Abstract

Pet allergens are major causes for asthma and allergic rhinitis. Fel d 1 protein, a key pet allergen from domestic cat, can sensitize host and trigger asthma attack. In this study, we report that co-immunization with recombinant Fel d 1 protein (rFel d 1) plus plasmid DNA that contains Fe1 d 1 gene was effective in preventing and treating the natural Fel d 1 (nFel d 1) induced allergic airway inflammation in mice. A population of T regulatory cells (iTreg) exhibiting a CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ phenotype and expressing IL-10 and TGF-β was induced by this co-immunization strategy. Furthermore, after adoptive transfers of the iTreg cells, mice that were pre-sensitized and challenged with nFel d 1 exhibited less signs of allergic inflammation, AHR and a reduced allergic immune response. These data indicate that co-immunization with DNA and protein mixture vaccine may be an effective treatment for cat allergy.

Keywords: Fel d 1, airway inflammation, co-immunization, vaccine, T regulatory cell

Introduction

Allergic asthma is caused by hypersensitive immune disorder (type I hypersensitivity). Common allergens, such as house dust, pollen and animal dander,1 promote type 2 T cell responses to allergic rhinitis or asthma. Felis domesticus allergen 1 (Fel d 1), which is a dander protein primarily found in cat saliva and sebaceous glands,2,3 can elicit IgE responses in 95% of patients who are allergic to cat.4,5 The clinically symptoms of cat allergy range from mild rhinitis, conjunctivitis, allergic inflammation to even life-threatening asthmatic responses.

The most common treatment of allergic asthma includes avoidance of the allergen, pharmacotherapy and allergen-specific immunotherapy (allergen-SIT). However, each method has its drawbacks. Avoidance of allergens is often difficult and not always possible. Pharmacotherapy, such as bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory drugs, can only temporarily relieves allergic symptoms, but fails to have any effect on immunological disorder that results in allergy. Immunotherapy, such as desensitization with multiple s.c. injections, takes years to desensitize,6,7 thus making treatment difficult both for patients and for clinicians. Therefore, allergen tolerance needs to be induced with a more feasible and cost-effective SIT-treatment method.

Previously, we reported that a co-immunization vaccine is capable of alleviating allergy.8,9 The vaccine, consisting of allergen (Protein vaccine) and plasmid coding same allergen (DNA vaccine), was able to induce allergen specific tolerance following co-immunization. To explore the mechanism behind this tolerance, it was found that a unique subset of regulatory T cells (Treg) was induced by co-immunization.10 This subset of inducible Treg has a CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ phenotype and could suppress allergic response.9 As the protein and DNA combined vaccine is easy to immunize and induce an allergic specific tolerance, we are interested in its clinical potential on domestic asthma. In this report, we investigated whether the co-immunization vaccine of the major cat allergen Fel d 1 is effective to induce allergen tolerance and to treat allergy.

Results

Vaccine preparation

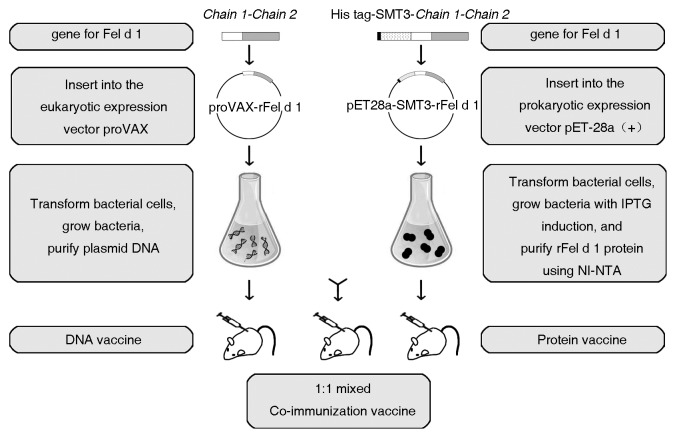

Fel d 1 is a 17-KD heterodimer containing two peptide chains linked by three Interchain disulphide bonds: chain 1 with 70 amino acids and chain 2 with 90–92 amino acids. In natural Fel d 1, two of these heterodimers form a tetramer with a molecular weight of 33–39-KD glycoprotein.2 To prepare Fel d 1 antigen and its corresponding gene (DNA) for co-immunization, rFel d 1 protein and the eukaryotic expression plasmid proVAX-rFel d 1 were generated and prepared.

Briefly, the plasmids pET28a-SMT3-rFel d 1 and proVAX-rFel d 1 expressing rFel d 1 were constructed by directly linking the C-terminal residue of chain 1 (Cys70) to the N-terminal residue of chain 2 (Val70) as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Figure S1, the plasmid pET28a-SMT3-rFel d 1 were expressed efficiently in Escherichia coli. (lane 3, Fig. S1B) and the rFel d 1 was purified (lane 6, Fig. S1B) and characterized by western blot (Fig. S1C). In addition, vector proVAX-rFel d 1 could also successfully express rFel d 1 antigen in mammalian cells, as had been shown by western blot analysis (Fig. S1D).

As indicated in Figure 1, mice were immunized with plasmid proVAX-rFel d 1 (DNA vaccine), rFel d 1 (protein vaccine) and the equal (1:1) mixture of the both (co-immunization vaccine).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of vaccine preparation. Vectors proVAX-rFel d 1 and pET28a-SMT3-rFel d 1 expressing rFel d 1 antigen were constructed as described in Materials and Methods. Vector proVAX-rFel d 1 was transformed in bacterial cells and plasmid DNA was purified and incorporated into a DNA vaccine. rFel d 1 was expressed in E.coli with IPTG induction, purified and used as a protein vaccine. Plasmid DNA was mixed 1:1 with the purified rFel d 1 to make co-immunization vaccine.

Prevention and treatment of nFel d 1-induced allergic airway inflammation in a mouse model by DNA/protein vaccine co-immunization

To address if co-immunization vaccine could alleviate the signs of allergic inflammation in the rFel d 1 allergic model, BALB/c mice were sensitized and challenged with rFel d 1. As data showed that co-immunization vaccine was able to prevent and to treat rFel d 1 airway inflammation (Figs. S2 and S3), we then examined the efficacy of co-immunization on airway inflammation induced by native Fel d 1 (nFel d 1).

