Abstract

Objective To assess at country level the association of mortality in under 5s with a large set of determinants.

Design Longitudinal study.

Setting 193 United Nations member countries, 2000-09.

Methods Yearly data between 2000 and 2009 based on 12 world development indicators were used in a multivariable general additive mixed model allowing for non-linear relations and lag effects.

Main outcome measure National rate of deaths in under 5s per 1000 live births

Results The model retained the variables: gross domestic product per capita; percentage of the population having access to improved water sources, having access to improved sanitation facilities, and living in urban areas; adolescent fertility rate; public health expenditure per capita; prevalence of HIV; perceived level of corruption and of violence; and mean number of years in school for women of reproductive age. Most of these variables exhibited non-linear behaviours and lag effects.

Conclusions By providing a unified framework for mortality in under 5s, encompassing both high and low income countries this study showed non-linear behaviours and lag effects of known or suspected determinants of mortality in this age group. Although some of the determinants presented a linear action on log mortality indicating that whatever the context, acting on them would be a pertinent strategy to effectively reduce mortality, others had a threshold based relation potentially mediated by lag effects. These findings could help designing efficient strategies to achieve maximum progress towards millennium development goal 4, which aims to reduce mortality in under 5s by two thirds between 1990 and 2015.

Introduction

The latest estimates from the United Nations show a decline in the total number of deaths in under 5s, from more than 12 million in 1990 to 6.9 million in 2011.1 However, many countries still have high mortality rates in this age group, with little or no progress in recent years. The mortality rate in under 5s is increasingly concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia, whereas the share in the rest of the world dropped from 31% in 1990 to 17% in 2011. The three leading causes of death among under 5s are pneumonia, preterm birth complications, and diarrhoea.

Since the 1980s, several quantitative studies have attempted to explore global determinants that might have an influence on the mortality rate in under 5s. They provided strong insights, highlighting, for example, the predominant role of national income and other global socioeconomic factors such as access to improved water and sanitation facilities on mortality levels in under 5s.2 3 4 Policy initiatives based on these results in combination with improvements in gross domestic product and other development features have contributed to a noticeable decline in the mortality rate in under 5s in many countries since the 1980s.2 3 4

Despite these achievements, however, most developing countries still lag behind the developed world. This discrepancy led the UN Inter-agency Group to conclude that the rate of decline in mortality in under 5s remains insufficient to achieve the millennium development goal 4, which aims to reduce such mortality by two thirds between 1990 and 2015.1 Furthermore, although the identified factors explain a substantial amount of disparities between nations, debates around the real impact of some determinants have emerged.3 4

Until now, most of the studies describing mortality in under 5s on a global scale were cross sectional,3 4 although longitudinal studies allow a better causal inference than simple cross sectional studies.5 These studies also involved simple regression analyses assuming linear relations. Non-linear relations between the mortality rate in under 5s and its determinants could, however, exist and partly explain the observed differences in the determinants specifically at work in low and high income countries.3 Furthermore, these studies generally focused on immediate action of determinants and neglected their potential lag effects.

We exploited the full range of the observed mortality rate in under 5s by using appropriate models to unravel determinant effects at work in low and high income countries. The use of freely available country specific yearly data on these mortality rates and on a large panel of demographic, political, and socioeconomic global factors overcomes these limitations through longitudinal data modeling allowing for non-linear and lag effects of determinants to be shown.

Methods

Study design and data collection

This 10 year longitudinal study was performed at country level. We aimed to identify determinants of mortality in under 5s, defined as the national rate of deaths in under 5s per 1000 live births, using yearly data compiled by the UN and freely available on the World Bank website. The analysis was performed on data from the 193 UN member countries for 2000 to 2009 (see supplementary appendix 1).

