Abstract

The current study examined how parental ethnic socialization informed adolescents’ ethnic identity development and, in turn, youths’ psychosocial functioning (i.e., mental health, social competence, academic efficacy, externalizing behaviors) among 749 Mexican-origin families. In addition, school ethnic composition was examined as a moderator of these associations. Findings indicated that mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization were significant longitudinal predictors of adolescents’ ethnic identity, although fathers’ ethnic socialization interacted significantly with youths’ school ethnic composition in 5th grade to influence ethnic identity in 7th grade. Furthermore, adolescents’ ethnic identity was significantly associated with increased academic self-efficacy and social competence, and decreased depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors. Findings support theoretical predictions regarding the central role parents play in Mexican-origin adolescents’ normative developmental processes and adjustment and, importantly, underscore the need to consider variability that is introduced into these processes by features of the social context such as school ethnic composition.

Keywords: Ethnic identity, Mexican-origin, early adolescents, social context, ethnic socialization, psychosocial adjustment

Ecological theory posits that proximal and distal contextual factors interact with one another and with individual characteristics to inform developmental processes and outcomes (Bronfenbrenner, 1989). An important normative developmental process for ethnic minority youth in the U.S. is their ethnic identity formation (Umaña-Taylor, 2011). Ethnic identity is one component of adolescents’ broader identity, and those who have explored and resolved the meaning of ethnic identity are theorized to be better prepared to navigate their social worlds and make sense of experiences they may encounter, such as discrimination (Neblett, Rivas-Drake, & Umaña-Taylor, 2012; Umaña-Taylor, Vargas-Chanes, Garcia, & Gonzales-Backen, 2008). Indeed, there is some support for this notion in work that has identified positive associations between adolescents’ ethnic identity and indicators of positive adjustment (Ojeda, Pina-Watson, Castillo, Castillo, Khan, & Leigh, 2011; Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2007).

Consistent with an ecological framework, a significant body of work has identified the family as a critical context that informs youths’ ethnic identity development (Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993; Supple, Ghazarian, Frabutt, Plunkett, & Sands, 2006; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, Bámaca, & Guimond, 2009). An important limitation inherent in existing work, however, is the lack of simultaneous examination of these associations. For example, some studies have examined familial ethnic socialization as a predictor of ethnic identity (e.g., Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004), while others have examined how ethnic identity is associated with youth outcomes (e.g., Romero & Roberts, 2003); but few have simultaneously tested ethnic identity as a mediator of the associations between family ethnic socialization experiences and adolescents’ adjustment. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no studies have examined how additional characteristics of youths’ proximal ecologies (e.g., ethnic composition of school setting) may further modify the associations between ethnic socialization and ethnic identity, and between ethnic identity and adolescents’ adjustment. Such an examination is consistent with scholars’ recommendations to use an ecological approach to understand developmental processes and outcomes among ethnic minority youth (García Coll et al., 1996). The current study attempts to fill this gap by simultaneously examining complex associations among multiple variables.

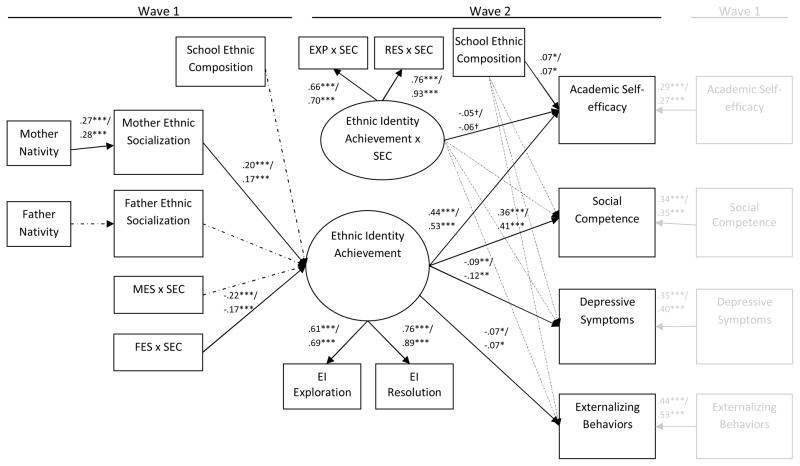

Guided by notions from ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1989), the current study examined the interaction between a proximal microsystem (i.e., parent-child ethnic socialization experiences) and a more distal exosystem (i.e., ethnic composition of school) during the 5th grade to inform adolescents’ ethnic identity in 7th grade; in addition, we examined the concurrent associations among adolescents’ ethnic identity (i.e., an individual characteristic), school ethnic composition (i.e., a feature of the exosystem), and psychosocial functioning in various domains (i.e., depressive symptoms, social competence, externalizing behaviors, and academic efficacy) during the 7th grade (see Figure 1 for conceptual model) while controlling for the 5th grade reports on the outcomes. This study provides an opportunity to empirically examine key tenets of ecological theory, which suggest that features of environmental settings (e.g., family and school context) interact with one another to inform development (e.g., ethnic identity) and, further, that individual characteristics (e.g., ethnic identity) interact with features of the environment (e.g., school context) to inform human development and adjustment. We focus on Mexican-origin youth in the U.S. for three important reasons: (a) individuals of Mexican-origin represent a large and rapidly growing population, comprising 66% of the U.S. Latino population and 10% of the U.S. general population (U.S. Census, 2011); (b) Mexican-origin youth account for almost 15% of all youth in the U.S. (Hernandez, Macartney, Blanchard, & Denton, 2010); and (c) Mexican-origin adolescents are at significant risk for psychological maladjustment (Roberts, Roberts, & Chen, 1997) and engagement in risk behaviors (Flores, Tschann, Dimas, Pasch, & de Groat, 2010). Thus, understanding normative developmental processes and links to positive adjustment among Mexican-origin youth carries significant practical implications. Specifically, addressing the gaps in the extant literature will not only significantly advance ethnic identity theory but will also provide counselors, clinicians, and intervention specialists with tangible information regarding how these contexts interact and inform youth development and adjustment.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

Family as an Important Predictor of Ethnic Identity

We conceptualize ethnic identity as a developmental process (i.e., exploration of one’s ethnicity, and resolution regarding the meaning ethnicity has for oneself) that also carries an affective component (i.e., content; the degree to which individuals feel positively about their ethnic group membership; Phinney, 1993; Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009). The focus of the current study, on understanding how development unfolds within Mexican-origin youth’s ecological contexts, directs our attention to the developmental components of ethnic identity (i.e., exploration and resolution; see Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gomez, 2004). Guided by ecological models that emphasize the central influence of the family context on youths’ identity development (e.g., Knight, Bernal et al., 1993; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004), and work that underscores the significance of the family for Mexican-origin individuals (Ojeda, Navarro, & Morales, 2011), we focus specifically on how mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization practices inform adolescents’ ethnic identity exploration and resolution.

