Abstract

Herein we have explored two practical aspects of cryopreserving cultured mammalian cells during routine laboratory maintenance. First, we have examined the possibility of using a serum-free, hence more affordable, cryopreservative. Using five mammalian lines (Crandell Feline Kidney, MCF7, A72, WI 38 and NB324K), we found that the serum-free alternative preserves nearly as efficiently as the serum-containing preservatives. Second, we compared cryostorage of those cells in suspended versus a pellet form using both aforementioned cryopreservatives. Under our conditions, cells were in general recovered equally well in a suspended versus a pellet form.

Keywords: Cryopreservation; Cells, Cultured; Culture Media, Serum-Free

Introduction

The primary causes of cell death during cryopreservation appear to be formation of both ice crystals and osmotic gradients across the cell membrane (1-5). As such, cryopreservatives have been employed to retain viability during the freezing and thawing processes. Although numerous agents have been observed to promote cell viability during the freezing process (6), historically, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and glycerol have been used as preservatives for storing cells in a frozen state (1-2, 4, 6). During routine maintenance in many cell biology, virology, and molecular biology laboratories, mammalian cell lines are commonly stored in fetal bovine serum (FBS) plus 10% DMSO or growth medium containing serum plus 10%DMSO. Herein we have explored two practical aspects of cryopreserving cultured mammalian cells during routine laboratory maintenance. First, we have examined the possibility of using a serum-free, hence more affordable, cryopreservative. Lim et al. (7) have preserved bovine oocytes for 2-3 weeks in a serum-free PBS/DMSO cryopreservative, and Hubel et al. have employed a PBS/DMSO cryopreservative for short term cryo-studies of B lymphoblasts (8). We hypothesized that phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% DMSO would effectively preserve a variety of mammalian cell lines. To test this, we compared recovery of five cell lines after 30 days storage in either FBS+10%DMSO, RPMI1640+10%DMSO, or PBS+10%DMSO.

Second, we compared cryostorage of those same cells in suspended versus a pellet form in both aforementioned cryopreservatives. It has been reported that cell to cell contact influences survival during cryo-storage (9-11). In particular, membrane integrity of monolayered Chinese Hamster fibroblasts cells was more resistant to intracellular ice formation than that of non-monolayered controls (9, 10). While we do not expect the cells packed in a pellet to be gap- or tight-junctioned, we predicted that the packing of cells into a pellet would influence both the rate and extent of of intracellular ice formation, promoting cell survival. In addition, we also predicted that that the damage caused by ion partitioning (occurring during formation of the H2O crystal lattice) would be mitigated if cells were tightly packed in a pellet that excluded buffer. To test these predictions, we compared five mammalian cell lines, cryopreserved as either a pellet or a suspension, in each of the three cryopreservatives.

Materials and Methods

Figure 1 depicts the basic experiment carried out on each of the cell lines. This experiment was repeated three times for each cell line. In conducting this basic experiment, NB324K, A72, Crandell Feline kidney, MCF-7, and WI 38 cells were grown to 70%-90% confluency in 25cm2 tissue culture dishes in RPMI1640 (SIGMA, Sigma – St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 10% FBS (SIGMA, Sigma – St. Louis, MO, USA), in the absence of antibiotics. They were detached with trypsin/EDTA (SIGMA, St. Louis, MO, USA), the trypsin solution removed via centrifugation in a 15ml polypropylene conical tube (VWR International, West Chester, PA, USA), and then resuspended in 1 ml of fetal bovine serum (FBS), phosphate buffered saline (PBS), or RPMI1640 containing 10% dimethyl-sulfoxide (DMSO-SIGMA, St. Louis, MO, USA). Cells cryo-stored in a suspended state were immediately placed at -80ºC in a foam freezer box (18x18x9cm, with wall thickness of 5cm) packed with paper towels. Those cryo-stored in a pellet state were first spun for 5 minutes at 200xg. Cells were thawed 30-90 days later by placing the 15ml polypropylene conical tubes in a 37ºC water bath, and then spun at 200xg for 5 minutes. Cryopreservative was drained and residual solution removed with sterile transfer pipet and cells resuspended in 4mls fresh growth medium (above) followed by seeding into 25cm2 flasks.

