Abstract

The microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) is the “master melanocyte transcription factor” with a complex role in melanoma. MITF protein levels vary between and within clinical specimens, and amplifications and gain- and loss-of-function mutations have been identified in melanoma. How MITF functions in melanoma development and the effects of targeting MITF in vivo are unknown because MITF levels have not been directly tested in a genetic animal model. Here, we use a temperature-sensitive mitf zebrafish mutant to conditionally control endogenous MITF activity. We show that low levels of endogenous MITF activity are oncogenic with BRAFV600E to promote melanoma that reflects the pathology of the human disease. Remarkably, abrogating MITF activity in BRAFV600Emitf melanoma leads to dramatic tumor regression marked by melanophage infiltration and increased apoptosis. These studies are significant because they show that targeting MITF activity is a potent antitumor mechanism, but also show that caution is required because low levels of wild-type MITF activity are oncogenic.

INTRODUCTION

Driver genes that stimulate proliferation and survival are important drug targets in cancer. The discovery of BRAFV600E mutations in nevi and melanoma has directly led to the development of small-molecule inhibitors with clear clinical benefit (Flaherty et al., 2012). Despite these dramatic improvements, drug resistance remains a critical problem, and most patients with metastatic melanoma eventually succumb to the disease within a year. It is therefore necessary to identify additional therapeutic targets in melanoma that can be used in combination with available treatments (Tsao et al., 2012).

One of the important genes in melanocyte development and melanoma is the highly conserved “master melanocyte transcription factor” microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) (Levy et al., 2006). MITF responds to multiple signaling cascades to orchestrate genes involved in melanocyte growth, differentiation, and survival (Cheli et al., 2010). Although MITF mutations in development lead to similar phenotypes across species, the function of MITF in melanoma is complex and not fully understood. MITF is expressed in most melanomas, although MITF protein levels vary between melanoma specimens, with some subsets of melanoma showing high levels and others showing low levels of MITF (Flaherty et al., 2012). MITF activity can also vary within an individual melanoma, such that low levels of MITF promote invasion and stem-cell like phenotypes and moderate levels of MITF activity promote cell cycle progression (Goodall et al., 2008; Hoek and Goding, 2010; Cheli et al., 2011; Strub et al., 2011; Cheli et al., 2012). The ability of MITF to activate cancer hallmark genes makes it an important mediator of oncogenic signaling in cancer. This is underscored by evidence that MITF is at least partially responsible for the oncogenic potential of BRAF in cells (Wellbrock and Marais, 2005; Wellbrock et al., 2008). Studies from melanoma cells indicate that a key function of BRAFV600E seems to be to maintain MITF activity at a critical threshold where it promotes proliferation, invasion, and survival, without promoting differentiation (at higher levels) or apoptosis or senescence (at lower levels) (Giuliano et al., 2010; Hoek and Goding, 2010; Cheli et al., 2011; Strub et al., 2011; Cheli et al., 2012)

However, MITF may have additional cooperating functions in melanoma. MITF is amplified in some melanomas, and expression of ectopic MITF can cooperate with BRAFV600E to transform primary human melanocytes and neural crest cells (Garraway et al., 2005; Kumar et al., 2013). In addition, MITF mutations have been identified in BRAFV600E melanomas including somatic mutations with either hypomorphic or increased activity (Cronin et al., 2009), and a germline SUMOylation E318K mutation that is a melanoma risk factor and confers differential gene expression of MITF target genes (Bertolotto et al., 2011; Yokoyama et al., 2011). Thus, MITF is important in melanoma because it is an effector of oncogenic signaling, and also because it may have additional activity that contributes to melanomagenesis.

How MITF activity contributes to melanoma development and survival in an animal is unknown. Animal models are fundamental in establishing how genetic mutations contribute to cancer in vivo. Although many Mitf mutant mouse lines exist (Hou and Pavan, 2008), they do not permit conditional control of MITF activity in melanoma development or survival. Here, we address the importance of MITF activity in melanoma in vivo using a conditional mitfa temperature-sensitive zebrafish mutant (mitfavc7) in which endogenous MITF activity can be altered by changing the temperature of the water (Johnson et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2011). In zebrafish, there are two mitf genes (mitfa and mitfb), and mitfa is essential for the development of neural crest–derived melanocytes (Lister et al., 1999). Thus, by using a mitfa mutant we specifically control endogenous MITF activity in skin melanocytes, and avoid the potential complication of MITF activity in other tissues, such as those described in mouse mutants (Hou and Pavan, 2008). We show that low levels of wild-type MITF activity are oncogenic with BRAFV600E to promote melanoma in vivo, and that abrogating MITF activity in melanoma leads to rapid tumor regression. These results reveal that critical thresholds of MITF lead to dramatically different melanoma outcomes, and indicate that although targeting MITF activity is a potent antitumor approach, simply reducing MITF activity is sufficient to drive melanoma in BRAFV600E melanocytes.

