Abstract

Budding yeasts are important expression hosts for the production of recombinant proteins.

The choice of the right promoter is a crucial point for efficient gene expression, as most regulations take place at the transcriptional level. A wide and constantly increasing range of inducible, derepressed and constitutive promoters have been applied for gene expression in yeasts in the past; their different behaviours were a reflection of the different needs of individual processes.

Within this review we summarize the majority of the large available set of carbon source dependent promoters for protein expression in yeasts, either induced or derepressed by the particular carbon source provided. We examined the most common derepressed promoters for Saccharomyces cerevisiae and other yeasts, and described carbon source inducible promoters and promoters induced by non-sugar carbon sources. A special focus is given to promoters that are activated as soon as glucose is depleted, since such promoters can be very effective and offer an uncomplicated and scalable cultivation procedure.

Introduction

Recombinant protein production in yeast has represented, in the last thirty years, one of the most important tools of modern biotechnology. The possibility to express a high amount of a single protein, separated from its original context, allowed major leaps forward in the understanding of many cellular functions and enzymes. However, since every host has its specific genetic system, species-specific tools have been established for each individual host/vector combination. In particular, promoters drive the transcription of the gene of interest and therefore are key parts of efficient expression systems to produce recombinant proteins. Furthermore expression of enzyme cascades and whole heterologous or synthetic pathways fully relies on a tool box of promoters with different sequence and properties.

Typically, there are two major choices concerning transcription of a gene of interest: inducible or constitutive promoters. The decision for one of these alternatives depends on the specific requirements of a bioprocess and the properties of the target protein to be produced. Constitutive expression, performed by a range of very strong promoters like P GAP (glycerinaldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) [1], P PGK1 (3-Phosphoglyceratekinase) [2] or P TEF1 (translation elongation factor) [3] from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is not always preferable, since recombinant proteins can have a toxic effect on their host organism at constantly high expression level.

Controllable gene expression can be achieved with inducible and derepressed promoters. Most of these inducible promoters are responsive to catabolite repression or react to other environmental conditions, such as stress, lack or accumulation of essential amino acids, ion concentrations inside the cell and others [4-6]. For practical applications, carbon source dependent promoters have the main advantage in the segregation of the host growth phase from the protein production phase, allowing maximizing growth before inducing a potentially burdening expression phase. Very recently, Da Silva & Srikrishnan have summarized important tools for controlled gene expression and metabolic engineering in S. cerevisiae, such as useful vectors, promoters and the procedure of chromosomal integration of recombinant genes [7].

In order to categorize a large amount of information, and due to its practical importance, in this review we describe the various promoters according to their basic behavior in relation to carbon sources. This includes the most essential regulatory elements and mechanisms of carbon source regulation as described by the main chapters of this review: glucose repression in yeast and promoters which are either induced by simple de-repression or induced by carbohydrates or other non sugar carbon sources.

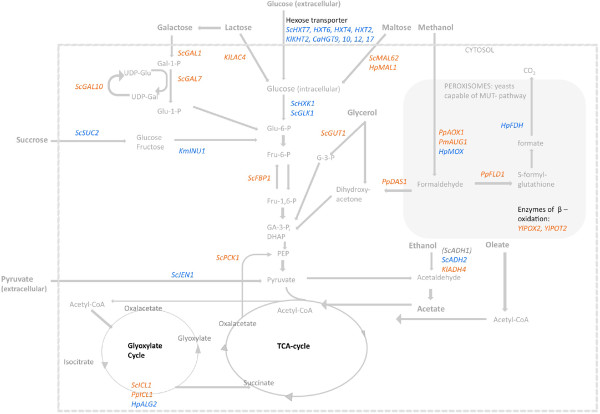

Wherever possible, special emphasis is given on the applicability of individual promoters in different hosts and application spectra for industrial protein synthesis. Figure 1 gives an overview of the particular target promoters described within this work and their localization in the yeast cell metabolism.

Figure 1.

Target genes for inducible (orange) and derepressed (blue) carbon source dependent promoters in yeasts and their localization in the metabolism.

Glucose repression in yeasts

Glucose is a favored carbon and energy source in yeast. Glucose repression and derepression essentially concern genes involved in oxidative metabolism and TCA (tricarboxylic acid) cycle, genes encoding for the metabolism of alternative carbon sources (e.g. sucrose, maltose, galactose), or genes for gluconeogenesis [8-10]. In presence of glucose, decrease in transcription or translation at the gene level or increase in protein degradation at the protein level are the most common mechanism to regulate the gene products involved [11].

In an early attempt to clarify carbon source dependence in S. cerevisiae, Gancedo has listed the elements of catabolite repression in yeast, focusing on regulatory elements on transcriptional level (Table 1), which was extended to additional proteins such as Oaf1 or Mig2 and Mig3.

Table 1.

Promoter interacting elements of catabolite repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (as reviewed in[10], [11], [12])

| Element | Designation | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Activator (DNA-binding proteins) |

Hap2/3/4/5 complex |

Activates transcription of proteins for respiratory functions |

| Gal4 |

Activates transcription of proteins for galactose and melobiose metabolism |

|

| Mal63 |

Activates transcription of proteins for maltose utilization |

|

| Adr1, Cat8, Sip4 |

Activates transcription of proteins for ethanol, glycerol and lactate utilization, as well as for gluconeogenic proteins |

|

| Oaf1 |

Activates transcription of proteins for oleate utilization |

|

| Repressor (DNA-binding proteins) |

Mig1 (Mig2, Mig3) |

Recruits Ssn6-Tup1 complex (repressor complex) in glucose repressed genes |

| Intermediate elements |

Snf1 |

Protein kinase (in complex with Snf4); derepression of glucose-repressed genes by phosphorylation of Mig1 |

| Glc7 |

Protein phosphatase; dephosphorylation of Snf1 |

|

| Glucose signaling |

Hxt-proteins |

Hexose transporter |

| Snf3 |

Glucose transporter |

|

| Rgt2 |

Glucose transporter |

|

| Hxk-proteins |

Hexokinase |

|

| Phosphorylation of glucose |

The current understanding of the mechanism of glucose derepression suggests that first of all the presence of glucose has to be signaled to the related genes. This signal transduction is likely performed by hexose transporters (HXT-gene products, Rgt2, Snf3) and hexokinases (HXK gene products). In yeast cells, a fully functional hexose transport is essential to provide functional glucose repression events, since repression is prompted by uptake and metabolism of glucose [13]. This is consistent with the phenotype of a HXT deletion strain [14], and also with the observation that the AMP/ATP ratio reflects the glucose level inside the cell (a high AMP/ATP ratio leads to activation of Snf1 [9], a kinase directly involved in gene regulation by carbon sources). However, most likely the processed metabolite of monosaccharides in the cell–glucose-6-phosphate–is the main signal that activates glucose repression [15].

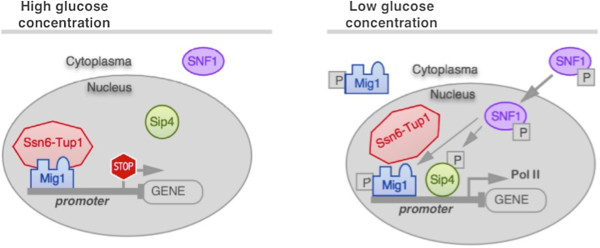

The event of glucose repression usually follows glucose level recognition, by repressors belonging to the Mig family comprising a group of C2H2-zinc-finger DNA-binding proteins. This family takes the name after Mig1, the most important repressor protein in this context, regulating the majority of glucose repressed genes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanism of glucose repression in yeast; modified from [16].

At high glucose level, Mig1 is transferred from the cytoplasm into the nucleus, where it binds a GC-rich recognition site in the promoter sequence (for consensus sequences see Table 2), and recruits a repressor complex consisting of Ssn6-Tup1 [17-19]. Using SUC2 promoter as a reporter system, it has been observed that the binding of Mig1 leads to a conformational change of the chromatin structure, further reinforced by Tup1 interaction with histones H3 and H4. Consequently, transcription initiating factors (such as Sip4) have no access to their binding sites [20].

Table 2.

DNA-motifs for regulator protein binding in natural promoter sequences of carbon source dependent S. cerevisiae promoters

Many glucose repressed genes, for example hexose transporters (e.g. MTH1, HXT4, HXK1), are solely affected by Mig1-repression. However, two more Mig repressors (Mig2 and Mig3) are reported to be involved in glucose repression, by partly assisting Mig1 in a synergistic way (e.g. ICL1, ICL2, GAL3, HXT2, MAL11, MAL31, MAL32, MAL33, MRK1, SUC2 are repressed by Mig1 and Mig2) or taking over complete repression events in some genes without the intervention of Mig1 activity (SIR2 is repressed by Mig3). The involvement of a particular Mig repressor in gene expression is strongly correlated to glucose concentrations inside the cell, as has been observed for HXT genes [10].

