Introduction

In 1980, our group introduced the use of lectin separated E-Rosette depleted (SBA−E−) marrow transplants derived from HLA haplotype disparate parents for the treatment of children with severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) (1,2,3). Early experience, confirmed by centers worldwide (4,5,6), demonstrated that adequately depleted marrow grafts could be administered from haplotype disparate donors without risk severe graft vs. host disease. Early experience with the application with such transplants in patients with leukemia underlined the potential risks of graft rejection or graft failure associated with these transplants (7–11). However, the development of tolerable but more immunosuppressive conditioning regimens coupled with the development of T-cell depleted peripheral blood stem cell transplants has now reduced the incidence of graft failure to less than 2% (12–18). In our experience of over 690 SBA−E− marrow transplants administered from HLA matched related or unrelated donors; the incidence of acute graft vs. host disease in related and unrelated HLA matched graft recipients is 7% and 17% respectively. The overall incidence of chronic graft vs. host disease is also low 3% and 5% respectively in this series. Similarly, for 328 leukemic patients who received HLA-matched related or unrelated transplants of CD34 positively selected peripheral blood stem cells fractionated by the Isolex system, secondarily depleted of residual T-cells by sheep red cell rosetting, 9% of the related and 13% of the unrelated graft recipients developed grade II–IV graft vs. host disease; only 18% and 9% developed any chronic graft vs. host disease (17, 19). Each of these approaches employed grafts administered without post transplant immunosuppression.

Our experience with HLA disparate T-cell depleted transplants in patients for leukemia is more limited. However, among 128 patients receiving transplants from 1- > 3 HLA allele disparate donors, the incidence of acute grade II–IV is 23% and the overall incidence of any chronic graft vs. host is 12%, with only 2% developing extensive chronic graft vs. host disease. In this series the incidence of acute and chronic graft vs. host disease is not altered by HLA disparity. Thus, in both HLA matched and HLA disparate donor recipient pairings adequately T-cell depleted transplants administered without post transplant prophylaxis are now associated with incidences of graft rejection or graft failure that are < 2% and markedly low incidences of both acute and chronic graft vs. host disease. Furthermore, in patients transplanted in first or second remission for AML or ALL, the overall incidence of relapse is also low. In our series, only 8% of patients receiving transplants from related or unrelated matched donors for AML in first remission have developed relapse; 6% have relapsed following transplants for AML in second CR. For ALL, the incidence of relapse following a transplant for high risk disease in first complete remission is 7% and 19% for patients transplanted in second remission.