According to the literature, the main global risk factors for deaths in children are non-access to drinkable water and sanitation facilities,6 urbanisation,7 low socioeconomic conditions,8 women’s education,9 level of health services,10 undernourishment,11 prevalence of HIV,12 early pregnancy among adolescents,13 and political and societal context.14 To quantify the association of mortality in under 5s with these determinants, we used data compiled by the UN and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. We investigated the association between the mortality rate in under 5s and 12 independent variables describing the main global risk factors of each country. We also collected data quantifying the level of these variables between 1996 and 1999 in view of investigating their potential short term effect (defined here as a two year lag) or medium term effect (defined here as a four year lag) on the mortality rate in under 5s. We also considered two adjustment variables, defined as the measurement year and the World Bank region (six levels) to which the country belongs.

Imputation of missing values

Owing to incomplete data for some determinants, only 127 countries from the 193 ones were completely observed during at least one year. Since limiting the analysis to this subset is inefficient and implies a risk of selection bias,15 we used multiple imputation. To obtain 10 completed datasets we substituted 10 plausible values for the missing ones, in agreement with what was observed in the data. We analysed each of these using standard complete data methods. The Rubin’s formulas were then used to synthesise the results and formally incorporate the uncertainty about the true missing values.15 Multiple imputation was performed with the Amelia II software (see supplementary appendix 2).

Statistical analysis

Generalised additive models provide a well suited modeling framework for uncovering trends in potentially non-linear multivariate data. Their main advantage over simple regression methods is their capability to finely model non-linearities in the relations between an output and a set of variables.16 A small number of simple polynomial (quadratic or cubic) curves are fitted to successive segments of the data using a continuity constraint to preserve smoothness at the knots delimiting the segments. Generalised additive mixed models include random effects to take into account correlation patterns in repeated outcomes.

To satisfy the homoscedasticity assumption we fitted these models to log transformed mortality rates in under 5s. We implemented generalised additive mixed models for normally distributed data. The random intercept was allowed to vary between countries according to a gaussian distribution. This generalised additive mixed model has been developed based on the assumption that all measures from the same country are similarly correlated. To avoid overfitting, we fitted cubic curves to the data assuming the presence of five segments. We plotted the final relations between the logarithm of mortality rate in under 5s and the variables included in the final generalised additive mixed model.

All studied variables were used to identify the best final multivariable model by means of forward stepwise procedures based on the Akaike information criterion. We performed a stepwise procedure for each imputed dataset, leading to several different models. As suggested elsewhere, the selected exploratory variables were those that appeared in more than half of the models (see supplementary appendix 3).17 We then ran the model incorporating all these selected variables with each imputed dataset and used the Rubin’s formula to synthesise the associated results. From the model we also removed variables for which the confidence interval of the effect included zero for all observed values.

The robustness of results was tested by performing separate analyses for low income and high income countries (see supplementary appendix 4) and by using different models specification (see supplementary appendices 5 and 6). We assessed graphically the homoscedasticity and normality of residuals in the final model. Absence of economic or temporal residual correlations was also checked graphically (see supplementary appendix 7). All statistical analyses were conducted using R 2.14.3.

Results

The table summarises the distributions of selected variables. Supplementary appendix 8 presents Pearson’s correlations between all these variables. The final generalised additive mixed model included 15 variables in addition to year and region indicators.

Distribution characteristics of mortality in under 5s and of studied variables that potentially can explain variations between countries (n=193), 2000 and 2009

| Characteristics | Mean | Centiles | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% | 50% | 75% | ||

| Variable of interest | ||||

| Death in under 5s per 1000 live births | 49 | 10 | 25 | 79 |

| Demographic and socioeconomic factors | ||||

| GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity (current international $): | ||||