Existing work with Latino (Supple et al., 2006) and Mexican-origin (Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004) adolescents has provided support for the positive associations between familial ethnic socialization practices and adolescents’ ethnic identity exploration and ethnic identity resolution during middle adolescence. Moreover, with a predominantly Mexican-origin Latino sample, Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, and colleagues (2009) found that family ethnic socialization during mid-adolescence was associated with increased exploration and resolution two years later, documenting the potential long-term impact of family ethnic socialization on youth’s exploration and resolution. Limitations of this existing work, however, include (a) relying exclusively on youth perceptions of familial ethnic socialization and, thus, increasing the potential that shared method variance may partly explain the significant associations that have emerged; and (b) not differentiating between fathers’ and mothers’ ethnic socialization efforts. A few studies have noted the important role that Mexican-origin fathers play in their children’s lives (e.g., Parke, Coltrane, Duffy, Buriel, Dennis, Powers, French, & Widaman, 2004; White & Roosa, 2012), but for the most part, Latino fathers have received little attention in empirical work (Cabrera & García Coll, 2004); thus, an examination of fathers’ unique contributions to youths’ identity formation and adjustment is sorely needed. Finally, the existing work has been based largely on the developmental periods of middle and late adolescence, and it is unclear whether familial ethnic socialization efforts in early adolescence have a long-term impact on ethnic identity.

Our own work, using the same sample described in the current study, has addressed these limitations by examining whether mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of ethnic socialization during adolescents’ 5th grade year significantly predicted youths’ ethnic identity exploration and resolution two years later (Knight et al., 2011). In the current study, we extend this previous work by examining the potential mediating role of ethnic identity in the associations between mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization and adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment.

Furthermore, as introduced below, we examine how school context may modify the associations between parents’ ethnic socialization and adolescents’ adjustment.

Ethnic Identity as an Important Predictor of Youth Adjustment

Turning to psychosocial adjustment, developmental theory suggests that achieving a stable identity is a key developmental task that has a considerable impact on individuals’ psychosocial adjustment (Erikson, 1968). Based on Erikson’s work, scholars studying ethnic identity suggest that adolescents who have explored their ethnic group membership and feel a sense of resolution regarding the meaning that their ethnicity has in their lives may demonstrate better psychosocial adjustment (Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen et al., 2009). Indeed, numerous studies have found a significant and positive association between Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity and their self-esteem (Roberts, Phinney, Masse, Chen, Roberts, & Romero, 1999; Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2007; Umaña-Taylor, 2004). In addition, among Mexican-origin adolescents, Ojeda and colleagues (2012) found ethnic identity to be positively associated with career decision self-efficacy, and Roberts et al. (1999) found ethnic identity to be positively associated with coping, mastery, and optimism. Researchers also have found ethnic identity resolution, specifically, to be positively linked to Latino adolescents’ use of proactive strategies for coping with discrimination (Umaña-Taylor, Vargas-Chanes, Garcia, & Gonzales-Backen, 2008).

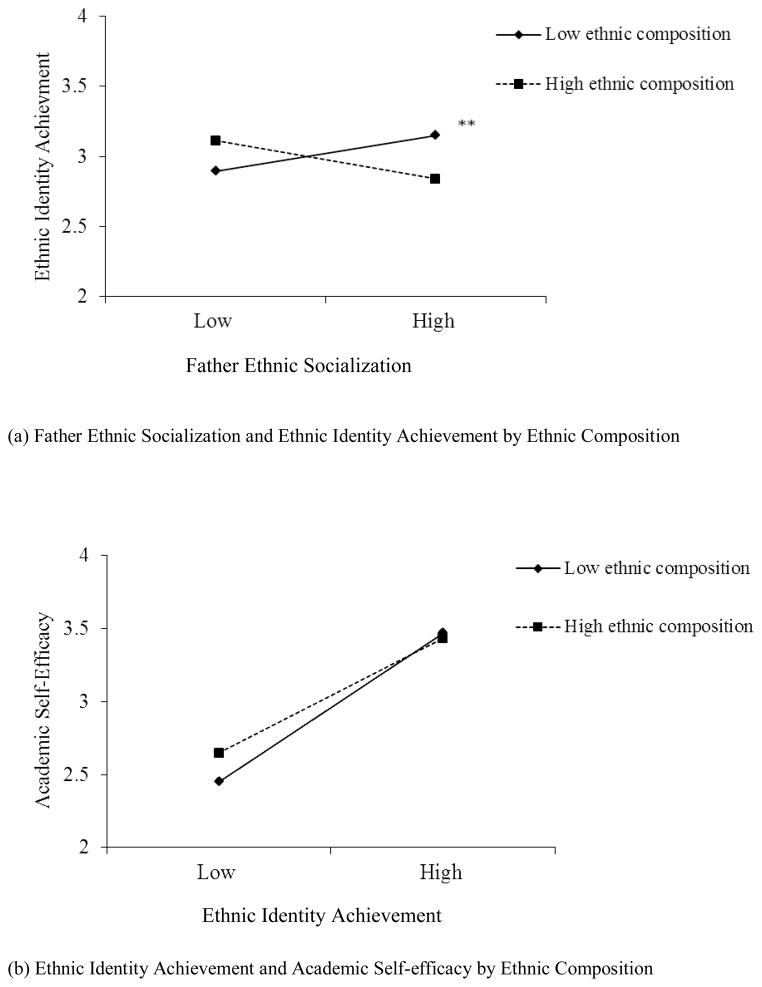

Several studies also have found a positive association between familial ethnic socialization and youth adjustment (for a review, see Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson, & Spicer, 2006). Because existing theory and longitudinal evidence suggest that familial ethnic socialization plays a critical role in shaping youths’ ethnic identity (Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro et al., 2009), and youths’ ethnic identity is expected to be linked to their adjustment (Schwartz et al., 2007), it is a strong possibility that the positive association that has emerged between familial ethnic socialization and youths’ adjustment is mediated by youths’ ethnic identity. In fact, scholars suggest that ethnic socialization may foster the development of an achieved ethnic identity that, in turn, may foster a variety of positive psychological outcomes (Knight et al., 2011). The current study tests this possibility with a mediational model in which mothers’ and fathers’ reports of ethnic socialization are examined as predictors of adolescents’ ethnic identity exploration and resolution (i.e., ethnic identity achievement) two years later and, in turn, as predictors of change in adolescents’ adjustment during this same time (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Final structural model of ethnic socialization, adolescent ethnic identity, and adolescent adjustment. Standardized coefficients are presented for girls/boys; all paths were constrained to be equal across gender. Dashed lines are not significant. 0 = U.S. born, 1 = Mexico born. χ2 (284) = 455.10, p ≤ .001; RMSEA = .04 (.03 – .05); CFI = .91; SRMR = .07. MES = Mother Ethnic Socialization, FES = Father Ethnic Socialization; EXP = Exploration; RES = Resolution; SEC = School Ethnic Composition; EI = Ethnic Identity. One-tailed significance tests presented at *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; † p < .10.

School Ethnic Composition as a Proximal Ecological Factor Informing These Associations

As noted by Bronfenbrenner’s (1989) ecological framework, human development is informed by characteristics of the immediate settings in which individuals’ lives are embedded as well as by the larger contexts in which these more immediate settings are entrenched. Applying this to ethnic identity, two settings in which youths’ lives are firmly embedded during adolescence are the family and school contexts. As noted above, a key goal of the current study was to examine how familial ethnic socialization informed youths’ ethnic identity development. In an effort to provide a more nuanced test of ecological theory, we take this analysis one step further by examining how a second contextual factor may inform the associations among familial ethnic socialization, ethnic identity, and youth adjustment. Specifically, we examined the extent to which these processes varied as a function of adolescents’ school setting.

