Abstract

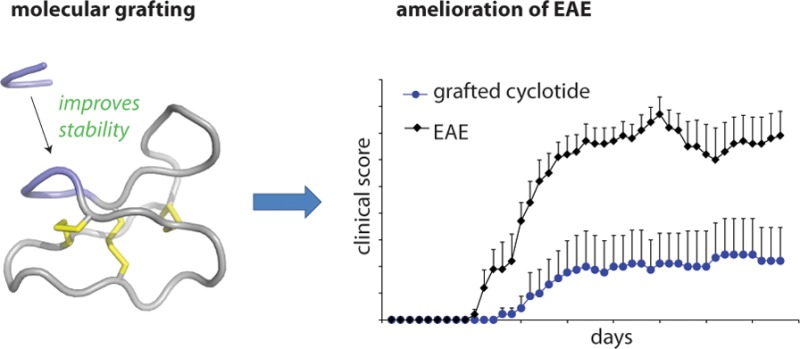

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS) and is characterized by the destruction of myelin and axons leading to progressive disability. Peptide epitopes from CNS proteins, such as myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), possess promising immunoregulatory potential for treating MS; however, their instability and poor bioavailability is a major impediment for their use clinically. To overcome this problem, we used molecular grafting to incorporate peptide sequences from the MOG35–55 epitope onto a cyclotide, which is a macrocyclic peptide scaffold that has been shown to be intrinsically stable. Using this approach, we designed novel cyclic peptides that retained the structure and stability of the parent scaffold. One of the grafted peptides, MOG3, displayed potent ability to prevent disease development in a mouse model of MS. These results demonstrate the potential of bioengineered cyclic peptides for the treatment of MS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) characterized by focal demyelinating lesions,1 where both the cellular and humoral arms of the immune system seem to play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of disease.2 The distinguishing pathological features of MS are localized, episodic, and progressive CNS demyelination, as well as axonal damage.3,4 There is now considerable experimental evidence suggesting that CNS myelin proteins might be relevant target autoantigens. Among these, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) stands out, not only because it is located on the outmost lamella of the myelin sheath, but also because it is expressed exclusively in CNS myelin.1,5

With the FDA approval of interferon beta-1b around 20 years ago, the landscape of MS therapeutics changed dramatically, giving further impetus to develop safer and more effective treatment strategies. Although there are currently several drugs approved for the treatment of MS and several others at late-stage clinical trial, the available therapeutics generally engage non-specific mechanisms of immune suppression, leaving patients susceptible to opportunistic pathogens.6 As an example of the inherent dangers in these approaches, a clinical trial of Natalizumab (Tysabri) led to the deaths of several participants from progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a viral infection of the brain.7 In view of the side effects of current therapeutics, antigen-specific strategies offer a promising alternative as they can potentially block the deleterious effects of specific immune components, while maintaining the ability of the immune system to clear nonself antigens.8 A novel and more specific approach to the treatment of MS would therefore be the design of antigen-specific therapies directed toward MOG.

Peptides have long been implicated as valuable compounds for the development of antigen-specific therapies because they offer many advantages over other modalities, including high activity and specificity. However, the clinical use of antigenic peptide sequences is limited because of their intrinsic in vivo instability. An emerging approach to overcome this challenge is to insert peptides into a scaffold of high stability, i.e., molecular grafting. In terms of peptide drug design, cyclotides9 represent a particularly attractive scaffold for molecular grafting because of their exceptional stability, which is attributed to their unique structural framework, comprising a cyclic backbone and a cystine knot motif (Figure 1a). There are now several successful examples showing that the cyclotide framework can be used to design drug leads for chronic diseases.10−15

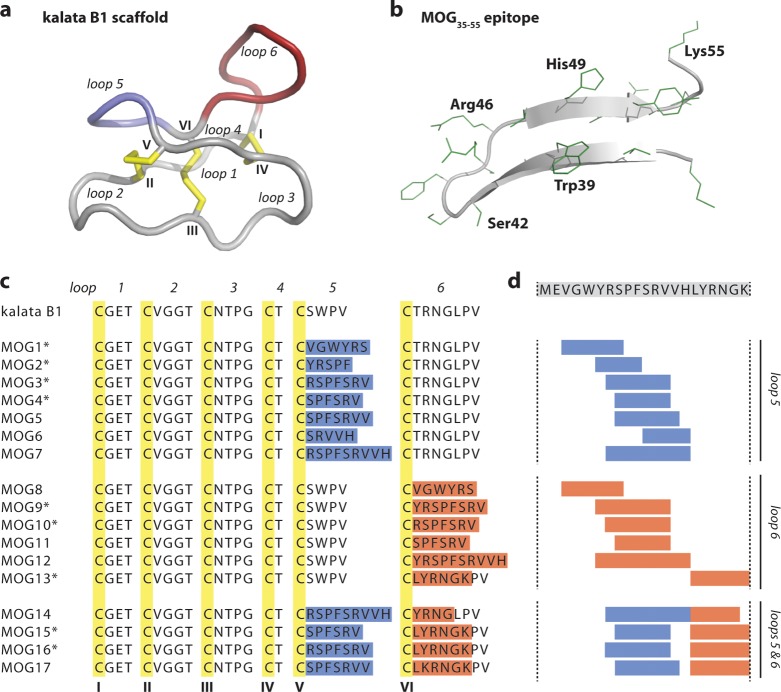

Figure 1.

