Abstract

Background:

The mother-generated index (MGI) is one of only a few existing specific questionnaires for assessing the postnatal quality of life (QoL). MGI is a single-form questionnaire that asks postnatal mothers to specify up to eight areas of their lives which have been affected by giving birth to a baby. Using this tool, it is possible to score and rank the QoL of mothers. This study aimed to validate the questionnaire for use in Iran.

Methods:

Forward translation was used to translate the questionnaire from English to Farsi (Persian). The questionnaire was then administered to a sample of postnatal women attending two teaching hospitals in Tehran, Iran. Face validity and criterion validity were performed to establish the validity for the Iranian version of the MGI. Face validity was assessed by asking women to indicate whether they understood the wording of the questions, how easy the questionnaire was, and so on. Criterion validity was examined using the Short Form 36-item (SF-36) Health Survey. It was hypothesized that the MGI would significantly correlate with the SF-36.

Results:

In all, 124 women were approached. Of these, 119 women were eligible and 96 women agreed to take part in the study. Face validity was good and all of the women found the MGI straightforward to complete; as criterion validity, the MGI scores and the subscales of the SF-36 were moderately correlated (for all subscales: Pearson r > 0.4; P < 0.001). The mean MGI primary score was 5.38 (SD = 3.05). Women who had comorbidity had significantly lower MGI scores than women without comorbidity (P = 0.04). Correlation between aggregate of comments and primary score was high (r = 0.68, P < 0.01).

Conclusions:

In general, the Iranian version of the MGI performed well and our data suggest that it is a valid measure to assess health-related QoL among postnatal women.

Keywords: Mother-Generated Index, postnatal, quality of life, validity

INTRODUCTION

It is now generally recognized that medical outcomes cannot be explained fully by an evaluation of clinical outcomes and clinical indicators alone. Factors such as pain, anxiety, and financial circumstances may influence health status, and also, subjective feelings of well-being affect the health of an individual.[1] Facts known only by physicians need to be complemented by values known only by patients. Outcomes of research have referred to the importance of the viewpoint of the patient on the objectives of medical care; measuring quality of life is one such ‘patient - centered’ outcome.[2]

Quality of life (QoL) is complex and comprehensive, and may be affected by many factors, including physical, psychological, emotional, social, sexual, and spiritual parameters.[3]

Over the last few decades, the importance of QoL has increased as an objective of medical care, and also methods of measurement of QoL have improved.[4] The concept of patient-reported QoL assessment is an emphasis on the fact that it is the patient, not the physician, who evaluates his or her QoL.[2] Hence, medical care aspires to narrow the gap between what the patient expects from the care she or he received, and what has been achieved in reality.[5]

Physical and psychological postnatal morbidity is an important health-care problem that requires better understanding.[6] There are validated tools for assessing postnatal QoL. As an example, the Maternal Postpartum Quality of Life (MAPP-QoL) tool measures QoL during the early postpartum period.[7,8] Like most QoL tools, MAPP-QoL involves asking a structured set of QoL questions to the target group. In addition, the mother-generated index (MGI) has been developed and validated for assessing postnatal QoL. The instrument allows postnatal women to select the QoL issues that are most important to them (hence ‘mother generated’), and thus avoids a top-down predefined approach to the assessment of QoL.[9]

The MGI allows the woman to determine both the content of the form and the overall score. This approach tries to assess QoL issues from the viewpoint of the woman herself.[10] In various studies, the MGI has correlated well with a range of other measures of postnatal index, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), the Maternal Adjustment and Maternal Attitudes Scale (MAMA), the Short Form-12, and general health questionnaire (GHQ-12), and was found to be acceptable and helpful.[3,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]

Although some studies have generally evaluated postpartum QoL in Iran,[18] no previous study has used a nongeneric specific QoL tool for postnatal issues in Iran. To date, no specific QoL instrument has been validated for use in the Farsi language for postnatal issues. The aim of this study was to examine whether the Iranian version of the MGI is a valid measure to assess the QoL of postnatal women. When comparing MGI and QoL scores, we hypothesized that a higher MGI score would be associated with less morbidity and higher QoL scores on generic QoL instruments.