Family ethnic socialization and ethnic identity: Variability by school context

Family is an important context for youth identity formation and, as noted previously, a significant body of work has supported the notion that family ethnic socialization efforts are important for adolescents’ ethnic identity formation (e.g., Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro et al., 2009). However, the degree to which youth internalize ethnic socialization messages from their parents may vary based on other features of their social ecologies. Scholars suggest that the school context plays a critical role in youth development by interacting with individuals’ characteristics to inform adolescent development and outcomes (Eccles & Roeser, 2003). Thus, the school context may shape how adolescents interpret and internalize messages from parents regarding their ethnicity.

For instance, self-categorization theory suggests that being in a numerical minority is likely to make one’s social group membership salient (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). Thus, school contexts in which an adolescent’s ethnic group is a numerical minority may increase the salience of ethnicity. Accordingly, Umaña-Taylor (2004) found that Mexican-origin adolescents attending a school with a student body of over 96% Latino students reported significantly lower ethnic identity than their counterparts attending a school with a 15% Latino student body. Umaña-Taylor suggested that ethnicity is increasingly salient in contexts where one’s ethnic group is a numerical minority, and that this increased salience may come from youth having to answer questions about their ethnicity or simply being faced with the realization of being an out-group member of the dominant ethnic group in their schools.

Given the potential for increased salience of ethnicity in a minority context, parents’ ethnic socialization could lead to greater ethnic identity exploration and resolution among Mexican-origin youth in such a context because youth are already facing questions about their ethnicity in the school setting (i.e., having to answer the “What are you?” question), which may be prompting the process of exploration and resolution. In a school context that has a large population of same-ethnic group peers, parents’ socialization messages may have a more limited impact on the process of ethnic identity formation because youth may take parents’ efforts and messages for granted. When the school context is more consonant, parents’ socialization efforts may be useful and may initiate a process of exploration and resolution, but because ethnicity is less salient and youth may see less of a need for such exploration, the association may be weaker. As such, we hypothesized that the positive association between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity would be significantly stronger among youth attending schools in which they were a greater numerical minority (i.e., lower Latino student representation).

Ethnic identity and adolescent adjustment: Variability by school context

In a similar vein, the impact that ethnic identity may have on youths’ adjustment may vary considerably based on characteristics of the school context. For youth who are numerical ethnic minorities in their schools, ethnic identity may be especially important for youth adjustment because youth may be relying on this aspect of their identity to inform their general sense of self, given its salience (Umaña-Taylor & Shin, 2007). Indeed, research with African Americans has noted that perceptions of discrimination are greater in school contexts that have fewer same-ethnic peers (Seaton & Yip, 2009), and that individuals feel more accepted in contexts with more same-ethnic peers (Postmes & Branscombe, 2002). Given the established link between perceived discrimination and Mexican-origin youths’ adjustment (Berkel et al., 2010; Delgado, Updegraff, Roosa, & Umaña-Taylor, 2011; Romero & Roberts, 2003), it is possible that school contexts with fewer same-ethnic peers are more threatening to youths’ psychosocial adjustment, making the potential positive effects of ethnic identity on psychosocial adjustment particularly consequential. Furthermore, in an ethnically dissonant context, having an informed understanding of one’s ethnicity may be necessary for positive adjustment because it is in such contexts that youth may be ‘called out’ on their ethnicity and will need to have the knowledge, confidence, and skills to process such exchanges. Thus, in settings where ethnicity is less salient, the link between ethnic identity and adjustment may be weaker.

The Current Study

The current study provides an empirical examination of theoretical notions from ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1989). Specifically, we hypothesized that the positive associations between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity, and between ethnic identity and adolescent adjustment, would be significantly stronger among youth attending schools with relatively fewer same-ethnic peers. Our hypotheses were tested in a structural equation model that enabled us to test whether adolescents’ ethnic identity mediated the association between mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization and adolescents’ adjustment (see Figure 2).

Parents’ nativity status was included as a predictor of their ethnic socialization efforts, given previous work establishing this association (e.g., Knight et al., 2011; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004). Furthermore, we explored gender as a moderator of the associations of interest given that gender differences have emerged in the links between culturally informed processes and youth adjustment among Latino adolescents (e.g., Alfaro, Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, Bamaca, & Zeiders, 2009; Delgado et al., 2011).

Importantly, we tested our hypotheses using multiple reporters’ accounts and tested multiple indices of youth adjustment that captured the domains of education, externalizing behaviors, peer relationships, and mental health. An examination of education-related outcomes is important because Mexican-origin youth in the U.S. are at high risk for poor academic outcomes (Pew Hispanic Center, 2004). Furthermore, academic failure and externalizing behaviors have been identified as key indicators of a broader construct of adolescent problem behavior (Dishion & Patterson, 2006). A focus on youths’ social competence with peers also is important during adolescence given that peer relations become increasingly salient during adolescence and are an important predictor of later adjustment (Brown & Larson, 2009; Wentzel, Baker, & Russell, 2009). Finally, given Mexican-origin youths’ increased risk for psychological maladjustment (Roberts et al., 1997), examining mental health as an indicator of adjustment is particularly important. Specifically, we examined depressive symptoms because Latino youth demonstrate an elevated risk for depressive symptomatology (Anderson & Mayes, 2010).

Method

Data came from the first two waves of a longitudinal study investigating the role of culture and context in the lives of Mexican American families (N = 749; Roosa et al., 2008). Families with a 5th grade student were recruited from elementary schools in a large southwestern metropolitan area. Recruitment materials were sent home with students and over 86% were returned. To be eligible to participate: (a) families had to have a fifth grader attending a sampled school; (b) both mother and child had to agree to participate (all fathers were encouraged, but not required, to participate; over 80% of fathers from two-parent families (n = 466) participated); (c) the mother had to be the child’s biological mother, live with the child, and self identify as Mexican or Mexican American; (d) the child’s biological father had to be of Mexican origin; (e) the child could not be severely learning disabled; and (f) no step-father or mother’s boyfriend could be living with the child (to minimize in-home exposure to other cultures).

At Wave 1 (W1), 77.2% of families were two-parent families; this number decreased slightly to 74.6% at W2. In contrast to the majority of previous studies of Mexican American families, this sample was diverse on SES indicators, generational status, and language preference. Family income ranged from less than $5,000 to more than $95,000, with the average family reporting an income of $30,001 – $35,000 at W1 and W2. About 30% of mothers, 14% of fathers, and over 80% of adolescents (48.9% female) were interviewed in English. The mean age of mothers, fathers, and adolescents at W1 was 35.9, 38.1, and 10.4 years, respectively. At W1, mothers and fathers reported an average of 10.3 and 10.1 years of education, respectively. A majority of mothers (74%) and fathers (80%) were born in Mexico, and a majority of adolescents were born in the U.S. (70%). Of the families in the study in which both mothers and fathers participated (n = 466), 74% were dyads in which both partners were born in Mexico, 15% were dyads in which both were U.S. born, and 10% were dyads in which one parent was born in Mexico and one was U.S. born.

