Abstract

Introduction

Central blood pressure (BP), an important measure of cardiovascular risk, has been shown to be effectively reduced by calcium channel blockade with amlodipine (AML) plus renin–angiotensin system blockade by the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, perindopril (PER). The aim of the SEVITENSION study was to compare the central effects of PER/AML against renin–angiotensin system blockade with the angiotensin II receptor blocker olmesartan (OLM) plus AML.

Methods

In this multicenter, parallel group, non-inferiority study, patients received AML 10 mg during a 2- to 4-week run-in before randomization to 24 weeks of double-blind treatment with the fixed-dose combination of OLM/AML 40/10 mg or PER/AML 8/10 mg. Hydrochlorothiazide was added at Weeks 4, 8, or 12 in patients with inadequate BP control. The primary efficacy variable was the absolute change in central systolic BP (CSBP) from baseline to the final examination, measured by radial artery applanation tonometry and analyzed by parametric analysis of covariance. Secondary variables included 24-h ambulatory and seated BP measurements as well as BP normalization.

Results

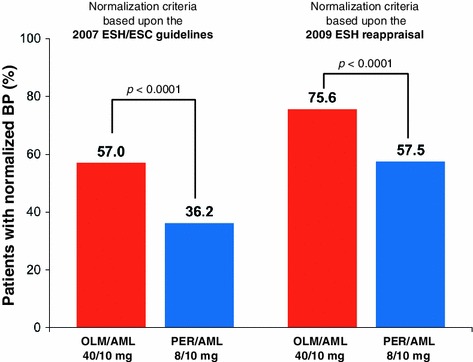

Of 600 patients enrolled, 486 were randomized (244 to OLM/AML 40/10 mg, 242 to PER/AML 8/10 mg). The reduction in CSBP was larger with OLM/AML (14.5 ± 0.83 mmHg) than with PER/AML (10.4 ± 0.84 mmHg). The between-group difference was −4.2 ± 1.18 mmHg with 95% confidence intervals (−6.48 to −1.83 mmHg) within the predefined non-inferiority margin (2 mmHg). An integrated superiority test confirmed that OLM/AML was superior to PER/AML (p < 0.0001) in reducing CSBP. The superiority of OLM/AML over PER/AML was also established for the majority of secondary efficacy variables; at the final examination, 75.6% of OLM/AML recipients achieved BP normalization (mean seated systolic BP/diastolic BP <140/90 mmHg) compared with 57.5% of PER/AML recipients (p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

The combination of OLM/AML was superior to PER/AML in reducing CSBP and other efficacy measures, including a significantly higher rate of BP normalization.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-013-0076-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, Angiotensin II receptor antagonist, Calcium channel blocker, Cardiology, Central systolic blood pressure, Fixed-dose combination, Non-invasive CV analysis system, Uncontrolled hypertension

Introduction

Studies over the last decade have shown that assessment of central blood pressure (CBP) provides important insights into the assessment of cardiovascular (CV) risk [1]. Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFE) was a sub-study [2] of the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA) study [3], which compared a combination of newer antihypertensive treatments with a combination of standard drugs. The ASCOT-BPLA study showed that calcium channel blockade with amlodipine (AML) combined with renin–angiotensin system (RAS) blockade using the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), perindopril (PER), produced significant benefits in terms of preventing major CV events and being associated with a lower incidence of new-onset diabetes compared with the β-blocker atenolol plus the diuretic bendroflumethiazide [3]. The CAFE sub-study was significant as it showed that patients treated with the calcium channel blocker (CCB) plus ACEI combination showed significantly larger reductions in central systolic blood pressure (CSBP) despite each group showing comparable levels of blood pressure (BP) measured by the conventional seated method. This indicated that the outcome benefits of the CCB plus ACEI combination seen in ASCOT-BPLA may have resulted from differences in CBP [2]. Observations such as these have led to increasing interest in CBP as a marker of CV risk, and its potential value is acknowledged by the 2013 European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology (ESH/ESC) hypertension guidelines [4].

Since the publication of the CAFE study, the ONgoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET) has shown that compared with ACEI treatment, RAS blockade with an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) provides equivalent CV protection combined with better tolerability [5]. However, information about the effects of an ARB plus CCB combination on CBP relative to an ACEI plus CCB combination is lacking.