METHODS

Translation

We first translated the MGI questionnaire from English to Farsi (Persian), that is, forward translation. As the questions of the MGI form were straightforward (it has only three questions and its content is largely determined by the responding mothers), it was felt that there was no need for back translating the MGI from Farsi to English. The same process was followed in Poland[19] and China (personal communication), and for the adaptation of other tools for use in Iran.[20]

The questionnaires

-

The MGI is a subjective postnatal QoL assessment tool developed from the patient-generated index[21]

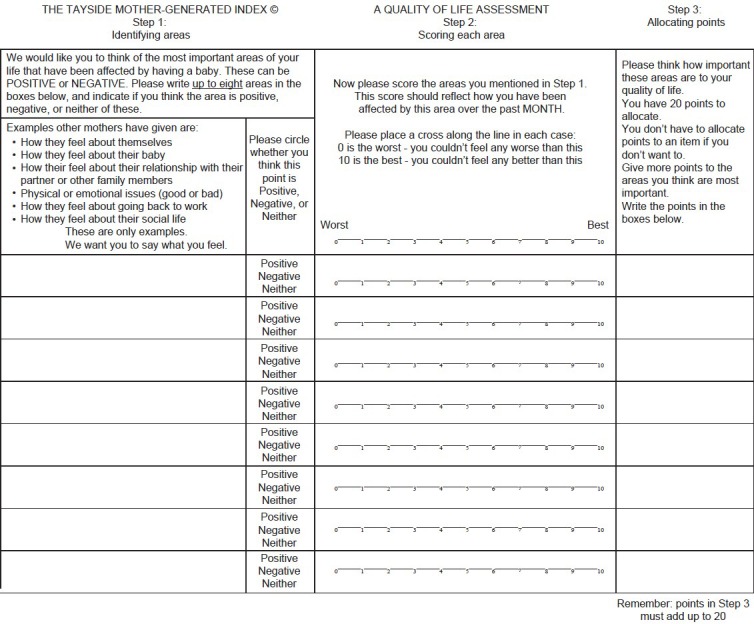

The MGI is a single-sheet three-step questionnaire (see additional File 1), that involves asking mothers to identify up to eight important QoL aspects, and scoring each aspect on three dimensions. The three steps are described below:

Step 1. Each postnatal woman identified those aspects of her life that were important to her having had a baby, also indicating whether these aspects were positive, negative, or both/neither. Respondents were allowed to identify a maximum of eight aspects

Step 2. The woman scored each aspect from zero (the worst she could possibly feel) to 10 (the best she could possibly feel) based on how she had been affected as a result of giving birth to a baby. The primary MGI score was the mean of the scores of the respondent to the identified aspects

