Abstract

The molecular vibration-activity relationship in the receptor-ligand interaction of adenosine receptors was investigated by structure similarity, molecular vibration, and hierarchical clustering in a dataset of 46 ligands of adenosine receptors. The resulting dendrogram was compared with those of another kind of fingerprint or descriptor. The dendrogram result produced by corralled intensity of molecular vibrational frequency outperformed four other analyses in the current study of adenosine receptor agonism and antagonism. The tree that was produced by clustering analysis of molecular vibration patterns showed its potential for the functional classification of adenosine receptor ligands.

Keywords: corralled intensity of molecular vibrational frequency, G-protein-coupled receptors, molecular descriptor, molecular vibration-activity relationship, purinergic P1 receptors

Introduction

Membrane proteins play crucial roles in organismal transduction of information. Molecular recognition in biological membrane systems is the initial process triggering external factors to be passed into the inner part of a cell. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which consist of 7 transmembrane segments, play pivotal roles for signal transduction in higher eukaryotes and organize the largest families of proteins in the human genome [1]. The fact that drugs targeting GPCRs constitute over one-third of pharmaceuticals shows the importance of GPCRs as drug targets [2].

Adenosine receptors (AdoRs) belong to a family of rhodopsin-like class A GPCRs, which constitute the largest portion of GPCRs in humans, including olfactory receptors, and there are four known subtypes of AdoRs-namely, AdoR1, AdoRA2A, AdoRA2B, and AdoR3 [3, 4]. Although these AdoR subtypes have distinct amino acid sequences and tissue-specific distribution, their endogenous agonist and ligand-binding pockets are highly conserved.

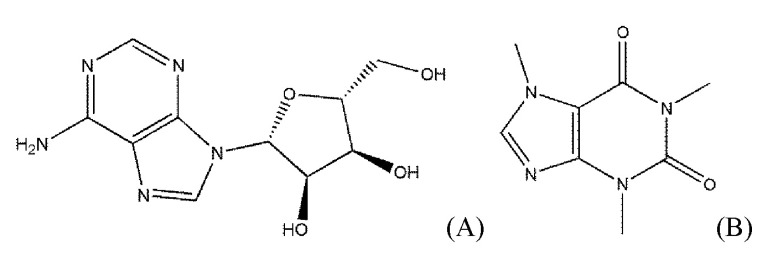

The biogenic nucleoside adenosine (Fig. 1) exerts its effects by interacting with AdoRs that are involved in various diseases, such as cardiac ischemia, arrhythmia, neurodegeneration, diabetes, glaucoma, and inflammation [5]. The physiological effects of AdoRs can be used for diagnoses and planning of the surgical strategies, such as in coronary artery diseases [6].

Fig. 1.

The chemical structures of adenosine and caffeine as an agonist and an antagonist of adenosine receptors, respectively. (A) Adenosine, an endogenous agonist of adenosine receptors. (B) Caffeine, a typical antagonist of adenosine receptors.

Olfaction, the sense of smell, is also mediated by class A GPCRs-namely, olfactory receptors. The fundamental mechanism of olfaction is now under some controversy [7-9]. Various attempts were introduced to describe the molecular mechanism of receptor-ligand recognition in olfaction, such as the binding theory and vibration theory [10-12]. The former, where the specificity of ligand is explained by molecular shape, has been developed into a concept of a pharmacophore and is generally accepted by researchers. Nevertheless, this is not sufficient to give the account of ligand variety and agonism complexity of GPCRs.

In recent decades, there have been many efforts to find an efficient way to seek or make appropriate ligands working on the target receptors through a chemogenomic approach. Application of molecular descriptors can make an efficient way to discriminate ligand binding modes in receptor-ligand relationships in such cases as in silico chemogenomic screening [13]. Molecular descriptors encoding information about the molecular structure can be classified by the dimensionality of their molecular representation, and they are almost on the structural, topological, and geometrical bases [14]. They are also including information on dipole moment, electric polarizability, and electrostatic potential in their data types.

Lately, a computational approach was carried out to search for a molecular vibration-activity relationship in the agonism of histamine receptors, and the author suggested that the molecular vibrational frequency pattern may play a role as a possible molecular descriptor for histamine receptor ligands [15]. The EigenVAlue (EVA) descriptor is also based on infrared range molecular vibrations among the various molecular descriptors and is a unique one, based on eigenvalues corresponding to individual calculated normal modes among various molecular descriptors [16, 17].

