Abstract

Background

In normal prostate epithelium the TMPRSS2 gene encoding a type II serine protease is directly regulated by male hormones through the androgen receptor. In prostate cancer ERG protooncogene frequently gains hormonal control by seizing gene regulatory elements of TMPRSS2 through genomic fusion events. Although, the androgenic activation of TMPRSS2 gene has been established, little is known about other elements that may interact with TMPRSS2 promoter sequences to modulate ERG expression in TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion context.

Methods

Comparative genomic analyses of the TMPRSS2 promoter upstream sequences and pathway analyses were performed by the Genomatix Software. NKX3.1 and ERG genes expressions were evaluated by immunoblot or by quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) assays in response to siRNA knockdown or heterologous expression. QRT-PCR assay was used for monitoring the gene expression levels of NKX3.1-regulated genes. Transcriptional regulatory function of NKX3.1 was assessed by luciferase assay. Recruitment of NKX3.1 to its cognate elements was monitored by Chromatin Immunoprecipitation assay.

Results

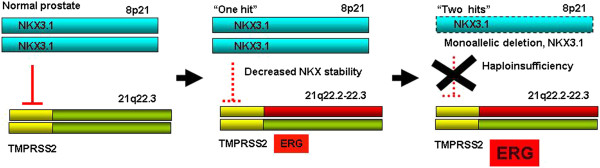

Comparative analysis of the TMPRSS2 promoter upstream sequences among different species revealed the conservation of binding sites for the androgen inducible NKX3.1 tumor suppressor. Defects of NKX3.1, such as, allelic loss, haploinsufficiency, attenuated expression or decreased protein stability represent established pathways in prostate tumorigenesis. We found that NKX3.1 directly binds to TMPRSS2 upstream sequences and negatively regulates the expression of the ERG protooncogene through the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion.

Conclusions

These observations imply that the frequently noted loss-of-function of NKX3.1 cooperates with the activation of TMPRSS2-ERG fusions in prostate tumorigenesis.

Keywords: Tumor suppressor, NKX3.1, Prostate, ERG, NFкB, Oncogene

Background

Activation of the ERG oncogene [1] represents an early event in pre-neoplastic to neoplastic transition during prostate tumorigenesis [2-4]. Rearrangements between the androgen regulated TMPRSS2 gene promoter and the ETS-related ERG gene result in TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcripts that have been found in approximately half of prostate cancer cases in the Western world [5]. Fusion of other androgen regulated genes, such as, the prostein coding SLC45A3, prostate specific antigen homologue kallikrein 2 (KLK2) or the N-MYC downstream regulated gene 1 (NDRG1) contribute to ERG activation with lower frequencies [6]. At protein levels ERG is detected as a nearly uniformly overexpressed protein in over 60% of prostate cancer patients as revealed by the diagnostic evaluation of ERG oncoprotein detection in prostatic carcinoma [7,8].

Much has been learned about the androgenic regulation of TMPRSS2 promoter [9-13] in prostate cancer. In contrast, other control elements of the TMPRSS2 promoter are largely unexplored both in the wild type, as well as, in the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion genomic context. In the current study comparative analysis of TMPRSS2 promoter upstream elements among different species revealed the presence of a conserved NKX3.1 binding site.

NKX3.1 is a bona fide tumor suppressor gene with prostate-restricted expression [14]. Loss or decreases in NKX3.1 levels has been frequently observed in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and at the pre-neoplastic to neoplastic transformation stages of prostate cancer [15,16]. Loss of Nkx3.1 cooperates with loss of Pten in engineered mouse models of prostate tumorigenesis [17,18]. Furthermore, Nkx3.1 defects cooperate with Pten-Akt pathways [19] and disrupt cellular response to DNA damage [20]. Nkx3.1 was also shown to oppose the transcription regulatory function of C-Myc [21] in mouse models. In prostate cancer cells C-MYC is activated by ERG[22-24]. A recent study has shown that ERG is a repressor of NKX3.1 raising the possibility of a feed-forward circuit in prostate tumorigenesis [25]. Our observation of conserved NKX3.1 binding elements in the TMPRSS2 promoter prompted us to examine the hypothesis that NKX3.1 is a repressor of ERG in the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion genomic context in prostate cancer.

Results

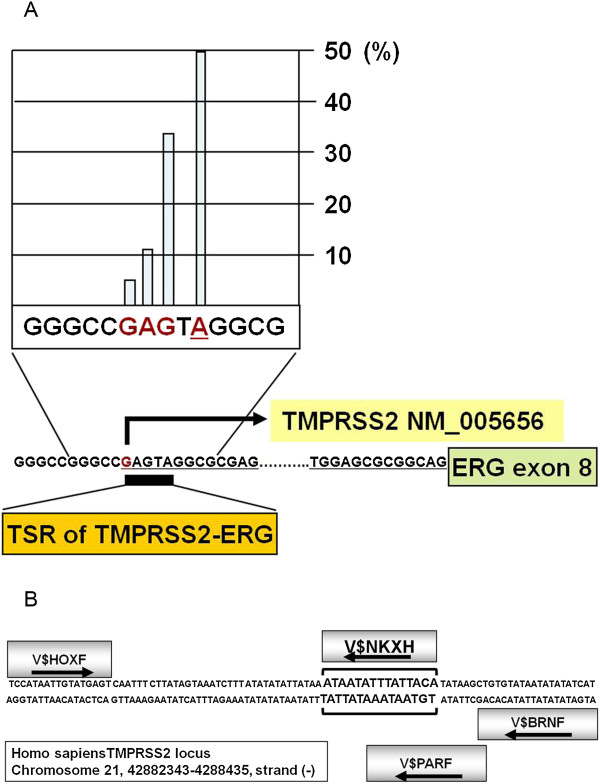

Identification of an NKX3.1 binding site within the TMPRSS2 gene promoter upstream sequences

Within the TMPRSS2 gene locus promoter downstream sequences beyond the +78 position of the first non-coding exon (NM_005656) frequently participate in genomic rearrangement events. These genomic rearrangements are characterized by the recurrent TMPRSS2 (first non-coding exon:+78) [26] to ERG (exon 8 or Exon 9) [1,27,28] fusion junctions also known as fusion type “A” or “C”, respectively [11]. In this gene fusion event the TMPRSS2 promoter-proximal and promoter upstream sequences are retained. Towards the bioinformatic analysis of TMPRSS2-ERG regulatory elements we mapped the transcription start sites (TSS) of TMPRSS2 gene in TMPRSS2-ERG fusion harboring human prostate tumors. From a carefully characterized RNA pool of ERG expressing and TMPRSS2-ERG fusion harboring prostate tumors obtained from six radical prostatectomy specimens [29], cDNA molecules were generated and amplified using 5’ cap-specific forward primers and ERG-specific reverse primers. Amplicons were isolated and cloned. Individual clones (n = 20) were analyzed by DNA sequencing and the frequency of cap-tags were plotted on the transcription start region (TSR_200587) of the TMPRSS2 gene (Figure 1A). The DNA sequence analysis revealed that the most frequent (50%) transcription start of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcripts is at +5, relative to the wild type TMPRSS2 promoter +1 position. By confirming the TSS position we focused our investigation on the +78 to15,000 upstream regulatory region of the TMPRSS2 gene on chromosome 21 (NCBI build 36.3) for further analyses. This genomic region encompasses upstream regulatory elements (-13.5 kb) shown to control cancer-associated expression of the ERG oncogene [30].