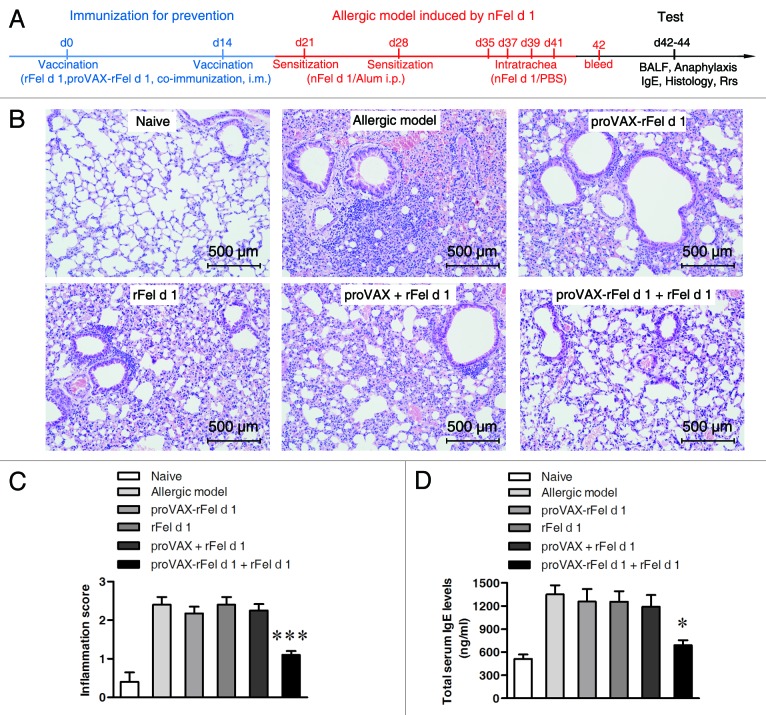

To test if co-immunization vaccine prevents allergic airway inflammation in the nFel d 1 allergic model, BALB/c mice were i.m. co-immunized twice with plasmid proVAX-rFel d 1 plus rFel d 1 vaccine. Single immunization with either proVAX-rFel d 1 or rFel d 1 alone, or mismatch immunizations with rFel d 1 plus proVAX vector were used as controls. These mice were then sensitized and challenged with nFel d 1 protein (Fig. 2A). Naïve mice neither vaccinated nor sensitized were used as negative controls. The allergic mice without any pre-vaccination were used as a positive control.

Figure 2. Lung inflammation and total serum IgE levels in mice inmmunized with different vaccines. (A) Schematic outline of the experiment. (B) Histological examination of lung tissues by H&E staining (n = 5). Magnification, × 200. (C) Lung inflammation was defined as the peribronchial inflammation score (n = 5). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM *** p < 0.001; significantly different from the allergic group. (D) Serum of individual mouse was collected after intratrachea with nFel d 1 (d42). Total serum IgE levels were measured using double-antibody sandwich ELISA technique (n = 6). * p < 0.05.

Airway inflammation was evaluated with H&E histology. The infiltration of inflammatory cells was inhibited in the co-immunization group comparing with the positive control groups and other vaccinated groups (Fig. 2B and C). Moreover, lower BAL cell numbers (Table 1) were observed in co-immunization group. Similarly, differential cell counts showed that, compared with allergic model groups the number of eosinophis was significantly reduced only in the DNA/protein co-vaccine group. Total serum IgE was also significantly suppressed in the co-immunization vaccine group (Fig. 2D).

Table 1. Characterization of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from mice immunized with different vaccines in a prevention experimental model.

| Groups | Total cells (X 103/ml) |

Eosinophis (X 103/ml) |

Basophils (X 103/ml) |

Monocytes (X 103/ml) |

Neutrophils (X 103/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve | 107.67 ± 32.39 | 8.61 ± 2.59 | 0.17 ± 0.29 | 1.62 ± 0.49 | 21.53 ± 6.48 |

| Allergic model | 241.33 ± 47.59 | 72.40 ± 14.28 | 0.96 ± 0.90 | 3.62 ± 0.71 | 48.27 ± 9.52 |

| proVAX-rFel d 1 | 220.33 ± 27.74 | 66.10 ± 8.32 | 0.97 ± 0.90 | 3.31 ± 0.42 | 44.07 ± 5.55 |

| rFel d 1 | 235.33 ± 32.25 | 70.60 ± 9.68 | 1.31 ± 1.46 | 3.53 ± 0.48 | 47.07 ± 6.45 |

| proVAX + rFel d 1 | 230.00 ± 26.85 | 69.00 ± 8.06 | 0.99 ± 0.87 | 3.45 ± 0.40 | 46.00 ± 5.37 |

| proVAX-rFel d 1 + rFel d 1 | 131.00 ± 35.79 * | 26.20 ± 7.16 *** | 0.81 ± 1.03 | 2.01 ± 0.40 * | 27.90 ± 5.51 * |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. ANOVA, co-immunization vaccine group vs. other vaccine group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005, *** p < 0.0005.

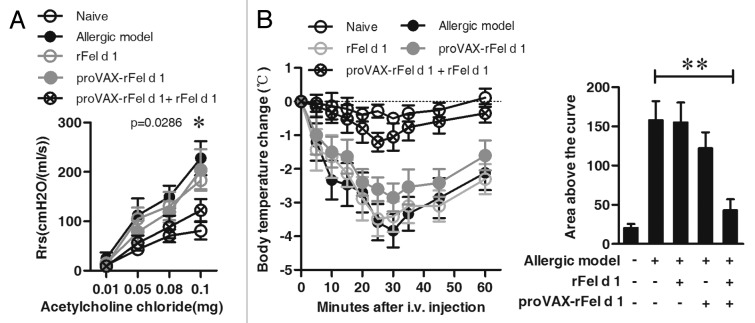

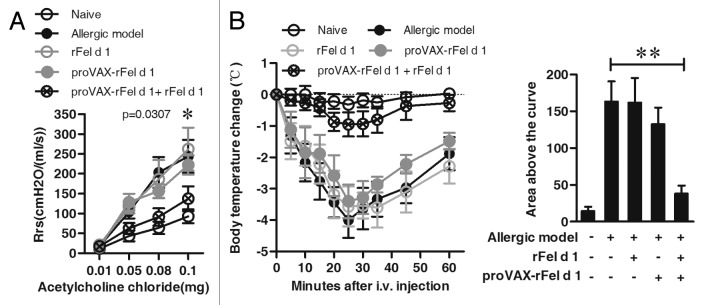

To determine whether the co-immunization ameliorates airway hyperreactivity (AHR), the dynamic respiratory resistance (Rrs) was measured in response to acetylcholine chloride at various doses. As shown in Figure 3A, values of Rrs were significantly higher in the allergic model group than in the naïve group in response to acetylcholine chloride. Co-immunization treatment significantly reduced the level of Rrs (co-immunization group vs. model group, p = 0.0307, i.v. acetylcholine chloride at 0.08mg, Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Prevention of AHR and acute systemic anaphylaxis by co-immunization strategy. (A) AHR was measured by the RC system in mice in response to the intra-jugular administration of acetylcholine chloride at various doses on the x-axis and expressed as Rrs on the y-axis. The allergic model was induced by nFel d 1 without vaccination (n = 6). (B) After vaccination and follow-up sensitization, 6 mice of each group were challenged i.v. with rFel d 1 and body temperature was measured at regular intervals. Changes in body temperature in degrees Celsius ± SD are shown on the left panel and mean area above the curves ± SD on the right panel (n = 6). Data shown are representative of three independent experiments with the same number of mice per group. A: * p < 0.05; B: ** p < 0.001.

The preventive efficacy of co-immunization was further examined by allergic anaphylaxis. Experimental mice (n = 6) were challenged with high-dose of rFel d 1 by i.v. injection, and body temperatures were monitored at regular intervals. As shown in Figure 3B, mice in allergic model group experienced anaphylaxis with severe drops in body temperature. Similarly, the sharp drops in body temperature were also observed in the proVAX-rFel d 1 alone or rFel d 1 vaccine alone group. However, co-immunization suppressed anaphylaxis with only mild temperature drops. When the changes in temperature were analyzed as the areas under the curve over 60 min, only the co-immunization with proVAX-rFel d 1 plus rFel d 1 revealed a significant suppression of anaphylaxis compared with the allergic mice (p < 0.001, Fig. 3B).