RESULTS

Hypomorphic MITF is oncogenic with BRAFV600E in melanomagenesis

We sought to test whether hypomorphic levels of MITF activity could contribute to melanoma development in vivo using a zebrafish mitf temperature-sensitive mutant, mitfavc7 (Figure 1a–d; Johnson et al., 2011; originally characterized as fh53) and a transgenic line expressing BRAFV600E in melanocytes that we have previously developed and has been effective in the identification of cooperating driver genes (Figure 1e) (Patton et al., 2005; Ceol et al., 2011). The mitfavc7allele is a splice site mutation at the intron 6 splice donor site that leads to a reduction in melanocytes when zebrafish are reared at <26 °C, and an almost complete loss of melanocytes at >28 °C (Figure 1b–d) (Johnson et al., 2011). We performed two generations of genetic crosses with the BRAFV600E transgenic fish to the mitfavc7 mutant zebrafish to generate BRAFV600E/V600Emitfavc7/vc7 (BRAFV600Emitf) zebrafish. As expected, BRAFV600Emitf zebrafish did not develop melanocytes at the restrictive temperature (28.5 °C) because there is not sufficient MITF activity to generate melanocytes (Figure 1f). Importantly, at <26 °C, BRAFV600Emitf zebrafish developed nevi (Figure 1g), some of which progressed to melanoma (n=18/67; Figure 1h–j). The mitfavc7 allele is a splice site mutation, and we confirmed that the BRAFV600Emitf melanomas expressed the mis-spliced +intron6 variant with hypomorphic levels of correctly spliced mitfa (Figure 1k). As controls, neither BRAFV600E transgenic fish carrying wild-type mitfa alleles nor mitfa mutants lacking the BRAFV600E transgene developed melanoma at any temperature (Patton et al., 2005; Johnson et al., 2011; data not shown). We compared the incidence of melanoma in BRAFV600Emitf compared with BRAFV600E/V600Ep53M214K/M214K (BRAFV600Ep53) zebrafish, and found that the incidence was similar between the two genotypes (n=48/177; Figure 1j). These results show that hypomorphic levels of MITF activity interact genetically with BRAFV600E to promote melanoma in vivo.

Figure 1.

The microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) is oncogenic with BRAFV600E in melanomagenesis. (a) Adult wild-type zebrafish or (b) adult mitfavc7 mutant zebrafish living in water at 28 °C or (c, d) <26 °C. At <26 °C some melanocytes are visible in the body (d: enlarged region, white arrows). (e) Adult transgenic line expressing human BRAFV600E in the melanocytes. (f–i) Genetic crosses of BRAFV600Emitf at the semirestrictive temperatures develop nevi (*) and melanoma (on the tail of the middle fish, and on the head of the bottom fish). (j) Melanoma incidence curves of BRAFV600Ep53 and BRAFV600Emitf (<26 °C) genetic crosses. (k) Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of the mitfa transcript in BRAFV600Ep53 and BRAFV600Emitf melanomas.

