Abstract

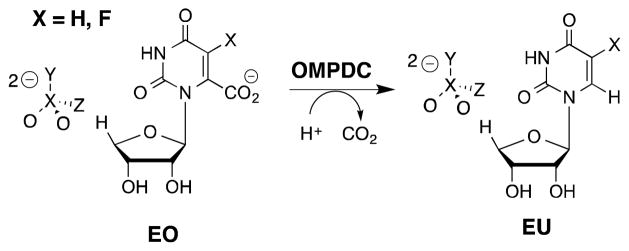

Orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase catalyzes the decarboxylation of truncated substrate (1-β-D-erythrofuranosyl)orotic acid (EO) to form (1-β-D-erythrofuranosyl)uracil (EU). This enzymecatalyzed reaction is activated by tetrahedral oxydianions, which bind weakly to unliganded OMPDC and tightly to the enzyme-transition state complex, with the following intrinsic oxydianion binding energies (kcal/mole): SO32−, −8.3; HPO32−, −7.7; S2O32−, −4.6; SO42−, −4.5; HOPO32−, −3.0; HOAsO32−, no activation detected. We propose that oxydianion and orotate binding domains perform complementary functions in catalysis of decarboxylation reactions. (1) The orotate binding domain carries out decarboxylation of the orotate ring. (2) The activating oxydianion binding domain has the cryptic function of utilizing binding interactions with tetrahedral inorganic oxydianions to drive an enzyme conformational change that results in the stabilization of transition states at the distant orotate domain.

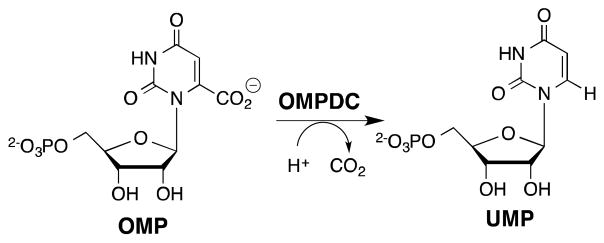

Orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase (OMPDC) catalyzes the chemically difficult decarboxylation of OMP to form uridine 5′-monophosphate (Scheme 1).1,2 OMPDC provides a startling 31 kcal/mol stabilization of the vinyl carbanion-like transition state for the decarboxylation reaction.3 By contrast, the observed OMP binding energy is 8 kcal/mol,4 so that the large intrinsic ligand binding energy is only expressed after formation of the Michaelis complex to OMP.5,6

Scheme 1.

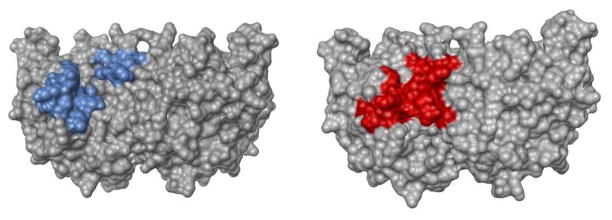

Interactions between the phosphodianion gripper loop (Pro202 – Val220) of OMPDC from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ScOMPDC) and the phosphodianion of OMP (Figure 1)7 result in an 11 kcal/mol stabilization of the transition state for ScOMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of the truncated substrate (1-β-D-erythrofuranosyl)orotic acid (EO) to form (1-β-D-erythrofuranosyl)uracil (EU),8,9 and a 9 kcal/mol stabilization of the transition state for the catalyzed deuterium exchange reaction of (1-β-D-erythrofuranosyl)-5-fluorouracil (FEU).10–12 Phosphite dianion activates OMPDC for catalysis of the decarboxylation and deuterium exchange reactions of these truncated substrates.8,10 We now report that a series of structurally homologous tetrahedral oxydianions, which includes phosphite dianion, activate OMPDC for catalysis of decarboxylation of EO.

Figure 1.

Space-filling models that show open unliganded ScOMPDC on the left (PDB entry 1DQW), and the complex to 6-hydroxyuridine 5′-phosphate (PDB entry 1DQX) on the right. The colored phosphodianion gripper loop on the left-hand side (Pro202 – Val220), and the pyrimidine umbrella (Glu151 - Thr165) on the right hand side of each structure “trap” the ligand at the enzyme active site.

