Abstract

Systemic autoimmunity is a complex disease process that results from a loss of immunological tolerance characterized by the inability of the immune system to discriminate self from non-self. In patients with the prototypic autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), formation of autoantibodies targeting ubiquitous nuclear antigens and subsequent deposition of immune complexes in the vascular bed induces inflammatory tissue injury that can affect virtually any organ system. Given the extraordinary genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of SLE, one approach to the genetic dissection of complex SLE is to study monogenic diseases, for which a single gene defect is responsible. Considerable success has been achieved from the analysis of the rare monogenic disorder Aicardi–Goutières syndrome (AGS), an inflammatory encephalopathy that clinically resembles in-utero-acquired viral infection and that also shares features with SLE. Progress in understanding the cellular and molecular functions of the AGS causing genes has revealed novel pathways of the metabolism of intracellular nucleic acids, the major targets of the autoimmune attack in patients with SLE. Induction of autoimmunity initiated by immune recognition of endogenous nucleic acids originating from processes such as DNA replication/repair or endogenous retro-elements represents novel paradigms of SLE pathogenesis. These findings illustrate how investigating rare monogenic diseases can also fuel discoveries that advance our understanding of complex disease. This will not only aid the development of improved tools for SLE diagnosis and disease classification, but also the development of novel targeted therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: Aicardi–Goutières syndrome, autoimmunity, nucleic acid sensing, systemic lupus erythematosus, type I interferon

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) – a prototypic autoimmune disease

SLE is a chronic relapsing autoimmune disease with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations ranging from subtle symptoms to fatal multi-organ failure. The disease process is initiated by loss of self-tolerance resulting in the production of autoantibodies. The deposition of these autoantibodies as immune complexes in various tissues followed by inflammation and tissue injury is regarded as a key mechanism in SLE pathogenesis 1. The systemic nature of the disease is reflected by fevers, fatigue and weakness, as well as multiple organ manifestations. These include arthritis and cutaneous manifestations, which occur in most patients, as well as glomerulonephritis, central nervous system involvement and perturbations of the haematopoietic system 1.

From a clinical perspective, early diagnosis of SLE remains challenging due to its heterogeneous presentation, with no single test being sufficiently specific and sensitive to be diagnostic. Until today, the diagnosis of SLE is based on classification criteria which were defined by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 30 years ago 2–3. Thus, SLE is diagnosed if at least four of the 11 criteria develop at one time or individually over any period of observation 2–3. However, owing to the often insidious onset and great clinical variability, it may take up to several years until the diagnosis can be established 4. Although the ACR criteria play only an ancillary role in the clinical setting, they constitute the gold standard for inclusion of patients in clinical trials or genome-wide association studies.

In European countries the prevalence of SLE ranges from 20 to 40 per 100 000 5. Prevalence varies considerably across different ethnic groups and is two- to fourfold higher among African Americans, Hispanics and Asians compared to Caucasians 5. SLE usually affects young women and shows a marked gender disparity, with a female-to-male ratio of 9:1. Paediatric-onset SLE represents 10–20% of all SLE cases and is associated with higher disease severity than adult-onset SLE 6.

Although improvements in medical care have dramatically enhanced the survival of SLE patients, mortality or major reductions of quality-of-life due to severe internal organ damage, co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease or toxic effects of therapy remain a major concern.

Genetic basis of SLE

There is substantial evidence for a strong genetic component of SLE. SLE shows familial aggregation, with an estimated sibling recurrence risk of 15. In addition, the concordance rate among monozygotic twins (approximately 35%) is 10-fold higher compared to dizygotic twins (approximately 3%) 7. The incomplete concordance of disease expression in monozygous twins also supports the role of non-genetic factors in the disease aetiology. Environmental factors implicated in SLE include ultraviolet (UV) light, viral infection and certain drugs 1,8.

The genetic basis for susceptibility to SLE has been subject to intense investigation, both in humans and in animal models. Candidate gene or genome-wide association studies have led to the identification of more than 20 risk loci 10–11. The implicated genes encode proteins important for adaptive immunity and autoantibody production [human leucocyte antigen (HLA) class II alleles, CTLA4, PTPN22, BLK, BANK1, TNFS4], cell disposal and immune-complex processing (C1q, C2, C4, FCGR2A, FCGR3A), proteins with roles in innate immunity relating to leucocyte adhesion (ITGAM) and cytokine signalling pathways (TNFAIP3, TNIP1, STAT4, IRF5, IRAK1, IFIH1, TREX1, CSK) 10,11.