Olmesartan medoxomil (OLM) is an ARB associated with strong antihypertensive efficacy, including 24-h BP reduction, and good tolerability [6–8]. Combination therapy with OLM and AML has been shown to provide increased BP-lowering capabilities compared with either agent as monotherapy [9, 10]. Furthermore, the fixed-dose combination containing these two agents (Sevikar®, Daiichi Sankyo Europe, GmbH, Munich, Germany), available on the European market since 2008, provides a suitable candidate for assessing the effects of ARB/CCB combination therapy on CBP.

The present efficacy of SEVIkar® compared to the combination of perindopril plus amlodipine on central arterial BP in patients with hyperTENSION (SEVITENSION) study was performed with the initial aim of demonstrating that treatment with an ARB plus AML has the same effect on CSBP as treatment with an ACEI plus AML. The SEVITENSION study compared the effects of 24 weeks of combination therapy with OLM/AML versus the combination of PER/AML on CSBP reduction in patients with hypertension plus three or more additional risk factors whose BP was inadequately controlled on AML 10 mg monotherapy. The dose of PER 8 mg with AML 10 mg was chosen to reflect the treatment used in the CAFE study, and the inclusion criteria were intended to select patients with similar characteristics to simplify the comparison of findings from the two studies.

Methods

The rationale and design of this randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority study (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01101009) have been described before [11]. Briefly, the study comprised a 2- to 4-week open-label run-in (which included a wash out from former antihypertensive treatment and ended with all patients receiving AML 10 mg) and a 24-week, double-blind treatment period. The study was carried out at 16 centers in Spain and recruited Caucasian men and women (aged ≥40 to ≤80 years) with hypertension, defined as systolic BP (SBP) ≥160 and ≤200 mmHg or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥100 and ≤115 mmHg in treatment-naive patients. To select patients with similar characteristics to those in the CAFE study, patients were also required to have ≥3 CV risk factors. Patients receiving antihypertensive treatment were included if their SBP was ≥140 mmHg or DBP ≥90 mmHg [SBP ≥130 mmHg or DBP ≥80 mmHg for patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease (CKD)]. The study and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, and the 2000 and 2008 revisions, and the International Conference on Harmonisation E6 Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, the European Commission Directive 2001/20 EC, the European Commission Directive 2005/28 EC and the European Commission Directive 95/46 EC. The study was approved by relevant Independent Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before being included in the study.

Interventions

During the first half of the run-in (Weeks −4 to −2), patients who had been receiving antihypertensive treatment prior to the study continued with their former medication (except for CCBs) and also received AML 5 mg once daily. During the last 2 weeks of the run-in, former antihypertensive medications were withdrawn and all patients were treated with AML 10 mg as their only antihypertensive medication. Patients who had been receiving AML 10 mg monotherapy prior to the study entered double-blind treatment directly. At Week 0, patients with inadequately controlled seated BP (SBP/DBP ≥140/90 mmHg, or ≥130/80 mmHg for patients with diabetes or CKD) were randomly allocated (1:1) to once daily treatment with either OLM/AML 40/10 mg fixed-dose combination, or a PER/AML 8/10 mg combination. At Week 4, inadequately controlled patients had open-label hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) 12.5 mg added to their treatment for the next 4 weeks. At Week 8, inadequately controlled patients received open-label HCTZ 12.5 mg, or if already receiving HCTZ, they had the dose uptitrated to 25 mg. Patients who reached target BP at Week 8 continued on the same dose of study medication. At Weeks 12 and 18, the protocol of maintaining patients at target BP on their existing treatment or adding/uptitrating HCTZ for patients not at target BP was applied. After Week 18, patients were maintained on their therapy until Week 24, unless their BP exceeded the specified limit (SBP ≥180 mmHg or DBP ≥110 mmHg).

Assessments

The primary efficacy variable was the absolute change in CSBP from baseline (Week 0) to the final examination (FE) (Week 24) with OLM/AML 40/10 mg versus PER/AML 8/10 mg using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach. Secondary variables included comparison of absolute changes from Week 0 to the FE for seated BP and for ambulatory SBP and DBP (mean 24-h, daytime and night-time) using the LOCF approach. The number and proportion of patients whose BP was normalized at the FE according to criteria based upon the 2007 ESH/ESC guidelines (SBP/DBP <140/90 mmHg, or <130/80 mmHg for diabetic/CKD patients) [12] and the 2009 ESH reappraisal (SBP/DBP <140/90 mmHg) were also compared [13]. Absolute changes from Week 0 to the FE in augmentation index and central diastolic BP (CDBP) with OLM/AML compared with PER/AML were also assessed (LOCF approach).