BRAFV600Emitf melanomas display characteristic histopathological features

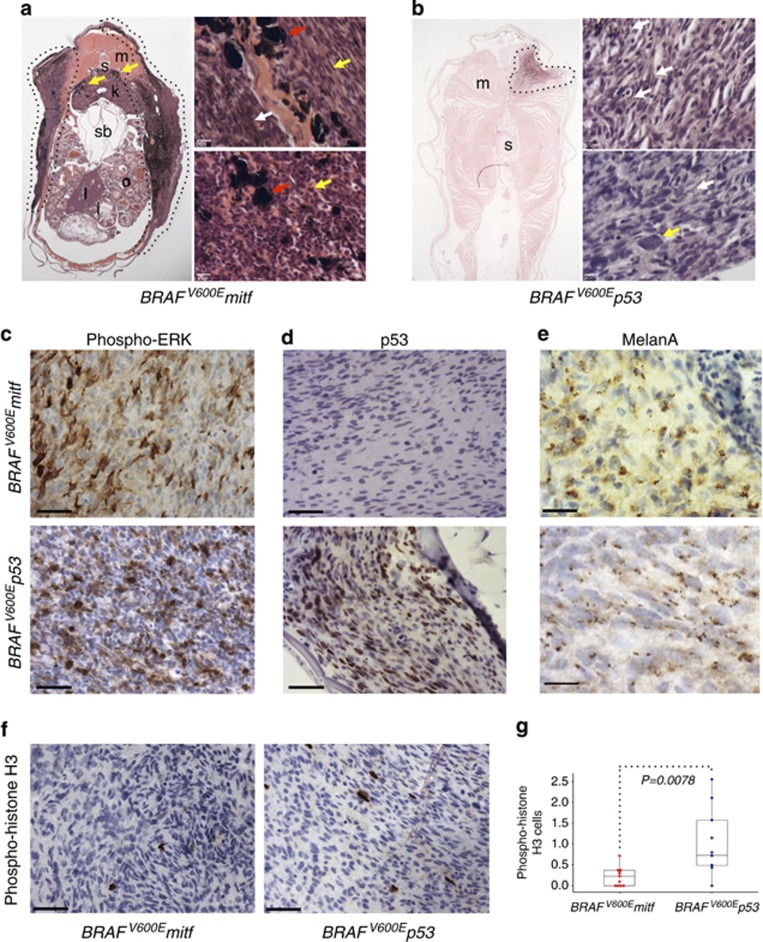

We wanted to know whether the mitf and p53 cooperating mutations contributed to melanoma pathology. We found that most BRAFV600Emitf melanomas displayed a superficial spreading growth pattern with some invasion into the underlying muscle (Figure 2a; n=22/26). This pattern was reminiscent of superficial spreading melanoma, the most common subtype of human melanoma. A striking characteristic feature of BRAFV600Emitf melanomas was the presence of large, heavily pigmented cells throughout the tumor (n=26/26), and often found in the kidney (the site of the hematopoietic compartment in zebrafish). Macrophages laden with melanin (melanophages) are often a feature of human malignant melanoma, and express CD68. We found these large cells to correspond to CD68-positive cells in the BRAFV600Emitf melanomas and characterized them as melanophages (Supplementary Figure S1 online). BRAFV600Emitf melanomas were composed of spindle- and epithelioid-shaped tumor cells, marked by few mitoses and showing only mild nuclear pleomorphism. These histological features were characteristic of BRAFV600Emitf melanomas, and allowed reliable identification of these tumors on blind assessment by a clinical skin pathologist (MEM; n=26/26; Figure 2a). By comparison, most BRAFV600Ep53 melanomas progressed rapidly, displaying a nodular and a highly invasive growth pattern into multiple organs (n=19/21; Figure 2b). No melanophages were observed in BRAFV600Ep53 melanomas, and the tumors were composed primarily of epithelioid cells, with features indicative of aggressive cancers including numerous mitoses and moderate-to-severe nuclear pleomorphism.

Figure 2.

Comparative histopathology of BRAFV600E melanomas. (a) Cross-section of adult BRAFV600Emitf zebrafish with superficial spreading melanoma (dotted line). Infiltrating melanophages in the kidney are indicated (yellow arrows). i, intestine; k, kidney; l, liver; m, muscle; o, ovary; s, spinal column; sb, swimbladder. (Top and bottom panels) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain of BRAFV600Emitf melanoma, indicating large melanophages (red arrows), spindle or epithelioid cell shapes (yellow arrows), and pigmented melanoma cells (white arrow). Scale bars=20 μm. (b) Cross-section of adult BRAFV600Ep53 zebrafish with invasive melanoma (dotted line). (Top and bottom panels) H&E stain of BRAFV600Ep53 melanoma, indicating pigmented melanoma cells (white arrows) and nuclear pleomorphisms (yellow arrow). Scale bars=20 μm. (c–f) Immunohistochemistry staining for (c) phospho-extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK), (d) p53, (e) Melan-A, and (f) phospho-histone H3. Scale bars=50 μm. (g). Box plot of mean percentage phospho-histone H3–stained cells in BRAFV600Emitf and BRAFV600Ep53 tumors (n=11 melanomas of each genotype). Bars represent interquartile range; Student's t-test P=0.0078.

