Abstract

Data collectors play a vital role in producing scientific knowledge. They are also an important component in understanding the practice of bioethics. Yet, very little attention has been given to their everyday experiences or the context in which they are expected to undertake these tasks. This paper argues that while there has been extensive philosophical attention given to ‘the what’ and ‘the why’ in bioethics – what action is taken place and why – these should be considered along ‘the who’ – who are the individuals tasked with bioethics and what can their insights bring to macro-level and abstract discussions of bioethics. This paper will draw on the philosophical theories of Paul Ricoeur which compliments a sociological examination of data collectors experiences and use of their agency coupled with a concern for contextual and institutional factors in which they worked.

In emphasising everyday experiences and contexts, I will argue that data collectors' practice of bioethics was shaped by their position at the frontline of face-to-face interactions with medical research participants and community members, alongside their own personal ethical values and motivations. Institutional interpretations of bioethics also imposed certain parameters on their bioethical practice but these were generally peripheral to their sense of obligation and the expectations conferred in witnessing the needs and suffering of those they encountered during their quotidian research duties.

This paper will demonstrate that although the principle of autonomy has dominated discussions of bioethics and gaining informed consent seen as a central facet of ethical research by many research institutions, for data collectors this principle was seldom the most important marker of their ethical practice. Instead, data collectors were concerned with remedying the dilemmas they encountered through enacting their own interpretations of justice and beneficence and imposing their own agency on the circumstances they experienced. Their practice of bioethics demonstrates their contribution to the conduct of research and the shortcomings of an over-emphasis on autonomy.

Keywords: Data collectors, Bioethics, Medical research, Autonomy, Justice

Highlights

-

•

Data collectors play an important role in our understanding of bioethics in practice.

-

•

Data collectors regularly witness to the pain, suffering and demands of others and this shaped their everyday experiences.

-

•

Data collectors generally felt that an emphasis on autonomy by research institutions misunderstood their daily experiences.

-

•

In practice data collectors drew on their interpretations of notions of beneficence and justice in solving their dilemmas.

-

•

Data collectors actions provides insights into what medical research and bioethics come to mean in context where health is a scarce resource.

Introduction

While the job titles given to frontline data collectors may vary (e.g. field assistants, fieldworkers and community interviewers) a defining feature of these roles is not only collecting samples of bodily fluids, undertaking interviews and collecting survey data for medical research but these research employees must also adhere to prescribed bioethical principles. Therefore, a great deal is dependent on data collectors practices and views. At the same time, there are numerous competing interests which they must reconcile in their practice of bioethics. For instance, to remain employed, data collectors must adhere to institutional rules, while being seen to address community expectations and ethical values. This paper will explore this tension in data collectors' everyday research experiences and examine the features which they presented as shaping their bioethical practice. It will draw on ethnographic and interview data and insights gained through graphic elucidation techniques. This paper will demonstrate the value of exploring data collectors' views and the unique insights they bring to our understanding of bioethics in practice.

Foregrounding the background

Academic medical research publications often present the socio-economic, political and geographical context of research as background information. Similarly, bioethical discussions rarely extend to examinations of structural factors and whether these should determine the ethical positions adopted by biomedical institutions. Furthermore, most medical research data collection takes place in areas which are physically and economically distanced from institutional board rooms and headquarters. When taken together, these factors relegate some of the most illuminating features of bioethical practice to the background of bioethical discussions. Yet, focussing on ‘the who’ (Ricoeur, 1992: p. 90) of bioethics, also for scope to consider such features because for data collectors it is precisely such grounded details which operate not in the background but rather at the forefront of their everyday bioethical practice. For this reason, this paper will emphasise what was foremost in data collectors' accounts as influential in their experiences and practice.

Living the statistics

This study of frontline data collectors was conducted in Nyanza Province, western Kenya. This is a popular location for medical research, with long history of investigations on malaria, sleeping sickness and HIV/AIDS (Chaiken, 1998; Sullivan, 1993). This study examined the data collectors employed by medical research projects which were conducted in a location where official statistics suggested that between 53 and 63% of the local population live below the poverty line (UNHABITAT, 2006) with unemployment officially estimated at approximately 30% (Kenya National AIDS Control Council, 2009). The average life expectancy at birth was 37 years for men and 40 years for women. Among children there was an under-five mortality rate of 220 deaths per 1000 live births (UNHABITAT, 2006). Many of these deaths were attributed to malaria and HIV/AIDs. For example, the adult HIV prevalence rate was estimated at 15% (with some districts within this province reporting rates of 26%) (Kenya National AIDS Control Council, 2009). This area also had one of the lowest numbers of hospital beds in Kenya, with only 15.4 beds per 100,000 population (Wamai, 2009). Even when beds were available, they were costly and commuting to hospitals and health facilities on poorly maintained and accident prone roads, created other challenges to their access (Feikin, Nguyen, Adazu, Ombok, & Audi, 2009). These startling statistics are important in this discussion because they form an integral part of defining the ethical predicaments and quotidian experiences of data collectors whose duties meant that they also lived these statistics.

However, such statistics are most often employed to justify public research and interventions, to show the value of research to reduce the burden of diseases, such as malaria and HIV/AIDs. For example, the 10/90 gap refers to the finding by the Global Forum for Health Research (2002) that only 10% of expenditure on health research addresses diseases affecting the world's poorest. This statistic has been used in arguments for more research in African contexts such as western Kenya. Yet, for social scientists, such statistics demonstrate that the meaning of research becomes transformed from a scientific endeavour to being the most accessible means of healthcare for its participants in contexts where health systems are unable to meet the demands of its population (Fairhead, Leach, & Small, 2006; Hardon et al., 2007). Whether these official statistics are employed to justify increased research or to demonstrate that a sanitised version of science (see Callon & Rabeharisoa, 2003) cannot be conducted in locations where research becomes equated with healthcare, these official statistics have been argued to underestimate the everyday reality of hunger, poverty and death (Krishna, Kristjanson, Radeny, & Nindo, 2004). Furthermore, such statistics cannot capture the lived experience of those tasks with collecting data in western Kenya, where they are likely to encounter two out of ten people who are HIV positive and frequent deaths, ill-health, orphans, poverty and scarce access to basic healthcare needs (Nyambedha, 2008).

For data collectors, it is not only that their everyday working lives were spent in these conditions but they are also tasked with practising an interpretation of bioethics which was not necessarily their own. The findings of this study will show that most data collectors valued the principles of justice and beneficence over autonomy, the preferred ethical principle of their employing institution. This paper will show that such different bioethical leanings were not on the grounds of discordance between ‘African’ and ‘Western’ cultures. Rather the differences between data collectors views and institutional bioethical priorities was related to their position at the coal face of implementing bioethical guidelines. This paper draws attention to their frontline position by focussing on factors which they reported to have shaped their daily bioethical practice. After presenting an outline of the principles based approach to bioethics this paper will introduce the methodological and theoretical approach used in generating data in this study, before reporting on data collectors experiences of living these statistics.

