Abstract

Many studies have investigated the neurodevelopmental effects of prenatal and early childhood exposures to organophosphate (OP) pesticides among children, but they have not been collectively evaluated. The aim of the present article is to synthesize reported evidence over the last decade on OP exposure and neurodevelopmental effects in children. The Data Sources were PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCO, SciVerse Scopus, SpringerLink, SciELO and DOAJ. The eligibility criteria considered were studies assessing exposure to OP pesticides and neurodevelopmental effects in children from birth to 18 years of age, published between 2002 and 2012 in English or Spanish. Twenty-seven articles met the eligibility criteria. Studies were rated for evidential consideration as high, intermediate, or low based upon the study design, number of participants, exposure measurement, and neurodevelopmental measures. All but one of the 27 studies evaluated showed some negative effects of pesticides on neurobehavioral development. A positive dose–response relationship between OP exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes was found in all but one of the 12 studies that assessed dose–response. In the ten longitudinal studies that assessed prenatal exposure to OPs, cognitive deficits (related to working memory) were found in children at age 7 years, behavioral deficits (related to attention) seen mainly in toddlers, and motor deficits (abnormal reflexes) seen mainly in neonates. No meta-analysis was possible due to different measurements of exposure assessment and outcomes. Eleven studies (all longitudinal) were rated high, 14 studies were rated intermediate, and two studies were rated low. Evidence of neurological deficits associated with exposure to OP pesticides in children is growing. The studies reviewed collectively support the hypothesis that exposure to OP pesticides induces neurotoxic effects. Further research is needed to understand effects associated with exposure in critical windows of development.

Keywords: Environmental exposure, Organophosphate pesticides, Neurotoxicant, Neurodevelopment, Children, Health

1. Introduction

Organophosphate (OP) pesticides are a group of chemical compounds used for the control and elimination of insects in agriculture, and in some instances for residential or industrial applications. OP pesticides act as acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors, which prevent the breakdown of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, increasing both its concentration and duration of action in the body.

Exposures to OP pesticides can be toxic to humans and animals (Levine, 2007; Tadeo et al., 2008). During development, neurologic effects of OP exposure, even at low levels, may be detrimental because neurotransmitters, including acetylcholine, play essential roles in the cellular and architectural development of the brain (Barr et al., 2006). Excessive exposure in humans results in overexcitation of muscarinic and nicotinic receptors of the nervous system, inducing an over-accumulation of this neurotransmitter in the cholinergic synapses due to phosphorylation of the active cholinesterase molecule site. This effect can result in a variety of symptoms including salivation, nausea, vomiting, lacrimation, seizures and ultimately death (Costa, 2006).

Below we summarize data on routes of exposure, metabolism, and biomarkers for OP pesticides, and present the motivation for our review.

1.1. Routes of exposure

Humans may be exposed to OP pesticides through a variety of pathways including working on or living in close proximity to a farm that applies OP pesticides, home or industrial use of OP pesticides, inhalation or non-dietary ingestion of OP pesticide-laden dust, and consumption of produce containing OP pesticide residues (Curwin et al., 2005, 2007; Lu et al., 2004, 2008; Muñoz-Quezada et al., 2012; Naeher et al., 2010; Rodríguez et al., 2006; Valcke et al., 2006; Vida and Moretto, 2007).

For children, dietary exposure of OP pesticides is believed to be the predominant exposure pathway. However, a decade ago, exposure from residential use of OP pesticides was also found to be a significant exposure pathway (Whyatt et al., 2003). In addition, para-occupational exposure, i.e., exposure caused by contact with an occupationally exposed person or items that person has come in contact with such as clothing or surfaces, continues to be an important exposure pathway in children or spouses of farmers or farmworkers (Vida and Moretto, 2007; Rodríguez et al., 2006; Valcke et al., 2006; Curl et al., 2002; Fenske et al., 2002).

1.2. Metabolism

After exposure, OP pesticides may be metabolized to their more toxic oxon form, which can react with AChE, releasing its pesticide-specific metabolite. If the bound AChE ages, that is, if the adducted pesticide loses its carbon sidechains, the AChE becomes irreversibly bound, which is most often the case. If an OP pesticide does not bind to AChE, it may be enzymatically hydrolyzed through paraoxonase (PON), or spontaneously hydrolyzed to form pesticide-specific metabolites and non-specific diaklyphosphate (DAP) metabolites. These metabolites or their glucuronide- or sulfate-bound conjugates are excreted primarily in the urine. The half-life of OP pesticides in the body varies for each pesticide but is in the range of 24–48 h. A small portion of some of these pesticides is also believed to be sequestered in lipid stores of the body (Bakke and Price, 1976).