Figure 1.

Defining a conserved composite model for NKX3.1 binding within the TMPRSS2 gene promoter upstream sequences. (A) Frequency of TMPRSS2-ERG transcript initiation sites within the TMPRSS2 promoter transcriptional start region (TSR). (B) NKX3.1 model match within the human TMPRSS2 promoter upstream region with conserved distance, positions and orientations (arrows) of transcription factor binding sites.

Comparative analysis of modular regulatory sequences of various species is a powerful approach for pinpointing functionally relevant regulatory elements [31-33]. We applied a computational approach (FrameWoker software, release 5.4.3.3) that has been shown to identify conserved orientation, relative position and relative distance of binding motif (matrix) clusters [34,35] also known as the “motif grammar” [36] using the Matrix Family Library Version 7.1. We have examined the -15,000;+78 bp regions of human, rhesus monkey, rat and mouse TMPRSS2 gene promoter upstream sequences for the conservation of composite regulatory elements. Striking conservation of a composite model was noted in this analysis that was mapped to the human TMPRSS2 -2350; -2258 sequences relative to the TSS. Within the composite model we have identified the vertebrate NKX3.1 matrix (V$NKXH) as the prostate-specific component of the model and putative binding site was termed as NKX3.1 binding site 1 (NBS1) (Figure 1B).

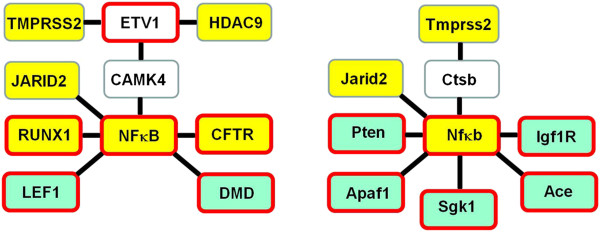

NFкB-centered network of NKX3.1 target gene signatures

Utilizing this highly conserved model the entire human genome was searched for model matches (ModelInspector Release 5.6) to define gene loci potentially targeted by NKX3.1. After filtering for non-redundant, intronic, exonic and promoter model matches within gene loci of annotated genes, knowledge-based pathway analysis was performed using functional co-citation settings. The analysis revealed a network with NFкB in the central regulatory node (Additional file 1: Figure S1). As expected, searching of the entire human genome for this composite model precisely identified the TMPRSS2 gene upstream -2350; -2258 sequences. In contrast, search of the dog, bovine, opossum and zebra fish genome failed to identify model matches within the Tmprss2 loci of these species. In a meta-analysis approach we compared the comparative genome analysis-derived network to the signature of Nkx3.1-targeted genes defined by in vivo ChIP assay in a mouse model (Additional file 1: Figure S2) [21]. Strikingly similar NFкB-centered regulatory network was revealed by the analysis (Figure 2). NKX3.1 target genes within the compared datasets were enriched in functionally related genes. Moreover, the analysis highlighted orthologues of TMPRSS2, JARID2 and the NFкB genes. The apparent similarity between these datasets has prompted us to examine the disease association of NKX3.1 target genes by gene ontology analyses. Enrichment of chromosome aberrations, inversion, breakage and associated diseases was revealed by the analysis (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Summary of NFкB centered NKX3.1 target gene signatures from in silico (left panel) and from the meta-analysis of in vivo data (right panel). Experimentally validated human genes and their orthologues in mouse are highlighted in yellow. Secondary nodes representing genes with four or more functional connections are stemming from the central regulatory node (green boxes). Nodes with four or more functional connections are outlined by red. Connected genes are marked with white background color.

Table 1.

Disease association analysis of predicted NKX3.1 targeted genes within the human genome reveals the enrichment of chromosome aberrations, inversion, breakage gene ontology categories

|

MeSH Disease/input n = 464 |

|

Genes |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | Expected | Observed | |

| Chromosome inversion |

1.67e-04 |

120 |

152 |

| Chromosome aberration |

2.06e-04 |

13 |

27 |

| Angelman Syndrome |

2.99e-04 |

3 |

10 |

| Chromosome breakage |

3.45e-04 |

20 |

36 |

| Uniparental disomy |

3.95e-04 |

4 |

12 |

| Prader-Willi Syndrome |

8.64e-04 |

5 |

13 |

| Translocation, genetic | 9.83e-04 | 59 | 82 |

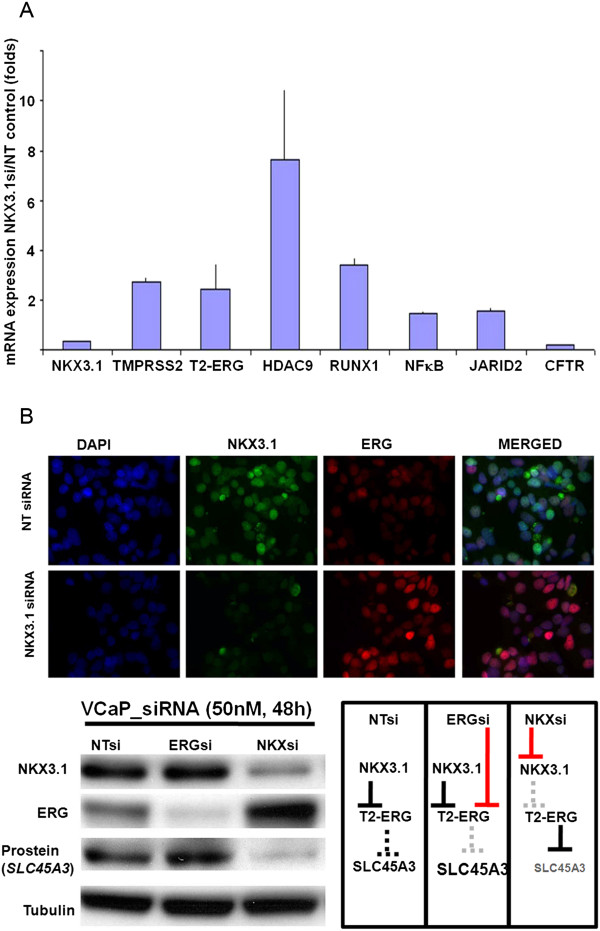

Altered expression of predicted downstream target genes in response to NKX3.1 depletion