Bioethics in principle

Academic examinations of bioethics reflect a complicated field of study, comprising of multiple definitions of bioethics, within competing ethical positions. Despite the complexity of the bioethics project, research institutions generally adopt a principles based approach for their governance and regulation. Hence, this paper will use a principles based approach in its discussion of bioethics. This approach defines bioethical conduct by four principles: respect for individual autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice (Beauchamp & Childress, 2001). Each of these broad principles represents a moral duty that should, in both theory and practice, be weighed against other duties, in resolving ethical dilemmas. This paper will examine the practice of these principles from a data collectors perspective but first it will discuss some of the perceived advantages of principlism for research institutions.

For medical institutions seeking to incorporate an ethical schema to structure its research, the principles based bioethics approach is argued to hold many practical advantages. Unlike like other bioethical approaches, such as virtue ethics, principlism is seen to provide relatively simple and resource efficient answers to bioethical questions (Widdows, 2007). For instance, it allows researchers to produce (if called upon) signed consent forms from research participants, as tangible evidence that ethics have been ‘done’ (Boulton & Parker, 2007; Marshall, 2006). Producing this type of evidence is valuable in numerous ways. Notably, principlism allows for regulatory frameworks and governance structures to monitor and record these supposed ethical outputs. Hence, authors such as (Strathern, 2000) suggests that the major appeal of principlism is its compatibility with an increasingly bureaucratised, ‘audit culture’ within research organisations. This documentation of ethics holds other types of currency in attracting additional funding, publishing research findings and permitting drugs, interventions and research outcomes to receive government approval (e.g. FDA approval) (Dawson & Kass, 2005). This approach also conveys a general sense that certain apparatus (e.g. Community Advisory Boards, Research Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards and Good Clinical Practice training) facilitates ethical practice. This in turn provides senior researchers, funders and other institutions with assurances that ethical research is happening – without having to witness precisely what practising ethical research entails (Devries, Turner, Orfali, & Bosk, 2006) or indeed, who is practising it (Haimes, 2002; Ricoeur, 1992). Thus, adherence to the principles based bioethics approach can be seen to mitigate much of the ethical and moral labour, which can accompany medical research. Research organisations need not invest as much ethical deliberation as might be required from other ethical approaches.

One of the most attractive features of principlism are its claims to be universal in nature (Emanuel, Wendler, Killen, & Grady, 2004) and its purported abilities to standardise and harmonise ethical conduct across a number of different locations and contexts (Petryna, 2005, 2009). Such claims made by advocates of principlism are attractive as institutions increasingly conduct simultaneous multi-sited and multi-national research. It is argued that these features are some of the main reasons why a principles based approach is the dominant version of bioethics found in research institutions (Wendland, 2008).

Yet, the assumption that establishing governance and regulatory structures can ensure that a certain approach to bioethics is practised in a vast array of locations and contexts has been widely criticised (e.g. Borry, Schotsmans, & Dierickx, 2006; Hellsten, 2008; Holm & Williams-Jones, 2006; Levitt & Zwart, 2009). While its claims to universality might appear a magic bullet, those examining bioethical practice have pointed to the role of institutional cultures in shaping bioethics by for instance, strategically upholding one principle over another, regardless of circumstance and without ethical deliberation (Dziak et al., 2005; Silverstein, Banks, Fish, & Bauchner, 2008). While bioethics might be interpreted as a broad set of ethical principles it is often narrowly conceived by research institutions with consequences for those who are tasked with practising it – the frontline data collectors.

The dominance of autonomy

As noted by Strathern (2000), most research institutions emphasise bioethical principles which are easily audited. Hence, the focus on the principle of respect for autonomy which can produce evidence, in the form of signed consent forms. This observation, by Strathern and others, provides an explanation for the dilution of bioethics; from arguments and complexities found in the broad theoretical concept of respect for autonomy, to limited concerns about information provision and readability of consent forms (Corrigan, 2003). Furthermore, prioritising autonomy often occurs at the expense of other equally important bioethical principles. Additionally, such a narrow focus on autonomy is seen to ignore structural injustices embedded in some research contexts, such as the aforementioned high levels of unemployment, deprivation, and the absence of basic human rights and their violent manifestations on everyday life and ethics (Farmer & Campos, 2004). For instance, the inclusion of such details might lead to consideration of processes such as ‘structural coercion’ (Fisher, 2014) i.e. not only whether consent forms were signed but rather the structural factors which make ‘volunteering’ to research the most amenable access to healthcare for much the world's poor (see Fairhead et al., 2006; Folayan & Allman, 2011; Folayan, Mutengu-Kasirye, & Calazans, 2009; Stewart & Sewankambo, 2010). Such arguments provide weight to ideas that abstract notions of bioethics can extend beyond discussions of autonomy (e.g. Das, 1999), and that the details of everyday life shapes the ethical landscape in which research is practised (e.g. Austin, 2007; Brosnan, Cribb, Wainwright, & Williams, 2013; Fassin, 2008; Kelly, 2003; Kleinman, 1999; Turner, 2009).

Bringing data collectors into view

Although important, most critiques of bioethics rarely engage with the perspectives of frontline research actors such as data collectors. However, there are a few examples of studies which have sought to elicit data collectors' views on their experience of practising bioethics. For instance in Philadelphia, True, Alexander, and Richman (2011) argued that frontline data collectors in their study were generally ambivalent in practising bioethical principles. These data collectors interpreted principles based bioethics as upholding institutional goals to produce data above their safety and the needs of the deprived community members they encountered. Writing from another American context, Fisher (2006) observed a disconnect between the ethical values of data collectors in recruiting and retaining human subjects, and principles advocated by their institution. The data collectors in this hospital-based study, identified their ethical dilemmas as a dissonance between their values and institutional ethical priorities. Furthermore, both studies make it clear that frontline data collectors faced considerable ethical labour, which institutionally derived bioethical priorities did not mitigate. On the contrary, these studies have demonstrated that a narrow interpretation of bioethics contributed to data collector challenges.

These papers, examining the views and positions of American data collectors, are particularly instructive to this discussion of bioethics in two main ways. Firstly, they demonstrate that many of the issues to be discussed in the findings of this paper are not exclusive to an African context. In so doing, these papers allow scope for this examination of African data collectors to move beyond accounts of ‘African culture’ and/or ‘African ethics’ as the primary lens in accounting for differences between theoretical and abstract discussions of bioethics and its practice. Instead, these American studies suggest a commonality between frontline data collectors in different geographical and economic contexts. Most notably they focus on ‘the who’ – the employees tasked with implementing institutional interpretations of ethics, which are at times discordant with their own personal views and everyday experiences. Secondly, these papers reiterate the value of studying bioethics in practice. This paper is focused on data collectors and their experiences of practising bioethics, in contexts which are often physically and economically distanced from institutional board rooms and headquarters.