| Lag 0 | 11 571 | 1968 | 5863 | 16 282 |

| Lag 2 | 10 505 | 1778 | 5215 | 14 388 |

| Lag 4 | 9476 | 1644 | 4629 | 12 900 |

| People with access to improved water sources (%): | ||||

| Lag 0 | 84 | 77 | 92 | 99 |

| Lag 2 | 83 | 75 | 91 | 99 |

| Lag 4 | 82 | 72 | 90 | 99 |

| People with access to improved sanitation facilities (%): | ||||

| Lag 0 | 69 | 45 | 82 | 97 |

| Lag 2 | 69 | 43 | 81 | 97 |

| Lag 4 | 68 | 40 | 80 | 97 |

| Mean No of years in school for women of reproductive age (15-45 years): | ||||

| Lag 0 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 11 |

| Lag 2 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 11 |

| Lag 4 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 11 |

| Percentage of urban population: | ||||

| Lag 0 | 54 | 34 | 54 | 73 |

| Lag 2 | 53 | 33 | 53 | 73 |

| Lag 4 | 53 | 33 | 53 | 72 |

| Adolescent fertility rate (births per 1000 women aged 15-19): | ||||

| Lag 0 | 57 | 19 | 43 | 83 |

| Lag 2 | 59 | 20 | 45 | 86 |

| Lag 4 | 61 | 21 | 47 | 90 |

| Health and medical factors | ||||

| Public health expenditure per capita based on purchasing power parity (current $): | ||||

| Lag 0 | 541 | 44 | 190 | 617 |

| Lag 2 | 479 | 39 | 166 | 526 |

| Lag 4 | 429 | 33 | 141 | 479 |

| HIV prevalence (%): | ||||

| Lag 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Lag 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Lag 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Prevalence of undernourishment (% of population): | ||||

| Lag 0 | 15 | 5 | 8 | 21 |

| Lag 2 | 16 | 5 | 8 | 23 |

| Lag 4 | 16 | 5 | 9 | 24 |

| Political and societal factors | ||||

| Perceived level of corruption*: | ||||

| Lag 0 | −0.08 | −0.82 | −0.34 | 0.46 |

| Lag 2 | −0.08 | −0.84 | −0.32 | 0.49 |

| Lag 4 | −0.07 | −0.85 | −0.31 | 0.53 |

| Perceived level of democracy†: | ||||

| Lag 0 | −0.07 | −0.90 | −0.09 | 0.85 |

| Lag 2 | −0.07 | −0.89 | −0.10 | 0.85 |

| Lag 4 | −0.07 | −0.86 | −0.12 | 0.86 |

| Perceived level of violence‡: | ||||

| Lag 0 | −0.09 | −0.78 | 0.01 | 0.77 |

| Lag 2 | −0.10 | −0.81 | −0.01 | 0.77 |

| Lag 4 | −0.11 | −0.81 | −0.04 | 0.76 |

GDP=gross domestic product.

Lags effects: immediate (lag 0), short term (lag 2), and medium term (lag 4) effects.

*World governance indicator on control of corruption.

†World governance indicator on voice and accountability.

‡World governance indicator on political stability and absence of violence and terrorism.