To evaluate NKX3.1 in TMPRSS2-ERG fusion harboring prostate cancer cells we utilized the siRNA depletion strategy. Consistent with a negative regulatory function of NKX3.1, the transcripts of endogenous TMPRSS2-ERG fusion allele, as well as, the wild type TMPRSS2 showed elevated expression along with HDAC9, RUNX1, NFкB and JARID2 genes in response to NKX3.1 inhibition (Figure 3A). In line with previous reports we also noted the reduction of CFTR expression in response NKX3.1si. This finding suggests that CFTR expression in the human prostate may indeed positively regulated by NKX3.1[37]. Gene expression response to NKX3.1 knockdown was noted in approximately half of the examined NKX3.1 target genes. Whole genomic search for model matches in human, rhesus monkey, rat and mouse TMPRSS2 promoter upstream sequences precisely identified matches of the NKX3.1 model. Thus NKX3.1 as a negative regulator of TMPRSS2 may evolve in this lineage, since, we found no evidence of model matches within Tmprss2 promoter upstream regions of zebra fish, opossum, dog and cow genomes. Despite of known informatics constrains, such as, model overfitting and limitations in the employed functional assays the results suggest that comparative analyses for defining conserved repressor elements is a valid approach providing efficient guidance for the experimental validation.

Figure 3.

Expression of predicted NKX3.1 target genes in response to NKX3.1 inhibition. (A) Depletion of NKX3.1 results in increases in mRNA levels of wild type TMPRSS2, TMPRSS2-ERG fusion (T2-ERG), HDAC9, RUNX1, NFкB and JARID. In contrast, robust reduction of CFTR levels is apparent in response to NKX3.1 inhibition. (B) Rescue of ERG and its downstream function by NKX3.1 inhibition (NKX3.1 siRNA) is shown by nuclear localization of ERG (upper panel), sharp increases in ERG protein levels (lower panel), and by the depletion of the ERG-downstream target prostein (SLC45A3). Schematic depiction of the negative regulatory role of NKX3.1 in the context of TMPRSS2-ERG (T2-ERG) gene fusion (inset).

To assess the function of NKX3.1 in regulating the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion gene we evaluated ERG expression in response to specific inhibition of NKX3.1. Knockdown NKX3.1 with siRNA resulted in elevated ERG protein levels (Figure 3B). Increased expression and nuclear localization of ERG oncoprotein in response to NKX3.1 siRNA further supported the repressor role of NKX3.1. Consistent with elevated ERG levels we observed marked decreases in prostein. This prostate differentiation associated protein is encoded by the SLC45A3 gene that is negatively regulated by ERG [22].

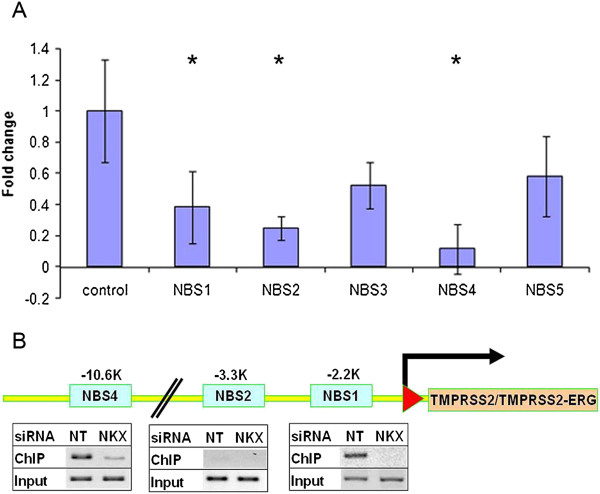

NKX3.1 is a repressor of the TMPRSS2 gene

Although, NBS1 is the only evolutionarily conserved NKX3.1 binding site prediction within the TMPRSS2 promoter upstream region, transcription factor binding site model match search by MatInspector identified further stand-alone NKX3.1 binding sites. The single matrix prediction identified a tight cluster of five single NKX3.1 matrix model matches (V$NKX31.01) between positions -2298 and -2168 relative to the transcription initiation site that showed partial overlap with NBS1. Further upstream clusters of single NKX3.1 model matches were identified and were designated as NBS2 (-3292; -3277), NBS3 (-8019; -7902), NBS4 (-10684; -10615), and NBS5 (-14628; - 14614). For the assessment of transcription regulatory functions, NBS1-5 sites were cloned upstream to a Luciferase reporter vector. The assay result indicated negative regulatory functions for NBS1, NBS2 and NBS4 sequences (Figure 4A). To evaluate the endogenous TMPRSS2-ERG gene expression response to NKX3.1 inhibition, VCaP cells were grown in hormone depleted media for three days. Cells were transfected by NKX3.1 siRNA or by non-targeting control siRNA molecules. Synthetic androgen (R1881) was added to the media to induce the expression of androgen regulated genes, including NKX3.1 and TMPRSS2-ERG. After 24 h induction cells were processed for Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay examining the recruitment of NKX3.1 to NBS1, NBS2 and NBS4. NBS amplicons were excised from the gel and were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The experiment confirmed the recruitment of NKX3.1 to NBS1 and NBS4 regions (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Predicted NKX3.1 binding sequences of the TMPRSS2 promoter are portable repressor elements. (A) The transcriptional regulatory function of predicted NKX3.1 binding sites (NBS1-5) was assessed by luciferase reporter systems. Relative luciferase units are shown as fold changes relative to the control expression levels. Significant (P < 0.05) reduction of reporter gene expression are marked by asterics (B) Specific recruitment of endogenous NKX3.1 to predicted NBS1 and NBS4 binding sites of the TMPRSS2 promoter upstream regions was assessed by in vivo ChIP assay in the absence (NT) or presence of NKX3.1 siRNA (NKX).