Theoretical approach

Writing in Oneself as Another (1992), Ricoeur has argued that it is not only important to discuss what ethics is but also to explore who is undertaking a particular practice to gain greater insights into their rationale. While this paper consists of sociologically informed empirical data collected in western Kenya, it is also broadly guided by Ricoeur's philosophy of ethics. Ricoeur (1992: p. 90) argues that there is often too much emphasis on ‘the what’ and ‘the why’ in ethics – what action has taken place and why. Ricoeur does not dismiss the value of these types of enquiry but insists that they are insufficient without an understanding of ‘the who’ – who is undertaking the action in question. In doing so, Ricoeur asks us to consider the pivotal nature of the relationship between action and agent in the production of ethical practice and perspectives (1992: p. 91). From a Ricoerian position, data collectors are not merely passive recipients of institutional priorities, their values and how these are practised, are integral to our understanding of bioethics in practice.

Ricoeur draws on authors such as Arendt (1958), Levinas (1969) and Weber (1968) in arguing that ethics should be considered a tripartite relationship between ‘the self’, ‘the Other’ and ‘the institution’. He uses the term ‘institution’ to mean more than organisations but also societal structures. He is particularly interested in agency and the extent to which individuals have the power to fulfil their ethical aims and motivations. The notion of ‘the encounter’ has particular significance for Ricoeur. He explains that in everyday encounters individuals are confronted by the needs of the Other. He argues that if responding to this need means breaching institutional rules, then individuals will be less concerned with institutional ethics and more interested in the request presented to them. In this way, institutions do not hold complete power over ‘the self’ – individuals hold power in their everyday practices. He argues that for most individuals, their primary aim is to be “good”, to fulfil their self-esteem. Ricoeur (1992) argues that being confronted with the needs of the Other has the power to shape the ethical policies of institutions from below. Ricoeur draws on Levinas (1969), who argues that the motivation for enacting good deeds is out of a sense of responsibility to the ‘Other’. The ‘Other’ in this sense becomes apparent in the face-to-face encounter with another person. For Levinas, it is during this encounter that what is good can be ascertained; the good in one situation is not the same good for all encounters.

Furthermore, Ricoeur argues in favour of engaging with (and not ignoring) the discordant interpretation of ethics between individuals and institutions, to undercover the motivations influencing individual actions. From this interpretative perspective, judgements of what constitute ethical behaviour are secondary to understanding individual intentions. This engagement with different interpretations of ethics has important methodological implications to this examination of data collectors which will be discussed further.

Methods: collecting data on data collectors

The findings in this paper are based on an ethnography conducted in western Kenya during which data was collected over a two-year period from 2007 to 2009. This study examined data collectors involved in five different medical research projects which varied by their research design (e.g. randomised control trials) and their disease focus (e.g. malaria or HIV/AIDS). These projects involved different national and international research partners including collaborations between academic institutions, public health bodies, pharmaceutical companies and non-government organisations. While these projects had different configurations they were governed by a principlist approach to bioethics. The data collectors in these projects were recruited locally and were all successfully in meeting the minimum requirements of their research institutions. They were expected to be educated to secondary school level and the majority were aged between 18 and 35 years old. They were predominantly of Dholuo ethnicity, as were most of the local population which was seen to provide research projects with individuals who were familiar with the cultural and geographical environment of data collection. In this study there were an equal number of men and women data collectors. During this study, the everyday practices of data collectors were examined to explore their views on ethics. This term was broadly defined in this study but included their perspectives on bioethics.

Ethical approval

This study of frontline data collectors involved gaining multi-institutional ethics approval. Ethical approval was sought from four different institutions which included my academic institution in the UK, a research institution in Kenya and two separate international organisations conducting research in western Kenya. The length of this process varied greatly between institutions from one to twenty four months. Additionally, permission was sought from Senior Researchers (e.g. Principal Investigators) involved in the five aforementioned research projects before seeking the individual consent of data collectors.

Interviews and focus group discussions

This study involved multiple methods, including observations, interviews and a graphic elucidation technique. Data collectors were accompanied during their working and non-working lives. This involved observing the collection of samples and the conduct of interviews between data collectors and their participants. In seeking to gain data collectors' perspectives of their everyday lives and views on ethics, this paper accepts that there are multiple ways to perceive, understand and discuss the world (e.g. Stanley & Wise, 1993). Within this approach, my informants' accounts of ethics are not regarded as objective but rather they were seen valuable in illuminating a particular view and position on ethics.

Data collectors were interviewed as part of Focus Group Discussions (FGDs). I used FGDs as an introduction to my aims and to gain insight into the dominant themes about research practices. I conducted seven FDGs with between three and five data collectors employed on the same projects, so they were already acquainted. All FGDs were conducted away from the main field station and were approximately 90 min in length. All FGDs were audio recorded and transcribed.

In-depth Interviews (IDIs) were used to explore significant themes from FGDs and observations. I conducted 31 IDIs, which were longer than FGDs, ranging from 45 min to 3 h, and they were conducted in a variety of places chosen by interviewees: cafés, hotel bars and private homes. These interviews generally occurred outside working hours and were less structured than FGDs with more focus on eliciting personal insights and perspectives on fieldwork experiences. I gave particular attention to contrasting views to those expressed in FGDs, and this format allowed for private explanations of personal perspectives without confronting a dominant group view.

All interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist who was unconnected to the field site or the interviewees. I deemed this necessary to maintain informants' anonymity, and they were all informed of this procedure prior to their interviews. Additionally, a quarter of interviews were randomly selected and double-transcribed by an additional transcriptionist. This allowed for any potential errors to be identified and amended, and I checked any discrepancies in these transcriptions. In this paper pseudonyms will be used to maintain the anonymity of those interviewed.