In the present paper, we tested the potential of the corralled intensity of molecular vibrational frequency (CIMVF) [15] as a molecular descriptor, compared to the EVA descriptor and other descriptors for the classification of AdoR ligands.

Methods

Dataset

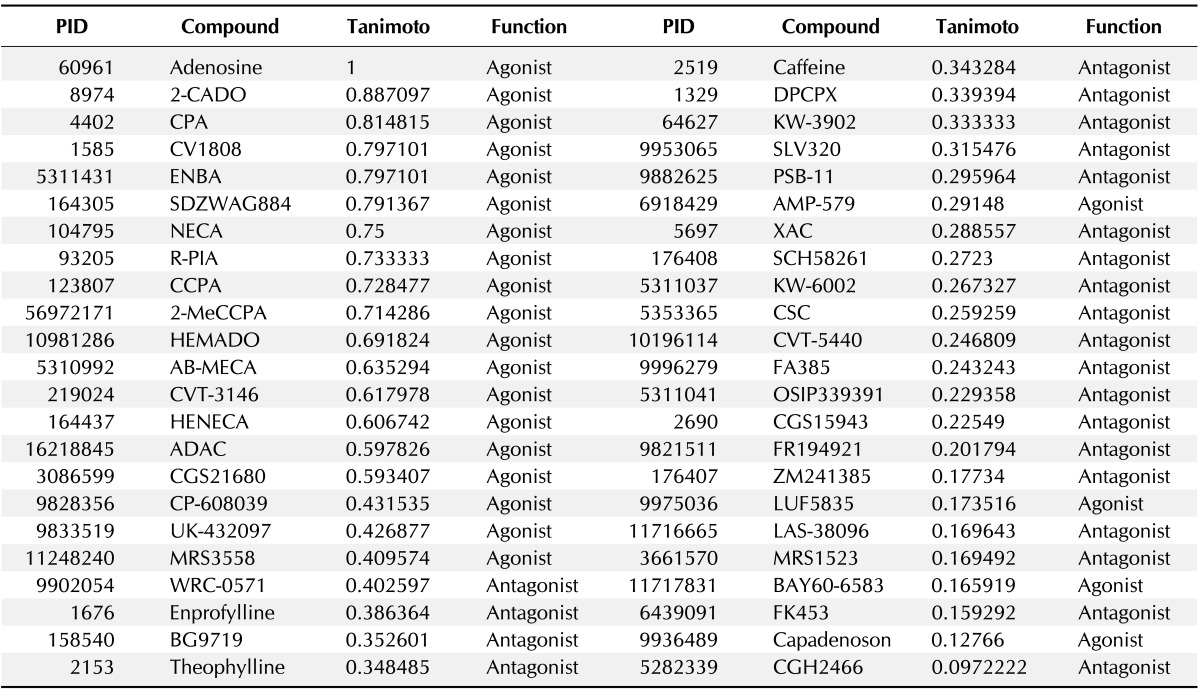

All 46 ligand molecules in the dataset, comprising 23 AdoR agonists and 23 antagonists, are shown in Table 1, with the Tanimoto distance of each ligand from adenosine.

Table 1.

Dataset of adenosine receptor ligands used in the present study and their molecular similarity in the Tanimoto coefficient to adenosine

PID, PubChem ID.

The Tanimoto coefficient is a widely used measure of molecular structural similarity. The coefficient is defined as Tc = Nab/(Na + Nb - Nab), with Nab being the number of common bits, Na the unique bits in molecule a, and Nb the unique bits in molecule b, using a molecular fingerprint [18]. In this study, the molecular similarity to adenosine was calculated as the Tanimoto coefficient using the 38-bit set. The simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) and 3-dimensional structure data format (SDF) files of the dataset were downloaded from the PubChem Compound Database in National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and used in further analyses.

Molecular descriptors

Molecular fingerprints: MACCS keys, PubChem, and Klekota-Roth fingerprint

Molecular fingerprints are binary bit string representations that capture diverse aspects of molecular structure and properties and are popular tools for virtual screening [19]. In this study, three fingerprints-MACCS keys [20], PubChem fingerprint [21], and Klekota-Roth fingerprint [22]-were tested to be compared with the Tanimoto coefficient and other descriptors. The descriptor numbers of the MACCS, PubChem, and Klekota-Roth fingerprints are 320, 881, and 4860, respectively. The MACCS keys of each ligand were generated by a MACCS key generator, and the other two fingerprints of the ligands were calculated by PaDEL-Descriptor [23].