Safety parameters included adverse events (classified according to intensity as mild, moderate or severe), vital signs (heart rate and standing BP), and physical examinations. Laboratory tests were performed at study inclusion and additionally at the investigator’s discretion.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective was to show non-inferiority (one-sided, α = 0.025) of OLM/AML 40/10 mg compared with PER/AML 8/10 mg for the change in CSBP from Week 0 to the FE, which was analyzed by parametric analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with treatment as a main effect and baseline CSBP as a covariate using the LOCF approach. Due to the study design (non-inferiority), the main conclusions of the statistical analyses of the primary efficacy endpoint were based on the per protocol set (PPS), which included all members of the full analysis set (FAS) with no major protocol deviations. The FAS included all randomized patients who took at least one dose of double-blind medication and had CSBP measured at baseline and on at least one occasion during double-blind treatment. The FAS was used to analyze all efficacy variables, and was considered confirmatory for all except the primary efficacy variable due to the nature of the study (non-inferiority). The safety analysis set contained all enrolled patients who took at least one dose of AML during the run-in. The number and percentage of patients with normalized BP at Week 24 were analyzed with a χ 2 test using the LOCF approach.

Treatment with OLM/AML was to be considered non-inferior compared with PER/AML if the upper limit of the two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference in least-squares means for the change from baseline in CSBP between the two groups was less than 2 mmHg. If the upper limit of the 95% CI was less than 0 mmHg, then OLM/AML was to be considered superior to PER/AML. In a protocol amendment effected by a slowdown in recruitment, the power calculation was changed to 80% and the sample size of the PPS to 194 patients per treatment group.

Results

Patients

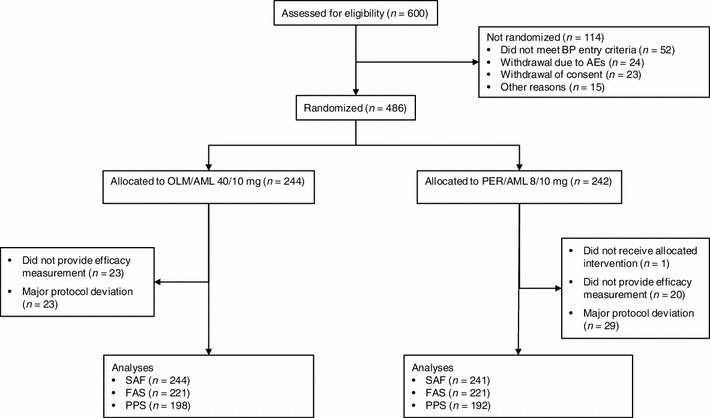

The first patient entered the study in April 2010 and the last patient follow-up was in November 2012. A total of 600 patients were enrolled in the study (Fig. 1) and 486 were randomized to double-blind treatment: 244 to OLM/AML and 242 to PER/AML. The FAS contained 442 patients (OLM/AML, n = 221; PER/AML, n = 221) and the PPS contained 390 patients (OLM/AML, n = 198; PER/AML, n = 192). The demographic and baseline characteristics of the 485 patients in the safety analysis set (one patient randomized to PER/AML was not treated and therefore excluded) are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in patient characteristics between the two treatment groups and demographic characteristics were also similar in the FAS and PPS groups. For the overall study population, mean age was 60.9 years, mean weight was 86.7 kg and mean body mass index was 31.3 kg/m2. The most common CV risk factors were dyslipidemia (91.1%), abdominal obesity (86.8%) and age (64.7%). The most frequent number of CV risk factors possessed by patients was four (37.3%), followed by three (29.7%) and five (22.3%).

Fig. 1.

Patient flow. AE adverse events, AML amlodipine, BP blood pressure, FAS full analysis set, OLM olmesartan, PER perindopril, PPS per protocol set, SAF safety analysis set

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients randomized to treatment (safety analysis set)

| Characteristic | OLM/AML 40/10 mg (n = 244) | PER/AML 8/10 mg (n = 241) | Total (n = 485) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 60.9 (9.21) | 60.8 (9.38) | 60.9 (9.28) |

| Male | 176 (72.1) | 180 (74.7) | 356 (73.4) |

| Caucasian | 244 (100.0) | 240 (99.6) | 484 (99.8) |

| Body weight, kg | 86.1 (15.12) | 87.2 (15.16) | 86.7 (15.14) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31.1 (4.14) | 31.5 (4.38) | 31.3 (4.26) |

| Males aged >55 years/females aged >65 years | 160 (65.6) | 154 (63.9) | 314 (64.7) |