We analyzed the activation state of the MAPK cascade in the BRAFV600Emitf and BRAFV600Ep53 mutant melanoma by performing immunohistochemical analysis with anti-phospho-extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK; Figure 2c). As expected, phospho-ERK signal was detected in the majority of melanoma cells in both BRAFV600Emitf and BRAFV600Ep53 melanoma, and BRAFV600Ep53 had increased levels of p53 mutant protein (Figure 2d). Both melanomas stained positively for Melan-A, a MITF target gene and marker for melanoma and melanocytes in human specimens (Du et al., 2003) (Figure 2e). Increased mitotic activity in BRAFV600Ep53 melanomas compared with BRAFV600Emitf melanoma cells was confirmed by immunostaining for phospho-histone H3, a marker of late-G2/M phase (Figure 2f and g). These results show that there is a strong genotype–phenotype correlation for cooperating mutations that can directly affect growth features and cellular histology.

Differential MITF target gene expression between melanoma genotypes

We wanted to understand how hypomorphic MITF activity contributed to melanoma, and hypothesized that MITF target genes may be differentially expressed between the melanoma genotypes. We performed quantitative real-time PCR on MITF target genes involved in proliferation (cdk2), cell cycle arrest (p16, p21), differentiation (tyr, dct), and survival (bcl-2, hif1α, c-met) (Figure 3). Despite the differences in phospho-histone H3 staining between the genotypes, the differences in cdk2, p16, and p21 cycle threshold (Ct) values between melanoma genotypes were not statistically significant (Figure 3a–c). Neither was there a significant difference in the cycle threshold values for expression of p53, bcl-2, or hif1α between melanoma genotypes (Figure 3f–h). These results indicate that despite the reduced levels of MITF activity in BRAFV600Emitf melanomas, there is sufficient MITF activity to control MITF target genes involved in cell proliferation and survival. Strikingly, BRAFV600Emitf melanomas expressed lower levels of differentiation genes (tyr and dct), as indicated by higher cycle threshold values (Figure 3d and e). Unexpectedly, we found that BRAFV600Emitf melanomas expressed significantly higher levels of c-met compared with BRAFV600Ep53 melanoma (Figure 3i). c-met is a MITF target gene, but is also transcriptionally regulated by Pax3 in melanoblasts and melanomas (McGill et al., 2006; Beuret et al., 2007; Mascarenhas et al., 2010). The tumor-initiating potential of cell types can vary within a lineage and differing tumor potentials may exist within the melanocyte lineage (Kumar et al., 2013). Although the tumors are heterogeneous, the low expression of differentiation genes (tyr and dct) coupled with high c-met gene expression pattern suggests that hypomorphic MITF activity may maintain melanocytes in a less differentiated state that is more susceptible to BRAFV600E transformation.

Figure 3.

MITF target gene expression. (a–i) Box plots of quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) of MITF target genes and p53. The y-axis indicates the difference between the cycle threshold (Ct) value of the gene of interest and the Ct value of β-actin in each sample. Note that the y-axis is inverted for ease of interpretation. Bars represent interquartile range; P-values determined by Student's t-test. Also see Supplementary Table S1 online. MITF, microphtholmia associated transcription factor.

Loss of MITF causes melanoma regression

MITF is a lineage survival oncogene in cells, but the effect of abrogating MITF activity in an animal model of melanoma in vivo is unknown. To develop an animal system that could directly validate MITF as a drug target, we tested the effects of dramatically reducing MITF activity on melanoma survival by increasing the water temperature to the restrictive conditions (32 °C); none of the aberrant mitfavc7 splice products are sufficient for melanocyte development at these restrictive temperatures (Johnson et al., 2011), and MITF activity is not required to maintain the activity of the mitfa promoter fragment driving the BRAFV600E transgene (Supplementary Figure S2 online; Dooley et al., 2013). BRAFV600Emitfvc7 zebrafish were reared at <26 °C to promote melanoma development, and then the temperature of the water was raised to 32 °C to turn off MITF activity. Within 2 weeks, 8/12 melanomas had dramatically regressed (Figure 4a; fish 1 and 2). Melanoma regression was the result of the mitfavc7 mutation and not just the water temperature because BRAFV600Ep53 zebrafish upshifted to 32 °C for 2 weeks showed no tumor regression and even continued growth (n=6/6; Figure 4b). By 2 months, 12/15 very large tumors showed regression, and 6 of these fish showed complete regression and even healing at the tumor site (Figure 4c; fish 3 and 4). Interestingly, despite the striking levels of melanoma regression, melanomas recurred following a temperature shift to <26 °C, indicating that a subpopulation of melanoma cells with very low MITF activity survive and are capable of repopulating the tumor site (Supplementary Figure S3 online).