1.3. Biomarkers of exposure

OP pesticide exposure can be assessed via questionnaires, environmental measurements, and biomonitoring, the latter of which is increasingly common. Biomonitoring measurements used to assess OP pesticide exposure include AChE activity screening, measurement of specific and non-specific urinary metabolites, and measurement of the parent pesticide in blood (Barr et al., 2006; CDC, 2009; Duggan et al., 2003; Sudakin and Stone, 2011; Wessels et al., 2003). Blood pesticide measurements provide unequivocal evidence of exposure but are often difficult to obtain because of the biological reactivity of the pesticides. It is best to analyze samples soon after collection to minimize reaction/degradation and soon after exposure occurs, the timing of which is typically not known. Furthermore, the levels found in blood are typically three orders of magnitude lower than urinary metabolite levels, which additionally complicates their measurement (Barr et al., 1999).

The most widely used biologically based exposure assessment involves measuring generic urinary DAP metabolites, pesticide-specific metabolites such as 3,5,6-trichloropyridinol (metabolite of chlorpyrifos and chlorpyrifos-methyl), malathion dicarboxylic acid (metabolite of malathion), 2-isopropyl-4-methyl-6 hydroxypyrimidine (metabolite of diazinon) or urinary soluble pesticides such as methamidaphos, acephate and dimethoate (Barr et al., 2006; CDC, 2009, 2012). DAP metabolites include dimethyl phosphate (DMP), dimethylthiophosphate (DMTP), dimethyldithiophosphate (DMDTP), diethylphosphate (DEP), diethylthiophosphate (DETP), and diethyldithiophosphate (DEDTP). Each of these metabolites corresponds to one or more OP pesticides, e.g., in the case of the DEP metabolite, it corresponds to chlorpyrifos, disulfoton or diazinon pesticides (see Table 1), (Barr et al., 2006; CDC, 2009). The measurement of urinary DAP metabolites or pesticide-specific metabolites represents exposure to their preformed metabolites in the environment as well as to the parent pesticide, so it likely overestimates exposure. Regardless, these measurements, in particular the DAP metabolite measurements, remain one of the most widely used OP pesticide exposure assessment tools.

Table 1.

Widely used organophosphate pesticides (OP) and their urinary dialkylphosphate metabolites.

| OP pesticide | DMP | DMTP | DMDTP | DEP | DETP | DEDTP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azinphos-methyl | X | X | X | |||

| Chlorpyrifos | X | X | ||||

| Chlorpyrifos-methyl | X | X | ||||

| Disulfoton | X | X | X | |||

| Diazinon | X | X | ||||

| Fenitrothion | X | X | X | |||

| Malathion | X | X | X | |||

| Methidathion | X | X | X | |||

| Phosmet | X |

DMP = dimethylphosphate; DMTP = dimethylthiophosphate; DMDTP = dimethyl-dithiophosphate; DEP = diethylphosphat; DETP = dimethylthiophosphate; DEDTP = diethyldithiophosphate.

1.4. Biomarkers of susceptibility

In addition to biomarkers of exposure, biomarkers of susceptibility have been measured and have been used to assist in evaluating the association between exposure to OP pesticides and neurodevelopment (Eskenazi et al., 2010). The biomarker of susceptibility studied for OP exposures is PON1, the gene responsible for transcribing PON, has a polymorphism at amino acid 192 (R → Q) that can alter expression and activity of PON, thus altering a person’s ability to detoxify OP pesticides (González et al., 2012; Huen et al., 2012). Individuals with wildtype PON1 (RR) have almost three times the PON activity as those with the Q/Q variant and about 1.5 times more activity than the R/Q variant (Rojas-García et al., 2005).

1.5. Biomarkers of effect

Biomarkers are also used to assess the effects of OP exposure, although the tools available for this approach are limited. Red blood cell AChE and plasma butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) activities are used as biomarkers in clinical and occupational settings (Farahat et al., 2011). The most commonly used biomarker of effect of OP pesticide exposure is a functional decrease in AChE activity, primarily to monitor acute exposures in farmers or farmworkers, but this requires baseline assessment (pre-exposure), and is believed to be sensitive only to high exposures. In addition, even though AChE activity is an appropriate measure of acute effects, this measure may not be an informative biomarker of neurodevelopmental effects in children, because most of these are believed to result from interference of dopaminergic or serotonergic pathways during development at exposure levels that do not cause appreciable AChE inhibition (Aldridge et al., 2005a,b).

1.6. The current review

In the last decade, many studies have reported on neurobehavioral effects associated with OP pesticide exposure in children (Alavanja et al., 2004; Bradman and Whyatt, 2005; Eskenazi et al., 2008; Garry et al., 2004; Jurewicz and Hanke, 2008; Rosas and Eskenazi, 2008). However, to date, there has been no systematic review of this literature. Compiling all of these results in a systematic way allows for an assessment of the current state of knowledge and to identify research gaps.

Our aim with this study was to systematically review and synthesize findings from studies that evaluated OP pesticide exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children. We excluded studies published prior to 2002 because many of these lack current exposure assessments or neurological tests that are common to the more recent studies (Jurewicz & Hanke, 2008). We restricted our review to children (including those exposed in utero) because our current understanding of the potential modes of action involves different pathways than acute toxicity in adults (Aldridge et al., 2005a,b).