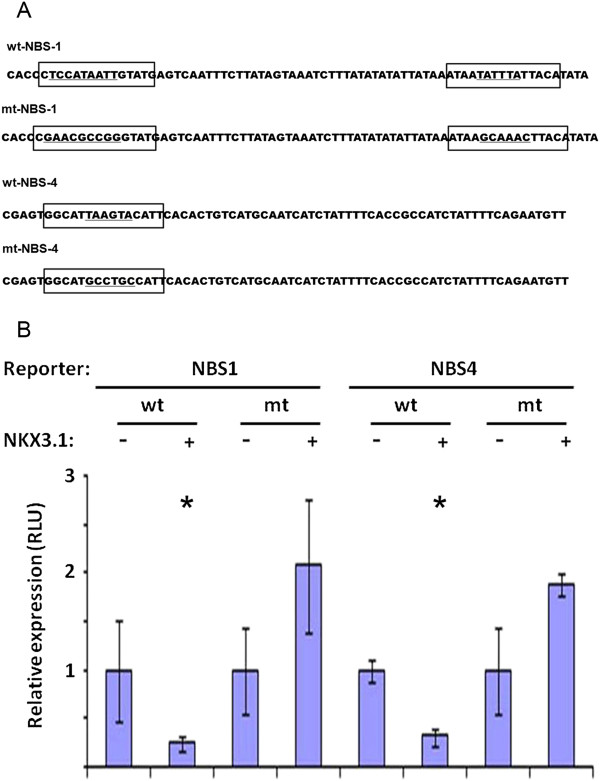

Although ChIP assays provided an estimated region of recruitment within the chromatin context of NBS1 and NBS4 it does not reveal the actual position and specificity of transcriptional regulatory elements. To address the specificity of NBS1 and NBS4 core binding sites we have introduced transversion point mutations to the core cognate elements aiming to disrupt the NKX3.1 homeodomain DNA recognition (Figure 5A). To reduce the possibility of generating of de novo TF binding sites we have used the SeqenceShaper program (http://www.genomatix.de). Wild type and corresponding mutant NBS1 and NBS4 harboring reporter vectors were assayed for reporter gene activity by transfecting HEK293 cells in the presence of NKX3.1 expressing pcDNA-NKX3.1-HA expression vector or control pcDNA. The transfection efficiency was monitored by co-transfecting phRGB-TK Renilla-Luc control vector. In the presence of heterologously expressed NKX3.1 the expression of wtNBS1 and wtNBS4 reporters were reduced 4–3 folds, respectively. NBS1- and NBS4-mediated transcriptional repression was disrupted by specific mutations within the V$NKXH core recognition sequences, accompanied by a modest activation in reporter expressions (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Both NKX3.1 protein and wild type NKX3.1 binding sites are required for the transcriptional repressor function of TMPRSS2 promoter upstream sequences. (A) Schematic representation of NBS1 and NBS4 sequences marking predicted NKX3.1 binding elements in brackets. Core recognition sequences with transversion mutations are underlined in the wild type (wt) and in the mutant (mt) sequences. (B) Relative luciferase units (RLU) of wild type and mutant NKX3.1 binding sites were assayed in reporter constructs in the presence (+) of heterologously expressed NKX3.1 or in the presence of control vector (-). Asterisk symbols mark significant (P < 0.05) reductions in reporter gene expression.

Discussion

Comparative assessment of evolutionary conserved cognate sequences within the TMPRSS2 promoter upstream sequences revealed strong conservation of an NKX3.1 binding site. Experimental evaluation of the predicted composite element suggested that this element confers NKX3.1-mediated repression to the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion gene in prostate cancer cells. Inhibition of NKX3.1 resulted in elevated expression and nuclear localization of ERG and resulted in reduced levels of the ERG-downstream regulated prostein encoded by the SLC45A3 gene. Assays for the transcription regulatory function of NKX3.1 binding sites indicated repressor function that was disrupted by specific mutations affecting the DNA recognition of NKX3.1 transcription factor. Recruitment of endogenous NKX3.1 to the evolutionarily conserved cognate element was confirmed by in vivo ChIP assay.

Loss of NKX3.1, contributes to the cancer associated function of AR [38,39], C-MYC [21], p53, PTEN [40], Topoisomerase I [41] and TWIST1 [42] in prostate cancer. ERG oncogene, a result of the TMPRSS2-ERG fusions, negatively regulates NKX3.1 through EZH2 [25]. In the current study we have examined evolutionary conserved composite regulatory models of the TMPRSS2 gene. The analysis revealed a remarkable conservation of a composite model with an NKX3.1 binding site in the lineage of mouse, rat, rhesus monkey and human species members of the Euarchontoglires (Supraprimates) super ordo. This composite model identified sequences within intronic regions of the human genome. Increased expression of evaluated NKX3.1 target genes (HDAC9, RUNX1, TMPRSS2, TMPRSS2-ERG, NFкB and JARID2) was observed in response to NKX3.1 inhibition. Meta-analysis of Nkx3.1 target genes from in vivo ChIP assay of mouse prostates indicated that upstream regulatory regions are indeed enriched in core elements, such as, V$NKXH, V$HOXF and V$BRNF (Table S3 in [21]) similar to the model we have obtained from in silico analysis. Pathway analysis of NKX3.1 target genes from the current study, as well as, from the reported in vivo model [21] revealed NFкB as the central regulatory node of NKX3.1 target gene signatures. Furthermore, the analyses indicated, robust enrichment of genes controlling chromosomal integrity. These findings are consistent with the reported role of NKX3.1 in cellular response to DNA damage [20,41]. These observations are also consistent with an NFкB-mediated protective function of NKX3.1 linked to inflammation and tumorigenesis [15,43-47]. Taken together our study highlights NKX3.1 as a negative regulator of theTMPRSS2 promoter. Thus, the frequently observed haploinsufficiency of NKX3.1 in prostate cancer may significantly contribute to the activation of ERG protooncogene in the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion genomic context. This finding highlights the integrated role of TMPRSS2-ERG gain and NKX3.1 losses as cooperating events in prostate tumorigenesis (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

NKX3.1 haploinsufficiency results in the loss of negative control over the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion.

Conclusions

Approximately half of the prostate cancer cases harbor the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions in Western countries. This recurrent oncogenic event leads to the activation of the ERG oncogene. In the current study evaluation of conserved regulatory elements of TMPRSS2 promoter upstream sequences revealed conservation of binding sites for the NKX3.1 tumor suppressor. NKX3.1 binds to these sequences and represses the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion gene. Thus, the frequently observed loss of NKX3.1 in prostate cancer may significantly contribute to the activation of ERG protooncogene. Pathway analysis of NKX3.1 target genes from the current study, as well as, from the reported in vivo studies revealed NFкB as the central regulatory node of NKX3.1 target gene signatures with robust enrichment in genes controlling chromosomal integrity. These findings suggest that TMPRSS2-ERG gain and NKX3.1 losses are potentially cooperating genetic events in prostate tumorigenesis.

Methods

Cell lines, cell culture and reagents

Human prostate tumor cell line, VCaP and human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD) and were maintained in growth medium and under conditions recommended by the supplier. The synthetic analogue of androgen, R1881, was purchased from New England Nuclear (Boston, MA).

