Abstract

Objective To compare perinatal outcomes in births of women with versus without a history of bariatric surgery.

Design Population based matched cohort study.

Setting Swedish national health service.

Participants 1 742 702 singleton births identified in the Swedish medical birth register between 1992 and 2009. For each birth to a mother with a history of bariatric surgery (n=2562), up to five control births were matched by maternal age, parity, early pregnancy body mass index, early pregnancy smoking status, educational level, and year of delivery. Secondary control cohorts, including women eligible for bariatric surgery (body mass index ≥35 or ≥40), were matched for the same factors except body mass index. History of maternal bariatric surgery was ascertained through the Swedish national patient register from 1980 to 2009.

Main outcome measures Preterm birth (<37 weeks), small for gestational age birth, large for gestational age birth, stillbirth (≥28 weeks), and neonatal death (0-27 days).

Results Post-surgery births were more often preterm than in matched controls (9.7% (243/2511) v 6.1% (750/12 379); odds ratio 1.7, 95% confidence interval 1.4 to 2.0; P<0.001). Body mass index seemed to be an effect modifier (P=0.01), and the increased risk of preterm birth was only observed in women with a body mass index <35. A history of bariatric surgery was associated with increased risks of both spontaneous (5.2% (130/2511) v 3.6% (441/12 379); odds ratio 1.5, 1.2 to 1.9; P<0.001) and medically indicated preterm birth (4.5% (113/2511) v 2.5% (309/12 379); odds ratio 1.8, 1.4 to 2.3; P<0.001). A history of bariatric surgery was also associated with an increased risk of a small for gestational age birth (5.2% (131/2507) v 3.0% (369/12 338); odds ratio 2.0, 1.5 to 2.5; P<0.001) and lower risk of a large for gestational age birth (4.2% (105/2507) v 7.3% (895/12 338); odds ratio 0.6, 0.4 to 0.7; P<0.001). No differences were detected for stillbirth or neonatal death. The increased risks for preterm and small for gestational age birth, as well as the decreased risk for large for gestational age birth, remained when post-surgery births were compared with births of women eligible for bariatric surgery.

Conclusion Women with a history of bariatric surgery were at increased risk of preterm and small for gestational age births and should be regarded as a risk group during pregnancy.

Introduction

In 2008 an estimated 0.5 billion people globally were obese (body mass index ≥30).1 Obesity has been estimated to shorten lifespan by 2-4 years, and a body mass index ≥40 to shorten lifespan by 8-10 years.2 Besides the negative health impact of obesity, it is a risk factor for adverse pregnancy and perinatal outcomes, such as pregnancy associated hypertensive disorders,3 gestational diabetes,4 preterm birth,5 6 macrosomia,7 and perinatal mortality.8

Given the health risks of obesity, weight reduction is imperative to improve maternal health, pregnancy, and perinatal outcomes.5 Bariatric surgery is currently the most effective method for substantial and sustained weight loss.9 10 Use of bariatric surgery has increased rapidly since the 1990s, also among women of reproductive age.11 In Sweden, the number of bariatric procedures increased approximately 10-fold from 2002 to 2011, and 70-80% of the procedures were carried out in women.12

In a systematic review, three controlled cohort studies were singled out as the most robust trials, and were reported to have found that pregnancies after bariatric surgery carried similar risks of preterm birth13 14 15 or fetal growth restriction13 14 to that of the general population or obese comparators (see supplementary figure 1). However, it has also been suggested that caloric restriction and nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery may adversely affect fetal growth.16 17 18 These findings originate from small studies with heterogeneous comparison groups. The systematic review of pregnancy and fertility after bariatric surgery concluded that rates of many adverse neonatal outcomes may be lower in women who become pregnant after bariatric surgery than in obese pregnant women, but that further data are needed.11

We carried out a population based matched cohort study using the nationwide Swedish medical birth register and national patient register to evaluate the association between bariatric surgery and perinatal outcomes.

Methods

Setting and participants

In Sweden, antenatal and delivery care is provided for free, with a participation rate in the antenatal care programme close to 100%. The first visit commonly takes place at the end of the first trimester.19

The Swedish medical birth register includes information on more than 98% of all births in Sweden since 1973. Starting at the first antenatal visit, information is prospectively collected, using standardised pregnancy, delivery, and infancy records.20

Between 1992 and 2009, 1 812 708 births were recorded in the medical birth register. We excluded all multiple births since they differ in duration of gestation and fetal growth, as well as having a higher occurrence of pregnancy and perinatal complications.21 Furthermore, we also excluded mothers without a valid personal identity number at the time of delivery, as they could not be linked to other register sources.

