Abstract

Population-based surveys in Southern Africa suggest a substantial burden of undiagnosed HIV-infected long-term survivors of mother-to-child transmission. We conducted an HIV prevalence survey of primary school pupils in Harare, Zimbabwe, and evaluated school-linked HIV counselling and testing (HCT) for pupils, their families and schoolteachers. Population-weighted cluster sampling was used to select six primary schools. Randomly selected class-grade pupils underwent anonymous HIV testing, with concurrent school-linked family HCT offered during the survey. Focus group discussions and interviews were conducted with pupils, parents/ guardians, counsellors, and schoolteachers. About 4386 (73%) pupils provided specimens for anonymous HIV testing. Median age was 9 years (IQR 8–11), and 54% were female. HIV prevalence was 2.7% (95% CI: 2.2–3.1) with no difference by gender. HIV infection was significantly associated with orphanhood, stunting, wasting, and being one or more class grades behind in school due to illness (p <0.001). After adjusting for covariates, orphanhood and stunting remained significantly associated with being HIV positive (p <0.001). Uptake of diagnostic HIV testing by pupils was low with only 47/4386 (1%) pupils undergoing HCT. The HIV prevalence among children under 15 years who underwent HIV testing was 6.8%. The main barrier to HIV testing was parents’ fear of their children experiencing stigma and of unmasking their own HIV status should the child test HIV positive. Most guardians believed that a child's HIV-positive result should not be disclosed and the child could take HIV treatment without knowing the reason. Increased recognition of the high burden of undiagnosed HIV infection in children is needed. Despite awareness of the benefits of HIV testing, HIV-related stigma still dominates parents/guardians' psychological landscape. There is need for comprehensive information and support for families to engage with HIV testing services.

Keywords: Africa, HIV, HCT, primary school pupils, stigma

Introduction

While untreated HIV infection in infancy is associated with a high risk of early mortality (Newell et al., 2004), it is estimated that a third of HIV-infected infants experience slow-progressing disease with a 50% probability of survival to 16 years without treatment (Ferrand et al., 2009; Stover, Walker, Grassly, & Marston, 2006). There is, however, a lack of empirical data as most HIV prevalence surveys exclude children or report age-aggregated surveillance data.

HIV diagnosis in children is often delayed until presentation with symptomatic disease (Ferrand, Bandason, Musvaire et al., 2010). HIV testing in healthcare services relies on children having symptoms and may not be sufficient for timely identification of HIV-infected children. We investigated the burden of HIV among primary school pupils, and evaluated school-linked HIV counselling and testing (HCT).

Methods

An anonymous HIV prevalence survey of primary schools pupils was conducted between January and November 2010. Six schools in six high-density suburbs of western Harare were randomly selected using two-stage weighted cluster sampling. Classes per grade were randomly selected, providing an average of 1000 pupils per school to achieve a target sample size of 6000 pupils.

Demographic data, school absenteeism were recorded, height and weight were measured and a venous blood sample collected for anonymised HIV testing. HIV testing was performed using a rapid antibody test (Abbott Determine™), with positive tests confirmed using a different assay (SD Bioline™) and a discordant test result resolved using a third test (Oraquick™), on the same sample.

During the survey period, HCT was offered to teachers, pupils and their family members at community centres located in close proximity to each school. HCT for pupils was performed with the consent of and in the presence of parents/guardians. The study provided CD4 count testing, a month's supply of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis and referral to the nearest HIV services to individuals testing HIV positive.

Qualitative data were collected in four randomly selected study schools. Teachers, pupils (only grades 6–7, age range 11–13 years), parents/guardians and HCT counsellors participated in focus group discussions (FGD) (teachers = 3; pupils = 6; parents = 5, counsellors = 2), and informal interviews (parents/guardians = 7; counsellor = 1; exit interviews with caregivers of children who underwent HCT = 4). A total of 131 participated in discussions (interviews parents = 3; FGD pupils = 31; FGD parents = 55; FGD teachers = 29; FGD counsellors = 5; exit interviews with caregivers attending for school-linked testing = 8). There was equal gender representation among all groups. Teachers were randomly selected from those who stated they had a suspected HIV-positive pupil in their class. Playground observation was conducted in two schools.