Figure 4.

Abrogation of MITF activity causes melanoma regression. (a) Images of adult BRAFV600Emitf zebrafish at <26 °C, and transferred to water at 32 °C for 14 days (bottom images). Red dotted lines outline the tumors before and after the temperature shift. (b) Control BRAFV600Ep53 melanoma fish at <26 °C and at 32 °C. Areas of increased tumor growth are indicated with yellow asterisks. (c) Adult BRAFV600Emitf zebrafish at <26 °C and after 2 months at 32 °C. MITF, microphtholmia associated transcription factor.

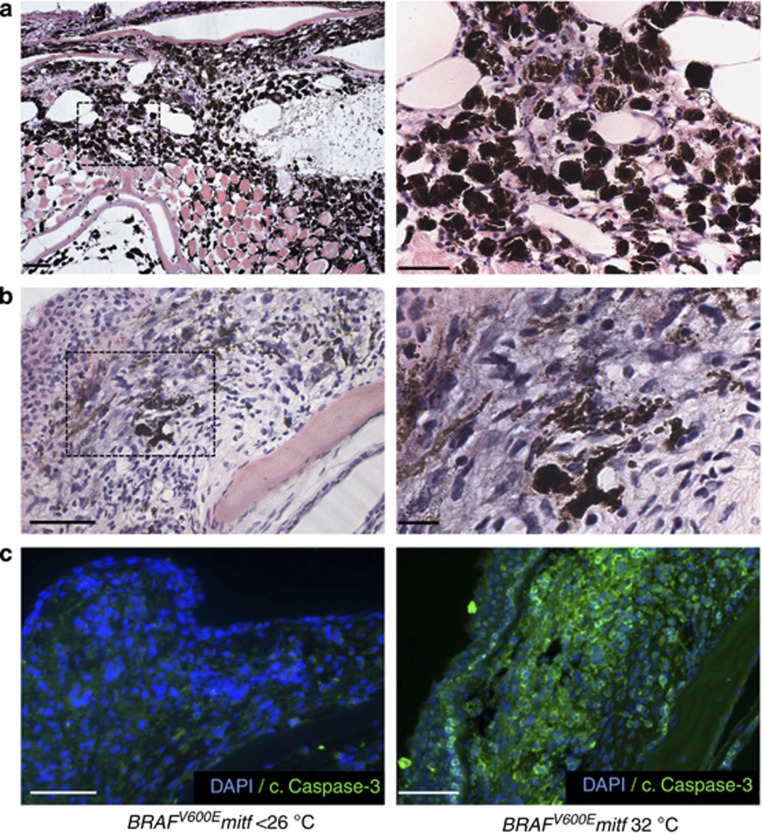

To understand the process of melanoma regression, we shifted BRAFV600Emitf zebrafish to the restrictive temperature (32 °C) for 7 days to analyze melanoma regression in progress. Histological analysis of the regressing melanomas showed evidence of tumor regression, characterized by marked loss of tumor cell density and accumulation of heavily pigmented melanophages (n=7/7; Figure 5a and b). To address whether apoptosis contributed to regression, we stained sections of the regressing BRAFV600Emitf melanomas with antibodies to detect active (cleaved) Caspase-3. We found high levels of active Caspase-3 in the regressing tumors compared with BRAFV600Emitf melanomas at <26 °C (n=5 in each group; Figure 5c). We conclude that there is a genetic dependency on MITF activity in BRAFV600Emitf melanoma.

Figure 5.