| Smoker | 47 (19.3) | 76 (31.5) | 123 (25.4) |

| Dyslipidemia | 225 (92.2) | 217 (90.0) | 442 (91.1) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 111 (45.5) | 122 (50.6) | 233 (48.0) |

| Abnormal glucose tolerance test | 47 (19.3) | 52 (21.6) | 99 (20.4) |

| Abdominal obesity | 213 (87.3) | 208 (86.3) | 421 (86.8) |

| Family history of premature CV disease | 25 (10.2) | 26 (10.8) | 51 (10.5) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 24 (9.8) | 15 (6.2) | 39 (8.0) |

| Heart disease | 8 (3.3) | 12 (5.0) | 20 (4.1) |

| Advanced retinopathy | 2 (0.8) | 7 (2.9) | 9 (1.9) |

| Atherosclerosis | 10 (4.1) | 7 (2.9) | 17 (3.5) |

| Renal disease | 66 (27.0) | 67 (27.8) | 133 (27.4) |

Continuous variables are mean (SD), categorical variables are number of patients (%)

AML amlodipine, CV cardiovascular, OLM olmesartan, PER perindopril

Treatment Patterns

Overall, the mean duration of treatment was 152.6 days, and there were no major differences between the two treatment groups, including the duration of add-on HCTZ treatment. The mean (±standard deviation) dose of HCTZ was 10.6 (±9.61) mg in the OLM/AML group and 14.2 (±8.88) mg in the PER/AML group. Overall adherence was 99.3% in the OLM/AML group and 99.2% in the PER/AML group.

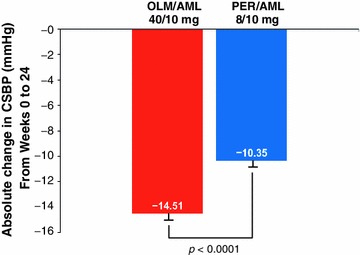

Primary Efficacy Variable

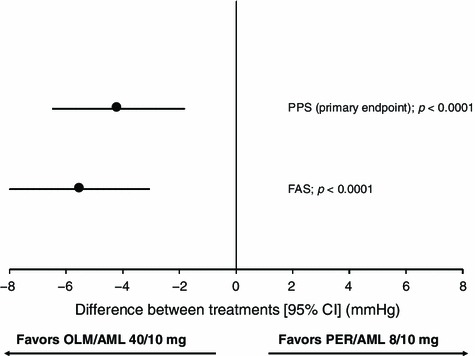

The absolute reduction in CSBP from baseline to the FE was statistically significantly larger in patients randomized to OLM/AML than PER/AML (Fig. 2). The point estimate for the between-group difference was −4.2 (SE 1.18) mmHg (95% CI −6.48 to −1.83 mmHg) in the PPS (Fig. 3). The upper limit of the CI was within the 2 mmHg non-inferiority margin and so OLM/AML 40/10 mg was established as non-inferior to PER/AML 8/10 mg (p < 0.0001). Furthermore, superiority of OLM/AML over PER/AML was indicated because the 95% CI for the treatment difference was below zero. The guidance of the Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products states that if the 95% CI for treatment effect lies above zero then there is evidence of statistical significance at the 5% level and it is acceptable to calculate the p value associated with a test of superiority [14]. The test integrated in the ANCOVA model confirmed the superiority of OLM/AML over PER/AML using the FAS as the primary test (p < 0.0001) and the PPS as a supportive test (p = 0.0005). Therefore, 24 weeks of treatment with OLM/AML was both non-inferior and superior to PER/AML with respect to the primary efficacy parameter of change in CSBP (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Absolute change from Week 0 to the final examination in mean central systolic blood pressure by treatment group (LOCF approach for the PPS). AML amlodipine, CSBP central systolic blood pressure, LOCF last observation carried forward, OLM olmesartan; PER perindopril, PPS per protocol set

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the differences between patients treated with OLM/AML 40/10 mg and PER/AML 8/10 mg in the absolute change from Week 0 to final examination in CSBP in the primary efficacy endpoint (PPS) and the FAS. P values represent the comparison between OLM/AML and PER/AML. Filled circles indicate the position of the point estimates for between-group differences and vertical lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals. AML amlodipine, BP blood pressure, CI confidence interval, FAS full analysis set, OLM olmesartan, PER perindopril, PPS per protocol set