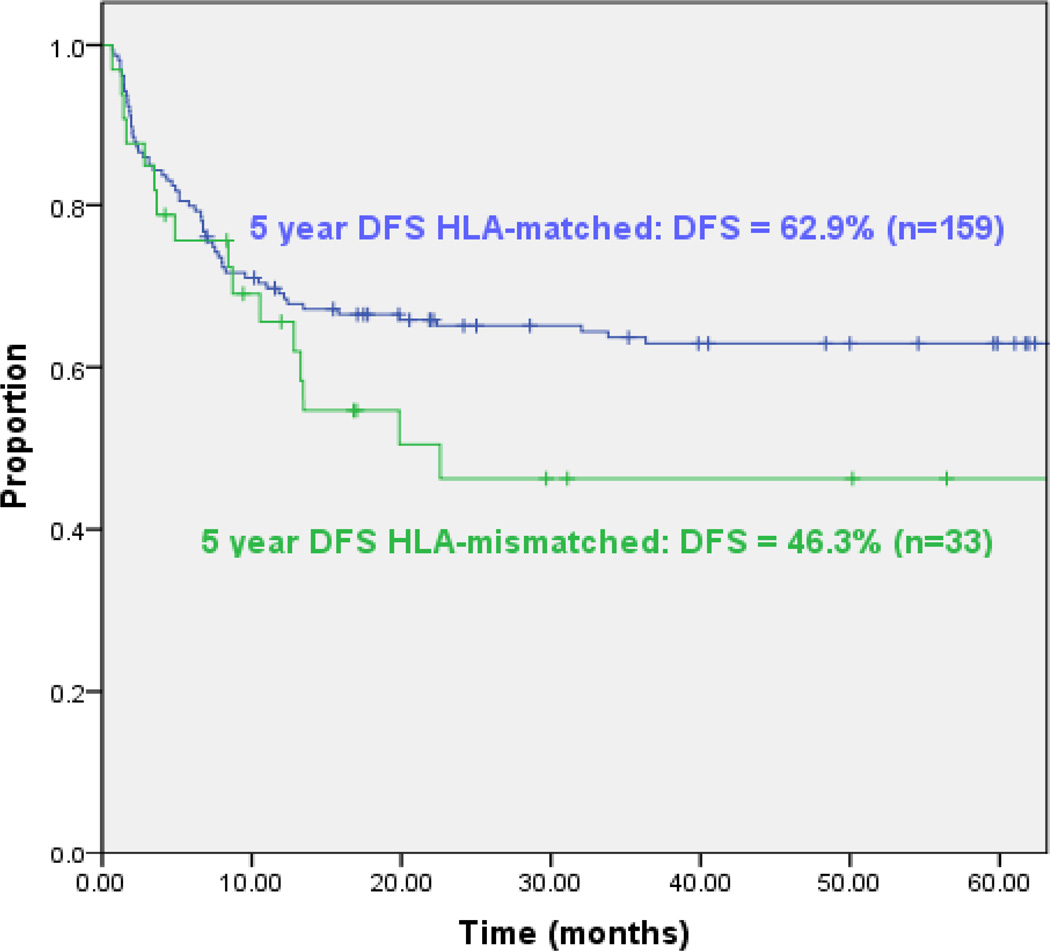

Despite the consistent engraftment and low incidence both graft vs. host and relapse following such transplants, the long-term disease free survival (DFS) continues to be significantly better for patients receiving HLA matched related or unrelated transplants than for recipients of HLA disparate grafts. For example, among our patients transplanted for AML in first or second remission, disease free survival is 63% at 5 years for HLA matched related or unrelated donors but only 46% for recipients of HLA disparate grafts (Figure 1). The differential between HLA matched and HLA disparate grafts is primarily due to the higher incidence of lethal infections associated with HLA disparate transplants. Principal among the infections associated with both more severe and more protracted morbidity as well as a higher incidence of mortality in recipients of T-cell depleted HLA haplotype disparate grafts are EBV induced lymphomas, CMV infections and adenoviral infections. In our series, the incidence of EBV lymphomas following HLA disparate transplants is almost twice that observed following transplants from HLA matched related or unrelated donors (20). The distinctive sensitivity of recipients of T-cell depleted transplants to the development of EBV lymphomas likely reflects the essential role of ongoing T-cell mediated surveillance in individuals chronically infected with EBV. At any time, an estimated 30–100 EBV transformed B cells/ 106 B cells are present in the circulation in normal seropositive individuals (21,22). To control these transformed B cells, the same normal adults maintain populations of T-cells specific for EBV antigens that have been estimated at between 0.5 and 5% of the T-cells in the blood at any given time (23, 24). Thus, extensive T-cell depletion without equivalent elimination of B-cells in the graft can place patients at significant risk of uncontrolled proliferation of donor-derived EBV transformed B-cells in the post transplant period. In contrast, in our own studies, we have found that the incidence CMV activation and CMV disease among CMV-seropositive recipients of HLA-matched related or unrelated T-cell depleted transplants are not different from those that have been reported for HLA-matched unmodified grafts (25, 26, 27). Furthermore, in our series, the mortality rates associated with CMV disease following T-cell depleted transplants in HLA matched related or unrelated recipients are 3% and 4% respectively; rates which do not differ from the 3–8% and 5–10% incidences reported for unmodified HLA-matched related or unrelated grafts (26, 27). In contrast, while the incidence of CMV activation is not different following HLA haplotype mismatched grafts, the incidence of CMV disease and associated mortality is significantly increased. For example, in the Perugia series up to 25% of patients have developed CMV disease and overall 14% of patients have died of these infections (28). Similarly, several groups have reported unacceptably high rates of lethality associated with adenovirus infection among recipients of HLA disparate unmodified and T-cell depleted marrow transplants (29).

Figure 1.

de novo AML in 1st and 2nd Remission @ TCD HSCT, TBI/Thio/Cy or Flu: HLA-matched vs. HLA-mismatched

In previously reported studies, the higher incidence of lethality associated with such infections has been ascribed to T-cell depletion alone (30, 31). However, recent studies, including our own, suggest that the recovery of functional T-cell populations following T-cell depleted grafts administered without post-transplant immuno suppressing drugs is not significantly different following HLA matched versus HLA disparate T-cell depleted grafts (32, 33). Furthermore, the reconstitution of T-cell populations and their function following T-cell depleted grafts is only marginally later than that observed following unmodified grafts (34). These findings suggest that other mechanisms may make important contributions to the enhanced susceptibility observed among HLA haplotype disparate graft recipients.

We hypothesize that the increased and prolonged susceptibility to viral infections observed in recipients of HLA haplotype disparate grafts is to a significant degree attributable to what we call “the constraints of immunodominance” (35). By this we mean that any virus-specific T-cells transferred in a T-cell depleted graft will be derived from an immunodominant population in the donor’s blood and that such cells will only be able to expand and respond to infected cells of the host if they are restricted by an HLA allele shared by the host. Conversely, if they are restricted by HLA alleles unique to the donor, they will fail to recognize virus infected cells in the host. In such a case, effective T-cell responses will not occur until new virus-specific T-cells are generated from donor T-cell precursors developing in the host thymus that are restricted by shared or host-unique HLA alleles. In this brief report, we will present evidence in support of this hypothesis and describe novel approaches whereby this limitation to the success of HLA haplotype-disparate transplants may be overcome.

Adoptive Therapy for Viral Infections Complicating T-cell Depleted Hematopoietic Cell Allograft

Over the past 15 years, several transplant groups have been developing and exploring the adoptive transfer of pathogen-specific T-cells as a therapeutic and prophylactic approach for control of viral infections in the post transplant period. Extensively T-cell depleted hematopoietic progenitor cell transplants provide a particularly favorable platform for examining such therapies since these grafts do not require post transplant prophylaxis with immunosuppressive drugs that can inhibit or eradicate T-cells infused. At our own center, we are conducting a series of trials evaluating virus-specific T-cells for the treatment of patients with documented CMV infections and EBV associated malignancies in the post transplant period. In one of these trials, we are evaluating T-cells, sensitized in vitro with autologous dendritic cells loaded with a pool of overlapping pentadecapeptides spanning the sequence of CMVpp65, in the treatment of patients with overt CMV disease or CMV viremia that has persisted despite at least two weeks of antiviral therapy. In this study, we are evaluating single or multiple doses of CMVpp65 specific T-cells ranging from 5 × 105 −2 ×106 T-cells/Kg (36). Of the 11 patients treated thus far, 9 have cleared their CMV viremia and 8 have achieved remission of CMV disease. Among these patients, we observe that the T-cell infusions are well tolerated without subsequent development of graft vs. host disease. Following the infusions we see an increment in circulating CMV DNA at 24–48 hours after infusions. Thereafter, the CMV DNA is cleared and the frequencies of circulating CTL precursors specific for pp65 increase. Our studies of the T-cells have also demonstrated that the populations detected at 28 days post infusion are CMVpp65-specific tetramer+ T-cells bearing the same V beta family of T-cell receptors dominant in the infused T-cell populations.