Fig. 1. Cells were grown to 50-100% confluency in a 25cm2 flask.

They were next trypsinized, and upon detachment, 3ml of growth medium were added. Cells were then split equally into three 15ml conical polycentrifuge tubes, followed by centrifugation and removal of trypsin solution. Each pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of the idicated cryopreservative (each with 10%DMSO: FBS=fetal bovine serum, PBS=phosphate-buffered saline, and RPMI = RPMI1640 with bicarbonate). One half of the cells from each treatment were removed to a new tube and placed in centrifuge to generate a pellet. Pelleted and suspended cells were then inserted into a foam box containing paper towels and placed in a -80°C freezer.

Cell viability was measured using attachment and subsequent ‘spreading’ as a readout. Live cells were easily identified by the conversion from a spherical morphology in suspension to a ‘spread’ morphology characteristic for each individual cell line. Validation of this scoring method was carried out by monitoring cells post attachment. In all treatments for all cell lines, attached and spread cells proved viable by dividing themselves. This was ascertained by monitoring doubling time over several days. A72 and WI 38 were observed to double in confluency (substratum coverage) after 1-2 days, and, being at lower densities, attached NB324K, CRFK, and MCF-7 cells were located within hand-marked circular fields and observed to double within 1-3 days. This scoring method was used instead of dye exclusion because of the possibility that, during freezing and thawing, cells might sustain lethal damage to internal membranes but not external membranes; such cells would exclude dye and be scored as viable when in fact they were dead. Within 18-24 hours after seeding, flasks were rocked briefly to resuspend dead cells. Relative cell recovery (viability) for each treatment was then estimated by determining the average number (5 replicate windows) of attached and spread cells in a window at 100x.

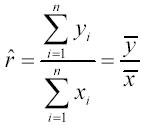

We evaluated the resulting data with two approaches. Firstly, we compared the relative performance of PBS and RPMI treatment to that of the FBS treatment by calculating, for each replication, the ratio of recovered cells in either the PBS or the RPMI1640 treatment to that in the FBS treatment. The estimator of the population ratio r is

with the variance of the ration estimator being calculated by

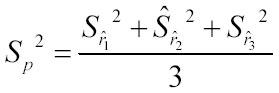

The individual ratios for each rep were then averaged to obtain a mean ratio for the three reps, and the accompanying pooled standard error, Sp, was calculated for three replications and five observations per replication

and pooled standard error

These ratios were calculated for cells cryo-stored in both the suspended and the pellet state, and the two states compared using a t-test. These results are presented in Table 1. Secondly, for each cell line we calculated the weighted mean and pooled standard deviation of cells recovered from each of the three repetitions for each cryopreservative, in either the suspended or the pellet state. For each cell line we then compared recovery in the three cryopreservatives using analysis of variance (ANOVA). If ANOVA indicated a significant difference in means, Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) statistic was calculated. LSD is a comparison criterion used to determine where differences in means occur. We also compared recovery in each cryopreservative in the suspended state to that in the pellet state using the standard t-test. These results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1. Comparison of cell recovery in phosphate-buffered saline or RPMI1640 based cryopreservative with recovery after storage in fetal bovine serum based cryopreservative.

| Cell Line | PBS/FBS suspended | PBS/FBS pellet | t-test | RPMI/FBS suspended | RPMI/FBS pellet | t-test |