Inhibition of NKX3.1 and ERG with small interfering RNA and heterologous expression of NKX3.1

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) oligo duplexes against human NKX3.1(L-015422-00), and Non-targeting control siRNA (D-001206-13-20) were from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO), ERGsi RNA as previously described [22]. Transfection or co-transfection of 50 nM siRNAs and 1 μM of plasmids was carried out with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in triplicates. The wild type human NKX3.1 expressing vector pcDNA3.1-NKX3.1-HA was a kind gift from Dr. Charles J. Bieberich, University of Maryland Baltimore County, Baltimore, Maryland. In six-well plates HEK293 cells were transfected in triplicates with the pcDNA3.1 control or with the pcDNA3.1-NKX3.1-HA expression vectors by using Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were harvested for protein and mRNA analysis after 48 h incubation.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

For assessing the specific recruitment of endogenous NKX3.1 to the predicted NKX3.1 binding sites in vivo ChIP assays were carried out in the presence of NKX3.1 siRNA or control NT siRNA [35]. VCaP cells were grown in 10% charcoal stripped serum (cFBS) containing media (Gemini Bio-Products, Carlsbad, CA) for 48 h and were transfected with 50 nM NKX3.1 siRNA or 50 nM of NT control. Cells were incubated for 24 h followed by the addition of 0.1 nM of R1881. At the 48 h time point following hormone induction formaldehyde was added to the cell culture media to 1% and the cells were processed for ChIP assay [48] by using the mouse monoclonal anti-ERG antibody (CPDR ERG-MAb, clone 9FY, currently available from Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) [7]. NBS1 region from input and ChIP DNA samples were amplified by the forward 5’-TGTTTCTCTGGAGAACCCTGA-3’ and reverse 5’- GCAGGTGCAGTTGTCTTTCA-3’; NBS2 region was amplified by the forward 5’- CAATCCAGGCAGGGCTATTA and reverse 5’- GGGCAATAGCTGGTGTTTGT-3’; the NBS4 region was amplified by the 5’- TCATCTATTTTCACCGCCATC-3’ and 5’- ACACGCACACACCACATCAT-3’ primer pairs under previously described PCR conditions [22,35].

Assessment of the transcription initiation site of TMPRSS2-ERG transcript by 5’ oligocapping

Under approved protocol from the WRAMC IRB six cases were identified with TMPRSS2-ERG fusion harboring prostate tumors. Total RNA was isolated from the tumors and were pooled [29]. From the pool 4.2 μg of total mRNA was subjected to 5’ oligocapping procedure (FirstChoice, RLM-RACE, Ambion, Austin, TX) pairing the 5’-GGCGTTGTAGCTGGGGGTGAG-3’ [11] with the outer, and 5’- CAATGAATTCGTCTGTACTCCATAGCGTAGGA-3’ with the inner primer. Amplicons were gelpurified and cloned into pUC19 vector and were subjected to DNA sequencing in forward and reverse directions.

Comparative analysis of the TMPRSS2 gene promoter upstream sequences

DNA sequences of the 15,000; +78 bp region of Homo sapiens, Macaca mulatta, Rattus norvegicus and Mus musculus genomes were extracted from the NCBI build 36.3 database. Scanning from the proximal promoter towards the distal sequences 3,000 bp homologue segments were evaluated allowing 500 bp overlap of segments at each composite model scanning step. DNA sequence segments of all examined species were analyzed by the FrameWorker (version 5.4.3.3, http://www.genomatix.de) for conserved composite model matches by using the Matrix Family Library 7.1 at the following settings: core promoter elements 0.75/optimized, vertebrates (0.75/optimized); distance between adjacent elements: 5–200; distance band with: 10, exhaustive model search with minimum number of elements = 2 and max number of elements = 6. Overall the highest number of common single element match was the V$NKXH, a binding site for NKX3.1. Ranking the composite models revealed only one model that reached the maximum (four element) complexity. The top scoring model was defined as V$HOXF (strand orientation (+), distance to next element 43-51 bp), V$NKXH (strand orientation (-), distance to next element 7-14 bp), V$PARF (strand orientation (-), distance to next element 17-23 bp); V$BRNF (strand orientation (-), distance to next element 0 bp) at settings of minimum core similarity = 0.75 and minimum matrix similarity “optimized”. Next the entire human genome (NCBI build 36.3) was searched with this composite model for matches by the ModelInspector 5.6 program (http://www.genomatix.de). Whole –genomes model searches confirmed the model match within the TMPRSS2 gene promoter upstream sequences in Homo sapiens, Macaca mulatta, Rattus norvegicus and Mus musculus genomes and indicated the absence of model match within the Tmprss2 gene loci of Canis lupus familiaris, Bos Taurus, Monodelphis domestica, and Danio rerio.

Pathway and meta-analyses of NKX3.1 genomic targets

Predicted gene targets for NKX3.1 were obtained by in silico composite model match analysis of the entire human genome. Among the total 1636 (1371 non-redundant) model matches 559 were non-annotated. Within the annotated 1037 model matches (Additional file 2: Table S1) 627 was found in intronic, 10 and 12 matches were found in exonic or promoter sequences, respectively. Intronic, exonic and promoter model matches were further filtered for genes with defined gene symbols and the final set of 452 genes were used as input for pathway analysis (Additional file 2: Table S2). Prostate Cancer meta-analysis dataset used in our study was based on the report of Anderson et al. [21]. NKX3.1 target genes were imported into the Genomatix Pathway System (GePS, http://www.genomatix.de). In GePS genes were mapped into networks based on the information extracted from public databases including National Cancer Institute Pathway Interaction Database (http://pid.nci.nih.gov) and Biocarta (http://www.biocarta.com). The generated network displayed as nodes and connections focused on functional relationships between genes based on the number of evidences in literature (Figures S1 and S2). For the analyses we have used function word evidence level to generate the network where gene pairs are noted if they occur in the same sentence connected with a function word.

Immunoblot assay

At the specified time points VCaP cells treated with NKX3.1si or control NTsi were lysed in M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) supplemented with protease (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). ERG proteins were detected by Western blot (NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel, Invitrogen) as described previously using immunoaffinity-purified anti- ERG mouse monoclonal antibody 9FY [7]. The anti-NKX3.1 polyclonal antibody (T-19) and anti-alpha tubulin (B-7) antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA) and the anti-prostein antibody recognizing the protein product of the SLC45A3 gene was obtained from DAKO (Carpinteria, CA). Representative images of two independent experiments are shown in the Results.

Immunofluorescence assay of siRNA treated VCaP cells

VCaP cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and centrifuged onto silanized slides (Sigma, St.Louis, MO) with a cytospin centrifuge. Cells were immunostained with anti-ERG (9FY) and anti-NKX3.1 (Santa Cruz) followed by goat anti-mouse Alexa-488 and anti-goat Alexa-594 secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Images were captured by using a 40X/0.65 N-Plan objective on a Leica DMLB upright microscope with a QImaging Retiga-EX CCD camera (Burnaby, BC, Canada) controlled by OpenLab software (Improvision, Lexington, MA). Images were converted into color and merged by using Adobe Photoshop.