2. Methods

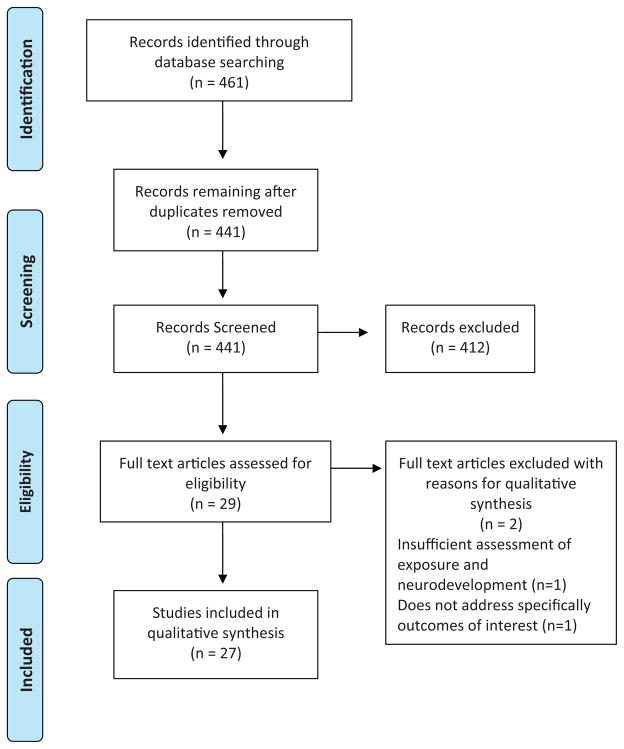

Epidemiological studies that included OP pesticide exposure assessment and neurobehavioral testing were identified through literature searches in PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCO, SciVerse Scopus, SpringerLink, SciELO, and DOAJ databases. Search terms included: “organophosphate AND pesticides AND children”; “pesticides AND children AND neurobehavioral”; “organophosphate pesticides AND children AND neurobehavioral”; and “chlorpyrifos AND pesticides AND neurodevelopment”. Criteria for inclusion in the review included: 1) exposure assessment for OP pesticides; (2) neurological effects assessed; (3) participants 0–18 years; and (4) studies published from 2002 to 2012. The languages of publication considered were English and Spanish. We identified a total of 461 articles with our search terms, after excluding duplicate articles we screened 441 articles, from which 29 met our eligibility criteria and finally only 27 articles were included in this review (Fig. 1). From each study, we extracted information about the population characteristics, study design, instruments used for measuring effects (Table 2) and exposure, results, and confounders controlled. Each study was assessed for its individual strengths and was given a rating based upon: (1) exposure assessment methods used; (2) neurodevelopmental assessments used; (3) study design; (4) sample size; and (5) whether important confounders were appropriately controlled. To give the rating to each study, it was assigned a score of 0 to 2 for each of 5 parameters. The characteristics of these five parameters and the ranking scheme are described in more detail in Table 3. Studies were classified into three mutually exclusive categories: Low (0–2 points), Intermediate (3–7 points), and High (8–10 points). The studies rated in the High category were given more consideration in our conclusions than those in the other two categories.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of publication selection process.

Table 2.

Neurodevelopmental assessment instruments used to study the effects of organophosphate pesticides in children and adolescents.

| Assessment instrument | Specific age rangea | Effects measured | Studies that used the instrument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized, well-validated diagnostic tests | |||

| Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (BNBAS) | 0–2 months | B, M | Engel et al. (2007), Young et al. (2005) |

| Bayley Scales of infant development (BSID-II) | 1–42 months | C, B, M | Engel et al. (2011), Eskenazi et al. (2010), Eskenazi et al. (2007), Rauh et al., 2006 |

| Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment (NEPSY II) | 3–16 years 11 months | B | Marks et al. (2010)b |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, fourth edition (WISC-IV) | 6–16 years 11 months | C(IQ) | Rauh et al. (2012), Bouchard et al. (2011), Engel et al. (2011), Rauh et al. (2011) |

| Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, third edition (WPPSI-III) | 2–7 years | C(IQ) | Engel et al. (2011) |

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) | 6–89 years | C | Lizardi et al. (2008) |

| Neurobiologically based markers of development | |||

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | No age limits | Bm | Rauh et al. (2012) |

| Screening tests | |||

| Conners’ Kiddie Continuos Performance Test (K-CPT) | 4–5 years | B | Harari et al. (2010); Marks et al. (2010) |

| Raven’ Colored Progressive Matrices | 5–11 years | C | Harari et al. (2010) |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) Forms A & B | Children’s version: 9–14 yearsc | M | Abdel Rasoul et al. (2008), Lizardi et al. (2008) |

| Benton Visual Retention Test(BVRT) | 8–64 years | S | Abdel Rasoul et al. (2008) |

| Checklists, interviews or questionnaires | |||

| Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) | 4–60 months | C, B, M | Handal et al. (2008); Handal et al. (2007a), Handal et al. (2007b) |

| Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) | Preschool version: 18 months – 5 years old. School-age version: 6–18 years |