Quantitative analysis was performed using STATA v10.0. Explanatory variables were examined for bivariate association with HIV and adjusted for confounding and school clustering. Qualitative discussions were audio recorded, transcribed and translated and analysed using grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

Adult participants provided written consent, and pupils with parent/guardian consent gave written assent to participate. Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe and the Ethics Committees of the Biomedical Research and Training Institute IRB and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Results

HIV prevalence

A total of 4386 (73%) pupils participated in the HIV prevalence survey. Median age was 9 years (IQR: 8–11), 2387 (54%) were female and 784 (18%) were orphans (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 4386) |

|---|---|

| Age-group | |

| ≤ 10 years | 2938 (67.0%) |

| > 10 Years | 1448 (33.0%) |

| Median age | 9 years (IQR 8–11 years) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1999 (45.6%) |

| Orphan | |

| Paternal | 473 (10.8%) |

| Maternal | 150 (3.6%) |

| Double | 153 (3.5%) |

| ≥1 class year behinda | |

| Yes | 181 (4.1%) |

| Stuntingb | |

| Yes | −0.25 (IQR −0.94 to 0.49) |

| Median height-for age | 49 (1.1%) |

| z-score | |

| Wastingc | |

| Yes | 218 (5.0%) |

| Median weight-for age | –0.32 (IQR −0.97 to 0.32) |

| z-score | |

Notes: aDue to illness.

Height-for-age z-score < − 2.

Weight-for-age z-score < − 2.

HIV prevalence was 2.7% (95% CI: 2.2–3.1%), significantly higher in > 10 year olds vs younger pupils (3.5 vs 2.2%, p = 0.008). There was no significant difference in HIV prevalence by gender, but orphanhood, stunting, wasting and being behind ≥ 1 class grade for age were significantly associated with being HIV positive. After adjusting for covariates, HIV-infected pupils had four times higher odds of being orphaned (AOR 3.9; 95% CI: 2.3–6.5) and 11 times higher odds of being stunted (AOR 11.2; 95% CI: 4.9–25.7) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with being HIV infected among primary school children (N = 4386).

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HIV prevalence N = 117 (2.7%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

| Age group | |||||

| > 10 years | 3.6% | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) | 0.009 | – | – |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 2.8% | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 0.671 | – | – |

| Orphan | |||||

| Yes | 7.0% | 4.3 (2.7–6.9) | <0.001 | 3.9 (2.3–25.7) | 0.001 |

| ≥ 1 class year behinda | |||||

| Yes | 18.4% | 8.8 (2.1–36.9) | 0.011 | – | – |

| Stuntingb | |||||

| Yes | 19.9% | 12.6 (5.7–27.8) | <0.001 | 11.2 (4.9–25.7) | 0.001 |

| Wastingc | |||||

| Yes | 14.2% | 7.9 (3.7–16.8) | 0.001 | – | – |

Notes: aDue to illness.

Height-for-age z-score < − 2.

Weight-for-age z-score < − 2.

Uptake and evaluation of school-linked HCT

While 1886 individuals tested through the HCT service, only 47 (2.5%) were primary school pupils. HIV prevalence among children aged < 15 years was 6.8%, significantly higher (p < 0.04) than the survey prevalence, suggesting that parents/guardians of children who underwent HIV testing were likely to have suspected their child was infected (Table 3).

Table 3.