Generally, MIG1 from several yeast species are highly conserved, but there are some differences in regulation of homologous genes in different yeasts. One example is GAL4 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is regulated by Mig1 as described above, although GAL4 homologue LAC9 in Kluyveromyces lactis is triggered by a regulatory function of KlGAL1 and has no Mig1 binding site [18].

As soon as glucose is depleted, the protein kinase Snf1 is activated, mediating the release of Mig1 and the repressor complex by phosphorylation. Subsequently, Mig1 is exported from the nucleus, the promoter is derepressed and the gene expression gets activated [8]. Again, in the SUC2 expression model, the ATPase activity of the complex Swi/Snf triggers an ATP-dependent change of nucleosomal structure (chromatin remodeling) and facilitates the binding of transcription factors [20,23]. Consequently, activator proteins are binding to particular consensus sequences (Table 2) and initiate transcription [21,22,24].

Promoters derepressed by carbon source depletion

The peculiarity of all these promoters (Table 3), all induced at low glucose levels, lays in the lack of a proper induction for their activity. Such a behavior, in fact, represents also a reason for interest in potential applications, as the expression of the protein of interest does not start during cell growth, when the carbon source is typically abundant, but only at the late exponential phase, allowing de facto a regulated gene expression without external induction step. The advantage of these promoters is even more promising moving from batch cultivations to fed-batch processes: during the feeding phase, a strict control on growth rate (and, in turns, on carbon source concentration in the fermenter) can be easily achieved, hence having a tight control on recombinant protein production with relatively simple fermentation procedures.

Table 3.

Yeast promoters derepressed by gradual glucose consumption (repressed by glucose), and respective known regulator elements and binding sites

| Promoter | Protein function | Organism | Derepressed by: (strength) | Regulating sequence | DNA-binding target protein | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HXT7 |

High affinity hexose transporter |

S. cerevisiae |

Low glucose level (10-15×) |

No information available |

[25][26] |

|

| HXT2 |

High affinity hexose transporter |

S. cerevisiae |

Low glucose level (10-15×) |

-590 to -579 |

Rgt1 |

[27][28] |

| -430 to -424 | ||||||

| -393 to -387 | ||||||

| -504 to -494 |

Mig1 |

[27] |

||||

| -427 to -415 | ||||||

| -291 to -218 |

UAS |

[29] |

||||

| -226 to -218 |

Activator protein? |

[29] |

||||

| HXT4 |

High affinity hexose transporter |

S. cerevisiae |

Low glucose level |

-645 to -639 |

Rgt1 |

[28] |

| HXT6 |

High affinity hexose transporter |

S. cerevisiae |

Low glucose level (10×) |

No information available |

Mig2 |

[10] |

| KHT2 |

High affinity hexose transporter |

K. lactis |

Low glucose level (2×) |

No information available |

[30] |

|

| HGT9, 10, 12, 17 |

High affinity hexose transporter |

C. albicans |

Low glucose level |

No information available |

[31] |

|

| SUC2 |

Invertase |

S. cerevisiae |

Sucrose low glucose level (200×) |

-499 to -480 |

Mig1/2 |

[20] |

| -442 to -425 | ||||||

| -627 to -617 |

Sko1 |

|||||

| -650 to -418 |

UAS |

|||||

| -133 |

RNA-Pol II |

|||||

| ADH2 |

Alcohol dehyrogenase |

S. cerevisiae |

Low glucose level (100×) |

-319 to -292 |

Cat8 |

[24] |

| -291 to ?? |

Adr1 |

|||||

| JEN1 |

Lactate permease |

S. cerevisiae |

Low glucose level (10×), lactate |

-651 to -632 |

Cat8 |

[21][32] |

| -1321 to -1302 | ||||||

| -660 to -649 |

Mig1 |

[32] |

||||

| -1447 to -1436 | ||||||

| -739 to -727 |

Abf1 |

[32] |

||||

| MOX |

Methanol oxidase |

H. polymorpha |

Low glucose level, glycerol |

-245 to -112 |

Adr1 |

[33] |

| -507 to -430 |

UAS |

[34] |

||||

| AOX delta 6 |

Alcohol oxidase |

P. pastoris |

Low glucose level, glycerol |

|

deleted GCR1-site |

[33] |

| GLK1 |

Glucokinase |

S. cerevisiae |

Low glucose level (6×), ethanol (25×) |

-881 to -702 |

Gcr1 |

[35] |

| -572 to -409 |

URS |

|||||

| -408 to -104 |

Msn2/4 |

|||||

| HXK1 |

Hexokinase |

S. cerevisiae |

Low glucose level (10×), ethanol |

No information available |

[36] |

|

| ALG2 | Isocitrate lyase | H. polymorpha | Low glucose level | No information available | [37] | |

These promoter regions attract the binding of special transcription factors (e.g. Adr1), but as long as the carbon source is available, the chromatin structure is organized in such a way that the promoter is inaccessible to the activator protein. In the case of glucose, when its concentrations decreases, dephosphorylation of DNA-binding domains (as well as acetylation of histones H3 and H4) occurs, leading to a conformational change of the DNA region. Subsequently, the promoter region is accessible and gene expression can be activated by the activator protein without any induction signal [38].

Recently, Thierfelder and colleagues presented a new set of plasmids for Saccharomyces cerevisiae, containing several glucose dependent promoters induced at a low level of glucose (P HXK1 , P YGR243 , P HXT4 , P HXT7 ; [39]). In Pichia pastoris, a set of 6 novel glucose dependent promoters was described; promoters of hexose transporters, of a mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase and of some proteins with unknown function were represented in this list. Generally, all of them were also activated during glucose starvation [40].

Hexose transporter genes in S. cerevisiae and other yeasts

Hexose transporters in S. cerevisiae are encoded by 17 HXT genes. Some of them are induced (e.g. HXT1), whereas others are repressed by high levels of glucose (e.g. HXT2, HXT4, HXT7) [41]. In this section we will focus on the glucose-repressed fraction of HXT genes, that includes all high-affinity glucose transporters. In addition, high-affinity hexose transporters from other yeasts, that may have the potential of good promoter activity, will be discussed.

Hexose transporter proteins Hxt2, 4, 6 and 7 in S. cerevisiae are repressed by high glucose concentration, and induced when glucose concentration decreases below a certain level [39]. Two independent transcription repression mechanisms apply, mediated respectively by Mig repressor (high glucose level) or by Rgt1, a C6-zinc cluster (no glucose). Both proteins are responsible for recruiting the Ssn6-Tup1 complex [29]. While derepression upon Mig1 release is dependent by Snf1, Rgt1 dissociation requires Grr1-mediated phosphorylation, which is dependent from Mth1 and Std1 activities [42]. Interestingly, another regulatory complex, depending on pH and the corresponding altered calcineurin pathway, was hypothesized. This assumption is based on observations on HXT2 regulation: after shifting the media pH to 8, the expression of HXT2 reaches a plateau, while in snf1 mutant strains the expression was not completely inhibited. It was suggested that HXT2 promoter might be a target for the transcription factor Crz1, which is active at high pH and activates the calcineurin pathway, a response to environmental stress in yeast. Also related to pH shift, although to a lesser extent, is the induction of HXT7 and other glucose dependent proteins like Hxk1, Tps1, and Ald4. Overall, the response to alkaline stress of genes involved in glucose utilization suggests an impairment of glucose metabolism, probably due to a disturbed electrochemical gradient and subsequent uptake of nutrient through the cell wall: a sudden increase of pH value is a signal for the activation of stress responsive enzymes (e.g. superoxide dismutase, SOD) in order to maintain an appropriate pH for a functioning electrochemical gradient [27].

Many hexose transporter genes are not well described yet. Greatrix and colleagues compared the expression levels of HXT1-17. HXT13, for example, showed similar induction characteristics as HXT2 (i.e. induction at 0.2% w/v glucose). Furthermore, HXT6, closely related to HXT7, is induced at low glucose concentrations [43], but its expression is more dependent on the Mig2 repressor [10].

HXT7 seems to bind glucose with the highest affinity among all glucose transporters, and this fact is associated to a strong induction at low glucose level. The HXT7 promoter region turned out to be suitable for recombinant protein production in yeast and was compared to other yeast promoters (PTEF1, PADH1, PTPI1, PPGK1, PTDH3 and PPYK1) using lacZ as a reporter gene. Among them, PHXT7 was stated as the strongest promoter in continuous culture with limited glucose level [44]. Also in comparison with PADH1 for SUC2- and GFP-expression, respectively, PHXT7 produced promising results [25].