Register linkage

By using the unique personal identity number assigned to each Swedish resident, we linked data from the medical birth register to the national patient register and the education register. The national patient register includes information on hospital admissions, diagnoses, and surgical procedures. Diagnoses are coded according to the Swedish versions of the international classifications of diseases (ninth revision used between 1987 and 1996; 10th revision used thereafter). Surgical procedures were coded according to the Swedish version of the classification of surgical procedures (Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee; NOMESCO).

Covariates

From the medical birth register we retrieved data on maternal age, parity, early pregnancy body mass index, early pregnancy smoking status, delivery year, diabetes, and prepregnancy hypertension. We calculated body mass index from weight and height at the first antenatal visit and categorised the women as underweight (body mass index <18.5), of normal weight (18.5-24.9), overweight (25.0-29.9), or obesity class 1 (30.0-34.9), 2 (35.0-39.9), or 3 (≥40.0). At the same visit, smoking behaviours were registered, based on self reported cigarette consumption (non-smoker, 1-9 or ≥10 cigarettes daily). We retrieved information on maternal education level from the education register and categorised this as ≤9, 10-12, and >12 years of schooling.

Intervention cohort

From the national patient register we recorded the date of the first bariatric surgery procedure using the codes from the NOMESCO classification, and classified procedures into gastric bypass, vertical banded gastroplasty, and gastric banding (see supplementary table 1). We included women with one bariatric procedure as well as women with multiple procedures. We calculated the interval from surgery to delivery from the first procedure. The register included surgeries conducted in both the national healthcare system and private practices and was estimated to cover approximately 84% of all bariatric surgery procedures in Sweden in 2009.12

To minimise the risk of including women undergoing a gastric bypass or gastric resection for reasons other than obesity, we excluded those with a history of bariatric surgery but without a diagnosis code for obesity (see supplementary table 1). These women were not eligible as controls.

Control cohorts

Primary control group—We created a matched control cohort using births of women with no registered history of bariatric surgery. Control births were matched 5:1 with replacement by maternal age (one year either way), parity (nulliparous or parous), body mass index in early pregnancy (18.5-24.9, 25-29.9, 30-34.9, 35-39.9, ≥40, or missing), smoking status in early pregnancy (non-smoker, 1-9 or ≥10 cigarettes daily, or missing), educational level (≤9, 10-12, or >12 years of schooling, or missing), and delivery year (1992-2009). The purpose of this primary control group was to derive risk information on perinatal outcomes for pregnant women with a history of bariatric surgery compared with women with similar characteristics at the time of pregnancy, including body mass index.

Secondary control group (body mass index ≥35)—We used the same sampling procedure for a secondary control group, except that we dropped body mass index as a matching factor and controls were required to have an early pregnancy body mass index ≥35. In Sweden, the indication for bariatric surgery is currently a body mass index of ≥35, although some counties require ≥40 or ≥35 combined with obesity related comorbidity.22 We used this secondary control group to compare births of women with a history of bariatric surgery with births of women without such a history, but who were eligible for bariatric surgery. In this comparison, we estimated whether risks of adverse perinatal outcomes were different in women after bariatric surgery compared with fertile women eligible for bariatric surgery after accounting for age, parity, smoking status, education level, and delivery year.

Tertiary control group (body mass index ≥40)—We used the same sampling procedure as for the secondary control group, but control group women were required to have a body mass index ≥40 (the eligibility criteria for bariatric surgery in some counties). Also, we sampled only up to three controls per case as fewer women had a body mass index ≥40. The purpose of this group was the same as for the secondary control group.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were preterm birth, and birth weight for gestational age, which is commonly used as a proxy for fetal growth.

We defined preterm birth as <37 completed weeks of gestation, and we stratified this into moderately preterm birth (32-36 completed weeks) and very preterm birth (<32 completed weeks).23 Deliveries before 37 weeks of gestation were further divided into spontaneous and medically induced preterm birth. Gestational age was determined by ultrasonography, or, if unavailable, the recorded date of the first day of the last menstrual period. Since 1990, Swedish women are routinely offered ultrasonography early in the second trimester to estimate gestational age, and about 95% accept this offer.24

We used the current ultrasound based Swedish reference curves for fetal growth.25 Large for gestational age babies and small for gestational age babies were defined as a birth weight of more than 2 standard deviations above or below the mean for gestational age and sex, respectively. Supplementary table 2 presents the proportions of missing data on gestational age (0.1% (3/2534) in cases; 0.1% (16/12 468) in controls) and birth weight (0.3% (7/2534) in cases; 0.5% (57/12 468) in controls).