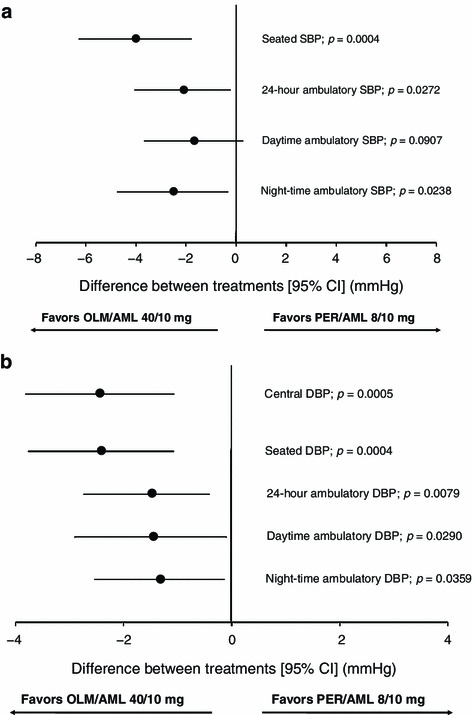

Secondary Efficacy Variables

As with the primary efficacy parameter, the superiority of OLM/AML over PER/AML was established for the majority of the secondary variables.

Hemodynamic variables

For each secondary variable, the FAS was used as a support for the main analysis and the PPS analysis. From Week 0 to the FE, the reduction in mean 24-h SBP and DBP was significantly larger in patients randomized to OLM/AML compared with PER/AML. For mean 24-h SBP, the 95% CI (Fig. 4a) was entirely below zero (FAS p = 0.0272), demonstrating superiority for OLM/AML compared with PER/AML. Similar results showing the superiority of OLM/AML compared with PER/AML were obtained for mean 24-h DBP (FAS p = 0.0079, Fig. 4b). The superiority of OLM/AML compared with PER/AML was also seen for night-time SBP (FAS p = 0.0238, Fig. 4a) and DBP (FAS p = 0.0359, Fig. 4b), as well as for daytime DBP (FAS p = 0.0290, Fig. 4b), with the reduction observed in the OLM/AML group being only numerically larger for daytime SBP.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the differences between patients treated with OLM/AML 40/10 mg and PER/AML 8/10 mg in the absolute change from Week 0 to the final examination in secondary a systolic BP parameters and b diastolic BP parameters. P values represent the superiority comparison between OLM/AML and PER/AML in the FAS. Filled circles indicate the position of the point estimates for between-group differences and vertical lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals. AML amlodipine, BP blood pressure, CI confidence interval, DBP diastolic blood pressure, FAS full analysis set, OLM olmesartan, PER perindopril, SBP systolic blood pressure

The mean reduction in seated SBP from Week 0 to FE with OLM/AML (−16.5 mmHg) was significantly larger compared to the PER/AML group (−12.5 mmHg, FAS p = 0.0004, Fig. 4a). Similarly, OLM/AML was also associated with a significantly larger decrease in seated DBP (−7.8 mmHg) than PER/AML (−5.4 mmHg, FAS p = 0.0004, Fig. 4b). The reduction in mean CDBP from Week 0 to FE was −2.4 mmHg (95% CI −3.81, −1.07) greater in patients treated with OLM/AML compared with PER/AML. The 95% CI for the treatment difference was below zero (Fig. 4b) demonstrating that the reduction in mean CDBP with OLM/AML was superior to PER/AML (FAS p = 0.0005). Generally, the statistically significant differences favoring OLM/AML seen using the FAS were confirmed by the p values seen for the same variables using the PPS.

Blood Pressure Normalization

At each time point during the study, the proportion of patients with normalized BP was higher in the group receiving OLM/AML than in the group receiving PER/AML. One definition of normalization was based upon the 2007 ESH/ESC guidelines (SBP/DBP <140/90 mmHg or <130/80 mmHg for diabetic/CKD patients) and the other one upon the 2009 ESH reappraisal (SBP/DBP <140/90 mmHg). At FE, treatment with OLM/AML was associated with a significantly higher proportion (p < 0.0001) of BP normalization, with 75.6% of patients achieving BP normalization (Fig. 5) compared with 57.5% with PER/AML using the 2009 ESH reappraisal criteria. The same significant difference (p < 0.0001) was seen for the 2007 ESH/ESC guideline criteria, in which treatment with OLM/AML was associated with BP normalization in 57.0% of patients compared with 36.2% of PER/AML patients.

Fig. 5.