Uptake of school-linked HIV counselling and testing.

| No (N = 1886) | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| School children | 47 | 2.5 |

| Siblingsa | 36 | 1.9 |

| Biological mother | 80 | 4.2 |

| Biological father | 22 | 1.2 |

| Other relatives | 1633 | 86.6 |

| Teachers | 68 | 3.6 |

| Total adults tested (≥ 15 years) | 1827 | 96.9 |

| Total children tested (< 15 years) | 59 | 3.1 |

Note: aTwenty-four siblings were aged 15 years or older.

Overall, guardians appreciated the benefits of HIV testing, and knew that effective treatment that would enable a child to live a healthy life was available (Table 4: themes 1, 2, 3). However, this understanding did not apply when thinking about their child.

Table 4.

Themes and quotes from qualitative survey.

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| (1) Community awareness of benefits of HIV testing connected to accessing treatment | 1.1 The child might survive and also do all the activities that are done by other children. (FGD, cmtyl, parent5) |

| 1.2 A lot of people are now aware because many people are going around [openly] saying, ‘I thought I was dead but I have actually survived.’ (FGD, cmty4, parent2) | |

| (2) Protecting children from distressing news | 2.1 I had a funeral in the counselling room. They were about five [of them]. They all started screaming. To them this child is dying… it is a challenge. These people are screaming like this: what are they going to do to the child when they get home? How are they going to help this child? (HCT counsellor 3) |

| 2.2 When they go to play with their friends, mothers would then say, ‘Go away from here because you have AIDS. You will infect our children with AIDS. Move away and play at your house.’ (FGD, cmty4, pupill) | |

| 2.3 Sometimes they are scared; that concern is being driven by fear that this child is going to infect our children. [They ask questions like] ‘how about my cup, how about my plate that he sometimes uses?’ ‘So if she sits on the toilet seat, are we not going to get infected?’ (HCT counsellors 2&3) | |

| 2.4 If some of the children find out, [they] could just start avoiding her. Or refuse to play with her and they will be afraid of her …. so she might end up without any friends (FGD, cmty1, parent6) | |

| 2.5 For a child to tell another child ‥ he can only laugh saying, ‘so this is what you are like, where did you get it and the like? (informal interview, grade2 mother) | |

| 2.6 These are young people;… children can mock each other terribly. And it is not good for a child to be mocked. She will be stressed out and might end up thinking about things that are bad. Maybe she might think of committing suicide. Therefore I am saying it is good for the family to know only. (FGD, cmty4, parent10) | |

| (3) Evidence of a positive shift in perceptions | 3.1 I think it is good. Isn't it we were talking about that boy [whose] father is late? His mother was ill and he has been ill for 12 years. I realized that when they got tested they supported one another and said, ‘we are in this situation [together]'. I can actually see that it would be good if both the parent and the child are tested. (informal interview, cmty3) |

| 3.2 Yes, as the child's parent I should also get tested. If my child tests positive to HIV, I should agree to get tested so that I will be able to get treatment together with the child. (FGD, cmty2, parent9) | |

| 3.3 Sharing helps. Sharing things like food helps because you will find some refusing to eat with her. (FGD, cmty2, teacher9) | |

| 3.4 I am not saying that she will not agree, but I want to say that if she has love for her brother's child, she could let her get tested…. Because a person who wants someone to be tested is interested in protecting that person's health. (FGD, cmty1, parent2) | |

| (4) Internalised self isolating behaviour | 4.1 During participant observation, pupils who were actively playing together tried unsuccessfully to include another child. When pressed, she acknowledged that she was ‘sick’ and was worried that she might pass on her illness to the other pupils if she played with them. (participant observation, cmty4) |

| (5) A child's HIV status reflects that of the parents | 5.1 There is no way that this child could have been infected except through me as the parent. (FGD, cmty1, parent7) |

| 5.2 When you know [that your child is HIV +], that will make you die promptly. (informal interview, grade 4 mother) | |

| 5.3 I am afraid that when we go for testing as a family I might test positive to HIV while my parents are negative. I am afraid that they might wonder where I contracted it from. (FGD, cmty3, pupil6) | |