Collectively, these findings highlight the complexity and heterogeneity of SLE pathophysiology and provide a framework which will allow further dissection of genetically determined primary disease pathways. However, they also raise important questions with respect to the transfer of genetic findings into an understanding of disease pathology. Indeed, finding causative relationships between genotypic and phenotypic variation and translating this knowledge into clinically relevant concepts continues to be an important task.

Lessons learned from monogenic disease

In contrast to multi-factorial polygenic diseases, the clinical phenotype and the associated molecular pathology of a monogenic disorder can be attributed to the pleiotropic effects of a single gene defect. In fact, the elucidation of rare monogenic autoimmune syndromes such as autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1 (APS1) caused by mutations in autoimmune regulator (AIRE) and the immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome due to mutations in forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3) have contributed substantially to our understanding of mechanisms underlying central and peripheral tolerance 13.

Recent studies on rare Mendelian disorders associated with lupus phenotypes have provided novel insights into disease mechanisms that are also highly relevant to complex SLE. Aicardi–Goutières syndrome (AGS) is an autosomal recessive inflammatory encephalopathy that clinically mimics in-utero-acquired viral infection despite the absence of detectable viral infection 14. AGS patients commonly feature signs that are also observed in patients with SLE, including activation of type I interferon (IFN), cutaneous chilblain lesions, arthritis, anti-nuclear antibodies, reduced complement and haematological abnormalities 15,16. AGS is caused by bi-allelic mutations in at least six genes encoding enzymes involved in the metabolism of intracellular nucleic acids. These include 3′ repair exonuclease 1 (TREX1; DNASE III) 18, the three subunits of the ribonuclease H2 (RNASEH2A, RNASEH2B, RNASEH2C) 19, SAM domain and HD domain-containing 1 (SAMHD1) 20 and the RNA-specific adenosine deaminase (ADAR1) 21. Heterozygous mutations in TREX1 cause additional inflammatory phenotypes characterized by autoimmunity, including autosomal-dominant familial chilblain lupus, a monogenic form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and autosomal-dominant retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leucodystrophy 22–25. In addition, dominant AGS can be caused by heterozygous de-novo TREX1 mutations 26–27, while familial chilblain lupus has also been described in a family with SAMHD1 mutation 28. Moreover, it was shown that rare TREX1 variants confer a high risk for complex SLE 29, a finding that has been confirmed in patients with neuropsychiatric SLE as well as in a large multi-ethnic SLE cohort 30–31. These findings not only underscore the contribution of rare gene variants to the genetic susceptibility to complex SLE, but also illustrate how studies on monogenic diseases can advance our understanding of complex disease. Thus, AGS can be viewed as a model disease for systemic autoimmunity. This also implies a possible role of the other AGS genes as risk factors of complex SLE.

Functional properties of TREX1, RNase H2, SAMHD1 and ADAR1

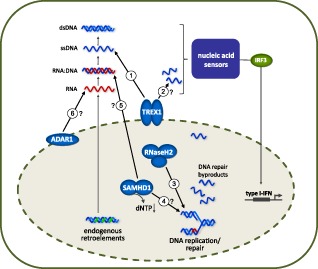

Progress in understanding the cellular and molecular functions of the AGS-associated genes has led to the identification of a number of novel pathways of the intracellular nucleic acid metabolism (Fig. 1). The cytosolic 3′–5′ exonuclease TREX1 degrades ssDNA originating from apoptotic DNA damage or DNA replication stress 32,33. Chronic DNA damage checkpoint activation in TREX1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts was shown to be accompanied by the appearance of a short ssDNA species within the cytosol 34. Sequence analysis of cytosolic ssDNA from TREX1-deficient mouse cells has demonstrated a significant increase in reverse-transcribed DNA derived from endogenous retro-elements 35, highly repetitive sequence elements which account for almost half of the mammalian genome. Endogenous retro-elements such as L1 elements, long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons and endogenous retroviruses represent the remnants of ancient infections with exogenous retroviruses. They are transcriptionally active and potentially capable of retrotransposition via a reverse-transcribed RNA-intermediate 36–37. In contrast to the human genome, where retrotransposition events are rare, the mouse genome harbours highly active endogenous retro-elements such as intracisternal A-particle (IAP) elements that can retrotranspose autonomously 38. Interestingly, the loss of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-dependent sensing of retro-element-derived nucleic acids in mice results in autoimmunity and leukaemia, further highlighting the potential threat caused by uncontrolled retro-element activity 39–40.