EVA descriptor

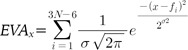

An ideal molecular descriptor should encode all the features of a molecule in numerical form. EVA, based on the normal coordinate eigenvalues, is derived from calculated infrared range vibrational frequencies and consequently has the characteristic feature of molecular-specific vibration. The resulting vibrational frequencies were then convolved using a sum of Gaussian functions to generate a pseudospectrum of 3N-6 overlapping kernels:

|

, where N is the number of atoms, σ is a fixed standard deviation of the Gaussian function, and fi is the i-th frequency of the molecule. We fixed the value of σ to 5 cm-1 in this study.

CIMVF descriptor

For a simplified comparison of the molecular vibration patterns, the calculated molecular vibrations of a ligand were sorted in increasing order and taken into each corral with a fixed step (e.g., 5 cm-1) size. The intensities of each molecular vibrational frequency in the same corral were summed up as the representative of the corral. As a molecular descriptor of a ligand, the intensity of each corral is displayed in a 1-dimensional vector containing 800 elements from the vibrational frequency range of 0-4,000 cm-1. The calculations of CIMVF were performed by in-house scripts written in Python.

EVA and CIMVF descriptors were produced from PubChem SDF data of ligands through geometry optimization and calculations of molecular vibrations with the GAMESS program package [24]. The similarity matrices obtained from these five cases of molecular representations were subjected to hierarchical clustering using complete linkage method.

Calculation of molecular vibration

Since the EVA and CIMVF descriptors require geometry optimization of a given molecule, each provided theoretical 3-D conformer SDF underwent single low-energy conformation using the GAMESS program package [24]. Restricted Hartree-Fock calculations using the BLYP DFT method with the 6-31G basis set were performed to optimize the geometries of the molecules. Each result was taken as the representative conformation of the molecule, although the calculation of molecular vibrational frequency has some dependence on conformation. The results of geometry optimization were subjected to the calculation step for the molecular vibrational frequency with RUNTYP of HESSIAN in the GAMESS program.

Hierarchical clustering of molecular descriptors and dendrogram structure comparison

To test the availability of CIMVF as a molecular descriptor for the classification of AdoR ligands, a kind of molecular calculation using agglomerative hierarchical clustering was adopted in this work.

Each fingerprint or descriptor of ligands was gathered into a matrix of cognate fingerprint or descriptor. Finally, the similarity matrix, comprising descriptors of 46 ligands of AdoRs, was then subjected to hierarchical clustering in the agglomerative manner. In this study, each similarity matrix was finally clustered to make a dendrogram of 46 vertices. To compare the structures of the resulting dendrogram, we used a program for pairwise comparison of phylogenies, which shows the topological difference between two dendrograms [25]. The multiple comparison of the 5 dendrograms was also carried out using a meta-tree-generating program for comparing multiple alternative dendrograms [26].

Results and Discussion

As shown in Fig. 1, adenosine and caffeine, a typical agonist and antagonist of AdoRs, respectively, share the structure of purine. However, the Tanimoto coefficient between the two ligands is not high. The Tanimoto coefficient of some agonists to adenosine was lower than 0.3, though they did not take a large share. Moreover, the lowest Tanimoto coefficient of the agonists was 0.12766 (capadenoson) and is a lower value as an antagonist.