A variant of PHXT7 (PHXT7-391, 5′ deletion [26]), showing strong constitutive expression, was applied for overexpression of phosphoglucomutase 2 to improve anaerobic galactose metabolism [45].

P HXT2 was successfully used for the recombinant production of squalene synthase (ERG9), which plays an important role in synthesis of compounds for perfumes and pharmaceuticals [46].

As expected, the characterization of hexose transporters, and relative promoters, is poorly characterized in less conventional yeasts. Nevertheless, KHT1 and KHT2 from K. lactis, GHT1-6 from Schizosaccharomyces pombe, or HGT-genes from C. albicans have been described [47,48].

KHT1 and 2 represent a sort of genetic anomaly, as both are located in a polymorphic gene locus of RAG1[30], which encodes either a low (Kht1, Rag1) or a moderate affinity hexose transporter (Kht2). Therefore, P KHT2 is more interesting for application where a more sensitive glucose dependent promoter element is required. KHT2 turned out to be, sequence-wise, a close relative of HXT7 and is similarly regulated. It has to be considered that KHT2 is only weakly repressed by high glucose level and about 2-fold induced at concentrations below 0.1% (w/v) [49]. To our knowledge, the KHT2 promoter has not yet been applied for recombinant protein production so far.

The GHT genes from S. pombe not only encode glucose transporters (GHT1, 2 and 5) but also gluconate transporters (GHT3 and 4). GHT2 and 5 are not repressed by glucose, in contrast to GHT1, GHT3 and 4. Nevertheless, GHT5 is expected to be a high affinity glucose transporter, but so far no promoter studies about any of the GHT gene group of fission yeast is available [50].

Expression of another set of hexose transporters–the HGT genes–was studied in Candida albicans. In conjunction with derepressed genes (and promoters) HGT9, HGT10, HGT12 and HGT17 are most interesting for this review, since they are strongly induced at low glucose concentrations (0.2% w/v) [31].

Not surprisingly, also hexose transporters in the industrial workhorse Pichia pastoris attracted interest in the context of natural promoters and strain engineering aiming at methanol-free alcohol oxidase (AOX1)-promoter controlled expression. The only two known hexose transporters are PpHxt1 and PpHxt2. PpHxt1 is related to the S. cerevisiae HXT genes, is induced at high glucose concentrations and seems to play a minor role in P. pastoris. PpHxt2 is more species specific, has characteristics of a high-affinity glucose transporter, but is also responsible for main glucose transport during high glucose concentrations. Interestingly, a deletion of PpHXT1 leads to a hexose mediated induction of PAOX1[14], most probably due to the resulting low intracellular glucose concentration in such deletion variants.

Additionally, Prielhofer and colleagues described the use of several Pichia species’ hexose transporters as new promoter targets with green fluorescent protein (GFP) as reporter and, therefore, provided a potential alternative to methanol induced promoters [40] or engineered synthetic promoters, which also do not need methanol for induction [33].

SUC2 promoter

The SUC2 gene of S. cerevisiae encodes an invertase (beta-fructofuranosidase) and is inducible by sucrose. As for other glucose repressed genes, also the promoter of SUC2 enables expression to a high level without any external inducer. Similarly to HXT genes, derepression of SUC2 promoter takes place when the level of glucose (or fructose as well) is decreasing below a certain level (0.1% w/v); SUC2 promoter, interestingly, gets repressed again when glucose concentration drops to zero. In cultivations with glycerol as only (non-repressing) carbon source, the expression of SUC2 was shown to be 8-fold lower than expression in media with low glucose concentration [51]. The regulation of the SUC2-promoter is subjected to Mig1 and Mig2 binding sites on one hand (repression at high glucose level, [52]) and to Rgt1 repressor on the other hand (repression at lack of glucose, basal SUC2 transcription). At low glucose concentrations, Mig1/2, as well as Rgt1, are phosphorylated by the Snf1/Snf4 complex and thus transcription of SUC2 is initiated [53]. Additionally, the promoter activity can be further enhanced by sucrose induction but this is not essential for good promoter activity [51].

P SUC2 is a very suitable promoter for heterologous protein expression in yeast, and processes have been optimized for several applications, also above laboratory scale. For example, significant results for α-amylase expression by P SUC2 have been obtained using lactic acid as carbon source, a substrate supporting recombinant gene expression as well as cell growth by providing a fast way of energy production (lactate is converted to pyruvate and enters the TCA cycle). The advantage of an extended cell growth phase driven by a non repressing carbon source opened the possibility for the use of P SUC2 also in large scale applications [54].

In analogy, inv1 from Schizosaccharomyces pombe was subject of the development of a regulated expression system in S. pombe, since also the P inv1 is repressed by glucose (Scr1 mediated, which is another DNA binding protein recognizing GC-rich motifs within the promoter) and is further inducible by sucrose [55].

In Kluyveromyces marxianus, INU1, which is a closely related gene to SUC2 and encodes an inulase enzyme, responsible for fructose hydrolyzation, also carries two putative Mig1-recognition sites [18]. The promoter is activated by addition of sucrose or inulin, the derepression is controlled in a similar way to SUC2[56]. P INU1 was applied to several protein synthesis approaches in K. marxianus and S. cerevisiae, such as expression of inulase (inuE) or glucose oxidase (GOX) from Aspergillus niger[57,58].

JEN1 promoter

JEN1 encodes a transporter for carboxylic acids (e.g. lactate, pyruvate) in S. cerevisiae. JEN1 expression is repressed by glucose and derepressed when glucose level falls below 0.3 % (w/v), reaching a peak of activity at 0.1 % (w/v) glucose. Additionally, a weak P JEN1 activation by lactic acid was observed, using GFP as reporter gene [59].

The regulation of P JEN1 by the transcription factor Adr1 and the alternative carbon source responsive activator Cat8 was confirmed [60]. Two Mig1 binding sites in the upstream sequence of JEN1 were identified [32,61]. Subsequently, however, Andrade and colleagues published an alternative mechanism of regulation, proposing that Jen1 is post-transcriptionally regulated by mRNA degradation, rather than by Mig1 mediated repression [62].

JEN1 promoter has been successfully applied to Flo1 expression, a protein involved in flocculation processes [59].

ADH2 promoter

A very popular promoter, used in several yeasts, is the promoter of the alcohol dehydrogenase II gene from S. cerevisiae[63]. In contrast to the widely used constitutive yeast ADH1 promoter, P ADH2 is strongly repressed in presence of glucose, and derepressed as soon as the transcription factor Adr1 binds to the upstream activating sequence UAS1 of P ADH2 . Adr1 is dephosphorylated when glucose is depleting, and the cell switches to growth on ethanol (Adr1 dephosphorylation appears to be Snf1-dependent). There is also a second glucose dependent UAS (namely UAS2), less characterized but likely activated by Cat8 in a synergistic way with Adr1, and thus identified as a CSRE sequence (carbon source responsive element) [24,64]. Furthermore, some other protein kinases, such as Sch9, Tpk1 and Ccr1, that also derepress P ADH2 , influence the expression level of ADH2. Interestingly, there is no typical Mig1-binding site in the ADH2 promoter sequence; glucose repression is mainly mediated by the Glc7/Reg1 complex [11].

The potential of P ADH2 was evaluated and compared to the inducible S. cerevisiae promoters P CUP1 and P GAL1 and turned out to yield the highest level of expression after 48 hours [65].

S. cerevisiae ADH2 promoter is not the only alcohol dehydrogenase promoter used in expression studies. P adh from S. pombe, (adh shows high homology with S. cerevisiae Adh2 at the protein level) is a frequently used promoter in fission yeast, but is described as being constitutively expressed [66].

The related ADH4 gene from K. lactis is characterized by a strong ethanol induction, and is therefore separately described in Section Induction by non-sugar carbon sources.

A Pichia-specific ADH2 promoter was isolated from Pichia stipitis and is–in contrast to ScADH2–not glucose- but oxygen-dependent (induction at low O2 level). This PsADH2 promoter was used in the heterologous host Pichia pastoris for the expression of Vitreoscilla hemoglobin (VHb) [67].