Figure 1.

Functional properties of three prime repair exonuclease 1 (TREX1), ribonuclease H2 (RNase H2), SAM domain and HD domain-containing protein 1 (SAMHD1) and adenosine deaminase acting on RNA 1 (ADAR1) within the intracellular nucleic acid metabolism. TREX1 degrades cytosolic ssDNA arising during reverse transcription of endogenous retro-elements (1) and during replication stress (2). Loss of TREX1 function results in accumulation of cytosolic DNA. RNase H2 removes single ribonucleotides from DNA (3). RNase H2 deficiency induces genome instability associated with DNA damage signalling. The triphosphohydrolase SAMHD1 down-regulates the intracellular dNTP pool required for DNA synthesis. Absence of SAMHD1 may contribute to inappropriately increased DNA synthesis (4) or promote reverse transcription of endogenous retro-elements (5). The RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1 deaminates adenosine to inosine of RNA species that may derive from endogenous retro-elements (6) or microRNAs. This modification is thought to alter the immune-activating properties of the edited RNA species or to interfere with transcriptional control of type I interferon (IFN). Functional impairment of TREX1, RNase H2, SAMHD1 or ADAR1 results in quantitative or qualitative imbalances within the intracellular nucleic acid homeostasis. Inadequately accumulated nucleic acids are recognized as danger signals by innate immune sensors that activate type I IFN leading to inflammation and autoimmunity.

TREX1-deficient mice develop an autoimmune-mediated myocarditis 41. This phenotype is dependent upon type I IFN activation initiated in non-haematopoietic cells, and concomitant genetic inactivation of the type I IFN system results in complete rescue of the phenotype 35–42. Notably, the autoimmune myocarditis of TREX1-deficient mice, although not responsive to the nucleoside analogue azidothymidine, was shown to be ameliorated by anti-retroviral therapy targeting the retroelement-encoded reverse transcriptase 35–43. However, whether unabated retro-element activity is also the primary cause of autoimmunity in patients with AGS or SLE remains to be investigated.

The heterotrimeric RNase H2 degrades RNA within an RNA : DNA hybrid or cleaves the phosphodiester bond 5′ of a single ribonucleotide embedded within a DNA duplex, and represents the major RNase H activity at sites of genome replication and repair 44–45. Studies in RNase H2-deficent yeast and mice have established a pivotal role of RNase H2 for genome integrity. RNase H2 mediates the removal of ribonucleotides misincorporated during genome replication by replicative DNA polymerases 46–49. Moreover, ribonucleotides were shown to represent the most common endogenous nucleotide base lesion in replicating cells occurring at a rate of one ribonucleotide per 7000 bases of DNA 47. Single- or double-strand DNA breaks at sites of ribonucleotides resulting from spontaneous hydrolysis or by topoisomerase-I-mediated cleavage induces a DNA damage response to activate DNA repair 50. Indeed, complete RNase H2 deficiency in mice is embryonally lethal due to a massive p53-dependent DNA damage response 47–48. Interestingly, unlike AGS patients, RNase H2-deficient mice do not develop type I IFN activation 47–48. This suggests that RNase H2 mutations in patients with AGS are hypomorphic, and that type I IFN activation may result from a low-level DNA damage response.

SAMHD1 functions as a deoxyguanosine-triphosphate (dGTP)-dependent phosphohydrolase which converts deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), the building blocks of DNA replication, to the constituent deoxynucleoside and inorganic triphosphate, thereby regulating the intracellular dNTP pool 51. SAMHD1 deficiency could therefore promote inappropriately increased DNA synthesis. SAMHD1 restricts infection of myeloid cells with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) 52–53 by depleting the dNTP pool required for reverse transcription of the viral RNA genome in a cyclin A-dependent manner 54,55. This is in contrast to TREX1, which facilitates HIV-1 infection by degrading non-productive reverse transcripts of the viral RNA genome, thereby preventing an anti-viral response 57. Interestingly, interaction with as yet unknown endogenous nucleic acids was shown to be an integral function of SAMHD1, as AGS-associated SAMHD1 mutations have lost this property 58,59. In addition, SAMHD1 was also shown to possess exonuclease activity 60. The physiological functions of SAMHD1 in the absence of retroviral infection are unknown. However, given that SAMHD1 is regulated by cyclin A/CDK1-dependent phosphorylation 55–56, and that imbalances in the intracellular dNTP pools can cause genome instability 61, SAMHD1 may also be involved in the maintenance of genome integrity.