The data analysis in this study was informed by interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) (see Smith & Eatough, 2006; Smith & Osborn, 2003). Within sociology, IPA is closely related to interpretative traditions which argue that researchers cannot capture the world directly but only study representations of it as negotiated in social interactions with others (Atkinson, Hammersley, Denzin, & Lincoln, 1994; Mills, 1959). IPA aims to produce emic (insider) and etic (outsider, interpretative) accounts of a phenomenon (see Flowers, Smith, Sheeran, & Beail, 1997; Reid, Flowers, & Larkin, 2005). Therefore, some features of IPA resonate with other sociological approaches such as ‘grounded theory’ (Starks & Trinidad, 2007). Grounded theory emphasises the importance of allowing themes to emerge from the data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) and through an iterative process, reflecting on and engaging with informants' accounts. This process is referred to as the constant comparison methods by Charmaz (2006). In this way, both IPA and some features of grounded theory encourage the researcher to consider their relationship to the data they have collected and to pursue internally divergent positions with datasets. IPA holds appeal to sociologists wishing to combine emic and etic perspectives in inductive investigations, particularly in the research of sensitive issues among marginalised populations (see James & Starks, 2011; Jarman, Walsh, & De Lacey, 2005; Starks & Trinidad, 2007). A graphic elicitation technique is an example of how I employed IPA in this study which will be discussed in further detail.

Graphic elicitation technique

Graphic elicitation techniques are usually employed by social scientists researching particularly sensitive subjects (Crilly, Blackwell, & Clarkson, 2006). In its original format, this method requires that researchers produce and present illustrations to research participants (Galman, 2009). Instead, in this study I employed an illustrator who was unfamiliar with this location and context. The illustrator created visual representations of my initial observations, conversations and data gained during interactions with data collectors. These illustrations were shown to data collectors to elicit their responses, and then used to modify representations. Discussions of illustrations with data collectors generally took place informally within a small group. From such discussions, the modification of illustrations continued until a general consensus among data collectors that the illustrations produced were representative of their views and that they had nothing more to add to what was produced. These illustrations allowed for data collectors' perspectives and interpretations of this sensitive topic to be anonymously presented (Bagnoli, 2009). So while the illustrations aimed to be representative of everyday events, they also protected data collectors' and clinical research participants' identities. The illustrations informed future interviews with data collectors and senior researchers, which proved valuable in interpreting and analysing this data. For these reasons, I used this method as a key source of data, informing the reflexive and analytical processes involved in the production of data.

Findings: the everyday realities of practising bioethics

The research encounter

The data collectors examined as part of this study received training in Good Clinical Practice (GCP). This involved being made aware of the procedures for collecting data, including how to store samples safely. As part of this training, ethical research conduct was also discussed. This focused almost entirely on respect for individual autonomy and in particular, the importance of having a completed consent form from research participants. Data collectors were also told about the importance of conducting themselves respectfully and being considerate to research participants.

In keeping with their GCP training, the data collectors I observed ensured that consent forms were completed by individuals prior to their involvement in research. Research institutions often placed great emphasis on data collectors following the consent procedure. Data collectors reported numerous challenges associated with this process, including gaining verbal consent from several family members for an individuals' research participation. However, most data collectors argued that although challenging, gaining consent for research participation presented them with the fewest ethical dilemmas. Instead, they argued that most of their ethical predicaments occurred after consent had been obtained. This experienced influenced the value they placed on the notion of autonomy as the central facet of ethical practice. The following illustration was produced with data collectors' involvement and provides an example of such everyday experiences in this context.

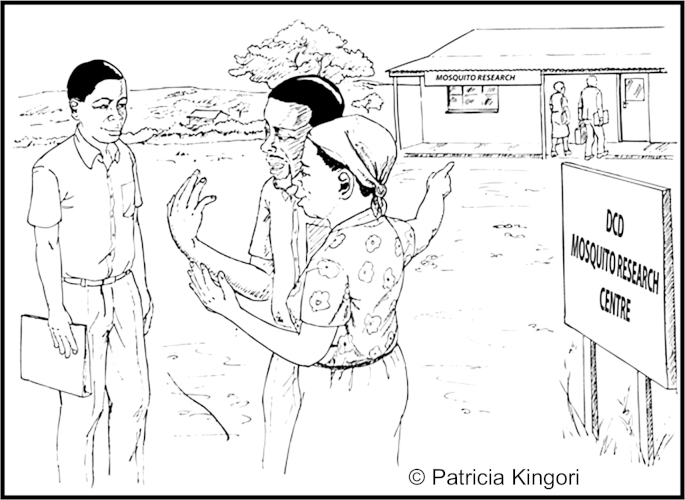

Fig. 1 presents an encounter between a data collector and two community members, standing outside of the field station of a research institution. The data collector is shown holding a folder which contains information about the sampling criteria, recruitment targets and the consent forms given to him by the research institution. The folder is closed and the fieldworker is shown be patiently waiting for a chance to explain the research protocol. In Fig. 1, the community members are shown to be agitated in asking for access to better healthcare. They regard the research institution as being able to provide healthcare to the whole community and not only to research participants.

Fig. 1.

“You must help us! Why can't all have better health?”

The data collectors developing Fig. 1 wanted it to reflect a number of features which they felt provided important insights into bioethics in practice. Firstly, they wanted attention given to the geographical context of their data collection. In particular, they wanted the illustration to show very few roads and a topography which made travelling difficult. It was also important to highlight the distance from other facilities – the next building in Fig. 1 is shown to be far away. Hence, this field station represents the most accessible means of healthcare in this location. While the potential for healthcare is physically close it is also unobtainable for those not part of research. This was reported to create pressure on data collectors who felt that the geography and inaccessibility of healthcare (both physically and economically) meant that their presence carried greater responsibility in this context. An additional feature of this illustration is the distance between the data collectors and senior researchers. It shows two smartly dressed senior researchers walking into the research facility, disengaged from the exchange taking place at the forefront of the illustration.

Data collectors co-producing Fig. 1 also wanted it to represent their experience that not all community members were interested in the aims of research. The facility shown focused on mosquito research but community members were unhappy that it did not cater for human or general healthcare needs. For data collectors, this lack of interest in the details of research challenged institutional procedures, which emphasised providing information prior to consent to inform the decision-making process of research participation. Data collectors argued that many participants wanting to be involved in research had made their decision before being given specific research details. Furthermore, any insistence on the part of data collectors that potential participants should pay careful attention to information sheets often increased suspicion and undermined trust in the verbal assurances given about the benefits and safety of their participation. Instead data collectors argued that a range of other factors, which were not captured in a principles based understanding of autonomy, influenced whether community members agreed to be research participants, including whether the data collectors were ‘good’ people. In particular, having witnessed the needs of the local population, data collectors were expected to be motivated to try and improve them. Such subjective criteria directly affected obtaining consent in practice and were reflective of a different ethical priority made about data collectors' performance which came from the communities in which they worked. These points will be examined further in the next illustration.