| Crandell Feline Kidney | 0.62 sp =0.25 | 0.79 sp =0.35 | t=1.53 P=0.137 |

0.75 sp = 0.38 | 0.49 sp =0.21 | t=2.32 P=0.028 ** |

| MCF7 | 0.84 sp =0.34 | 0.90 sp =0.38 | t=0.46 P=0.652 |

0.92 sp =0.29 | 1.25 sp =0.85 | t=1.42 P=0.166 |

| A72 | 0.79 sp =0.15 | 0.76 sp =0.13 | t=0.58 P=0.563 |

0.87 sp =0.14 | 0.67 sp =0.09 | t=4.65 P=0.000 ** |

| NB324K | 0.58 sp =0.12 | 0.75 sp =0.21 | t=2.72 P=0.011 * |

0.50 sp =0.07 | 0.64 sp =0.09 | t=3.88 P=0.001 ** |

| WI 38 | 0.65 sp =0.10 | 0.62 sp =0.22 | t=0.48 P=0.634 |

0.87 sp =0.13 | 0.61 sp =0.18 | t=4.54 P=0.000** |

| Storage was carried out in either a suspended or a pellet state. Shown is a weighted mean and pooled standard error of the ratio of recovered cells in PBS/10%DMSO or RPMI1640/10%DMSO treatment to the same in accompanying FBS/10%DMSO treatment. Recovery was scored by counting five windows at 100x and then averaging for each rep. The weighted mean was calculated based on data from three repetitions for all treatments with all lines except for the RPMI/FBS ratio of NB324K, which is the average of two repetitions. sp is the pooled standard error of the replications. The t-tests are two tailed. *significant at the 0.05 level. **significant at the 0.01 level. | ||||||

Table 2. The weighted mean of three reps for each treatment in each state.

| Treatment | Suspension | Pellet | t-test suspension vs pellet |

| FBS/10%DMSO(1) |

CRFK 66

sP

=38

MCF7 12 sP = 7 A72 234 sP =69 NB324K 83 sP =26 WI 38 29 sP =9 |

CRFK 89

sP

=54

MCF7 8 sP = 4 A72 191 sP =58 NB324K 76 sP =22 WI 38 20 sP = 4 |

t=1.35 p=0.188 t=1.92 p=0.065 t=1.85 p=0.075 t=0.79 p=0.433 t=3.544 p=0.001** |

| PBS/10%DMSO(2) |

CRFK 40

sP

=11

MCF7 7 sP = 2 A72 190 sP =49 NB324K 50 sP =31 WI 38 16 sP = 5 |

CRFK 75

sP

=16

MCF7 8 sP = 3 A72 160 sP =37 NB324K 72 sP =26 WI 38 12 sP = 8 |

t=6.98 p=0.000** t=1.07 p=0.292 t=1.89 p=0.069 t=2.10 p=0.044* t=1.64 p=0.112 |

| RPMI1640/10%DMSO(3) |

CRFK 69

sP

=73

MCF7 10 sP = 4 A72 213 sP =31 NB324K 65 sP =14 WI 38 25 sP = 6 |

CRFK 70

sP

=55

MCF7 10 sP = 5 A72 145 sP =29 NB324K 95 sP =19 WI 38 12 sP = 6 |

t=0.00 p=0.967 t=0.00 p=1.000 t=6.20 p=0.000 ** t=4.92 p=0.000 ** t=5.93 p=0.000 ** |

| ANOVA FBS vs PBS vs RPMI | CRFK F=1.66, P=0.202 MCF7 F=4.13, P=0.023, LSD=3.5* A72 F=2.68, P=0.080 NB324K F=6.70, P=0.003, LSD=18.2** WI 38 F=14.05, P=0.000, LSD=5.07** |

F=0.7, P=0.5 F=1.2, P=0.3 F=4.4, P=0.02, LSD=31.8* F=4.5, P=0.02, LSD=16.6 * F=8.28, P=0.001, LSD=4.58** |

|

| The mean is followed by sP , the pooled standard deviation of the three reps. The t-tests are two tailed with 28 degrees of freedom. Analysis of Variance: The critical F value = 3.22 for α =0.05 and 2, 42 degrees of freedom. LSD=Fisher’s least significant difference for α =0.05. The critical F value = 5.15 for α = 0.01 and 2, 42 degrees of freedom.*significant at the 0.05 level. **significant at the 0.01 level. | |||

Results

Crandell Feline Kidney (CRFK) cells were isolated from the kidney of a domestic cat (12-14).

Suspended: The mean ratio of suspended cells surviving in PBS or RPMI treatment to those surviving FBS treatment are shown in Table 1. According to the ratios, cells in the suspended state the PBS preservatives appear to perform somewhat less efficiently than the RPMI and the FBS treatments. However, the F statistic generated from the mean number of cells recovered from each treatment suggests that these differences are not likely to be real (Table 2).