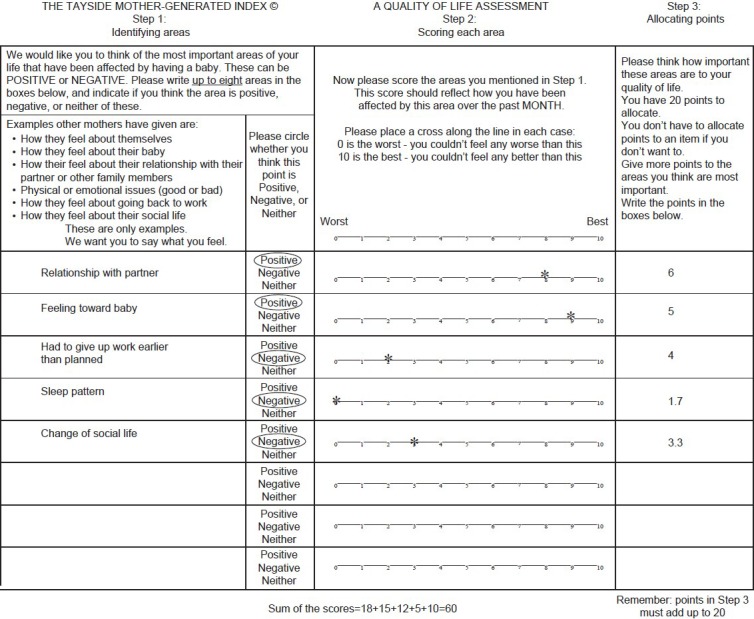

Step 3. In the original version of the MGI, the participants would ‘rank’ these aspects by allocating a total of 20 ‘spending points’ (weights) between them, with more points going to those areas that she felt were more important. The secondary ‘weighted’ MGI score was obtained from this step. Following the pilot study, minor modifications were made to the assignment of the weights and the calculation of secondary MGI score to make it easier for the participants to respond to the questionnaire. (We conducted these after discussions with AS, the developer of the MGI.) We asked the respondents to allocate a ‘point’ from 0-20 separately to each aspect. Then, we proportionately recalculated the weight of each aspect so that the total points (weights) obtained in Step 3 added up to 20. Hence for each aspect, the weight equaled ‘the point given by the respondent out of 20’ divided by ‘the sum of the points given by the respondent’ multiplied by 20. The secondary MGI score was the average of the scores obtained by multiplying the Step 2 score for each aspect with the weight score allocated to that aspect. An example demonstrating how the secondary MGI scores were calculated is shown in the additional File 2

We assessed patient-reported QoL using the Iranian version of the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).[22] It measured eight health-related concepts: Physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems, body pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitation due to emotional problems, and perceived mental health. The measures range from 0 to 100 with higher scores representing better QoL. The validity of the Iranian version of the SF-36 is well documented[23]

We collected data on age, educational attainment, smoking status, mode of delivery, and the number of children as a proxy of childbirth experiences. We also collected data on clinical history including hypertension, diabetes, renal dysfunction, liver dysfunction, cancer, arthritis, and whether they had experienced any postpartum medical complications.

The study sample

This cross-sectional study was conducted to recruit postpartum women who had delivered in the previous six weeks. Data collection was conducted by two researchers at the obstetrics and gynecology units of two teaching hospitals in Tehran affiliated to the Tehran University of Medical Sciences during January 2011 via face-to-face interviews. We conducted 96 interviews in total. Women were included in the study if: (1) They were at least 16 years of age; (2) their baby was alive; (3) they were able to read and understand the Farsi language; (4) they signed the written consent form.

Analysis

The aspects of the women's lives that had been affected since giving birth to the baby were coded as ‘Comments’ and categorized as themes by two researchers (RK, ZN) separately and there was a high degree of agreement between them. All disagreements were resolved via discussion. The individual respondent's aggregate scores of ‘Comments’ were obtained through subtracting the number of negative comments from the number of positive comments for that individual. Data were tested for skewness and were found to be normally distributed.

Descriptive statistics were used to estimate the distribution of maternal characteristics and health-related QoL scores in the study population. T-tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Pearson correlations were applied for analyzing the data.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Reference No: 130/1306). All participants signed the consent forms.

RESULTS

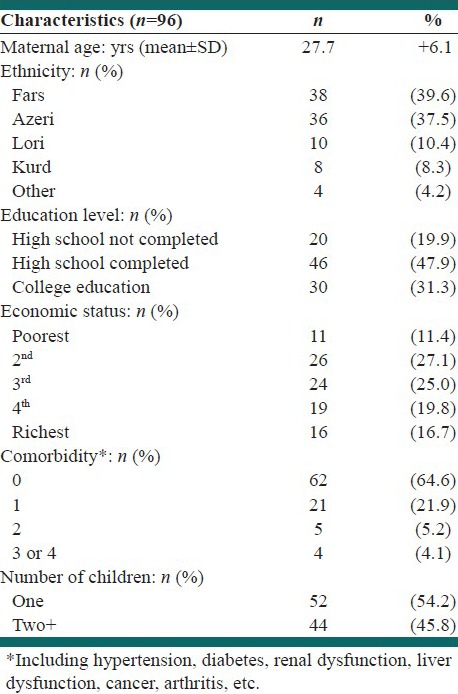

One hundred and twenty-four postnatal women were approached and five were excluded, two aged 15 years, two were severely ill, and one whose baby had died. Of the 119 remaining women, 96 (81%) mothers declared their consent to participate in the study. The main demographic variables among the study population are shown in Table 1. The average age of the participants was 27.7 years (SD: 6.1) and 54.2% were primiparous. None of the participants smoked cigarettes. Overall, 67.7% women had undergone a cesarean section, and 39.6 and 37.5% of the mothers had Fars and Azeri ethnic backgrounds, respectively. Also, the self-reported economic status of the household has been shown in Table 1. The participants commented on two to six (mean: 4.6; SD: 1.4) aspects of their life that had been affected since having a baby. Some comments were in single words and some were in short phrases. The mean of primary MGI scores (the scores given to the comments) was 5.38 [95% confidence interval (CI): 4.95-5.81].