HXK1, GLK1 promoter

Hexokinase (HXK1) and Glucokinase (GLK1) in S. cerevisiae are involved in the first reaction of glycolysis, the phosphorylation of glucose, and are activated when the cell is entering a starvation phase or when switched to another carbon source [36]. Both enzymes are not expressed in presence of high glucose levels (subjected by a classical Mig1 repression; [10]), but become derepressed as soon as glucose is depleting. In case of GLK1, a 6-fold increase of expression level by derepression and further 25-fold induction by ethanol was reported [35]. HXK1, in comparison, is 10-fold repressed by glucose in dependence of Hxk2 protein [36] and was listed as one of Thierfelder’s glucose dependent promoters with average strength, when it is induced at low glucose concentration [39].

P HXK1 , for instance, was successfully applied to the expression of a GST-cry11A fusion protein in S. cerevisiae[68] or, in more recent years, to the expression of bovine β-casein [69]. In case of P GLK1 , no application in terms of recombinant protein production was reported.

Carbon source dependent inducible promoters

Other promoters are derepressed in absence of glucose and additionally need to be induced by an alternative carbon source to obtain full expression efficiency (Table 4). The inducer is either produced by the cell in course of time or has to be provided in the medium.

Table 4.

Yeast promoters induced in dependence of carbon sources and their regulator elements

| Promoter | Protein function | Organism | Induced by (strength) | Repressed by | Regulating sequence | DNA-bindingtarget protein | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAL1 |

Galactose metabolism |

S. cerevisiae |

Galactose (1000×) |

Glucose |

-390 to -255 |

Gal4 |

[70] |

| -201 to -187 |

Mig1 |

[71] |

|||||

| GAL7 |

Galactose metabolism |

S. cerevisiae |

Galactose (1000×) |

Glucose |

-264 to -161 |

Gal4 |

[70] |

|

K. lactis |

Galactose |

No information available |

|||||

| GAL10 |

Galactose metabolism |

S. cerevisiae |

Galactose (1000×) |

Glucose |

-324 to -216 |

Gal4 |

[70] |

| Galactose metabolism |

C. maltosa |

Galactose |

Glucose |

No information available |

|||

| PIS1 |

Phosphoinositol synthase |

S. cerevisiae |

Galactose, hypoxia (2×), zinc depletion (2×) |

(glycerol) |

-149 to -138 |

Rox1 |

[72] |

| Gcr1 | |||||||

| -224 to -205 |

Ste12 |

||||||

| Pho2 | |||||||

| -184 to -149 |

Mcm1 (2×) |

||||||

| LAC4 |

Lactose metabolism |

K. lactis |

Lactose, galactose (100×) |

- |

-173, -235 |

RNA-Pol II |

[73] |

| -437 to -420 |

Lac9 |

||||||

| -673 to -656 | |||||||

| -1088 to -1072 | |||||||

| MAL1 |

Maltase |

H. polymorpha |

Maltose sucrose |

Glucose |

No information available |

[74] |

|

| MAL62 |

Maltase |

S. cerevisiae |

Maltose sucrose |

Glucose |

-759 to -743 |

Mal63 |

[75][11] |

| AGT1 |

Alpha-glucoside transporter |

Brewing strains S. cerevisiae, S. pastorianus |

Maltose sucrose |

Glucose |

Divergent (strain dependent) |

Mig1 |

[76] |

| Malx3 | |||||||

| ICL1 |

Isocitrat lyase |

P. pastoris |

Ethanol (200×) |

Glucose |

No information available |

[77] |

|

|

C. tropicalis |

Ethanol |

Glucose |

No information available |

[78] |

|||

|

S. cerevisiae |

Ethanol (200×) |

Glucose |

-397 to -388 |

Cat8, Sip4 |

[21][79] |

||

| -261 to -242 |

URS |

[79] |

|||||

| -96 |

RNA-Pol II |

[77] |

|||||

| FBP1 |

Fructose-1,6- bisphosphatase |

S. cerevisiae |

Glycerol, acetate, ethanol (10×) |

Glucose |

-248 to -231 |

Hap2/3/4 (2×) |

[80] |

| No information available |

Cat8, Sip4 |

[21] |

|||||

| PCK1 |

PEP carboxykinase |

S. cerevisiae |

Glycerol, acetate, ethanol (10×) |

Glucose |

-480 to -438 |

Cat8, Sip4 |

[21][80] |

| PEP carboxykinase |

C. albicans |

Succinate, casaminoacids |

Glucose |

-320 to -123 |

Hap2/3/4 (2×) |

[80] |

|

| -444 to -108 |

Mig1 (3×) |

[80] |

|||||

| GUT1 |

Glycerol kinase |

S. cerevisiae |

Glycerol, acetate, ethanol, oleate |

Glucose |

-221 to -189 |

Adr1 |

[81] |

| -319 to -309 |

Ino2/4 |

[81] |

|||||

| CYC1 |

Cytochrome c |

S. cerevisiae |

O2 (200×), lactate (5-10×) |

Glucose |

No information available |

[82] |

|

| ADH4 |

Alcohol dehyrogenase |

K. lactis |

Ethanol |

- |

-953 to -741 |

UAS |

[83] |

| AOX1, 2 |

Alcohol oxidase |

P. pastoris |

Methanol |

Glucose |

-414 to -171 |

Mxr1 |

[84][85] |

| AUG1, 2 |

Alcohol oxidase |

P. methanolica |

Methanol |

Glucose |

No information available |

[84] |

|

| DAS1 |

Dihydroxy- acetone- synthase |

P. pastoris |

Methanol |

Glucose |

-980 to -1 |

Mxr1 |

[84] |

| FDH |

Formate dehydrogenase |

H. polymorpha |

Methanol |

Glucose |

No information available |

[84] |

|

| FLD1 |

Formaldehyde dehydrogenase |

P. pastoris |

Methanol, methylamine, choline |

Glucose |

No information available |

[84] |

|

| POX2 |

Peroxisomal protein |

Y. lipolytica |

Oleate |

Glucose |

No information available |

[86] |

|

| PEX8 |

Peroxisomal protein |

P. pastoris |

Oleate methanol (3-5×) |

Glucose |

-1000 to -1 |

Mxr1 |

[87][88] |

| INU1 |

Inulase |

K. marxianus |

Fructose, Inulin, Sucrose |

Glucose |

-271 to -266 |

RNA-Pol II |

[56] |

| -163 to -153 | Mig1 | [58] | |||||

Galactose, maltose, sucrose, and some other fermentable carbon sources, as well as oleate, glycerol, acetate or ethanol, as non-fermentable carbon sources, can be considered as alternative inducers for regulated gene expression, since the genes that are involved in the particular metabolism are repressed, as long as the preferred carbon source glucose is available.

Induction by carbohydrates

Induction by galactose

The promoters of the S. cerevisiae GAL genes are the most typical and most characterized examples of galactose-inducible promoters. They are strongly regulated by cis-acting elements, depending on glucose level, whereupon galactose is acting as the main inducer [70].

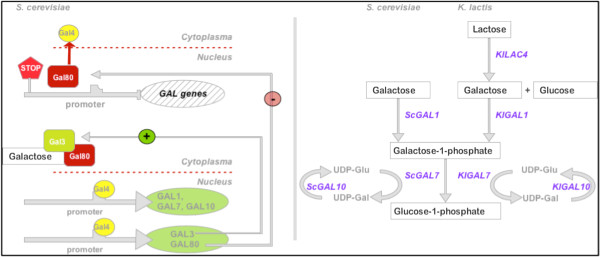

Gal6 and Gal80 are negative regulators of Gal4, which is classified as the activator of the main proteins of galactose utilization pathway GAL1 (galactokinase), GAL7 (α-d-galactose-1- phosphate uridyltransferase) and GAL10 (uridine diphosphoglucose 4-epimerase) [89], as shown in Figure 3. Negative regulators for GAL genes have been shown to work in synergy with Mig1 [71]. Gal3 is expected to act as a signal transducer that forms a complex with galactose and Gal80, further releasing Gal4 inside the nucleus and activating GAL1, 7 and 10 expression [90,91].

Figure 3.

Regulation and function of the GAL genes.

P GAL1 and P GAL10 are widely used in S. cerevisiae for recombinant protein production, for which different cultivation protocols have been developed. The crucial point is the maintenance of a low glucose level, which is important for efficient induction [92]. Since also galactose concentration decreases during activation of the galactose utilizing pathway, the inducing effect diminishes over time. The high cost of galactose feeding demands a strategy to overcome this problem [93,94]. Several authors have generated Saccharomyces cerevisiae gal1 mutant strains that lack the ability to use galactose as a carbon source. Furthermore, MIG1 and HXK2 were disrupted to circumvent glucose repression [91,92,94]. Consequently, P GAL10 is induced even at low galactose concentrations, while presence of glucose does not affect promoter activity. In this case, the optimum concentration of galactose for induction was reported to be 0.05% (w/v) for expressing human serum albumin [92]. Interestingly, Ahn and colleagues found out that P GAL10 works under anaerobic conditions as well, and easily keeps up with other promoters (P PGK , P PDC or P ADH1 ) for fermentative application. Therefore, P GAL10 is another strong promoter suitable, for example, for microaerobic or anaerobic processes like bioethanol production [95].