Pellet: The mean ratio of pelleted cells surviving in PBS or RPMI treatment to those surviving FBS treatment are shown in Table 1. Both serum-free media perform somewhat less efficiently than the FBS preservative, with the RPMI1640 cryopreservative supporting recovery at 0.5x that of the FBS preservative in the pellet state. The F statistic generated from the means of each cryopreservative in the pellet state suggests that these differences in ratios can be attributed to a large sampling variance rather than real differences between the preservatives (Table 2).

Suspended vs. Pellet: A t-test comparing the ratios of RPMI/FBS in pellet vs. suspension indicates that there is significant difference between relative recovery of RPMI-preserved cells stored a suspended or a pellet state (pellet state were recovered at 0.65x relative to those in suspended state). While this suggests that CRFK cells were recovered less efficiently from the pellet state if stored in RPMI, t-tests on the mean cell number recovered from each state suggests that there is no significant difference between recovery of cells from the RPMI preservative in either state. The t-tests on mean cell number also suggest that CRFK were more effectively (1.8-fold) recovered from the PBS cryopreservative when stored in a pellet form (Table 2).

MCF7 (15) is a human mammary epithelial line derived from a metastatic site.

Suspended: The mean ratio of suspended cells surviving in PBS or RPMI treatment to those surviving FBS treatment are shown in Table 1. The observed serum-free to FBS ratios were all within 25% of 1, and the F statistic generated from the mean number of cells recovered from the three cryopreservatives shows a significant difference only between the PBS and the FBS cryopreservatives. The difference amounts to 0.58x cells recovered from recovered from PBS versus FBS cryopreservative.

Pellet: The mean ratio of pelleted cells surviving in PBS or RPMI treatment to those surviving FBS treatment are shown in Table 1. The ratios of cells recovered from serum-free to those from the FBS cryopreservative are within 25% of 1, with the RPMI preservative slightly outperforming the FBS preservative. However, the F statistic generated from the means of the cells recovered from the three cryopreservatives suggests that there is no significant difference between the cryopreservatives if MCF7 cells are stored in the pelleted state.

Suspended vs. Pellet: t-tests indicate that pelleting cells had no influence on the PBS/FBS or the RPMI/FBS ratios, suggesting that all of the cryopreservatives performed equally in either the suspended or pelleted state (Table 1). t-tests comparing means number of cells recovered from each cryopreservative in each state also indicates that the suspension state (suspended or pelleted) does not influence recovery of MCF7 cells (Table 2).

A72 cells were derived from a canine fibroma and have been utilized in studies of canine parvovirus infection (13-14, 16-17).

Suspended: The mean ratio of suspended cells surviving in serum-free treatment to those surviving FBS treatment are shown in Table 1. These ratios indicate that both serum-free preservatives supported somewhat less recovery than the FBS preservative (both within 20% of 1), but ANOVA with the means of the cells recovered from the three cryopreservatives suggests that there is no significant difference between the cryopreservatives with cells stored in the suspended state.

Pellet: The mean ratio of pelleted cells surviving in serum-free treatment to those surviving FBS treatment are shown in Table 1. Both serum-free preservatives supported somewhat less recovery than the FBS preservative, and the LSD statistic generated from the means of the cells recovered from the three cryopreservatives suggests that recovery from the RPMI preservative promotes recovery of pelleted A72 cells at 0.76x that of FBS preservative.

Suspended vs. Pellet: A t-test suggests that pelleting cells had no influence on the PBS/FBS ratio (Table 1), suggesting that the suspension state does not influence the relative recovery of cells in these two preservatives. A t-test also suggests that the RPMI/FBS recovery ratio was 0.8x in the pellet state vs. in the suspended state. t-tests comparing mean numbers of recovered cells for each each cryopreservative (in each state) suggest that the suspension state (suspended or pelleted) does not influence recovery of A72 cells stored in either PBS or FBS cryopreservatives, but that A72 in RPMI in the suspended state were recovered 1.47x more efficiently than those in pellet state (Table 2). These results indicate efficient recovery of A72 in serum free cryopreservatives from either the pelleted or the suspended state.

NB324K is an SV/40 transformed human kidney cell line (18-20).