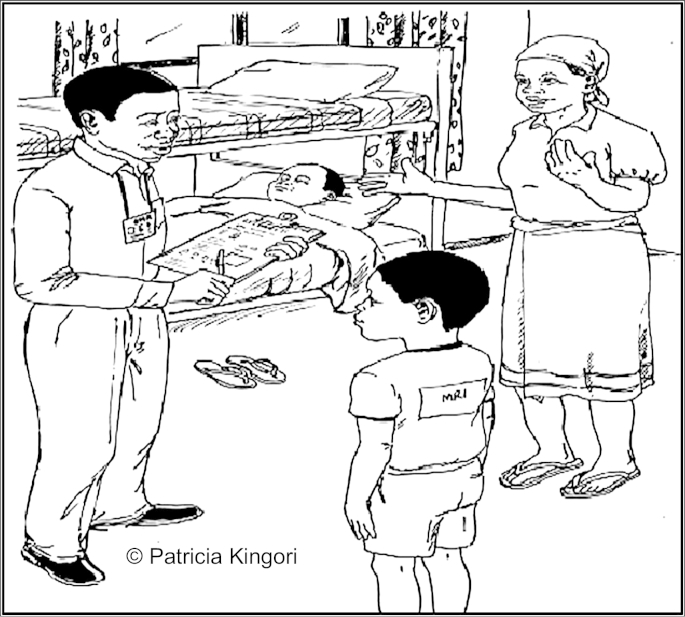

Fig. 2 presents another example of data collection in an ethically charged research encounter. This illustration shows a data collector in the home of a research participant (the boy standing). It shows the data collector having completed the informed consent procedure and it about to collect data (using the clip-board in his hand). During this process, the data collector is alerted to a critically ill child. However, unlike his sibling, the sick child is not enrolled into medical research. Therefore, the healthcare benefits which could be conferred to the research participant in the event of ill-health cannot formally be extended to his sick brother. Generally, data collectors had neither the authority to openly flout institutional policy nor additional resources to meet such requests. Nevertheless, the children's mother appeals for his help as she lacks resources and recognises that to get healthcare she needs the data collector's personal intervention. While this example shows a child in need, data collectors commented that they regularly received similar requests from the local population.

Fig. 2.

The research encounter: what is the right thing to do?

In developing Fig. 2, data collectors emphasised the importance of reflecting the economic disparity between the local population and themselves. For instance, the data collector is shown wearing formal ironed clothes. In comparison, the mother and child are dressed informally, wearing flip flops in a sparsely furnished home (bunk-beds in this context are rare and it is used in this illustration to represent a sibling relationship between the children). This for data collectors was reflective of their reality in doing research, as they were seen as representatives of organisations with vast resources and which increased expectations of their assistance in these encounters.

In the following quotation, Fred supports the themes presented in Figs. 1 and 2. He explains the value of free healthcare, in a population prone to high rate of morbidity and mortality, and where a quarter of children die before their fifth birthday:

…If these mothers had money they would be taking their kids to health facilities. But then it's because of the poverty level that's why they want to get involved in a study, because like in a study all who get involved, the kids get free medication so they don't have to go round looking for money to bring their kids to the hospital…I mean this is an area that is prone to diseases, like diarrhoea, malaria…the level of malaria has gone high, diarrhoea it's serious.

Fred, Data Collector, in-depth interview

Fred's comments about the meaning of research in this context were shared by many data collectors. This process of ‘structural coercion’ – where broader contextual factors, act upon individuals to compel them to enrol in research – is a common finding in numerous studies in locations characterised by weak public health infrastructures or no universal access to healthcare (Fisher, 2014). What becomes apparent in these contexts is that research offers a means for the poor to improve their health and well-being (Abadie, 2010).

Yet, in abstract discussions of bioethics, the motivations outlined in Fred's quote are problematic. They were often discussed as inhibiting the free will and autonomous decision-making of individuals, making them more vulnerable to consenting to studies which could cause harm (e.g. Appelbaum & Lidz, 2008). Additionally, such motivations on the part of research participants are regarded as misconceptions of research aims, as having a therapeutic function when research seeks a scientific goal (Henderson et al., 2007). Hence, notions of therapeutic misconception and the inducement of individuals are discussed as challenges to research in contexts of poverty. Ideas of therapeutic misconception are generally premised on a knowledge-deficit model – that individuals lack the right type or amount of information in their decision-making. Therefore, the solution to this misconception has been to invest more in the design and clarity of consent forms and information sheets (e.g. Fitzgerald, Marotte, Verdier, Johnson, & Pape, 2002), a strategy which overlooks the research contexts and the type of statistics presented earlier in this paper but preserves an emphasis on autonomy as the solution to ethical challenges in the conduct of research.

Like Fred, most data collectors involved in this study were not concerned that healthcare benefits were among the primary motivation for research participation. Data collectors felt that the treatment and attention that participants received was far superior to those given at healthcare facilities, such that the attraction of research participation was not only for treatment but also a preference to the care given to research subjects. For this reason, many data collectors argued that having witnessed first-hand the living conditions of community members, the decisions of mothers to enrol their children into research was pragmatic and sensible given their scarce resources.

While recognising these motivations for research participation, data collectors were specifically employed to obtain data for research and scientific purposes. Yet, implementing this distinction in everyday data collection was difficult and created tremendous stress, anxiety and feelings of guilt. In the following quote, Fiona explains that these negative feelings exist in part because many data collectors felt that more could be done by their wealthy research organisations in this context. So that while data collectors often defended their research institutions in public discussions with community members, in private many data collectors were in agreement with that more could be done for them. Here she explains a data collection experience:

…like there is one where I went to and a girl and she can't, she's deaf girl, she can't walk, she's weighing around 20 or 30 kilos and she's 20 years…she can't do anything. The mother has to use clothes…as her potty. So the mother is pinned down with this daughter.

And you look at her and you really feel I wish I could do something for her. You know you really look at it as in what can I really do? Do I give out all my salary?

So we really do wish the program had something [to help]. Such that it's only not about data, picking that particular information you want and you go. You need this person alive to be able to collect that data. You're not going to collect data from a corpse.

Fiona, Data Collector, in-depth interview

This quote resonates with themes presented in the illustrations produced with data collectors and suggests that an explanation for the frustration of data collectors might lie in what a Festinger (1957) describes as a ‘cognitive dissonance’ between what data collectors were forced to do publicly by their institution (only extend certain types of assistance under particular circumstances) and what they privately wanted to do (‘do something’ to help in a range of encounters). What Fiona articulated in this quote is a desire for consistency in her ethical beliefs, attitudes and actions. For most data collectors interviewed, it was such scenarios which created their everyday ethical dilemmas and not notions of autonomy or lack of attention to the consenting process. The absence of formal procedures to support their ideas of justice undermined the ethical position of some research institutions in the eyes of data collectors. In the following quote, Frank openly questions the humanity of such a narrow interpretation of bioethics. He argues:

…aren't these people also human beings who are doing this [producing bioethical guidelines]? Do they believe the people we get the data from are robots? And…even if they [research participants] were robots they need oil……to lubricate, to function.