Other yeast genera than Saccharomyces, like Kluyveromyces or Candida, present homologous protein functions for galactose utilization. In K. lactis, Lac9 resembles the function of Gal4 and is blocked by KlGal80, which is very similar to Gal80 from S. cerevisiae. In contrast to S. cerevisiae, there is no Gal3 equivalent in K. lactis. Galactose metabolism is mediated by KlGal1, KlGal7 and KlGal10 [11][96]. Besides, KlLac9 additionally activates KlLac4, a β-galactosidase, responsible for lactose-utilization (see also Section Induction by lactose). In contrast to S. cerevisiae, the regulatory genes of the K. lactis GAL expression are not strongly repressed by glucose.

Gonzalez and colleagues took advantage of the resembling lac-gal-regulon in K. lactis and applied the S. cerevisiae promoter P GAL1 to express Trigonopsis variabilis D-aminoacid oxidase (DAO1) in K. lactis[97].

GAL1 and GAL10 promoters of Candida maltosa have been successfully isolated, with the intention to create a functional expression system in this species, and were tested with K. lactis LAC4 as a reporter gene. Both promoters were applied to high level expression of several cytochrome P450s, encoded by the ALK gene cluster. P GAL1 and P GAL10 of C. maltosa were integrated into a low-copy and a high-copy plasmid, respectively, and CO-spectra were measured to prove the P450 expression. In the low-copy plasmid the authors obtained an expression level of 0.96–1.21 nmol/mg wet cell weight, whereas quite notably the high-copy plasmid enabled a 3-fold amount of expressed protein [98]. Other important expression hosts, such as P. pastoris, lack a functional pathway and the respective promoters for galactose metabolism.

PIS1 (phosphatidylinositol-synthase, protein involved in the synthesis of phospholipids) presents an unusual behavior, since it is not subjected to conventional glucose repression in S. cerevisiae, but is known for increased transcription as soon as galactose is present in the medium. Interestingly, the presence of glycerol leads to a significant decrease of expression, while the expression level was not affected in glucose-containing medium. The regulatory mechanism is mainly mediated by Mcm1, a DNA-binding protein, which further interacts with another modulating protein, Sln1 [99]. Additionally, PIS1 is repressed at anaerobic conditions [72] and is responsive to zinc (increased PIS1 expression after zinc depletion was reported; [100]). Hence, PIS1 provides a range of possibilities for regulated gene expression with one single promoter.

There are no PIS1 promoter applications reported yet, but Stadlmayr and colleagues described the Pichia pastoris P PIS1 in a comparative Pichia promoter study, where the promoter activity was accounted for being rather low, when different carbon sources (glucose, glycerol and methanol) were tested [101,102].

Induction by lactose

A distinctive feature of K. lactis is the ability to use lactose as a carbon source. Primarily the proteins of lactose and galactose metabolism are co-regulated by the lac-gal-regulon. A lactose permease (Lac12) is transporting lactose into the cell, where it is cleaved to glucose and galactose by a β-galactosidase (Lac4). Subsequently, the galactose metabolism is activated, involving genes (KlGal1, KlGal7 and KlGal10) corresponding to the S. cerevisiae counterparts described above [103].

The gene products of lactose and galactose metabolisms are controlled by an activator protein Lac9 (= KlGal4) and all of them are induced by lactose or galactose.

Interestingly, the lactose utilization genes are not repressed by glucose in K. lactis, while the galactose metabolism is weakly repressed [11,104]. The low catabolite repression, along with strong induction potential, is one of the advantages of many K. lactis promoters.

The promoter P LAC4 has been successfully used for recombinant protein production in K. lactis[105]. Significant applications consisted, for example, in the controlled expression of prochymosin, important in the context of cheese production [106], or in the expression of Rhizopus oryzae α-amylase [107]. The consumption of the inducer is a problem in practical applications of P LAC4 also in this organism: K. lactis strains with disrupted KlGAL1 were generated to prevent an early consumption of the inducer, following a similar strategy as the one showed for S. cerevisiae[108,109].

An interesting side effect is also the occurrence of Pribnow box-like sequences in the native promoter, which enables P LAC4 to constitutively express heterologous proteins in E. coli. However, this feature is rather unwelcome for a typical protein expression process, since a prior correct assembling of the constructs in E. coli as an intermediate host can be problematic. With the goal to circumvent this inconvenience, a set of P LAC4 -variants, mutated in Pribnow box-like sequence, has been developed. Such a promoter modification allowed to successfully express bovine enterokinase, whose expression had been problematic before [110].

Induction by maltose

Maltose utilization is a feature of several yeasts, among which S. cerevisiae, Hansenula polymorpha (the only methylotrophic species for which this phenotype was reported) and K. lactis. The MAL gene group is repressed by glucose and induced by maltose and sucrose. There are up to 5 unlinked MAL loci in yeast (MAL1, MAL2, MAL3, MAL4, MAL6), and each of them consists of a permease (MALx1), a maltase (MALx2) and an activator protein (MALx3) [74]. The promoter region for MALx1 and MALx2 is a bidirectionally active intergenic region, consisting of an UAS, 2 symmetrically organized TATA-boxes, 2 Mig1 binding sites and intermediate tandem repeats, which are assumed to regulate the expression level of MALx1 and MALx2. This bidirectional promoter was applied to the simultaneous expression of reporter genes MEL1 and lacZ [111]. Several authors highlighted the potential of MAL-promoters in expression vectors for regulated protein synthesis, by using maltose as an inducer [112]. For example, using P MAL62 from S. cerevisiae provided similar expression results as P GAL1 , when LexA was expressed as a reporter gene. Notably, background expression driven by P MAL62 was definitely higher (compared to P GAL1 ) under non-repressing and non-inducing conditions. Nevertheless, the expression of a very toxic protein, cyclin A from Drosophila was efficient for the maltose regulated protein synthesis by P MAL62 compared to its constitutive expression with P ADH1 [113].

AGT1, which encodes a α-glucoside transporter, is highly homologous to the S. cerevisiae MAL61. P AGT1 sequence from several beer yeast strains (S. cerevisiae, S. pastorianus), was recently analyzed. AGT1 is repressed by glucose in a similar manner in all tested strains (it showed to be Mig1-dependent), while derepression and maltose induction strength are strain-dependent, probably due to a certain divergence in AGT1 promoter sequences. The regulation of maltose induction is dependent by the MAL activator proteins, [76].

In H. polymorpha, the native P MAL1 performed very well–also in comparison to the commonly used P MOX , especially when the promoter was induced by sucrose. Furthermore, H. polymorpha P MAL1 was transferable to another maltose utilizing yeast species–S. cerevisiae -, for recombinant expression of native maltase [75].

Induction by non-sugar carbon sources

Induction and derepression by ethanol, glycerol or acetate

Glycerol is a very relevant inducer of many promoters; interestingly, glycerol is often used to “derepress” a promoter, prior to actively induce transcription activation by another inducer, such as ethanol, methanol or acetate. Most of related genes are involved in gluconeogenesis. Below, the most important promoter sequences belonging to this group will be described.

One meaningful promoter in this category is the promoter of ICL1, which encodes for isocitrate lyase, a key enzyme of the TCA and glyoxylate cycle, enabling the cell to grow on non-fermentable carbon sources. It is repressed by glucose, derepressed by depletion of glucose and strongly induced by ethanol or acetate. P ICL1 is mainly regulated by the two C6-zinc finger proteins Cat8 and Sip4 (see Table 1), which bind to a UAS as soon as glucose is depleted and ethanol or acetate are available [79].

ICL1 promoter sequences from several yeasts such as S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris, Yarrowia lipolytica or Candida tropicalis are well established and frequently applied to protein expression [77,78,114]. In K. lactis, ICL1 is assumed to be regulated without a Mig1 repressor, even if the derepression and induction are mediated by the Snf1/Snf4 complex [115]; it is still unclear if other repressor proteins are involved with URS regulation of ICL1.

