Abstract

Objective To review the beneficial and harmful effects of laughter.

Design Narrative synthesis.

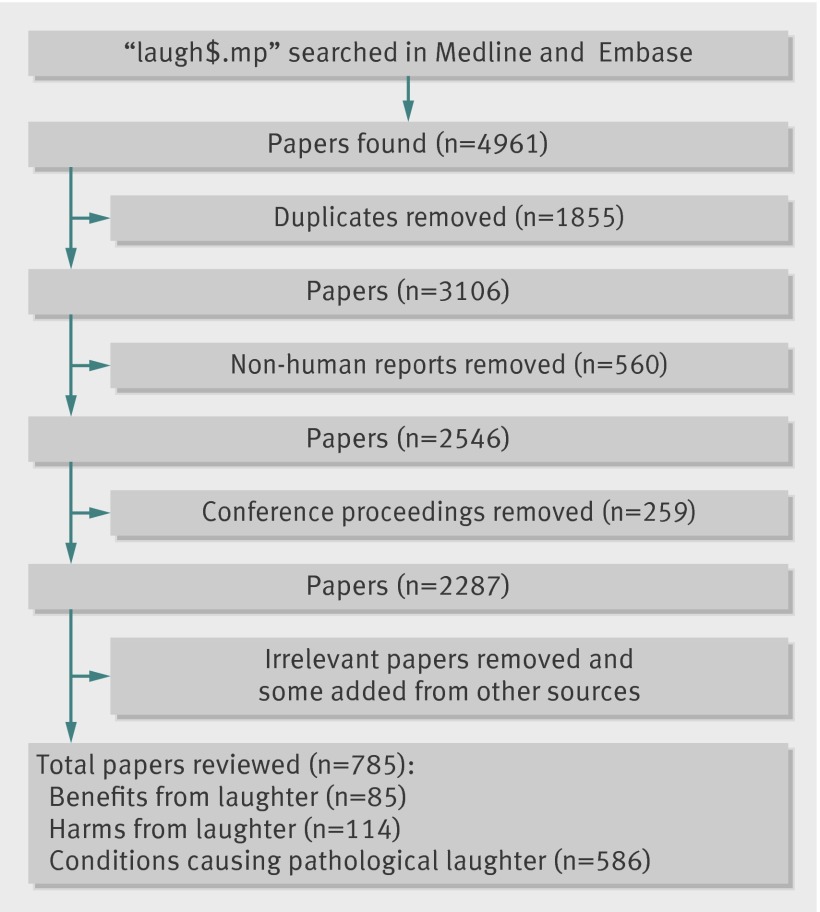

Data sources and review methods We searched Medline (1946 to June 2013) and Embase (1974 to June 2013) for reports of benefits or harms from laughter in humans, and counted the number of papers in each category.

Results Benefits of laughter include reduced anger, anxiety, depression, and stress; reduced tension (psychological and cardiovascular); increased pain threshold; reduced risk of myocardial infarction (presumably requiring hearty laughter); improved lung function; increased energy expenditure; and reduced blood glucose concentration. However, laughter is no joke—dangers include syncope, cardiac and oesophageal rupture, and protrusion of abdominal hernias (from side splitting laughter or laughing fit to burst), asthma attacks, interlobular emphysema, cataplexy, headaches, jaw dislocation, and stress incontinence (from laughing like a drain). Infectious laughter can disseminate real infection, which is potentially preventable by laughing up your sleeve. As a side effect of our search for side effects, we also list pathological causes of laughter, among them epilepsy (gelastic seizures), cerebral tumours, Angelman’s syndrome, strokes, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neuron disease.

Conclusions Laughter is not purely beneficial. The harms it can cause are immediate and dose related, the risks being highest for Homeric (uncontrollable) laughter. The benefit-harm balance is probably favourable. It remains to be seen whether sick jokes make you ill or jokes in bad taste cause dysgeusia, and whether our views on comedians stand up to further scrutiny.

Introduction

“Mirth . . . prorogues life, whets the wit, makes the body young, lively, and fit for any manner of employment.”

Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621)

The BMJ has not dealt seriously with laughter since 1899, when an editorialist, following an Italian correspondent’s suggestion that telling jokes could treat bronchitis, proposed the term “gelototherapy” (in Greek gelōs means laughter; in Italian gelato means ice cream).1 The journal had, a year before, described heart failure following prolonged laughter in a 13 year old girl.2

Methods

We searched Medline from 1946 to June 2013 and Embase from 1974 to June 2013, using the search term “laugh$.mp” (fig 1), removing animal studies and conference reports, and excluding papers on the Caribbean sponge Prosuberites laughlini and with authors called Laughing,3 Laughter,4 Laughton, or McLaughlin; none was particularly amusing. We discarded papers with opaque titles, such as “Gelotophobia and thinking styles in Sternberg’s theory”,5 and publications that proved irrelevant, such as “Another exciting use for the cantaloupe”6 (which described practising endoscopy on melons). We identified three classes of findings: benefits from laughter, harms from laughter, and conditions causing pathological laughter. We discussed the uncertain cases.

Fig 1 Search strategy for papers

Benefits

Dr Patch Adams advocated therapeutic clowning, declaring that “I have done vast numbers of clowning experiments . . . and have found friendliness and celebrating life to be the heavy artillery of the love strategy.”7 However, the benefits of laughter have often been assumed rather than demonstrated.

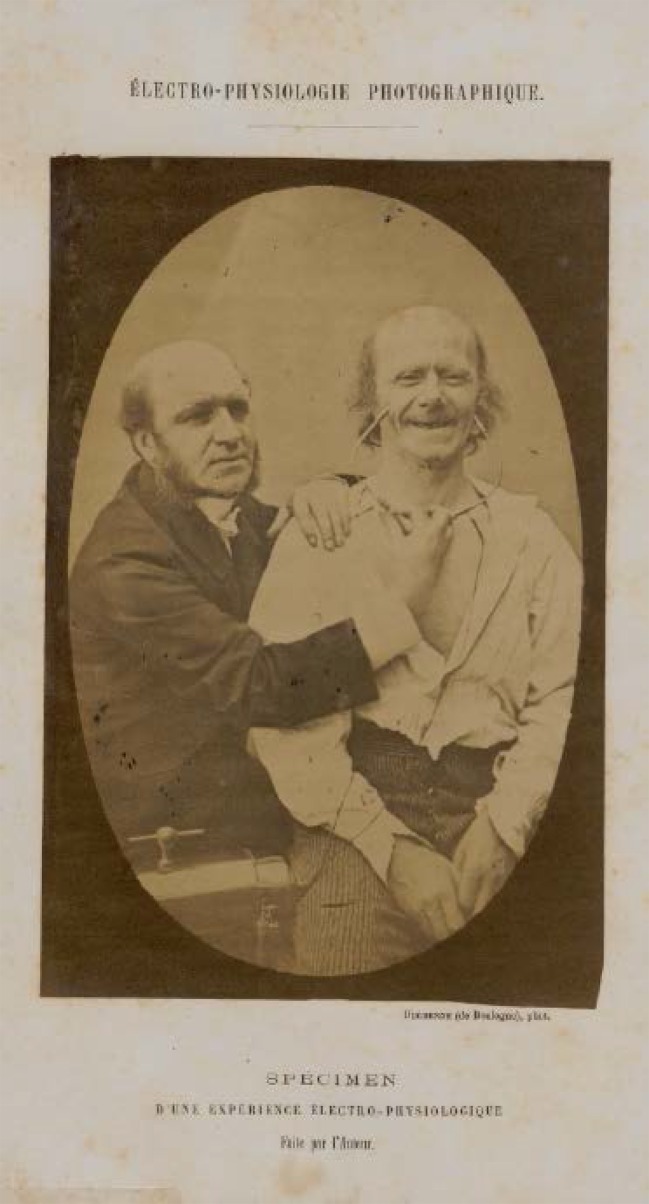

We concentrated on mirthful or “unintentional” laughter, also called Duchenne laughter, since Duchenne first demonstrated that genuine laughter is characterised by contraction of both the zygomatic and the orbicularis oculi muscles (fig 2).8

Fig 2 The frontispiece of Duchenne’s study of the electrophysiology of expression, showing the facial muscles activated in mirthful laughter

Psychological and psychiatric benefits

Life satisfaction and laughter have been associated with one another,9 but reciprocal causality has not been confirmed. Laughter can increase pain thresholds,10 although hospital clowns had no discernible effect on distress in children undergoing minor surgery.11 Perhaps surgical patients derive no advantage from being in stitches.