Table 1.

Demographics of postnatal women

Of the comments made, 42% (152/364) were positive, 49% (182/364) were negative, and 9% (30/364) were both/neither. The mean of primary scores for positive comments was 8.37 (95% CI: 8.22-8.52); for negative comments it was 2.37 (95% CI: 2.20-2.54); for those that were labeled ‘both/neither’ it was 5.85 (95% CI: 5.62-6.08). The mean of the respondents’ comment aggregate scores was 0.11 (95% CI: −0.30-0.52).

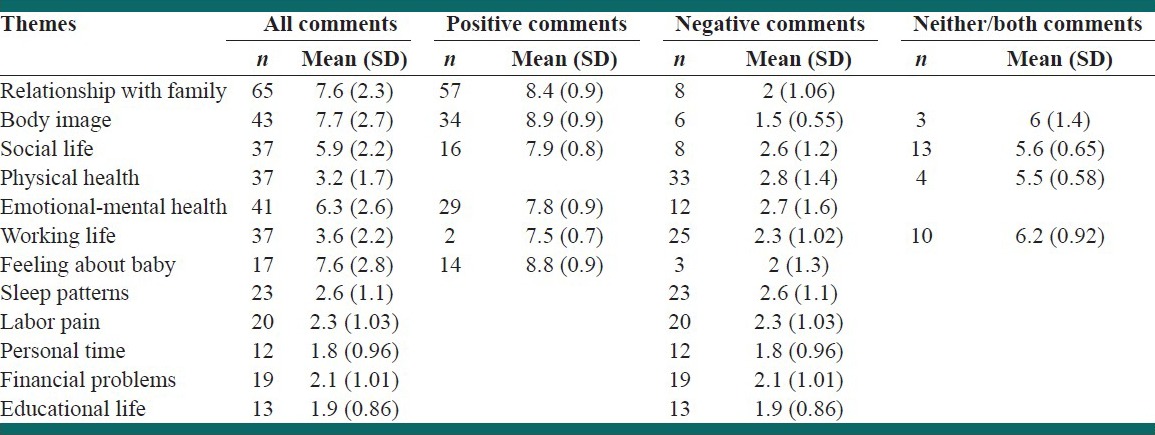

The comments were categorized into twelve ‘themes’. Table 2 demonstrates the frequency of comments under each theme and mean scores of the comments by themes. The themes of ‘labor pain’, ‘sleep pattern’, ‘personal time’, ‘educational life’ and ‘financial problems’ generated universally negative comments. Over 75% of the comments under each of the themes of ‘relationship with family’, ‘body image’ and ‘feeling about their baby’ were positive. Many of the other themes contained both positive and negative comments (e.g., social life and working life). Of 37 comments on ‘social life’, 16 were positive (e.g., ‘good relationship with friends’), 13 were neither/both, and eight were negative (e.g., ‘deficiency in social life’). Relationship with family included the most number of positive comments, whereas physical problems, working life, and sleep patterns included the most number of negative comments.

Table 2.

The themes, the frequency of comments under each theme, and the mean scores assigned to the comments for positive, negative, or neither/both

In Step 3, the comments included under the theme ‘relationship with family’ received the mean of highest weighted scores of 7.6 out of 20 (SD: 4.2). ‘Sleep patterns’ and ‘labor pain’ received the lowest weighted scores, respectively, 2.8 (SD: 1.2) and 2.9 (SD: 1.5) indicating that although many women considered sleep pattern and labor pain as negative aspects of their postnatal QoL, these were not considered as major factors.

Correlation between aggregate scores of comments and the primary scores was high (r = 0.68, P < 0.01). The mean of the secondary index score was 6.47 (95% CI: 5.60-7.33). The secondary MGI score was not significantly correlated with the primary score or the aggregate score of comments.