Frank, Data Collector, In-depth interview

Frank's interpretation of bioethics, as lacking in humanity in practice, is far what from its historical intention (e.g. Nuremberg and the Declaration of Helsinki) and yet his views were supported by most of the data collectors interviewed. For instance, in discussing Fig. 2, some data collectors suggested that if they decided not to intervene to assist the sick child, while they might face community condemnation and experience feelings of personal guilt, they were less sure of any formal institutional repercussions; as they had respected the notion of autonomy in consenting and community members were made aware of the terms and conditions of research when they agreed to host it. These sentiments further support arguments of cognitive dissonance between their private views and expected public actions. They also show that the bureaucratic institutional aims in advocating a narrowly conceived principles based approach are inconsistent with a full appreciation of the unique circumstances of everyday life, which making it impossible for universal approaches to incorporate such idiosyncrasies. This observation is reminiscent of Carol Heimer's (2001) work on “cases” versus “biographies” and the challenges of attempting to standardise and routinise everyday life.

The theory of cognitive dissonance provides valuable analytical insights into the position of data collectors and yet for Ricoeur it is important to stress that individuals do not passively experience these disconnects between their ethical values and actions and accept an institutional power over their ethical values. Rather Ricoeur, like Levinas (1969) argues that individuals actively seek ways to enact their values especially when these are spurred on by witnessing the needs of others. For example, Häggström, Mbusa, and Wadensten (2008) employed Ricoeurian theory to demonstrate that the ethical dilemmas of Tanzanian nurses were frequently the result of tensions between what they were obliged to do and what they felt was the good way to act towards the patients they faced in resource-poor hospital settings. In such dilemmas, whenever possible, nurses prioritised the care of their patients over institutional policies. In so doing, they created informal policies and a disparity between institutional ethical policy and their ethical practice.

In many situations data collectors suggested that they felt a personal moral obligation (which they defined as a desire to act according to their values) to provide assistance when they encountered those in need and also when it was asked of them. This particular obligation generated in immediate and face-to-face contact between the data collector and the needy, resonates with an important feature in Ricoeur's ethical theory. Ricoeur argues being confronted with the demands of another, acts to share the problem with the witness. The challenge of this encounter not only belongs to the person experiencing it but it is transferred to the conscience of the witness to also become their responsibility. In the following quote, Fraser explains the role of his conscience in altering and subverting institutional guidelines which regard providing financial assistance as undermining autonomy. He states:

…if the organisation as a whole refuses or is bound not to contribute to such [need] then I as an individual, I will chip in with something then out of that human heart…You know you can't find someone with a problem and then the research says it should be like this, and then you leave him with his problem…Secondly…as human beings what is your conscience saying? So, we do it for our conscience, for those people [community members]…for the research and for everything else.

Fraser, Data collector, in-depth interview

From a Ricoeurian perspective, this sense of conscience is an important catalyst for data collectors to “remake the world”, in the process spurring on “practical action”. Hence, it can be argued that through conscience and agency, data collectors are altering bioethics in practice from an instrumental focus on autonomy to a broader range of principles which are consistent with their values and ideas of a good life. From Fraser's reasoning it is also clear that while many of his actions appear to be motivated by altruism, there is a strong sense of his protecting his own self-interest, clearing his conscience and maintaining conditions that would make the work he does among that community viable. Hence, it was not only that data collectors felt a responsibility to act, not intervening to provide assistance would jeopardise their ability to collect data in the future. Most data collectors felt that community members would react angrily if their inaction was seen to have contributed to death or unnecessary harm. The interaction presented in Fig. 1 demonstrates an example of how community members often confronted data collectors if they were unhappy with their conduct. An additional dimension to data collectors' predicament was that they irrespective of their actions in relation to the sick child in Fig. 2, they would be expected to continue to collect data from that household for the duration of the research. Consequently, data collectors prioritised solutions which satisfied community members and appeased their conscience while at the same time attempting to maintain their employment. In this way, community expectations were also important in shaping bioethical practice and these were managed through a process of negotiation which involved bargaining, compromising, making arrangements, gaining tacit understandings, engaging in collusion and subverting the rules of research (see Strauss, 1978).

The importance of line managers in shaping bioethics

So far this paper has discussed data collectors' personal views and community influences on their practice of bioethics. However, data collectors emphasised their line managers as important agents in influencing whether institutional guidelines were rigidly enforced. In contrast to earlier depictions of senior researchers presented in Fig. 1, some data collectors argued that their line managers, were aware of their ethical dilemmas and some constructed informal policies and strategies (against institutional concerns about eroding individual autonomy and inducing participants) to provide financial assistance. Here, Faith explains that she does not completely shoulder financial responsibly generated through data collection. She explains that:

…we have petty cash. Like every month Dr. [name withheld] gives 2,000 shillings…so at least these people [in need] have got money…And we don't have to pay for them! We use the petty cash. At times somebody do not have certain medicines…We can always buy for them.

Faith, Data collector, in-depth interview

While these funds were outside of institutional guidelines, for data collectors like Faith, having such support shaped their working practices and mitigated some features of their ethical dilemmas considerably. The two thousand shillings mentioned in the quote is equivalent to approximately £16 and $24 (US). In this location, where most of the population existed on less than a dollar per day, this was a significant amount. Yet, it was a comparatively small sum in relation to the overall expenditure by institutions in conducting research. However, for data collectors, it was not only the financial assistance given by their line manager which was appreciated. The majority of data collectors found being able to speak openly to their line managers about their data collection experiences and difficulties in prioritising consent, was also hugely beneficial to their emotional well-being.

The informal strategies constructed by line managers to assist frontline data collectors were rarely discussed openly because of concerns that they could be interpreted as acts of inducement. So that it was not only data collectors who concealed practices in the name of ethics but so too did a small number of their lines managers. These line managers and senior researchers often empathised with data collectors having to make autonomy their focus when the everyday nature of research in this location demanded that other ethical principles be given greater consideration. In the following quote, a senior researcher describes her feelings about inducements and coercion as misplaced and dehumanising in practice. She argues that:

The heart and the research…should we ask them [data collectors] to de-link those two things and just move ahead…move in and get out? I mean, really my perspective would be, we are humans. We can't just walk to somebody's [household] compound and find that they are riddled with problems, and we assume this is business as usual and just move and begin doing the research the way it is. It's easy for somebody sitting in an office; someone wants to imagine that that's what you should do…to say from a mechanical standpoint, “No, you should not give out anything”. That's why I know we sit and we go to these ethical committees and they sit somewhere and then make decisions, but at times those decisions cannot really hold…this can't just work…