As secondary outcomes, we analysed stillbirth (fetal death at ≥28 completed gestational weeks26) and neonatal death (death of a liveborn infant within 0-27 days of life). Analyses of preterm birth, birth weight for gestational age, and neonatal mortality excluded stillbirths.

Statistical analysis

We compared singleton births of women with a registered history of bariatric surgery with matched control births of women without such a history.

Main analysis—Using logistic regression conditioning on the matching factors, we estimated odds ratios for the outcomes for post-surgery births versus matched control births. Additionally, we estimated risk differences. Potential interactions between the matching factors were handled by conditioning the analyses on these factors.

Subgroup analysis—We repeated the main analysis in prespecified subgroups for surgical procedure (gastric banding, gastric bypass, vertical banded gastroplasty), body mass index category (<30, 30-34.9, or ≥35), and interval from surgery to delivery (<2, 2-5, >5 years; the lower boundary chosen to coincide with the recommendation from some authors not to become pregnant within the first 24 months after bariatric surgery13). In exploratory analyses we also repeated the analyses by parity (nulliparous or parous).

Sensitivity analysis—In addition to the conditional logistic regression, we estimated odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals using a generalised estimation equation framework. Thereby we estimated confidence intervals after accounting for women who contributed more than one birth.

We analysed data using SAS version 9.3. Reported P values are two sided and we considered values <0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

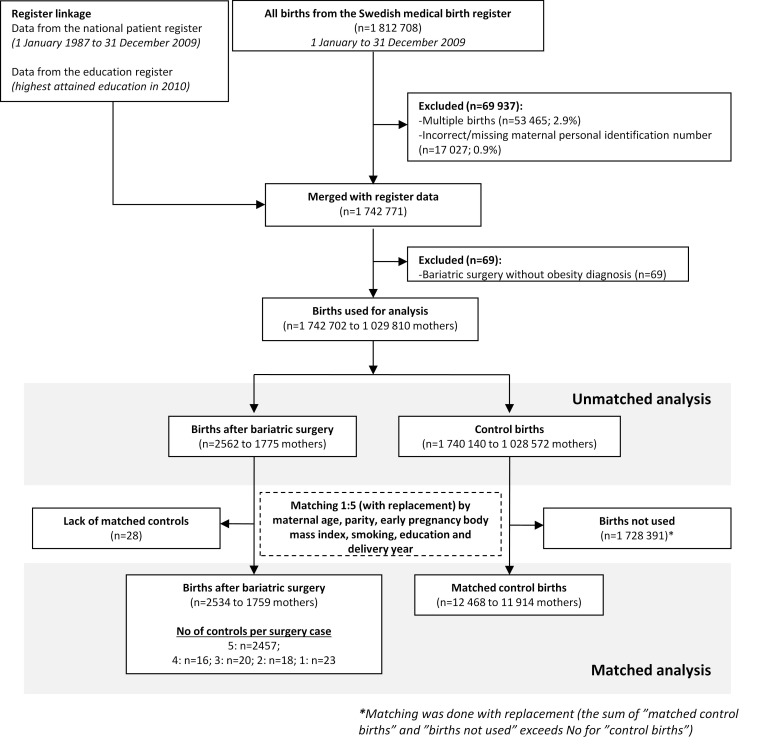

In the Swedish medical birth register 1 812 708 births were registered between 1992 and 2009. Mothers without a valid personal identity number at the time of delivery (0.9%, n=17 027/1 812 708), with multiple births (2.9%, n=53 465/1 812 708), or with a registered history of bariatric surgery but without an obesity diagnosis were excluded (0.004%, n=69/1 742 771; fig 1). After these exclusions 1 742 702 births remained, with 2562 occurring after bariatric surgery.

Fig 1 Flow chart showing identification of study population from Swedish medical birth register and national patient register