NKX3.1 binding site (NBS) luciferase reporters and dual-luciferase reporter assays

Mutant NBS sequences were designed to minimize the generation of artificial binding sites by the Sequence Shaper (http://www.genomatix.de). Wild type and mutant NBS sequences were chemically synthesized adding a cohesive overhang for Nhe1 site (CGCGT) at the 5'-end of the sense strand and an overhanging Bgl2 site (TCGAG) at the 3‘ as follows: wild type NBS1 5’-CTCCATAATTGTATGAGTCAATTTCTTATAGTAAATCTTTATATATATTATAAATAATATTTATTACATATAAGCTGTGTATAATATATATCAT-3’; mutant NBS1 5’-GAACGCCGGGTATGAGTCAATTTCTTATAGTAAATCTTTATATATATTATAAATAAGCAAACTTACATATAAGCTGTGTATAATATATATCAT-3’ ; wild type NBS2 5’-CACATAACTTAAGGCATATTGACTTTATATCATTGTATTAAGTATTGTTAATTTTACATTA-3’; mutant NBS2 5’-CACATAAAGGCCTGCATATTGACTTTATATCATTGGCGGCCTTATTTGGCCGGTTACATTA-3’; wild type NBS3 5’-CGAGAAAAGGATTCAAATACTTAGGAAGATTGAAATGTGAGGGT-3’; mutant NBS3 5’-CGAGAAAAGGATTCAAAGCCGGCGGAAGATTGAAATGTGAGGGT-3’; wild type NBS4 5’- CGAGTGGCATTAAGTACATTCACACTGTCATGCAATCATCTATTTTCACCGCCATCTATTTTCAGAATGTTCTCA-3’; mutant NBS4 5’- CGAGTGGCATGCCTGCCATTCACACTGTCATGCAATCATCTATTTTCACCGCCATCTATTTTCAGAATGTTCTCA-3’; wild type NBS5 5’-CAAAACCAAATACTGCATGTTCTCACTTATAAGTGGGAGCTGGACAATGAGAACACATGGACACAGGGAGA-3’; mutant NBS5 5’-CAAAACCAAATACTGCATGTTCTAACAGGCTACTGTGGAGCTGGACAATGAGAACACATGGACACAGGGAGA-3’. The 5’ end of synthetic oligonucleotides were phosphorylated by using polynucleotide kinase, the complementary strands were annealed and gelpurified and ligated to the NheI-BglII sites of the gelpurified, phRG-TK reporter (Promega, Madison, WI). The phRG-TK vector is a synthetic reporter vector that has been designed to minimize binding sites for transcription factors. HEK293 cells were transfected with the reporter and pGL3 luciferase control vectors in triplicates. Forty-eight hours after the transfection, the activities of control phRG-TK reporter Renilla luciferase and pGL3 Firefly luciferase constructs were determined by the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega, Madison, WI). Cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed with 1 × passive lysis buffer. Twenty μl of cell lysates were transferred into the luminometer tube containing 100 μl luciferase assay reagent II. Firefly luciferase activity (N1) and were measured first, and then Renilla luciferase activities (N2) were determined after the addition of 100 μl Stop & Glo reagent. N2/N1 light units were averaged from three measurements and were expressed as relative luciferase units (RLU).

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and real-time PCR quantification

Total RNA was extracted from cell monolayer using Trizol® total RNA isolation reagent (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Real-time PCR was performed in triplicates using an Applied Biosystems 7300 Sequence Detection system using SYBR green PCR mix (Qiagen) or by TaqMan assay (Applied Biosystems). The expression of GAPDH was simultaneously analyzed as endogenous control, and the target gene expression in each sample was normalized to GAPDH[49]. RNA samples without reverse transcription were included as the negative control in each assay. Amplification plots were evaluated and threshold cycle (CT) was set for each experiment. Measurements for target gene and GAPDH endogenous control were averaged across triplicates and standard deviation for each set was calculated. ΔCT values were calculated by subtracting averaged GAPDH CT from averaged target gene CT and expression fold-change differences were calculated by comparing ΔCT values among sample sets. Primer pairs for the amplification of target genes were as follows. HDAC9: forward 5’- CAAATGGTTTCACAGCAACG -3’, reverse 5’- TGCGTCTCACACTTCTGCTT -3’; JARID2: forward 5’- AGGAGACTGGAAGAGGCACA -3’ and reverse 5’- GTCCGTTCAGCAGACCTCTC -3’; NFкB: forward 5’- TATGTGGGACCAGCAAAGGT -3’ and reverse 5’- AAGTATACCCAGGTTTGCGAAG -3’; RUNX1 forward 5’- CAGATGGCACTCTGGTCACT-3’ and reverse 5’- TGGTCAGAGTGAAGCTTTTCC-3’; CFTR forward 5’- CCAGATTCTGAGCAGGGAGA-3’; reverse 5’- TTTCGTGTGGATGCTGTTGT-3’. Primers and probes for TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS2-ERG, as well as for NKX3.1 have been described before [50,51].

Statistical analysis

Gene expression analyses results are shown by bars representing mean+/- S.E., from three independent experiments (n = 3). Anova and Dunnett t test were applied for statistic analysis using the SAS software (http://www.sas.com). Significant gene expression differences, P < 0.05, are marked with asterisk. Enrichment scores and P-values of the bioinformatics analyses were calculated by the Genomatix Software (http://www.genomatix.de).

Abbreviations

NKX3.1: NK3 Homeobox 1; Transmembrane protease: serine 2; NBS: NKX3,1 binding site; ERG: V-Ets Erythroblastosis Virus E26 Oncogene Homolog (Avian); SLC45A3: Solute carrier family 45, member 3; JARID2: Jumonji, AT Rich Interactive Domain 2; NFкB: Nuclear Factor of Kappa Light Polypeptide Gene Enhancer In B-Cells 1; HDAC9: Histone Deacetylase 9; RUNX1: Runt-Related Transcription Factor 1; CFTR: Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (ATP-Binding CassetteSub-Family C, Member 7); TSR: Transcriptional start region; TSS: Transcriptional start site; HEK293: Human Embryonic Kidney 293 cell line; VCaP: Vertebral-Cancer of the Prostate cell line.

Competing interest

AD, S-HT and SS are coinventors of the ERG-MAb 9FY, licensed by the Biocare Medical Inc.

Authors’ contributions

AD and SS designed research. RT, FS, GP and AAM performed experiments. S-HT contributed with the new ERG-MAb reagent and critical experimental procedures. RT, SK and AD performed bioinformatics experiments. RT and AD analyzed data. AD and SS wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

NFкB forms the central node of predicted NKX3.1 target genes within the human genome.

IDs of annotated genes (1037) obtained from the list of non-redundant model matches of predicted NKX3.1 targets within the human genome. The TMPRSS2 gene ID is underlined on chromosome 21.