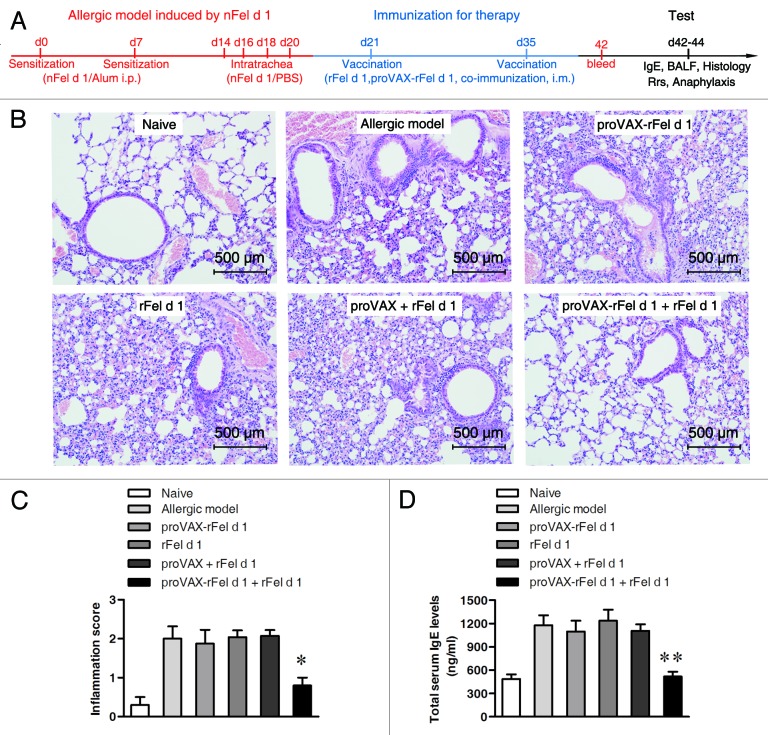

To further investigate whether the co-immunization vaccine could treat the established airway allergic inflammation, BALB/c mice were sensitized and challenged with nFel d 1 antigen, then randomly divided into several groups and immunized with different types of vaccines. Once again, naïve mice were negative control and the allergic mice without vaccination were positive control (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Therapeutic relief of nFel d 1-induced allergic symptoms in mice by co-immunization. (A) Schematic outline of the experiment. (B) Histological examination of lung tissues (n = 5) by H&E staining (d43). Magnification, × 200. (C) Lung inflammation was defined as the peribronchial inflammation score (n = 5). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM * p < 0.05; significantly different from the control group. (D) Serum of individual mouse was collected after vaccination (d42). Total serum IgE levels were measured using double-antibody sandwich ELISA technique (n = 6) and shown as mean total serum IgE levels ± SD, ** p < 0.005.

Among the various types of vaccine options, only the co-immunization group of proVAX-rFel d 1 plus rFel d 1 can significantly alleviate the symptoms in the established allergic model. As can be seen in Figures 4 and 5, compared with the model group, co-immunization vaccine resulted in diminishment of inflammatory cells infiltration in the lung tissue (Fig. 4B and C), a decrease in total serum IgE levels (Fig. 4D) and significant relief in the level of Rrs (i.v. acetylcholine chloride at 0.1mg, p = 0.0286, Fig. 5A). In addition, a mild drop in body temperature was observed in co-immunization group (Fig. 5B). BAL result (Table 2) showed that only DNA/protein co-vaccine group can significantly reduce the number of total BAL cells and eosinophils.

Figure 5. Reduction of AHR and inhibition of anaphylactic reaction by DNA/Protein co-vaccination. (A) AHR was measured by the RC system in mice in response to the intra-jugular administration of acetylcholine chloride at various doses on the x-axis and expressed as Rrs on the y-axis. The nFel d 1-induced allergic model without vaccination were regarded as positive control (n = 6). (B) Eight days after the second vaccination, 6 mice in each group were challenged i.v. with rFel d 1 and body temperature was measured at regular intervals. Changes in body temperature in degrees Celsius ± SD (n = 6) are shown on the left panel and mean area above the curves ± SD (n = 6) on the right panel. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments with the same number of mice per group. (A): * p < 0.05; (B): ** p < 0.001.

Table 2. Characterization of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from mice immunized with by different vaccines in a therapeutic experimental model.

| Groups | Total cells (X 103/ml) |

Eosinophis (X 103/ml) |

Basophils (X 103/ml) |

Monocytes (X 103/ml) |

Neutrophils (X 103/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve | 94.00 ± 31.00 | 8.27 ± 1.76 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 1.41 ± 0.47 | 18.80 ± 6.20 |

| Allergic model | 218.00 ± 32.08 | 65.40 ± 9.62 | 1.17 ± 0.76 | 3.27 ± 0.48 | 43.60 ± 6.42 |

| proVAX-rFel d 1 | 207.33 ± 30.09 | 62.20 ± 9.03 | 0.94 ± 0.92 | 3.11 ± 0.45 | 41.47 ± 6.02 |

| rFel d 1 | 222.67 ± 21.13 | 66.80 ± 6.34 | 1.28 ± 1.49 | 4.24 ± 1.56 | 44.53 ± 4.23 |

| proVAX + rFel d 1 | 209.67 ± 27.68 | 62.90 ± 8.30 | 0.93 ± 0.93 | 3.15 ± 0.42 | 41.93 ± 5.54 |

| proVAX-rFel d 1 + rFel d 1 | 123.33 ± 15.63 ** | 20.00 ± 5.33 *** | 0.50 ± 0.43 | 2.29 ± 0.59 | 24.67 ± 3.13 ** |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. ANOVA, co-immunization vaccine group vs. other vaccine group, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005, *** p < 0.0005.

Collectively, these results demonstrated that the co-immunization strategy had both preventive and therapeutic effects on nFel d 1-induced allergic airway inflammation in mice.