In S. cerevisiae, the 5′ upstream region of ICL from Candida tropicalis is often used as an inducible promoter; its optimum glucose concentration for derepression was measured at 0.5% (w/v), when Rhizopus oryzae lipase was expressed [116]. While expressing secreted β-galactosidase, the induction with acetate leads to a 300-fold enhancement of product activity. It needs to be mentioned that this level of expression is protein-dependent (e.g. expression of lipase yielded only a fraction of the protein amount after induction compared to its expression under derepressed promoter condition [116]). Therefore, the volumetric activity of an expressed enzyme does not necessarily correlate with the strength of transcription. This might also be a reason why in Pichia pastoris the native P ICL1 was praised as a good alternative for methanol free protein production [77], while on the other hand, according to a recent review, the transcription levels of this promoter in Pichia pastoris appear to be lower than with the classic P AOX1 or P GAP [117].

The P ICL1 of Y. lipolytica is a standard promoter used for this host and was reported to be induced about 10-fold by ethanol, when β-galactosidase was expressed [114]. Besides, it has been reported to be inducible by fatty acids and alkanes [118].

A special case is represented by ALG2 in H. polymorpha, which encodes another isocitrate lyase with 50–60% sequence homology to ICL of other yeasts. The promoter of ALG2 is activated by derepression at low glucose level (0.2% w/v) rather than by ethanol induction [37].

The promoter region of FBP1, encoding fructose-1, 6-bisphosphatase, was analyzed in several occasions, concerning upstream regulating sequences [80,119]. P FBP1 is repressed by sugars like glucose, shows a Mig1 binding site in the upstream sequence from -200 to -184 [11] and carries a Cat8 and Sip4 recognition site (UAS2) for activation of transcription when non-fermentable carbon sources (ethanol, acetate, glycerol) are available [21,22]. Additionally, P FBP1 was reported to have another regulatory sequence (UAS1), showing a different sensitivity to glucose than UAS2 [119], a genetic arrangement unique within this group of presented promoters.

Within the group of budding yeast, no practical applications of P FBP1 have been found: only the fbp1+ promoter from fission yeast was mentioned several times as an opportunity for controlled gene expression in S. pombe[120]. However, this might also be explained by the fact that Fbp1 activity in glycolysis is also strongly regulated on the protein level, and not mainly by transcription.

The PEP carboxykinase (PCK1) promoter, which is inducible in absence of glucose by glycerol, ethanol, acetate or lactate as well, was already isolated from several yeasts, like S. cerevisiae[80] or C. albicans: in particular, the P CaPCK1 gained popularity within Candida community. By means of the S. cerevisiae PCK1 promoter, Cat8 and Sip4 have been identified as responsible activator proteins for transcription as well [21]. It has however to be mentioned, that, at least in the case of CaPCK1 promoter, other inducers, such as casamino acids or succinate, have been proved to be more efficient regarding expression of LAC4 in C. albicans[121]. This observation was confirmed by an example, where the CaPCK1 promoter was applied to CaCse4-expression in C. albicans by succinate induction [122] and furthermore by CaCdc42-expression, which was driven by casamino acid induction [123].

Technically speaking, also the promoters of the gluconeogenetic proteins Acs1 (acetyl-CoA-synthase) or Mls1 (malate synthase) belong to this group, and have been characterized regarding their upstream regulatory sequences [124,125], but to the best of our knowledge they have not been applied for protein production yet.

The S. cerevisiae glycerol kinase (GUT1) is another example of a gene whose expression is mainly induced by glycerol, but also by ethanol, lactate, acetate or oleate. Complete depletion of glucose is necessary to derepress the promoter. The regulation mechanism is subjected to Adr1 and Ino2/4 activation, and repression by Opi1 activity. Even if there might be a Mig1-binding site, this repressor seems to play a minor role [81]. The use of the P. pastoris P GUT1 promoter was proposed quite recently and was successfully applied to expression of β-lactamase as a model protein [126].

The CYC1 (cytochrome c) gene product is an important element of the electron transport in S. cerevisiae and is repressed under anaerobic conditions and in presence of glucose. The intracellular heme level mediates the O2-dependent activation of UAS1 element in the CYC1 promoter region by binding of Hap1. UAS2 binds the Hap2/3/4/5 complex, and is activated by any non-fermentable carbon source [82]. Induction with O2 increases expression about 200-fold, whereas lactate-induction is not as effective (5–10 fold) [127].

In the respiratory yeast K. lactis, CYC1 is expressed to a high level too, but glucose repression is also in this case almost irrelevant because the major part of expression is fulfilled by O2-induction and UAS1 activation [128].

Cytochrome c is a highly conserved protein in several eukaryotes, and is therefore easy to transfer between different yeast species. In many S. cerevisiae vectors, the terminator of CYC1 gene is used for termination of transcription. Nonetheless, the promoter region of CYC1 is not particularly exploited, in any case often evaluated as hybrid promoter with GAL10 (UASG-GAL10/CYC1). This construct consists of 365 bp of GAL10, including a UAS sequence, and the core promoter of CYC1 (TATA-Box, transcription start site and first four basepairs of CYC1 gene). Da Silva & Bailey have applied such hybrid promoter, among others, in order to determine the influence of different promoter strengths on fermentative protein expression in yeast, and as a result UASG-GAL10/CYC1 promoter showed moderate strength compared to P GAL1 , when it was induced with galactose [129]. Nevertheless, one example of successful application of the hybrid promoter is the expression of HbsAg and preS2-S in S. cerevisiae for HBV vaccine preparation [130].

The use of the K. lactis ADH4 promoter was patented by Falcone and colleagues [131]. It is located in the mitochondria, is not repressed by glucose but strongly induced by ethanol. The important control region for regulation of ethanol induction was found to be located between -953 and -741 [83].

For the sake of completeness, it has to be mentioned that also the S. cerevisiae ADH2 promoter is induced by ethanol, but due to its efficient repression/derepression mechanism this promoter was described in Section Promoters derepressed by carbon source depletion. The same applies to the hexokinase genes HXK1 and GLK1.

Induction by methanol

This promoter type has been sufficiently reviewed in the past by several authors, and will therefore be mentioned only briefly. For further detailed information, we refer the reader to the corresponding literature (see below).

The use of methanol as an inducer is confined to methylotrophic yeasts, like Pichia pastoris, Pichia methanolica, Hansenula polymorpha or Candida boidinii, which are able to metabolize methanol as a carbon source [132]. The most established promoters comprise those from genes encoding alcohol oxidases (namely P AOX1 and -2 in P. pastoris, P AUG1 and -2 in P. methanolica, P MOX in H. polymorpha, P AOD1 in C. boidinii), dihydroxyacetone synthases (P DAS1 and P DAS2 in P. pastoris, P DAS in H. polymorpha, P DAS1 in C. boidinii) and formate dehydrogenases (P FDH in H. polymorpha, P FDH1 in C. boidinii). All of them are elements of the methanol utilization (MUT) pathway, and are repressed by glucose and strongly induced by addition of methanol (importantly, they are also derepressed by a non-fermentable carbon source, e.g. glycerol). Especially H. polymorpha P MOX shows a significant derepression effect in presence of glycerol, since protein activity is already 80% of the methanol induced status. A special case in this context is the group of formaldehyde dehydrogenases (P FLD1 in P. pastoris, P FLD in P. methanolica, P FLD in H. polymorpha), which are not only negatively regulated by glucose, but additionally are responsive to methylamine or choline induction [84,101,133].

At present, a set of engineered promoter variants based on these natural sequences of the MUT pathway genes have been developed. Such modified promoters (e.g. P MOX in H. polymorpha and P AOX1 in P. pastoris) are no longer methanol inducible, showing in most cases either an inducible phenotype from molecules other than methanol, or a more pronounced derepressed phenotype [134,135].

In case of P FLD , Resina and colleagues exploited an advantageous characteristic of the promoter (P FLD is inducible by methylamine) thereby circumventing methanol induction [136].

PEX8 is a peroxisomal protein (formerly PER3) in P. pastoris, whose promoter leads to a moderate expression level on glucose. A weak induction by methanol or oleate (3–5 fold) has been reported [87,118]. The main regulator protein in P PEX8 is Mxr1, which is characteristic for all methanol inducible genes in Pichia and binds the promoter in a 5′-CYCCNY-3′ motif [88]. It remains to be demonstrated if multiple Mxr1 binding sites such as in the P DAS and P AOX promoters would increase P PEX8 strength.

P PEX8 was chosen for instance in the framework of Pex14 characterization, and was applied under methanol- and oleate-inducing conditions, respectively [137].