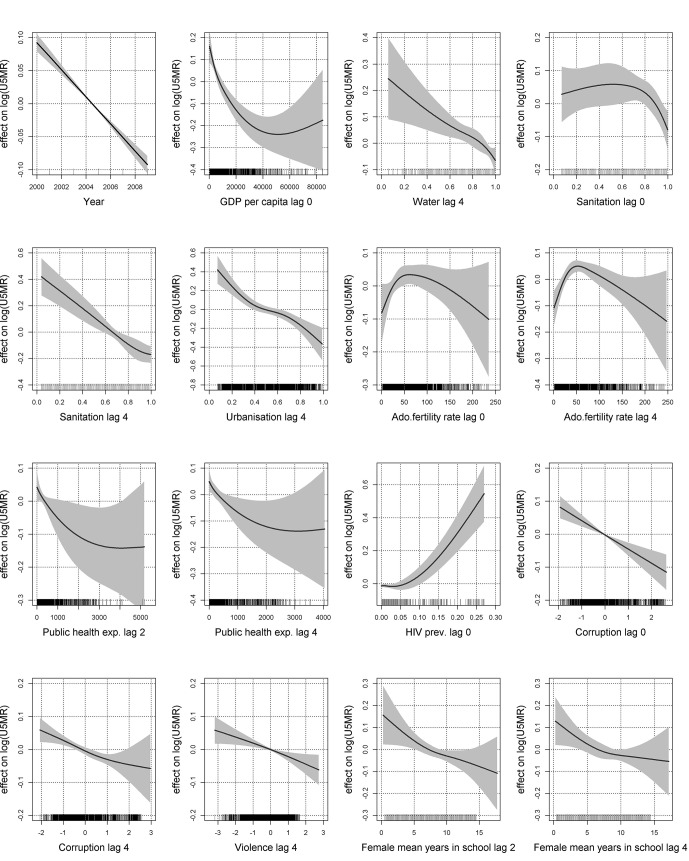

The selected variables were the gross domestic product per capita; percentage of the population having access to improved water sources, having access to improved sanitation facilities, and living in urban areas; adolescent fertility rate; public health expenditure per capita; prevalence of HIV in the general population; perceived level of corruption and of violence; and mean number of years in school for women of reproductive age (figure).

Relations between logarithm of mortality rate in under 5s and 16 continuous variables included in final generalised additive mixed model. Y axis is effect of variable on log(mortality rate in under 5s); grey areas are 95% confidence intervals; rug plots on S axis are observed values. GDP=gross domestic product

The gross domestic product per capita, percentage of population having access to improved sanitation facilities, adolescent fertility rate, prevalence of HIV, and perceived level of corruption were found to have at least an immediate action on mortality in under 5s (lag 0). Delayed actions were found for all other selected variables (lag 2 or 4, or both).

A strictly monotonic impact on mortality in under 5s was only observed for the percentage of the population having access to improved sanitation facilities (lag 4), percentage of the population having access to improved water sources, percentage of the population living in an urban area, and perceived level of corruption and of violence. All others variables exhibited a threshold based relation with mortality in under 5s.

Two different lags were selected by the stepwise procedures for the following variables: population having access to improved sanitation facilities (lags 0 and 4), adolescent fertility rate (lags 0 and 4), public health expenditure per capita (lags 2 and 4), perceived level of corruption (lags 0 and 4), and mean number of years in school for women of reproductive age (lags 2 and 4). Except for the percentage of the population having access to improved sanitation facilities, similar shapes in the relation with mortality in under 5s were found at each lag for these variables. All other variables were only present in the model at a single lag (lags 0, 2, or 4).

Plots of residuals versus predicted values and quantile-quantile plot did not reveal any strong pattern and indicated that homoscedasticity and normal hypothesis could be assumed. Others sensitivity analyses did not reveal any problems in relation to the chosen number of knots or the smoothing constraint or to residual economic or temporal correlations (see supplementary appendices 4-7).

Discussion

By providing a unified framework for mortality in under 5s, encompassing both high and low income countries this study showed non-linear behaviours and lag effects of known or suspected determinants of mortality in this age group. Although some of the determinants presented a linear action on log mortality others had a threshold based relation potentially mediated by lag effects.

Limitations of this study

The analysis presented here had its limitations. Firstly, ecological studies are known to be prone to bias.18 Secondly, this study relied on aggregated data estimated by the UN. Other estimations relying on different assumptions and data sources could be considered.19 Thirdly, some effects might be biased by not considering unavailable important factors such as breast feeding20 or inequality in incomes.21 It was assumed that the inclusion in the final model of year and region as fixed effects partly limited this bias by acting as proxy variables for these unmeasured variables. A fourth limitation was the adopted definition of lag effects of the determinants of mortality in under 5s. Three types of lag effects were considered: immediate (lag 0), short term (lag 2), and medium term (lag 4). Identified lags were thus only rough indicators and did not perfectly reflect the temporal gradient of determinant action. Fifthly, we included countries with a high heterogeneity for mortality in under 5s and its determinants in the same analysis. Although we considered non-linear actions, the socioeconomic and cultural context of low income countries compared with that of high income countries might act as an effect modifier and potentially determine different significances and shapes of the relations. Stratified analyses separating these two kinds of countries did not reveal major differences, suggesting that this phenomenon was limited. Despite these limitations, the range of observed confidence intervals gave a convincing argument for the effective presence of strong non-linear relations between mortality in under 5s and some of its determinants and for the importance of considering lag effects.