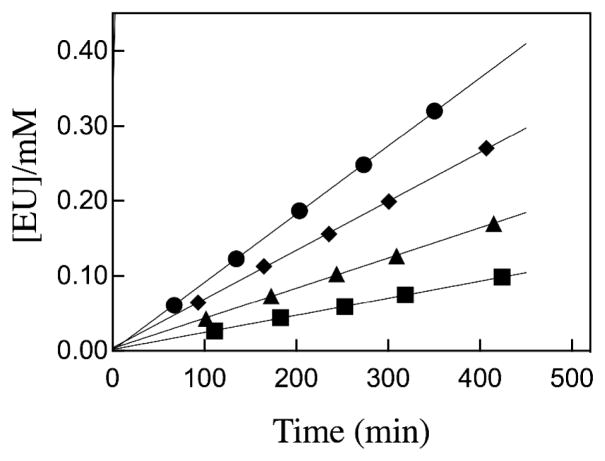

The decarboxylation of EO catalyzed by ScOMPDC in the presence of tetrahedral inorganic oxydianions (Scheme 2) was monitored by HPLC as described in earlier work.8,13 Figure 2 shows the linear time course that defines the initial velocity (vi) for the formation of EU from the reaction of 5.2 mM EO (≪ Kd) catalyzed by 5.4 μM ScOMPDC, in the presence of various concentrations of thiosulfate dianion (S2O32−, Chart 1) and 10 mM MOPS at pH 7.1 and I = 0.14 (NaCl). The values of vi and the concentration of enzyme and substrate were substituted into eq 1 to give second-order rate constants (kcat/Km)obs (M−1 s−1) for the decarboxylation of EO by ScOMPDC that are reported in Table S1 of the Supporting Information. Table S1 also reports the values of (kcat/Km)obs for the ScOMPDC-catalyzed reactions of EO activated by SO42− and HOPO32− at pH 7.1, 25 °C and I = 0.14 (NaCl) determined by the same procedure. There is no detectable activation of the ScOMPDC-catalyzed reactions of EO by 33 mM arsenate dianion or 115 mM nitrate anion (Table S1).

Scheme 2.

Figure 2.

Time courses for ScOMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation of EO at pH 7.1, 25 °C and I = 0.14 (NaCl) in the presence of thiosulfate dianion (S2O32−): (■), 2.7 mM; (▲), 5.4 mM: (◆), 10.8 mM; (●), 20.3 mM thiosulfate dianion.

Chart 1.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The complete time course for the reaction of 0.1 mM EO (≪ Km) to give EU catalyzed by ScOMPDC in the presence of phosphite (pH 7.0)8 and sulfite dianion (pH 7.1), buffered by 5 mM MOPS at 25 °C and I = 0.14 (NaCl), was monitored spectrophotometrically at 283 nm.8,9 The reaction in the presence of phosphite dianion exhibited good first order kinetics for > 10 halftimes,8 but there was a slow downward drift in absorbance for the reaction in the presence of sulfite dianion at > 5 reaction halftimes. Control experiments showed that this decrease in absorbance results from reaction of product EU with sulfite dianion. The values of kobs were determined from the fit of the absorbance data over the first 5 (SO32−) or 10 (HPO32−) reaction halftimes to a standard single exponential rate equation. These were used to calculate the values of (kcat/Km)obs = kobs/[OMPDC] reported in Table S1.