Induction by oleate

Oaf1 and Pip2 are important DNA-binding proteins for the transcriptional activation of oleate responsive proteins in yeast. In many cases (e.g. CTA1; peroxisomal catalase, POX1; peroxisomal acyl CoA oxidase, FOX3; 3-ketoacyl CoA thiolase, PEX1; peroxisomal biogenesis factor 1) also Adr1 is involved in initiating gene transcription [138]. Most of these proteins are functionally connected to the peroxisomes and are mainly involved in β-oxidation. For example POX1, FOX3 (= POT1), ECI1 and PEX11 are strongly induced by oleate and repressed by glucose, whereupon a significant derepression already occurs in presence of glycerol. Besides, PEX5, CRC1, CTA1 and QDR1 are also induced by oleate, although at a lower level [12].

In terms of industrial applications, no relevant oleate inducible promoters have been reported for S. cerevisiae so far. Up to now, especially, POX2 and POT1 promoters from Y. lipolytica, which are also activated by oleate, have been validated for recombinant protein synthesis of lipase in Y. lipolytica[138]. In the meantime P POX2 has been frequently used, especially, when hydrophobic substrate conditions were required. The performance of P POX2 was further improved, testing human interferone alpha 2b expression, by co-feeding glucose at a limited rate during induction with oleate [139].

Conclusions

This review describes the current state of art for a set of potential promoters for controlled protein synthesis, out of several yeasts. Especially in case of inducible promoters, the presented genetic tools are already well established, with several examples now summarized within this work. Nevertheless, also some less popular promoters show interesting features, which might be enhanced by promoter engineering: such a technique, despite its potential, is not yet very common for promoter improvements.

Generally, any gene subjected to derepression at low glucose concentrations, opens up the potential of carrying a strong promoter sequence. Referring to transcriptome analysis covering 31% of the genome [140,141], about 163 genes from S. cerevisiae were upregulated at glucose-limited conditions. Many of these genes are still poorly characterized, and their function is not known yet. For instance, YGR243 promoter from S. cerevisiae was already introduced as an interesting promoter tool [39], whereupon P YGR243 could easily keep up with P HXK1 .

A comprehensive knowledge of promoter elements is also helpful in terms of the development of synthetic promoters, since this field of research is relatively new, but gained increased popularity within the last ten years. Sequences of strong natural promoters are combined, and transcription factor binding sites are deleted or amplified with the objective of obtaining a new, more convenient promoter sequence [142].

Very recently, Blazeck and colleagues presented a set of synthetic yeast promoters by assembling very strong transcriptional enhancing elements (coming from CLB2, CIT1, GAL1, respectively) with the core of a particular promoter. The essential finding was a direct proportion between the number of additional UAS and promoter activity [143]. Interestingly, most yeast promoter studies are still focused on endogenous promoters and rarely on heterologous applications or fully orthogonal systems.

A broad knowledge of different potentials of promoter elements paves the way for creating a comprehensive promoter tool box and facilitates protein synthesis for appropriate applications.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KW and AC collected all the relevant publications, arranged the general structure of the review and drafted the text; AC, AG and MW revised and amended the general flow. KW produced tables and figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Katrin Weinhandl, Email: katrin.weinhandl@acib.at.

Margit Winkler, Email: margit.winkler@acib.at.

Anton Glieder, Email: anton.glieder@acib.at.

Andrea Camattari, Email: andrea.camattari@tugraz.at.

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Federal Ministry of Economy, Family and Youth (BMWFJ), the Federal Ministry of Traffic, Innovation and Technology (bmvit), the Styrian Business Promotion Agency SFG, the Standortagentur Tirol and ZIT–Technology Agency of the City of Vienna through the COMET-Funding Program managed by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency FFG and European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n° 289646.