Molecular grafting of antigenic peptides onto a cyclotide scaffold. (a) The cyclotide kalata B1 is stabilized by three conserved disulfide bonds (shown in yellow) and a head-to-tail cyclized backbone, which together form the cyclic cystine knot motif. The six conserved cysteines (numbered with roman numerals) divide the backbone into six loops, including loops 5 and 6 that are amenable to molecular grafting and colored in blue and red, respectively. (b) Native structure of the MOG35–55 bioactive epitope extracted from the three-dimensional structure of the entire MOG (myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein) protein. The epitope comprises two antiparallel β-sheets; selected residues are numbered in single letter code, and amino acid side chains are shown in green. (c) Aligned sequences of kalata B1 and novel grafted molecules MOG1–17. The six cysteine residues are highlighted in yellow, and the six loops are numbered. The grafted sequences in loops 5 and 6 are highlighted in blue and red, respectively. Grafted MOG peptides that adopted a native-like globular fold are marked with an asterisk. (d) The MOG35–55 bioactive epitope was grafted into the kalata B1 scaffold by dividing the full epitope sequence (shown on top) into smaller fragments and inserting them into either loop 5, loop 6 or loops 5 and 6.

In this study we generated several chimeric molecules consisting of a partial sequences of MOG grafted onto the prototypic cyclotide kalata B1, a peptide scaffold with high stability, and tested their potential to prevent disease development in an experimentally induced mouse model of MS. We identified a novel grafted molecule with potent in vivo activity, suggesting that our design approach may lead to improved antigen-specific therapeutics for the treatment of MS.

Results and Discussion

We employed molecular grafting as a drug design paradigm with the aim of stabilizing potentially therapeutic amino acid sequences from MOG to increase their therapeutic efficiency for successful delivery in vivo. This study describes the first attempt to use molecular grafting of a cyclotide framework (Figure 1a) aimed at generating long-lasting immunomodulation, thus setting up the foundation for the design of novel therapeutic approaches for MS and other autoimmune diseases.

Molecular Grafting of Antigen-Specific Peptides To Improve Stability

The goal of molecular grafting is to design novel molecules that retain both the activity of the antigen and the structure and stability of the scaffold onto which the epitope is grafted. MOG35–55 is a 21-amino-acid sequence of MOG with strong encephalitogenic activity that has previously shown potential as an antigen-specific target for tolerance induction strategies in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a mouse model of MS.5 Seventeen partial sequences of MOG35–55 (Figure 1b) were selected as epitopes and grafted into loops 5 and/or 6 of kalata B1 based on the structural similarity of the epitope and the part of the scaffold it was replacing (Figure 1c). The partial sequences were strategically chosen as overlapping fragments to provide complete coverage of MOG35–55; in this way, we were able to systematically explore and identify critical fragments of MOG35–55 that might elicit a specific immune response. The designed peptides were synthesized using established protocols.16

Our series of analogues provided a basis for investigating the structural plasticity of the kalata B1 framework and its ability to tolerate different foreign grafts. Peak dispersion and spectral quality of 1D 1H NMR spectra suggested that 9 of the 17 grafted peptides adopted a well-defined globular conformation (denoted with * in Figure 1c). In some cases, the kalata B1 scaffold accommodated significant variation; for example, MOG3 adopted a well-defined fold even though the modified loop 5, which contained a seven-residue epitope, was completely different in composition and length from that of the native scaffold. Although it appeared that some long sequence grafts were not tolerated, for example, both MOG7 (9-residue graft) and MOG12 (10-residue graft) did not adopt a well-defined conformation, a recent report of a well-folded grafted cyclotide showing oral activity against a bradykinin receptor involved a nine-residue graft,11 suggesting that sequence composition rather than length of the grafts has a larger impact on the fold of grafted cyclotides. Interestingly, some epitopes were tolerated when grafted in one loop but not in another; for example, MOG1 adopted a well-defined conformation but MOG8 did not. This observation is significant for future molecular grafting studies because it suggests that multiple loops should be considered when attempting to insert an active epitope into the cyclotide framework.

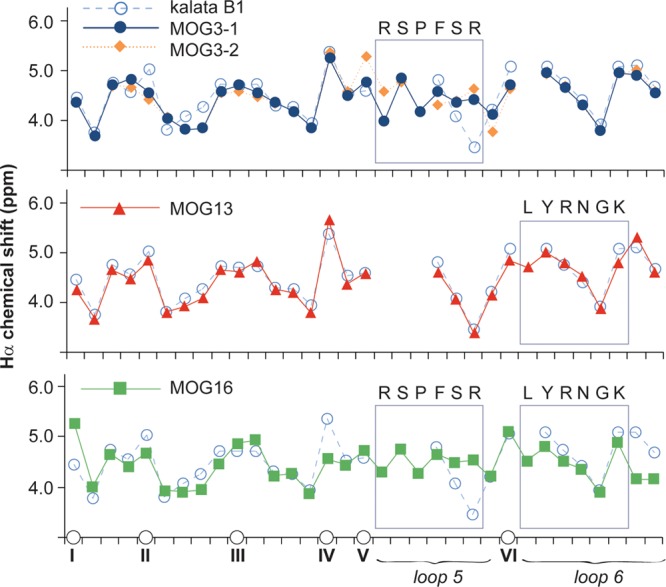

Detailed structural characterization of the grafted peptides was undertaken to determine whether the structural features of the scaffold are maintained in the grafted peptides. Specifically, two-dimensional homonuclear NMR was used to determine the Hα chemical shifts of the grafted peptides to obtain information on their three-dimensional structures. Figure 2 shows the Hα chemical shifts of three representative molecules (i.e., MOG3, MOG13, and MOG16), chosen on the basis of their grafted sequences, predicted structures, and range of in vivo activities (discussed below). As expected, the main differences in the structures of MOG3, MOG13, and MOG16 with respect to the native scaffold of kalata B1 are in or around the regions that were modified. Overall, the three-dimensional structures of the grafted peptides are essentially identical to the original scaffold molecule kalata B1, which is significant because the structural elements of kalata B1 underpin its remarkable stability.17

Figure 2.