Adenosine deaminase acting on RNA 1 (ADAR1) is an RNA-editing enzyme, which catalyzes the deamination of adenosine to inosine in dsRNA 62. Studies in ADAR1-deficient mice have shown that editing of dsRNAs by ADAR1 is required for the self-renewal capacity of haematopoietic stem cells by suppressing apoptotic type I IFN signalling 63. It is hypothesized that ADAR1 alters the immunoreactive properties of dsRNA molecules derived from retro-elements or inhibits microRNAs involved in the regulation of the IFN signalling pathway 64. In addition, ADAR1 has been implicated both in the promotion and restriction of viral infection 65.

Despite the diversity of the nucleic acid metabolizing pathways, in which TREX1, RNase H2, SAMHD1 and ADAR1 participate, the lack of function of all AGS-associated enzymes appears to result in the intracellular accumulation of nucleic acid species that are recognized as danger signals by sensors of the innate immune system, which then trigger the pathogenic type I IFN response.

Nucleic acid degradation as negative regulator of the innate immune response

SLE is characterized by a chronic overproduction of type I IFN, indicating that an inappropriate activation of anti-viral immunity is key to SLE pathogenesis 66–67. Type I IFNs (IFN-α, IFN-β) have pronounced immune-stimulatory effects that promote the loss of B cell and T cell tolerance, dendritic cell activation and autoantibody production 68. The targets of these autoantibodies are ubiquitous self-antigens, including nucleic acids. These anti-nuclear antibodies form complexes with nuclear antigens released from dying cells 69–70. Immune complex deposition in the capillary bed followed by local complement and leucocyte activation results in destructive tissue inflammation. In addition, these immune complexes represent an important stimulus for more type I IFN production by dendritic cells, further fuelling the autoimmune response 71.

Studies in patients and mouse models suggest that this pathogenetic chain can be initiated by a broad spectrum of different mechanisms. These include defects of B and T cell tolerance due to impaired apoptosis, or uncontrolled T cell co-stimulation resulting from inappropriate expression of co-stimulatory receptors 68. Furthermore, defects in mechanisms responsible for the removal of apoptotic cells and cellular debris were shown to cause lupus or lupus-like disease in humans and mice including, for example, deficiency in complement components C1q, C3 and C4 72.

Compelling evidence suggests that it is the nucleic acid component of the accumulating apoptotic cells which causes disease by triggering pathogen sensors of the innate immune system 71. Virus infection is detected primarily by the recognition of viral nucleic acids. This is accomplished by germline-encoded receptors belonging to the class of pattern recognition receptors, which initiate innate inflammatory responses upon the sensing of danger-associated molecular patterns. Double-stranded and ssRNA as well as ssDNA derived from endocytosed material are sensed in the endosome by TLRs (TLR-3, -7, -8 and -9) 71. In the cytosol or nucleus, known sensors for dsRNA include the retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG)-like helicase receptors RIG-I, melanoma differentiation-associated 5 (MDA5) and the aspartate–glutamate–any amino acid–aspartate/histidine box-containing helicases, DHX36 and DHX9 73. The pyrin and HIN domain-containing protein family (PYHIN) proteins AIM2 and IFI16 as well as DDX41 and cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate (GMP–AMP) synthase are cytosolic receptors for dsDNA 73–74. Many of these nucleic acid sensors trigger an anti-viral type I IFN response. In this context, it is of critical importance that mammalian nucleic acid sensors are characterized by limited capacity to discriminate between self and non-self (i.e. microbial) DNA or RNA. Consequently, an IFN response can, in principle, also be initiated by endogenous nucleic acids. This implies that the organism must be equipped with efficient means to avoid inappropriate recognition of endogenous nucleic acids in order to prevent activation of immune responses leading to autoimmunity.