Contributor Information

Rajesh Thangapazham, Email: rajesh.thangapazham@usuhs.edu.

Francisco Saenz, Email: rodosaenz@gmail.com.

Shilpa Katta, Email: skatta@cpdr.org.

Ahmed A Mohamed, Email: amohamed@cpdr.org.

Shyh-Han Tan, Email: stan@cpdr.org.

Gyorgy Petrovics, Email: gpetrovics@cpdr.org.

Shiv Srivastava, Email: ssrivastava@cpdr.org.

Albert Dobi, Email: adobi@cpdr.org.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ms. Atekelt Tadese for the excellent technical assistance, to Mr. David Xu for the DNA sequence analysis and to Mr. Stephen Doyle for the art work. This research was supported by the Prostate Cancer Foundation Competitive Award Program to A.D, by the U.S. Army Prostate Cancer Research Program Grant PC073614 and National Cancer Institute R01CA162383 to S.S. During this study F.S. was supported by the U.S. Army Prostate Cancer Research HBCU Program to S.S. and to Deepak Kumar. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

References

- Reddy ES, Rao VN, Papas TS. The erg gene: a human gene related to the ets oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(17):6131–6135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahim S, Uren A. Emergence of ETS transcription factors as diagnostic tools and therapeutic targets in prostate cancer. Am J of Transl Res. 2013;5(3):254–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri CE, Bangma CH, Bjartell A, Catto JW, Culig Z, Gronberg H, Luo J. Visakorpi T. The Mutational Landscape of Prostate Cancer. European urology: Rubin MA; 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessels D, Schalken JA. Recurrent gene fusions in prostate cancer: their clinical implications and uses. Curr Urol Rep. 2013;14(3):214–222. doi: 10.1007/s11934-013-0321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar-Sinha C, Tomlins SA, Chinnaiyan AM. Recurrent gene fusions in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(7):497–511. doi: 10.1038/nrc2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin MA. ETS rearrangements in prostate cancer. Asian J of Androl. 2012;14(3):393–399. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusato B, Tan SH, Young D, Dobi A, Sun C, Mohamed AA, Thangapazham R, Chen Y, McMaster G, Sreenath T. et al. ERG oncoprotein expression in prostate cancer: clonal progression of ERG-positive tumor cells and potential for ERG-based stratification. Prostate cancer and prostatic Dis. 2010;13(3):228–237. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2010.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K, Tomlins SA, Mudaliar KM, Chiu YL, Esgueva R, Mehra R, Suleman K, Varambally S, Brenner JC, MacDonald T. et al. Antibody-based detection of ERG rearrangement-positive prostate cancer. Neoplasia. 2010;12(7):590–598. doi: 10.1593/neo.10726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Ferguson C, White JT, Wang S, Vessella R, True LD, Hood L, Nelson PS. Prostate-localized and androgen-regulated expression of the membrane-bound serine protease TMPRSS2. Cancer Res. 1999;59(17):4180–4184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agoulnik IU, Weigel NL. Coactivator selective regulation of androgen receptor activity. Steroids. 2009;74(8):669–674. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Sun XW, Varambally S, Cao X, Tchinda J, Kuefer R. et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310(5748):644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignon JC, Koopmansch B, Nolens G, Delacroix L, Waltregny D, Winkler R. Androgen receptor controls EGFR and ERBB2 gene expression at different levels in prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2009;69(7):2941–2949. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsbie DS, Xu J, Chen Y, Borsu L, Scher HI, Rosen N, Sawyers CL. Histone deacetylases are required for androgen receptor function in hormone-sensitive and castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(3):958–966. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Nandi AK, Li X, Bieberich CJ. NKX-3.1 interacts with prostate-derived Ets factor and regulates the activity of the PSA promoter. Cancer Res. 2002;62(2):338–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abate-Shen C, Shen MM, Gelmann E. Integrating differentiation and cancer: the Nkx3.1 homeobox gene in prostate organogenesis and carcinogenesis. Differ; Res in Biol diversity. 2008;76(6):717–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata T, Schultz D, Hicks J, Hubbard GK, Mutton LN, Lotan TL, Bethel C, Lotz MT, Yegnasubramanian S, Nelson WG. et al. MYC overexpression induces prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and loss of Nkx3.1 in mouse luminal epithelial cells. PloS one. 2010;5(2):e9427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Cardiff RD, Desai N, Banach-Petrosky WA, Parsons R, Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Cooperativity of Nkx3.1 and Pten loss of function in a mouse model of prostate carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(5):2884–2889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042688999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abate-Shen C, Banach-Petrosky WA, Sun X, Economides KD, Desai N, Gregg JP, Borowsky AD, Cardiff RD, Shen MM. Nkx3.1; Pten mutant mice develop invasive prostate adenocarcinoma and lymph node metastases. Cancer Res. 2003;63(14):3886–3890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H, Zhang B, Watson MA, Humphrey PA, Lim H, Milbrandt J. Loss of Nkx3.1 leads to the activation of discrete downstream target genes during prostate tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2009;28(37):3307–3319. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen C, Gelmann EP. NKX3.1 activates cellular response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 2010;70(8):3089–3097. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson PD, McKissic SA, Logan M, Roh M, Franco OE, Wang J, Doubinskaia I, van der Meer R, Hayward SW, Eischen CM. et al. Nkx3.1 and Myc crossregulate shared target genes in mouse and human prostate tumorigenesis. The J of Clin Invest. 2012;122(5):1907–1919. doi: 10.1172/JCI58540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Dobi A, Mohamed A, Li H, Thangapazham RL, Furusato B, Shaheduzzaman S, Tan SH, Vaidyanathan G, Whitman E. et al. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion, a common genomic alteration in prostate cancer activates C-MYC and abrogates prostate epithelial differentiation. Oncogene. 2008;27(40):5348–5353. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong Y, Xin L, Goldstein AS, Lawson DA, Teitell MA, Witte ON. ETS family transcription factors collaborate with alternative signaling pathways to induce carcinoma from adult murine prostate cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(30):12465–12470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905931106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JC, Xu J, Wongvipat J, Hieronymus H, Carver BS, Leung DH, Taylor BS, Sander C, Cardiff RD, Couto SS. et al. Cooperativity of TMPRSS2-ERG with PI3-kinase pathway activation in prostate oncogenesis. Nat Genet. 2009;41(5):524–526. doi: 10.1038/ng.