B | Eskenazi et al. (2010), Marks et al. (2010), Eskenazi et al. (2007), Rauh et al. (2006) |

| Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV (DISC IV) from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) | Parent of children 6–17 years and children 9–17 years | B | Bouchard et al. (2010) |

| The Teacher Report Form (TRF) | 6–18 years | B | Lizardi et al. (2008) |

| Outdated versions of well-validated diagnostic tests | |||

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, revised edition (WISC-R) | 6–16 years 11 months | C(IQ) | Harari et al. (2010)b, Kofman et al. (2006)b, Grandjean et al. (2006)b, Martos Mula et al. (2005)b |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, third edition (WISC-III v.Ch) | 6–16 years 11 months | C(IQ) | Muñoz et al. (2011), Lizardi et al. (2008)b |

| Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, revised (WPPSI-R) | 3–7 years 3 months | C(IQ) | Dahlgren et al. (2004) |

| Wechsler adult intelligent scale (WAIS) | 16–74 years 11 months | C(IQ) | Abdel Rasoul et al. (2008)b |

| Stanford Binet Intelligence Scale | 2–23 years | C(IQ) | Harari et al. (2010)b, Grandjean et al. (2006)b |

| A Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment (NEPSY) | 3–12 years | B | Kofman et al. (2006)b, Dahlgren et al. (2004)b |

| Not widely used | |||

| Behavioral Assessment and Research System (BARS)d | 4–91 years | C, B, S, M | Eckerman et al. (2007), Rohlman et al. (2007), Rohlman et al. (2005) |

| Gessell Developmental Schedules, Chinese adaptation (GDS) | 0–6 years | C, B, M | Guodong et al. (2012) |

| Pediatric Environmental Neurobehavioral Test Battery (PENTB)d | Informant-based version: <4 years Performance-based version: >4 years |

C, B, M | Rohlman et al. (2005)b, Ruckart et al. (2004) |

| Santa Ana Form Board Test | Not specified | M | Grandjean et al. (2006) |

| The Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration, fourth edition (VMI) | 3–8 years | M | Handal et al. (2007b) |

| Finger Tapping test | Not specifiedc | M | Harari et al. (2010) |

| Digit Vigilance Test (DVT) of Lewis | 20–80 yearsc | B | Martos Mula et al. (2005) |

C = Cognitive; B = Behavioral; S = Sensory; M = Motor; Bm = Brain morphology; IQ = Intelligence quotient.

Age for which the test was designed and eventually validated.

Administered only selected sections of the full test or battery.

Designed and used mainly for the assessment of adult populations.

Batteries composed of several different individual tests. For more detailed information on PENTB see Zeitz et al. (2002), and for BARS see Rohlman et al. (2003).

Table 3.

Definition of rating scores used to assess the study strength.

| Parameter | Score assigned

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Exposure assessment | Specific biomarkers (e.g., blood chlorpyrifos) | General biomarkers (e.g., DAP metabolites) | Ecological dataa; Hospital records of intoxication or poisoning |

| Neurodevelopmental assessmentb | Standardized, well-validated tests for diagnostic or neurobiologically based markers of development | Screening tests, interviews, checklists or questionnaires. Older versions of well validated tests. Not widely used tests in neurodevelopmental assessment | Selected sections of full test batteries |

| Study design | Longitudinal, exposures precede outcome | Case control | Cross-sectional, case study |

| Sample size | >200 | ≥50 | <50 |

| Confounder control | Good control for important confoundersc and standard variables | Standard variables controlled in analysesd | Not considered |

Categories of rating: 0–2 = low rating, 3–7 = intermediate rating, 8–10 = high rating.

Ecological data: Exposure assumed by the proximity to places where pesticides were applied or in children or adolescents that worked in farms.

For specific characteristics of the neurodevelopmental assessment instruments see Table 2.

Important confounders to control in this class of studies could be: Parental intelligence, quality of the home environment, potential factors on the causal pathway (birth weight, gestational age, abnormal reflexes), other suspected neuro-toxicants (i.e., PCBs, lead, and DDT), other high-level exposures in the population (i.e., β-hexachlorocyclohexane and hexa-chlorobenzene), exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS).

Standard variables considered: age, sex, education, income, race/ethnicity.

The main neurodevelopmental effects observed in children and adolescents exposed to OP pesticides were classified in five categories: (1) Cognitive, which includes IQ, mental and psychological development, memory, language and reasoning; (2) Behavioral, which includes attention function problems, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), adaptive behavior, pervasive development disorder, inhibitory control and social development; (3) Sensory, which includes auditory and visual stimulation; (4) Motor, which includes motor skills; and (5) Morphology, which includes physical changes measured in the brain.

3. Results

Table 4 summarizes the design, sample characteristics, exposure assessment techniques outcome measures, and ratings of the 27 studies included in our review. All studies except one cross-sectional study in China (Guodong et al., 2012) provided some evidence that exposure to OP pesticides was a risk factor for poor neurodevelopment, with the strongest effects stemming from prenatal exposures. Eleven studies (all longitudinal) were rated High, 14 studies were rated Intermediate, and two studies were rated Low. A positive dose–response relationship (i.e., increased effect with higher levels of exposure) between OP exposure and neurodevelopmental issues was found in 11 of the 12 studies that evaluated it.