Procedure

The complete procedures are described elsewhere (Roosa et al., 2008). Here we summarize key features of the study. Using a combination of random and purposive sampling, the research team identified communities served by 47 public, religious, and charter schools from throughout a southwestern U.S. metropolitan area that represented the economic, cultural, and social diversity of the community. Recruitment materials were sent home with all children in the 5th grade in these schools, and over 86% returned materials. Participants completed computer-assisted personal interviews that lasted about 2.5 hours. Interviewers read questions and response options aloud in the participants’ preferred language, and participants were paid $45 and $50 each at W1 and W2, respectively. Comparisons with the U.S. Census data for the metropolitan area from which families were recruited indicated that the current sample was similar to the local Mexican American population in terms of parental education, father’s employment status, income, and children’s language (Roosa et al., 2008).

Measures

Nativity

Mothers and fathers were asked to report the country in which they were born at W1 (1 = U.S.; 2 = Mexico).

Ethnic composition

Ethnic composition was computed using school data retrieved from the Arizona Department of Education (2005). The variable used in the current study represented the percentage of Latino students in adolescents’ grade within each school during the spring of their fifth and seventh grade year in school. Higher values indicated a greater percentage of Latino students in adolescents’ grade level at their school.

Ethnic socialization

Ethnic socialization was assessed with an adaptation of the 10-item Ethnic Socialization Scale from the Ethnic Identity Questionnaire (e.g., Knight, Bernal et al., 1993). This study used 15 items that represented the extent to which mothers and fathers socialized children into Mexican culture (e.g., “How often do you encourage [target child] to speak Spanish”). Responses ranged from Almost never or never (1) to A lot of the time/frequently (4). Cronbach’s alphas were .73 for mothers and .75 for fathers. Support for validity of the measure emerged in early work conducted by Knight et al. (1993), in which the measure was associated in a theoretically expected manner with mothers’ cultural orientation and with children’s ethnic behaviors, self-identification, and knowledge. For the current measure and all measures described below, participants were asked to think about the timeframe of the past three months.

Ethnic identity

Adolescent ethnic identity was assessed using the exploration (7 items; e.g., “I have attended events that have helped me learn more about my ethnicity”) and resolution (4 items, e.g., “You are clear about what your background means to you”) subscales of the Ethnic Identity Scale (EIS; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). Participants responded using options ranging from Not at all true (1) to Very true (5). In prior work with Latino adolescents, the exploration and resolution subscales of the EIS demonstrated internal consistency (e.g., alphas above .83; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010). Support for construct validity has been demonstrated by positive associations between each subscale and measures of family ethnic socialization (e.g., Supple et al., 2006) and self-esteem (e.g., Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007) with Latino samples. Alphas in the current study were .73 (exploration) and .86 (resolution).

Academic self-efficacy

Adolescents’ reports on academic self-efficacy were assessed using the mastery subscale of the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Survey (Midgley, Maehr, & Urdan, 1996). Items are not specific to subject matter or tasks, and instead specific to students’ classroom experiences (e.g., “I am certain I can master the skills taught in school this year”). Students responded to the six items with options ranging from Not at all true (1) to Very true (5). Alpha coefficients were .75 and .79 at W1 and W2, respectively. In a prior study that included Latinos students (Conley, 2012), subscales demonstrated adequate reliability (α = .86) and, providing support for validity of the measure, students characterized by high levels of mastery beliefs scored higher on achievement and affect (Conley, 2012).

Social competence

Adolescents’ reports on social competence were assessed using the peer competence subscale of the Coatsworth Competence Scale (Coatsworth & Sandler, 1993). Each item was an indicator of adolescents’ manifest behaviors, rather than his/her capacity for effective behavior or perceived competence (e.g., “You get along well with others your age). Adolescents responded to eight items with options ranging from Not at all true (1) to Very true (5). Alpha coefficients were .64 and .70 at W1 and W2, respectively. In a study with Mexican Americans in California (Taylor, et al., 2012), support for the validity of the subscale emerged when it was positively associated with nurturant parenting, which was consistent with theory.

Depressive symptoms

Both mothers and children reported children’s depressive symptomatology using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). The current study utilized the major depressive disorder (MDD) symptom count within the past year to assess youths’ depressive symptoms. Mother and child reports were combined such that a given symptom was considered present if reported by either; this approach is consistent with common clinical and research practice (e.g., Shaffer et al., 2000). The reliability and validity of the DISC is well established (Shaffer et al., 2000). With a sample largely comprised of Latino students (i.e., 46% of the sample), Jones et al. (2010) found that a school-based program targeting socio-emotional development effectively reduced depressive symptoms in this sample, as measured via the DISC. Comparing our sample to that of Jones et al., MDD symptom count was similar (i.e., Mcount = 3.0 vs Mcount = 2.94).

Externalizing behaviors

Both mothers and children reported children’s externalizing behaviors using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (Shaffer et al., 2000). The indicators of externalizing behaviors used were adolescent conduct disorder (CD) and opposition defiant disorder (ODD) symptoms. Given that CD and ODD often co-occur in this age group and that CD is thought of as a precursor to ODD (Hinshaw & Zupan, 1997), these symptom counts were summed into a combined CD/ODD score. Similar to depressive symptoms, mother and adolescent reports were combined. In a study with Mexican American adolescents (Lau, et al., 2005), findings supporting the hypothesized positive relation between family conflict and conduct problems provide support for the validity of the measure.

Analytic Approach

Prior to examining our hypothesized model, we tested a measurement model using confirmatory factor analysis to determine whether the observed variables in our model reliably assessed their respective latent constructs (Hatcher, 1994). After establishing adequate model fit for our measurement model, we proceeded to test our hypothesized model using multiple group analyses within a structural equation modeling framework, with gender as the grouping variable. This allowed us to examine whether there were gender differences in the paths estimated in our hypothesized model. Using the χ2 difference test (Kline, 1998), we compared a model in which all estimates were free to vary across groups to a model in which all of the paths were constrained to be equal across groups. A significant change in chi square coupled with a significantly poorer fit for the fully constrained model would indicate that all paths in the model could not be constrained to be equal (Kline, 1998). Subsequent models would then be tested to identify which specific paths must be free to vary across group. After arriving at a final model for both boys and girls, mediation analyses were conducted using the bias-corrected empirical bootstrap method (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004) to construct confidence intervals that estimate indirect effects. Analyses were conducted with Mplus 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2009), and multiple fit indices were used to conclude acceptable model fit: CFI above .90, and SRMR and RMSEA below .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 1998; 2005).

Missing data were handled using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (Arbuckle, 1996; Schafer & Graham, 2002). At W2, two years after W1, 95% of families were retained. Families who were not retained were compared to those retained on key W1 demographic variables and no differences emerged on child characteristics (i.e., gender, age, generational status, language of interview), mother characteristics (i.e., marital status, age, generational status), or father characteristics (i.e., age, generational status). Given that fathers’ participation was optional, we were missing data on father variables in 38% of cases; however, as noted by Enders (2010), FIML is robust to parameter bias caused by missing cases in excess of this.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables are presented in Table 1. Descriptives are presented separately for boys and girls.

Table 1.