Melanoma regression is associated with melanophage and apoptotic activity. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of a regressing BRAFV600Emitf melanoma showing almost total regression with prominent melanophages (scale bar=200 μm). Boxed region is enlarged in right panel (scale bar=100 μm). (b) A regressing tumor, showing subtotal regression with melanoma cells present (scale bar=100 μm). Boxed region is enlarged in right panel (scale bar=50 μm). (c) Images of nonregressing (<26 °C) and regressing (32 °C) BRAFV600Emitf melanomas (as shown in b), stained with an antibody to detect cleaved-Caspase-3 (scale bar=50 μm).

DISCUSSION

Identifying BRAFV600E cooperating mutations that drive melanoma progression is critical for developing new therapeutic approaches and tackling drug resistance. Accumulating evidence indicates that MITF activity is a key contributing factor in melanoma (Tsao et al., 2012). We now show in an animal that a low level of wild-type MITF activity is oncogenic with BRAFV600E and that abrogating MITF activity in melanoma leads to tumor regression.

The BRAFV600Emitf model is relevant to human melanoma, because for some patients, low expression of MITF is associated with disease progression and poor prognosis (Salti et al., 2000; Levy et al., 2006). In these contexts, exogenous expression of MITF leads to inhibition of proliferation (Selzer et al., 2002; Wellbrock and Marais, 2005). This is in apparent contrast to evidence that MITF amplification is also an indicator of poor prognosis, and that MITF cooperates with BRAFV600E to transform melanocytes (Garraway et al., 2005). These differences in MITF activity may reflect distinct subtypes of melanoma; however, another possibility is that MITF amplification indicates the need for melanoma cells to maintain sufficient MITF activity for survival in the context of high BRAFV600E signaling (Garraway et al., 2005; Wellbrock et al., 2008). Thus, a common feature of melanoma may involve maintaining sufficient MITF activity for survival and proliferation while at the same time restricting higher levels of MITF activity that promote cell cycle arrest and differentiation or lower levels that lead to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Gray-Schopfer et al., 2007; Hoek and Goding, 2010). Here, the temperature-sensitive nature of the zebrafish mitfavc7 mutant allele enables MITF activity to be varied within an individual animal by altering the water temperature, thereby revealing the role of MITF activity levels in melanomagenesis and survival in vivo, although we cannot exclude the possibility that the mitfavc7 mutant has additional functions that contribute to melanoma.

Histopathological characteristics of melanoma are determined by a number of factors, and at least some are genetically determined (Whiteman et al., 2011). This is illustrated by the clinical classification of BRAFV600E melanomas as a subgroup based on histomorphological features (Viros et al., 2008). We show here that cooperating mutations also have an important role in determining the pathological features of melanoma. We find that low, oncogenic levels of MITF activity contribute to melanoma pathology, possibly by maintaining melanoma cells in a progenitor-like state. Notably, macrophages laden with melanin (melanophages) were a diagnostic feature of the BRAFV600Emitf melanomas. Melanophages are found in human melanomas, are indicative of an immune response, and predict an improved prognosis for patients, possibly because of tumor regression through macrophage engulfment of melanoma cells (Handerson et al., 2007). Thus, BRAFV600E cooperating mutations can directly influence tumor morphology, as well as tumor–immune cell interactions.

The dramatic recurrence of melanomas in patients following treatment with the BRAFV600E inhibitor, vemurafenib, indicates that combination therapies that target multiple pathways in melanoma may be necessary to improve patient outcome. MITF activity has been implicated as an important drug target (Flaherty et al., 2012; Tsao et al., 2012), and we now show that shutting off endogenous MITF activity in vivo leads to dramatic and rapid melanoma regression, characterized by melanophage infiltration and apoptosis. The melanomas recur at the same location following reactivation of MITF activity (Supplementary Figure S3 online), although at this stage we cannot distinguish whether this reflects incomplete tumor regression or a cancer-initiating population that can survive with low-to-no MITF activity. Notably, although melanophages are presumably participating in melanoma regression and/or clearance (Figure 5), we do not know their function in melanoma growth (Figure 2a): macrophages can lead to both melanoma regression (Nakashima et al., 2012) and promotion (Zaidi et al., 2011), or form melanoma–macrophage hybrids (Pawelek, 2007).