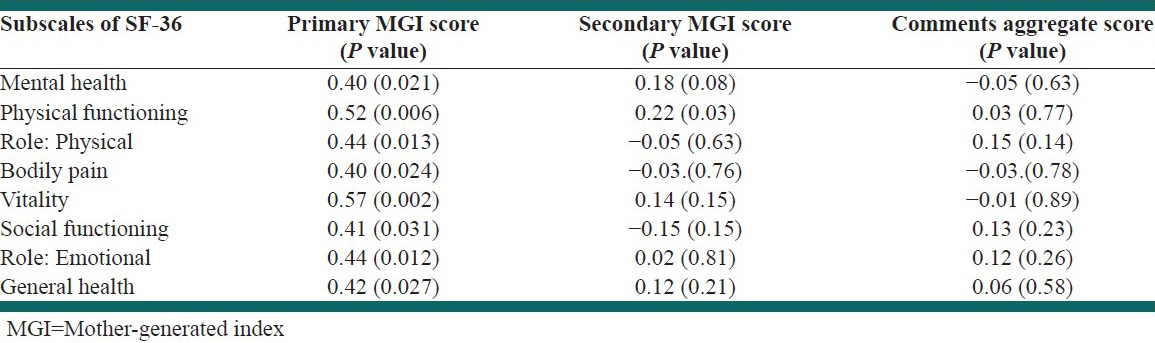

The mean score of physical function on the SF-36 was 52.81 (SD: 29.54), role limitation of physical function, 44.53 (SD: 37.9), role limitation of emotional function, 61.45 (SD: 37.56) vitality, 59.21 (SD: 24.11), mental health, 65.70 (SD: 21.18), body pain, 53.85 (SD: 23.63) and general health perception, 61.28 (SD: 24.59). The primary MGI scores were moderately and significantly correlated with all the subscales of the SF-36 (for all of subscales: Pearson r > 0.4; P < 0.0001). There were no such significant correlations between the SF-36 subscales and the secondary MGI scores (except for one subscale) and the aggregate scores of comments [Table 3].

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients between SF.36 subscale scores and primary MGI score, secondary MGI score, and aggregate score of comments

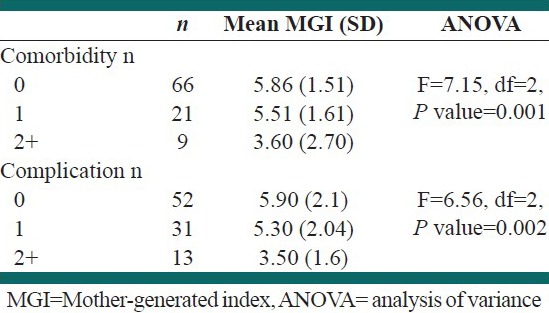

There was no significant association between the primary or secondary MGI score, and SF-36 scores for age, educational attainment, and the number of children. The analysis of findings about type of delivery showed that women after vaginal delivery scored slightly higher on the primary MGI score compared to mothers who experienced cesarean sections (5.6 vs. 4.8, 95% CI for mean difference: −0.16 to 1.6; P = 0.09). Also, women after vaginal delivery scored nonsignificantly higher on the SF-36 compared to mothers after cesarean section (60 vs. 56.2, 95% CI for mean difference: −12.69 to 5.63; P = 0.08). Women who had more than one comorbidity had significantly lower primary MGI scores than women without comorbidity [Table 4]. Also women who had experienced more than one postpartum medical complication had significantly lower primary MGI scores than women without complications [Table 4].

Table 4.

Mean score of Step 2 (primary index score) by number of comorbidities and complications

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have demonstrated that the MGI was a workable tool for assessing postnatal QoL. In this study, we assessed the validity of the tool in an Iranian context. This is the first study assessing postnatal QoL in Iran using a nongeneric, specific, and relevant index while documenting the limitations of the methods used. Our findings suggest that the MGI primary score and aggregate score of the comments may provide valid estimates of postnatal QoL in Iran. This conclusion is based on the high correlation between the ‘aggregate scores of comments’ and the primary MGI scores (suggesting internal consistency), and the significant correlations between the scores and the SF-36 scores (SF-36 was previously validated for use in Iran). We also noted that the MGI scores were significantly associated with the reported number of postnatal complications as well as patient comorbidities, suggesting criterion validity of the MGI scores [Figure 1 -2].