Zero-order correlations among study variables for females (above diagonal; n = 366) and males (below diagonal; n = 383)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mother Nativity | -- | .34** | .74** | .08 | .24** | .28** | −.04 | −.08 | −.07 | −.20** | .10 | .09 | −.05 | −.08 | −.02 | −.15** |

| 2. Mother Eth Soc W1 | .25** | -- | .34** | .18** | .11 | .09 | .03 | −.06 | −.02 | −.12** | .21** | .13* | .04 | .08 | .01 | −.09 |

| 3. Father Nativity | .62** | .22** | -- | .02 | .21** | .15* | .09 | −.06 | .05 | −.11 | .20* | .17* | .12 | −.01 | −.02 | −.14** |

| 4. Father Eth Soc W1 | .15** | .30** | .10 | -- | .13 | .16* | −.06 | −.05 | −.01 | .01 | .06 | .06 | −.08 | −.12 | −.01 | .03 |

| 5. Ethnic composition W1 | .11** | .10 | .21** | .05 | -- | .64** | .04 | .04 | −.02 | −.03 | .04 | .06 | .12* | .08 | −.04 | −.06 |

| 6. Ethnic composition W2 | .07 | .06 | .17* | .03 | .71** | -- | −.01 | .02 | .00 | −.06 | .02 | −.02 | .08 | .04 | −.01 | −.09 |

| 7. Academic self-efficacy W1 | −.02 | .08 | −.06 | .07 | .05 | −.01 | -- | .43** | −.10 | −.16** | .15** | .18** | .42** | .30** | −.09 | −.07 |

| 8. Social Competence W1 | .03 | .10* | −.07 | .06 | −.07 | −.06 | .43** | -- | −.12* | −.09 | .08 | .13* | .19** | .34** | −.16** | −.10 |

| 9. Depressive Symptoms W1 | −.12* | −.05 | −.02 | −.06 | −.05 | −.02 | −.04 | −.08 | -- | .41** | −.04 | −.02 | −.02 | −.05 | .46** | .31** |

| 10. Externalizing W1 | −.21** | −.09 | −.13** | −.14* | .05 | .04 | −.12* | −.14** | .41** | -- | −.00 | −.01 | −.10 | −.03 | .25** | .46** |

| 11. EI Exploration W2 | .02 | .14** | −.01 | .07 | .00 | .03 | .21** | .30** | .04 | −.07 | -- | .46** | .30** | .27** | −.03 | −.03 |

| 12. EI Resolution W2 | .02 | .14** | .05 | .01 | −.08 | −.08 | .20** | .19** | −.01 | −.01* | .62** | -- | .38** | .31** | −.09 | −.09 |

| 13. Academic self-efficacy W2 | −.04 | .05 | −.06 | .03 | .01 | .01 | .38** | .25** | −.07 | −.21** | .37** | .49** | -- | .51** | −.16** | −.14** |

| 14. Social Competence W2 | −.01 | .08 | −.09 | −.01 | −.03 | −.02 | .29** | .48** | −.05 | −.23** | .40** | .38** | .49** | -- | −.12** | −.10** |

| 15. Depressive Symptoms W2 | −.01 | −.08 | .06 | −.06 | .02 | −.01 | −.08 | −.13* | .36** | .35** | −.09 | −.09 | −.15** | −.17** | -- | .51** |

| 16. Externalizing W2 | −.15** | −.08 | −.07 | .00 | .04 | .01 | −.07 | −.11* | .23** | .62** | −.07 | −.09 | −.21** | −.24** | .49** | -- |

| M Boys | 1.73 | 3.07 | 1.78 | 3.03 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 4.38 | 4.00 | 3.29 | 1.03 | 3.71 | 4.28 | 4.22 | 3.72 | 3.00 | 1.30 |

| SD | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 2.74 | 1.10 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 2.43 | 1.29 |

| M Girls | 1.76 | 3.13 | 1.82 | 3.00 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 4.37 | 4.03 | 3.04 | 0.76 | 3.76 | 4.35 | 4.21 | 3.89 | 3.07 | 1.14 |

| SD | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 2.59 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 2.71 | 2.00 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01.

W1 = Wave 1, W2 = Wave 2, Eth Soc = Ethnic Socialization, EI = Ethnic Identity.

Measurement Model

As described above, we first tested a measurement model to confirm the methodological appropriateness of estimating the two latent constructs in our hypothesized model (i.e., ethnic identity [EI] achievement; the interaction term for EI achievement x school ethnic composition). EI achievement was defined by two observed variables, which were drawn from two subscales of the EIS: EI exploration and EI resolution (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). The latent interaction construct was defined by 2 observed interaction terms (i.e., EI exploration x school ethnic composition; EI resolution x school ethnic composition). All variables were standardized at the individual level to get accurate interaction terms for the interactions being tested. Examination of the measurement model indicated an acceptable fit to the data [χ2 (12) = 19.19, p = .08; CFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.02].

Hypothesized Model

The initial estimated model (i.e., the unconstrained model) allowed all paths and covariances to freely estimate across gender. This model fit the data adequately [χ2 (261) = 432.56, p < .001; CFI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.06]. To initiate the process of examining moderation by gender, a second model was tested in which all of the paths were constrained to be equal across gender. Findings indicated the constrained model also fit the data adequately [χ2 (284) = 455.10, p < .001; CFI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.07] and did not significantly differ from the model in which all paths were freely estimated [χ2(23) = 23.54, ns]. Therefore, the fully constrained model was chosen as the final model because it was the more parsimonious of the two models (Figure 2).

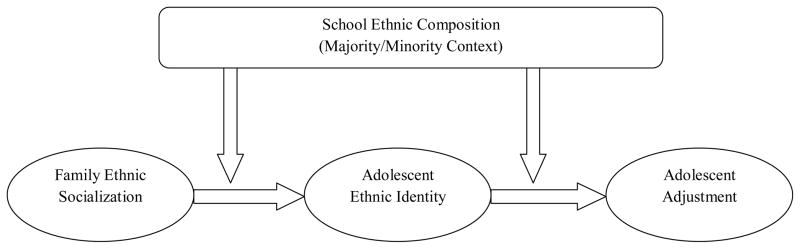

Positive associations emerged between mother nativity and mother ethnic socialization as well between mother ethnic socialization and EI achievement. Furthermore, EI achievement positively predicted adolescent academic self-efficacy and social competence, whereas it negatively predicted depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors. Finally, school ethnic composition was a significant moderator of the relation between father ethnic socialization and EI achievement, and a trend emerged suggesting school ethnic composition may also moderate the relation between EI achievement and academic self-efficacy. All path coefficients are standardized, which is one approach to demonstrate effect size in more complex, multivariate regression models (Peterson & Brown, 2005; Trusty, Thompson, & Petrocelli, 2004).

To probe the interaction involving father ethnic socialization and EI achievement we followed guidelines by Aiken and West (1991) in which we examined simple regression slopes. We graphed the relation between father ethnic socialization and EI achievement at varying levels of school ethnic composition (i.e., the moderator). The moderator was graphed at one standard deviation above the mean (i.e. high, greater than 92%) and one standard deviation below the mean (i.e., low, less than 46%). As shown in Figure 3a, we found a positive relation between father ethnic socialization and EI achievement at lower levels of school ethnic composition (β = .23, p < .01) and no significant relation at higher levels of ethnic composition (β = −.11, p = .19).