Nucleolytic degradation of endogenous nucleic acids plays an important role in protection from inappropriate and pathogenic activation of innate sensors 75. Lack of DNase I, the major dsDNA-degrading enzyme in serum, in humans and gene-targeted mice, promotes lupus-like disease 76–77. Mice deficient for DNase II, an enzyme essential for endolysosomal degradation of DNA in macrophages, develop massive IFN-dependent autoimmunity 78. Mutations in the intracellular DNase I-like 3 were also shown to cause a dominant form of lupus erythematosus 79. The association of the AGS-associated genes TREX1, RNase H2, SAMHD1 and ADAR1 with systemic autoimmunity illustrates the importance of co-ordinated pathways orchestrating the degradation of endogenous nucleic acids that are produced continuously during normal cell metabolism, in order to avoid detrimental activation of the innate immune system. While the pathways implicated in AGS pathogenesis, such as apoptotic DNA damage, DNA replication/repair and endogenous retro-elements, have revealed novel cell-intrinsic mechanisms for the initiation of autoimmunity, one important unresolved issue is the exact origin and molecular properties of the accumulating nucleic acid species in patients with AGS. Another important question relates to the nature of innate pattern recognition receptors that mediate the induction of type I IFN. Do cells deficient in RNase H2 or SAMHD1 also activate the STING/TBK1/IRF3 pathway as do TREX1-deficent cells? 80. Interestingly, TREX1-deficient mouse and human fibroblasts were also shown to activate anti-viral genes in an IFN regulatory factor-3 (IRF3)-mediated, type I IFN-independent manner, which is accompanied by expansion of the lysosomal compartment 80, raising the question as to whether an increased lysosomal activity could contribute to autoimmunity. Finally, it will be important to understand which cells initiate and sustain the pathogenic type I IFN response. Elucidation of the responsible sensors and their signalling pathways may lead to the identification of new target molecules for therapeutic intervention.

Implications for targeted therapeutic intervention

At present, no effective cure for SLE is known and current approaches rely primarily upon unspecific immunosuppression with corticosteroids and cytostatic drugs or the anti-malarial hydroxychloroquine, with considerable side effects 1. The search for novel more effective, more specific and less toxic drugs is complicated by the clinical heterogeneity of the patient population, which poses a major challenge regarding not only the assessment of disease activity but also for the establishment of reliable clinical outcome measures that can be applied to the evaluation of drug responses 81. The lack of suitable biomarkers has further impeded efforts to evaluate new SLE therapeutics in clinical trials, underpinning the need for more specific tools for diagnosis, disease classification and assessment of disease activity.

During recent years, a number of promising biologicals have been developed that target specific lymphocyte populations [cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4), CD20, CD22, B lymphocyte stimulator/B cell activating factor (BLyS/BAFF), inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, IFN-α, IFN-γ] or other molecules and their testing in SLE has raised hopes considerably, with several being currently under investigation in Phase II or Phase III clinical trials 82–83. The B cell inhibiting monoclonal antibody against BlyS/BAFF, belimumab, the first biological approved for SLE, has shown modest success in a subgroup of serologically active SLE patients 84. This observation exemplifies that due to the multi-factorial pathogenesis of SLE a new drug may have beneficial effects in perhaps only a subset of patients. The extraordinary genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of SLE requires knowledge of the full spectrum of disease mechanisms in order to provide individually tailored therapeutic intervention. The elucidation of TREX1-associated forms of lupus has set the stage towards a classification of disease subentities based on pathogenic criteria and is expected to have an impact upon clinical decision-making. Thus, it is conceivable that SLE patients with the TREX1 mutation may benefit particularly from type I IFN blockade. Conversely, given the link of TREX1 and RNase H2 to increased DNA damage 34,47, a more cautious use of genotoxic drugs such as azathioprine or methotrexate might be advisable. It will also be of interest to determine whether or not patients with TREX1-associated AGS or lupus, like TREX1-deficient mice, suffer from uncontrolled activation of endogenous retro-elements 35 and, if so, if they respond to anti-retroviral therapy 43.

Conclusion

The discovery of the genetic causes of AGS and familial chilblain lupus has established a novel role of the intracellular nucleic acid metabolism in the control of the innate immune response and has provided novel insight into mechanisms of immune tolerance. As there are more AGS genes to be discovered, future work is expected to broaden our understanding further of how the organism can protect itself against inappropriate immune activation caused by self nucleic acids, while sustaining a prompt and efficient immune defence against foreign nucleic acids derived from invading pathogens. This may not only be of relevance to other autoimmune conditions characterized by a deregulated type I-IFN response, such as Sjögren's syndrome, dermatomyositis and systemic sclerosis 85–86, but may also reveal novel pathways that could potentially be targeted for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