In analyses of the CMVpp65-specific T-cell lines to be used in this trial as well as T-cells from other seropositive volunteer donors sensitized with to the pool of CMVpp65 peptides loaded on autologous dendritic cells, we have consistently found that, the T-cells responding to peptides of CMVpp65 are specific for only 1–2 immunodominant viral epitopes presented by 1–2 of the donor’s HLA alleles (37). By quantitating T-cells generating interferon gamma in response to a mapping matrix of subpools of these CMVpp65 15-mers we have been able to ascertain the specific 15-mer peptides eliciting responses and thereafter identify the specific immunogenic epitopes stimulating the CD8+ and/or CD4+ T-cells responses observed. In addition, by loading the identified peptides on panels of target cells, each sharing single HLA class I or class II allele with the donor, we have been able to distinguish the presenting HLA allele for each of the epitopes (37). These studies, conducted on more than 50 normal seropositive donors have demonstrated selective reactivity against no more than 2 epitopes in each of the lines tested. While the T-cell sensitization in vitro permits outgrowth of both CD4 and CD8 T-cells, T-cells reactive against these immunodominant epitopes have been, in the main, CD8 T-cells restricted by an HLA A or B allele. Our findings are not unique. Rather they are consistent with a large body of data derived from evaluations of immune responses in normal seropositive donors latent by infected patients with CMV and EBV. During acute infection, T-cell responses may be generated against a large array of immunogenic epitopes presented by many different HLA alleles expressed by the responding T-cells. However, during convalescence, there is a massive contraction of these responses. As a result, only T-cell responses directed against a very limited number of epitopes derived from the most immunogenic peptides of the virus are sustained (38,39,40). These immunodominant T-cell responses thus provide the basis for the adaptive immunity essential to control of latent infection and resistance to secondary infections. While the basis of immunodominance is still unclear, certain attributes of immunodominant T-cell clones are now recognized: 1) the immunodominant T-cell responses that are sustained are specific for only a limited number of epitopes within highly immunogenic viral proteins (38,39,40); 2) the dominant epitopes induce responses of higher functional avidity as measured by the binding of the T-cells to epitope-HLA complexes (41); 3) these stronger responses induce larger populations of peptide specific T-cells that consitute the dominant response.

Given the fact that seropositive donors latently infected with CMV and EBV may only maintain significant populations of virus specific T-cells directed against 1–2 immunodominant epitopes, it can be reasoned that in T-cell depleted transplants providing overall T-cell doses of 0.5–5 × 104 T-cells/Kg, only such immunodominant T-cells which have frequencies exceeding 1 ×105 would be transferred in the graft. In this situation, such T-cells can be expected to expand and provide early resistance to the host if they are restricted by HLA alleles shared by the recipient. If, on the other, hand the donor T-cells are restricted by HLA alleles unique to the donor they can be expected to be ineffective in eradicating host cells expressing viral antigens. As a consequence, reconstitution of effective immunity would not occur in such patients until new T-cells develop from donor T-cell precursors maturing within the host thymus. In young children, this takes is about 4–6 months. However, among adults, recovery of effective thymopoiesis may take 12–18 months (33,34,42).

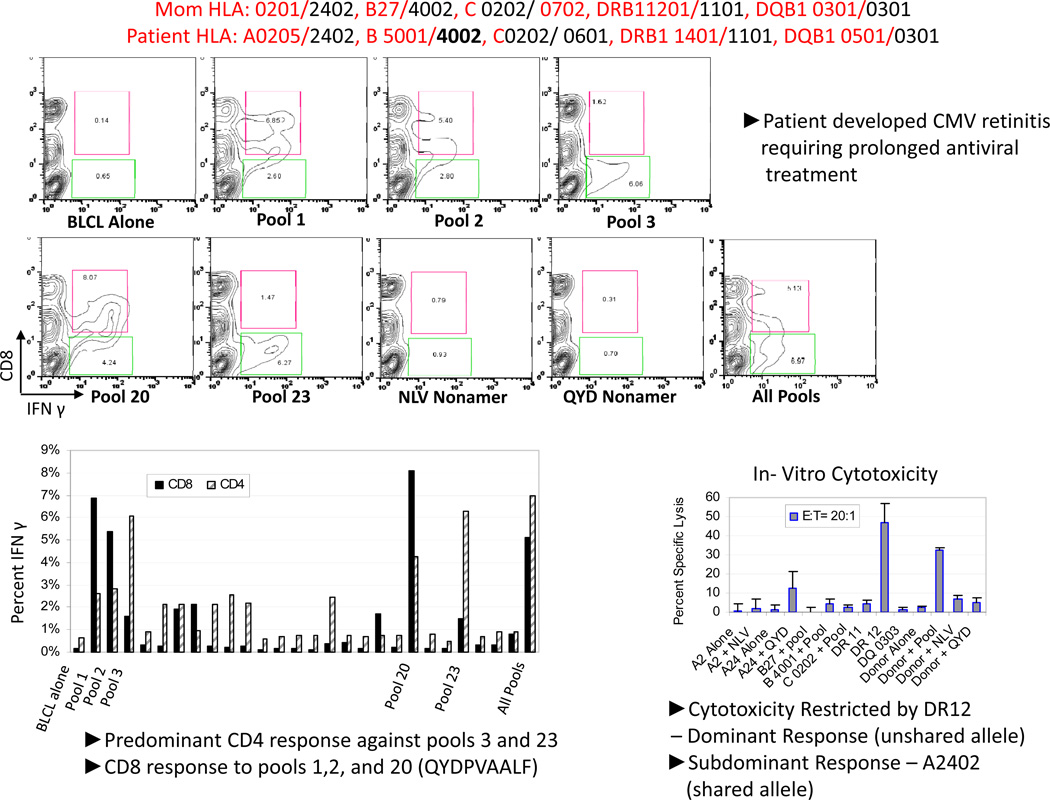

An example of this problem presented in Figure 2. As shown, the maternal donor and transplanted recipient shared an HLA A2402, B4002, C202 and DRB1101. Sensitization of T-cells from this mother with the pool of CMVpp65 led to the development of CMVpp65 specific T-cells that were exclusively reactive against subpools 3 and 23 and peptide 123 shared by these subpools. There was a minor response to pools 1, 2 and 20. Strikingly, the T-cells responding to pools 3 and 23 were exclusively CD4+. Subsequent analysis of the cytotoxic responses of these T-cells demonstrated selective reactivity against an epitope in peptide 123 presented by HLA DR12 DRB1 1201. Thus, these cytotoxic T-cells were restricted by an HLA DR allele not shared by the patient. Strikingly this patient developed severe CMV retinitis which required prolonged treatment with both ganciclovir and foscarnet and left significant residua. We have also seen refractory CMV infections in other recipients of HLA disparate grafts that have been correlated with a similar inability of T-cells generated from the donor to recognize CMVpp65 in the context of a shared allele. The frequency with which this failure of immunodominant T-cells to recognize immunogenic epitopes in the context of shared HLA alleles occurs in at least 33% of HLA disparate donor/recipient pairs studied in our series thus far. Thus, this may represent a significant obstacle to the effectiveness of functional reconstitution of virus-specific immunity following haplotype disparate transplants. It also may limit the effectiveness of adoptive cell therapies if not considered.