Figure 1.

Mother Generated Index questionnaire; Source: Symon A, MacDonald A, Ruta D. Postnatal Quality of Life Assessment: Introducing the Mother Generated Index. Birth 2002;29:40 6.

Figure 2.

An example demonstrating how the secondary Mother-generated index scores were calculated is shown in the additional File 2

The mean primary MGI score in our sample was 5.38 out of 10, whereas the average secondary index score was 6.47. This is similar to the findings from the original MGI study in Scotland,[24] in which the mean of the lowest quartile was 4.6 and that of the highest quartile was 8. In another study by Nagpal et al. in India, the overall mean primary index score was 3.6 and the average secondary index score was 2.9.[14] The overall higher scores in our study in comparison with other studies such as the Indian study may be related to the primarily positive nature of the areas cited by mothers or could reflect a higher QoL in our sample. Obviously, to generalize the findings to the Iranian population requires larger studies of representative samples.

We modified the way the weights for the comments were obtained and the secondary MGI scores were calculated, because of the difficulties experienced in the Step 3 scoring. These changes inevitably limit the comparability of our results to other settings. This may be a reason for the observed nonconcordance between the secondary MGI scores and the primary and aggregate scores in our study. Previous studies have also failed in demonstrating the validity of the secondary MGI scores.[24] As such, further work on the methods used for the estimation of the secondary scores is warranted. Still, it is noteworthy that the primary MGI score is the MGI's main indicator of QoL. Our study had other limitations: Our sample size of 96 reduced our power of observing other significant relationships.

The face validity of the Farsi version of the MGI questionnaire appeared to be satisfactory. The majority of the comments raised by the participants were clearly related to the experience of childbirth (e.g., comments relevant to ‘labor pain’, ‘feeling about baby’). Other comments were more linked to the experience of motherhood (e.g., ‘relationship with family’, ‘social life’ and ‘working life’). These suggest that the MGI is capable of generating comprehensive comments on important aspects of a woman's life as they are affected by giving birth and motherhood. As such, the MGI may provide health-care professionals with the opportunity of appreciating all aspects of a woman's life that are affected with the experience of having a baby.

Specific measures of QoL can enhance the detection of small, clinically important aspects in QoL related to specific areas of interest,[25] and as such, we believe that the use of the MGI is justified. Moreover, health-related QoL can be a good tool for reflecting service needs and thus, it is useful information for physicians.[26] For this reason, the MGI could be a very useful tool in clinical practice to provide optimal management of women's needs. Another interesting aspect of the MGI is its ability to capture other (nonhealth) aspects of women's lives that are affected by the experience of having a baby (e.g., ‘financial problems’). Such aspects are not measured by health-related QoL measurement tools such as SF-36. This may help the professionals and policy makers to have a more holistic understanding of the postnatal experiences of women.

In our study, women who underwent vaginal delivery scored higher (better) on both the SF-36 and MGI, although the differences were statistically nonsignificant. Cesarean section is not just a type of childbirth; it is also an operation, and like any form of surgery, can lead to problems resulting from hospitalization. This might justify differences observed between the two groups. In Iran, data published in 2005 suggested that cesarean section constituted 47% of all deliveries, 52% of the deliveries in Tehran, and 64% of the deliveries in the private sector,[27,28] and this may have increased in recent years. Other studies have reported even higher estimates of the rates of cesarean sections.[18,29,30] Our observed higher rates of cesarean sections may reflect the increasing trend over what was reported in 2005, or the peculiarities of the hospitals in which we sampled our participants.

CONCLUSIONS

In general, the Farsi version of the MGI performed well in an Iranian context and the findings suggest that it is a valid measure to assess QoL among postnatal women.

The MGI is an appropriate tool to assess holistic perinatal care for mothers. The instrument identifies the most important areas of a mother's life apart from the clinical aspects of care. This instrument can help to clarify the problems that may affect the mother's QoL that may not be immediately apparent to a doctor or midwife. As such, further assessment of its application to maternal care in Iran (and similar countries) is recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the hospitals, their staff, and the patients who willingly participated in the study. This article was extracted from the PhD thesis of RK. We are thankful to Zahra Negahban (ZN) and Elham Movahed for their valuable assistance in data collection and to ZN for assistance in analysis.