The presumed positive effects of laughter on wellbeing have been harnessed in serious mental disorders, without much evidence of benefit.12 13 14

Some psychoanalysts believe that a joke can substitute for interpretation—provided that the patient appreciates the joke. Others, however, view jokes as undesirable, because they circumvent resistance to psychic exposure and may be regarded as seductive.15 Ken Dodd pertinently observed that Freud, who thought that laughter conserved psychic energy, never played second house Friday night at the Glasgow Empire.

Cardiovascular benefits

Laughter reduces arterial wall stiffness16 and improves endothelial function.17 So perhaps it relieves more than one kind of tension. Laughing lowers your risk of myocardial infarction,18 and reduces recurrence after myocardial infarction in diabetes.19 So, reading the Christmas BMJ could add years to your life.

Respiratory benefits

Laughter induced by a clown improved lung function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.20 One of the study’s authors was a clown, something only alleged of other studies.

Metabolic benefits

In healthy people, “genuine laughter” for 15 minutes increased energy expenditure by up to 167.2 kJ (40 kcal).21 Laughter induced by a comedy show attenuated the postprandial increase in glucose in diabetes by 2.5 mmol/L compared with a “monotonous lecture.”22 A day of merriment could therefore consume over 8360 kJ (2000 kcal), improve glycaemic control, and cure obesity.

Obstetric benefits

Lord Chesterfield said of the act of procreation that “the pleasure is momentary, the position ridiculous, and the expense damnable.” His first proposition has been refuted,23 but a pioneering study has confirmed the second.24 A clown, dressed as a chef de cuisine, entertained would-be mothers for 12-15 minutes after in vitro fertilisation and embryo transfer. His saucy jokes were a recipe for success— the pregnancy rate was 36% in those whom he entertained compared with 20% in the controls (adjusted odds ratio 2.67; 95% confidence interval 1.36 to 5.24).25 Clowning may cost effectively vitiate Lord Chesterfield’s last proposition.

Otorhinolaryngological benefits

Sometimes life imitates art: “A surgeon proceeded to read [to me] the diverting history of ‘The Lady Rohesia’ [from The Ingoldsby Legends], and how she was cured of her quinsy . . . The story caused me to laugh, and this led to the bursting of the [tonsillar] abscess, and to my cure without the use of cold steel.”26

Immunological benefits

Laughter has no consistent effect on immune functions, such as the activity of natural killer cells.27 28 Work on how laughter affects IgE production by seminal cells in atopic eczema29 has sown the seeds for further studies.

Harms

Psychological harms

Humour weakens resolve and promotes brand preference,30 so the prudent response to the drug rep’s spiel would be “Don’t make me laugh.”

Cardiovascular harms

Hearty laughter can cause syncope,31 32 33 34 35 perhaps by a neural reflex response to the increase in intrathoracic pressure that accompanies intense laughter.36 37 Syncope after laughing has accompanied bilateral carotid stenosis in Takayasu arteritis.38 Laughing can cause conduction anomalies39 and arrhythmias.40 A woman with long QT syndrome and a history of torsade de pointes took ziprasidone, collapsed, and died after intense sustained laughter.41 Laughter in Angelman’s (“happy puppet”) syndrome can cause asystolic arrest, apparently of vagal origin.42 Laughing fit to burst can cause cardiac rupture.43

Respiratory harms

The quick intake of breath that accompanies laugher can provoke inhalation of foreign bodies.44

In patients with asthma, laughter sometimes triggers an attack,45 but cough after laughing is commoner than a good wheeze.46 47 Asthma was once perceived as a psychological disorder,48 but Gillespie noted that laughter probably had a physical rather than a psychological effect, and that even hollow (non-Duchenne) laughter could trigger an asthma attack.49

Laughter can cause pneumothorax.50 51 Pilgaard-Dahl syndrome, named after two Danish revue actors, is pneumothorax in middle aged smokers induced by laughter.52 If the YouTube video we have watched53 is representative, non-Danish speakers are not at risk.