Figure 3.

Moderation effects of school ethnic composition on the association between (a) father ethnic socialization and ethnic identity achievement, and (b) ethnic identity achievement and academic self-efficacy. ** Denotes significant slope at p < .01.

We were unable to statistically probe the marginal interaction effect involving EI achievement and self-efficacy, as there are not yet statistical procedures available to test significant interactions in which the independent variable is a latent construct (Tein, February 7, 2011, personal communication). Nevertheless, we were able to graph the interaction, which allowed us to interpret the direction of effects at varying levels of the moderator. Findings indicated that the relation between EI achievement and academic self-efficacy was positive at both lower and higher levels of school ethnic composition; however, this relation appeared to be stronger when school ethnic composition was lower (see Figure 3b).

Mediation Analyses

Results from the final model showed that four of the mediation paths were significant. Specifically, (a) mother nativity was related to EI achievement through its positive association with mother ethnic socialization (Indirect effect = .07, CI = .04, .12), (b) mothers’ ethnic socialization related to academic self-efficacy through its positive association with EI achievement (Indirect effect = .05, CI = .03, .08), (c) mothers’ ethnic socialization related to social competence through its positive association with EI achievement (Indirect effect = .04, CI = .02, .05), and (d) mothers’ ethnic socialization related to depressive symptoms via its positive association with EI achievement (Indirect effect = −.05, CI = −.01, −.02). Because there were no direct effects from the independent variable to each of the dependent variables, our findings suggest full mediation for each of the effects described above.

Discussion

Ethnic identity has been identified as a normative developmental process among Latino youth (Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen et al., 2009). Using a multi-informant, longitudinal design, findings from the current study extend previous theoretical and empirical work in a number of ways. First, findings linking ethnic identity exploration and resolution to four indices of adolescent adjustment support the notion that ethnic identity may serve an important promotive function for Mexican-origin adolescents. Second, our findings indicating that familial ethnic socialization interacted with youths’ school context to influence youths’ ethnic identity provide support for the notion that contexts interact with one another to inform development (Bronfenbrenner, 1989). Finally, the current study provides strong longitudinal support for the notion that mothers’ and fathers’ reports of ethnic socialization efforts during early adolescence predict adolescents’ ethnic identity development two years later.

Familial Ethnic Socialization among Mexican-origin Families

A number of studies have noted a positive association between familial ethnic socialization and Latino and Mexican-origin adolescents’ ethnic identity with cross-sectional data (e.g., Supple et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004). The current findings extended previous work by examining this association longitudinally, examining the unique influence of mothers’ and fathers’ ethnic socialization efforts, and utilizing parents’ reports rather than relying on adolescents’ self-reports. Importantly, we extended our own prior work (Knight et al., 2011) by examining whether mothers’ and fathers’ unique influence on adolescents’ ethnic identity varied as a function of social context and, indeed, the findings of the current study suggest that fathers’ influence appears to be relatively more contextually informed. Specifically, our findings indicated that fathers’ ethnic socialization efforts were associated with increased exploration and resolution, but only when youth were in a school context that had fewer Latino students (i.e., fewer than 46% Latinos). This distinction is critical given that in our previous study (Knight et al., 2011) we only examined the direct association between fathers’ ethnic socialization and adolescent ethnic identity and, in fact, concluded that fathers’ ethnic socialization was not significantly associated with youth ethnic identity. The current findings, however, suggest that fathers’ influence is evident only under certain conditions.

It is possible that fathers are keenly aware of the ethnic characteristics of the schools that their children attend and perhaps modify the manner in which they convey ethnic socialization messages to their children based on their perceptions of what their adolescents need when they are in a school context with few ethnic group members, which then has a stronger impact on adolescents’ ethnic identity. This idea is supported by a small body of literature that has investigated the effects of neighborhood on racial/ethnic socialization and found that African American parents’ racial socialization efforts (preparation for bias, specifically) were greater when they resided in neighborhoods where they were not the majority (i.e. operationalized as more cultures represented in the neighborhood) as compared to when they resided in predominately Black neighborhoods (Stevenson, Herrero-Taylor, et. al, 2002, Stevenson, McNeil, Herrero-Taylor, & Davis, 2005). It is important to note that school ethnic composition is often a proxy indicator of other processes such as intergroup conflict and support. Thus, these variables may also inform parents’ socialization efforts and should be examined.

Another possibility is that adolescents who attend schools in which they are significant minority may rely more heavily on messages from all socialization agents to make meaning of their experiences relating to ethnicity. Likely, it is a combination of both factors at work, given that parents and adolescents both play an active role in the process of socialization and development. Because of the lack of prior work from which to draw conclusions, our ideas are speculative and underscore the need for further research.

Turning to mothers, it is possible that we see no moderation by social context in this association for mothers because of the critical role that mothers play in the process of cultural transmission; indeed, previous work has demonstrated that youths’ self-identifications are more influenced by maternal than paternal ethnic identifications (Rumbaut, 1994). Thus, regardless of whether ethnicity is salient, youth benefit from mothers’ socialization attempts. However, it also is important to consider that fathers’ socialization efforts may be particularly consequential for youth who are attending schools in which their ethnic group is a significant minority. For youth in such contexts, it seems that an additional effort should be made to encourage mothers and fathers to expose youth to their ethnicity and partake in other socialization activities that may help to increase youths’ exploration and resolution of their ethnic identity. This recommendation stems from existing literature that has documented (a) increased risks among youth in contexts with fewer same-ethnic group members (e.g., Seaton & Yip, 2009) and (b) a positive association between ethnic identity and youth adjustment (e.g., Ojeda et al., 2012).

Our findings also support prior theory and research suggesting that familial ethnic socialization is positively associated with youth adjustment (Hughes et al., 2006). Furthermore, our findings identify ethnic identity as a significant mediator of the links between ethnic socialization and youth adjustment. Parents’ socialization efforts may encourage youth to engage in ethnic identity exploration and resolution (Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004), which may lead to better psychosocial functioning (Neblett et al., 2012).

Finally, it is important to note that our findings suggest that the processes examined in the current study were consistent for boys and girls. Although this may seem inconsistent with prior work that has identified significant gender differences among Latino adolescents (e.g., Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010), the focus on early adolescence in the current study may help explain why the processes were similar for boys and girls. The gender intensification hypothesis suggests that boys and girls experience increased socialization pressures to conform to traditional gender roles during adolescence (Hill & Lynch, 1983). For Latino adolescents this can involve expectations for girls to follow cultural norms regarding appropriate behavior and to experience more restrictions on autonomy, which can initiate ethnic identity processes earlier for girls (Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen et al., 2009). Because the current study focused on early adolescence (and prior work has focused largely on middle to late adolescence), it is possible that the gender intensification process was only beginning and, thus, different expectations for girls and boys regarding gender roles were less pronounced given the developmental period studied.