Structural characteristics of MOG-grafted peptides. The Hα chemical shifts of MOG-grafted peptides and kalata B1 are shown. The positions of cysteines are indicated on the horizontal axis to align the sequence (non-cysteine residues are not shown for clarity). Two conformations for MOG3 (referred to as MOG3-1 and MOG3-2 in this figure) were observed. The different symbols used for each peptide are shown. Segments of the parent scaffold that have been grafted onto in loops 5 and 6 are boxed, and the sequences of the grafted epitopes are also shown.

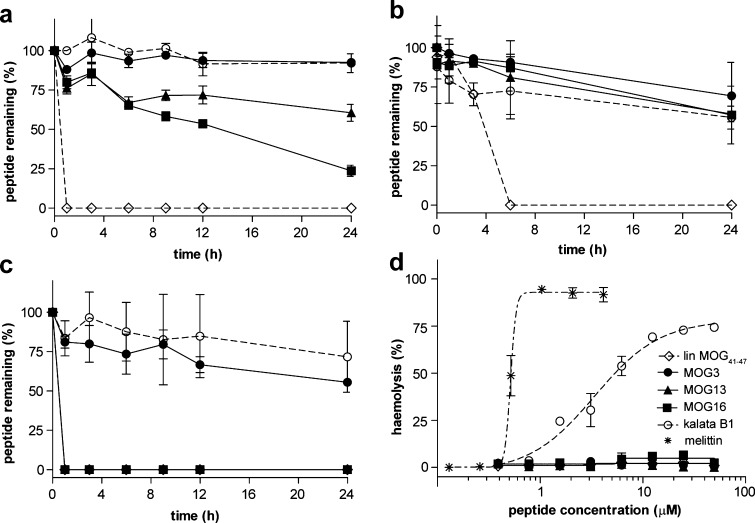

The grafted peptides were tested in a suite of stability assays (Figure 3a–c) to confirm that molecular grafting can be used as a general drug design approach for improving the stability of linear epitopes. The grafted peptides as well as the scaffold peptide kalata B1 and the linear epitope MOG41–47 were incubated in human serum, hydrochloric acid, or pancreatin (a mixture of enzymes that are present in the pancreas) and monitored over a 24-h period. In all assays, the scaffold peptide kalata B1 was very stable, whereas the linear epitope MOG41–47 alone was rapidly degraded. Specifically, in serum (Figure 3a), acid (Figure 3b), and pancreatin (Figure 3c), over 90%, 55%, and 70%, respectively, of kalata B1 was still detected after 24 h, while the linear epitope was completely degraded by that time. In general, the grafted peptides showed significantly improved stability over the linear epitope, suggesting that molecular grafting can be used to improve the stability of active peptide sequences. In particular, MOG3 showed the highest stability, which is significant because this peptide has the most potent in vivo activity of all of the grafted peptides (as described below). Additionally, we confirmed that the grafted peptides have no hemolytic activity. This contrasts with the mild hemolytic activity of the parent scaffold kalata B1 and the well-known strong hemolytic activity of the toxin peptide melittin used as a positive control (Figure 3d) and is a promising finding because it suggests that molecular grafting can be used to ‘tailor-make’ stable and potentially safe antigen-specific therapeutics for MS.

Figure 3.

Stability and hemolytic activity of MOG-grafted peptides. Stability of grafted peptides and controls over time (0–24 h) in (a) human serum, (b) hydrochloric acid, and (c) pancreatin as measured by the percentage of remaining intact peptide. (d) Hemolytic activity of grafted peptides was measured by the propensity of lysing human red blood cells. Mellitin, a strong hemolytic peptide from bee venom, was used as control. A legend for all peptides is shown.

Grafted Peptides Can Ameliorate Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis

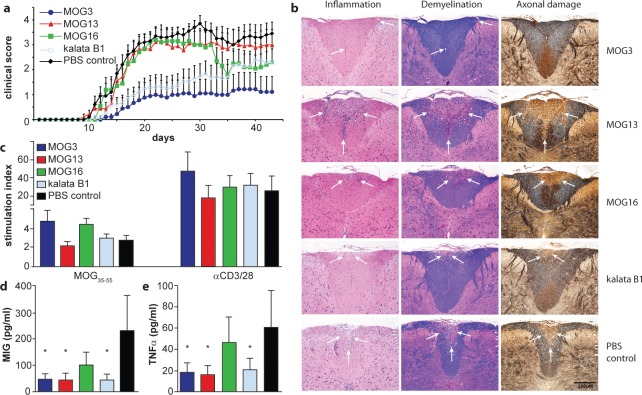

We selected seven grafted peptides (i.e., MOG3, MOG4, MOG9, MOG10, MOG13, MOG15, and MOG16) that retained the native structure of the scaffold as judged by 1D 1H NMR and/or homology modeling (Supplementary Figures 1–9) and assessed their activity in our EAE mouse model. We first confirmed that the grafted peptides did not have the potential to induce EAE in susceptible C57BL/6 mice. Using a standard EAE-induction protocol, none of the mice (n = 5) injected subcutaneously (sc) with 200 μg of MOG3 or kalata B1 developed any clinical or histological signs of EAE. We then tested the immunomodulatory effect of the MOG-grafted cyclotides in C57BL/6 mice immunized with MOG35–55. Mice were vaccinated with three successive sc injections of MOG-grafted cyclotides (200 μg) in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) at weekly intervals before EAE induction. Control mice were similarly treated but received either PBS or kalata B1 in IFA. Animals were assessed daily for clinical signs of EAE for a period of 43 days. Vaccination with MOG3 resulted in a significant reduction in the incidence and severity of EAE (Figure 4a). Only four out of nine mice treated with MOG3 developed signs of EAE, albeit very mild, as compared to 100% incidence in the control PBS group (n = 10). The cumulative clinical score of 28.1 ± 16.6 (mean ± SEM) (obtained from two separate experiments) and mean disease duration of 9.0 ± 4.1 observed in MOG3-vaccinated mice was significantly reduced (p < 0.01) compared to that of the PBS control group (cumulative score: 96.6 ± 7.1; disease duration: 29.1 ± 0.9). Interestingly, treatment of mice with kalata B1 resulted in some suppression of EAE (mean cumulative score 42.2 ± 13.0; p < 0.01), which might be related to the recently reported intrinsic immunosuppressant activity of kalata B1.18,19

Figure 4.

Activity of novel grafted peptides in vivo in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. (a) Clinical score of EAE mice after vaccination with MOG-grafted peptides (MOG3, dark blue line; MOG13, red line; MOG16, green line) and controls (kalata B1, light blue line; PBS, black line) was monitored. (b) The influence of MOG-grafted cyclotide vaccination on the formation of CNS inflammatory and demyelinating lesions was examined by histological studies of fixed tissue using hematoxylin/eosin, Luxol fast blue, and Bielshowsky silver staining. Regions of inflammation, demyelination, and axonal damage are highlighted by white arrows. (c) Proliferation of spleen cells in response to the encephalitogen MOG35–55 and stimulation by the polyclonal activators, anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. (d, e) Significantly reduced levels of the chemokine MIG (d) and TNFα (e) were demonstrated in non-stimulated spleen cell supernatants generated from animals treated with MOG3, MOG13, and kalata B1. * p < 0.05 compared to PBS control.

Compared to treatment with kalata B1 or MOG3, treatment with the other MOG-grafted cyclotides had no overall effect on the onset, incidence, and severity of the disease (Supplementary Figure 10), even though some late (day 35 onward) but nonsignificant amelioration of clinical signs was observed in MOG16-treated mice. From these results, it is clear that a partial sequence of MOG35–55 (i.e., MOG41–47; RSPVSRV) grafted onto loop 5 of the kalata B1 scaffold (i.e., MOG3) is sufficient to elicit a therapeutic effect.

To determine whether vaccination with the grafted peptides affected the pathology of EAE in treated mice, histological studies of the CNS were carried out to examine the extent of inflammation, demyelination, and axonal damage. The CNS of all mice treated with PBS, MOG13, or MOG16 showed extensive inflammatory lesions, characterized by mononuclear inflammatory cells, which were particularly florid in the cerebellum and spinal cord (Figure 4b). Luxol fast blue and Bielshowsky silver staining revealed marked myelin loss and severe axonal injury, respectively, particularly around the lesioned tissue in the brain, cerebellum, and spinal cord (Figure 4b). By contrast and as illustrated in Figure 4b for the spinal cord, histological analysis performed on the CNS of MOG3-treated mice revealed very little or no inflammatory lesions. This was associated with a dramatic decrease in the amount and extent of demyelination as well as damage and/or loss of axons. Seven out of nine such treated animals had little or no CNS lesions. Although kalata B1-treated mice displayed some improvement in disease severity, inflammatory lesions, demyelination, and axonal damage and/or loss were disseminated throughout the spinal cord (Figure 4b). Interestingly, for linear peptide MOG41–47, corresponding to the epitope grafted into MOG3, no disease suppression was observed and all treated mice displayed signs of inflammation, demyelination, and axonal damage similar to that observed in the PBS control group. Thus, vaccination with MOG3 but not with the other grafted peptides led to a substantial reduction of both clinical signs and histological lesions of EAE.

Grafted Peptides Modulate the Immune Response

Although a comprehensive understanding of the importance of B cell and T cell responses to the progression of EAE is still being formed, cell-based in vitro assays can provide some insight into how EAE is modulated in vivo by potential therapeutics. We first examined whether the suppression of EAE in mice vaccinated with the grafted peptides affected the production of specific antibodies to MOG. No significant differences in antibody titers between the PBS control, kalata B1- and MOG13-treated mice were determined with mean OD492 values for a 1:40 serum dilution of 0.46 ± 0.09, 0.62 ± 0.15, and 0.58 ± 0.17 for PBS-, kalata B1-, and MOG13-treated groups, respectively. Although the mean antibody titers for MOG3- and MOG16-treated mice were decreased (0.24 ± 0.05 and 0.28 ± 0.07, respectively) as compared to the control groups, these differences were not significant.

