The incidence and mortality of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in France is relatively low despite the traditionally high intake of saturated fat.[1,2] The “French paradox” has been postulated to be related to the widespread consumption of wine.[2,3] However, this French paradox is being questioned and the results from the MONICA studies showed that France is not lowest among populations for CVD.[4,5] Thus, France would not be an exception, but would follow that geographic gradient. Although numerous epidemiologic studies have provided evidence for a French exception,[6] some studies have not found any difference between beer, wine and spirits in their relation to CVD or CVD risk factors.[7,8] Gronbaek et al. showed a strong association between light and moderate wine drinking and decreased mortality from CVD and other causes, whereas a similar intake of alcohol from spirits led to increased risk.[9] This difference has been attributed to prospective substances other than alcohol, e.g. antioxidants such as flavonoids, which are abundant in red wine.[10,11,12]

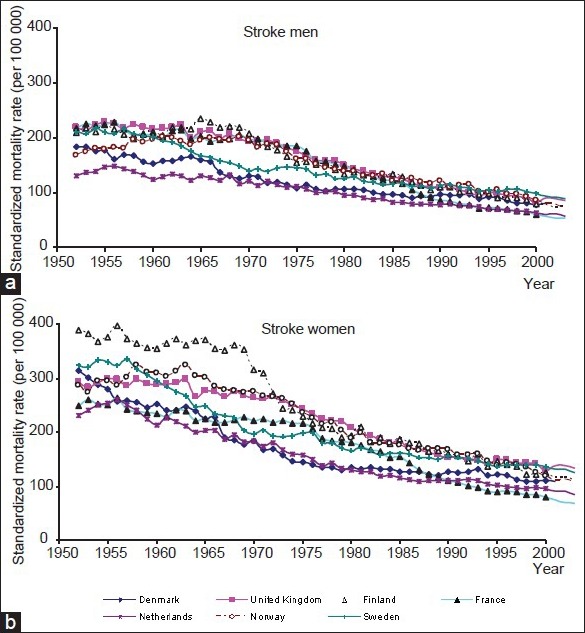

We performed a time series analysis in which special attention was paid to cohort patterns.[13] We studied mortality trends of ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke in birth cohorts born between 1860 and 1939 in seven low-mortality European countries; i.e. Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and England and Wales. The IHD mortality increased between the 1950s and 1970s in all countries for both men and women, except for France with relatively less peak and more stable mortality trend compared with other countries [Figure 1]. For stroke, the France mortality was similar to other countries first, but started to decline much faster than other countries [Figure 2]. This French advantage would be repeated in the future too.[14,15,16]

Figure 1.

Mortality trends from ischemic heart disease in period of 1950-1999, by sex and country

Figure 2.

Mortality trends from stroke in period of 1950-1999, by sex and country

It seems that our results support the French paradox; however, the question still remains: Is this difference due to French paradox or other factors?

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Renaud S, de Lorgeril M. Wine, alcohol, platelets, and the French paradox for coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1992;339:1523–6. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91277-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Criqui MH, Ringel BL. Does diet or alcohol explain the French paradox? Lancet. 1994;344:1719–23. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92883-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renaud S, Ruf JC. The French paradox: Vegetables or wine. Circulation. 1994;90:3118–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.6.3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krobot K, Hense HW, Cremer P, Eberle E, Keil U. Determinants of plasma fibrinogen: Relation to body weight, waist-to-hip ratio, smoking, alcohol, age, and sex. Results from the second MONICA Augsburg survey 1989-1990. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12:780–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.7.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodward M, Lowe GD, Rumley A, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Philippou H, Lane DA, et al. Epidemiology of coagulation factors, inhibitors and activation markers: The Third Glasgow MONICA Survey. II. Relationships to cardiovascular risk factors and prevalent cardiovascular disease. Br J Haematol. 1997;97:785–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.1232935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renaud S, Gueguen R. The French paradox and wine drinking. Novartis Found Symp. 1998;216:208–17. doi: 10.1002/9780470515549.ch13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, Rosner B, et al. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of coronary disease in men. Lancet. 1991;338:464–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90542-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan JM, Ross RK, Gao YT, Henderson BE, Yu MC. Follow up study of moderate alcohol intake and mortality among middle aged men in Shanghai, China. BMJ. 1997;314:18–23. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7073.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grønbaek M, Deis A, Sørensen TI, Becker U, Schnohr P, Jensen G. Mortality associated with moderate intakes of wine, beer, or spirits. BMJ. 1995;310:1165–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6988.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hertog MG, Feskens EJ, Hollman PC, Katan MB, Kromhout D. Dietary antioxidant flavonoids and risk of coronary heart disease: The Zutphen Elderly Study. Lancet. 1993;342:1007–11. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92876-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frankel EN, Kanner J, German JB, Parks E, Kinsella JE. Inhibition of oxidation of human low-density lipoprotein by phenolic substances in red wine. Lancet. 1993;341:454–7. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90206-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frankel EN, Waterhouse AL, Kinsella JE. Inhibition of human LDL oxidation by resveratrol. Lancet. 1993;341:1103–4. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amiri M, Kunst AE, Janssen F, Mackenbach JP. Cohort-specific trends in stroke mortality in seven European countries were related to infant mortality rates. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:1295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amiri M. Early life conditions and trends in mortality at later life: Is there any Relationship? Int J Prev Med. 2011;2:53–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amiri M, Janssen F, Kunst AE. The decline in ischaemic heart disease mortality in seven European countries: Exploration of future trends. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:676–81. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.109058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunst AE, Amiri M, Janssen F. The decline in stroke mortality: Exploration of future trends in 7 Western European countries. Stroke. 2011;42:2126–30. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.599712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]