Abstract

Background:

Considering the importance to determine the reasons for the higher occurrence of congenital hypothyroidism (CH) in Iran, in this study we report the prevalence of permanent CH (PCH) in Isfahan province 7 years after initiation of CH screening program in Isfahan.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, children with a primary diagnosis of CH studied. They clinically examined and their medical files were reviewed by a pediatric endocrinologist. Considering screening and follow-up lab data, radiologic findings and the decision of pediatric endocrinologists the final diagnosis of PCH was determined.

Results:

A total of 464,648 neonates screened in Isfahan province. The coverage percent of the CH screening and recall rate was 98.9% and 2.1%, respectively. A total of 1990 neonates were diagnosed with primary CH. PCH was diagnosed in 410 neonates. The prevalence of PCH and transient CH (TCH) was 1 in 1133 and 1 in 294 live births. The most common etiology of CH was thyroid dyshormonogenesis.

Conclusions:

Though the prevalence of PCH is high, but the higher prevalence of CH in Isfahan is commonly due to cases with TCH. Hence, the necessity of determining new strategies for earlier diagnosis of patients with TCH is recommended.

Keywords: Congenital hypothyroidism, permanent, transient

INTRODUCTION

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) is the most common pediatrics endocrine disorder with prevalence of 1:2,000-1:4,000 live births.[1,2,3] The rate has reported to be lower in whites and blacks and higher in Hispanics and Asian countries.[4]

CH considered as one of the preventable causes of mental retardation due to the role of thyroid hormone in neurocognitive development in infants. Considering this fact, neonatal screening for CH has been developed in many countries in order to early diagnosis and treatment of CH and consequently preventing its related neurodevelopmental complication. Since the introducing of CH screening program in 1970 significant advances have been occurred in the procedure for achieving more optimal outcome.[1,5,6]

CH screening in Iran first implemented in 1987, before the salt iodization program and thereafter in some provinces and finally in 2005 it integrated into the National Health System.[7,8,9] In Isfahan, this program was initiated in 2002 as a pilot study and then integrated in nationwide CH screening program.[10] The results of CH screening in Iran indicated that the prevalence of CH in Iran is higher than others studies world-wide.[11,12,13]

CH is classified in two forms. In permanent form of CH, the deficiency of thyroid hormone is persistent and affected patients need lifelong treatment with levothyroxine, whereas in transient form of the disease hormone deficiency is temporary and they need treatment for the first few months or years of life. The most common etiology of permanent CH (PCH) is thyroid dysgenesis, which accounts for 85% of the cases and thyroid dyshormonogenesis accounts for 15% of cases.[14]

Prevalence of PCH and transient CH (TCH) have reported in many studies world-wide but in Iran there is few published data in this field due to that the nationwide screening program has been implanted recently in Iran. Existing data reported a higher rate of PCH in Iran.[15,16,17]

On the other hand, evidences suggested that the world-wide incidence of CH has been increased recently due to reasons such as improved protocol of CH screening, increased detection of transient form of the disease and environmental factors.[18,19] In our previous report from Isfahan city, both the prevalence of transient and permanent (1/760) forms of CH was higher.[15]

Considering that the main recourses allocation for CH screening in a community is designed according to the rate of its permanent forms[20] and the importance to determine the reasons for the higher occurrence of CH in Iran, in this study we report the prevalence of PCH in Isfahan province 7 years after initiation of the program in Isfahan.

METHODS

In this cross-sectional study, children with a primary diagnosis of CH referred to Isfahan Endocrine and Metabolism Research Center and all health centers in Isfahan province for treatment and follow-up from March 2002 to September 2009 during CH screening in Isfahan were enrolled.

The Medical Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol.

All children were recalled. They clinically examined and their medical files were reviewed by a pediatric endocrinologist. Considering screening and follow-up lab data, radiologic findings and the decision of pediatric endocrinologists the final diagnosis of PCH was determined. In cases with missing data, the data completed. Those who had not radiologic information referred for radiologic study after withdrawal of treatment at 3 years of age. Demographic and screening and follow-up data of patients with PCH was recorded.