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunderfranco P, Mello-Grand M, Cangemi R, Pellini S, Mensah A, Albertini V, Malek A, Chiorino G, Catapano CV, Carbone GM. ETS transcription factors control transcription of EZH2 and epigenetic silencing of the tumor suppressor gene Nkx3.1 in prostate cancer. PloS one. 2010;5(5):e10547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoloni-Giacobino A, Chen H, Peitsch MC, Rossier C, Antonarakis SE. Cloning of the TMPRSS2 gene, which encodes a novel serine protease with transmembrane, LDLRA, and SRCR domains and maps to 21q22.3. Genomics. 1997;44(3):309–320. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VN, Papas TS, Reddy ES. erg, a human ets-related gene on chromosome 21: alternative splicing, polyadenylation, and translation. Science. 1987;237(4815):635–639. doi: 10.1126/science.3299708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owczarek CM, Portbury KJ, Hardy MP, O'Leary DA, Kudoh J, Shibuya K, Shimizu N, Kola I, Hertzog PJ. Detailed mapping of the ERG-ETS2 interval of human chromosome 21 and comparison with the region of conserved synteny on mouse chromosome 16. Gene. 2004;324:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Dobi A, Sreenath T, Cook C, Tadase AY, Ravindranath L, Cullen J, Furusato B, Chen Y, Thangapazham RL. et al. Delineation of TMPRSS2-ERG splice variants in prostate cancer. Clin cancer Res: an Off J of the Am Assoc for Cancer Res. 2008;14(15):4719–4725. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Li W, Liu XS, Carroll JS, Janne OA, Keeton EK, Chinnaiyan AM, Pienta KJ, Brown M. A hierarchical network of transcription factors governs androgen receptor-dependent prostate cancer growth. Mol cell. 2007;27(3):380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner T. The promoter connection. Nat Genet. 2001;29(2):105–106. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullin RP, Dobi A, Mutton LN, Orosz A, Maheshwari S, Shashikant CS, Bieberich CJ. A FOXA1-binding enhancer regulates Hoxb13 expression in the prostate gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(1):98–103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan M. Deciphering modular and dynamic behaviors of transcriptional networks. Genomic Med. 2007;1(1–2):19–28. doi: 10.1007/s11568-007-9004-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartharius K, Frech K, Grote K, Klocke B, Haltmeier M, Klingenhoff A, Frisch M, Bayerlein M, Werner T. MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(13):2933–2942. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda K, Werner T, Maheshwari S, Frisch M, Oh S, Petrovics G, May K, Srikantan V, Srivastava S, Dobi A. Androgen receptor binding sites identified by a GREF_GATA model. J of mMol Biol. 2005;353(4):763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz F, Furlong EE. Transcription factors: from enhancer binding to developmental control. Nature reviews Genetics. 2012;13(9):613–626. doi: 10.1038/nrg3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hihnala S, Kujala M, Toppari J, Kere J, Holmberg C, Hoglund P. Expression of SLC26A3, CFTR and NHE3 in the human male reproductive tract: role in male subfertility caused by congenital chloride diarrhoea. Mol human Reprod. 2006;12(2):107–111. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan PY, Chang CW, Chng KR, Wansa KD, Sung WK, Cheung E. Integration of regulatory networks by NKX3-1 promotes androgen-dependent prostate cancer survival. Mol and cell Biol. 2012;32(2):399–414. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05958-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt L, Fuchs S, Krohn A, Masser S, Mader M, Kluth M, Bachmann F, Huland H, Steuber T, Graefen M. et al. CHD1 is a 5q21 tumor suppressor required for ERG rearrangement in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(9):2795–2805. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Q, Jiao J, Xin L, Chang CJ, Wang S, Gao J, Gleave ME, Witte ON, Liu X, Wu H. NKX3.1 stabilizes p53, inhibits AKT activation, and blocks prostate cancer initiation caused by PTEN loss. Cancer cell. 2006;9(5):367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song LN, Bowen C, Gelmann EP. Structural and functional interactions of the prostate cancer suppressor protein NKX3.1 with topoisomerase I. The Biochem J. 2013;453(1):125–136. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide T, Ramberg H, Glackin C, Tindall D, Tasken KA. TWIST1, A novel androgen-regulated gene, is a target for NKX3-1 in prostate cancer cells. Cancer cell Int. 2013;13(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vij N, Mazur S, Zeitlin PL. CFTR is a negative regulator of NFkappaB mediated innate immune response. PloS one. 2009;4(2):e4664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowski MC, Bowen C, Gelmann EP. Inflammatory cytokines induce phosphorylation and ubiquitination of prostate suppressor protein NKX3.1. Cancer Res. 2008;68(17):6896–6901. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara DB, Vaghasia AM, Yu SH, Mak TN, Bruggemann H, Nelson WG, De Marzo AM, Yegnasubramanian S, Sfanos KS. A mouse model of chronic prostatic inflammation using a human prostate cancer-derived isolate of Propionibacterium acnes. Prostate. 2013;73(9):1007–1015. doi: 10.1002/pros.22648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debelec-Butuner B, Alapinar C, Varisli L, Erbaykent-Tepedelen B, Hamid SM, Gonen-Korkmaz C, Korkmaz KS. Inflammation-mediated abrogation of androgen signaling: an in vitro model of prostate cell inflammation. Mol Carcinog. 2012 Aug 21. doi:10.1002/mc.21948. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Khalili M, Mutton LN, Gurel B, Hicks JL, De Marzo AM, Bieberich CJ. Loss of Nkx3.1 expression in bacterial prostatitis: a potential link between inflammation and neoplasia. The Am Jof pathology. 2010;176(5):2259–2268. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.080747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed AA, Tan SH, Sun C, Shaheduzzaman S, Hu Y, Petrovics G, Chen Y, Sesterhenn IA, Li H, Sreenath T. et al. ERG oncogene modulates prostaglandin signaling in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Biol & therapy. 2011;11(4):410–417. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.4.14180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovics G, Liu A, Shaheduzzaman S, Furusato B, Sun C, Chen Y, Nau M, Ravindranath L, Dobi A, Srikantan V. et al. Frequent overexpression of ETS-related gene-1 (ERG1) in prostate cancer transcriptome. Oncogene. 2005;24(23):3847–3852. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwamukonda K, Chen Y, Ravindranath L, Furusato B, Hu Y, Sterbis J, Osborn D, Rosner I, Sesterhenn IA, McLeod DG. et al. Quantitative expression of TMPRSS2 transcript in prostate tumor cells reflects TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status. Prostate cancer and prostatic Dis. 2010;13(1):47–51. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2009.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter E, Masuda K, Cook C, Ehrich M, Tadese AY, Li H, Owusu A, Srivastava S, Dobi A. A role for DNA methylation in regulating the growth suppressor PMEPA1 gene in prostate cancer. Epigenetics: Off J of the DNA Methylation Soc. 2007;2(2):100–109. doi: 10.4161/epi.2.2.4611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

NFкB forms the central node of predicted NKX3.1 target genes within the human genome.

IDs of annotated genes (1037) obtained from the list of non-redundant model matches of predicted NKX3.1 targets within the human genome. The TMPRSS2 gene ID is underlined on chromosome 21.