpression of multiple drug resistance genes in endothelial cells from patients with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42:1501–1506. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.12301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clatterbuck RE, Eberhart CG, Crain BJ, Rigamonti D. Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical evidence that an incompetent blood-brain barrier is related to the pathophysiology of cavernous malformations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:188–192. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans WE, McLeod HL. Pharmacogenomics: drug disposition, drug targets, and side effects. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:538–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Han H, Elmquist WF, Miller DW. Expression of various multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) homologues in brain microvessel endothelial cells. Brain Res. 2000;876:148–153. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02628-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potschka H, Fedrowitz M, Löscher W. P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance-associated protein are involved in the regulation of extracellular levels of the major antiepileptic drug carbamazepine in the brain. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3557–3560. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200111160-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aronica E, Gorter JA, Redeker S, van Vliet EA, Ramkema M, Scheffer GL, et al. Localization of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) in microvessel endothelium of human control and epileptic brain. Epilepsia. 2005;46:849–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.66604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Vliet EA, Redeker S, Aronica E, Edelbroek PM, Gorter JA. Expression of multidrug transporters MRP1, MRP2, and BCRP shortly after status epilepticus, during the latent period, and in chronic epileptic rats. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1569–1580. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aronica E, Gorter JA, Ramkema M, Redeker S, Ozbas-Gerceker F, van Vliet EA, et al. Expression and cellular distribution of multidrug resistance-related proteins in the hippocampus of patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2004;45:441–451. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.57703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Löscher W, Potschka H. Role of drug efflux transporters in the brain for drug disposition and treatment of brain diseases. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76:22–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potschka H, Fedrowitz M, Löscher W. Multidrug resistance protein MRP2 contributes to blood-brain barrier function and restricts antiepileptic drug activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:124–131. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerveny L, Pavek P, Malakova J, Staud F, Fendrich Z. Lack of interactions between breast cancer resistance protein (bcrp/abcg2) and selected antiepileptic agents. Epilepsia. 2006;47:461–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potschka H, Fedrowitz M, Löscher W. Brain access and anticonvulsant efficacy of carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and felbamate in ABCC2/MRP2-deficient TR- rats. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1479–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.22603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huai-Yun H, Secrest DT, Mark KS, Carney D, Brandquist C, Elmquist WF, et al. Expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) in brain microvessel endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;243:816–820. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adkison KD, Artru AA, Powers KM, Shen DD. Contribution of probenecid-sensitive anion transport processes at the brain capillary endothelium and choroid plexus to the efficient efflux of valproic acid from the central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;268:797–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright AW, Dickinson RG. Abolition of valproate-derived choleresis in the MRP2 transporter-deficient rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:584–588. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niemi M, Arnold KA, Backman JT, Pasanen MK, Gödtel-Armbrust U, Wojnowski L, et al. Association of genetic polymorphism in ABCC2 with hepatic multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 expression and pravastatin pharmacokinetics. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006;16:801–808. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000230422.50962.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirouchi M, Suzuki H, Itoda M, Ozawa S, Sawada J, Ieiri I, et al. Characterization of the cellular localization, expression level, and function of SNP variants of MRP2/ABCC2. Pharm Res. 2004;21:742–748. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000026422.06207.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wada M, Toh S, Taniguchi K, Nakamura T, Uchiumi T, Kohno K, et al. Mutations in the canilicular multispecific organic anion transporter (cMOAT) gene, a novel ABC transporter, in patients with hyperbilirubinemia II/Dubin-Johnson syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:203–207. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer zu Schwabedissen HE, Jedlitschky G, Gratz M, Haenisch S, Linnemann K, Fusch C, et al. Variable expression of MRP2 (ABCC2) in human placenta: influence of gestational age and cellular differentiation. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:896–904. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.003335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi JH, Ahn BM, Yi J, Lee JH, Nam SW, Chon CY, et al. MRP2 haplotypes confer differential susceptibility to toxic liver injury. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:403–415. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000236337.41799.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siddiqui A, Kerb R, Weale ME, Brinkmann U, Smith A, Goldstein DB, et al. Association of multidrug resistance in epilepsy with a polymorphism in the drug-transporter gene ABCB1. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1442–1448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cooray HC, Blackmore CG, Maskell L, Barrand MA. Localisation of breast cancer resistance protein in microvessel endothelium of human brain. Neuroreport. 2002;13:2059–2063. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200211150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Löscher W, Potschka H. Role of multidrug transporters in pharmacoresistance to antiepileptic drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:7–14. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffmann K, Gastens AM, Volk HA, Löscher W. Expression of the multidrug transporter MRP2 in the blood-brain barrier after pilocarpine-induced seizures in rats. Epilepsy Res. 2006;69:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang X, Guo B. Adenomatous polyposis coli determines sensitivity to histone deacetylase inhibitor-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9245–9251. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takai N, Desmond JC, Kumagai T, Gui D, Said JW, Whittaker S, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors have a profound antigrowth activity in endometrial cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1141–1149. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin HJ, Baek KH, Jeon AH, Kim SJ, Jang KL, Sung YC, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity increases chromosomal instability by the aberrant regulation of mitotic checkpoint activation. Oncogene. 2003;22:3853–3858. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catania VA, Sánchez Pozzi EJ, Luquita MG, Ruiz ML, Villanueva SS, Jones B, et al. Co-regulation of expression of phase II metabolizing enzymes and multidrug resistance-associated protein 2. Ann Hepatol. 2004;3:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai G, Chou N, He L, Gyamfi MA, Mendy AJ, Slitt AL, et al. Retinoid X receptor alpha Regulates the expression of glutathione s-transferase genes and modulates acetaminophenglutathione conjugation in mouse liver. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1590–1596. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.013680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seo T, Ishitsu T, Ueda N, Nakada N, Yurube K, Ueda K, et al. ABCB1 polymorphisms influence the response to antiepileptic drugs in Japanese epilepsy patients. Pharmacogenomics. 2006;7:551–561. doi: 10.2217/14622416.7.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zimprich F, Sunder-Plassmann R, Stogmann E, Gleiss A, Dal-Bianco A, Zimprich A, et al. Association of an ABCB1 gene haplotype with pharmacoresistance in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2004;63:1087–1089. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000141021.42763.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan NC, Heron SE, Scheffer IE, Pelekanos JT, McMahon JM, Vears DF, et al. Failure to confirm association of a polymorphism in ABCB1 with multidrug-resistant epilepsy. Neurology. 2004;63:1090–1092. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000137051.33486.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimprich F, Sunder-Plassmann R, Stogmann E, Gleiss A, Dal-Bianco A, Zimprich A, et al. Association of ABCB1 gene haplotypes with pharmacoresistance in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2004;63:1087–1089. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000141021.42763.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffmann K, Gastens AM, Volk HA, Löscher W. Expression of the multidrug transporter MRP2 in the blood-brain barrier after pilocarpine-induced seizures in rats. Epilepsy Res. 2006;69:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]