The patients with PCH were classified in two groups as follows;

PCH after 3 years of treatment; those older than 3 years and the diagnosis was confirmed according to the screening program guideline (thyroid stimulating hormone [TSH] >10 mIU/l and T4 < 6.5 mg/dl after 4 weeks withdrawal)

PCH before 3 years of age; Those younger than 3 years and the diagnosis of PCH was made according to the TSH (>10 mIU/l after 1 year age) level during screening treatment and follow-up period, radiologic findings and decision of pediatric endocrinologists. CH screening in Isfahan.

From May 2002 to April 2005, T4 and TSH serum concentrations of all 3-7 day old newborns were measured by radioimmunoassay and immunoradiometric assay, respectively, using Kavoshyar (Iran-Tehran) kits. Thyroid function tests were performed by Berthold-LB2111 unit gamma counter equipment using serum samples. In this period neonates with TSH >20 were recalled.

After implementation of nationwide CH screening program in Iran in April 2005, screening was performed using filter paper. Neonates with TSH >10 were recalled and those with abnormal T4 and TSH levels on their second measurements (TSH >10 mIU/l and T4 < 6.5 μg/dl) were diagnosed as CH patient and received treatment and regular follow-up.

Levothyroxin was prescribed for hypothyroid neonates at a dose of 10-15 μg/kg/day as soon as the diagnosis was confirmed. Neonates with CH were followed-up according to the CH screening guideline for appropriate treatment regarding the level of TSH, T4, height, weight and other supplementary tests. In accordance with screening program, in order to provide a similar treatment and follow-up protocol, 2-3 workshops annually was held in different cities of the province.

Permanent and transient cases of CH were determined at the age of 3 years by measuring TSH and T4 concentrations 4 weeks after withdrawal of L-T4 therapy. Patients with elevated TSH levels (TSH >10 mIU/l) and decreased T4 levels (T4 < 6.5 μg/dl) were considered as PCH sufferers. The etiology of CH was determined by thyroid scan and/or ultrasound before treatment in the neonatal period or at the age of 3 years after confirming the permanency of CH.[15]

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software and ANOVA, t-test.

RESULTS

During the period of this study 464648 neonates screened in Isfahan province. The coverage percent of the CH screening was 98.9%. The rate of recall was 2.1%. 1990 Neonates were diagnosed with primary CH. Re-evaluation of the recorded data and final diagnosis of PCH and TCH in cases with primary CH took 18 months. PCH was diagnosed in 410 neonates. The prevalence of PCH and TCH was 1 in 1133 and 1 in 294 live births.

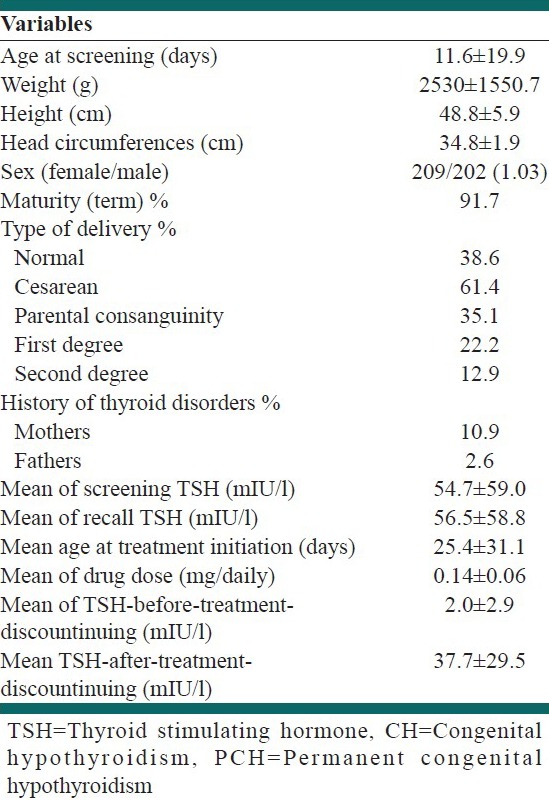

Characteristics of patients with PCH and their screening information are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and screening characteristics of patients with PCH