Proportion of patients with blood pressure normalized at the final examination using criteria based upon the 2007 ESH/ESC guidelines (SBP/DBP <140/90 or <130/80 mmHg for diabetic/CKD patients) [12] and on the 2009 ESH reappraisal (SBP/DBP <140/90 mmHg) [13] in the FAS. AML amlodipine, CKD chronic kidney disease, DBP diastolic blood pressure, ESC European Society of Cardiology, ESH European Society of Hypertension, FAS full analysis set, OLM olmesartan, PER perindopril, SBP systolic blood pressure

Augmentation Index

In the OLM/AML group, a reduction in augmentation index was seen from baseline to FE of −1.3% (SE 0.65%). In contrast, a slight increase of 0.3% (SE 0.65%) was seen in the PER/AML group. The point estimate (95% CI) for the difference between OLM/AML and PER/AML was −1.67% (−3.48, 0.14).

Safety/Tolerability

Each treatment was well tolerated, and the proportion of patients with one or more drug-related treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was comparable for the OLM/AML (25.0%) and PER/AML (25.7%) groups. In the OLM/AML group, 5.7% of patients discontinued due to a drug-related TEAE and 7.5% did so in the PER/AML group (Table 2). The most common adverse event was peripheral edema, which was reported in 17.8% of OLM/AML patients and 18.1% of PER/AML recipients. Nasopharyngitis was reported in 4.5% of OLM/AML patients and 5.8% of PER/AML patients, and cough was reported in 2.0% of OLM/AML patients and 6.6% of PER/AML patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Safety observations during the double-blind treatment period

| Adverse event | OLM/AML 40/10 mg (n = 244) | PER/AML 8/10 mg (n = 241) | Total (n = 485) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥1 TEAE | 125 (51.2) | 114 (47.3) | 239 (49.3) |

| ≥1 drug-related TEAE | 61 (25.0) | 62 (25.7) | 123 (25.4) |

| ≥1 serious TEAE | 4 (1.6) | 4 (1.7) | 8 (1.6) |

| ≥1 serious drug-related TEAE | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ≥1 severe TEAE | 6 (2.5) | 5 (2.1) | 11 (2.3) |

| Deaths | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Discontinued due to TEAE | 18 (7.4) | 19 (7.9) | 37 (7.6) |

| Discontinued due to drug-related TEAE | 14 (5.7) | 18 (7.5) | 32 (6.6) |

| Patients with ≥1 TEAE | |||

| Peripheral edema | 43 (17.8) | 88 (18.1) | 45 (18.4) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 11 (4.5) | 14 (5.8) | 25 (5.2) |

| Cough | 5 (2.0) | 16 (6.6) | 21 (4.3) |

| Hypotension | 6 (2.5) | 2 (0.8) | 8 (1.6) |

| Bronchitis | 5 (2.0) | 2 (0.8) | 7 (1.4) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2.1) | 7 (1.4) |

| Erectile dysfunction | 3 (1.2) | 4 (1.7) | 7 (1.4) |

| Headache | 5 (2.0) | 2 (0.8) | 7 (1.4) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 3 (1.2) | 4 (1.7) | 7 (1.4) |

Data are number of patients (%)

AML amlodipine, OLM olmesartan, PER perindopril, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

Discussion

The SEVITENSION study in patients with hypertension plus additional CV risk factors and uncontrolled BP on AML monotherapy found that 24 weeks of treatment with the fixed-dose combination of OLM/AML was superior to the combination of PER/AML in reducing CSBP (the primary efficacy variable). The finding of superiority was observed for the analysis conducted in the PPS and the FAS, which further supports the superiority of OLM/AML over PER/AML. The superiority of OLM/AML was also demonstrated for CDBP, mean 24-h, night-time ambulatory BP, daytime ambulatory DBP, seated BP and BP normalization.

Growing evidence that CBP may predict CV damage and events more accurately than seated BP measurements has led to increased interest in studies using this index of CV risk [1, 4]. Following on from the CAFE study, the SEVITENSION study aimed to assess whether combined RAS and calcium channel blockade with an ARB/CCB combination lowers CSBP as effectively as an ACEI/CCB combination. The SEVITENSION results show that ARB/CCB treatment with OML/AML can reduce CSBP even more effectively than an ACEI/CCB (PER/AML) treatment. It is interesting to note that in contrast to the CAFE study, the greater reductions in CSBP seen here with OLM/AML were accompanied by similar positive effects on seated BP and 24-h ambulatory BP. It also appears from the difference in HCTZ exposure between the two groups that more patients in the PER/AML group were unable to achieve target BP with double-blind treatment and required HCTZ (12.5 or 25 mg) compared with the OLM/AML group (181 patients vs. 142 patients, respectively). The combination of OLM/AML compared with PER/AML also enabled significantly more patients to control their BP; 76% of OLM/AML recipients achieved BP normalization based upon the ESH 2009 criteria [13].