Figure 2.

IFN Gamma Release Assay-TC Sensitized with autologous DC loaded with CMV pp65 peptide pool

Approaches to Address the Constraints of Immunodominance

To address this limitation to effective adoptive immunotherapy in HLA-disparate recipients, our group has been exploring 2 new approaches which allow selective growth and/or selective administration of virus-specific T-cells of desired HLA restriction.

Use of Artificial Antigen Presenting Cells to Generate Virus-specific T-cells of Desired HLA restriction

The first approach employs the use of artificial antigen presenting cells (AAPCs) expressing a single HLA allele shared by donor and host for T-cell sensitization. This approach was initially suggested by the studies of LaTouche et al (43) who employed murine 3T3 cells transduced to express the human costimulatory molecules B71, LFA3 and ICAM1 together with beta 2 microglobulin and the heavy chain of the HLA A0201 allele as artificial antigen presenting cells. Their studies demonstrated that these artificial presenting cells when loaded or transduced to express immunogenic peptides derived from tumor antigens could elicit peptide-specific HLA A0201 restricted T-cell responses (43, 44). In a subsequent study these AAPCs, when transduced to express CMVpp65, were also found to stimulate the generation of T-cells again specific for the NLV peptide presented by HLA A0201 (45). Recently, our group has developed a panel of these AAPCs, each expressing a single prevalent HLA allele (46). Unlike the initial AAPCs expressing A0201, AAPCs expressing several other HLA alleles that were developed using the same technology failed to achieve stable high expression of the transduced HLA allele. To address this limitation, we have since modified the vectors to include the Kozak sequence (47) in the promoter which leads to markedly enhanced and strikingly stable long-term expression of each of these HLA allelic genes introduced into these cells. The panel we have developed now includes HLA A0201, A0101, A0301, A1101, A2402, B0701, B0801, HLA C0401. In addition we have recently developed AAPCs expressing 3 prevalent class II alleles using vectors that direct the stable expression of both the alpha and beta chains of these class II molecules. We have also evaluated the prevalence of the HLA alleles in the panel within our transplant population. Thus, among 500 recipients of 8/10–10/10 HLA matched marrow or peripheral blood stem cell T-cell depleted grafts, 80% inherited at least 1 of these alleles. Furthermore, among 100 patients for whom the only donor could be identified in the NMDP was a ≥ 3/6 HLA matched cord blood graft, 78 patients also inherited at least one of these alleles.