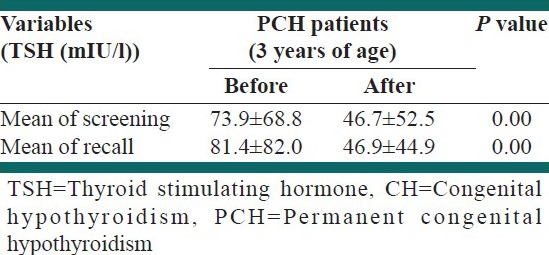

Screening information of patients with PCH diagnosed during follow-up (aged <3 years) and after 3 years of age is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Screening information of patients with PCH diagnosed during follow-up (aged <3 years) and after 3 years of age

According to sonographic findings 54.1% had thyroid dyshormonogenesis and 45.9% had thyroid dysgenesis (22.7% agenesis, 14.0% hemiagenesis, 4.8% hypoplasia of thyroid gland and 4.3% ectopia).

According to thyroid scintigraphy findings 58.3% had thyroid dyshormonogenesis and 41.7% had thyroid dysgenesis (26.7% agenesis, 1.6% hypoplasia of thyroid gland and 13.4% ectopia).

DISCUSSION

In this study, the prevalence of PCH among children with primarily diagnosed CH was investigated. The prevalence of PCH was high with a prevalence rate of 1 in 1133 live birth. The prevalence of TCH was 3-4 times higher than permanent form with a prevalence rate of 1 in 294 live births.

Though the prevalence of PCH in our study was higher comparing with other studies world-wide, but the results were in line with reports that the overall higher rate of CH in Isfahan-Iran is mainly due to the higher rate of TCH.[18]

Prevalence of PCH was reported to be 1 in 1662 in Babol-Iran, 1 in 2679 in Québec-Canada, 1 in 2418 in China and 1 in 1800 in Greece.[16,21,22,23]

In a study in Fars province, in the central part of Iran, Karamizadeh et al. have investigated the prevalence of overall and permanent and TCH. According to their results, the incidence of CH was 1:1465. The rate of permanent and TCH among primary diagnosed CH patients was 1 in 2740 and 1 in 3151 live birth, respectively.[17]

In a study in Babol, in the north of Iran, from screening of 10573 neonates the incidence of transient and permanent hypothyroidism in the studied infants was 5.7 and 20.8/10,000, respectively.[16]

In our previous study during 2002-2005, the prevalence of PCH and TCH was 1:748 and 1:1114 live births.[15]

The higher prevalence of CH in Isfahan was due to a higher rate of TCH whereas in other studies from Iran the rate of PCH is higher than TCH. It seems that it is due to the screening method (comparing with our previous study in Isfahan) or considering that the screening protocol is uniform, after nationwide screening program, in Iran, environmental or immunologic factors responsible for TCH should be studied. It is recommended to investigate the role of mentioned factors in TCH in our future studies. There are some studies in these fields in Isfahan but they implemented in a small sample size.[24,25]

In a study in USA, Eugster et al. have indicated that from 33 children with primary diagnosed CH 21 (64%) had PCH and 12 (36%) had TCH.[26] In the study of Karamizadeh et al., 53.6% and 46.4% of CH patients had PCH and TCH, respectively.[17]

In our study 20.6% of primarily diagnosed CH patients, diagnosed as PCH and a high proportion of them were patients with TCH.

In a study in Canada, Deladoëy et al. have evaluated the effect of different cut-off point of screening TSH on the incidence of CH. According to their result lowering the cut-off point have not significant effect on the incidence rate of a severe form of CH. It result in identifying more mild CH cases mostly functional disorders with a normal-size gland in situ and a normal or low isotope uptake.[21] Several studies have showed that these mild CH patients were permanent in 75-89% of cases.[21,27,28]

In this study, there were dissimilarities in some cases in sonographic and thyroid scan results; the final decision was made by a pediatric endocrinologist. These dissimilarities reported in many studies in this field,[29,30] but it is not the matter of this study and would be discussed in another study. The main outcome is that the most common etiology of PCH in our study was dyshormonogenesis and the most common cause of thyroid dysgenesis was thyroid agenesis, which was reported by other studies in Iran also.[15,17] The finding was in contrast with other studies in this field world-wide as the most common etiology of CH in 85% of cases is reported to be thyroid dysgenesis and thyroid ectopia is the most common cause of thyroid dysgenesis world-wide[15]

However, as reported by Karamizadeh et al. the etiology of CH in Iran is different from that reported by many studies world-wide.[17] The etiologic feature of our PCH patients is considered another challenging issue, which need more studies specially genetic ones.