Functional CD4+CD25- Treg is induced by co-immunization vaccine

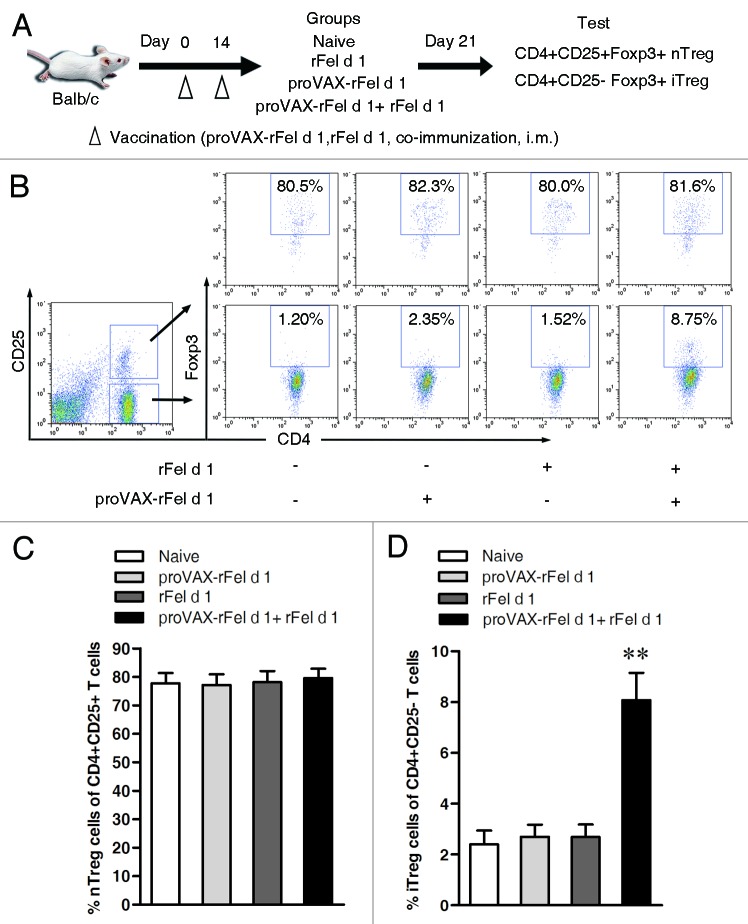

To address if previous prevention and treatment by co-immunization was due to tolerance induction, we tested regulatory T cells after immunization. Previous studies demonstrated that a subset of CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ phenotype Treg cells secreting IL-10 and TGF-β were induced by co-immunization with protein antigen plus cognate DNA vaccine.10,11 Therefore, here we tested Foxp3+ Tregs in CD4+CD25- population in co-immunized mice. BALB/c mice were immunized by different vaccines and then tested for iTregs. As shown in Figure 6, mice co-immunized with proVAX-rFel d 1 plus rFel d 1 had a higher level of CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ iTreg cells than other two groups that were treated either with proVAX-rFel d 1 alone or rFel d 1 alone, while the percentage of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ nTreg cells did not change in all other groups. Similarly, established allergic model mice showed the same trend that percentage of iTregs was increased after being vaccinated with DNA/protein co-vaccine, while percentage of nTregs was not changed (Fig. S4), indicating that nTreg cells are not involved in the beneficial effects. These data suggests CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ iTreg were efficiently induced by co-immunization.

Figure 6. Induction of CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ T regulatory cells in BALB/c mice by co-immunization with DNA and protein mixture (1:1) vaccine. (A) Schematic outline of the experiment. (B) Seven days after the second immunization, single splenocyte suspensions were prepared from mouse spleen and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ nTreg cells were analyzed by gating on the CD4+CD25+ T cells, and percentages of CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ iTreg cells were analyzed by gating on the CD4+CD25- T cells during FACS analysis. Naïve mice without vaccination were regarded as negative control. (C) Statistical analysis of percentages of nTreg cells (Left, n = 6) and iTreg cells (Right, n = 6). Compared with naïve group, mice treated with co-immunization strategy can induce CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ iTreg cells. Numbers in the outlined areas indicate percentage of cells. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments with the same number of mice per group. ** p < 0.005.

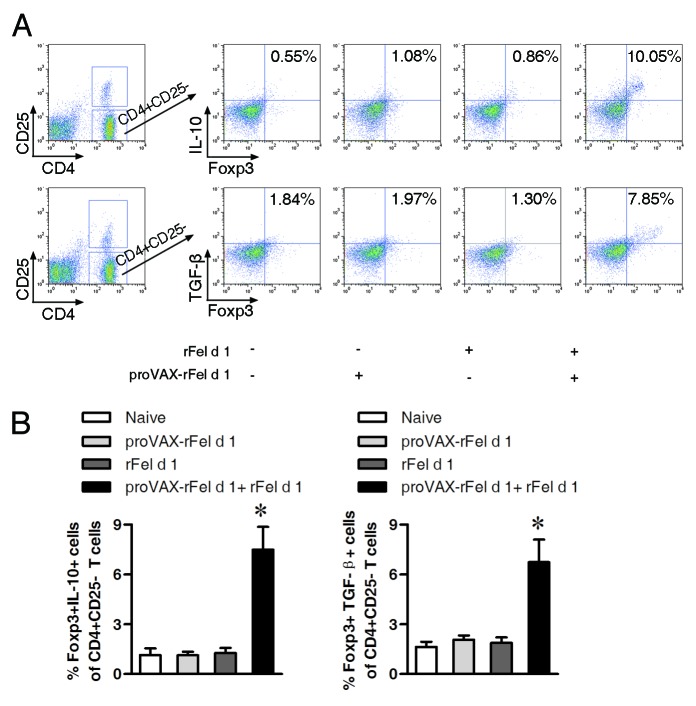

To further determine whether the iTreg cells induced by the co-immunization vaccine express certain types of well-documented markers associated with Treg cells (e.g., Foxp3, TGF-β and IL-10),12-14 CD4+CD25- T cells from naïve mice and mice immunized with different vaccines were isolated, purified and analyzed by flow cytometry using intracellular staining with specific fluorescently labeled antibodies. As shown in Figure 7, percentages of Foxp3+IL-10+ or Foxp3+TGF-β+ cells among CD4+CD25- cells were significantly increased in the co-immunized mice as compared with other vaccine groups, indicating suppressive iTregs were induced.

Figure 7. Increase in percentages of Foxp3+IL-10+ and Foxp3+TGF-β+ cells among CD4+CD25- cells in co-immunized mice. Seven days after the second immunization, single splenocyte suspensions were prepared and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Percentages of Foxp3+IL-10+ (upper) and Foxp3+TGF-β+ cells (lower) among CD4+CD25- cells. Percentages of double positive cells were shown. (B) Statistical analysis of percentages of Foxp3+IL-10+ cells and Foxp3+TGF-β+ cells in CD4+CD25- T cells (n = 3). Compared with other groups, percentages of double positive cells among CD4+CD25- T cells in the co-immunization group increased significantly (p < 0.05). Numbers in the outlined areas indicate percentage of cells. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments with the same number of mice per group. * p < 0.05.

Protection against allergic airway inflammation induced by nFel d 1 by adoptive transfer of CD4+CD25- T cells

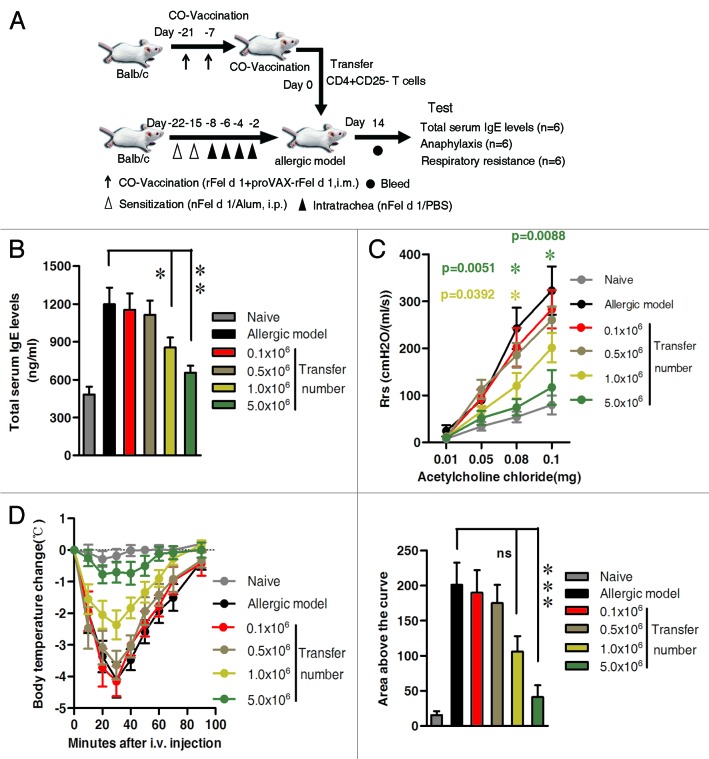

To determine whether the CD4+CD25- iTregs play a crucial role in inhibiting signs of allergic airway inflammation in the allergic model, we adoptively transferred CD4+CD25- T cells taken from the BALB/c mice previously co-immunized (Donor) to the nFel d 1-induced allergic model mice (Recipient). To optimize transfer dose, we injected intravenously 0.1 × 106, 0.5 × 106, 1.0 × 106 and 5.0 × 106 CD4+ CD25- T cells to allergic mice, respectively. Correspondingly, naïve mice and the allergic mice were respectively served as the negative control and positive control.