Procedure and maternal characteristics

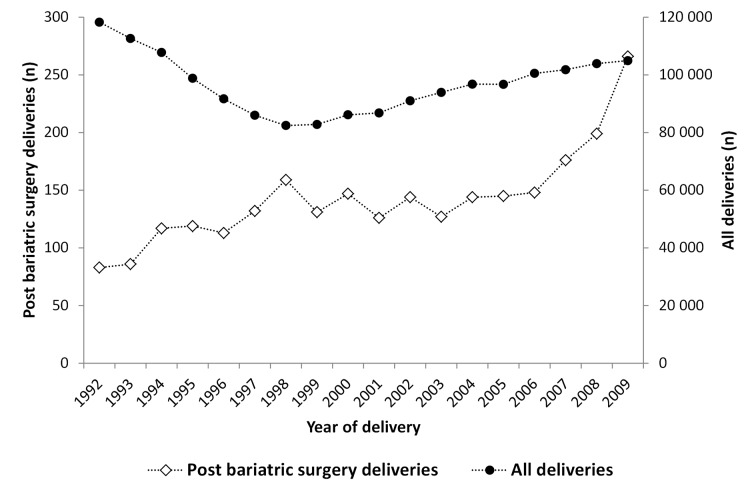

From 1992 to 2009 the annual number of singleton births of women with a registered history of bariatric surgery increased from 83 to 266 (P<0.001; fig 2). Vertical banded gastroplasty was the most common procedure, followed by gastric bypass and gastric banding (table 1). The preference for procedure changed over time: 18% (15/83) of the post-surgery births in 1992 were after gastric bypass compared with 75% in 2009 (200/266). The mean interval between surgery and delivery was 5.2 years (SD 3.7; median 4.2; 25th to 75th centile 2.4 to 7.2; minimum to maximum 0.4 to 24.5 years).

Fig 2 Singleton births in Sweden between 1992 and 2009 to women with and without a registered history of bariatric surgery for obesity

Table 1.

Characteristics of mothers to singleton births in Sweden between 1992 and 2009 (before matching)

| Characteristics | No (%) of births | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bariatric surgery (n=2562) | No bariatric surgery (n=1 740 140) | ||

| Type of procedure: | |||

| Vertical banded gastroplasty | 964 (38) | — | — |

| Gastric bypass | 833 (33) | — | — |

| Gastric banding | 698 (27) | — | — |

| Other | 67 (2.6) | ||

| Surgery to delivery interval (years): | |||

| <1 | 61 (2.4) | — | — |

| 1-1.9 | 422 (16) | — | — |

| 2-4.9 | 1001 (39) | — | — |

| ≥5 | 1078 (42) | — | — |

| Multiple bariatric procedures | 586 (23) | — | — |

| Maternal age (years): | |||

| 13-24 | 144 (6) | 296 327 (17) | <0.001 |

| 25-29 | 639 (25) | 581 952 (33) | |

| 30-34 | 942 (37) | 565 113 (32) | |

| ≥35 | 837 (33) | 296 726 (17) | |

| Early pregnancy body mass index: | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 3 (0.12) | 40 199 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Normal weight (18.5-24.9) | 184 (7.2) | 959 344 (55) | |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 640 (25) | 349 596 (20) | |

| Obesity class 1 (30-34.9) | 697 (27) | 103 922 (6.0) | |

| Obesity class 2 (35-39.9) | 437 (17) | 29 350 (1.7) | |

| Obesity class 3 (≥40) | 248 (9.7) | 9515 (0.55) | |

| Missing | 353 (14) | 248 214 (14) | |

| Early pregnancy smoking status: | |||

| Non-smoking | 1663 (65) | 1 438 093 (83) | <0.001 |

| 1-9 cigarettes/day | 418 (16) | 140 694 (8.1) | |

| ≥10 cigarettes/day | 323 (13) | 66 698 (3.8) | |

| Missing | 158 (6.2) | 94 655 (5.4) | |

| Educational level (years): | |||

| ≤9 | 423 (17) | 164 805 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| 10-12 | 1630 (64) | 772 616 (44) | |

| >12 | 461 (18) | 754 820 (43) | |

| Missing | 48 (1.9) | 47 899 (2.8) | |

| Nulliparous | 763 (30) | 748 279 (43) | <0.001 |

| Prepregnancy hypertension | 61 (2.4) | 7369 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Prepregnancy diabetes | 25 (1.0) | 10 744 (0.4) | <0.001 |

Compared with women with no registered history of bariatric surgery, women with such a history were older, more often obese, had a lower education, and were more often smokers and parous (all P<0.001; table 1). The matching procedure eliminated these differences, where matched control births were identified for all but 1.1% (28/2562) of the births after bariatric surgery. This left 2534 births after bariatric surgery to be compared with 12 468 matched control births of women of similar age, parity, early pregnancy body mass index, early pregnancy smoking status, educational level, and delivery year (fig 1).

Preterm birth

Preterm birth was observed in 9.7% (243/2511) of post-surgery births versus 6.1% (750/12 379) in matched controls (risk difference 3.6%, 95% confidence interval 2.4% to 4.9%; P<0.001; table 2 and supplementary figure 2). The risks were increased for both medically indicated and spontaneous preterm births (table 2).