In this study, the female to male ratio was 1.03 whereas several studies have indicated a 2/1 ratio.[31,32,33] The finding could be explained by different etiology of CH in our community and higher rate of consanguinity.

In the current study mean of both screening TSH level (filter paper) and recall TSH level (serum) was significantly higher in patients that the permanency of the disease was confirmed before 3 years of age, during follow-up than those diagnosed after 3 years of age. Obtained data could be used for determining the relation between these two groups of patients with the severity of CH, which should be investigated in our future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

It is suggested that though the prevalence of PCH is high but the higher prevalence of CH in Isfahan is commonly due to cases with TCH. Hence, the necessity of determining new strategies for earlier diagnosis of patients with TCH could not ignore in our screening program.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Rastogi MV, LaFranchi SH. Congenital hypothyroidism. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klett M. Epidemiology of congenital hypothyroidism. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1997;105(Suppl 4):19–23. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Najmi SB, Hashemipour M, Maracy MR, Hovsepian S, Ghasemi M. Intelligence quotient in children with congenital hypothyroidism: The effect of diagnostic and treatment variables. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18:395–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris KB, Pass KA. Increase in congenital hypothyroidism in New York State and in the United States. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;91:268–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dussault JH, Coulombe P, Laberge C, Letarte J, Guyda H, Khoury K. Preliminary report on a mass screening program for neonatal hypothyroidism. J Pediatr. 1975;86:670–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yordam N, Calikoğlu AS, Hatun S, Kandemir N, Oğuz H, Teziç T, et al. Screening for congenital hypothyroidism in Turkey. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:614–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02079061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ordookhani A, Mirmiran P, Hedayati M, Hajipour R, Azizi F. Screening for congenital hypothyroidism in Tehran and Damavand: An interim report on descriptive and etiologic findings, 1998. 2001. Iran J Endocrinol Metab. 2002;4:153–60. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karimzadeh Z, Amirhakimi GH. Incidence of congenital hypothyroidism in Fars province, Iran. Iran Med Sci. 1992;17:78–80. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hashemipour M, Amini M, Iranpour R, Sadri GH, Javaheri N, Haghighi S, et al. Prevalence of congenital hypothyroidism in Isfahan, Iran: Results of a survey on 20,000 neonates. Horm Res. 2004;62:79–83. doi: 10.1159/000079392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashemipour M, Dehkordi EH, Hovsepian S, Amini M, Hosseiny L. Outcome of congenitally hypothyroid screening program in Isfahan: Iran from prevention to treatment. Int J Prev Med. 2010;1:92–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Âkha O, Shabani M, Kowsarian M, Ghafari V, Saravi SN. Prevalence of congenital hypothyroidism in Mazandaran Province, Iran, 2008. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2011;21:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashemi Pour M, Taghavi A, Mosayyebi Z, Dana MK, Amini M, Iran Pour R, et al. Screening for congenital hypothyroidism in Kashan, Iran. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2005;14:91–83. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeinalzadeh AH, Talebi M. Neonatal screening for congenital hypothyroidism in East Azerbaijan, Iran: The first report. J Med Screen. 2012;19:123–6. doi: 10.1258/jms.2012.012024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Felice M, Di Lauro R. Thyroid development and its disorders: Genetics and molecular mechanisms. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:722–46. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashemipour M, Hovsepian S, Kelishadi R, Iranpour R, Hadian R, Haghighi S, et al. Permanent and transient congenital hypothyroidism in Isfahan-Iran. J Med Screen. 2009;16:11–6. doi: 10.1258/jms.2009.008090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haghshenas M, Zahed Pasha Y, Ahmadpour-Kacho M, Ghazanfari S. Prevalence of permanent and transient congenital hypothyroidism in Babol City -Iran. Med Glas (Zenica) 2012;9:341–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karamizadeh Z, Dalili S, Sanei-Far H, Karamifard H, Mohammadi H, Amirhakimi G. Does congenital hypothyroidism have different etiologies in Iran? Iran J Pediatr. 