We thank Axel Roers for insightful discussions. This study was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KFO 249/LE1074/4-1 to M. L.-K and KFO249/GU1212/1-1 to C. G.) and the Friede Springer Stiftung.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rahman A, Isenberg DA. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:929–939. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–1277. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Roseman JM, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XIX. Natural history of the accrual of the American College of Rheumatology criteria prior to the occurrence of criteria diagnosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:609–615. doi: 10.1002/art.20548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus. 2006;15:308–318. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2305xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamphuis S, Silverman ED. Prevalence and burden of pediatric-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:538–546. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhodes B, Vyse TJ. General aspects of the genetics of SLE. Autoimmunity. 2007;40:550–559. doi: 10.1080/08916930701510657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bijl M, Kallenberg CG. Ultraviolet light and cutaneous lupus. Lupus. 2006;15:724–727. doi: 10.1177/0961203306071705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harley JB, Harley IT, Guthridge JM, James JA. The curiously suspicious: a role for Epstein–Barr virus in lupus. Lupus. 2006;15:768–777. doi: 10.1177/0961203306070009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morel L. Genetics of SLE: evidence from mouse models. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:348–357. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harley IT, Kaufman KM, Langefeld CD, Harley JB, Kelly JA. Genetic susceptibility to SLE: new insights from fine mapping and genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:285–290. doi: 10.1038/nrg2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manjarrez-Orduno N, Marasco E, Chung SA, et al. CSK regulatory polymorphism is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus and influences B-cell signaling and activation. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1227–1230. doi: 10.1038/ng.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michels AW, Gottlieb PA. Autoimmune polyglandular syndromes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:270–277. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aicardi J, Goutieres F. A progressive familial encephalopathy in infancy with calcifications of the basal ganglia and chronic cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:49–54. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lebon P, Badoual J, Ponsot G, Goutieres F, Hemeury-Cukier F, Aicardi J. Intrathecal synthesis of interferon-alpha in infants with progressive familial encephalopathy. J Neurol Sci. 1988;84:201–208. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(88)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolmie JL, Shillito P, Hughes-Benzie R, Stephenson JB. The Aicardi–Goutieres syndrome (familial, early onset encephalopathy with calcifications of the basal ganglia and chronic cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis) J Med Genet. 1995;32:881–884. doi: 10.1136/jmg.32.11.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramantani G, Kohlhase J, Hertzberg C, et al. Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of lupus erythematosus in Aicardi–Goutieres syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1469–1477. doi: 10.1002/art.27367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crow YJ, Hayward BE, Parmar R, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the 3′–5′ DNA exonuclease TREX1 cause Aicardi–Goutières syndrome at the AGS1 locus. Nat Genet. 2006;38:917–920. doi: 10.1038/ng1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crow YJ, Leitch A, Hayward BE, et al. Mutations in genes encoding ribonuclease H2 subunits cause Aicardi–Goutières syndrome and mimic congenital viral brain infection. Nat Genet. 2006;38:910–916. doi: 10.1038/ng1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rice GI, Bond J, Asipu A, et al. Mutations involved in Aicardi–Goutières syndrome implicate SAMHD1 as regulator of the innate immune response. Nat Genet. 2009;41:829–832. doi: 10.1038/ng.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice GI, Kasher PR, Forte GM, et al. Mutations in ADAR1 cause Aicardi–Goutières syndrome associated with a type I interferon signature. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1243–1248. doi: 10.1038/ng.2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee-Kirsch MA, Gong M, Schulz H, et al. Familial chilblain lupus, a monogenic form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, maps to chromosome 3p. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:731–737. doi: 10.1086/507848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rice G, Newman WG, Dean J, et al. Heterozygous mutations in TREX1 cause familial chilblain lupus and dominant Aicardi–Goutieres syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:811–815. doi: 10.1086/513443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee-Kirsch MA, Chowdhury D, Harvey S, et al. A mutation in TREX1 that impairs susceptibility to granzyme A-mediated cell death underlies familial chilblain lupus. J Mol Med. 2007;85:531–537. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richards A, van den Maagdenberg AM, Jen JC, et al. C-terminal truncations in human 3′–5′ DNA exonuclease TREX1 cause autosomal dominant retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1068–1070. doi: 10.1038/ng2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haaxma CA, Crow YJ, van Steensel MA, et al. A de novo p.Asp18Asn mutation in TREX1 in a patient with Aicardi–Goutières syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2612–2617. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tungler V, Silver RM, Walkenhorst H, Gunther C, Lee-Kirsch MA. Inherited or de novo mutation affecting aspartate 18 of TREX1 results in either familial chilblain lupus or Aicardi–Goutières syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:212–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravenscroft JC, Suri M, Rice GI, Szynkiewicz M, Crow YJ. Autosomal dominant inheritance of a heterozygous mutation in SAMHD1 causing familial chilblain lupus. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:235–237. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee-Kirsch MA, Gong M, Chowdhury D, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the 3′–5′ DNA exonuclease TREX1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1065–1067. doi: 10.1038/ng2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Vries B, Steup-Beekman GM, Haan J, et al. TREX1 gene variant in neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1886–1887. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.114157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Namjou B, Kothari PH, Kelly JA, et al. Evaluation of the TREX1 gene in a large multi-ancestral lupus cohort. Genes Immun. 2011;12:270–279. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazur DJ, Perrino FW. Identification and expression of the TREX1 and TREX2 cDNA sequences encoding mammalian 3′–>5′ exonucleases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19655–19660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chowdhury D, Beresford PJ, Zhu P, et al. The exonuclease TREX1 is in the SET complex and acts in concert with NM23-H1 to degrade DNA during granzyme A-mediated cell death. Mol Cell. 2006;23:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang YG, Lindahl T, Barnes DE. Trex1 exonuclease degrades ssDNA to prevent chronic checkpoint activation and autoimmune disease. Cell. 2007;131:873–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stetson DB, Ko JS, Heidmann T, Medzhitov R. Trex1 prevents cell-intrinsic initiation of autoimmunity. Cell. 2008;134:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deininger PL, Moran JV, Batzer MA, Kazazian HH., Jr Mobile elements and mammalian genome evolution. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:651–658. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hancks DC, Kazazian HH., Jr Active human retrotransposons: variation and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dewannieux M, Dupressoir A, Harper F, Pierron G, Heidmann T. Identification of autonomous IAP LTR retrotransposons mobile in mammalian cells. Nat Genet. 2004;36:534–539. doi: 10.1038/ng1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young GR, Eksmond U, Salcedo R, Alexopoulou L, Stoye JP, Kassiotis G. Resurrection of endogenous retroviruses in antibody-deficient mice. Nature. 2012;491:774–778. doi: 10.1038/nature11599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu P, Lubben W, Slomka H, et al. Nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors are essential for the control of endogenous retrovirus viremia and ERV-induced tumors. Immunity. 2012;37:867–879. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morita M, Stamp G, Robins P, et al. Gene-targeted mice lacking the Trex1 (DNase III) 3′–>5′ DNA exonuclease develop inflammatory myocarditis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6719–6727. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6719-6727.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gall A, Treuting P, Elkon KB, et al. Autoimmunity initiates in nonhematopoietic cells and progresses via lymphocytes in an interferon-dependent autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2012;36:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck-Engeser GB, Eilat D, Wabl M. An autoimmune disease prevented by anti-retroviral drugs. Retrovirology. 2011;8:91. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chon H, Vassilev A, DePamphilis ML, et al. Contributions of the two accessory subunits, RNASEH2B and RNASEH2C, to the activity and properties of the human RNase H2 complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:96–110. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bubeck D, Reijns MA, Graham SC, Astell KR, Jones EY, Jackson AP. PCNA directs type 2 RNase H activity on DNA replication and repair substrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3652–3666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nick McElhinny SA, Kumar D, Clark AB, et al. Genome instability due to ribonucleotide incorporation into DNA. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:774–781. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reijns MA, Rabe B, Rigby RE, et al. Enzymatic removal of ribonucleotides from DNA is essential for mammalian genome integrity and development. Cell. 2012;149:1008–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hiller B, Achleitner M, Glage S, Naumann R, Behrendt R, Roers A. Mammalian RNase H2 removes ribonucleotides from DNA to maintain genome integrity. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1419–1426. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sparks JL, Chon H, Cerritelli SM, et al. RNase H2-initiated ribonucleotide excision repair. Mol Cell. 2012;47:980–986. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim N, Huang SN, Williams JS, et al. Mutagenic processing of ribonucleotides in DNA by yeast topoisomerase I. Science. 2011;332:1561–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.1205016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldstone DC, Ennis-Adeniran V, Hedden JJ, et al. HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature. 2011;480:379–382. doi: 10.1038/nature10623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, et al. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature. 2011;474:658–661. doi: 10.1038/nature10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, et al. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature. 2011;474:654–657. doi: 10.1038/nature10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lahouassa H, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, et al. SAMHD1 restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by depleting the intracellular pool of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:223–228. doi: 10.1038/ni.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cribier A, Descours B, Valadao AL, Laguette N, Benkirane M. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by cyclin A2/CDK1 regulates its restriction activity toward HIV-1. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1036–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White TE, Brandariz-Nunez A, Valle-Casuso JC, et al. The retroviral restriction ability of SAMHD1, but not its deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase activity, is regulated by phosphorylation. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yan N, Regalado-Magdos AD, Stiggelbout B, Lee-Kirsch MA, Lieberman J. The cytosolic exonuclease TREX1 inhibits the innate immune response to human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1005–1013. doi: 10.1038/ni.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goncalves A, Karayel E, Rice GI, et al. SAMHD1 is a nucleic-acid binding protein that is mislocalized due to Aicardi–Goutières syndrome-associated mutations. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1116–1122. doi: 10.1002/humu.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tungler V, Staroske W, Kind B, et al. Single-stranded nucleic acids promote SAMHD1 complex formation. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013;91:759–770. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-0995-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beloglazova N, Flick R, Tchigvintsev A, et al. Nuclease activity of the human SAMHD1 protein implicated in the Aicardi–Goutières syndrome and HIV-1 restriction. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:8101–8110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.431148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang X, Mathews CK. Natural DNA precursor pool asymmetry and base sequence context as determinants of replication fidelity. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8401–8404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Q. RNA editing catalyzed by ADAR1 and its function in mammalian cells. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2011;76:900–911. doi: 10.1134/S0006297911080050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Q, Khillan J, Gadue P, Nishikura K. Requirement of the RNA editing deaminase ADAR1 gene for embryonic erythropoiesis. Science. 2000;290:1765–1768. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iizasa H, Nishikura K. A new function for the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:16–18. doi: 10.1038/ni0109-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Samuel CE. Adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs) are both antiviral and proviral. Virology. 2011;411:180–193. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, et al. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2610–2615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ronnblom L, Alm GV, Eloranta ML. Type I interferon and lupus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:471–477. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832e089e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shlomchik MJ, Craft JE, Mamula MJ. From T to B and back again: positive feedback in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:147–153. doi: 10.1038/35100573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leadbetter EA, Rifkin IR, Hohlbaum AM, Beaudette BC, Shlomchik MJ, Marshak-Rothstein A. Chromatin–IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2002;416:603–607. doi: 10.1038/416603a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lovgren T, Eloranta ML, Bave U, Alm GV, Ronnblom L. Induction of interferon-alpha production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells by immune complexes containing nucleic acid released by necrotic or late apoptotic cells and lupus IgG. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1861–1872. doi: 10.1002/art.20254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marshak-Rothstein A. Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:823–835. doi: 10.1038/nri1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cook HT, Botto M. Mechanisms of Disease: the complement system and the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:330–337. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Atianand MK, Fitzgerald KA. Molecular basis of DNA recognition in the immune system. J Immunol. 2013;190:1911–1918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339:786–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1232458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hornung V, Latz E. Intracellular DNA recognition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:123–130. doi: 10.1038/nri2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Napirei M, Karsunky H, Zevnik B, Stephan H, Mannherz HG, Moroy T. Features of systemic lupus erythematosus in Dnase1-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25:177–181. doi: 10.1038/76032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yasutomo K, Horiuchi T, Kagami S, et al. Mutation of DNASE1 in people with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2001;28:313–314. doi: 10.1038/91070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nagata S. Autoimmune diseases caused by defects in clearing dead cells and nuclei expelled from erythroid precursors. Immunol Rev. 2007;220:237–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Al-Mayouf SM, Sunker A, Abdwani R, et al. Loss-of-function variant in DNASE1L3 causes a familial form of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1186–1188. doi: 10.1038/ng.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hasan M, Koch J, Rakheja D, et al. Trex1 regulates lysosomal biogenesis and interferon-independent activation of antiviral genes. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:61–71. doi: 10.1038/ni.2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eisenberg R. Why can't we find a new treatment for SLE? J Autoimmun. 2009;32:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wallace DJ. Advances in drug therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus. BMC Med. 2010;8:77. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chan AC, Carter PJ. Therapeutic antibodies for autoimmunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:301–316. doi: 10.1038/nri2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Horowitz DL, Furie R. Belimumab is approved by the FDA: what more do we need to know to optimize decision making? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14:318–323. doi: 10.1007/s11926-012-0256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mavragani CP, Crow MK. Activation of the type I interferon pathway in primary Sjogren's syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2010;35:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eloranta ML, Franck-Larsson K, Lovgren T, et al. Type I interferon system activation and association with disease manifestations in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1396–1402. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.121400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]