| 5.4 I would be worried that if my child is tested and is HIV positive, how about my own status? Maybe I am also HIV positive which will stress me out. (FGD, cmty2, parent1) | |

| (6) Test but don't disclose | 6.1 I am not able to tell him. So its better that I tell my older sister in case I might travel and my child might need to take his pills…. and if he asks me ‘what are [the pills] for?’ I will tell him ‘they are pills you are supposed to take for you painful stomach or headache.’ Or I could tell him that ‘these are pills for you to be good in school’ so that he does not get frustrated. (informal interview, grade 2 mother) |

| (7) Health care workers’ concerns | 7.1 Zimbabwe we have a challenge that people have not yet reached the level of accepting it. They [still] think this disease is for people that are promiscuous and are prostitutes. (FGD, cmty3, parent1) |

| 7.2 Not having a language to talk about HIV to young people, because all of our focus has been on multiple partners, so there is nothing relevant for young people…. It takes time to find the appropriate language that … can be understood by a child. (HCT counsellor1) | |

| 7.3 It is also difficult to [explain to] the child that they might have been infected by their mother or father. There is need to include biology which is difficult for a child to comprehend. (HCT counsellor1) | |

| 7.4 At times you had to ask a child; ‘before coming here with your parent or guardian, were you told anything about why you are here or do you understand what will be going on?'. You would then hear them saying ‘they told me that we are here for this reason', which will be a different story altogether. It then becomes a challenge because you wouldn't know how to break the news to the child when she has not been told by the parent or the guardian. (HCT counsellor2) |

Two principal reasons were highlighted by parents/guardians for not testing their children: (1) parents’ concerns that their child's HIV-positive status would unmask their own and (2) a desire to protect children from stigmatising experiences and “knowing bad things”. Words like “stressed”, “isolated”, “lonely” and “suicidal” were used to describe their perception of a child's reaction to an HIV diagnosis. Pupils often concurred and playground observation confirmed self-isolating behaviour (Table 4: theme 4). HCT counsellors, however, revealed that children's fears were a consequence of their parents/guardians’ fears rather than their own (Table 4: theme 2).

Counsellors stated that the “language” they had been trained to use to discuss HIV was centred on sexual transmission. This not only made discussing HIV with children difficult but also helped promote stigmatising behaviours towards children (Table 4: theme 2). Moreover, unlike in adults, HIV infection in children has visible manifestations like shorter stature, missed school and skin rashes (Berhane et al., 1997; Lowe et al., 2010; Padmapriyadarsini et al., 2009), and pupils, parents and teachers described these manifestations as reasons they “knew” a child was HIV infected.

Parents expressed concern that their child's HIV-positive status would automatically disclose their own. This was especially true among men who are culturally responsible for decisions related to family health (Table 4: theme 5). Parents expressed guilt for having infected their children and feared potential tension within the marital relationship and divorce if their HIV status was unmasked by the child's HIV-positive result (Table 4: theme 5). These concerns resulted in discussions that focused on how to test without telling the child (Table 4: theme 6). However, counsellors emphasised the need for children to know their HIV status and encouraged parents/guardians to tell their children during post-test counselling (Table 4: theme 7). Teachers described strategies to counter-stigmatising attitudes within schools, such as sharing lunches (Table 4: theme 7).

Discussion

The study shows a substantial burden of HIV among primary school pupils. While we were unable to ask pupils about previous testing, it is likely that most HIV-infected pupils were undiagnosed (Ferrand, Munaiwa, Matsekete et al., 2010). Children continue to be at risk of HIV infection because of inadequate coverage of interventions to prevent MTCT (average 59% in Southern Africa), and an ongoing risk of postnatal HIV transmission (Taha et al., 2007, 2009; WHO & UNAIDS, 2011). Limited availability of age-appropriate testing services results in many HIV-infected children remaining undiagnosed until presentation with a severe HIV-associated illness. This can occur in late childhood following many years of ill-health, that could have been prevented with earlier diagnosis (Ferrand, Munaiwa, Matsekete et al., 2010).