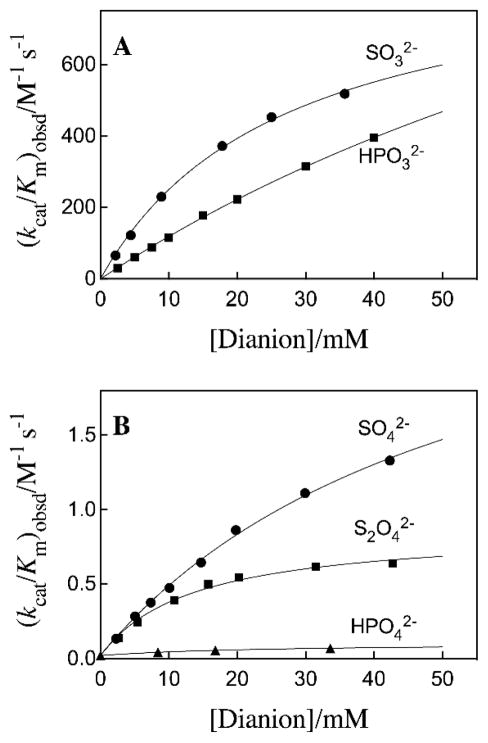

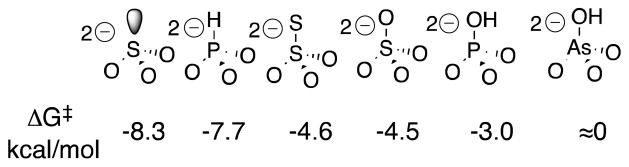

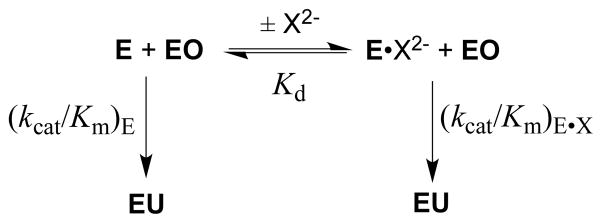

Figures 3A and 3B show the dependence of (kcat/Km)obs for OMPDC-catalyzed reactions of EO on the concentration of several oxydianion activators. The solid lines describe the nonlinear least squares fit of these data to eq 2 derived for Scheme 3, using the previously determined value of (kcat/Km)E = 0.026 M−1 s−1 14 and the appropriate values of Kd and (kcat/Km)E•X from Table 1. The kinetic parameters (kcat/Km)E, (kcat/Km)E•X and Kd, for oxydianion activation define three sides of the thermodynamic cycle shown in Scheme 4. Combining the values of (kcat/Km)E•X and Kd from Table 1 with (kcat/Km)E = 0.026 M−1 s−1 (eq 3) for the unactivated decarboxylation reaction gives the values of Kd‡ for disassociation of oxydianions from the transition state complex (Table 1).14 The binding energies ΔG‡ for formation of different complexes [E•X2−•EO]‡, calculated from Kd‡, are reported in Table 1 and Chart 1. We conclude that these dianions are powerful activators of OMPDC-catalyzed decarboxylation, and that this activity for activation has been recruited for OMP by tethering the phosphodianion to the nucleoside orotidine.

Figure 3.

Dependence of second-order rate constants (kcat/Km)obs for OMPDC-catalyzed turnover of EO on the concentration of oxydianion activators.

Scheme 3.

Table 1.

Kinetic Parameters for Activation of OMPDC by Oxydianions and Derived Parameters for Dianion Binding to OMPDC and to [E•EO]‡ (Scheme 4).a

| Oxydianion | Kd/Mb | (kcat/Km)E•X M−1 s−1 b | Kd‡/M c | RTln(Kd‡) kcal/mol d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPO32− e | 0.14 | 1600 | 2.3 × 10−6 | −7.7 |

| HOPO32− | 0.025 | 0.11 | 5.9 × 10−3 | −3.0 |

| SO32− | 0.027 | 920 | 7.6 × 10−7 | −8.3 |

| SO42− | 0.055 | 3.1 | 4.6 × 10−4 | −4.5 |

| S2O32− | 0.014 | 0.87 | 4.2 × 10−4 | −4.6 |

| HOAsO32− | No detectable activation | |||

For reactions at pH 7.1, 25 °C and I = 0.14 (NaCl) unless noted otherwise.

Experimental kinetic parameter defined by Scheme 3.

Disassociation constant for release of the oxydianion from the transition state complex, calculation using eq 3 derived for Scheme 4.

The intrinsic dianion binding energy.

Ref 8.

Scheme 4.

Free OMPDC shows a weak affinity for tetrahedral oxydianions (Kd ≥ 0.027 M), and the [E•EO] ‡ complex (Scheme 4) shows a high affinity for binding oxydianions. This complex has the largest affinity (8 kcal/mol) for isoelectronic HPO32− and SO32−. The increase in dianion size, and reduction in charge density, at the individual oxygen of SO42− compared with SO32− result in a decrease in the intrinsic dianion binding energy from −8.3 to −4.5 kcal/mol. The similar −4.5 and −4.6 kcal/mol intrinsic binding energy for SO42− and S2O32−, respectively, may reflect the offsetting effects of the larger size of the -S− at S2O32− compared with –O− at SO42−, and the greater charge at the electronegative oxygen atoms of S2O32− that interact with protein side chains. The small −3.0 kcal/mol intrinsic dianion binding energy for HOPO32−, and the > 8 kcal/mol difference between the dianion binding energy for HPO32− and HOAsO32− are consistent with demanding steric/polar requirements to obtain the precise fit at the dianion binding site required for optimal enzyme activation. The reproduction of these intrinsic dianion binding energies provides a stringent test for computational methods developed to model catalysis by OMPDC.15–17