Additional material

Additional file 1:

Mother Generated Index. The MGI proforma.

Additional file 2:

Example. An example demonstrating how we calculated the Step 3 scores.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Bowden A, Fox-Rushby JA. A systematic and critical review of the process of translation and adaptation of generic health-related quality of life measures in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, South America. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:1289–306. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00503-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan M. The new subjective medicine: Taking the patient's point of view on health care and health. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1595–604. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Symon A, McGreavey J, Picken C. Validation of the Mother-Generated Index. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;110:865–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tully MP, Cantrill JA. The validity of the modified patient generated index: A quantitative and qualitative approach. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:509–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1008949809931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calman KC. Quality of life in cancer patients: An hypothesis. J Med Ethics. 1984;10:124–7. doi: 10.1136/jme.10.3.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glazener C, Abdalla M, Stroud P, Templeton A, Russell IT, Naji S. Postnatal maternal morbidity: Extent, causes, prevention and treatment. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:282–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill PD, Aldag JC, Hekel B, Riner G, Bloomfiled P. Maternal Postpartum Quality of Life Questionnaire. J Nurs Meas. 2006;14:205–20. doi: 10.1891/jnm-v14i3a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill PD, Aldag JC. Maternal perceived quality of life following childbirth. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36:328–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2007.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Symon A. A review of mothers’ prenatal and postnatal quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:38. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinpell RM. Whose outcomes. Patients, providers, or payers? Nurs Clin Nurs Am. 1997;32:513–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Symon AG, Dobb BR. An exploratory study to assess the acceptability of an antenatal quality-of-life instrument (the Mother-generated Index) Midwifery. 2008;24:442–50. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;140:111–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar R, Robson KM, Smith AM. Development of a self-administered questionnaire to measure material adjustment and material attitudes during pregnancy and after delivery. J Psychosom Res. 1984;28:43–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(84)90039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagpal J, Sengupta RD, Sinha S, Bhargava V, Sachdeva A, Bhartia A. An exploratory study to evaluate the utility of an adapted mother generated index (MGI) in assessment of postpartum quality of life in India. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:107. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg D. London: Oxford University Press; 1972. The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire: A technique for the identification and assessment of non-psychotic psychiatric illness. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boston: New England Medical Centre; 1994. The Health Institute. SF-12 Standard US Version. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torkan B, Parsay S, Lamyian M, Kazemnejad A, Montazeri A. Postnatal quality of life in women after normal vaginal delivery and caesarean section. BMC Preg and Child birth. 2009;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nowakowska-Głab A, Maniecka-Bryła I, Wilczyński J, Nowakowska D. Evaluation of antenatal quality of life of hospitalized women with the use of Mother-Generated Index-pilot study. Ginekologia Polska. 2010;81:521–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rashidian A, Yousefi Nooraie R. Development of a Farsi translation of the AGREE instrument, and the effects of group discussion on improving the reliability of the scores. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:676–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruta DA, Garratt AM, Leng M, Russell IT, MacDonald LM. A new approach to the measurement of quality of life: The Patient-Generated Index. Med Care. 1994;32:1109–26. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199411000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montazeri A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:875–82. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Symon A, MacDonald A, Ruta D. Postnatal Quality of Life Assessment: Introducing the Mother Generated Index. Birth. 2002;29:40–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:622–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacasse A, Bérard A. Validation of the nausea and vomiting of pregnancy specific health related quality of life questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:32–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostovar R, Rashidian A, Pourreza A, Rashidi B, Hantooshzadeh S, Ardebili H, et al. Developing criteria for Cesarean Section using the RAND appropriateness method. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tehran: Family Health Section; 2005. Ministry of Health and Medical Education. The Fertility Health Assessment Program. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shariat M, Majlesi F, Azari S, Mahmoodi M. Caesarean section in maternity hospitals in Tehran, Iran. J Iran Inst Health Sci Res. 2002;1:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alimohamadian M, Shariat M, Mahmoodi M, Ramezanzadeh F. The influence of maternal request on the elective caesarean section rate in maternity hospitals in Tehran, Iran. J Iran Inst Health Sci Res. 2003;2:133–9. [Google Scholar]