Identified determinants and mortality in under 5s

National level determinants of mortality in under 5s explaining differences between countries have been extensively studied. Among them, national income is certainly the most acknowledged.4 The present analysis showed that the gross domestic product seemed to impact the mortality in under 5s through an immediate action. As an economy grows, there are more direct resources to rapidly improve nutrition, access to medical care, housing, and other conditions that are related to better health. Furthermore, the associated relation with mortality in under 5s indicated that more than about $40 000 per capita, based on purchasing power parity, further improvements in a nation’s economy had a limited impact on mortality in under 5s. Such a result supports the proposition that when economic development reaches a certain threshold, its effect on child health levels. A delayed action of gross domestic product on mortality in under 5s could nevertheless not be excluded because of a tendency of stepwise procedures to also select either lag 2 or lag 4 concomitantly with lag 0, and of lagged indirect actions on other global determinants.

Despite progress in recent decades, water and sanitation services are still severely lacking in low income countries, and diseases associated with poor water and sanitation still have considerable public health consequences.22 The present study showed a strictly monotonic relation between mortality in under 5s and access to both water and sanitation facilities. These effects appeared as medium term suggesting that what is important is the child’s cumulative exposure to health hazards associated with a lack of water and sanitation facilities. These results were coherent with those of a previous study.6 An immediate action of sanitation coverage was also found for high levels of sanitation coverage. Sensitivity analyses suggested that this effect may hold mainly for high income countries. The fact that high sanitation coverage in such countries may directly impact the transmission dynamics of associated infectious diseases constitutes here a plausible assumption.

Similarly to income, urbanisation affected mortality in under 5s in the expected direction: rural populations were lagging behind their urban counterparts. The higher the percentage of the population living in urban areas, the lower the mortality in under 5s. Sensitivity analyses revealed that this effect may be larger in low income countries than in high income countries. Interestingly, this study also revealed that urbanisation seemed to have a delayed effect on mortality in under 5s.

The adolescent fertility rate was associated with mortality in under 5s and was characterised by highly non-linear behaviours mediated in the short and medium term. At both lags, mortality strongly rose concomitantly with the adolescent fertility rate up to a threshold value of around 50 births/1000 women aged between 15 and 19 years. Above this value, the impact of adolescent fertility rate on mortality in under 5s was estimated with large confidence intervals but seemed to decrease or level. Sensitivity analyses revealed that the increase in mortality associated with that of adolescent fertility rates was only observed in high income and upper middle income countries. It may be hypothesised that adolescent fertility rate is related more to other studied determinants in low income than in high income countries.

One of the most fundamental yet unresolved issues in health policy is whether public spending on healthcare improves health outcomes.4 In the special case of mortality in under 5s, the effect of public spending is still being debated.4 23 In this analysis, it was associated with such mortality through a clear delayed action. Nevertheless, as suggested by the stepwise procedures, a less important immediate action of public health expenditure could not be excluded. In any case the large confidence intervals impeded the interpretation.

In 2009, around 162 000 children died of HIV.24 It is now admitted that the HIV associated increase in mortality in under 5s may simultaneously be due to direct HIV transmission from mother to child and to indirect effects mediated by maternal illness or maternal death.12 Accordingly, the prevalence of HIV in the general population was found in this study as having a clear impact on mortality in under 5s. Its non-linear impact confirmed that in a low prevalence setting an HIV epidemic is not likely to affect mortality in under 5s. However, a clear association was observed in countries with prevalence over 5%. This threshold agreed with the one found by a previous study.25 In addition, the identified immediate action suggested that HIV prevalence acts mainly on mortality in under 5s through direct transmission from mother to child, known to greatly affect children’s survival in the first year of life,26 and highlighted the need for the prevention of peripartum and postnatal transmission.