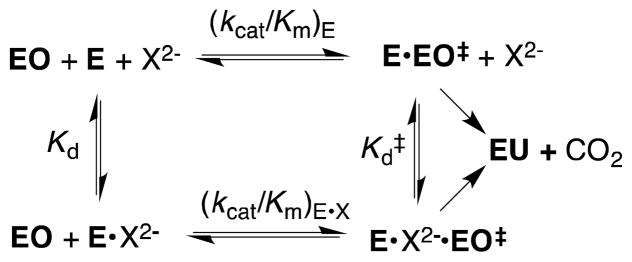

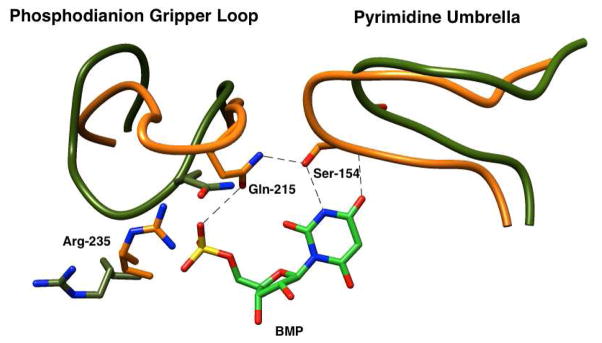

The X-ray crystal structure of the complex between yeast OMPDC and the intermediate analog 6-hydroxyuridine 5′-phosphate (BMP, Figure 4) reveals interactions between the ligand phosphodianion and the polar side chains of Gln215 and Tyr217 (not drawn in Figure 4) in the phosphodianion gripper loop (Pro202 – Val220) and with Arg235. The orotate ring interacts with residues from a hydrophobic umbrella (Ala151 – Thr165). The gripper loop is well separated from site of decarboxylation. For example, the distance between the guanidinium nitrogen and the C-6 oxygen of BMP is ca. 10 Å. The Q215A, Y217A and R235A mutations at OMPDC have little (≤ 2.4-fold) effect on kcat/Km for decarboxylation of the phosphodianion truncated substrate EO, so that there are no more than weak interactions between these side chains and the transition state for decarboxylation at the distant pyrimidine ring.14 By contrast, the Q215A, Y217A and R235A mutations result in up to 104-fold decreases in kcat/Km for catalysis of decarboxylation of OMP and in (kcat/Km)E•X/Kd (Scheme 4) for dianion activation of the catalyzed decarboxylation reaction of EO, so that these enzyme-dianion interactions are utilized in the stabilization of transition states that form at the distant catalytic site.14,18

Figure 4.

X-ray crystal structure (PDB entry 1DQX) of yeast OMPDC in a complex with 6-hydroxyuridine 5′-phosphate that shows interactions of the phosphodianion with the side chains from a loop that runs from Pro202 to Val220 and of the pyrimidine ring with a hydrophobic umbrella that runs from Ala151 – Thr165. The connecting hydrogen bond is between the side chains of Gln215 and Ser154. Reprinted with permission from Ref 18. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

The strong dependence of the magnitude of enzyme activation on the oxydianion structure (Table 1) demands a precisely structured enzyme active site in order to obtain the extraordinary rate acceleration observed for OMPDC. The results may be rationalized by a model where the unactivated ((kcat/Km)E, Scheme 4) and dianion activated ((kcat/Km)E•X) decarboxylation reactions proceed through a single high-energy, catalytically active, loop-closed form of OMPDC that is stabilized by hydrogen bonding and ion-pairing interactions between dianions and the gripper loop.6,19–21 We cannot rigorously exclude the possibility that the two decarboxylation reactions are catalyzed by different conformations of OMPDC. However, the reactive enzyme conformation must form at some low concentration in the absence of added dianions, so that the utilization of a single protein conformation to catalyze both reactions provides for the greatest economy in reaction pathways. An important element of the enzyme conformational change is formation of a hydrogen bond between the side chains of Ser154 and Gln215 (Figure 4).13 This couples closure of the gripper loop, which alone is not expected to strongly activate OMPDC for decarboxylation at the distant catalytic site, and closure of the pyrimidine umbrella, which we propose strongly activates OMPDC for catalysis of decarboxylation of OMP or EO.18