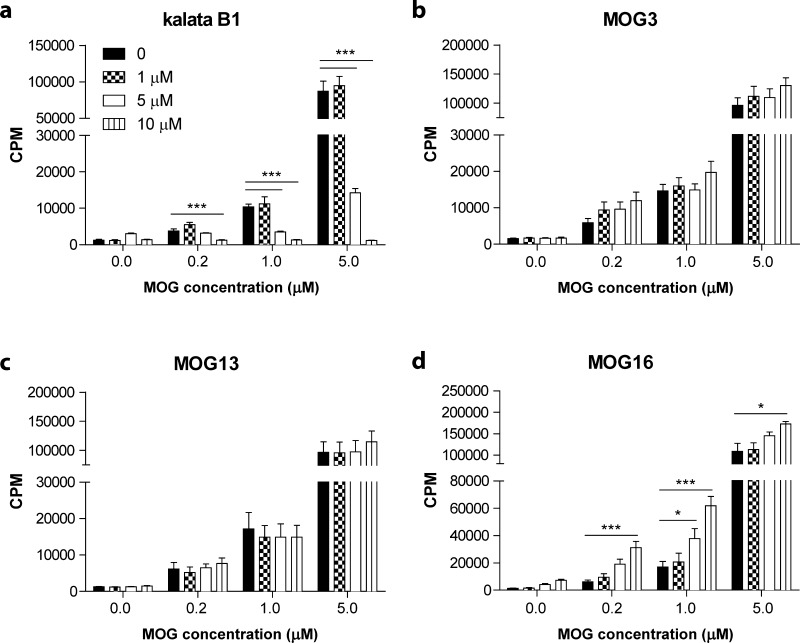

We tested whether the grafted peptides were able to affect the ability of T cells to proliferate using two experimental approaches. In the first approach, we tested the capacity of spleen cells from treated C57BL/6 mice to proliferate in response to the encephalitogen, MOG35–55. Stimulation indices from groups vaccinated with MOG3, MOG13, MOG16, kalata B1, and PBS were 4.6 ± 1.1, 2.1 ± 0.4, 4.4 ± 0.6, 2.9 ± 0.4, and 2.7 ± 0.5, respectively. Statistical analyses revealed that regardless of the treatment regimen, there were no differences in proliferative responses to MOG35–55, or following non-specific stimulation with anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28, between groups (Figure 4c). These results imply that treatment with the grafted peptides did not inhibit the activation of T cells. In the second approach, we tested the capacity of T cells specific for MOG to proliferate in response to the grafted peptides. Splenocytes from 2D2 TCR transgenic mice, which specifically recognize the MOG35–55 epitope,23 were cultured in the presence of increasing concentrations of MOG35–55 and either kalata B1 or the grafted peptides, MOG3, MOG13, or MOG16. No inhibitory effect was observed for either MOG3 or MOG13 at any of the concentrations tested, whereas the addition of MOG16 at high concentrations appeared to mildly enhance proliferative responses to MOG35–55 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of grafted peptides on the proliferation of spleen cells from 2D2 TCR transgenic mice. Proliferation of spleen cells from 2D2 TCR transgenic mice stimulated with different concentrations of MOG35–55 and incubated with (a) kalata B1, (b) MOG3, (c) MOG13, and (d) MOG16. Results show the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n = 3). * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

At concentrations higher than 1 μM, kalata B1 significantly inhibited the proliferation of 2D2 splenocytes stimulated with 1 μM or 5 μM MOG35–55 (p < 0.001). This result is consistent with the recently reported antiproliferative activity of kalata B1 on primary activated human lymphocytes.18 Another recent report further demonstrated that suppression of human T-lymphocyte proliferation by kalata B1 occurs through an interleukin 2-dependent mechanism.19 The reported immunosuppressive ability of kalata B1 may explain the partial suppression of EAE, even though this cyclotide did not contain any grafted sequences derived from MOG35–55.

Despite the unexpected activity of the kalata B1 scaffold itself, it is unlikely that any cyclotide will have activity in the EAE mouse model, since it has been observed that single amino acid mutants of kalata B1 have detrimental effects on its immunosuppressant activity.19 It is worth noting that although kalata B1 has potential as an immunosuppressant peptide, we showed in this study that it has mild hemolytic activity, suggesting that its therapeutic potential in its native form might be limited. With this in mind, MOG3 represents the most promising molecule in this study.

It is well established that the development of EAE is associated with the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by CNS-antigen specific T cells.20 Since the suppression of EAE following vaccination with MOG3 was not associated with a decrease in T cell reactivity to MOG, we investigated whether MOG-reactive T cells in protected animals might have switched to an anti-inflammatory T cell phenotype. Accordingly, conditioned media generated from in vitro stimulated and non-stimulated spleen cell cultures were assessed in cytokine bead array assays. A total of 15 cytokines were analyzed simultaneously, including, IL2, IL3, IL4, IL5, IL6, IL9, IL10, IL12p70, IL13, IFNγ, GM-CSF, KC, MCP1, MIG, and TNFα. We did not find any marked changes in cytokine content in MOG35–55- or CD3/28-stimulated supernatants between cyclotide and control animal groups. In contrast, significantly reduced levels of the chemokine MIG known to play a role in T cell trafficking and TNFα, a pro-inflammatory cytokine involved in the pathogenesis of EAE,21 were demonstrated in non-stimulated spleen cell supernatants generated from animals treated with MOG3, MOG13, and kalata B1 (Figure 4d and e). On the basis of this cytokine profile, it would appear that vaccination with MOG3 downregulates some of the pro-inflammatory responses involved in EAE pathogenesis.

Conclusion

There is now significant experimental and also some clinical findings suggesting that MOG constitutes an attractive target for early immune interventions in MS. Antigen-specific therapies directed toward MOG are not yet available but might play an important role in future therapies for MS, either alone or in combination with other specific or non-specific immuno-modulators. In this study, we used molecular grafting to design novel peptides that have improved therapeutic properties compared to those of linear MOG epitopes. One of the grafted peptides showed not only improved stability but also potent activity in the EAE mouse model of MS. Our results suggest that there is potential to develop safe and effective treatments for MS using cyclic peptide scaffolds.

Methods

Peptide Synthesis

All peptides were synthesized as described previously.12 Briefly, peptides were assembled manually on phenylacetamidomethyl resin (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and attached to a linker that generates a C-terminal thioester on HF cleavage.22 Following cleavage using HF with p-cresol and p-thiocresol as scavengers, the peptide was dissolved in 50% acetonitrile containing 0.05% TFA (trifluoroacetic acid) and lyophilized.