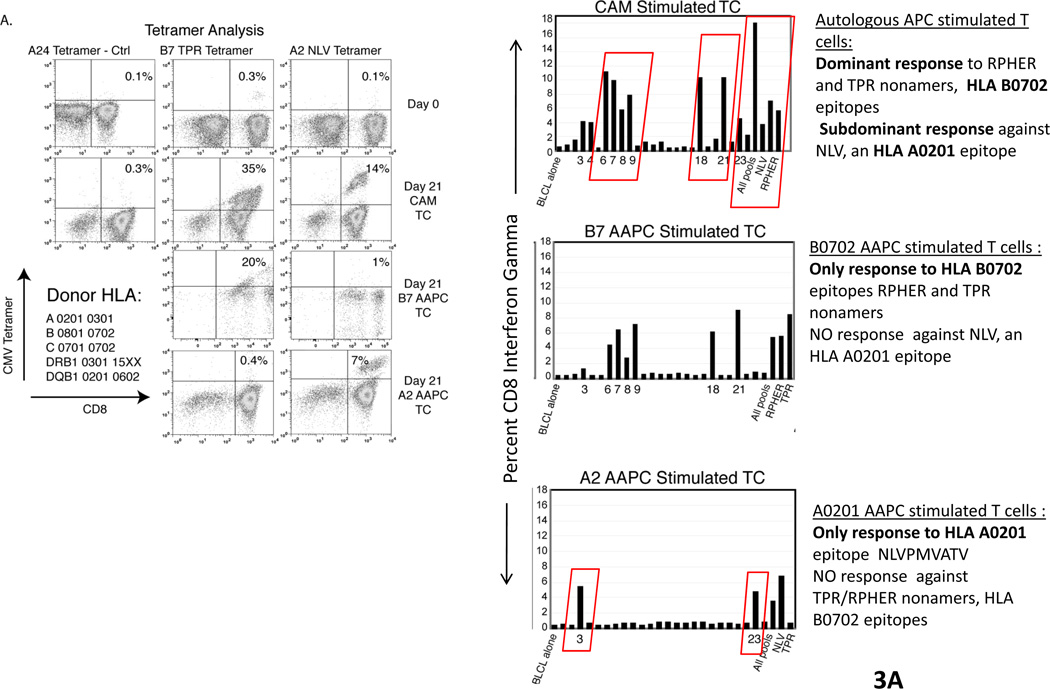

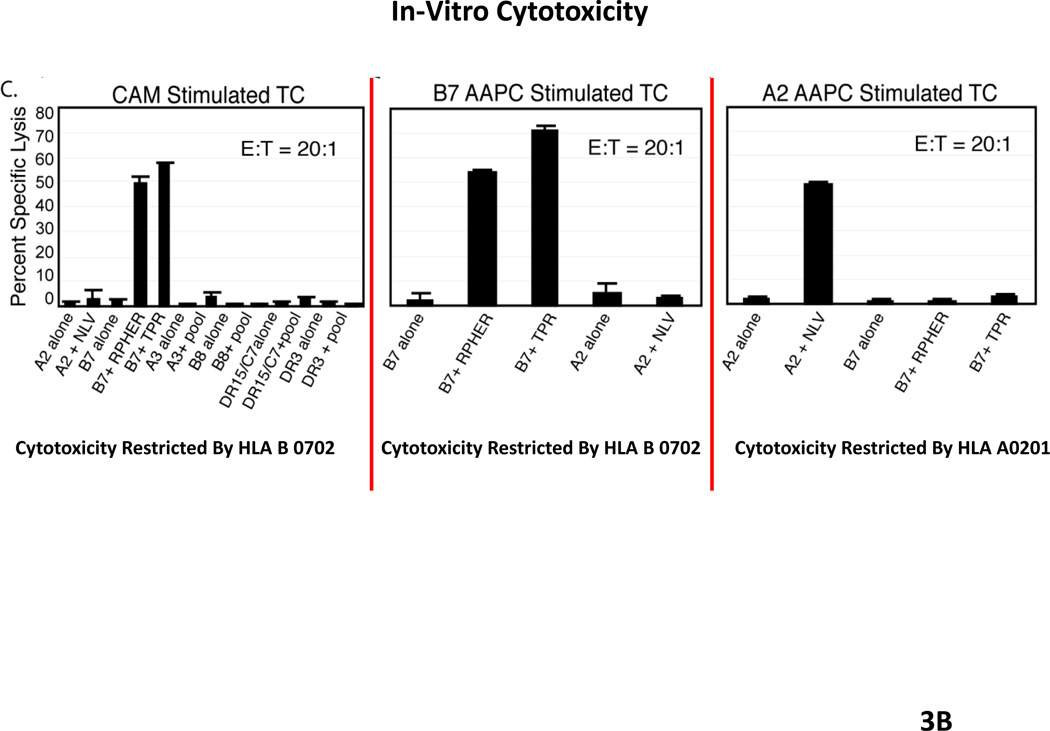

Each of these AAPCs has been shown to be effective in sensitizing and inducing the generation of CMV peptide specific T-cells restricted by the expressed HLA allele at frequencies that are comparable to or greater than those generated in response to autologous dendritic cells loaded with the peptides. We have also shown that these AAPCs can be used to generate CMVpp65-specific T-cells of desired HLA restriction (46). Thus, as shown in Figure 3, T-cells sensitized with autologous dendritic cells generate populations of T-cells that are exclusively specific for the RPH and TPR peptides, epitopes presented by HLA B0702. Similarly, AAPCs expressing HLA B0702 selectively sensitized T-cells against the TRP epitope presented by this allele. However, T-cells sensitized with with AAPCs expressing HLA A0201 selectively generate T-cells directed against the NLV peptide presented by this allele. These interferon gamma+ T-cells also exhibit appropriate HLA restricted cytotoxic activity directed against peptide loaded targets or infected targets expressing the encoded HLA A0201 allele. Indeed, by sensitizing T-cells with peptide pool loaded AAPCs expressing a shared HLA allele, we have been able to consistently generate T-cells specific for epitope presented by that allele, including epitopes that are subdominant and do not elicit responses in T-cells sensitized with peptide pool loaded autologous dendritic cells. This has proven to be a singular advantage. For example, as shown in Fig. 3, when T-cells are sensitized with autologous dendritic cells and the donor expresses HLA B0702, the immunodominant responses directed against CMVpp65 are almost invariably restricted by HLA B0702, irrespective of the other HLA alleles in the donor’s genotype (48). In contrast, using the artificial presenting cells, one is able to generate T-cells directed against epitopes presented by other inherited HLA alleles, such as HLA A0201 which exhibit the capacity to generate TH1 cytokines and to lyse both peptide loaded and CMV infected cells. Thus, this panel of AAPCs now provides a renewable source of antigen presenting cells that not only permits immediate sensitization of T-cells from a given donor in vitro but also permits generation of T-cells that are both virus specific and restricted by a desired HLA allele, namely, an HLA allele shared by the patient’s infected cells. We believe this strategy, which we are soon to introduce into clinical trials, may significantly enhance our capacity to provide functionally effective T-cells that are restricted by shared alleles for the treatment of viral infections in HLA haplotype disparate recipients.

Figure 3.

AAPC can be used to generate CMV-specific T cells of desired HLA Restriction

Use of HLA-Partially Matched Third Party-Derived Virus-Specific T-cells of Desired HLA Restriction for Adoptive Therapy

Another approach that is potentially immediately accessible for the treatment life threatening infections in HLA-haplotype disparate marrow graft recipients is the use of previously generated virus-specific T-cells of defined HLA restriction derived from HLA partially matched third party donors. This approach was initially pioneered by Haque et al (49) for the treatment of post transplant lymphoproliferative diseases induced by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV PTLD) in organ allograft recipients. The results of a subsequent multicenter trial employing such HLA-partially matched cells, selected exclusively on the basis of HLA allele sharing, suggested the potential of these cells to induce regressions EBV PTLD in up to 55% of individuals (50).

Over the course of the last 10 years, we have generated a large bank of GMP generated EBV-specific T-cells derived from marrow transplant donors that have been sensitized in vitro for periods of 28–35 days with irradiated, acyclovir treated autologous EBV transformed B cells. The T-cell lines generated over these extended periods of culture progressively depleted of alloreactive T-cells are lacking in alloreactivity and are EBV-specific. We first utilized these transplant donor derived T-cells to treat pathologically confirmed monoclonal EBV lymphomas arising in patients following T-cell depleted or unmodified marrow grafts (51, 52). Thus far, of the first 18 evaluable patients 10 have achieved a complete remission of disease. We have also used such T-cells to treat a small series of patients who have undergone organ allografts, and have thereby induced complete responses or durable partial responses (>2 yrs) in more than 75% of cases.