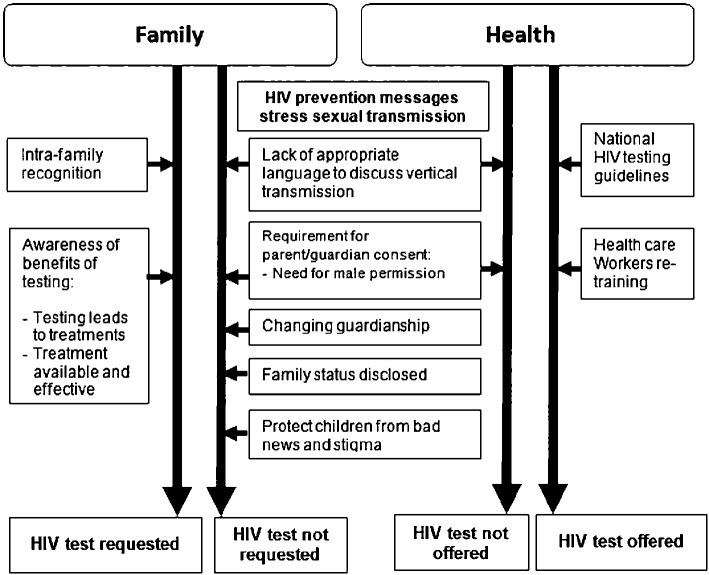

Our data indicate a high level of community awareness around benefits of HIV testing, but strong reluctance to have children tested, highlighted by low rates of children testing despite high uptake by adult family members. Concern among parents about unmasking their own status and about their children experiencing HIV-related stigma appears to be a stronger determinant of the decision whether to test their children than the perceived health benefits of testing, even when they suspect their children to be HIV infected. Parents/guardians’ desire to protect their children against perceived stigma leads them to conclude that it is better for the child to remain undiagnosed than to experience the potentially negative psychosocial consequences of an HIV-positive diagnosis (Campbell, Skovdal, Mupambireyi, & Gregson, 2010). Since guardian consent is legally required for a child to access testing, parents’ reluctance to test their children poses a considerable, ethically challenging barrier for children's right to healthcare. Orphans, who are at highest risk of being HIV infected, may find it even more difficult to access HIV testing as a result of uncertain or changing guardianship (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework for barriers to diagnosis in older children.

The HIV prevalence survey had a non-participation rate of 27%, mainly due to lack of parental consent. It is possible that parents who knew or suspected their child was HIV positive may have been more likely to decline consent, resulting in an underestimate of HIV prevalence. Another limitation was situating school-linked HCT outside school premises, in line with National policy.

There is a pressing need for effective strategies to address timely diagnosis of HIV in children. Existing policy that encourages health promotion initiatives could enable schools to be a model for delivering HCT to children (MIET-Africa, 2008; UNICEF, 2009). This will require a shift in attitude among parents/guardians and emphasis on providing safeguards against adverse consequences faced by children who are HIV positive. Strategies focused on increasing children's access to HIV testing must include interventions to address prevalent community attitudes. Teachers and healthcare workers also need training on how to reassure caregivers.

Delayed diagnosis puts children at high risk of severe morbidity and mortality. While addressing the psychosocial issues that accompany an HIV diagnosis is important, a child's right to good health remains critical.

Box 1: Approaches to improving HIV diagnosis in children

Prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) programs

Scale up of PMTCT interventions and early infant diagnosis

Strengthening systems for follow-up of HIV-exposed infants

Awareness

Community awareness campaigns of the risk of HIV infection in older children

Training programmes for health care workers

HIV testing

Family-centred HIV testing approaches

Guidelines & training for teachers

Simple non-stigmatising guidelines on managing HIV in classrooms

Acknowledgements

The Prevalence Survey was funded by UNICEF through the OVC for National Action Programme (NAP)

Programme of Support, and the HIV Counselling and Testing (HCT) was funded by CDC, Zimbabwe.