Peptide Purification and Analysis

Crude peptide mixtures were purified by RP (reversed-phase)-HPLC on a Phenomenex C18 column using a gradient of 0–80% B (Solvent A: water/0.05% (v/v) TFA; Solvent B: water/90% (v/v) acetonitrile/0.045% (v/v) TFA) over 80 min with the eluent monitored at 215 and 280 nm. Similar solvent conditions were used in subsequent purification steps. Analytical RP-HPLC and ESI-MS (electrospray mass spectrometry) was used to confirm purity. The linear reduced peptides were cyclized and oxidized by incubating in 0.1 M NH4HCO3 (pH 8.5)/propan-2-ol (50:50, v/v) with 1 mM reduced glutathione overnight at RT and purified by RP-HPLC.

NMR Experiments

Samples were prepared in 90% (v/v) H2O and 10% (v/v) D2O to a concentration of ∼0.5 mM. Spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 500 or a Bruker Avance 600 NMR spectrometer at temperatures from 290 to 310 K. For TOCSY experiments, the mixing time was 80 ms, and for NOESY the mixing time was 100–300 ms. Spectra were analyzed using CCPNMR.

Stability Assays

Lyophilized peptides were dissolved in Milli-Q water to make 2 mg mL–1 stock solutions. All experiments were conducted in triplicate and analyzed using RP-HPLC.

Pancreatin Stability Assay

A 100 μg mL–1 solution of Pancreatin (Sigma) was prepared in PBS. This mixture contains many enzymes including amylase, trypsin, lipase, ribonuclease, and protease. Equal volume of enzyme was added to peptide to give a final concentration of 1 mg mL–1 peptide and 50 μg mL–1 of pancreatin. Samples were incubated at 37 °C, and 10 μL aliquots were quenched with 90 μL of 4% (v/v) TFA at selected time points: 1 min, 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 9 h, 12 h, and 24 h. All peptides were also incubated in PBS as a control and analyzed at 1 min and 24 h time point.

Serum Stability

Human pooled serum (Sigma) was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min to remove the lipid layer. The remainder of the serum was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, and then 25 μL of 1 mg mL–1 peptide solution was added to 225 μL of serum and incubated at 37 °C for different amounts of time: 1 min, 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 9 h, 12 h, and 24 h. Aliquots of 90 μL of serum/peptide solution were quenched twice with 90 μL of 15% TCA (trichloroacetic acid) solution. The mixture was stored at 4 °C and centrifuged for 15 min at 14,000 rpm, and the supernatant was analyzed using RP-HPLC. Test peptides were dissolved in water and incubated at 37 °C for the duration of the experiment and analyzed at 0 and 24 h as a control.

Hemolysis

A 2-fold serial dilution was prepared of each test peptide to give solutions with the following approximate concentrations of the peptides: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125, 0.0625, 0.0313, and 0.016 mg mL–1. Melittin solution (20 μM) was diluted in 2-fold dilutions to give 6 solutions as well. A 1% triton X-100 solution was used to determine maximum hemolysis as a positive control. A 0.25% RBC solution was prepared after repeated wash steps where a few drops of blood in 1 mL of PBS was centrifuged at 4000 rpm. Using a 96-well round-bottom flask, 20 μL of the test peptides and controls was added to 100 μL of red blood cell solution and incubated at 37 °C. After 1 h of incubation and centrifugation for 5 min at 150 RCF, 100 μL of supernatant was transferred into a 96-well flat bottom plate, and the absorbance was measured at 415 nm using a UV–vis spectrometer.

Acid Hydrolysis

Equal volume of test peptides and 1 M HCl were incubated at 37 °C for the duration of the experiment. Aliquots of 10 μL were removed at selected time points 1 min, 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, and 24 h and quenched with 1% (v/v) NaOH solution. Samples were analyzed using RP-HPLC.

Mice

C57BL/6 mice (10–16 weeks old) and MOG35–55-specific T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic (2D2) mice23 were bred and maintained in the Monash University Animal Services facilities. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Australian code of practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes (NHMRC, 1997), after approval by the Monash University Animal Ethics committee (Clayton/Melbourne, Australia).

Induction and Clinical Assessment of EAE

A total of 200 μg of the encephalitogenic peptide MOG35–55 (MEVGWYRSPFSRVVHLYRNGK; GL Biochem, Shanghai, China) emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) (Sigma) supplemented with 4 mg mL–1Mycobacterium tuberculosis (BD) was injected subcutaneously into the flanks. Mice were then immediately injected intravenously with 350 ng of pertussis vaccine (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, USA) and again 48 h later.5,24−27 Animals were monitored daily, and neurological impairment was quantified on an arbitrary clinical scale: 0, no detectable impairment; 1, flaccid tail; 2, hind limb weakness; 3, hind limb paralysis; 4, hind limb paralysis and ascending paralysis; 5, moribund or deceased.28,29 Under recommendation of the animal ethics committee, mice were humanely killed after reaching a clinical score of 4.

Vaccination with Grafted Cyclotide MOG Peptides

A 200 μg portion of the various MOG-grafted cyclotides was emulsified with an equal volume of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) (Difco) and injected subcutaneously in the upper flanks (100 μL divided equally) 3 weeks prior to the encephalitogenic challenge. This was followed by two more injections at weekly intervals (200 μg/IFA/100 μL).