Interlobular emphysema can reportedly result from “efforts of parturition and of defaecation, by the lifting of heavy weights, during coitus, by paroxysms of rage, excessive laughter, and hysterical convulsions.”54

Exhaled airflow—from sneezing, whistling, and laughing, for instance—potentially disseminates infection. Paper tissues may reduce spread.55 So, we suspect, might laughing up your sleeve.

Central nervous system harms

Cataplexy, often allied to narcolepsy (Gélineau’s syndrome),56 is characterised by sudden loss of muscle tone provoked by laughter and other stimuli.57 It is apparently difficult to elicit during medical consultations,58 perhaps because “laughing by itself” is a much less powerful stimulus than “laughing excitedly.”59 The combination of muscle weakness induced by laughter and the ability to hear during an episode distinguishes cataplexy from sleep apnoea.60 In one case, cataplexy induced by laughter affected only the right side of the body;61 this patient presumably could still laugh on the other side of her face.

Laughter, like many pleasurable things, including ice cream, chocolate, and sex (separately, and perhaps together), may precipitate headaches.62 The Chiari malformation and colloid cysts of the third ventricle are occasionally associated with laughter induced headache.63 64

A woman with a patent foramen ovale laughed uproariously for three minutes, became aphasic, and had a cerebral infarct.65

Gastrointestinal harms

A good belly laugh can make a hernia protrude, aiding diagnosis in children66—rapture unmasking rupture. By contrast, failure to laugh is an important sign of intra-abdominal infection in children.67 Laughter is an unusual precipitant of Boerhaave’s syndrome, spontaneous oesophageal perforation.68

Musculoskeletal harms

Laughing can dislocate the jaw.69 Rectus sheath haematoma is described as an adverse reaction to side splitting “laughter therapy.”70

Urinary tract harms

Laughing like a drain can cause stress incontinence.71 It can also cause “enuresis risoria” (“giggle micturition” or “giggle incontinence”),72 73 a consequence of uncontrolled detrusor contraction induced by laughing, for which methylphenidate has been advocated.74

Pathological causes of laughter

Laughter has its serious side. We have identified many disorders associated with unprovoked laughter, for example, gelastic seizures (seizures manifest by laughing—true nervous laughter; web table).

Limitations of the study

We limited our search to “laugh$,” and did not explicitly seek cacchinations, cackles, chortles, chuckles, giggles, grins, guffaws, smiles, smirks, sneers, sniggers, teehees, or titters; we also ignored sources of laughter (comedy, drollery, humour, jest, jocularity, whimsy, wit, and wisecracks).

Embase and Medline do not yet index some potential sources of information, including HUMOR: International Journal of Humor Research, Therapeutic Humor, Cahiers de recherche de CORHUM-CRIH, the European Journal of Humour Research, and the Israeli Journal of Humor Research (yet).75

We categorised effects as beneficial or harmful, a usually clear-cut distinction; some effects, however, such as lowering the threshold for seduction, could not be unequivocally categorised.

Some readers may ignore the benefits of laughter—that would be serious; others may dismiss its harms—we call them the laughing cavalier.

Discussion

Our review refutes the proposition that laughter can only be beneficial. However, invoking a pharmacological classification,76 the harms occur during prolonged overdose (toxic effects), occur immediately after exposure, and are most dangerous in those with susceptibility factors. We infer that laughter in any form carries a low risk of harm and may be beneficial.

These conclusions are necessarily tentative. It remains to be seen whether, for example, sick jokes make you ill, if dry wit causes dehydration, or jokes in bad taste cause dysgeusia, and whether our views on comedians stand up to further scrutiny.