References

- Berhane R., Bagenda D., Marum L., Aceng E., Ndugwa C, Bosch R. J., Olness K. Growth failure as a prognostic indicator of mortality in pediatric HIV infection. Pediatrics. 1997;100(1):e7. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.1.e7. doi:10.1542/peds.100.1.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Skovdal M., Mupambireyi Z., Gregson S. Exploring children's stigmatisation of AIDS-affected children in Zimbabwe through drawings and stories. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;71(5):975–985. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.028. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand R. A., Bandason T., Musvaire P., Larke N., Nathoo K., Mujuru H., Corbett E. L. Causes of acute hospitalization in adolescence: Burden and spectrum of HIV-related morbidity in a country with an early-onset and severe HIV epidemic: A prospective survey. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7(2):e1000178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000178. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand R. A., Corbett E. L., Wood R., Hargrove J., Ndhlovu C. E., Cowan F. M., Williams B. G. AIDS among older children and adolescents in Southern Africa: Projecting the time course and magnitude of the epidemic. Aids. 2009;23(15):2039–2046. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833016ce. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833016ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand R. A., Munaiwa L., Matsekete J., Bandason T., Nathoo K., Ndhlovu C. E., Corbett E. L. Undiagnosed HIV infection among adolescents seeking primary health care in Zimbabwe. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2010;51(7):844–851. doi: 10.1086/656361. doi:10.1086/656361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B., Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe S., Ferrand R. A., Morris-Jones R., Salisbury J., Mangeya N., Dimairo M., Corbett E. L. Skin disease among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents in Zimbabwe: A strong indicator of underlying HIV infection. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2010;29(4):346–351. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181c15da4. doi:10.1093/cid/cis118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIET-Africa. Care and support for teaching and learning: Regional support pack. 2008. Retrieved from http://www.miet.co.za/site/entityview/815/view.

- Newell M. L., Coovadia H., Cortina-Borja M., Rollins N., Gaillard P., Dabis F. Mortality of infected and uninfected infants born to HIV-infected mothers in Africa: A pooled analysis. Lancet. 2004;364(9441):1236–1243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17140-7. doi: 10.1016/S0 140-6736(04)17140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmapriyadarsini C, Pooranagangadevi N., Chandrasekaran K., Subramanyan S., Thiruvalluvan C, Bhavani P. K., Swaminathan S. Prevalence of underweight, stunting, and wasting among children infected with human immunodeficiency virus in South India. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2009. doi:10.1155/2009/837627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stover J., Walker N., Grassly N. C, Marston M. Projecting the demographic impact of AIDS and the number of people in need of treatment: Updates to the spectrum projection package. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2006;82(Suppl 3):iii45–50. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.020172. doi:10.1136/sti.2006.020172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha T. E., Hoover D. R., Kumwenda N. I., Fiscus S. A., Kafulafula G., Nkhoma C, Miotti P. G. Late postnatal transmission of HIV-1 and associated factors. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;196(1):10–14. doi: 10.1086/518511. doi:10.1086/518511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha T. E., Kumwenda J., Cole S. R., Hoover D. R., Kafulafula G., Fowler M. G., Mofenson M. Postnatal HIV-1 transmission after cessation of infant extended antiretroviral prophylaxis and effect of maternal highly active antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009;200(10):1490–1497. doi: 10.1086/644598. doi:10.1086/644598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Focusing resources on effective school health (FRESH) Geneva: UNICEF, WHO, UNESCO and World Bank; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- WHO & UNAIDS. Towards universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. (Progress Report 2011) Geneva: WHO and UNAIDS; 2011. [Google Scholar]