2011;21:188–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell ML, Hsu HW, Sahai I Massachusetts Pediatric Endocrine Work Group. The increased incidence of congenital hypothyroidism: Fact or fancy? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;75:806–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinton CF, Harris KB, Borgfeld L, Drummond-Borg M, Eaton R, Lorey F, et al. Trends in incidence rates of congenital hypothyroidism related to select demographic factors: Data from the United States, California, Massachusetts, New York, and Texas. Pediatrics. 2010;125(Suppl 2):S37–47. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1975D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parks JS, Lin M, Grosse SD, Hinton CF, Drummond-Borg M, Borgfeld L, et al. The impact of transient hypothyroidism on the increasing rate of congenital hypothyroidism in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;125(Suppl 2):S54–63. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1975F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deladoëy J, Ruel J, Giguère Y, Van Vliet G. Is the incidence of congenital hypothyroidism really increasing? A 20-year retrospective population-based study in Québec. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2422–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Q, Chen YL, Yu ZB, Han SP, Dong XY, Qiu YF, et al. Long-term consequences of the early treatment of children with congenital hypothyroidism detected by neonatal screening in Nanjing, China: A 12-year follow-up study. J Trop Pediatr. 2012;58:79–80. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmr010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skordis N, Toumba M, Savva SC, Erakleous E, Topouzi M, Vogazianos M, et al. High prevalence of congenital hypothyroidism in the Greek Cypriot population: Results of the neonatal screening program 1990-2000. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2005;18:453–61. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2005.18.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashemipour M, Abari SS, Mostofizadeh N, Haghjooy-Javanmard S, Esmail N, Hovsepian S, et al. The role of maternal thyroid stimulating hormone receptor blocking antibodies in the etiology of congenital hypothyroidism in Isfahan, Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:128–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashemipour M, Nasri P, Hovsepian S, Hadian R, Heidari K, Attar HM, et al. Urine and milk iodine concentrations in healthy and congenitally hypothyroid neonates and their mothers. Endokrynol Pol. 2010;61:371–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eugster EA, LeMay D, Zerin JM, Pescovitz OH. Definitive diagnosis in children with congenital hypothyroidism. J Pediatr. 2004;144:643–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbetta C, Weber G, Cortinovis F, Calebiro D, Passoni A, Vigone MC, et al. A 7-year experience with low blood TSH cutoff levels for neonatal screening reveals an unsuspected frequency of congenital hypothyroidism (CH) Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009;71:739–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leonardi D, Polizzotti N, Carta A, Gelsomino R, Sava L, Vigneri R, et al. Longitudinal study of thyroid function in children with mild hyperthyrotropinemia at neonatal screening for congenital hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2679–85. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang YW, Lee DH, Hong YH, Hong HS, Choi DL, Seo DY. Congenital hypothyroidism: Analysis of discordant US and scintigraphic findings. Radiology. 2011;258:872–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Bruyn R, Ng WK, Taylor J, Campbell F, Mitton SG, Dicks-Mireaux C, et al. Neonatal hypothyroidism: Comparison of radioisotope and ultrasound imaging in 54 cases. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990;79:1194–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1990.tb11409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connelly JF, Coakley JC, Gold H, Francis I, Mathur KS, Rickards AL, et al. Newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism, Victoria, Australia, 1977-1997. Part 1: The screening programme, demography, baseline perinatal data and diagnostic classification. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2001;14:1597–610. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2001.14.9.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sepandi M, Holakoei Naeini K, Yarahmadi SH, et al. Risk factors for congenital hypothyroidism in Fars Province, Iran, 2003-2006. J School Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2009;7:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghasemi M, Hashemipour M, Hovsepian S, Heiydari K, Sajadi A, Hadian R, et al. Prevalence of transient congenital hypothyroidism in central part of Iran. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18:699–703. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]