More recently, we have employed third party T-cells that are partially HLA matched derived separately consented donors in from this panel to treat patients who have developed monoclonal EBV lymphoma following either a cord blood transplant or a T-cell depleted graft (53). In these settings, the transplant donor was either EBV seronegative or unavailable for T-cell generation. Our initial experiences in 2 patients who developed EBV lymphomas in cord blood derived B cells following a double cord transplant have recently been reported (53), and have illustrated the potential of these third party T-cells, selected on the basis partial HLA matching and restriction of the EBV specific T-cells by an HLA allele shared by the recipient to induce durable regressions of disease. In these cases, the third party EBV-specific T-cells engraft and expand for periods of 7–14 days and thereafter fall to baseline levels. However, with repeated dosings, these cells can induce complete responses, as demonstrated both by resolution of PET avid and CT detectable tumor masses and lymph nodes, elimination of circulating EBV DNA and pathologic examination of involved tumors and nodes late after treatment. In these cases resolution of disease is usually observed between 14–21 days following initial infusion of a 3–6 week course of weekly infusions of the EBV specific T-cells.

One of the cases in our series uniquely demonstrates both the limitation to the therapeutic effectiveness of virus-specific T-cell therapy imposed by constraints of immunodominance and the potential utility of a panel of third party, partially HLA matched virus-specific of desired HLA restriction. This a patient received an HLA haplotype-disparate T-cell depleted transplant from a maternal donor as treatment for an EBV associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. In this case, EBV-specific T-cells were generated from the mother in anticipation that the patient would develop an EBV lymphoma in donor B-cells post transplantation. The patient did activate EBV and, furthermore, developed a monoclonal EBV+ B-cell lymphoma involving the gastric wall and mesenteric nodes. Repeated infusions of EBV-specific T-cells from the mother failed to clear this lymphoma or to alter its progression. Furthermore, despite additional treatment with Rituxan, EBV DNA persisted at high levels in the circulation. Biopsies of the EBV+ lymphoma demonstrated it to be of host rather than donor origin. This is unusual in that most EBV lymphomas developing following T-cell depleted grafts are in fact of donor type. Review of the HLA restriction of the maternal T-cells demonstrated that they were exclusively restricted by a single HLA allele, HLA A1101, which was not shared by the patient. Subsequent infusions of T-cells derived from an HLA-partially matched third party donor that were restricted by an HLA 2601 allele shared by the patient-origin lymphoma lead to complete resolution of disease as demonstrated by PET, by CT and by elimination of circulating EBV DNA.

Thus far in our studies, of the first 13 patients that have been treated with HLA partially matched EBV-specific T-cells of defined HLA restriction, 5 have achieved complete remissions and 3 have achieved sustained partial remissions of disease. An additional 2 patients that were treated for an EBV associated leiomyosarcoma have had long-term stabilization of disease. These promising early results suggest that repeated infusions of EBV specific T-cells derived from HLA partially matched donors that are appropriately restricted by an HLA allele shared by the underlying malignancy can induce durable regressions of disease.

In conclusion, our studies suggest that the increased and more prolonged susceptibility to CMV and EBV infections following HLA disparate T-cell depleted HSCT may in a significant proportion of cases reflect the incapacity of donor-derived immunodominant virus-specific T-cells that are restricted by HLA alleles to recognize infected cells of the host. To address this limitation we have developed a panel of AAPCs, each expressing a single prevalent HLA allele, together with critical human costimulatory molecules. We have also shown that these AAPCs when loaded with immunogenic peptides or transduced to express an immunogenic viral or tumor associated protein can process and present epitopes and elicit peptide specific cytotoxic T-cells. This panel constitutes an immediately accessible and renewable source of antigen presenting cells permitting immediate generation of virus-specific T-cells of desired HLA restrictions for adoptive prevention and or treatment of life threatening CMV and EBV infections in HLA haplotype matched transplant recipients. Preliminary results from our clinical trial also indicate that repeated infusions of HLA partially matched virus specific T-cells derived from third party donor that are appropriately restricted by HLA alleles expressed by infected cells of the host can transiently expand and persist for periods of 7–14 days following adoptive transfer and can induce durable regressions of EBV lymphomas following organ and hematopoietic grafts without risk of GVHD or organ allograft rejection. In the future, panels of HLA typed virus-specific T-cells of defined HLA restriction may provide an immediately accessible treatment option for life threatening viral infections complicating allogeneic hematopoietic cell and organ transplants and may significantly reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with such infections in recipients of HLA haplotype disparate hematopoietic cell transplants.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Supported in part by grants from the NIH, NCI CA23766, NCI CA59350, The Major Family Fund For Cancer Research, Laura Rosenberg Foundation, Julien Collot Foundation, Inc, The Aubrey Fund for Pediatric Cancer Research and The Max Cure Fund for Pediatric Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors do not have any financial or personal relationships with people or organizations that could inappropriately influence the content of this article.