Table 2.

Preterm birth and fetal growth outcomes for births of women with a history of bariatric surgery and matched controls*

| Outcome | No of births | No (%) of cases† | Bariatric surgery v matched controls | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk difference (95% CI) | Conditional odds ratio (95% CI)‡ | ||||||||

| Bariatric surgery | Matched controls | Bariatric surgery | Matched controls | ||||||

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | 2511 | 12 379 | 243 (9.7) | 750 (6.1) | 3.6 (2.4 to 4.9) | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.0) | P<0.001 | ||

| Medically indicated preterm birth | 2511 | 12 379 | 113 (4.5) | 309 (2.5) | 2.0 (1.2 to 2.9) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.3) | P<0.001 | ||

| Spontaneous preterm birth | 2511 | 12 379 | 130 (5.2) | 441 (3.6) | 1.6 (0.7 to 2.5) | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) | P<0.001 | ||

| Moderately preterm (32-36 weeks) | 2456 | 12 250 | 188 (7.7) | 621 (5.1) | 2.6 (1.5 to 3.7) | 1.6 (1.3 to 1.9) | P<0.001 | ||

| Very preterm (<32 weeks) | 2511 | 12 379 | 55 (2.2) | 129 (1.0) | 1.2 (0.6 to 1.8) | 2.0 (1.4 to 2.9) | P<0.001 | ||

| Fetal growth: | |||||||||

| Small for gestational age | 2507 | 12 338 | 131 (5.2) | 369 (3.0) | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.2) | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.5) | P<0.001 | ||

| Large for gestational age | 2507 | 12 338 | 105 (4.2) | 895 (7.3) | −3.1 (−4.0 to −2.2) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.7) | P<0.001 | ||

*Live singleton births of women with a history of bariatric surgery matched 1:5 (with replacement) to births of women without a history of bariatric surgery, using maternal age, parity, early pregnancy body mass index, early pregnancy smoking status, educational level, and year of delivery as matching factors.

†Analyses of preterm birth exclude infants with missing gestational age (0.1%), and analyses of moderately preterm birth also exclude very preterm births. Analyses of fetal growth exclude births without data on birth weight or gestational age (0.3-0.5%; see supplementary table 2).

‡Conditioned on matching factors (maternal age, parity, early pregnancy body mass index, early pregnancy smoking status, educational level, and year of delivery).

The risks of moderately and very preterm birth were also higher in post-surgery births than in control births (table 2). In the sensitivity analysis, where we accounted for the fact that the same woman could give birth more than once, the confidence interval for the odds ratio for preterm birth was similar to that in the main analysis (odds ratio 1.7, 95% confidence interval 1.4 to 2.0; P<0.001).

Fetal growth

The risk of delivering a small for gestational age infant was higher in women with a history of bariatric surgery than in matched controls (5.2% (131/2507) v 3.0% (369/12 338); risk difference 2.2%, 95% confidence interval 1.3% to 3.2%; P<0.001; table 2). The opposite was the case for large for gestational age births (table 2).

Subgroup analysis

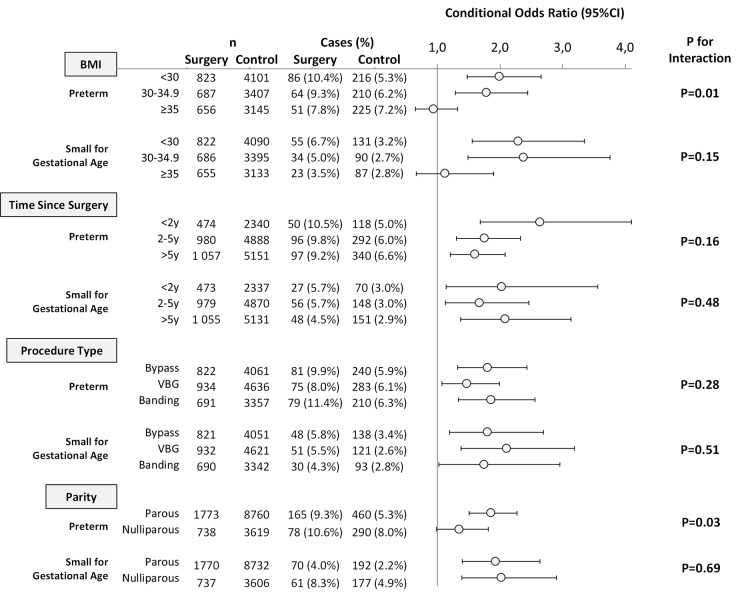

Body mass index—For preterm birth, data suggested effect modification by early pregnancy body mass index (P=0.01). Compared with matched controls with a similar body mass index, the highest risk of preterm birth was observed in women with a history of bariatric surgery and an early pregnancy body mass index <30, followed by body mass index 30-34.9, whereas no increased risk was seen in women with a body mass index ≥35 (fig 3). No effect modification was detected for fetal growth outcomes, although the gradient was in the same direction as for preterm birth, and no increased risk for small for gestational age birth was seen among births of women with an early pregnancy body mass index ≥35.