Suspended: The mean ratio of cells surviving in the two serum-free treatments, PBS or RPMI based, to those surviving FBS treatment are shown in Table 1. Both serum-free cryopreservatives supported only half the recovery of the FBS preservative, but the LSD statistic on mean number of recovered cells suggests that only the difference between the PBS and FBS treatments is real (Table 2). This difference is 0.60x cells recovered from the PBS versus the FBS treatment.

Pellet: The mean ratio of cells surviving in serum-free treatment to those surviving FBS treatment are shown in Table 1. Ratios indicate somewhat lower recovery from the serum-free preservatives with cells stored in a pelleted state. However, the LSD statistic from mean number of NB324K cells recovered from the three cryopreservatives indicate that the RPMI treatment likely supported a 1.3x higher rate of recovery than either the PBS or the FBS preservatives (Table 2) when these cells were stored in a pellet state.

Suspended vs. Pellet: t-tests indicate that the ratio of recovered cells for PBS/FBS and RPMI/FBS is 1.3x higher with cells stored in the pellet state. Comparisons of the mean number of recovered cells (Table 2) reveals that cells stored in PBS preservative were recovered with 1.4x greater efficiency in the pellet state. Those in the RPMI preservative were recovered with 1.5x greater efficiency in the pellet state. These results indicate that the serum-free preservatives were slightly more effective at preserving pelleted NB324K cells (versus suspended cells) in a frozen state.

WI 38 is a human diploid fibroblast line with a finite life of 50+/-10 divisions (21-23), that has been utilized in production of poliovirus vaccine (22). These cells arose from a primary explant of human fetal lung tissue, the chromosomes are considered normal, and the cells have undergone no known transformation events.

Suspended: The mean ratio of suspended cells surviving in PBS or RPMI treatment to those surviving FBS treatment are shown in Table 1. According to the ratios, both serum free preservatives appear to perform somewhat less efficiently than the FBS treatment with cells in the suspended state. The F statistic generated from the mean number of cells recovered from each treatment suggests that the PBS treatment truly did not support recovery as well as did the FBS or RPMI-based preservatives.

Pellet: The mean ratio of pelleted cells surviving in PBS or RPMI treatment to those surviving FBS treatment are shown in Table 1. Both serum-free media perform approximately 0.60x less efficiently than the FBS preservative. The F statistic generated from the means of each cryopreservative in the pellet state suggests that these differences in ratios are real (Table 2).

Suspended vs. Pellet: A t-test indicates that there is a significant difference in the ratio of cells recovered from serum-free versus serum containing after storage in a pellet versus a suspended state (Table 1). Analysis of the mean number of recovered cells shows that for the FBS treatment, WI 38 cells stored in a pellet state were recovered at 0.67x relative to those in suspended state, and those from the RPMI cryopreservative in pellet state were recovered at 0.48x relative to those in suspended state (Table 2).

Discussion

Based upon the PBS/FBS and RPMI/FBS ratios, it appears that in most cases survival in the serum-free preservatives is somewhat lower than that in serum-containing conditions. The largest lowering observed was a halving of the recovery rate, which occurred in two cases: NB324K in RPMI1640 preservative in the suspended state and CRFK in RPMI preservative in the pellet state (see Table 2). In some cases, the serum-free preservatives performed somewhat better than the serum-containing counterpart. In general, we feel that the differences we observed are of no practical consequence when cryostoring cells during routine maintenance because typically millions of cells are frozen during these procedures. In laboratories that store large volumes of cultured cells, this ability to eliminate expensive serum from cryopreserving solutions may represent a significant cash savings. Collectively, the data also indicate that there are not large differences in recovery rate of cells stored in pellet versus suspended form. This suggests that packing the cells together did not influence damage due to ice crystal formation or osmotic stresses. We note, however, we were working with fairly low numbers of cells that produced pellets on the order of 0.1-0.5 mm3, and it is possible that the above predictions would not manifest themselves until the packing volume reached an as yet undetermined threshold.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in full by Nebraska’s Biomedical Research Infrastructure Network grant number # P20RR16469. We also thank our BRIN scholar Mr. Ethan Mann and our laboratory aid Mr. Scott Wewel for maintenance of cell cultures during the latter stages of these studies.