As shown in Figure 8, total serum IgE decreased significantly in the 1.0 × 106 recipient group (p < 0.05) and 5.0 × 106 recipient group (p < 0.005), compared with the allergic model. Likewise, AHR results also confirmed that values of Rrs were obviously lower after transferring 1.0 × 106 (at 0.08 mg dose, p = 0 0.0392) and 5.0 × 106 cells (at 0.08 mg, p = 0.0051 and at 0.1 mg doses, p = 0.0088, respectively, Fig. 8C). Moreover, body temperature drops remained relatively stable (left panel in Fig. 8D) and the area above the curves reduced significantly in 5.0 × 106 recipient group (p < 0.0001, right panel in Fig. 8D). Therefore, 5.0 × 106 dosage was selected for future experiments.

Figure 8. Descrease in total serum IgE levels, reduction of AHR and inhibition of anaphylactic reaction by adoptively transfer CD4+CD25- T cells from co-immunized mice. CD4+CD25- T cells from co-immunized mice were isolated, purified and adoptively transferred intravenously to nFel d 1-induced allergic mice as described in Materials and Methods. Four different transfer groups received the following four doses of cells: 0.1 × 106, 0.5 × 106, 1.0 × 106 and 5.0 × 106. The nFel d 1-induced allergic airway inflammation mice without adoptive transfer served as a positive control. Naïve BALB/c mice without sensitization and transfer served as a negative control. (A) Schematic outline of the experiment. (B) 14 d after CD4+CD25- T cells transfer, serum of individual asthmatic mouse was collected. Mean total serum IgE levels ± SD are shown (n = 6). For 1.0 × 106 recipient group vs. model group, p < 0.05; for 5.0 × 106 recipient group vs. model group, p < 0.005. (C) AHR was measured by the RC system in mice in response to the intra-jugular administration of acetylcholine chloride at various doses on the x-axis and expressed as Rrs on the y-axis (n = 6). (D) 15 d after adoptive transfer, 6 mice in each group were challenged i.v. with rFel d 1 and body temperature was measured at regular intervals. Changes in body temperature in degrees Celsius ± SD (n = 6) are shown on the left panel and mean area above the curves ± SD (n = 6) on the right panel. Individual areas above the curves were determined and compared by one-way ANOVA using Bonferroni’s post test. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments with six mice per group. (B and C) * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005; D: *** p < 0.0001; ns, no significant difference.

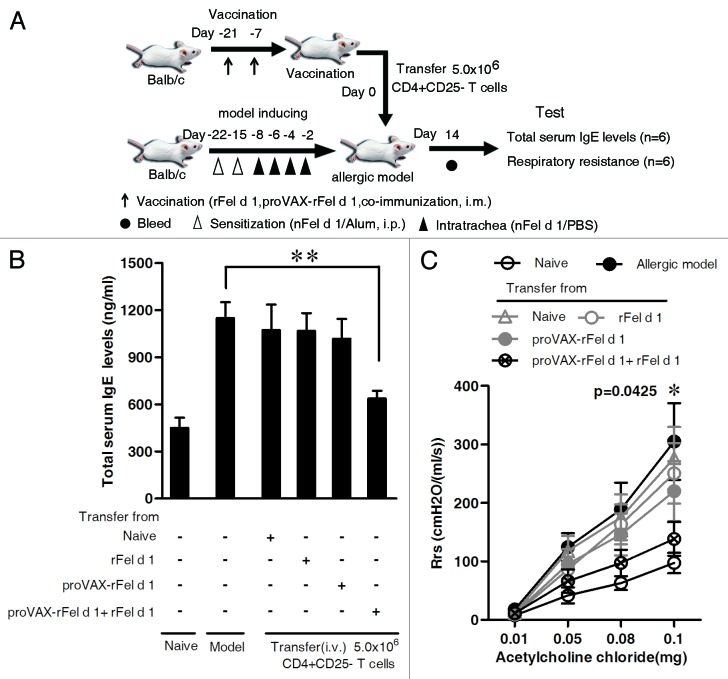

To exclude the possibility that CD4+ CD25- T cells from other vaccine groups (except for co-immunization group) could alleviate allergic symptoms in mice, we then adoptively transferred 5.0 × 106 CD4+ CD25- T cells isolated from mice either immunized with DNA vaccine, protein vaccine, or DNA/protein co-vaccine to nFel d 1-induced allergic airway inflammation mice. Allergic mice were transferred with 5.0 × 106 CD4+ CD25- T cells derived from naïve mice served as a negative control, naïve mice without any treatment served as a blank control and allergic mice as a positive control. It was found that only CD4+ CD25- T cells from the co-immunization group, compared with allergic model group, could significantly inhibit the increase in total serum IgE levels (Fig. 9B) and reduce Rrs (p = 0.0425 at 0.1 mg dose, Fig. 9C), suggesting that co-immunization initiated the suppression of already established allergic reaction via induction of CD4+ CD25- iTreg.

Figure 9. Effect of adoptive transfer of CD4+CD25- T cells from co-immunized mice on total serum IgE levels and AHR. CD4+CD25- T cells from different vaccine groups were isolated, purified and adoptively transferred intravenously to nFel d 1-induced allergic airway inflammation mice as described in Materials and Methods. Adoptively transferred CD4+CD25- T cells were 5.0 × 106 cells per mouse. Four different transfer groups were set up [i.e., CD4+CD25- T cells were derived from naïve mice, BALB/c mice vaccinated with rFel d 1 alone, proVAX-rFel d 1 alone or proVAX-rFel d 1 and rFel d 1 mixture (1:1), respectively]. The nFel d 1-induced allergic mice without adoptive transfer served as positive control and the naïve BALB/c mice without sensitization and transfer served as blank control. (A) Schematic outline of the experiment. (B) Fourteen days after CD4+CD25- T cells transfer, serum of individual mouse was collected. Mean total serum IgE levels ± SD are shown (n = 6). (C) AHR was measured by the RC system in mice in response to the intra-jugular administration of acetylcholine chloride at various doses on the x-axis and expressed as Rrs on the y-axis (n = 6). Data shown are representative of two independent experiments with six mice per group. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005.

Discussion

We previously delineated that induction of iTreg inhibits antigen specific effector T-cells in vivo by co-inoculating antigen-matched DNA and protein vaccines,10,11 which proved the suppression of autoimmune and allergic disease in mouse model.8,9,15,16 In the present study, we describe a novel therapy for cat allergy with Fel d 1 co-immunization vaccine. The co-inoculation therapy relieved the established allergic airway inflammation in mice sensitized by nFel d 1 through inducing the adaptive CD4+ CD25-Foxp3+ iTreg cells expressing IL-10 and TGF-β, which was further confirmed by the suppression test in vitro (Fig. S6).

To date, although allergen-specific immunotherapies are effective for allergy and have shown successes in some disease-modifying therapies,17,18 the procedures are time consuming and even require 1–3 y of regular treatments.6,7 Therefore, development of tolerance by SIT-treatment is a cost-efficient alternative to treat allergy.