Recent reports emanating from various institutions assert that corruption could be one of the primary causes for the global community already being off target to meet the millennium development goal 4.27 To our knowledge, only three studies reported a significant link between corruption and mortality in under 5s at a country level.28 29 30 The current analysis clarified the picture a little further. It indicated that both an immediate and a medium delayed effect of corruption on mortality in under 5s could be present, suggesting that corruption impacts on the mortality by simultaneously disrupting immediate accessibility to and quality of health systems, and long term national health investments (for example, construction of health facilities, education of health professionals). The observed relations also suggested that anticorruption measures might be effective ways of reducing mortality in under 5s in all countries whatever the initial level of corruption.

Direct and indirect health consequences of violence are suspected to be major drivers of children’s health.31 However, studies quantifying its impact on mortality in under 5s have been difficult to document. This study confirmed that violence could be a major determinant of mortality in under 5s at a country level. The medium term suggested an indirect action emerging with consecutive disruptions to basic health or other governmental services. The associated relation also indicated that, whatever the context, promoting peace might be a pertinent strategy to reduce mortality in under 5s.

Past studies of global determinants of mortality in under 5s have often reported that maternal education plays an important role in determining child survival even after controlling for several socioeconomic factors.10 Possible pathways put forward are that educated mothers are more likely to adopt preventive behaviours or to recognise the severity of disease, seek treatment, and find good care for their children. Some investigations persist: it is reasonable to wonder whether below or above a certain level, further improvements in the education of a nation’s women have little impact on mortality in under 5s and whether maternal education has a lag effect on such mortality. The present study indicated that women’s education acted mainly through the short and medium term on mortality in under 5s and was negatively associated with mortality up to 5-7 years of schooling, and seemed to level after this threshold whatever the lag considered.

Surprisingly, undernourishment did not appear as a clear determinant of mortality in under 5s. What can be said from this result? Definitively not that undernourishment does not kill children. Undernourishment should rather be seen as a proximal determinant of other global determinants of mortality in under 5s. Similarly for undernourishment, no clear action of the perceived level of democracy was found. The previously observed relation between democracy and health is likely to be mediated by other variables included in our model.32

Conclusion

This study tried to reassess more finely the determinants of mortality in under 5s at a country level. It showed that while some determinants, such as corruption, had a strictly monotonic effect on the mortality rate, indicating that whatever the context, acting on them would be a pertinent strategy to effectively reduce mortality in under 5s in both the short and medium terms, others, such as gross domestic product per capita or HIV prevalence, had a complex action on the mortality rate potentially mediated by lag effects. Such methodology could be generalised to other health outcomes to achieve maximum progress in the next few years and be as close as possible to the millennium development goals and sustainably improve global health.

What is already known on this topic

Several studies have already explored global determinants that might have an influence on the mortality rate in under 5s

Insights were provided on the role of national income and other global socioeconomic factors on mortality levels in under 5s

What this study adds

This study provides a unified framework for both low and high income countries

Identified determinants often present a threshold based relation with mortality rate in under 5s

The influences of indentified determinants on mortality rate in under 5s are often characterised by lag effects

We thank Valérie Briand, Alexandre Dumont, and Michel Cot for their advice and comments about the draft.

Contributors: MH initiated the study, participated in the research design, performed data analysis and interpretation, and prepared the manuscript. He is the guarantor. MN, CG, and PTB helped in interpretation and participated in manuscript revision. MC participated in the research design, provided guidance on data analyses, and was involved in the interpretation of data and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The corresponding author (MH) confirms that he had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. He affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

Funding: This study was supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche. The funder had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;347:f6427

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary appendices

References

- 1.You D, Jones G, Wardlaw T. Levels and trends in child mortality report 2012. United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation, 2012.