References

- Waterham HR, Digan ME, Koutz PJ, Lair SV, Cregg JM. Isolation of the Pichia pastoris glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene and regulation and use of its promoter. Gene. 1997;186:37–44. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00675-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuite M, Dobson MJ, Roberts NA, King RM, Burke DC, Kingsman SM, Kingsman AJ. Regulated high efficiency expression of human interferon-alpha in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1982;1(5):603–608. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatignol A, Dassain M, Tiraby G. Cloning of Saccharomyces cerevisiae promoters using a probe vector based on phleomycin resistance. Gene. 1990;91(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90159-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Zhang LM, Zhang KQ, Deng JS, Prändl R, Schöffl F. Effects of heat stress on yeast heat shock factor-promoter binding in vivo. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2006;38(5):356–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2006.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller A, Valesco J, Subramani S. The CUP1 promoter of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is inducible by copper in Pichia pastoris. Yeast. 2000;16:651–656. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(200005)16:7<651::AID-YEA580>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solow SP, Sengbusch J, Laird MW. Heterologous protein production from the inducible MET25 promoter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Prog. 2005;21:617–620. doi: 10.1021/bp049916q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva NA, Srikrishnan S. Introduction and expression of genes for metabolic engineering applications in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012;12:197–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2011.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M. Glucose repression in yeast. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:202–207. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WA, Hawley SA, Hardie DG. Glucose repression/derepression in budding yeast: SNF1 protein kinase is activated by phosphorylation under derepressing conditions, and this correlates with a high AMP: ATP ratio. Curr Biol. 1996;6(11):1426–1434. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(96)00747-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westholm J, Nordberg N, Murén E, Ameur A, Komorowski J, Ronne H. Combinatorial control of gene expression by the three yeast repressors Mig1, Mig2 and Mig3. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:601–614. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancedo JM. Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62(2):334–361. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.334-361.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpichev IV, Durand-Heredia JM, Luo Y, Small GM. Binding characteristics and regulatory mechanisms of the transcription factors controlling oleate-responsive genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(16):10264–10275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708215200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özcan S. Two different signals regulate expression and induction of gene expression by glucose. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(49):46993–46997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Zhang W, Zhou X, Bai P, Cregg JM, Zhang Y. Catabolite repression of Aox in Pichia pastoris is dependent on hexose transporter PpHxt1 and pexophagy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(18):6108–6118. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00607-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppi S, Michelson T, Viigand K, Alamäe T. Repression vs. activation of MOX, FMD, MPP1 and MAL1 promoters by sugars in Hansenula polymorpha: the outcome depends on cell’s ability to phosphorylate sugar. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012;13(2):219–232. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedbacker K, Carlson M. SNF1/AMPK pathways in yeast. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2408–2420. doi: 10.2741/2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treitel MA, Carlson M. Repression by SSN6-TUP1 is directed by MIG1, a repressor/activator protein. Genetics. 1995;92:3132–3136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassart JP, Georis I, Ostling J, Ronne H, Vandenhaute J. The MIG1 repressor from Kluyveromyces lactis: cloning, sequencing and functional analysis in Saccharomyes cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1995;371:191–194. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00909-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JR, Johnston M. Suppressors reveal two classes of glucose repression genes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1994;136:1271–1278. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.4.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu Y, Schmidt MC. Identification of cis-acting elements in the SUC2 promoter of Saccharomyces cerevisiae required for activation of transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(4):1002–1009. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Kumme J, Schüller HJ. Transcriptional activators Cat8 and Sip4 discriminate between sequence variants of the carbon source-responsive promoter element in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 2004;45(3):121–128. doi: 10.1007/s00294-003-0476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüller HJ. Transcriptional control of nonfermentative metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 2003;43:139–160. doi: 10.1007/s00294-003-0381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AB. Pennings pp. Tup1–Ssn6 and Swi-Snf remodelling activities influence long-range chromatin organization upstream of the yeast SUC2 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(16):5520–5531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther K, Schüller HJ. Adr1 and Cat8 synergistically activate the glucose-regulated alcohol dehydrogenase gene ADH2 of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology. 2001;147:2037–2044. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai MT, Liu DYT, Hseu TH. Cell growth restoration and high level protein expression by the promoter of hexose transporter, HXT7, from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Lett. 2007;29(8):1287–1292. doi: 10.1007/s10529-007-9397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauf J, Zimmermann FK, Müller S. Simultaneous genomic overexpression of seven glycolytic enzymes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2000;26:688–698. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(00)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz A, Serrano R, Arino J. Direct regulation of genes involved in glucose utilization by the calcium/calcineurin pathway. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(20):13923–13933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH. DNA-binding properties of the yeast Rgt1 repressor. Biochimie. 2009;91(2):300–303. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan S, Johnston M. Two different repressors collaborate to restrict expression of the yeast glucose transporter genes HXT2 and HXT4 to low levels of glucose. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(10):5536–5545. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weirich J, Goffrinil P, Kuger P, Ferrero I, Breunig KD. Influence of mutations in hexose-transporter genes on glucose repression in Kluyveromyces lactis. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:248–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Chaturvedi V, Shen SH. Identification and phylogenetic analysis of a glucose transporter gene family from the human pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. J Mol Evol. 2002;55(3):336–346. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojunga N, Entian K. Cat8p, the activator of gluconeogenic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, regulates carbon source-dependent expression of NADP-dependent cytosolic isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idp2p) and lactate permease (Jen1p) Mol Gen Genet. 1999;262:869–875. doi: 10.1007/s004380051152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartner FS, Ruth C, Langenegger D, Johnson SN, Hyka P, Lin-Cereghino GP, Lin-Cereghino J, Kovar K, Cregg JM, Glieder A. Promoter library designed for fine-tuned gene expression in Pichia pastoris. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(12):e76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gödecke S, Eckart M, Janowicz ZA, Hollenberg CP. Identification of sequences responsible for transcriptional regulation of the strongly expressed methanol oxidase-encoding gene in Hansenula polymorpha. Gene. 1994;139:35–42. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90520-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero P, Flores L, Cera T, Moreno F. Functional characterization of transcriptional regulatory elements in the upstream region of the yeast GLK1 gene. Biochem J. 1999;343:319–325. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3430319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Cera T, Herrero P, Moreno F. The hexokinase 2 protein regulates the expression of the GLK1, HXK1 and HXK2 genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem J. 2001;355:625–631. doi: 10.1042/bj3550625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardi E, Gambini A, Bellu AR. ALG2, the Hansenula polymorpha isocitrate lyase gene. Yeast. 2003;20(9):803–811. doi: 10.1002/yea.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante JJ, Law GL, Wang IT, Chang HWE, Young ET. Activator-independent transcription of Snf1-dependent genes in mutants lacking histone tails. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80(2):407–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierfelder S, Ostermann K, Göbel A, Rödel G. Vectors for glucose-dependent protein expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Biochem Biotech. 2011;163(8):954–964. doi: 10.1007/s12010-010-9099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prielhofer R, Maurer M, Klein J, Wenger J, Kiziak C, Gasser B, Mattanovich D. Induction without methanol: novel regulated promoters enable high-level expression in Pichia pastoris. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diderich JA, Schepper M, van Hoek P, Luttik MA, van Dijken JP, Pronk JT, Klaassen P, Boelens HF, de Mattos MJ, van Dam K. et al. Glucose uptake kinetics and transcription of HXT genes in chemostat cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(22):15350–15359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick KM, Spielewoy N, Kalashnikova TI, Guaderrama M, Zhu Q, Chang HC, Wittenberg C. Grr1-dependent inactivation of Mth1 mediates glucose-induced dissociation of Rgt1 from HXT gene promoters. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3230–3241. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-03-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greatrix BW, Vuuren HJJ. Expression of the HXT13, HXT15 and HXT17 genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and stabilization of the HXT1 gene transcript by sugar-induced osmotic stress. Curr Genet. 2006;49(4):205–217. doi: 10.1007/s00294-005-0046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partow S, Siewers V, Bjørn S, Nielsen J, Maury J. Characterization of different promoters for designing a new expression vector in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2010;27(11):955–964. doi: 10.1002/yea.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez RG, Hahn-Hagerdal B, Gorwa-Grauslund MF. PGM2 overexpression improves anaerobic galactose fermentation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb Cell Fact. 2010;9:40–47. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalcinati G, Knuf C, Partow S, Chen Y, Maury J, Schalk M, Daviet L, Nielsen J, Siewers V. Dynamic control of gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae engineered for the production of plant sesquitepene α-santalene in a fed-batch mode. Metab Eng. 2012;14(2):91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leandro MJ, Fonseca C, Goncalves P. Hexose and pentose transport in ascomycetous yeasts: an overview. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009;9(4):511–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Li WH. Expansion of hexose transporter genes was associated with the evolution of aerobic fermentation in yeasts. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(1):131–142. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkowski C, Krampe S, Weirich J, Hasse V, Boles E, Breunig KD. Feedback regulation of glucose transporter gene transcription in Kluyveromyces lactis by glucose uptake. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(18):5223–5229. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.18.5223-5229.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiland S, Radovanovic N, Fer MH, Winderickx J, Lichtenberg AH. Multiple Hexose Transporters of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(8):2153–2162. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.8.2153-2162.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özcan S, Vallier LG, Flick JS, Carlson M, Johnston M. Expression of the SUC2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is induced by low levels of glucose. Yeast. 1997;13:127–137. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199702)13:2<127::AID-YEA68>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutfiyya LL, Johnston M. Two zinc-finger-containing repressors are responsible for glucose repression of SUC2 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(9):4790–4797. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belinchon MM, Gancedo JM. Different signalling pathways mediate glucose induction of SUC2, HXT1 and pyruvate decarboxylase in yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007;7(1):40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Xia Z, Zhao B, Cen P. Enhancement of production of cloned α-amylase by lactic acid feeding from recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a SUC2 promoter. Biotechnol Lett. 2001;23:259–262. doi: 10.1023/A:1005641926474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iacovoni JS, Russell P, Gaits F. A new inducible protein expression system in fission yeast based on the glucose-repressed inv1 promoter. Gene. 1999;232:53–58. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00116-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergkamp RJ, Bootsman TC, Toschka HY, Mooren AT, Kox L, Verbakel JM, Geerse R, Planta RJ. Expression of an alpha-galactosidase gene under control of the homologous inulinase promoter in Kluyveromyces marxianus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;40:309–317. doi: 10.1007/BF00170386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HE, Qin R, Chae KS. Increased production of exoinulinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by expressing the Kluyveromyces marxianus INU1 gene under the control of the INU1 promoter. J Microbiol Biotechn. 2005;15(2):447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha SN, Abrahão-Neto J, Cerdán ME, González-Siso MI, Gombert AK. Heterologous expression of glucose oxidase in the yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus. Microb Cell Fact. 2010;9:4–15. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers P, Issaka A, Palecek SP. Saccharomyces cerevisiae JEN1 promoter activity is inversely related to concentration of repressing sugar. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(1):8–17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.8-17.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana C, Yoo JY, Tagne JB, Kacherovsky N, Lee TI, Young ET. Combined global localization analysis and transcriptome data identify genes that are directly coregulated by Adr1 and Cat8. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(6):2138–2146. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2138-2146.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniak A, Xue Z, Macool D, Kim JH, Johnston M. Regulatory network connecting two glucose signal transduction pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eucaryotic Cell. 2004;3(1):221–231. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.1.221-231.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade R, Kötter P, Entian KD, Casal M. Multiple transcripts regulate glucose-triggered mRNA decay of the lactate transporter JEN1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2005;332:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badziong W, Habermann P, Möller J, Aretz W. Process for using the yeast ADH2 promoter system for the production of heterologous proteins in high yield (US5866371) US Patent Office. 2012. pp. 1–16.

- Donoviel MS, Young ET. Isolation and identification of genes activating UAS2-dependent ADH2 expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;143:1137–1148. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.3.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen MWY, Fang F, Sandmeyer S, Da Silva NA. Development and characterization of a vector set with regulated promoters for systematic metabolic engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2012;29(12):495–503. doi: 10.1002/yea.2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell PR, Hall B. The primary structure of the alcohol dehydrogenase gene from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Biol Chem. 1983;258(1):143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien LJ, Lee CK. Expression of bacterial hemoglobin in the yeast, Pichia pastoris, with a low O2-induced promoter. Biotechnol Lett. 2005;27(19):1491–1497. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-1324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana-Castro R, Ramirez-Suero M, Moreno-Sanz F, Ramirez-Lepe M. Expression of the cry11A gene of Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. israelensis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Can J Microbiol. 2005;51:165–170. doi: 10.1139/w04-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Flores R, Richardson T, Bisson LF. Expression of bovine & casein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and characterization of the protein produced in vivo. J Agr Food Chem. 1990;38:1134–1141. doi: 10.1021/jf00094a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M. A model fungal gene regulatory mechanism: the GAL genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51(4):458–476. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.4.458-476.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehlin JO, Carlberg M, Ronne H. Control of yeast GAL genes by MIG1 repressor: a transcriptional cascade in the glucose response. EMBO J. 1991;10(11):3373–3377. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardocki ME, Lopes JM. Expression of the yeast PIS1 gene requires multiple regulatory elements including a Rox1p binding site. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(40):38646–38652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardo JM, Bhairi SM, Dickson RC. Identification of upstream activator sequences that regulate induction of the 3-Galactosidase gene in Kluyveromyces lactis. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7(12):4369–4376. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.12.4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanoni M, Sollitti P, Goldenthal M, Marmur J. Structure and regulation of the multigene family controlling maltose fermentation in budding yeast. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1989;37:281–322. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]