The basis for the significantly greater reduction in CSBP with OLM/AML may reflect the strong antihypertensive efficacy of OLM. In 2007, an independent evaluation of the effects of ARBs on seated and ambulatory BP showed that the drug used was a significant determinant of BP reductions [6]. It was evident from these data that OLM provided consistently strong BP-lowering properties over 24 h and during the last few hours of the dosing interval [6]. More recently, the widely used ACEI, ramipril, was directly compared with OLM in a population of elderly patients. The study showed that OLM-based treatment was associated with significantly larger BP reductions, including larger and more sustained reductions in BP over 24 h, a higher rate of BP goal achievement and more effective buffering of the early morning BP surge compared to ramipril [7, 15].

Some potential limitations of our study should be mentioned. Firstly, measurements of CSBP were indirect and based upon tonometry of radial artery pressure waveforms, which assumes close correspondence between calculated and actual values of CSBP. However, it should be noted that comparisons of directly measured and calculated aortic pressures using SphygmoCor devices carried out under controlled conditions have shown that the correspondence is within 1 mmHg [16, 17]. The design of our study was based upon the CAFE study, and the selection requirement for patients with ≥3 CV risk factors means that the findings are relevant to patients of this type, rather than the general hypertensive population. Another point is that patients in the study were all of Caucasian origin, which means that it may not be valid to extrapolate these findings to a non-Caucasian hypertensive population. It is possible that a different ACEI and CCB combination might provide more effective lowering of CSBP. However, information in this area is limited and the best data available come from the CAFE study, which means that PER/AML can be viewed as the ‘gold standard’. The doses of PER/AML, selection criteria and methods of assessment reflected those used in the CAFE study. However, the SEVITENSION study had a duration of double-blind treatment that was just under 6 months [mean (median) duration 152.6 (169.0) days] and involved fewer patients than the CAFE study. This means that assessment of treatment effects upon clinical events was beyond the scope of the study and the issue of whether the difference in CSBP seen here would translate into a significant difference in the rate of such clinical events must remain a matter of speculation.

The SEVITENSION study recruited high-risk patients characterized by the presence of three or more CV risk factors, including a substantial proportion with organ damage (including left ventricular hypertrophy, cerebrovascular disease, heart disease and renal disease). From this perspective, the present results have considerable relevance for such high-risk patients. Central measures of BP have been shown to correlate strongly with organ damage [18–20] and to be more strongly related to CV outcomes and mortality than conventional seated BP measurements [2, 21, 22]. The ability of OLM/AML to reduce CSBP significantly more than PER/AML thus raises the possibility of OLM/AML being associated with a greater beneficial effect in terms of reducing CV risk. Further evidence for this comes from the significantly higher rate of BP normalization achieved with OLM/AML compared with PER/AML. Reducing seated SBP/DBP to <140/90 mmHg has been shown in a number of studies to significantly reduce the risk of CV events [23–25].

Both OLM/AML and PER/AML therapy were well tolerated. A higher rate of cough and discontinuations due to cough was observed in patients treated with PER/AML, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

The SEVITENSION study demonstrated superior efficacy of OLM/AML in reducing central BP, as well as 24-h ambulatory BP and seated BP, compared with PER/AML in patients with hypertension and additional risk factors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo Europe GmbH, Munich, Germany. Prof. Dr. Luis Ruilope was the co-ordinating investigator and acted as the medical expert for the study. Dr. Angie Schaefer was the project leader of the study. Medical writing assistance during the preparation of this manuscript was funded by Daiichi Sankyo Europe GmbH and provided by Phil Jones, PhD, of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare, Chester, UK. Article processing charges for this study was funded by Daiichi Sankyo Europe GmbH. Professor Luis Ruilope is the guarantor for this article, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole. The authors wish to express their gratitude to the investigators, study nurses and co-ordinators who were involved in the SEVITENSION study. The SEVITENSION Study Investigators were: Jose Abellan, Pedro Aranda, Cesar Cerezo, Jose Antonio Divison, Luis Garcia Ortiz, Juan Garcia Puig, Pablo Gomez, Jorge Gomez Cerezo, Nieves Martell, Anna Oliveras, Enrique Rodilla, Jose Saban, Julian Segura, Carmen Suarez and Luis Vigil.