Ethnic Identity and Mexican-origin Youth Adjustment

Another important contribution of the current study was the examination of the multiple indicators of adjustment. Conceptually, adolescents’ ethnic identity is expected to lead to better psychosocial functioning because it provides youth with a sense of purpose, an understanding of their ethnicity, and a sense of confidence regarding their ethnic group membership, which may sometimes be threatened given their ethnic minority status in the U.S. (Neblett et al., 2012; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). In the current study, adolescents’ ethnic identity had notably strong positive associations with academic self-efficacy and social competence with peers in addition to less strong (but significant) negative relations with depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors. The associations of ethnic identity with academic outcomes and social competence with peers may be particularly important given existing work noting threats ethnic minority youth face to their academic self-concept as a result of preconceived stereotypes others have of their group. Concerns about being judged based on group membership could be particularly salient in school and work environments, where these judgments could have strong consequences in one’s ability to succeed (Steele, Spencer, & Aronson, 2002). Our findings may be an indication of group identification acting as a source of confidence that may offset the negative implications of stereotyping (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999) by promoting academic self-efficacy and peer competence.

It is important to note, however, that the associations examined were concurrent and, thus, we cannot draw conclusions regarding the direction of effects. Nevertheless, based on existing theoretical work, it is expected that youth who have explored their ethnicity and have a sense of resolution regarding the meaning they attach to their ethnic group membership are better adjusted and likely have better skills to cope with potential threats to their self-concept that result from cultural stressors such as discrimination.

School Ethnic Composition as a Significant Contextual Influence on Mexican-origin Youths’ Development and Adjustment

Self-categorization theory suggests that being in a situation in which one is a numerical minority may make one’s social group membership more salient (Turner et al., 1987), and we expected that this increased salience would intensify the association between ethnic identity and adjustment. We found a trend consistent with this idea, but only for the indicator of youth adjustment capturing the educational domain. Specifically, being in a school with fewer same-ethnic peers appeared to strengthen the positive association between ethnic identity and youths’ academic self-efficacy. Because we did not find school ethnic composition to moderate the associations between ethnic identity and the other indicators of adjustment, it is possible that the manner in which context interacts with ethnic identity to inform psychosocial functioning may be largely domain specific. Put differently, the social context we chose to examine was the ethnic composition of youths’ schools, if we had examined another aspect of youths’ social context such as the ethnic composition of their peer group, perhaps this would have moderated the association between ethnic identity and adolescents’ social competence with peers. However, because this interaction was only marginally significant, it should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, we present it given the increased interest in understanding how features of the school context inform ethnic minority adolescents’ development and adjustment (e.g., García Coll et al., 1996; Umaña-Taylor, 2004) coupled with the statistical difficulty inherent in detecting significant moderation in social science research (McClelland & Judd, 1993). Future research should examine this association in a sample that captures greater variability in school ethnic composition, which would facilitate the detection of this effect if it is non-trivial. Furthermore, it will be important for future research to look beyond the ethnic composition of a school to define the school context and examine how other features of the school context (e.g., teachers’ ethnic biases, administration support for diversity) support or inhibit the process of ethnic identity development and its links to adolescents’ adjustment.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Although the current study makes several unique contributions to the literature, there are a number of limitations to consider. First, we did not examine the longitudinal associations between ethnic identity and youth adjustment. Although we controlled for prior levels of adjustment, predicting future levels of adjustment would provide a more rigorous test of this association and provide more flexibility in concluding a directional link between ethnic identity and youth adjustment. In addition, father participation was optional; thus, although over 80% of fathers participated, there is a possible selection bias skewed toward participation by more involved fathers. These limitations of our design will be important to address in future work.

Second, we focused on one aspect of youths’ school social context and only had information about the Latino (not other ethnic groups) composition of the schools. Scholars have suggested the need to look at more comprehensive measures of school ethnic composition, such as proportions of different ethnic groups or school diversity (e.g. Jackson et. al, 2006, Quintana et. al, 2006). Relatedly, future studies must capture greater variability in school contexts. In the current study only 9% of schools were considered to have high (greater that 92%) Latino composition and only 25% of schools had low (less than 42%) Latino composition. The limited variability impeded our ability to test for quadratic or curvilinear effects of ethnic composition.

Finally, future research will benefit from an examination of other influential contexts such as youths’ peer networks, after school settings, and neighborhood characteristics. An additional context to consider will be the potential dyadic effect of mothers’ and fathers’ nativity.

In our study, a majority of the sample in which both parents participated reflected parents who were both born in Mexico. It will be informative to determine whether there could be a cumulative or interactive effect of parents’ nativity on youths’ experiences with ethnic socialization. Examining the potential interaction among contexts will be an important factor to consider because, for example, the conflicting messages youth receive about their ethnicity in different contexts may prompt more exploration of ethnicity.

Conclusion

In closing, the family context is an important predictor of Mexican-origin adolescents’ ethnic identity formation and the current findings have important implications for theory building and assessment of ethnic identity, given that they suggest that drawing any conclusions regarding the antecedents and outcomes associated with ethnic identity must be considered with attention to context. In addition, consistent with a growing body of research, our findings suggest that ethnic identity is an important correlate of youth adjustment. An important next step will be to consider ethnic identity as a target for intervention, which will first involve examining its potential meditational effect on youth outcomes in a more-controlled intervention setting. Given the theoretical and empirical work linking familial ethnic socialization efforts and ethnic identity, it may be useful to examine these possibilities in a family-based intervention approach. Because several studies (some longitudinal) have supported the positive associations between ethnic identity and youth adjustment (e.g., Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen et al., 2009), and scholars encourage intervention scientists to consider culturally based strengths as targets for intervention (Case & Robinson, 2003), ethnic identity seems an ideal variable to consider.

Finally, findings from the current study identify important recommendations for practice. First, counselors and specialists who work in school settings should be aware that the ethnic composition of a school may inform the manner in which youth interpret messages about their ethnicity. Furthermore, our findings underscored the promotive nature of ethnic identity, given that higher ethnic identity was associated with better academic self-efficacy, better social competence with peers, lower depressive symptomatology, and fewer externalizing problems. Parents sometimes question whether talking to youth about ethnicity is a good option, or whether it has the potential to single them out and make them feel different from their peers; our findings indicated that, regardless of the type of school in which adolescents were enrolled, maternal ethnic socialization was associated with better psychosocial adjustment via adolescents’ ethnic identity. Thus, an important message for mothers of Mexican-origin adolescents is to encourage them to teach their children about their ethnic background and help their children develop an understanding of their Mexican heritage and the role that it may play in their overall identity.

Acknowledgments

Work on this paper was supported, in part, by grant RO1 MH 068920 (Culture, context, and Mexican American mental health), grant T-32-MH18387 to support training in prevention research at Arizona State University. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. The authors are thankful for the support of Marisela Torres, Jaimee Virgo, the La Familia Community Advisory Board, consultants, and interviewers, and the families who generously participated in the study.