Evelyn*, Senior Researcher, In-depth interview

This paper has presented the frustrations of data collectors but this quote reflects the irritation of a senior researcher in adhering to bioethics in practice. It is valuable because it supports the perspectives of data collectors presented in this paper; that ethical research demanded more than concerns about autonomy. This quote suggests that concerns about inducements and coercion were felt to be over-stated. It also suggests that the closer research actors were to the coal face of data collection, the greater the tension between a narrow interpretation of bioethics and one which is malleable to the realities of everyday life. This observation has been supported in Kenya as in other parts of the world.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper has shown that while from an institutional perspective, the instrumental adoption of autonomy might be valuable in mitigating some of the ethical labour involved in conducting research, it did not alleviate the ethical dilemmas encountered by data collectors in this study. Hence, data collectors bioethical practice were contingent on a number of different factors which were not accommodated by a narrow focus on autonomy. The factors which shaped their quotidian experiences and ethical practice included the socio-economic context and demands from the local population. These factors converged in the research encounter which often conferred responsibility to data collectors and appealed to their conscience to take practical action. The influence of socio-economic and larger structural factors in shaping data collectors practices is not unique to this study. It was also a finding of numerous other studies conducted in a variety of geographical locations. These studies also found that in contexts where healthcare resources were scarce, the aims of research were transformed into a means to gain access to healthcare. This had an influence on the consenting process. Like the data collectors in this study, other studies have shown that ‘structural coercion’ means that the decision to part in research is only partially informed by the details contained in informed consent forms (e.g. Fisher, 2006; True et al., 2011).

However, there are a number of crucial differences between the data collectors presented in this paper and those in some the aforementioned studies. Data collectors examined as part of this study operated outside of hospital-based and institutional settings. This meant closer and more intimate encounters with research participants and community members. Data collectors role involved them making home visits, meeting the family members of research participants and witnessing first-hand and on a daily basis their living conditions. It was this proximity and coming face-to-face with the reality of the startling statistics which defined their encounters and altered their ethical imperatives. In these home visits they were asked to be more than employees of a research institution but rather to be human and empathise with those in need. In this way, the ethical theories of Ricoeur have been important in analysing the significance of these types of encounters and their influence of data collectors interpretation and practice of ethics.

The graphic elucidation technique has been very important as a methodological tool but also in bringing the accounts of data collectors into view. The illustrations co-produced with data collectors offer an example of a valuable methodological approach for empirical examinations in other contexts. These demonstrated their isolation when making difficult ethical decisions. For data collectors, bioethics in practice differed from the interpretation of bioethics advocated by their institution but it was very difficult for them to effect change in any formal way. However, this did not mean that they did not change institutional policies informally. This paper has provided details of their attempts at shaping bioethical practice by providing small sums of money to research participants and this was at times supported by line managers and senior research staff. The intention behind these actions was not to coerce or induce individuals into research, many data collectors felt that the structural conditions in which they worked were already coercive without their interventions. In providing these sums they were often seeking to appease the demands of the needy and their own conscience and to make the practice of research more viable in a context where it was expected to provide general healthcare provision.

What this paper has shown through the examination of data collectors' everyday practices, is that they were also important for what they allow research institutions not to have to consider – ultimately, the idiosyncrasies of everyday life, the consequences of a narrow focus on bioethics, who and what is involved in the production of data to generate scientific and ethically compliant findings. Although the amount of medical research which takes place in western Kenya makes it a particularly useful location to examine fieldworker ethical perspectives, the findings of this study are relevant to the medical research enterprise in general.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the fieldworkers and senior researchers for giving of their time and sharing their experiences with me. I would also like to thank Salla Sariola, Ruth Horn, Kristina Orfali and the anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Your suggestions have helped this paper enormously. I am also grateful to Ndeithi Kariuki for this help in generating these illustrations. The data used in this article were collected as part of my doctoral research generously supported by the Wellcome Trust Ethics and Society Funding Scheme (WT080546MF). I am grateful to Dr. Catherine Dodds and Professor Judith Green of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for their supervision and support during this process. Last but not least, many thanks to Ben Brandon.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- Abadie R. Duke University Press; 2010. Inside the risky world of drug trial ‘guinea pigs’. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum P.S., Lidz C.W. Twenty-five years of therapeutic misconception. The Hastings Center Report. 2008;38(2):5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt H. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1958. The human condition. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson P., Hammersley M., Denzin N., Lincoln Y. CA; Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1994. Handbook of qualitative research. [Google Scholar]

- Austin W. The ethics of everyday practice: healthcare environments as moral communities. Advances in Nursing Science. 2007;30:81–88. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200701000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnoli A. Beyond the standard interview: the use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qualitative Research. 2009;9:547–570. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp T.L., Childress J.F. 5th ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2001. Principles of biomedical research. [Google Scholar]

- Borry P., Schotsmans P., Dierickx K. How international is bioethics? A quantitative retrospective study. BMC Medical Ethics. 2006;7 doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton M., Parker M. Informed consent in a changing environment. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:2187–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan C., Cribb A., Wainwright S.P., Williams C. Neuroscientists' everyday experiences of ethics: the interplay of regulatory, professional, personal and tangible ethical spheres. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2013 doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callon M., Rabeharisoa V. Research “in the wild” and the shaping of new social identities. Technology in Society. 2003;25:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken M.S. Primary health care initiatives in colonial Kenya. World Development. 1998;26:1701–1717. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Sage; London: 2006. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan O. Empty ethics: the problem with informed consent. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2003;25:768–792. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-9566.2003.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crilly N., Blackwell A.F., Clarkson P.J. Graphic elicitation: using research diagrams as interview stimuli. Qualitative Research. 2006;6:341–366. [Google Scholar]