In conclusion, our zebrafish model provides in vivo genetic evidence that targeting MITF activity—either directly or through regulators of MITF—may be an effective approach to melanoma therapy. Critically, our studies show that although targeting MITF activity is a potent antitumor mechanism, it must be done with caution because partial or ineffective targeting of MITF is oncogenic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All zebrafish work was done in accordance with the United Kingdom Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986) and approved by the University of Edinburgh Ethical Review Committee, and in the United States in compliance with protocol AM10415, approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University. The temperature-sensitive mitfavc7 mutant is described in Johnson et al. (2011), and the mitfavc7 phenotypes were first inadvertantly ascribed to the mitfafh53mutant.

Histopathology

Adult zebrafish were prepared for histopathology as described previously (Patton et al., 2011). Antibodies and antigen retrieval methods were as follows: anti-phospho-extracellular signal–regulated kinase 1/2, 1:1,000, EDTA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); p53 5.1, 1:500, citrate buffer; phospho-histone H3, 1:1,000, citrate buffer (Cell Signaling Technology); Melan-A, 1:75, citrate buffer (DAKO, Cambridge, UK). For the proliferation analysis, the total melanoma cell population in each of the six images was counted (between 1,000 and 3,000 cells) and the percentage of phospho-histone H3–stained cells calculated.

PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). First-strand complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA in a 10 μl reaction using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Complementary DNA was then amplified by PCR using primers covering the alternative splicing region in the mitfavc7 gene. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green Jumpstart Taq Readymix for high-throughput real-time PCR (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Reactions were run in an ABI PRISM 7900 HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Paisley, UK) using the SYBR Green protocol. The zebrafish β-actin gene was used as reference. Primers sequences are presented in Supplementary Table S1 online.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nick Hastie, Margaret Frame, James Amatruda, and Kerrie Marie for the critical reading of the manuscript; Katie Lunney and Leyla Peachy for zebrafish husbandry; and David Lane for the zebrafish p53 antibody. This work was funded by a Concern Foundation for Cancer Research CONCERN (CONquer canCER Now) Award (to JAL), a FP7-Framework ZF-Cancer grant (to EEP), the Wellcome Trust (to EEP), Medical Research Scotland (to JR and EEP), and the Medical Research Council (to AC, JR, ZZ, KP, IJJ, and EEP).