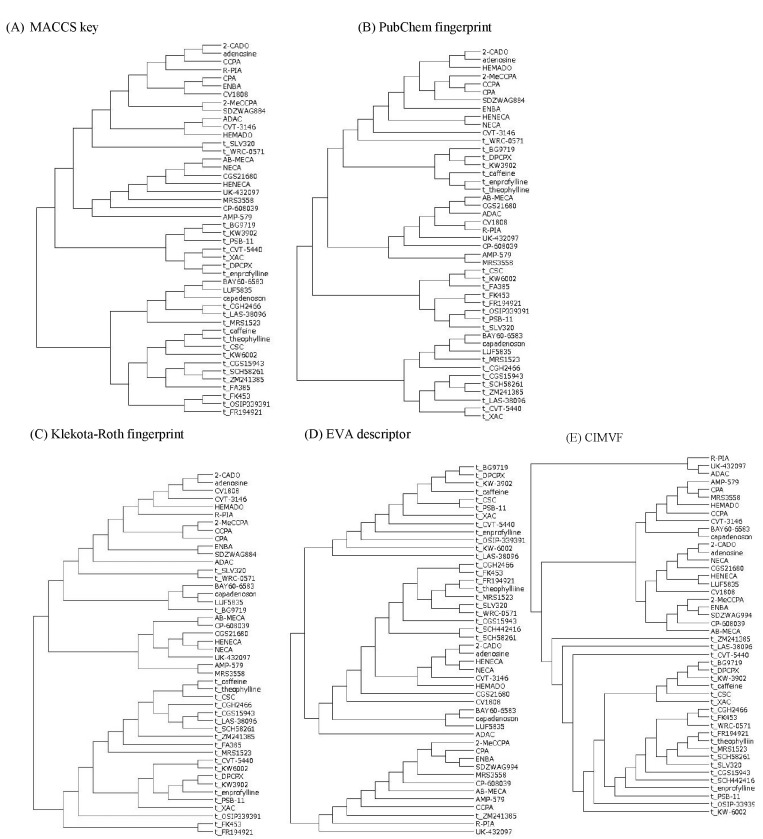

The results of hierarchical clustering of the similarity matrices from the MACCS keys, PubChem, and Klekota-Roth fingerprints; EVA; and CIMVF are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Dendrograms of clustering using fingerprints, EigenVAlue (EVA), and corralled intensity of molecular vibrational frequency (CIMVF) by complete linkage method. Antagonists were tagged with "t_" to their chemical names as a prefix. (A) MACCS keys. Agonists with low Tanimoto coefficient to adenosine were clustered to a subtree of antagonists. (B) PubChem fingerprint. The clustering result of the PubChem fingerprint was similar to that of MACCS clustering. (C) Klekota-Roth fingerprint. Some antagonists were located in a subtree of agonists. (D) EVA. About half of the antagonists were located in the cluster of agonists. An antagonist, ZM241385, was clustered in the agonist subtree. (E) CIMVF. All agonists and antagonists were categorized to each cluster.

The dendrograms obtained from MACCS keys and PubChem fingerprint were shown to be similar to the Tanimoto coefficient pattern. The result of the Klekota-Roth fingerprint analysis showed a somewhat different pattern to the fingerprint-based one, as only two antagonists were located in the cluster of agonists. However, the three fingerprint-based results did not match the known facts of AdoR agonism.

In the case of EVA, Takane and Mitchell [27] reported a structure-odor relationship using the EVA descriptor and hierarchical clustering. The authors reported that the dendrograms that were produced by the EVA method outperformed those from UNITY 2D in a classification of odorant molecules. However, the EVA analysis in the current study was positive but not perfect for the molecular property-activity relationship in AdoR agonism. The larger σ got, the more the clusters in the dendrogram got entangled (data not shown). It might come from the Gaussian function that smeared out the vibrational frequencies, such that vibrations of similar frequency overlapped together. The dendrogram obtained from the EVA descriptor showed an eligible tree for the agonism of AdoRs on the whole (Fig. 2D). One exception in which an antagonist (ZM241385) was clustered in a subtree of agonists might have resulted from smoothing by the Gaussian convolution of molecular vibration data.

All antagonists were clustered into a subtree in the dendrogram obtained from CIMVF analysis, as shown in Fig. 2E. We can tell the regional difference between agonists and antagonists in the dendrogram and also find that the information from the CIMVF analysis can play a role in the discrimination of agonists from antagonists in AdoR agonism. The discreteness of CIMVF data seems to facilitate the performance of the binary classification of AdoR ligands.