Fig 3 Conditional odds ratios for preterm birth and fetal growth by early pregnancy body mass index, interval between surgery and delivery, surgery type, and parity. Odds ratios conditioned on matching factors: maternal age, parity, early pregnancy body mass index, early pregnancy smoking status, educational level, and year of delivery

Procedure type and surgery to delivery interval—No effect modification by procedure type or interval between surgery and delivery was detected for preterm or small for gestational age birth (fig 3).

Parity—Effect modification by parity was observed for preterm birth, with an increase in risk only among parous women with a history of bariatric surgery, whereas the risk increase was borderline for the smaller group of nulliparous women (fig 3).

Mortality

No differences between post-bariatric surgery and matched control births were detected for stillbirth (0.79% (20/2534) v 0.60% (75/12 468); risk difference 0.19%, 95% confidence interval −0.18% to 0.56%; P=0.32) or neonatal death (0.28% (7/2514) v 0.26% (32/12 393); risk difference 0.02%, −0.20% to 0.24%; P=0.86; see supplementary table 3).

Comparison with women eligible for bariatric surgery

When comparing post-bariatric surgery births with matched control births of women who were eligible for bariatric surgery (body mass index ≥35; n=2496:12 126; mean body mass index 32.5 v 38.5; P<0.001), the excess risk of preterm birth observed in the main analysis was attenuated but remained increased (9.5% (236/2474) v 7.2% (863/12 027); risk difference 2.4%, 1.1% to 3.6%; P<0.001). The risk difference for small for gestational age birth increased (5.2% (128/2470) v 2.6% (313/11 979); risk difference 2.6%, 1.7% to 3.5%; P<0.001).

When using the stricter criterion of body mass index ≥40 for the control group and matching up to three controls per case (n=2392:6818; mean body mass index 32.5 v 43.2; P<0.001), the excess risk of preterm birth was further attenuated but remained higher in post-bariatric surgery births (9.4% (224/2371) v 7.5% (508/6758); risk difference 1.9%, 0.6% to 3.3%; P=0.03). The risk difference for small for gestational age birth did not change (5.0% (118/2367) v 2.5% (168/6714); risk difference 2.5%, 1.5% to 3.4%; P<0.001).

Discussion

This nationwide matched cohort study found an increased risk of preterm and small for gestational age births but lower risk of large for gestational age births in women with a registered history of bariatric surgery compared with women with similar characteristics but without a history of bariatric surgery. This could not be attributed to differences in maternal age, parity, early pregnancy body mass index, smoking, or educational level, which were used as matching factors. Data suggested that the increased risks of preterm and small for gestational age births were confined to the comparison of women with an early pregnancy body mass index <35.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

The main strength of this study was its large sample size, providing sufficient power to detect associations between a history of bariatric surgery and several perinatal outcomes, overall as well as in subgroups defined by early pregnancy body mass index. Furthermore, the study was nationwide and population based, with about 95% of the pregnancies dated using ultrasonography. Because we used the ultrasound based Swedish reference curve for fetal growth, misclassification of gestational age and fetal growth was minimised. In addition, outcome data were registered prospectively, eliminating recall bias.

One limitation was the lack of information on presurgery weight and weight loss from surgery to pregnancy. The risk of preterm birth may have been even higher before surgery and the subsequent weight loss, as this risk increases with increasing severity of obesity.6 We did not test the presurgery versus post-surgery risks of preterm birth. However, the increased risk remained when post-bariatric surgery births were compared with births of women with early pregnancy body mass index above commonly applied eligibility thresholds for bariatric surgery (≥35 and ≥40). The risk of small for gestational age birth is unlikely to have been higher before surgery, as body mass index is positively correlated with birth weight, and comparisons with births of women with an early pregnancy body mass index ≥35 or ≥40 only increased the risk difference.