Contributors: REF proposed a systematic review of the benefits and harms of laughter and conducted the initial search and classification. JKA checked that work and collated the data in the web table. Both wrote and revised the manuscript. REF acts as guarantor.

Funding: None was required.

Competing interests: The authors’ interests are unrelated to mirthful laughter and are generally not conducive to it; their senses of humour sometimes conflict. Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: None was required.

Data sharing: Dataset of references available from the corresponding author at r.e.ferner@bham.ac.uk.

The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;347:f7274

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Web table: Pathological conditions that reportedly cause laughter

References

- 1.Anonymous. Laughter as a therapeutic agent. BMJ 1899;1:989-90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. Heart disease from laughter. BMJ 1898;2:829. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giles BG, Findlay CS, Haas G, LaFrance B, Laughing W, Pembleton S. Integrating conventional science and aboriginal perspectives on diabetes using fuzzy cognitive maps. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:562-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz A, Matsui H, Laughter AH. Tritiated digoxin binding to (Na++K+)-activated adenosine triphosphatase: possible allosteric site. Science 1968;160:323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen GH, Liu Y. Gelotophobia and thinking styles in Sternberg’s theory. Psychol Rep 2012;110:25-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Empkie TM. Another exciting use for the cantaloupe. Family Med 1987;19:430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams P. Humour and love: the origination of clown therapy. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:447-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duchenne de Boulogne G-B. Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine. Analyse électro-physiologique de l’expression des passions. Ve Jules Renouard, 1862.

- 9.Hasan H, Hasan TF. Laugh yourself into a healthier person: a cross cultural analysis of the effects of varying levels of laughter on health. Int J Med Sci 2009;6:200-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunbar RI, Baron R, Frangou A, Pearce E, van Leeuwen EJ, Stow J, et al. Social laughter is correlated with an elevated pain threshold. Proc Roy Soc London Series B Biol Sci 2012;279:1161-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meisel V, Chellew K, Ponsell E, Ferreira A, Bordas L, García-Banda G. El efecto de los <<payasos de hospital>> en el malestar psicologico y las conductas desadaptativas de ninos y ninas sometidos a cirugia menor. Psicothema 2009;21:604-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gelkopf M. The use of humor in serious mental illness: a review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011;2011:342837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walter M, Hänni B, Haug M, Amrhein I, Krebs-Roubicek E, Müller-Spahn F, et al. Humour therapy in patients with late-life depression or Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22:77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelkopf M, Gonen B, Kurs R, Melamed Y, Bleich A. The effect of humorous movies on inpatients with chronic schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 2006;194:880-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergmann MS. The psychoanalysis of humor and humor in psychoanalysis. In: Barron JW (ed). Humor and psyche. Psychoanalytic perspectives. Analytic Press, 1999:chapter 1.

- 16.Vlachopoulos C, Xaplanteris P, Alexopoulos N, Aznaouridis K, Vasiliadou C, Baou K, Stefanadi E, Stefanadis C. Divergent effects of laughter and mental stress on arterial stiffness and central hemodynamics. Psychosom Med 2009;71:446-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugawara J, Tarumi T, Tanaka H. Effect of mirthful laughter on vascular function. Am J Cardiol 2010;106:856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark A, Seidler A, Miller M. Inverse association between sense of humor and coronary heart disease. Int J Cardiol 2001;80:87-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan SA, Tan LG, Lukman ST, Berk LS. Humor, as an adjunct therapy in cardiac rehabilitation, attenuates catecholamines and myocardial infarction recurrence. Adv Mind Body Med 2007;22:8-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brutsche MH, Grossman P, Müller RE, Wiegand J, Pello, Baty F, et al. Impact of laughter on air trapping in severe chronic obstructive lung disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2008;3:185-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchowski MS, Majchrzak KM, Blomquist K, Chen KY, Byrne DW, Bachorowski JA. Energy expenditure of genuine laughter. Int J Obes 2007;31:131-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi K, Hayashi T, Iwanaga S, Kawai K, Ishii H, Shoji S, et al. Laughter lowered the increase in postprandial blood glucose. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1651-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kratochvíl S. Trvani zenskeho orgasmu. [The duration of female orgasm.] Cesk Psychiatr 1993;89:296-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schultz WW, van Andel P, Sabelis I, Mooyaart E. Magnetic resonance imaging of male and female genitals during coitus and female sexual arousal. BMJ 1999;319:1596-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedler S, Glasser S, Azani L, Freedman LS, Raziel A, Strassburger D, et al. The effect of medical clowning on pregnancy rates after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Fertil Steril 2011;95:2127-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall F de H. Cure by laughter. BMJ 1913;967.