Histopathology and Assessment of Inflammation, Demyelination, and Axonal Damage

At the completion of the experiments, mice were humanely killed, their blood was collected (for subsequent antibody determination), and brain and spinal cord carefully were removed, prior to immersion in a 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution. Segments of brain, cerebellum, and spinal cord were embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin, Luxol fast blue, and Bielshowsky silver stain for evidence of inflammation, demyelination, and axonal damage, respectively. Semiquantitative histological evaluation for inflammation and demyelination was performed and scored in a blind fashion as follows: 0, no inflammation; 1, cellular infiltrate only in the perivascular areas and meninges; 2, mild cellular infiltrate in parenchyma; 3, moderate cellular infiltrate in parenchyma; and 4, severe cellular infiltrate in parenchyma.30,31

MOG-Specific Antibody Determination

Antibody activity to rMOG1–121 and MOG35–55 in mouse sera was measured by ELISA, as previously described.32 Briefly, serum was collected at the end of the experiments and tested by ELISA with rMOG1–121 and MOG35–55 peptide-coated plates (Maxisorp, Nunc). Methods for the production of antibodies and recombinant proteins are provided in the Supporting Information.

T Cell Proliferation and Cytokine Production

For proliferation assays examining the effect of MOG35–55 or anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 on treated mice, spleens were taken from mice humanely killed 32–46 days after MOG35–55 immunization. Cells were gently dispersed through a 70 μm nylon mesh (BDinto a single cell suspension, red blood cells lysed, washed and cultured at 2.5 × 106 cells mL–1 in complete medium (RPMI 1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Sigma), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U mL–1 of penicillin, 100 μg mL–1 of streptomycin, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate). Then 200 μL of cell suspensions was then added to 96-well microtiter plates either alone, with MOG35–55 (20 μg mL–1) or anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 (20 μg mL–1 each) and incubated for 66 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Next, 10 μL of [3H]thymidine (1 μCi/well; Amersham, Australia) was added to each well for the last 18 h. Plates were harvested onto glass fiber filters, and a drop of Microscint Scintillant (Perkin-Elmer) was added to each well. Counts were read using a Top Count NXT Scintillation Counter (Perkin-Elmer). Presented values are the mean of three wells.

For proliferation assays examining the inhibitory effect of grafted MOG peptides, spleen cells from 2D2 TCR transgenic mice were prepared as described above. Cells were then cultured in the presence of media alone or varying concentrations of MOG35–55 (0.2 μM, 1 μM, 5 μM) and grafted cyclotides (1 μM, 5 μM, 10 μM) to a final volume of 200 μL. Proliferative responses were measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation as described above.

For cytokine assays, 2 mL of cells (2.5 × 106 cells mL–1) from spleens isolated 32–46 days after immunization were added to 24-well plates either alone or with MOG35–55 (10 μg mL–1) or with anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 (20 μg mL–1 each). Supernatants were collected at 48 and 72 h. Quantitation of mouse cytokine content incorporating Th1, Th2 cytokines and chemokines (IFNγ, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, GM-CSF, KC, MCP-1, MIG, and TNFα) were simultaneously determined using a multiplexed bead assay (Cytometric Bead Array Flex sets [CBA]) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol (Becton Dickinson). Acquisition of 4500 events was performed using a FACScanto II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, USA) and Diva software, and data were analyzed and fitted to a 4-parameter logistic equation using the FCAP array software (Soft Flow, Pécs, Hungary). Minimum detection levels of each cytokine were (in pg mL–1): IFNγ, 5.2; IL-2, 1.5; IL-3, 4.2; IL-4, 0.8; IL-5, 4.8; IL-6, 6.5; IL-9, 10.5; IL-10, 16.4; IL-12p70, 9.2; IL-13, 7.3; GM-CSF, 9.9; KC, 16.2; MCP-1, 29; MIG, 11.4; and TNFα, 17.1.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5.03 (GraphPad Software). Experimental groups were compared using a One-Way ANOVA with Dunnett posthoc test. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

The studies described herein were supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC #301093), ARC (DP0984955), and the Eva and Les Erdi AUSiMED Fellowship in Neurological Diseases. D. Craik is a NHMRC Professorial Fellow (APP1026501) and C. Wang is a NHMRC Early Career Fellow (NHMRC #536578). The authors also wish to thank Adrian and Michelle Frick for their generous support. Work on immunosuppressive peptides in the laboratory of C. Gruber is funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF-P24743).