Wolfenden proposed that optimal enzymatic catalysis of many reactions is best obtained at an active site where the substrate is trapped in a protein cage (Figure 1) and completely surrounded by functional groups of the enzyme. 22 We propose for OMPDC that the exclusive catalytic role of protein-dianion interactions is the stabilization of this active closed protein cage (Figure 1), and that transfer of OMP from water to the protein cage is energetically uphill for the reaction of EO and assisted by interactions between OMPDC and the phosphodianion of OMP. The precise conformational changes associated with formation of caged enzyme-substrate complexes are expected to differ for enzymes that utilize the intrinsic dianion binding energy to stabilize the transition states for decarboxylation (OMPDC),8 proton transfer (triosephosphate isomerase (TIM)),23 hydride transfer (glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase),24 phosphoryl transfer (phosphoglucomutate),25 reductoisomerization (1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase)26 and, almost certainly, other enzymatic reactions. However, these mechanistic issues have not been probed in detail, except for recent mutagenesis studies on the isomerization reaction catalyzed by TIM.27–30

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Kinetic parameters for turnover of EO by OMPDC in the presence of oxydianions at pH 7.1 and I = 0.14 maintained with NaCl. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant GM39754 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Miller BG. Top Curr Chem. 2004;238:43–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller BG, Wolfenden R. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:847–885. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radzicka A, Wolfenden R. Science. 1995;267:90–93. doi: 10.1126/science.7809611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter DJT, Short SA. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11788–11800. doi: 10.1021/bi001199v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jencks WP. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1975;43:219–410. doi: 10.1002/9780470122884.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2021–2035. doi: 10.1021/bi301491r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller BG, Hassell AM, Wolfenden R, Milburn MV, Short SA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2011–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030409797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amyes TL, Richard JP, Tait JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15708–15709. doi: 10.1021/ja055493s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toth K, Amyes TL, Wood BM, Chan KK, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8006–8013. doi: 10.1021/bi901064k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goryanova B, Amyes TL, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:6545–6548. doi: 10.1021/ja201734z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsang WY, Wood BM, Wong FM, Wu W, Gerlt JA, Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:14580–14594. doi: 10.1021/ja3058474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amyes TL, Wood BM, Chan K, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1574–1575. doi: 10.1021/ja710384t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnett SA, Amyes TL, Wood BM, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7785–7787. doi: 10.1021/bi800939k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amyes TL, Ming SA, Goldman LM, Wood BM, Desai BJ, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2012;51:4630–4632. doi: 10.1021/bi300585e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao J. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:184–192. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warshel A, Florian J, Strajbl M, Villa J. ChemBioChem. 2001;2:109–111. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010202)2:2<109::AID-CBIC109>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vardi-Kilshtain A, Doron D, Major DT. Biochemistry. 2013;52:4382–4390. doi: 10.1021/bi400190v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goryanova B, Goldman LM, Amyes TL, Gerlt JA, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2013;52:7500–7511. doi: 10.1021/bi401117y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2012;51:2652–2661. doi: 10.1021/bi300195b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Go MK, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5769–5778. doi: 10.1021/bi900636c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malabanan MM, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:702–710. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfenden R. Mol and Cell Biochem. 1974;3:207–211. doi: 10.1007/BF01686645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5841–5854. doi: 10.1021/bi700409b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsang WY, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4575–4582. doi: 10.1021/bi8001743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ray WJ, Jr, Long JW, Owens JD. Biochemistry. 1976;15:4006–4017. doi: 10.1021/bi00663a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kholodar SA, Murkin AS. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2302–2308. doi: 10.1021/bi400092n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhai X, Amyes TL, Wierenga RK, Loria JP, Richard JP. Biochemistry. 2013;52:5928–5940. doi: 10.1021/bi401019h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malabanan MM, Nitsch-Velasquez L, Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:5978–5981. doi: 10.1021/ja401504w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malabanan MM, Koudelka AP, Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10286–10298. doi: 10.1021/ja303695u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malabanan MM, Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16428–16431. doi: 10.1021/ja208019p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Kinetic parameters for turnover of EO by OMPDC in the presence of oxydianions at pH 7.1 and I = 0.14 maintained with NaCl. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.