Another limitation was that we did not capture all bariatric procedures. In 2009, the national patient register covered an estimated 84% of bariatric procedures in Sweden.12 Given the low number of pregnant women with a history of bariatric surgery, the extent of any exposure misclassification is likely to be small. Also, since misclassification of bariatric surgery is unlikely to be associated with pregnancy outcomes, it would bias the results towards the null.

Between 1992 and 2009 the preferred bariatric procedure changed from mainly vertical banded gastroplasty to gastric bypass. We did not detect any effect modification by procedure type, but procedures performed at the beginning of the period had more time to reach a steady state in weight reduction, which may influence outcomes. Also, our results may not be generalisable to other types of procedures.

Finally, despite the large sample size, the number of stillbirths and neonatal deaths was low, resulting in limited statistical power. However, observed between group differences were small and the upper confidence limits suggest that more than doubled risks can be excluded.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

In a systematic review of pregnancy and fertility after bariatric surgery,11 three cohort studies using consecutive patients matched for one or more characteristics were highlighted as the most rigorous. Two of these studies reported a similar risk of preterm birth to the general population,13 14 and one showed a similar risk compared with obese comparators.15 Two recent Scandinavian studies likewise did not detect any difference in preterm birth between post-bariatric surgery and control births.16 18 These studies had limited statistical power, including a maximum of 29 preterm births in the bariatric surgery group (compared with 243 in our study). We found an increased risk of preterm birth after bariatric surgery, irrespective of procedure type, and compared with body mass index matched controls as well as women eligible for bariatric surgery. This may be explained by the greater statistical power in our study, as point estimates in previous studies have been in the same direction (see supplementary figure 1),13 14 15 16 18 and one study did detect a statistically significant difference.17 Our subgroup analyses indicated that the increased risk of preterm birth was confined to the comparison of women with an early pregnancy body mass index <35.

Concerns exist about micronutrient deficiencies in women after bariatric surgery, which may affect both fetal and placental growth.27 The literature is ambiguous on the risk of intrauterine growth restriction in women after bariatric surgery.11 Opposite to our finding, one study reported low birth weight to be less common in obese women with a history of bariatric surgery than in obese women without such a history,15 whereas another study reported no difference in the proportion of infants less than the 10th centile of birth weight in women who had had gastric bypass compared with age matched and caesarean section matched controls,14 and yet another study detected no differences compared with obese controls.13 Three recent studies from the United States and Scandinavia support our findings of a greater risk of small for gestational age birth after bariatric surgery.16 17 18

Excessive fetal growth is strongly associated with obesity and often co-existing insulin resistance leading to hyperglycaemia.28 Bariatric surgery improves glucose control in obese people with type 2 diabetes.10 Several studies on women with a history of bariatric surgery report a decreased proportion of macrosomic or large for gestational age infants,11 15 17 similar to our findings, although a previous Swedish study did not find any difference.16

Meaning of the study

Pregnant women with a history of bariatric surgery should be regarded as a risk group and be counselled about the increased risk of preterm birth and intrauterine growth restriction compared with pregnant women with similar characteristics. It should also be noted that no difference in preterm birth or small for gestational age birth was seen among women with versus without a history of bariatric surgery and an early pregnancy body mass index ≥35. Women with a history of bariatric surgery also had a decreased risk of large for gestational age birth.

Unanswered questions and future research

Our study did not investigate whether the increased risk for small for gestational age birth was caused by micronutrient deficiencies,27 nor if it can be reduced by more intensive micronutrient or fetal growth monitoring. The mechanism behind the observed effect modification by body mass index also needs further exploration, as no excess risks were observed for preterm or for small for gestational age birth in women who were morbidly obese.

What is already known on this topic

Obesity is a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth, excessive fetal growth, and stillbirth

Bariatric surgery results in large and sustained weight loss and is common among women of reproductive age

Small studies have generally failed to detect differences in preterm birth outcomes between women with a history of bariatric surgery and obese comparators, or even the general population, and have shown conflicting results about fetal growth

What this study adds

Women with a history of bariatric surgery were found to have increased risks of preterm and small for gestational age births but a decreased risk of large for gestational age birth

The increased risks of preterm and small for gestational age births were confined to births of women with an early pregnancy body mass index below 35

Contributors: MN and NR contributed equally to this paper and share first authorship. They drafted the manuscript and carried out the statistical analysis. All authors analysed and interpreted the data, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and contributed to and approved the final version. They are the guarantors. SC, FG, MN, NR, and OS conceived and designed the study. OS acquired the data, provided administrative, technical, and material support, and supervised the study. MN and NR had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis as well as the final decision to submit for publication.