- 27.Hayashi T, Murakami K. The effects of laughter on post-prandial glucose levels and gene expression in type 2 diabetic patients. Life Sci 2009;85:185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett MP, Lengacher C. Humor and laughter may influence health. IV. Humor and immune function. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2009;6:159-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimata H. Viewing a humorous film decreases IgE production by seminal B cells from patients with atopic eczema. J Psychosom Res 2009;66:173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strick M, Holland RW, van Baaren RB, van Knippenberg A. Those who laugh are defenseless: how humor breaks resistance to influence. J Exp Psychol Appl 2012;18:213-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bloomfield D, Jazrawi S. Shear hilarity leading to laugh syncope in a healthy man. JAMA 2005;293:2863-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bragg MJ. Fall about laughing: a case of laughter syncope. Emerg Med Australas 2006;18:518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El Otmani H, Moutaouakil F, Fadel H, Slassi I. Syncopes gélastiques récurrentes. [Recurrent gelastic syncopes.] Rev Med Interne 2012;33:522-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amaki M, Kamide K, Takiuchi S, Niizuma S, Horio T, Kawano Y. A case of neurally mediated syncope induced by laughter successfully treated with combination of propranolol and midodrine. Int Heart J 2007;48:123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lo R, Cohen TJ. Laughter-induced syncope: no laughing matter. Am J Med 2007;120:e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishida K, Hirota SK, Tokeshi J. Laugh syncope as a rare sub-type of the situational syncopes: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2008;2:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarzi Braga S, Manni R, Pedretti RF. Laughter-induced syncope. Lancet 2005;366:426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah AA, Gelber AC. Laughter-induced syncope. Am J Med 2010;123:609-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chow GV, Desai D, Spragg DD, Zakaria S. Laughter-induced left bundle branch block. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2012;23:1136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cabot RC. Case 14111. Three months’ palpitation at twenty. N Engl J Med 1928;198:585-9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kadari R, Sarche MA, Krantz MJ. Fatal laughter. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vanagt WY, Pulles-Heintzberger CF, Vernooy K, Cornelussen RN, Delhaas T. Asystole during outbursts of laughing in a child with Angelman syndrome. Pediatr Cardiol 2005;26:866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Locke EA. Five cases of spontaneous rupture of the heart. Trans Am Climatol Clin Assoc 1927;43:30-46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fletcher GW. A review of thirty-three cases of foreign bodies in the oesophagus, bronchi and larynx. CMAJ 1921;11:332-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gayrard P. Should asthmatic patients laugh? Lancet 1978;2:1105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liangas G, Morton JR, Henry RL. Mirth-triggered asthma: is laughter really the best medicine? Pediatr Pulmonol 2003;36:107-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGarvey L, McKeagney P, Polley L, MacMahon J, Costello RW. Are there clinical features of a sensitized cough reflex? Pulmon Pharmacol Ther 2009;22:59-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams CT. The pathology and treatment of spasmodic asthma. BMJ 1874;1:769-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gillespie RD. Psychological factors in asthma. BMJ 1936;1:1285-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muller GP, Mogavero F. Spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Surg 1933;98:1018-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vrooman CH. Idiopathic spontaneous pneumothorax in apparently healthy adults. CMAJ 1934;30:265-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andreasen DB, El Fassi D. Pilgaard-Dahl-syndromet—latterinduceret pneumothorax. [The Pilgaard-Dahl syndrome: laughter-induced pneumothorax.] Ugeskr Laeger 2010;172:3496-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.YouTube. Godnat og farvel—Lisbeth Dahl og Ulf Pilgaard. 2010. www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&feature=endscreen&v=D8D_UDohmcc.

