The repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) is highly complex. To maintain genome integrity and avoid tumorigenesis, cells choreograph the 2 major DSB repair pathways, nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR), both spatially and temporally through post-translational modifications.1 DSBs activate ATM kinase, which triggers a signaling cascade, leading to activation of cell cycle checkpoints and DNA repair. There is also growing evidence implicating cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) in the regulation of DSB repair.2 CDKs, first discovered for their role in cell cycle regulation, belong to a large superfamily of proline-directed kinases that exclusively phosphorylate serine or threonine residues preceding a proline (S/T-P motifs). The unique stereochemistry of proline allows prolyl-peptide bonds to adopt cis and trans conformations. The intrinsically slow interconversion between these isomers can be greatly accelerated by peptidyl-prolyl isomerases (PPIases). PPIases include 3 major subfamilies (cyclophilins, FKBPs, and parvulins) that act in general protein folding, but only one enzyme, Pin1, can isomerize phosphorylated S/T-P motifs.3 By inducing conformational changes in a subset of phosphorylated proteins, Pin1 was shown to act as a molecular switch in multiple cellular processes.4 Most recently, we showed that Pin1 also has a profound impact on the regulation of DSB repair.5

In order to identify novel Pin1-interacting proteins, we performed GST pull-down assays using Pin1 as bait and analyzed the recovered proteins by mass spectrometry. Interestingly, the list of >600 specific interactors included the key DSB response factors MDC1, 53BP1, BRCA1, BARD1, PTIP, and CtIP. This prompted us to test the involvement of Pin1 in GFP-based HR and NHEJ reporter assays. We found that depletion of Pin1 caused a significant decrease in NHEJ frequency, while Pin1 overexpression led to a strong reduction in HR. Since DNA-end resection constitutes a critical point in DSB repair pathway choice, we reasoned that Pin1 may restrict HR and promote NHEJ by actively suppressing the formation of single-stranded DNA. This hypothesis was substantiated by increased hyperphosphorylation of RPA2 and a concomitant defect in NHEJ upon DSB induction in Pin1−/− MEFs. Moreover, the observed hyper-resection phenotype of Pin1-depleted cells was strictly dependent on CtIP, which plays a key role in the initiation of DNA-end resection.

Confirming our proteomics screen data, we could show that Pin1 binds to CtIP in a phosphorylation-dependent manner and identified 2 conserved S/T-P motifs in CtIP (S276 and T315) to be required for Pin1 interaction. We could show that CtIP-pT315 serves as the major Pin1 binding site, but that CtIP isomerization takes place exclusively at the pS276-P277 site. In order to identify the kinase(s) responsible for phosphorylating CtIP at S276 and T315, we raised individual phospho-specific antibodies and used them in combination with various kinase inhibitors. Treatment of cells with roscovitine, a pan-CDK inhibitor, strongly reduced both Pin1-CtIP interaction and T315 (but not S276) phosphorylation. Consistently, overexpression of dominant-negative (dn) forms of CDKs resulted in a strong (CDK2-dn) or moderate (CDK1-dn) reduction of Pin1-CtIP interaction. We also monitored CtIP phosphorylation levels during the cell cycle, and found that pT315 was upregulated during S phase and peaked in late S/G2, whereas pS276 was largely undetectable. In fact, we noticed that the region encompassing S276 is highly conserved in mammals and rather matches the consensus sequence for mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), with some family members known to be activated in response to DNA damaging agents.6 Interestingly, we observed a slight increase in Pin1-CtIP complex formation in presence of DSBs. These observations are consistent with a fascinating kinase convergence mechanism, in which CDK1/2-mediated T315 phosphorylation is a prerequisite for Pin1 recognition, while S276 phosphorylation by another DNA damage-inducible proline-directed kinase is crucial for CtIP isomerization.