Table 4.

Characteristics of published studies evaluating neurologic effects from prenatal or childhood exposures to organophosphate (OP) pesticides. The three US birth cohorts are listed first (study/year) followed by other studies in chronologic/alphabetic order.

| Author/cohort | Exposure assessment | Sample sizeb | Age | Neurodevelopmental assessment | Study design | Dose–response | Study rating (score) | OP pesticide(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young et al. (2005) (CHAMACOS, CA, USA) | Repeated (2) maternal urinary DAPs | 381 | Neonates | BNBAS | CL | Y | High (8) | OP class exposure |

| Eskenazi et al. (2007) (CHAMACOS, CA, USA) | Repeated (2) maternal urinary DAPs, MDA, TCPY; children urinary DAPs | 396 395 372 |

6 mo 1 yr 2 yrs |

BSID-II (MDI/PDI); CBCL | CL | Y | High (10) | OP class exposure, malathion, chlorpyrifos via occupational/para-occupational |

| Eskenazi et al. (2010) (CHAMACOS, CA, USA) | Repeated (2) maternal and 2 year old urinary DAPs, PON1 genotype/activity in maternal cord | 353 | 2 yrs | BSID-II (MDI/PDI); CBCL | CL | Y | High (9) | OP class exposure, malathion, chlorpyrifos via occupational/para-occupational |

| Marks et al. (2010) (CHAMACOS, CA, USA) | Repeated (2) maternal urinary DAPs | 331 323 |

3.5 yrs 5 yrs |

CBCL; NEPSY-IIg K-CPT |

CL | Y | High (8) | OP class exposure, malathion, chlorpyrifos via occupational/para-occupational |

| Bouchard et al. (2011) (CHAMACOS, CA, USA) | Repeated (2) maternal urinary DAPs | 329 | 7 yrs | WISC-IV | CL | Y | High (9) | OP class exposure via occupational/para-occupational |

| Rauh et al. (2006) (Columbia, NY, USA) | Umbilical cord CPF | 254 | 1–3 yrs | BSID-II, CBCL | CL | Y | High (10) | CPF via indoor air |

| Rauh et al. (2011) (Columbia, NY, USA) | Umbilical cord CPF | 265 | 7 yrs | WISC-IV | CL | Y | High (10) | CPF |

| Rauh et al. (2012) (Columbia, NY, USA) | Umbilical cord CPF | 40 | 6–11 yrs | MRI, WISC-IV | CL | Y | High (8) | CPF via indoor air |

| Engel et al. (2007) (Mt. Sinai, NY, USA) | Maternal DAPs | 311 | Neonates | BNBAS | CL | Y | High (8) | OP class exposure |

| Engel et al. (2011) (Mt. Sinai, NY, USA) | Maternal DAPs, PON activity, genotype | 200 276 169 |

1 yr 2 yrs 6–9 yrs |

BSID-II (MDI/PDI); WPPSI-III; WISC IV | CL | Y | High (9) | OP class exposure |

| Dahlgren et al. (2004) (Family case study; CA, USA) | Air, wipe DZN | 5 | 5 mos-11 yrs | WPPSI-R NEPSY Blockg | CS | n/a | Low (0) | DZN |

| Rohlman et al. (2005) (OR and NC, USA) | Parent’s occupationa | 43/78 | 4–5 yrs | BARS, PENTBg | C | n/a | Intermediate (3) | OP pesticide not specified |

| Ruckart et al. (2004) (Superfund sites, USA) | Urinary PNP; MP surface wipes | 279 | <6 yrs | PENTB | CL | n/a | High (8) | MP from chronic high level residential exposures |

| Martos Mula et al. (2005) (Jujuy, Argentina) | Proximity to usea | 64/87 | 11–16 yrs | WISC-Rg, DVT | C | n/a | Low (1) | OP pesticide not specified |

| Eckerman et al. (2007) (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) | Index score derived from a questionnaire | 66 | 10–18 yrs | BARS | C | n/a | Intermediate (3) | OP pesticide not specified |

| Grandjean et al. (2006) (Quito, Ecuador) | Maternal occupation; Child urinary DAPs, AChE activity | 37/72 | 6–8 yrs | WISC-Rg; Stanford-Binetg; Santa Ana Form Board | C | Y (reaction time only) | Intermediate (4) | OP class exposure |

| Kofman et al. (2006) (poisonings occurring <3 yrs age in Israel) | Hospital record abstraction of symptoms | 9/52 | 9 years | NEPSYg, WISC-Rg | CL | n/a | Intermediate (3) | OP class exposure |

| Rohlman et al. (2007) (Oregón, USA) | Occupationa | 50/77c | 12–60 years | BARS | C | n/a | Intermediate (3) | OP pesticide not specified |

| Handal et al. (2007a) (Ecuador) | Proximity to usea | 154/283 | 3–61 mos | ASQ | C | n/a | Intermediate (5) | OP pesticide not specified |