References

- Polge AS, Smith AU, Parks AS. Survival of spermatozoa after dehydration and vitrification at low temperature. Nature. 1949;164:666–666. doi: 10.1038/164666a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P. Cryobiology: The freezing of biological systems. Science. 1970;168:939–949. doi: 10.1126/science.168.3934.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P, Leibo SP, Chu EHY. A two-factor hypothesis of freezing injury. Exp Cell Res. 1971;72:345–355. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(72)90303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovelock JE, Bishop MH. Prevention of freezing damage to living cells by dimethyl-sulphoxide. Nature. 1959;183:1394–1395. doi: 10.1038/1831394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann J, Korber CH, Rau G, Hubel A, Cravalho EG. Redefining cooling rates in terms of ice front velocity and thermal gradient: first evidence of relevance to freezing injury of lymphocytes. Cryobiology. 1990;27:279–287. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(90)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelbe RJ, Mancuso MG. Identification of new cryoprotective agents for cultured mammalian cells. In Vitro. 1983;19:167–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02618055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JM, Ko JJ, Hwang WS, Chung HM, Niwa K. Development of in vitro matured oocytes after cryopreservation with different cryoprotectants. Theriogenology. 1999;51:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/S0093-691X(99)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel A, Cravalho EG, Nunner B, Korber C. Survival of directionaly solidified B-lymphoblasts under various crystal growth conditions. Cryobiology. 1992;29:183–198. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(92)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acker JP, McGann LE. Cell-cell contact affects membrane integrity after intracellular freezing. Cryobiology. 2000;40:54–63. doi: 10.1006/cryo.1999.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acker JP, Larese A, Yang H, Petrenko A, McGann LE. Intracellular ice formation is affected by cell interactions. Cryobiology. 1999;38:363–371. doi: 10.1006/cryo.1999.2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage WJ, Juss BK. Assembly of intercellular junctions in epithelial cell monolayers following exposure to cryoprotectants. Cryobiology. 2000;41:58–65. doi: 10.1006/cryo.2000.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandell RA, Fabricant CG, Nelson-Rees WA. Development, characterization, and viral susceptibility of a feline (Felis catus) renal cell line (CRFK). In Vitro. 1973;9:176–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02618435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer AL, Maxwell F, Corsini J, Maxwell IH. Species specificity for transduction of cultured cells by a recombinant LuIII rodent parvovirus genome encapsidated by canine parvovirus or feline panleukopenia virus. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1787–1792. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-8-1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer AL, Parrish CR, Maxwell IH. Tropic determinant for canine parvovirus and feline panleukopenia virus functions through the capsid protein VP2. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:925–928. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-4-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman BJ, Aggarwal BB, Hass PE, Figari IS, Palladino IA Jr., Shepard HM. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor-alpha: effects on proliferation of normal and transformed cells in vitro. Science. 1985;230:943–945. doi: 10.1126/science.3933111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binn LN, Marchwicki RH, Stephenson EH. Establishment of a canine cell line: derivation, characterization, and viral spectrum. Am J Vet Res. 1980;41:855–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish CR, Aquadro CF, Carmichael LE. Canine host range and a specific epitope map along with variant sequences in the capsid protein gene of canine parvovirus and related feline, mink, and raccoon parvoviruses. Virology. 1988;166:293–307. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90500-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shein HM, Enders JF. Multiplication and cytopathogenicity of simian vacuolating virus in cultures of human tissues. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1962;109:495–500. doi: 10.3181/00379727-109-27246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsini J, Maxwell F, Maxwell IH. Storage of various cell lines at -70C or -80C in multi-well plates while attached to the substratum. Biotechniques. 2002;33:1–3. doi: 10.2144/02331bm05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsini J, Maxwell IH, Maxwell F, Carlson JO. Expression of parvovirus LuIII NS1 from a Sindbis replicon for production of LuIII-luciferase transducing virus. Virus Res. 1996;46:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(96)01381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1961;25:585–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick L, Plotkin SA, Norton TW, Koprowski IH. Preparation of poliovirus vaccines in a human fetal diploid cell strain. Am J Hyg. 1962;75:240–258. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1965;37:614–636. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]