Supporting Information Available

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

∥ These authors contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ewing C.; Bernard C. C. (1998) Insights into the aetiology and pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Immunol. Cell Biol. 76, 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C. C.; Kerlero de Rosbo N. (1992) Multiple sclerosis: an autoimmune disease of multifactorial etiology. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 4, 760–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuki M.; Ayers M. M.; Bernard C. C.; Orian J. M. (2001) Axonal degeneration is an early pathological feature in autoimmune-mediated demyelination in mice. Microsc. Res. Tech. 52, 731–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers M. M.; Hazelwood L. J.; Catmull D. V.; Wang D.; McKormack Q.; Bernard C. C.; Orian J. M. (2004) Early glial responses in murine models of multiple sclerosis. Neurochem. Int. 45, 409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C. C.; Johns T. G.; Slavin A.; Ichikawa M.; Ewing C.; Liu J.; Bettadapura J. (1997) Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein: a novel candidate autoantigen in multiple sclerosis. J. Mol. Med. 75, 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghikia A.; Hohlfeld R.; Gold R.; Fugger L. (2013) Therapies for multiple sclerosis: translational achievements and outstanding needs. Trends Mol. Med. 19, 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson W. H.; Genovese M. C.; Moreland L. W. (2001) Demyelinating and neurologic events reported in association with tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonism: by what mechanisms could tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists improve rheumatoid arthritis but exacerbate multiple sclerosis?. Arthritis Rheum. 44, 1977–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman L. (2006) The coming of age for antigen-specific therapy of multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 13, 793–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craik D. J. (2006) Seamless proteins tie up their loose ends. Science 311, 1563–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan L. Y.; Gunasekera S.; Henriques S. T.; Worth N. F.; Le S. J.; Clark R. J.; Campbell J. H.; Craik D. J.; Daly N. L. (2011) Engineering pro-angiogenic peptides using stable, disulfide-rich cyclic scaffolds. Blood 118, 6709–6717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. T.; Rowlands D. K.; Wong C. H.; Lo T. W.; Nguyen G. K.; Li H. Y.; Tam J. P. (2012) Orally active peptidic bradykinin B1 receptor antagonists engineered from a cyclotide scaffold for inflammatory pain treatment. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 51, 5620–5624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekera S.; Foley F. M.; Clark R. J.; Sando L.; Fabri L. J.; Craik D. J.; Daly N. L. (2008) Engineering stabilized vascular endothelial growth factor-A antagonists: synthesis, structural characterization, and bioactivity of grafted analogues of cyclotides. J. Med. Chem. 51, 7697–7704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasen R.; Daly N. L.; Wulff B. S.; Andresen T. L.; Conde-Frieboes K. W.; Craik D. J. (2012) Design, synthesis, structural and functional characterization of novel melanocortin agonists based on the cyclotide kalata B1. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 40493–40501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thongyoo P.; Bonomelli C.; Leatherbarrow R. J.; Tate E. W. (2009) Potent inhibitors of beta-tryptase and human leukocyte elastase based on the MCoTI-II scaffold. J. Med. Chem. 52, 6197–6200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboye T. L.; Ha H.; Majumder S.; Christ F.; Debyser Z.; Shekhtman A.; Neamati N.; Camarero J. A. (2012) Design of a novel cyclotide-based CXCR4 antagonist with anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 activity. J. Med. Chem. 55, 10729–10734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. J.; Craik D. J. (2010) Native chemical ligation applied to the synthesis and bioengineering of circular peptides and proteins. Biopolymers 94, 414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. K.; Hu S. H.; Martin J. L.; Sjogren T.; Hajdu J.; Bohlin L.; Claeson P.; Göransson U.; Rosengren K. J.; Tang J.; Tan N. H.; Craik D. J. (2009) Combined X-ray and NMR analysis of the stability of the cyclotide cystine knot fold that underpins its insecticidal activity and potential use as a drug scaffold. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10672–10683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gründemann C.; Koehbach J.; Huber R.; Gruber C. W. (2012) Do plant cyclotides have potential as immunosuppressant peptides?. J. Nat. Prod. 75, 167–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gründemann C.; Thell K.; Lengen K.; Garcia-Käufer M.; Huang Y.-H.; Huber R.; Craik D. J.; Schabbauer G.; Gruber C. W. (2013) Cyclotides suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation by an interleukin 2-dpendent mechanism. PLoS One 8, e68016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens T. (2003) The enigma of multiple sclerosis: inflammation and neurodegeneration cause heterogeneous dysfunction and damage. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 16, 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson L. B.; Kuchroo V. K. (1996) Manipulation of the Th1/Th2 balance in autoimmune disease. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 8, 837–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson P. E.; Muir T. W.; Clark-Lewis I.; Kent S. B. (1994) Synthesis of proteins by native chemical ligation. Science 266, 776–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E.; Pagany M.; Weiner H. L.; Linington C.; Sobel R. A.; Kuchroo V. K. (2003) Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific T cell receptor transgenic mice develop spontaneous autoimmune optic neuritis. J. Exp. Med. 197, 1073–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albouz-Abo S.; Wilson J. C.; Bernard C. C.; von Itzstein M. (1997) A conformational study of the human and rat encephalitogenic myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptides 35–55. Eur. J. Biochem. 246, 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hvas J.; McLean C.; Justesen J.; Kannourakis G.; Steinman L.; Oksenberg J. R.; Bernard C. C. (1997) Perivascular T cells express the pro-inflammatory chemokine RANTES mRNA in multiple sclerosis lesions. Scand. J. Immunol. 46, 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns T. G.; Bernard C. C. (1997) Binding of complement component Clq to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein: a novel mechanism for regulating CNS inflammation. Mol. Immunol. 34, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon K. K.; Piddlesden S. J.; Bernard C. C. (1997) Demyelinating antibodies to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein and galactocerebroside induce degradation of myelin basic protein in isolated human myelin. J. Neurochem. 69, 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Marino M. W.; Wong G.; Grail D.; Dunn A.; Bettadapura J.; Slavin A. J.; Old L.; Bernard C. C. (1998) TNF is a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine in autoimmune-mediated demyelination. Nat. Med. 4, 78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin A.; Ewing C.; Liu J.; Ichikawa M.; Slavin J.; Bernard C. C. (1998) Induction of a multiple sclerosis-like disease in mice with an immunodominant epitope of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Autoimmunity 28, 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettadapura J.; Menon K. K.; Moritz S.; Liu J.; Bernard C. C. (1998) Expression, purification, and encephalitogenicity of recombinant human myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. J. Neurochem. 70, 1593–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda Y.; Okuda M.; Bernard C. C. (2002) The suppression of T cell apoptosis influences the severity of disease during the chronic phase but not the recovery from the acute phase of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 131, 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa M.; Koh C. S.; Inaba Y.; Seki C.; Inoue A.; Itoh M.; Ishihara Y.; Bernard C. C.; Komiyama A. (1999) IgG subclass switching is associated with the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis induced with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide in NOD mice. Cell. Immunol. 191, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.