| Handal et al. (2007b) (Ecuador) | Proximity to use, parent’s occupation, child activitiesa | 142 | 24–61 mos | ASQ, VMI | C | n/a | Intermediate (4) | OP pesticide not specified |

| Lizardi et al. (2008) (Hispanic agricultural children in AZ, USA) | Child urinary DAPs | 48 | 5–8 yrs | WISC-IIIg, WCST, CMS, TMT(A&B), CBCL, TRF | C | n/a | Intermediate (3) | Dimethyl-OPs |

| Abdel Rasoul et al. (2008) (Menoufia, Egypt) | Child’s occupation, AChE | 50/100 | 9–18 yrs | WAISg, TMT(A&B), BVRT | C | n/a | Intermediate (3) | OP and carbamate class exposure |

| Handal et al. (2008) (Ecuador) | Maternal occupation during pregnancya | 121 | 3–24 mos | ASQ | C | n/a | Intermediate (4) | OP pesticide not specified |

| Bouchard et al. (2010) (NHANES 2000–2004, USA) | Urinary DAPs | 1139 | 8–15 yrs | DISC-IV from DSM-IV | C | Y | Intermediate (6) | OP class exposure |

| Harari et al. (2010) (Quito, Ecuador) | Maternal occupation; Child urinary DAPs, AChE activity | 35/87d 23/87e 22/87f |

6–8 yrs | WISC-Rg; Stanford-Binetg; Raven’s colored progressive matrices, Santa Ana Form Board, FTT | C | n/a | Intermediate (4) | OP class exposure |

| Muñoz et al. (2011) (Chile) | Urinary DAPs | 25 | 6–16 yrs | WISC-III | C | n/a | Intermediate (3) | OP class exposure |

| Guodong et al. (2012) (Shanghai, China) | Child urinary DAPs | 301 | 2 yrs | GDS | C | N | Intermediate (6) | OP class exposure |

Exposure assessment: AChE = acetylcholinesterase; CPF = chlorpyrifos; DAPs = dialkylphosphate metabolites of organophosphate insecticides; DZN = diazinon; MDA = malathion dicarboxylic acid (metabolite of malathion); MP = methyl parathion; PNP = para-nitrophenol (metabolite of methyl parathion); PON1 = paraoxonase; TCPY = 3,5,6-trichloropyridinol (metabolite of chlorpyrifos and chlorpyrifos methyl).

There is no certainty of exposure to OP pesticides specifically, and it could be assumed only as likely or potential.

Sample size

The sample number includes either the full population of the study or the exposed population/total population.

Exposed/total population only considering adolescent partipants.

Exposed during pregnancy via maternal occupation

Indirect exposure from paternal work

Current exposure irrespective of prenatal exposure.

Neurodevelopmental Assessment: For descriptions, see Table 2

Administered only selected sections of the full test or battery

Study design: C = cross-sectional; CL = cohort (longitudinal); CS = case study (no controls).

Dose/response: Y = Yes, N = No, n/a = non applicable (dose/response was not evaluated). Study Rating (see Table 3 for details): Low (0–2); Intermediate (3–7); High (8–10).

OP Pesticide(s): OP class exposure = Studies in which the assessment of exposure was made through biomarkers of OP residues that are not able to differentiate the specific type of pesticide used (e.g., DAPs metabolites).

OP pesticide not specified = Studies in which there were no measuring of metabolites or biomarkers, and the information was obtained only through a questionnaire, the occupation or the location of communities.

The majority of studies (N = 16) were conducted in the United States (Bouchard et al., 2010, 2011; Dahlgren et al., 2004; Engel et al., 2007, 2011; Eskenazi et al., 2007, 2010; Lizardi et al., 2008; Marks et al., 2010; Rauh et al., 2006, 2011, 2012; Rohlman et al., 2005, 2007; Ruckart et al., 2004; Young et al., 2005), but studies were also conducted in Ecuador (N = 5) (Grandjean et al., 2006; Handal et al., 2007a, 2007b, 2008; Harari et al., 2010), Chile (N = 1) (Muñoz et al., 2011), Egypt (N = 1) (Abdel Rasoul et al., 2008), Israel (N = 1) (Kofman et al., 2006), Argentina (N = 1) (Martos Mula et al., 2005), Brazil (N = 1) (Eckerman et al., 2007) and China (N = 1) (Guodong et al., 2012). Exposure scenarios included occupational (N = 3), residential (N = 3), poisonings (N = 1), para-occupational (N = 11) and background environmental (N = 9). The OP pesticide exposure assessment varied among studies, and ranged from biomarker-based exposure assessments to questionnaire data or screening of hospital records.