- Das V. Public good, ethics, and everyday life: beyond the boundaries of bioethics. Daedalus. 1999;128:99–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson L., Kass N.E. Views of US researchers about informed consent in international collaborative research. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1211–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries R., Turner L., Orfali K., Bosk C. Social science and bioethics: the way forward. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2006;28:665–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziak K., Anderson R., Sevick M.A., S.Weisman C., Levine D.W., Scholle S.H. IRBs and multisite studies: variations among institutional review board reviews in a multisite health services research study. Health Service Research. 2005;40:279–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel E.J., Wendler D., Killen J., Grady C. What makes clinical research in developing countries ethical? The benchmarks of ethical research. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;189:930–937. doi: 10.1086/381709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairhead J., Leach M., Small M. Where techno-science meets poverty: medical research and the economy of blood in The Gambia, West Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63:1109–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P., Campos N.G. New malaise: bioethics and human rights in the global era. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2004;32:243–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2004.tb00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassin D. The elementary forms of care: an empirical approach to ethics in a South African Hospital. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feikin D., Nguyen L., Adazu K., Ombok M., Audi A. The impact of distance of residence from a peripheral health facility on pediatric health utilisation in rural western Kenya. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2009;14:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1957. A theory of cognitive dissonance. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J.A. Co-ordinating ‘ethical’ clinical trials: the role of research coordinators in the contract research industry. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2006;28:678–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J.A. Expanding the frame of ‘voluntariness’ in informed consent: structural coercion and the power of social and economic context. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal. 2014 doi: 10.1353/ken.2013.0018. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald D.W., Marotte C., Verdier R.I., Johnson W.D., Jr., Pape J.W. Comprehension during informed consent in a less-developed country. Lancet. 2002;360:1301–1302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11338-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers P., Smith J.A., Sheeran P., Beail N. Health and romance: understanding unprotected sex in relationships between gay men. British Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2:73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Folayan M.O., Allman D. Clinical trials as an industry and an employer of labour. Journal of Cultural Economy. 2011;4:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Folayan M.O., Mutengu-Kasirye L., Calazans G. Participating in biomedical research. JAMA. 2009;302:2201–2202. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galman S.A.C. The truthful messenger: visual methods and representation in qualitative research in education. Qualitative Research. 2009;9:197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B.G., Strauss A.L. Aldine Transaction; London: 1967. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. [Google Scholar]

- Global Forum for Health Research The 10/90 report on health research 2001–2002. 2002. http://www.globalforumhealth.org/pages/index.asp Accessed 22.08.03.

- Häggström E., Mbusa E., Wadensten B. Nurses' workplace distress and ethical dilemmas in Tanzanian health care. Nursing Ethics. 2008;15:478–491. doi: 10.1177/0969733008090519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haimes E. What can the social sciences contribute to the study of ethics? Theoretical, empirical and substantive considerations. Bioethics. 2002;16:89–113. doi: 10.1111/1467-8519.00273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardon A.P., Akurut D., Comoro C., Ekezie C., Irunde H.F., Gerrits T. Hunger, waiting time and transport costs: time to confront challenges to ART adherence in Africa. AIDS Care: Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2007;19:658–665. doi: 10.1080/09540120701244943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer C.A. Cases and biographies: an essay on routinization and the nature of comparison. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:47–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hellsten S.K. Global bioethics: utopia or reality? Developing World Bioethics. 2008;2:70–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2006.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson G.E., Churchill L.R., Davis A.M., Easter M.M., Grady C., Joffe S. Clinical trials and medical care: defining the therapeutic misconception. PLoS Medicine. 2007;4:11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S., Williams-Jones B. Global bioethics – myth or reality? BMC Medical Ethics. 2006;7:E10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James R.D., Starks H. Bringing the “best science” to bear on youth suicide: why community perspectives matter. In: Burke W., Edwards K., Goering S., Holland S., Trinidad S.B., editors. Achieving justice in genomic translation: Rethinking the pathway to benefit. Oxford University Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jarman M., Walsh S., De Lacey G. Keeping safe, keeping connected: a qualitative study of HIV-positive women's experiences of partner relationships. Psychology & Health. 2005;20:533–551. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S.E. Bioethics and rural health: theorizing place, space, and subjects. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:2277–2288. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National AIDS Control Council Kenya national AIDS strategic plan 2009—delivering on universal access to services. 2009. http://www.nacc.or.ke/nacc%20downloads/knasp_iii.pdf Available. Accessed 12.09.11.

- Kleinman A. Moral experience and ethical reflection: can ethnography reconcile them? A quandary for “the new bioethics”. Daedalus. 1999;128:69–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna A., Kristjanson P., Radeny M., Nindo W. Escaping poverty and becoming poor in 20 Kenyan villages. Journal of Human Development. 2004;5:211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas E. Duquesne University Press; Pittsburgh: 1969. Totality and infinity: An essay on exteriority. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt M., Zwart H. Bioethics: an export product? Reflections on hands-on involvement in exploring the “external” validity of international bioethical declarations. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. 2009;6:367–377. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall P.A. Informed consent in international health research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2006;1:25–42. doi: 10.1525/jer.2006.1.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills C.W. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1959. The sociological imagination. [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedha E.O. Ethical dilemmas of social science research on AIDS and orphanhood in western Kenya. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petryna A. Ethical variability: drug development and globalizing clinical trials. American Ethnologist. 2005;32:183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Petryna A. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 2009. When experiments travel: Clinical trials and the global search for human subjects. [Google Scholar]

- Reid K., Flowers P., Larkin M. Exploring lived experience. The Psychologist. 2005;18 [Google Scholar]

- Ricoeur P. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1992. Oneself as another. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M., Banks M., Fish S., Bauchner H. Variability in institutional approaches to ethics review of community-based research conducted in collaboration with unaffiliated organizations. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2008;3:69–76. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.2.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.A., Eatough V. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Breakwell G., Hammond S., Fife-Schaw C., Smith J.A., editors. Research methods in psychology. 3rd ed. Sage; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.A., Osborn M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: SMITH J.A., editor. Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to methods. Sage; London: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley L., Wise S. Routledge; London: 1993. Breaking out again: Feminist ontology and epistemology. [Google Scholar]

- Starks H., Trinidad S.B. Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:1372–1380. doi: 10.1177/1049732307307031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart K., Sewankambo N. ‘Okukkera Ng'omuzungu’ (lost in translation): understanding the social value of global health research for HIV/AIDS research participants in Uganda. Global Public Health: An International Journal for Research, Policy and Practice. 2010;5:164–180. doi: 10.1080/17441690903510658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathern M., editor. Audit cultures: Anthropological studies in accountability. Routledge; London: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1978. Negotiations: Varieties, processes, contexts, and social order. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T. 1993. Medical services in western Kenya since 1900: Missionaries, colonials, and Africans. [Google Scholar]

- True G., Alexander L.B., Richman K.A. Misbehaviors of front-line research personnel and the integrity of community-based research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics: An International Journal. 2011;6:3–12. doi: 10.1525/jer.2011.6.2.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner L. Anthropological and sociological critiques of bioethics. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. 2009;6:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- UNHABITAT . UNHABITAT; 2006. Kisumu declared world's first Millennium City.http://www.unhabitat.org/content.asp?cid=2275&catid=5&typeid=6&subMenuId=0 [Online] Available. Accessed 13.03.09. [Google Scholar]

- Wamai R. The health system in Kenya: analysis of the situation and enduring challenges. JMAJ. 2009;52 [Google Scholar]

- Weber M. Bedminster Press; New York: 1968. Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology. [Google Scholar]

- Wendland C.L. Research, therapy, and bioethical hegemony: the controversy over perinatal AZT trials in Africa. African Studies Review. 2008;51:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Widdows H. Is global ethics moral neo-colonialism? An investigation of the issue in the context of bioethics. Bioethics. 2007;21:305–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2007.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]