We previously reported that co-immunization with protein antigen and sequence matched DNA could lead to antigen-specific immune suppression whereas protein or DNA vaccination alone did not result in immune suppression. Conversely, T cell reactivity was enhanced in DNA or protein alone immunized mice.8,10 Furthermore, co-immunization vaccine could induce regulatory DCs through co-uptaking of DNA and protein immunogens by the same DCs via caveolae-mediated endocytosis. This process upregulated Tollip and downregulated the phosphorylation of Cav-1, which in turn downregulates NF-κB and STAT-1α and upregulates SOCS1 in the downstream signaling pathway. The DCregs induced by co-immunization vaccine showed CD11c+CD80+CD86+CD40lowIL-10+ phenotype8,19 and could convert naive T cells into Ag-specific regulatory T cells of a CD4+CD25-Foxp3+IL-10+ phenotype in vitro and in vivo,8 which in turn mediated Ag-specific tolerance.8-11,16

Interestingly, the CD4+CD25- iTregs induced by co-immunization is different than Tr1 cells. CD25- iTregs lack IL-2Rα, and are unable to deprive IL-2 from environment as CD25+ Tregs do.20 In addition, CD25- iTreg express low levels of CTLA-4, PD-1, high level of GITR (unpublished data), which is abnormal in CD25+ Tregs. Moreover, CD25- iTreg can be induced systematically by i.m. or s.c. immunization,10 but Tr1 is mainly induced in mucosal tract. Although SIT also can induce a specific Treg response, the Treg phenotypes induced by SIT were not the same as the iTreg induced by co-immunization. Recent data indicate that allergen-specific IL-10-secreting TR1-like cells and CD4+CD25+ regulatory Treg cells21-27 and CD4+CD25-Foxp3- Treg cells28 were boosted by SIT.

Although the requirement for weak antigen stimulation is well established for the induction of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ iTreg, we have previously confirmed that highly antigenic T cell epitope is required for efficient induction of CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ iTreg in co-immunization strategy.29 Thus, it is important to identify Fel d 1 antigenic epitopes for T cells to induce the CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ iTreg cells more effectively for cat allergy therapy. Previous epitope-mapping studies identified the immunodominant epitopes of Fel d 1 in chain 1, but not chain 2, of the molecule.30,31 In contrast, Reefer and coworkers proposed that the major T cell epitopes is localized in chain 2.32 In the context, DNA vaccine and protein vaccine contain both chain 1 and chain 2 in order to include all possible epitopes of Fel d 1. Moreover, it has been recently demonstrated that the recombinant Fel d 1 protein with a direct linkage of chain 1 to chain 2 expressed both in prokaryotic and eukaryotic displays similar tertial structure and immunoreactivity to the native tetramer allergen (e.g., nFel d 1),4,33-35 implying the probable reason why the co-immunization strategy can suppress already established allergic mice induced by nFel d 1.

Fel d 1, a major cat allergen inducing allergic rhinitis and asthma in sensitized individuals, is currently used for diagnosis of cat allergy. Allergic symptoms induced by Fel d 1 include rhinitis, conjunctivitis, allergic inflammation and even life-threatening asthmatic responses. However, it is not easy to avoid exposure to Fel d 1, because it is often associated with small particles that easily become airborne and remain airborne for long periods,36,37 which would allow the allergens to circulate and settle throughout a house. Previously, Fel d 1 therapies have been reported, including hypoallergens immunotherapy,38 T-cell epitope therapy39-42 and Fel d 1-coupled immunomodulatory carrier therapy.43-47 Here, we designed a co-immunization strategy with rFel d 1 protein plus its cognate DNA vaccine for cat allergy through inducing the adaptive CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ T regulatory cells, suggesting a new potential application for cat allergy and an alternative cat allergy treatment. With further study, the co-immunization vaccine, which is very easy to implement in a very short period of time, can be used for treating cat-allergic patients in the future.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Adult female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks) were purchased from The Animal Institute of Chinese Medical Academy (Beijing, China) and maintained in pathogen-free environment. All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by Experimental Animal Committee of China Agricultural University.

Cloning, expression and purification of rFel d 1

A covalent fusion of rFel d 1 was generated as previously described35 with modifications. Sequences of chain 1 and chain 2 encoding cat allergen Fel d 1 were optimized and synthesized. The Fel d 1(1+2) construct was created by directly linking the C-terminal residue of chain 1 (Cys70) to the N-terminal residue of chain 2 (Val70) using overlapping oligonucleotides in PCR. This cDNA was cloned in frame into a modified version of pET-28a(+) (Novagen), leading to the addition of the sequence of the ubiquitin-like protein SMT3 at the N terminus of the covalent dimer in order to enhance the solubility of the fusion protein. An ubiquitin-like specific protease Ulp1 recognition site was also added at 3′ end of SMT3 so that rFel d 1 protein can be cleaved from the fusion protein molecule after expression in Escherichia coli (Fig. S1). The resultant expression vector was named as pET28a-SMT3-rFel d 1. Then pET28a-SMT3-rFel d 1 was transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3) pLysS. Expression of pET28a-SMT3-rFel d 1 was induced at 37°C with 1 mM IPTG. After 5 h, cells were harvested, resuspended in native lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazol, pH 8.0) and disrupted by sonication. The fusion protein His tag-SMT3-rFel d 1 was Ni2+ affinity purified using Ni-NTA agarose (Cat. No. 30210, Qiagen). rFel d 1 protein was then cleaved from the fusion protein by adding protease His tag-Ulp1 to the elution fractions at 4°C. After 3 h, the imidazole concentration in the elution fraction was reduced to 10 mM using Ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra-15ml, 3KD, Millipore). The protein solution was passed over a chromatography column containing nickel (Ni-NTA agarose, Cat. No. 30210, Qiagen). As a result, His tag-SMT3 and His tag-Ulp1 ligated the nickel and attached to the column while rFel d 1 protein was passed through the column. Imidazole in purified rFel d 1 was then removed by Ultrafiltration and protein was concentrated to 10 mg/ml in PBS.

For eukaryotic expression vector proVAX-rFel d 1, sequences of chain 1 and chain 2 encoding cat allergen Fel d 1 were cloned from cat skin cDNA and directly linked the C-terminal residue of chain 1 (Cys70) to the N-terminal residue of chain 2 (Val70) using overlapping PCR. Then the chain 1-chain 2 was cloned in frame into the modified vector proVAX. The constructed vector proVAX-rFel d 1 could successfully express Fel d 1 antigen in HEK293 cells, which had been proved by western blot (Fig. S1D).

Sensitization and vaccination

Sensitization

For nFel d 1 protein sensitization, naïve BALB/c mice (6–8wk) were injected i.p. with 1.5 μg of nFel d 1 (Indoors Biotechnologies, Product Code: NA-FD1–2) mixed in 100 μl of Alum (50 mg/ml Al(OH)3; Sigma-Aldrich) on day 0 and day 7. Subsequently, intra-tracheal challenges were performed. In brief, mice were anesthetized by inhalation of ether, followed by delivery of 1 μg of nFel d 1 to the back of the tongue of each animal on days 14, 16, 18 and 20.

Vaccination

Adult female BALB/c mice (6–8 wk) were vaccinated with rFel d 1 protein (100 μg/mouse), plasmid proVAX-rFel d 1 (100 μg/mouse) or their mixture (100 μg protein and 100 μg plasmid/mouse) into tibialis anterior muscle. Plasmid proVAX-rFel d 1 and rFel d 1 protein were dissolved in PBS and then used for vaccine. All mice were immunized on day 0 and boosted on day 14. All experiments were repeated three times.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)

Immediately after i.p. injection with an overdose of pentobarbital, 0.8mL of saline was instilled twice via the tracheal cannula and recovered by gentle manual aspiration. BAL collected from one mouse was pooled, centrifuged and cells were resuspended in 1 mL of saline containing 0.1% BSA. Total BAL cells were counted by cell counting chamber and the differential cell counts on at least 200 cells were performed on May–Grunwald-Giemsa stain using standard morphological criteria. Three mice in each group were measured by BAL method.