A summary of the neurodevelopmental effects observed across studies is shown in Table 5. Cognitive effects were evaluated in 23 studies, behavioral effects in 19, sensory effects in 8, motor effects in 18, and one study used a MRI to evaluate morphological effects. With regards to cognitive performance, the Wechsler scales are indicated by the literature as the most reliable and valid to assess intelligence in children (Brunner et al., 2011; Gass and Curiel, 2011; Kanaya and Ceci, 2012; San Miguel Montes et al., 2010). The Wechsler scale mostly used was the WISC, which was created to assess the intelligence of children between 6 and 16 years old. Six studies used this standard instrument in its full version (Bouchard et al., 2011; Engel et al., 2011; Grandjean et al., 2006; Muñoz et al., 2011; Rauh et al., 2012, 2011). Other studies used only some subtests from that scale to assess specific cognitive functions or administered abbreviated forms of the instrument (Grandjean et al., 2006; Harari et al., 2010; Kofman et al., 2006; Lizardi et al., 2008; Martos Mula et al., 2005; Abdel Rasoul et al., 2008).

Table 5.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes of organophosphate pesticide exposure studies listed in Table 4.

| Author/cohort | Cognitive | Behavioral | Sensory | Motor | Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young et al. (2005) (CHAMACOS, CA, USA) | n/a | No effect | n/a | ↑ Abnormal reflexes | n/a |

| Eskenazi et al. (2007) (CHAMACOS, CA, USA) | 3.5 point decrease in MDI with 10-fold increase in DAPs @ 24 months but not at other ages | 2-Fold increase in risk of PDD with each 10-fold increase in DAPs | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Eskenazi et al. (2010) (CHAMACOS, CA, USA) | ↓ MDI score with PON1 variant | ↑ PDD symptoms with ↓ PON1 activity | n/a | No effect | n/a |

| Marks et al. (2010) (CHAMACOS, CA, USA) | n/a | ↑ Attention problems, ADHD | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Bouchard et al. (2011) (CHAMACOS, CA, USA) | 7 IQ pt decrease between lowest and highest quintile of exposure @ 7 years (changes seen in working memory, processing speed, verbal comprehension and perceptual reasoning) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Rauh et al. (2006) (Columbia, NY, USA) | 3.3 pt ↓ in MDI score | ↑ Risk of attention symptom, ADHD, PDD problems | n/a | 6.5 pt ↓ in PDI score | n/a |

| Rauh et al. (2011) (Columbia, NY, USA) | 0.4–0.8 pt and 0.2–0.4 decrease in Working Memory score and IQ with 1 pg/g increase in CPF | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Rauh et al. (2012) (Columbia, NY, USA) | IQ × exposure interaction related to ↑ surface measures of brain | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↑ Brain areas associated with cognition, behavior, language, reward, emotion and inhibitor control likely related to swelling from neuronal damages IQ x exposure interaction related to ↑ surface measures of brain |

| Engel et al. (2007) (Mt. Sinai, NY, USA) | n/a | No effect | n/a | 2.24× ↑ abnormal reflexes | n/a |

| Engel et al. (2011) (Mt. Sinai, NY, USA) | 3.3 and 2.1 point decrease in MDI with 10-fold increase in DAPs @12 (nonwhites only) and 24 months; no affect on PDI; decreased perceptual reasoning | n/a | n/a | No effect | n/a |

| Rohlman et al. (2005) (OR and NC, USA) | No effect | No effect | No effect | ↓ Response speed and latency | n/a |

| Ruckart et al. (2004) (Superfund sites, USA) | ↓ In short term memory (inconsistent across sites) | ↓ Attention and adaptive behavior (inconsistent across sites) | n/a | ↓ Motor skills (inconsistent across sites) | n/a |

| Dahlgren et al. (2004) (Family case study; CA, USA) | Diagnosis of cognitive disorder, attention/executive dysfunction, severe expressive language disorder | n/a | ↓ Visual and auditory stimuli | Verbal articulation problems | n/a |

| Martos Mula et al. (2005) (Jujuy, Argentina) | ↓ Short term memory | No effect | ↓ Visual perception performance | n/a | n/a |

| Eckerman et al. (2007) (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) | ↓ In digit span test | ↓ selective attention | No effect | ↓ Motor speed | n/a |

| Grandjean et al. (2006) (Quito, Ecuador) | No effect | n/a | ↓ Visuospatial performance | ↑ Reaction time with ↑ DAPs | n/a |

| Kofman et al. (2006) (poisonings occurring <3 yrs age in Israel) | ↓ Verbal memory | Decreased performance on statue test (↓ inhibitory control) | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Rohlman et al. (2007) (Oregon, USA) | ↓ Complex functioning | ↓ sustained attention | No effect | ↓ Response speed | n/a |

| Handal et al. (2007a) (Ecuador) | Marginally significant ↓ in communication | ↓ Social individual skills | n/a | ↓ Fine and gross motor skills | n/a |

| Handal et al. (2007b) (Ecuador) | ↓ Problem solving skills | No effect | n/a | ↓ Fine motor skills, ↓ visual motor integration | n/a |

| Lizardi et al. (2008) (Hispanic agricultural children in AZ, USA) | ↓ In subtest performance driven by two high levels (↓ conceptual level responses, failure to maintain set, ↑ number of errors and perseverative responses). | No effect | n/a | No effect | n/a |