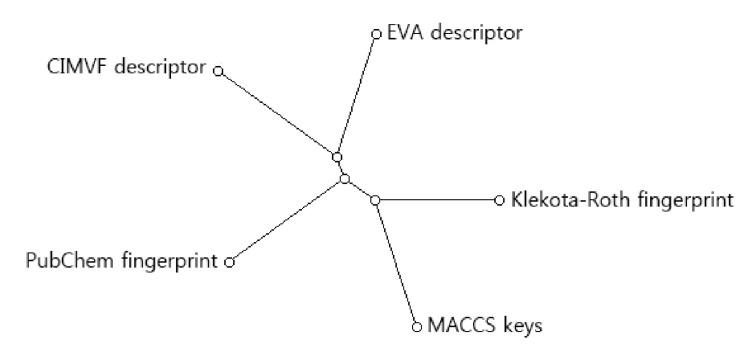

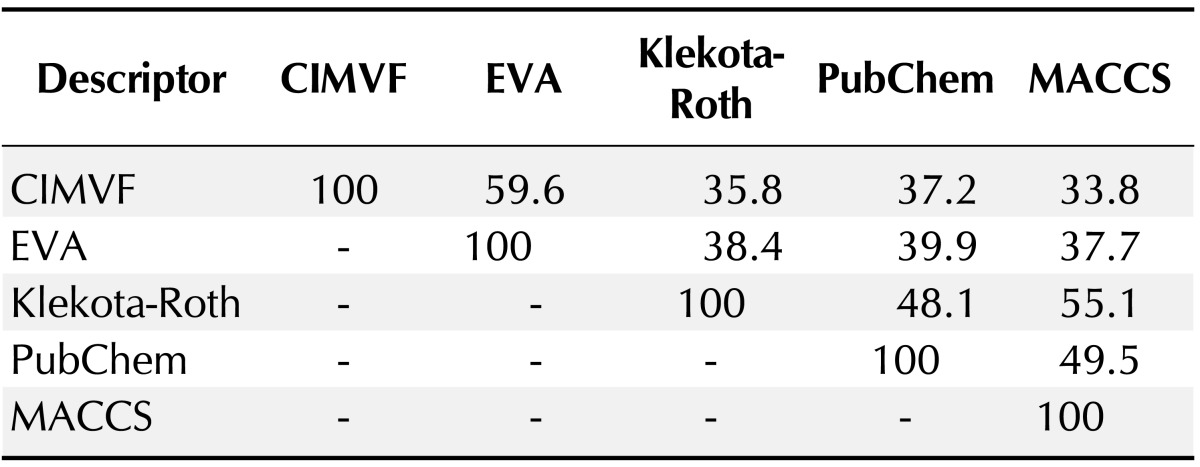

To find the topological difference between dendrograms, similarity scores between every two dendrograms were shown in Table 2. The similarity between two dendrograms was represented as a percentage. For example, the score of topological similarity between the two dendrograms of CIMVF and EVA analyses is 59.6%. The value has the highest similarity among all comparisons. A distance meta-tree build from five dendrograms of 46 AdoR ligands was illustrated in Fig. 3. As shown in the tree, the resulting dendrogram produced from the CIMVF data analysis has the nearest position to that produced from the EVA data analysis and is located the farthest from the dendrogram produced from the analysis of MACCS keys.

Table 2.

Topological difference between dendrograms in Fig. 2

CIMVF, corralled intensity of molecular vibrational frequency; EVA, EigenVAlue.

Fig. 3.

Meta-tree build from multiple comparison of 5 dendrograms. CIMVF, corralled intensity of molecular vibrational frequency; EVA, EigenVAlue.

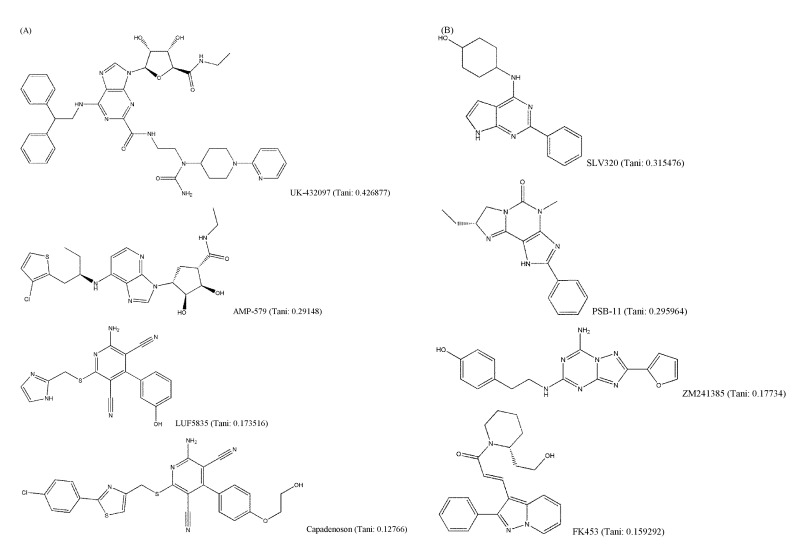

It is generally known that structurally similar molecules have similar properties or functions; however, a small change in molecular structure can fairly affect its vibrational frequencies. The structural variety of AdoR ligands was shown in Fig. 4. The Tanimoto coefficients of LUF5835, BAY60-6583, and capadenoson to adenosine were smaller than 0.18, and the ligands share a hydroxyphenyl pyridine dicarbonitrile backbone (Fig. 4A). They seem to be dissimilar to other agonists that share the structure of purine. Several antagonists (Fig. 4B) do not have a similar structure to caffeine; however, they act as antagonists of AdoRs.