Glossary

- MITF

microphthalmia-associated transcription factor

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/jid

Supplementary Material

References

- Bertolotto C, Lesueur F, Giuliano S, et al. A SUMOylation-defective MITF germline mutation predisposes to melanoma and renal carcinoma. Nature. 2011;480:94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature10539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuret L, Flori E, Denoyelle C, et al. Up-regulation of MET expression by alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone and MITF allows hepatocyte growth factor to protect melanocytes and melanoma cells from apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14140–14147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611563200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceol CJ, Houvras Y, Jane-Valbuena J, et al. The histone methyltransferase SETDB1 is recurrently amplified in melanoma and accelerates its onset. Nature. 2011;471:513–517. doi: 10.1038/nature09806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheli Y, Giuliano S, Fenouille N, et al. Hypoxia and MITF control metastatic behaviour in mouse and human melanoma cells. Oncogene. 2012;10:2461–2470. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheli Y, Giuliano S, Botton T, et al. Mitf is the key molecular switch between mouse or human melanoma initiating cells and their differentiated progeny. Oncogene. 2011;30:2307–2318. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheli Y, Ohanna M, Ballotti R, et al. Fifteen-year quest for microphthalmia-associated transcription factor target genes. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:27–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin JC, Wunderlich J, Loftus SK, et al. Frequent mutations in the MITF pathway in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22:435–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley CM, Mongera A, Walderich B, et al. On the embryonic origin of adult melanophores: the role of ErbB and Kit signalling in establishing melanophore stem cells in zebrafish. Development. 2013;140:1003–1013. doi: 10.1242/dev.087007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Miller AJ, Widlund HR, et al. MLANA/MART1 and SILV/PMEL17/GP100 are transcriptionally regulated by MITF in melanocytes and melanoma. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:333–343. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63657-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty KT, Hodi FS, Fisher DE. From genes to drugs: targeted strategies for melanoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nrc3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraway LA, Widlund HR, Rubin MA, et al. Integrative genomic analyses identify MITF as a lineage survival oncogene amplified in malignant melanoma. Nature. 2005;436:117–122. doi: 10.1038/nature03664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano S, Cheli Y, Ohanna M, et al. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor controls the DNA damage response and a lineage-specific senescence program in melanomas. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3813–3822. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall J, Carreira S, Denat L, et al. Brn-2 represses microphthalmia-associated transcription factor expression and marks a distinct subpopulation of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor-negative melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7788–7794. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray-Schopfer V, Wellbrock C, Marais R. Melanoma biology and new targeted therapy. Nature. 2007;445:851–857. doi: 10.1038/nature05661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handerson T, Berger A, Harigopol M, et al. Melanophages reside in hypermelanotic, aberrantly glycosylated tumor areas and predict improved outcome in primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:679–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek KS, Goding CR. Cancer stem cells versus phenotype-switching in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:746–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L, Pavan WJ. Transcriptional and signaling regulation in neural crest stem cell-derived melanocyte development: do all roads lead to Mitf. Cell Res. 2008;18:1163–1176. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Nguyen AN, Lister JA. mitfa is required at multiple stages of melanocyte differentiation but not to establish the melanocyte stem cell. Dev Biol. 2011;350:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SM, Dai J, Li S, et al. Human skin neural crest progenitor cells are susceptible to BRAF(V600E)-induced transformation. Oncogene. 2013. pp. 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Levy C, Khaled M, Fisher DE. MITF: master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister JA, Robertson CP, Lepage T, et al. nacre encodes a zebrafish microphthalmia-related protein that regulates neural-crest-derived pigment cell fate. Development. 1999;126:3757–3767. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas JB, Littlejohn EL, Wolsky RJ, et al. PAX3 and SOX10 activate MET receptor expression in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:225–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill GG, Haq R, Nishimura EK, et al. c-Met expression is regulated by Mitf in the melanocyte lineage. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10365–10373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima H, Miyake K, Clark CR, et al. Potent antitumor effects of combination therapy with IFNs and monocytes in mouse models of established human ovarian and melanoma tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:1081–1092. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1152-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton EE, Mathers ME, Schartl M. Generating and analyzing fish models of melanoma. Methods Cell Biol. 2011;105:339–366. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381320-6.00014-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton EE, Widlund HR, Kutok JL, et al. BRAF mutations are sufficient to promote nevi formation and cooperate with p53 in the genesis of melanoma. Curr Biol. 2005;15:249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelek JM. Viewing malignant melanoma cells as macrophage-tumor hybrids. Cell Adh Migr. 2007;1:2–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salti GI, Manougian T, Farolan M, et al. Micropthalmia transcription factor: a new prognostic marker in intermediate-thickness cutaneous malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5012–5016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer E, Wacheck V, Lucas T, et al. The melanocyte-specific isoform of the microphthalmia transcription factor affects the phenotype of human melanoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2098–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strub T, Giuliano S, Ye T, et al. Essential role of microphthalmia transcription factor for DNA replication, mitosis and genomic stability in melanoma. Oncogene. 2011;30:2319–2332. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KL, Lister JA, Zeng Z, et al. Differentiated melanocyte cell division occurs in vivo and is promoted by mutations in Mitf. Development. 2011;138:3579–3589. doi: 10.1242/dev.064014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao H, Chin L, Garraway LA, et al. Melanoma: from mutations to medicine. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1131–1155. doi: 10.1101/gad.191999.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viros A, Fridlyand J, Bauer J, et al. Improving melanoma classification by integrating genetic and morphologic features. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellbrock C, Marais R. Elevated expression of MITF counteracts B-RAF-stimulated melanocyte and melanoma cell proliferation. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:703–708. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellbrock C, Rana S, Paterson H, et al. Oncogenic BRAF regulates melanoma proliferation through the lineage specific factor MITF. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman DC, Pavan WJ, Bastian BC. The melanomas: a synthesis of epidemiological, clinical, histopathological, genetic, and biological aspects, supporting distinct subtypes, causal pathways, and cells of origin. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:879–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama S, Woods SL, Boyle GM, et al. A novel recurrent mutation in MITF predisposes to familial and sporadic melanoma. Nature. 2011;480:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature10630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi MR, Davis S, Noonan FP, et al. Interferon-gamma links ultraviolet radiation to melanomagenesis in mice. Nature. 2011;469:548–553. doi: 10.1038/nature09666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.