References

- Alfaro EA, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales-Backen M, Bámaca MY, Zeiders K. Discrimination, Academic Motivation, and Academic Success among Latino Adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:941–962. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ER, Mayes LC. Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(3):338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Arizona Department of Education. Accountability and Performance Measures for Schools. 2005 Retrieved from Arizona Department of Education main page via School Reports/School Results link http://www.ade.azgov/srcs/statereportcards/

- Berkel C, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Tein JY, Roosa MW, Gonzales NA, Saenz D. Discrimination and adjustment for Mexican American adolescents: A prospective examination of the benefits of culturally related values. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:893–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. Annals of Child Development. 1989;6:187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Larson J. Peer relationships in adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 74–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, García-Coll C. Latino fathers: Uncharted territory in need of much exploration. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of father in child development. 4. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 98–120. [Google Scholar]

- Case MH, Robinson WL. Interventions with ethnic minority populations: The legacy and promise of community psychology. In: Bernal G, Trimble JE, Burlew AK, Leong FTL, editors. Handbook of racial and ethnic minority psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 573–590. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth D, Sandler IN. Multi-rater measurement of competence in children of divorce. Paper presented at the biennial conference of the Society for Community Research and Action; Williams, VA. Jun, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Conley AM. Patterns of motivation beliefs: Combining achievement goal and expectancy-value perspectives. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2012;104:32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MY, Updegraff KA, Roosa MW, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Perceived Discrimination and Mexican-origin Youth Adjustment: The Moderating Roles of Mothers’ and Fathers’ Cultural Orientations and Values. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2011;40:125–139. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9467-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Roeser RW. Schools as developmental contexts. In: Adams GR, Berzonsky MD, editors. Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2003. pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Flores E, Tschann JM, Dimas JM, Pasch LA, de Groat CL. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and health risk behaviors among Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57:264–273. doi: 10.1037/a0020026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll CG, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, García HV, McAdoo HP. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher L. A step-by-step approach to using SAS for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DJ, Macartney S, Blanchard VL, Denton NA. Mexican-origin children in the United States: Language, family circumstances, and public policy. In: Landale NS, McHale S, Booth A, editors. Growing up Hispanic: Health and Development of Children of Immigrants. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2010. pp. 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, Lynch ME. The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen AC, editors. Girls at puberty: Biological and psychological perspectives. New York: Plenum; 1983. pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Zupan BA. Assessment of antisocial behavior and children and adolescents. In: Stoff DM, Breiling J, Maser JD, editors. Handbook of antisocial behavior. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. pp. 36–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MF, Barth JM, Powell N, Lochman JE. Classroom contextual effects of race on children’s peer nominations. Child Development. 2006;77:1325–1337. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SM, Brown JL, Hoglund WLG, Aber JL. A school-randomized clinical trial of an integrated social–emotional learning and literacy intervention: Impacts after 1 school year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:829–842. doi: 10.1037/a0021383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. The Guilford Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Bernal MB, Garza CA, Cota MK, Ocampo KA. Family socialization and the ethnic identity of Mexican American children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1993;24:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales NA, Ettekal I, Jaconis M, Boyd BM. The Socialization of Culturally Related Values in Mexican American Families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Wood PA, Hough RL. The acculturation gap-distress hypothesis among high-risk Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:367–375. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GH, Judd CM. Statistical difficulties in detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:376–390. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgley C, Maehr ML, Urdan T. Patterns of adaptive learning survey (PALS) Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor AJ. The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6:295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda L, Navarro RL, Morales A. The role of la familia on Mexican American men’s college persistence intentions. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2011;12:216–229. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda L, Piña-Watson B, Castillo LG, Castillo R, Khan N, Leigh J. Acculturation, enculturation, ethnic identity, and conscientiousness as predictors of Latino boys’ and girls’ career decision self-efficacy. Journal of Career Development. 2011;39:208–228. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, Widaman KF. Economic stress, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American families. Child Development. 2004;75:1632–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Center. Pew Hispanic Center Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: 2004. Latino teens staying in high school: A challenge for all generations. Released January, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RA, Brown SP. On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2005;90:175–181. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. A three-stage model of ethnic identity development. In: Knight GP, Bernal ME, editors. Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1993. pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Postmes T, Branscombe NR. Influence of long-term racial environment composition on subjective well-being in African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:735–751. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.3.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, Chao RK, Cross WE, Hughes D, Nelson-LeGall S, Aboud FE, Contreras-Grau CJ, Hudley C, Liben LS, Vietze DL. Race, ethnicity, and culture in child development: Contemporary research and future directions. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1129–1141. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen YR. Ethnocultural differences in prevalence of adolescent depression. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:95–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1024649925737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Roberts RE. The impact of multiple dimensions of ethnic identity on discrimination and adolescents’ self-esteem. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33:2288–2305. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Liu FF, Torres M, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Saenz D. Sampling and recruitment in studies of cultural influences on adjustment: A case study with Mexican Americans. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:293–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review. 1994;28:748–794. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Jarvis LH. Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of American Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;3991:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Yip T. School and neighborhood contexts, perceptions of racial discrimination, and psychological well-being among African American adolescents. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2009;38:153–163. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9356-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supple AJ, Ghazarian SR, Frabutt JM, Plunkett SW, Sands T. Contextual influences on Latino adolescent ethnic identity and academic outcomes. Child Development. 2006;77:1427–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Spencer SJ, Aronson J. Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 34. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 379–440. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, Cameron R, Herrero-Taylor T, Davis G. Development of the teenager experience of the racial socialization scale: Correlates of race-related socialization frequency from the perspective of Black youth. Journal of Black Psychology. 2002;28:84–106. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, McNeil JD, Herrero-Taylor T. Influence of perceived neighborhood diversity and racism experience on the racial socialization of black youth. Journal of Black Psychology. 2005;31:273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor ZE, Widaman KF, Robins RW, Jochem R, Early DR, Conger RD. Dispositional optimism: A psychological resource for Mexican-origin mothers experiencing economic stress. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:133–139. doi: 10.1037/a0026755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusty J, Thompson B, Petrocelli JV. Practical guide to implementing the requirement of reporting effect size in quantitative research in the Journal of Counseling & Development. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2004;82:107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ. Ethnic Identity. In: Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, Vignoles VL, editors. Handbook of Identity Theory and Research. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 791–810. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ. Ethnic identity and self-esteem: Examining the role of social context. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Alfaro EC, Bámaca MY, Guimond AB. The central role of family socialization in Latino adolescents’ cultural orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Fine MA. Examining ethnic identity among Mexican-origin adolescents living in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26:36–59. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales-Backen MA, Guimond AB. Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity: Is there a developmental progression and does growth in ethnic identity predict growth in self-esteem? Child Development. 2009;80:391–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Guimond A. A Longitudinal Examination of Parenting Behaviors and Perceived Discrimination Predicting Latino Adolescents’ Ethnic Identity. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:636–650. doi: 10.1037/a0019376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Vargas-Chanes D, Garcia CD, Gonzales-Backen M. An examination of Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity, coping with discrimination, and self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28:16–50. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, Bámaca-Gómez MY. Developing the Ethnic Identity Scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2004;4:9–38. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Facts for features: Cinco de Mayo. 2011 Retrieved on June 3, 2011 from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/pdf/cb11ff-09_cinco.pdf.

- Wentzel KR, Baker S, Russell S. Peer relationships and positive adjustment at school. In: Gilman R, Huebner ES, Furlong MJ, editors. Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis; 2009. pp. 229–243. [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Roosa MW. Neighborhood contexts, fathers, and Mexican American young adolescents’ internalizing symptoms. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:152–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]