References

Top 10 references indicated with *

- 1.Reisner Y, Kapoor N, Kirkpatrick D, Pollack MS, Dupont B, Good RA, O’Reilly RJ. Transplantation for acute leukaemia with HLA-A and B nonidentical parental marrow cells fractionated with soybean agglutinin and sheep red blood cells. Lancet. 1981;2:327–331. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reisner Y, Kapoor N, Kirkpatrick D, Pollack MS, Cunningham-Rundles S, Dupont B, et al. Transplantation for severe combined immunodeficiency with HLA-A,B,D,DR incompatible parental marrow cells fractionated by soybean agglutinin and sheep red blood cells. Blood. 1983;61:341–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Reilly RJ, Brochstein J, Collins N, Keever C, Kapoor N, Kirkpatrick D, et al. Evaluation of HLA-haplotype disparate parental marrow grafts depleted of T lymphocytes by differential agglutination with a soybean lectin and E-rosette depletion for the treatment of severe combined immunodeficiency. Vox Sang. 1986;51(Suppl 2):81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1986.tb02013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckley RH, Schiff SE, Schiff RI, Markert L, Williams LW, Roberts JL, et al. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for the treatment of severe combined immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:508–516. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902183400703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedrich W, Goldmann SF, Ebell W, Blutters-Sawatzki R, Gaedicke G, Raghavachar A, et al. Severe combined immunodeficiency: treatment by bone marrow transplantation in 15 infants using HLA-haploidentical donors. Eur J Pediatr. 1985;144:125–130. doi: 10.1007/BF00451897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowan MJ, Wara DW, Weintrub PS, Pabst H, Ammann AJ. Haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for severe combined immunodeficiency disease using soybean agglutinin-negative, T-depleted marrow cells. J Clin Immunol. 1985;5:370–376. doi: 10.1007/BF00915333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kernan NA, Flomenberg N, Dupont B, O'Reilly RJ. Graft rejection in recipients of T-cell-depleted HLA-nonidentical marrow transplants for leukemia. Identification of host-derived antidonor allocytotoxic T lymphocytes. Transplantation. 1987;43:842–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bordignon C, Keever CA, Small TN, Flomenberg N, Dupont B, O'Reilly RJ, et al. Graft failure after T-cell-depleted human leukocyte antigen identical marrow transplants for leukemia: II. In vitro analyses of host effector mechanisms. Blood. 1989;74:2237–2243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kernan NA, Bordignon C, Heller G, Cunningham I, Castro-Malaspina H, Shank B, et al. Graft failure after T-cell-depleted human leukocyte antigen identical marrow transplants for leukemia: I. Analysis of risk factors and results of secondary transplants. Blood. 1989;74:2227–2236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green A, Clarke E, Hunt L, Canterbury A, Lankester A, Hale G, et al. Children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who receive T-cell-depleted HLA mismatched marrow allografts from unrelated donors have an increased incidence of primary graft failure but a similar overall transplant outcome. Blood. 1999;94:2236–2246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young JW, Papadopoulos EB, Cunningham I, Castro-Malaspina H, Flomenberg N, Carabasi MH, et al. T-cell-depleted allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in adults with acute nonlymphocytic leukemia in first remission. Blood. 1992;79:3380–3387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papadopoulos EB, Carabasi MH, Castro-Malaspina H, Childs BH, Mackinnon S, Boulad F, et al. T-cell-depleted allogeneic bone marrow transplantation as postremission therapy for acute myelogenous leukemia: freedom from relapse in the absence of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1998;91:1083–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackinnon S, Barnett L, Bourhis JH, Black P, Heller G, O'Reilly RJ. Myeloid and lymphoid chimerism after T-cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation: evaluation of conditioning regimens using the polymerase chain reaction to amplify human minisatellite regions of genomic DNA. Blood. 1992;80:3235–3241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bachar-Lustig E, Rachamim N, Li HW, Lan F, Reisner Y. Megadose of T cell-depleted bone marrow overcomes MHC barriers in sublethally irradiated mice. Nat Med. 1995;1:1268–1273. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aversa F, Terenzi A, Tabilio A, Falzetti F, Carotti A, Ballanti S, et al. Full haplotype-mismatched hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a phase II study in patients with acute leukemia at high risk of relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3447–3454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klingebiel T, Cornish J, Labopin M, Locatelli F, Darbyshire P, Handgretinger R, et al. Results and factors influencing outcome after fully haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with very high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: impact of center size: an analysis on behalf of the Acute Leukemia and Pediatric Disease Working Parties of the European Blood and Marrow Transplant group. Blood. 2010;115:3437–3446. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-207001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakubowski AA, Small TN, Young JW, Kernan NA, Castro-Malaspina H, Hsu KC, et al. T cell depleted stem-cell transplantation for adults with hematologic malignancies: sustained engraftment of HLA-matched related donor grafts without the use of antithymocyte globulin. Blood. 2007;110:4552–4559. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soiffer RJ, Fairclough D, Robertson M, Alyea E, Anderson K, Freedman A, et al. CD6-depleted allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute leukemia in first complete remission. Blood. 1997;89:3039–3047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castro-Malaspina H, Jabubowski AA, Papadopoulos EB, Boulad F, Young JW, Kernan NA, et al. Transplantation in remission improves the disease-free survival of patients with advanced myelodysplastic syndromes treated with myeloablative T cell-depleted stem cell transplants from HLA-identical siblings. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:458–468. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucas KG, Small TN, Heller G, Dupont B, O'Reilly RJ. The development of cellular immunity to Epstein-Barr virus after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1996;87:2594–2603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tosato G, Steinberg AD, Yarchoan R, Heilman CA, Pike SE, De Seau V, et al. Abnormally elevated frequency of Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells in the blood of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:1789–1795. doi: 10.1172/JCI111388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao QY, Ogan P, Rowe M, Wood M, Rickinson AB. Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells persist in the circulation of acyclovir-treated virus carriers. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:67–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan LC, Gudgeon N, Annels NE, Hansasuta P, O'Callaghan CA, Rowland-Jones S, et al. A re-evaluation of the frequency of CD8+ T cells specific for EBV in healthy virus carriers. J Immunol. 1999;162:1827–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhaduri-McIntosh S, Rotenberg MJ, Gardner B, Robert M, Miller G. Repertoire and frequency of immune cells reactive to Epstein-Barr virus-derived autologous lymphoblastoid cell lines. Blood. 2008;111:1334–1343. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almyroudis NG, Jakubowski A, Jaffe D, Sepkowitz K, Pamer E, O'Reilly RJ, et al. Predictors for persistent cytomegalovirus reactivation after T-cell-depleted allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2007;9:286–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2007.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boeckh M, Leisenring W, Riddell SR, Bowden RA, Huang ML, Myerson D, et al. Late cytomegalovirus disease and mortality in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants: importance of viral load and T-cell immunity. Blood. 2003;101:407–414. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ljungman P. Immune reconstitution and viral infections after stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21(Suppl 2):S72–S74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broers AE, van Der Holt R, van Esser JW, Gratama JW, Henzen-Logmans S, Kuenen-Boumeester V, et al. Increased transplant-related morbidity and mortality in CMV-seropositive patients despite highly effective prevention of CMV disease after allogeneic T-cell-depleted stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2000;95:2240–2245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suparno C, Milligan DW, Moss PA, Mautner V. Adenovirus infections in stem cell transplant recipients: recent developments in understanding of pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:873–885. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001628176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chakrabarti S, Milligan DW, Brown J, Osman H, Vipond IB, Pamphilon DH, et al. Influence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) sero-positivity on CMV infection, lymphocyte recovery and non-CMV infections following T-cell-depleted allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a comparison between two T-cell depletion regimens. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:197–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Burik JA, Carter SL, Freifeld AG, High KP, Godder KT, Papanicolaou GA, et al. Higher risk of cytomegalovirus and aspergillus infections in recipients of T cell-depleted unrelated bone marrow: analysis of infectious complications in patients treated with T cell depletion versus immunosuppressive therapy to prevent graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1487–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Small TN, Avigan D, Dupont B, Smith K, Black P, Heller G, et al. Immune reconstitution following T-cell depleted bone marrow transplantation: effect of age and posttransplant graft rejection prophylaxis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1997;3:65–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Small TN, Papadopoulos EB, Boulad F, Black P, Castro-Malaspina H, Childs BH, et al. Comparison of immune reconstitution after unrelated and related T-cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation: effect of patient age and donor leukocyte infusions. Blood. 1999;93:467–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keever-Taylor CA, Wagner JE, Kernan NA, Small TN, Carter SL, Thompson JS, et al. Comparison of immune recovery in recipients of unmanipulated vs T-cell-depleted grafts from unrelated donors in a multicenter randomized phase II–III trial (T-cell depletion trial) Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:587–589. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Reilly RJ, Doubrovina E, Trivedi D, Hasan A, Kollen W, Koehne G. Adoptive transfer of antigen-specific T-cells of donor type for immunotherapy of viral infections following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplants. Immunol Res. 2007;38:237–250. doi: 10.1007/s12026-007-0059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koehne G, Doubrovina E, Hasan A, Barker J, Castro-Malaspina HR, Perales M, et al. A Phase I Dose Escalation Trial of Donor T Cells Sensitized with Pentadecapeptides of the CMV-pp65 Protein for the Treatment of CMV Infections Following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplants. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2009;114:2262. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trivedi D, Williams RY, O'Reilly RJ, Koehne G. Generation of CMV-specific T lymphocytes using protein-spanning pools of pp65-derived overlapping pentadecapeptides for adoptive immunotherapy. Blood. 2005;105:2793–2801. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Callan MF, Fazou C, Yang H, Rostron T, Poon K, Hatton C, et al. CD8(+) T-cell selection, function, and death in the primary immune response in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1251–1261. doi: 10.1172/JCI10590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hislop AD, Annels NE, Gudgeon NH, Leese AM, Rickinson AB. Epitope-specific evolution of human CD8(+) T cell responses from primary to persistent phases of Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Exp Med. 2002;195:893–905. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan N, Best D, Bruton R, Nayak L, Rickinson AB, Moss PA. T cell recognition patterns of immunodominant cytomegalovirus antigens in primary and persistent infection. J Immunol. 2007;178:4455–4465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Price DA, Brenchley JM, Ruff LE, Betts MR, Hill BJ, Roederer M, et al. Avidity for antigen shapes clonal dominance in CD8+ T cell populations specific for persistent DNA viruses. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1349–1361. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewin SR, Heller G, Zhang L, Rodrigues E, Skulsky E, van den Brink MR, et al. Direct evidence for new T-cell generation by patients after either T-cell-depleted or unmodified allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantations. Blood. 2002;100:2235–2242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Latouche JB, Sadelain M. Induction of human cytotoxic T lymphocytes by artificial antigen-presenting cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:405–409. doi: 10.1038/74455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dupont J, Latouche JB, Ma C, Sadelain M. Artificial antigen-presenting cells transduced with telomerase efficiently expand epitope-specific, human leukocyte antigen-restricted cytotoxic T cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5417–5427. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Papanicolaou GA, Latouche JB, Tan C, Dupont J, Stiles J, Pamer EG, et al. Rapid expansion of cytomegalovirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by artificial antigen-presenting cells expressing a single HLA allele. Blood. 2003;102:2498–2505. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hasan AN, Kollen WJ, Trivedi D, Selvakumar A, Dupont B, Sadelain M, et al. A panel of artificial APCs expressing prevalent HLA alleles permits generation of cytotoxic T cells specific for both dominant and subdominant viral epitopes for adoptive therapy. J Immunol. 2009;183:2837–2850. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kozak M. At least six nucleotides preceding the AUG initiator codon enhance translation in mammalian cells. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:947–950. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lacey SF, Villacres MC, La Rosa C, Wang Z, Longmate J, Martinez J, et al. Relative dominance of HLA-B*07 restricted CD8+ T-lymphocyte immune responses to human cytomegalovirus pp65 in persons sharing HLA-A*02 and HLA-B*07 alleles. Hum Immunol. 2003;64:440–452. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(03)00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haque T, Wilkie GM, Taylor C, Amlot PL, Murad P, Iley A, et al. Treatment of Epstein-Barr-virus-positive post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease with partly HLA-matched allogeneic cytotoxic T cells. Lancet. 2002;360:436–442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09672-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haque T, Wilkie GM, Jones MM, Higgins CD, Urquhart G, Wingate P, et al. Allogeneic cytotoxic T-cell therapy for EBV-positive posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease: results of a phase 2 multicenter clinical trial. Blood. 2007;110:1123–1131. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-063008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Papadopoulos EB, Ladanyi M, Emanuel D, Mackinnon S, Boulad F, Carabasi MH, et al. Infusions of donor leukocytes to treat Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1185–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404283301703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Reilly RJ, Small TN, Papadopoulos E, Lucas K, Lacerda J, Koulova L. Biology and adoptive cell therapy of Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders in recipients of marrow allografts. Immunol Rev. 1997;157:195–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barker JN, Doubrovina E, Sauter C, Jaroscak JJ, Perales MA, Doubrovin M, et al. Successful treatment of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated post-transplant lymphoma after cord blood transplant using third-party EBV-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]