Respiratory resistance

Dynamic respiratory resistance (Rrs) was measured in mice in response to 50μL of acetylcholine chloride intra-jugular administrated at various doses in the Resistance and Compliance (RC) system (model AniRes2005; Beijing Bestlab Technology Co. Beijing, China). Briefly, 72 h after final challenge, mice were anaesthetized, tracheotomized and connected to the ventilator. Mechanical ventilation was performed, dynamic airway pressure (ΔP) and volume of chamber (ΔV) were recorded and peak resistance and compliance were automatically measured as Rrs = ΔP/(ΔV/ΔT) after each 50 μL of intra-jugular administration of various doses of acetylcholine chloride (mg).48 Six mice of each treatment group were used for analysis of the Rrs.

Histology and inflammation score

Lung samples from mice were collected from each group, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin blocks. Sections were then cut and fixed. Antigen retrieval was accomplished by boiling the slides in 0.01M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) followed by staining with H&E for evaluation of cell invasion and analyzed under a light microscope for determining histology changes.

Lung inflammation was blindly scored. A value from 0 to 3 per criterion was adjudged to evaluate the degree of peribronchial inflammation, as described elsewhere.49,50 A value of 0 was for no inflammation, a value of 1 was for occasional cuffing with inflammatory cells, a value of 2 for most bronchi surrounded by thin layer (one to five cells) of inflammatory cells and a value of 3 was for most bronchi surrounded by a thick layer (more than five cells thick) of inflammatory cells. Each group used 5 mice for HE staining and scoring analysis.

Isolation of CD4+CD25- T cells and adoptive transfer

Single splenocyte suspensions were prepared from mouse spleen and T cell subtypes of CD4+CD25− were isolated and purified by using the MagCellect Mouse CD4+CD25+ T Cell Isolation Kit according to manufacturer’s protocol (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). The purity of the selected cell populations was 94–96%. A certain number of CD4+CD25− T cells were adoptively transferred intravenously to BALB/c allergic mice pre-induced by nFel d 1 protein.

Acute systemic anaphylaxis

For the induction of anaphylaxis, mice were challenged i.v. with 50 μg of rFel d 1 / 100 μl PBS. Temperature was measured with an Infrared Thermometer immediately after i.v. antigen challenge and monitored for a maximum of 100 min after challenge. For statistical analysis, the area above the curve was determined using Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Six mice of each treatment group were used for the induction of acute systemic anaphylaxis.

Measurement of total serum IgE levels

Total serum IgE levels were measured using double-antibody sandwich ELISA technique (Mouse Immunoglobulin E (IgE) ELISA Kit, DongGe Biotechnology, Beijing). Measurements were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry

CD4+CD25-Foxp3+ iTreg were detected by immunostaining with anti-CD4-FITC, anti-CD25-APC and anti-Foxp3-PE mAbs. For analysis of cytokine profile of CD4+CD25- Treg cells, CD4+CD25- T cells were isolated and purified after the second immunization. Co-expression of Foxp3 and IL-10 were detected by intracellular staining with anti-Foxp3-APC mAb and anti-IL-10-PE mAb. Similarly, Co-expression of Foxp3 and TGF-β were detected by intracellular staining with anti-Foxp3-APC mAb and anti-TGF-β-PE mAb. Data were collected with a BD FACSCalibur and analyzed with Flowjo (Tree Star).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis comparing two different groups were performed with two tailed Student’s t tests. The resulting p-values are either indicated in figure legends or with asterisks in figures (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.005; *** p < 0.001). For statistical analysis of anaphylaxis experiments, individual areas above the curves were determined and compared by one-way ANOVA using Bonferroni’s multiple comparison posttests (* p < 0.01; ** p < 0.001; *** p < 0.0001).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by National High-tech R&D Program of China (2006AA02Z148) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (30871783) and the Earmarked Fund for Modern Agro-industry Technology Research System (CARS-40–08). We thank Zhonghuai He, Yiwei Zhong, Xiaoping Xie and Huiyuan Zhang for their excellent technical assistance in this work. We also thank Jin-an Jiao Ph.D. for correcting the English language in revised manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- nFel d 1