To investigate the role of CtIP isomerization at the molecular and cellular level, we generated cell lines stably expressing siRNA-resistant GFP-tagged wild type or mutant CtIP, in which both S276 and T315 were changed to non-phosphorylatable residues (CtIP-2A). Importantly, we observed increased resection of DSBs and reduced NHEJ capacity in the mutant cells, reminiscent of Pin1-depleted cells. Hyper-resection of DNA ends was particularly evident when CtIP-2A mutant cells were irradiated in late S/G2, supporting the notion that Pin1-mediated CtIP isomerization limits resection in a cell cycle-dependent manner. Our results may help explain why DSBs in G2 are preferentially repaired by NHEJ, although both repair pathways are available.7

We detected increased CtIP protein levels after Pin1 depletion, or reduced amounts of CtIP upon Pin1 overexpression. Since prolyl isomerization by Pin1 was shown to regulate the stability of many of its target proteins, we speculated that Pin1 may accelerate CtIP turnover by promoting its proteasomal degradation. Indeed, CtIP polyubiquitination was severely compromised in both Pin1-depleted cells and in cells expressing the CtIP-2A mutant. This implies that CtIP is selectively polyubiquitinated upon isomerization by an as-yet-unidentified ubiquitin ligase.

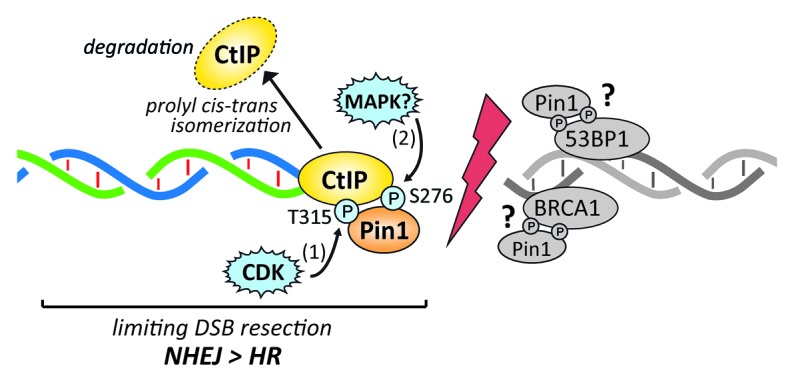

Our data strongly link Pin1 to the DNA damage response, particularly in the regulation of DSB repair (Fig. 1). It remains to be seen whether other factors identified in our screen, such as BRCA1-BARD1 or 53BP1, key players in the regulation of DSB repair pathway choice8 that contain multiple phosphorylated S/T-P motifs, are also Pin1 targets.

Figure 1.

Model of Pin1-mediated restriction of DNA-end resection. During S/G2 phase of the cell cycle, CtIP is phosphorylated at residue T315 by CDK2 and/or CDK1. This priming phosphorylation event is necessary for Pin1 binding to CtIP. Upon DSB formation, CtIP is further phosphorylated at residue S276 by an as-yet-unknown proline-directed kinase (e.g., MAPKs) and subsequently isomerized by Pin1. This conformational change promotes CtIP polyubiquitination, leading to its proteasomal degradation. In this way, Pin1 counteracts DNA-end resection and hence HR, thereby facilitating NHEJ. Our proteomics screen revealed that 53BP1 and BRCA1 could be additional Pin1 substrates. Due to their opposite roles in the regulation of DSB repair pathway choice, it will be interesting to determine whether Pin1-mediated isomerization may positively (53BP1) or negatively (BRCA1) modulate their functions in NHEJ and HR, respectively.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/26077

References

- 1.Chapman JR, et al. Mol Cell. 2012;47:497–510. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferretti LP, et al. Front Genet. 2013;4:99. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaffe MB, et al. Science. 1997;278:1957–60. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5345.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liou Y-C, et al. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:501–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steger M, et al. Mol Cell. 2013;50:333–43. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinhardt HC, et al. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:175–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karanam K, et al. Mol Cell. 2012;47:320–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunting SF, et al. Cell. 2010;141:243–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]