- 54.Skerritt EM. Clinical lecture on interlobular emphysema of the lungs: delivered at the Bristol General Hospital. BMJ 1892;1:1010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tang JW, Nicolle AD, Pantelic J, Jiang M, Sekhr C, Cheong DK, et al. Qualitative real-time schlieren and shadowgraph imaging of human exhaled airflows: an aid to aerosol infection control. PLoS One 2011;6:e21392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parkes JD, Chen SY, Clift SJ, Dahlitz MJ, Dunn G. The clinical diagnosis of the narcoleptic syndrome. J Sleep Res 1998;7:41-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anic-Labat S, Guilleminault C, Kraemer HC, Meehan J, Arrigoni J, Mignot E. Validation of a cataplexy questionnaire in 983 sleep-disorders patients. Sleep 999;22:77-87. [PubMed]

- 58.Lammers GJ, Overeem S, Tijssen MA, van Dijk JG. Effects of startle and laughter in cataplectic subjects: a neurophysiological study between attacks. Clin Neurophysiol 2000;111:1276-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Overeem S, van Nues SJ, van der Zande WL, Donjacour CE, van Mierlo P, Lammers GJ. The clinical features of cataplexy: a questionnaire study in narcolepsy patients with and without hypocretin-1 deficiency. Sleep Med 2011;12:12-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krahn LE, Lymp JF, Moore WR, Slocumb N, Silber MH. Characterizing the emotions that trigger cataplexy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005;17:45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lascelles RG, Mohr PD, Peart I. Unilateral cataplexy associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1976;39:1023-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levin M, Ward TN. Laughing headache: a novel type of triggered headache with response to divalproex sodium. Headache 2003;43:801-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morales-Asin F, Mauri JA, Iniguez C, Larrode MP, Mostacero E. Long-term evolution of a laughing headache associated with Chiari type 1 malformation. Headache 1998;38:552-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robbiolo L, Montanari G, Doneda P, Gatti A, Palmieri G. Episodi sincopali ricorrenti: una causa insolita. [Recurrent syncope: an unusual cause.] Internista 2005;13:52-6. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pandian JD, Perel R, Henderson RD, O’Sullivan JD, Read SJ. Unusual triggers for stroke. J Clin Neurosci 2007;14:786-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rourke JT. The laughing hernia sign. CMAJ 1988;138:721. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Van den Bruel A, Thompson M, Buntinx F, Mant D. Clinicians’ gut feeling about serious infections in children: observational study. BMJ 2012;345:e6144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Janjua KJ. Boerhaave’s syndrome. Postgrad Med J 1997;73:265-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chan TC, Harrigan RA, Ufberg J, Vilke GM. Mandibular reduction. J Emerg Med 2008;34:435-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sharma H, Shekhawat NS, Bhandari S, Memon B, Memon MA. Rectus sheath haematoma: a rare presentation of non-contact strenuous exercises. Br J Sports Med 2007;41:688-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Di Gangi Herms AM, Veit R, Reisenauer C, Herms A, Grodd W, Enck P, Stenzl A, Birbaumer N. Functional imaging of stress urinary incontinence. Neuroimage 2006;29:267-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anonymous. Giggle incontinence. Lancet 1982;1:1000-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brocklebank JT, Meadow SR. Cure of giggle micturition. Arch Dis Child 1981;56:232-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sher PK. Successful treatment of giggle incontinence with methylphenidate. Pediatr Neurol 1994;10:81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nissan E, Sover A. Inaugural editorial. Isr J Humor Res 2012;1:1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aronson JK, Ferner RE. Joining the DoTS. New approach to classifying adverse drug reactions. BMJ 2003;327:1222-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web table: Pathological conditions that reportedly cause laughter