Fig. 4.

Structural variety of adenosine receptors (AdoR) ligands (Tani: Tanimoto coefficient to adenosine). (A) AdoR agonists. (B) AdoR antagonists.

As mentioned above, the current experiment does provide circumstantial evidence for the molecular vibrational information to AdoR agonism, at least. With a more concentrated study on the relationship between the molecular vibrational frequency and pharmacological function of a ligand, the vibrational spectrum of a ligand molecule may explicitly propose a novel path to the field of receptor-ligand interaction mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to Prof. C. H. Choi for the use of his cluster computer and his valuable advice. This work was supported by the 2011 Inje University research grant.

References

- 1.Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rask-Andersen M, Almén MS, Schiöth HB. Trends in the exploitation of novel drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:579–590. doi: 10.1038/nrd3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Linden J, Müller CE. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors: an update. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:1–34. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ko SM, Choi JW, Hwang HK, Song MG, Shin JK, Chee HK. Diagnostic performance of combined noninvasive anatomic and functional assessment with dual-source CT and adenosine-induced stress dual-energy CT for detection of significant coronary stenosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:512–520. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haffenden LJ, Yaylayan VA, Fortin J. Investigation of vibrational theory of olfaction with variously labelled benzaldehydes. Food Chem. 2001;73:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keller A, Vosshall LB. A psychophysical test of the vibration theory of olfaction. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:337–338. doi: 10.1038/nn1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franco MI, Turin L, Mershin A, Skoulakis EM. Molecular vibration-sensing component in Drosophila melanogaster olfaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3797–3802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012293108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malcolm Dyson G. The scientific basis of odour. J Soc Chem Ind. 1938;57:647–651. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright RH. Odour and chemical constitution. Nature. 1954;173:831. doi: 10.1038/173831a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright RH. Odor and molecular vibration: neural coding of olfactory information. J Theor Biol. 1977;64:473–502. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(77)90283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris CJ, Stevens AP. Chemogenomics: structuring the drug discovery process to gene families. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:880–888. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scior T, Bender A, Tresadern G, Medina-Franco JL, Martínez-Mayorga K, Langer T, et al. Recognizing pitfalls in virtual screening: a critical review. J Chem Inf Model. 2012;52:867–881. doi: 10.1021/ci200528d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh SJ. Characteristics in molecular vibrational frequency patterns between agonists and antagonists of histamine receptors. Genomics Inform. 2012;10:128–132. doi: 10.5808/GI.2012.10.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson AM, Heritage T, Jonathon P, Pack SE, Phillips L, Rogan J, et al. EVA: a new theoretically based molecular descriptor for use in QSAR/QSPR analysis. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 1997;11:143–152. doi: 10.1023/a:1008026308790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner DB, Willett P, Ferguson AM, Heritage T. Evaluation of a novel infrared range vibration-based descriptor (EVA) for QSAR studies. 1. General application. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 1997;11:409–422. doi: 10.1023/a:1007988708826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godden JW, Xue L, Bajorath J. Combinatorial preferences affect molecular similarity/diversity calculations using binary fingerprints and Tanimoto coefficients. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2000;40:163–166. doi: 10.1021/ci990316u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bajorath J. Integration of virtual and high-throughput screening. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:882–894. doi: 10.1038/nrd941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durant JL, Leland BA, Henry DR, Nourse JG. Reoptimization of MDL keys for use in drug discovery. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2002;42:1273–1280. doi: 10.1021/ci010132r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.PubChem. Bethesda: National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2013. [Accessed 2013 Nov 1]. Available from: http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klekota J, Roth FP. Chemical substructures that enrich for biological activity. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2518–2525. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yap CW. PaDEL-descriptor: an open source software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:1466–1474. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt MW, Baldridge KK, Boatz JA, Elbert ST, Gordon MS, Jensen JH, et al. General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J Comput Chem. 1993;14:1347–1363. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nye TM, Liò P, Gilks WR. A novel algorithm and web-based tool for comparing two alternative phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:117–119. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nye TM. Trees of trees: an approach to comparing multiple alternative phylogenies. Syst Biol. 2008;57:785–794. doi: 10.1080/10635150802424072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takane SY, Mitchell JB. A structure-odour relationship study using EVA descriptors and hierarchical clustering. Org Biomol Chem. 2004;2:3250–3255. doi: 10.1039/B409802A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]