- 2.Rutstein SO. Factors associated with trends in infant and child mortality in developing countries during the 1990s. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:1256-70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schell CO, Reilly M, Rosling H, Peterson S, Ekström AM. Socioeconomic determinants of infant mortality: a worldwide study of 152 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Scand J Public Health 2007;35:288-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGuire JW. Basic health care provision and under-5 mortality: a cross-national study of developing countries. World Develop 2006;34:405-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.08.004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frees EW. Longitudinal and panel data: analysis and applications in the social sciences. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- 6.Fink G, Günther I, Hill K. The effect of water and sanitation on child health: evidence from the demographic and health surveys 1986-2007. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:1196-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gracey M. Child health in an urbanizing world. Acta Paediatr 2007;91:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aber JL, Bennett NG, Conley DC, Li J. The effects of poverty on child health and development. Annu Rev Public Health 1997;18:463-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gakidou E, Cowling K, Lozano R, Murray CJ. Increased educational attainment and its effect on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2010;376:959-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryce J, el Arifeen S, Pariyo G, Lanata C, Gwatkin D, Habicht J-P. Reducing child mortality: can public health deliver? Lancet 2003;362:159-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 2008;371:243-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newell M-L, Brahmbhatt H, Ghys PD. Child mortality and HIV infection in Africa: a review. AIDS 2004;18(Suppl 2):S27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health. Preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. WHO, 2011.

- 14.Lewis M. Governance and corruption in public health care systems. Working Paper No 78. Center for Global Development, 2006.

- 15.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley-Interscience, 2004.

- 16.Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Generalized additive models. Stat Sci 1986;1:297-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood AM, White IR, Royston P. How should variable selection be performed with multiply imputed data? Stat Med 2008;27:3227-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgenstern H. Ecologic studies in epidemiology: concepts, principles, and methods. Annu Rev Public Health 1995;16:61-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alkema L, You D. Child mortality estimation: a comparison of UN IGME and IHME estimates of levels and trends in under-five mortality rates and deaths. Byass P, ed. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Chew P, Magula N, DeVine D, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Report No 07-E007. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2007.

- 21.Collison D, Dey C, Hannah G, Stevenson L. Income inequality and child mortality in wealthy nations. J Public Health 2007;29:114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fewtrell L, Kaufmann RB, Kay D, Enanoria W, Haller L, Colford JM Jr. Water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhoea in less developed countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:42-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filmer D, Pritchett L. The impact of public spending on health: does money matter? Soc Sci Med 1999;49:1309-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Global HIV/AIDS response—epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access—progress report 2011. WHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF, 2011.

- 25.Adetunji J. Trends in under-5 mortality rates and the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:1200-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becquet R, Marston M, Dabis F, Moulton LH, Gray G, Coovadia HM, et al. Children who acquire HIV infection perinatally are at higher risk of early death than those acquiring infection through breastmilk: a meta-analysis. Bhutta ZA, ed. PLoS One 2012;7:e28510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bureau for Development Policy. Fighting corruption in the health sector: methods, tools and good practices. United Nations Development Programme, 2011.

- 28.Hanf M, Van-Melle A, Fraisse F, Roger A, Carme B, Nacher M. Corruption kills: estimating the global impact of corruption on children deaths. PLoS One 2011;6:e26990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muldoon KA, Galway LP, Nakajima M, Kanters S, Hogg RS, Bendavid E, et al. Health system determinants of infant, child and maternal mortality: a cross-sectional study of UN member countries. Global Health 2011;7:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta S, Davoodi HR, Tiongson E. Corruption and the provision of health care and education services. IMF working paper. International Monetary Fund, 2000.

- 31.Toole MJ, Galson S, Brady W. Are war and public health compatible? Lancet 1993;341:1193-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franco A. Effect of democracy on health: ecological study. BMJ 2004;329:1421-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary appendices