Natural Fel d 1

- rFel d 1

Recombinant Fel d 1

- iTreg

Inducible T regulatory cell

- AHR

Airway hyperreactivity

- Rrs

Respiratory resistance

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/vaccines/article/23518

References

- 1.Georas SN, Guo J, De Fanis U, Casolaro V. T-helper cell type-2 regulation in allergic disease. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:1119–37. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00006005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgenstern JP, Griffith IJ, Brauer AW, Rogers BL, Bond JF, Chapman MD, et al. Amino acid sequence of Fel dI, the major allergen of the domestic cat: protein sequence analysis and cDNA cloning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:9690–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mata P, Charpin D, Charpin C, Lucciani P, Vervloet D. Fel d I allergen: skin and or saliva? Ann Allergy. 1992;69:321–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Ree R, van Leeuwen WA, Bulder I, Bond J, Aalberse RC. Purified natural and recombinant Fel d 1 and cat albumin in in vitro diagnostics for cat allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:1223–30. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohman JL, Jr., Lowell FC, Bloch KJ. Allergens of mammalian origin. III. Properties of a major feline allergen. J Immunol. 1974;113:1668–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedlin G, Graff-Lonnevig V, Heilborn H, Lilja G, Norrlind K, Pegelow KO, et al. Immunotherapy with cat- and dog-dander extracts. II. In vivo and in vitro immunologic effects observed in a 1-year double-blind placebo study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;77:488–96. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(86)90184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedlin G, Graff-Lonnevig V, Heilborn H, Lilja G, Norrlind K, Pegelow K, et al. Immunotherapy with cat- and dog-dander extracts. V. Effects of 3 years of treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87:955–64. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90417-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin H, Kang Y, Zhao L, Xiao C, Hu Y, She R, et al. Induction of adaptive T regulatory cells that suppress the allergic response by coimmunization of DNA and protein vaccines. J Immunol. 2008;180:5360–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin H, Xiao C, Geng S, Hu Y, She R, Yu Y, et al. Protein/DNA vaccine-induced antigen-specific Treg confer protection against asthma. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2451–63. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang Y, Jin H, Zheng G, Du X, Xiao C, Zhang X, et al. Co-inoculation of DNA and protein vaccines induces antigen-specific T cell suppression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:1034–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin H, Kang Y, Zheng G, Xie Q, Xiao C, Zhang X, et al. Induction of active immune suppression by co-immunization with DNA- and protein-based vaccines. Virology. 2005;337:183–91. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–6. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roncarolo MG, Bacchetta R, Bordignon C, Narula S, Levings MK. Type 1 T regulatory cells. Immunol Rev. 2001;182:68–79. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2001.1820105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stock P, Akbari O, Berry G, Freeman GJ, Dekruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Induction of T helper type 1-like regulatory cells that express Foxp3 and protect against airway hyper-reactivity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1149–56. doi: 10.1038/ni1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Jin H, Hu Y, Yu Y, Li X, Ding Z, et al. Protective response against type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice after coimmunization with insulin and DNA encoding proinsulin. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:171–8. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Jin H, Zhang F, Du X, Zhao G, Yu Y, et al. Treatment of autoimmune ovarian disease by co-administration with mouse zona pellucida protein 3 and DNA vaccine through induction of adaptive regulatory T cells. J Gene Med. 2008;10:810–20. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durham SR, Till SJ. Immunologic changes associated with allergen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:157–64. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70079-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Till SJ, Francis JN, Nouri-Aria K, Durham SR. Mechanisms of immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1025–34, quiz 1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Geng S, Xie X, Liu H, Zheng G, Sun X, et al. Caveolin-1-mediated negative signaling plays a critical role in the induction of regulatory dendritic cells by DNA and protein coimmunization. J Immunol. 2012;189:2852–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:523–32. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akdis CA, Blesken T, Akdis M, Wüthrich B, Blaser K. Role of interleukin 10 in specific immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:98–106. doi: 10.1172/JCI2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akdis M, Verhagen J, Taylor A, Karamloo F, Karagiannidis C, Crameri R, et al. Immune responses in healthy and allergic individuals are characterized by a fine balance between allergen-specific T regulatory 1 and T helper 2 cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1567–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ling EM, Smith T, Nguyen XD, Pridgeon C, Dallman M, Arbery J, et al. Relation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell suppression of allergen-driven T-cell activation to atopic status and expression of allergic disease. Lancet. 2004;363:608–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15592-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jutel M, Akdis M, Budak F, Aebischer-Casaulta C, Wrzyszcz M, Blaser K, et al. IL-10 and TGF-beta cooperate in the regulatory T cell response to mucosal allergens in normal immunity and specific immunotherapy. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1205–14. doi: 10.1002/eji.200322919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verhoef A, Alexander C, Kay AB, Larché M. T cell epitope immunotherapy induces a CD4+ T cell population with regulatory activity. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei W, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhao Y, He J, Li X, et al. Induction of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+IL-10+ T cells in HDM-allergic asthmatic children with or without SIT. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;153:19–26. doi: 10.1159/000301575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su W, Zhong W, Zhang Y, Xia Z. Synthesized OVA323-339MAP octamers mitigate OVA-induced airway inflammation by regulating Foxp3 T regulatory cells. BMC Immunol. 2012;13:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-13-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Xiang L, Liu YG, Wang YH, Shen KL. Effect of house dust mite immunotherapy on interleukin-10-secreting regulatory T cells in asthmatic children. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:2099–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geng S, Yu Y, Kang Y, Pavlakis G, Jin H, Li J, et al. Efficient induction of CD25- iTreg by co-immunization requires strongly antigenic epitopes for T cells. BMC Immunol. 2011;12:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-12-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Counsell CM, Bond JF, Ohman JL, Jr., Greenstein JL, Garman RD. Definition of the human T-cell epitopes of Fel d 1, the major allergen of the domestic cat. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:884–94. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(96)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mark PG, Segal DB, Dallaire ML, Garman RD. Human T and B cell immune responses to Fel d 1 in cat-allergic and non-cat-allergic subjects. Clin Exp Allergy. 1996;26:1316–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1996.tb00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reefer AJ, Carneiro RM, Custis NJ, Platts-Mills TAE, Sung S-SJ, Hammer J, et al. A role for IL-10-mediated HLA-DR7-restricted T cell-dependent events in development of the modified Th2 response to cat allergen. J Immunol. 2004;172:2763–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaiser L, Grönlund H, Sandalova T, Ljunggren H-G, van Hage-Hamsten M, Achour A, et al. The crystal structure of the major cat allergen Fel d 1, a member of the secretoglobin family. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37730–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grönlund H, Bergman T, Sandström K, Alvelius G, Reininger R, Verdino P, et al. Formation of disulfide bonds and homodimers of the major cat allergen Fel d 1 equivalent to the natural allergen by expression in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40144–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaiser L, Velickovic TC, Badia-Martinez D, Adedoyin J, Thunberg S, Hallén D, et al. Structural characterization of the tetrameric form of the major cat allergen Fel d 1. J Mol Biol. 2007;370:714–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luczynska CM, Li Y, Chapman MD, Platts-Mills TA. Airborne concentrations and particle size distribution of allergen derived from domestic cats (Felis domesticus). Measurements using cascade impactor, liquid impinger, and a two-site monoclonal antibody assay for Fel d I. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:361–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Custovic A, Green R, Fletcher A, Smith A, Pickering CA, Chapman MD, et al. Aerodynamic properties of the major dog allergen Can f 1: distribution in homes, concentration, and particle size of allergen in the air. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:94–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saarne T, Kaiser L, Grönlund H, Rasool O, Gafvelin G, van Hage-Hamsten M. Rational design of hypoallergens applied to the major cat allergen Fel d 1. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:657–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keating KM, Segal DB, Craig SJ, Nault AK, Semensi V, Wasserman AS, et al. Enhanced immunoreactivity and preferential heterodimer formation of reassociated Fel d I recombinant chains. Mol Immunol. 1995;32:287–93. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(94)00140-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Metre TE, Jr., Marsh DG, Adkinson NF, Jr., Fish JE, Kagey-Sobotka A, Norman PS, et al. Dose of cat (Felis domesticus) allergen 1 (Fel d 1) that induces asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;78:62–75. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(86)90116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcotte GV, Braun CM, Norman PS, Nicodemus CF, Kagey-Sobotka A, Lichtenstein LM, et al. Effects of peptide therapy on ex vivo T-cell responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:506–13. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pène J, Desroches A, Paradis L, Lebel B, Farce M, Nicodemus CF, et al. Immunotherapy with Fel d 1 peptides decreases IL-4 release by peripheral blood T cells of patients allergic to cats. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:571–8. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu D, Kepley CL, Zhang K, Terada T, Yamada T, Saxon A. A chimeric human-cat fusion protein blocks cat-induced allergy. Nat Med. 2005;11:446–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terada T, Zhang K, Belperio J, Londhe V, Saxon A. A chimeric human-cat Fcgamma-Fel d1 fusion protein inhibits systemic, pulmonary, and cutaneous allergic reactivity to intratracheal challenge in mice sensitized to Fel d1, the major cat allergen. Clin Immunol. 2006;120:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hulse KE, Reefer AJ, Engelhard VH, Satinover SM, Patrie JT, Chapman MD, et al. Targeting Fel d 1 to FcgammaRI induces a novel variation of the T(H)2 response in subjects with cat allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:756–62, e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersson TN, Ekman GJ, Grönlund H, Buentke E, Eriksson TL, Scheynius A, et al. A novel adjuvant-allergen complex, CBP-rFel d 1, induces up-regulation of CD86 expression and enhances cytokine release by human dendritic cells in vitro. Immunology. 2004;113:253–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmitz N, Dietmeier K, Bauer M, Maudrich M, Utzinger S, Muntwiler S, et al. Displaying Fel d1 on virus-like particles prevents reactogenicity despite greatly enhanced immunogenicity: a novel therapy for cat allergy. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1941–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moisan J, Camateros P, Thuraisingam T, Marion D, Koohsari H, Martin P, et al. TLR7 ligand prevents allergen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilia in allergic asthma by a MYD88-dependent and MK2-independent pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L987–95. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00440.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tournoy KG, Kips JC, Schou C, Pauwels RA. Airway eosinophilia is not a requirement for allergen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:79–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwak YG, Song CH, Yi HK, Hwang PH, Kim JS, Lee KS, et al. Involvement of PTEN in airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in bronchial asthma. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1083–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI16440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.