Conflict of interest

Prof. Dr. Ruilope has served as an advisor and speaker for Daiichi Sankyo. Dr. Angie Schaefer is an employee of Daiichi Sankyo Europe GmbH.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

The study and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, and the 2000 and 2008 revisions, and the International Conference on Harmonisation E6 Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, the European Commission Directive 2001/20 EC, the European Commission Directive 2005/28 EC and the European Commission Directive 95/46 EC. The study was approved by relevant Independent Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Footnotes

L. Ruilope: On behalf of the SEVITENSION Study Investigators.

Clinicaltrials.gov #NCT01101009.

References

- 1.Sharman JE, Laurent S. Central blood pressure in the management of hypertension: soon reaching the goal? J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27:405–411. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2013.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams B, Lacy PS, Thom SM, et al. Differential impact of blood pressure-lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes: principal results of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (CAFE) study. Circulation. 2006;113:1213–1225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.606962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlof B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:895–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–2219. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ONTARGET Investigators, Yusuf S, Teo KK, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547–59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Fabia MJ, Abdilla N, Oltra R, Fernandez C, Redon J. Antihypertensive activity of angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonists: a systematic review of studies with 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1327–1336. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280825625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malacco E, Omboni S, Volpe M, Auteri A, Zanchetti A. Antihypertensive efficacy and safety of olmesartan medoxomil and ramipril in elderly patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension: the ESPORT study. J Hypertens. 2010;28:2342–2350. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833e116b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott LJ, McCormack PL. Olmesartan medoxomil: a review of its use in the management of hypertension. Drugs. 2008;68:1239–1272. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868090-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volpe M, Brommer P, Haag U, Miele C. Efficacy and tolerability of olmesartan medoxomil combined with amlodipine in patients with moderate to severe hypertension after amlodipine monotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, multicentre study. Clin Drug Investig. 2009;29:11–25. doi: 10.2165/0044011-200929010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chrysant S, Melino M, Karki S, Lee J, Heyrman R. The combination of olmesartan medoxomil and amlodipine besylate in controlling high blood pressure: COACH, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week factorial efficacy and safety study. Clin Ther. 2008;30:587–604. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruilope LM, Schaefer A. Efficacy of Sevikar® compared to the combination of perindopril plus amlodipine on central arterial blood pressure in patients with moderate-to-severe hypertension: rationale and design of the SEVITENSION study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32:710–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) J Hypertens. 2007;25:1105–1187. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3281fc975a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mancia G, Laurent S, Agabiti-Rosei E, et al. Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension task force document. J Hypertens. 2009;27:2121–2158. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328333146d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP). Points to consider on switching between superiority and non-inferiority (CPMP/EWP/482/99). 2000: European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. http://www.emea.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500003658.pdf. Accessed Nov 14, 2013.

- 15.Omboni S, Malacco E, Mallion JM, Volpe M, Zanchetti A, Study G. Twenty-four hour and early morning blood pressure control of olmesartan vs. ramipril in elderly hypertensive patients: pooled individual data analysis of two randomized, double-blind, parallel-group studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1468–1477. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835466ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pauca AL, O’Rourke MF, Kon ND. Prospective evaluation of a method for estimating ascending aortic pressure from the radial artery pressure waveform. Hypertension. 2001;38:932–937. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.096106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Rourke MF, Pauca AL. Augmentation of the aortic and central arterial pressure waveform. Blood Press Monit. 2004;9:179–185. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang KL, Cheng HM, Chuang SY, et al. Central or peripheral systolic or pulse pressure: which best relates to target organs and future mortality? J Hypertens. 2009;27:461–467. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283220ea4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliveras A, Garcia-Ortiz L, Segura J, et al. Association between urinary albumin excretion and both central and peripheral blood pressure in subjects with insulin resistance. J Hypertens. 2013;31:103–108. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835ac7b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kizer JR, et al. Central pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure: the Strong Heart Study. Hypertension. 2007;50:197–203. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pini R, Cavallini MC, Palmieri V, et al. Central but not brachial blood pressure predicts cardiovascular events in an unselected geriatric population: the ICARe Dicomano Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2432–2439. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams B, Lacy PS. Central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1123–1125. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832b6566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Zhang Y, Liu G, et al. The Felodipine Event Reduction (FEVER) Study: a randomized long-term placebo-controlled trial in Chinese hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2005;23:2157–2172. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000194120.42722.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber MA, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Blood pressure dependent and independent effects of antihypertensive treatment on clinical events in the VALUE Trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2049–2051. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16456-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pepine CJ, Kowey PR, Kupfer S, et al. Predictors of adverse outcome among patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:547–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.