Funding: This study did not receive any specific funding.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare that SC was supported by a distinguished professor award (Karolinska Institutet); MN was supported by the strategic young scholar award in epidemiology (Karolinska Institutet); NR was supported by the board of postgraduate education at the Karolinska Institutet (Karolinska Institutet Doctoral Student Financing Fund); OS was supported by the Swedish Society of Medicine and the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet; and that SC, NR, MS, and YT-L have had no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years. MN has received lecture or consulting fees from Abbott, Sanofi-Aventis, Itrim International, and Strategic Health Resources; research grants from Cambridge Weight Plan and Novo Nordisk; and royalty payments for co-authoring chapters in a Swedish textbook on obesity. The authors declare that they have no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the regional ethics committee at the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The lead author affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;347:f6460

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary information

References

- 1.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 2011;377:557-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 2009;373:1083-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh SW. Obesity: a risk factor for preeclampsia. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2007;18:365-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh J, Huang CC, Driggers RW, Timofeev J, Amini D, Landy HJ, et al. The impact of pre-pregnancy body mass index on the risk of gestational diabetes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25:5-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cnattingius S, Bergstrom R, Lipworth L, Kramer MS. Prepregnancy weight and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 1998;338:147-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cnattingius S, Villamor E, Johansson S, Edstedt Bonamy AK, Persson M, Wikstrom AK, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of preterm delivery. JAMA 2013;309:2362-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surkan PJ, Hsieh CC, Johansson AL, Dickman PW, Cnattingius S. Reasons for increasing trends in large for gestational age births. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:720-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephansson O, Dickman PW, Johansson A, Cnattingius S. Maternal weight, pregnancy weight gain, and the risk of antepartum stillbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004;292:1724-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2683-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maggard MA, Yermilov I, Li Z, Maglione M, Newberry S, Suttorp M, et al. Pregnancy and fertility following bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA 2008;300:2286-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.SOREG. Annual Report SOReg 2011. Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Register [In Swedish], 2012.

- 13.Patel JA, Patel NA, Thomas RL, Nelms JK, Colella JJ. Pregnancy outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2008;4:39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wax JR, Cartin A, Wolff R, Lepich S, Pinette MG, Blackstone J. Pregnancy following gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity: maternal and neonatal outcomes. Obes Surg 2008;18:540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ducarme G, Revaux A, Rodrigues A, Aissaoui F, Pharisien I, Uzan M. Obstetric outcome following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Int J Gynaecol Obstetr 2007;98:244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Josefsson A, Blomberg M, Bladh M, Frederiksen SG, Sydsjo G. Bariatric surgery in a national cohort of women: sociodemographics and obstetric outcomes. Am J Obstetr Gynecol 2011;205:206 e1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lesko J, Peaceman A. Pregnancy outcomes in women after bariatric surgery compared with obese and morbidly obese controls. Obstetr Gynecol 2012;119:547-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kjaer MM, Lauenborg J, Breum BM, Nilas L. The risk of adverse pregnancy outcome after bariatric surgery: a nationwide register-based matched cohort study. Am J Obstetr Gynecol 2013;208:464 e1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odlind V, Haglund B, Pakkanen M, Otterblad Olausson P. Deliveries, mothers and newborn infants in Sweden, 1973-2000. Trends in obstetrics as reported to the Swedish Medical Birth Register. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2003;82:516-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cnattingius S, Ericson A, Gunnarskog J, Kallen B. A quality study of a medical birth registry. Scand J Soc Med 1990;18:143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao A, Sairam S, Shehata H. Obstetric complications of twin pregnancies. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2004;18:557-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SFÖAK. Proposal for national medical indications and quality requirements for producers of obesity surgery [In Swedish], 2011.

- 23.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371:75-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogberg U, Larsson N. Early dating by ultrasound and perinatal outcome. A cohort study. Acta Obstetr Gynecol Scand 1997;76:907-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marsal K, Persson PH, Larsen T, Lilja H, Selbing A, Sultan B. Intrauterine growth curves based on ultrasonically estimated foetal weights. Acta Paediatr 1996;85:843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Pattinson R, Cousens S, Kumar R, Ibiebele I, et al. Stillbirths: Where? When? Why? How to make the data count? Lancet 2011;377:1448-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao KR, Padmavathi IJ, Raghunath M. Maternal micronutrient restriction programs the body adiposity, adipocyte function and lipid metabolism in offspring: a review. Rev Endocr Metab Dis 2012;13:103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrenberg HM, Mercer BM, Catalano PM. The influence of obesity and diabetes on the prevalence of macrosomia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:964-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information