| Abdel Rasoul et al. (2008) (Menoufia, Egypt) | ↓ Intelligence in exposed, ↓ spatial relations, ↓ memory speed | ↓ Attention in exposed | ↓ Audio and visual memory | No effect | n/a |

| Handal et al. (2008) (Ecuador) | ↓ Communication skills | n/a | ↓ Visual accuity | ↓ Fine motor skills | |

| Bouchard et al. (2010) (NHANES 2000–2004, USA) | n/a | ↑ Hyperactive/impulsive ADHD; no differences seen in inattentive subtype or combined subtypes | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Harari et al. (2010) (Quito, Ecuador) | No effect | ↓ Attention function with DAPs | n/a | ↓ Motor speed, function with maternal occupation | n/a |

| Muñoz et al. (2011) (Chile) | ↓ Processing speed | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Guodong et al. (2012) (Shanghai, China) | No association with language score | No association with social score | n/a | No association with motor score | n/a |

ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; DAPs = dialkylphosphate metabolites of organophosphate insecticides; n/a = not applicable; MDI = mental development index; PDD = pervasive development disorder; PDI = psychomotor development index; PON1 = paraoxonase.

Eleven studies assessed neurological and behavioral symptoms associated with pesticide exposure through questionnaires or clinical history (Bouchard et al., 2010; Eskenazi et al., 2007, 2010; Handal et al., 2007a, 2007b, 2008; Lizardi et al., 2008; Marks et al., 2010; Martos Mula et al., 2005; Abdel Rasoul et al., 2008; Rauh et al., 2006).

Sensory development was assessed in only one study by a specific instrument (Abdel Rasoul et al., 2008), in three studies by the sensory subtests of Wechsler scales (Dahlgren et al., 2004; Grandjean et al., 2006; Martos Mula et al., 2005), and in three studies by the sensory subtests of the Behavioral Assessment and Research System (BARS) (Eckerman et al., 2007; Rohlman et al., 2005, 2007). Assessment of motor skills was conducted in fourteen studies administering a battery containing specific subtests for motor abilities among others that assessed other neurodevelopmental areas as well (Eckerman et al., 2007; Engel et al., 2007, 2011; Eskenazi et al., 2007, 2010; Guodong et al., 2012; Handal et al., 2007a, 2007b, 2008; Rauh et al., 2006; Rohlman et al., 2005, 2007; Ruckart et al., 2004; Young et al., 2005). In five studies the motor skills were assessed by specific instruments for that area (Abdel Rasoul et al., 2008; Grandjean et al., 2006; Handal et al., 2007b; Harari et al., 2010; Lizardi et al., 2008).

The ten studies stemming from birth cohorts were conducted by different research centers. Five of the studies reviewed here were conducted by the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS) study, based at University of California, Berkeley. In this project, investigators studied the association of pesticides and other environmental exposures on the health of pregnant women and their children in the agricultural area of Salinas Valley in North California (Bouchard et al., 2011; Marks et al., 2010; Eskenazi et al., 2007, 2010; Young et al., 2005). Three of the studies reviewed here were part of a birth cohort study conducted by the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health, evaluating the effects of prenatal exposures to ambient pollutants on birth outcomes and neurocognitive development in a cohort of mothers and newborns from low-income communities in New York City (Rauh et al., 2006, 2011, 2012). Finally, two studies reviewed here were part of a third birth cohort study conducted by the Mount Sinai Children’s Environmental Health Center in New York City. This project evaluated the impact of pesticide and PCB exposure on pregnancy outcome and child neurodevelopment in an inner-city multiethnic cohort of women recruited during pregnancy (Engel et al., 2007, 2011). While multiple studies came from the same cohorts (and all studies from the same cohort had the same exposure assessment), each reported different neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Cognitive findings were relatively consistent across the three birth cohorts. In two of those studies that assess cohort children at 7 years old was found association with working memory deficits (Bouchard et al., 2011; Rauh et al., 2011). Previously, and for the same cohorts, the authors found substantial decreases in the mental development index (MDI) scores on the Bayley Scale of Infant Development (BSID) and decrements in IQ related to OP pesticides exposures. The behavioral and motor skill findings were somewhat less consistent over the 10 birth cohort studies. With regard to attention problems, almost all the studies found positive evidence, except for those that assessed neonates with the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scales (BNBAS). In two studies from the CHAMACOS cohort (Eskenazi et al., 2007, 2010), the behavior measure was the same in both studies for the children of 2 years old (the CBLC), so it is somewhat expected that the behavioral findings reported were in the same direction, with the difference being that in one study the behavior measure was associated with DAP levels and in the other with PON1 activity. In the case of the motor findings in the birth cohort studies, both that assessed neonates found positive evidence related to abnormal reflexes. On the other hand, only one that assessed toddlers with the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID-II) found decreases in psychomotor development. In synthesis, in the 10 birth cohort studies cognitive findings related to working memory deficits were consistent for children at 7 years, the behavioral findings were more consistent for toddlers, while the motor findings were more consistent for neonates.

4. Discussion

All studies except one cross-sectional study in China (Guodong et al., 2012) provided evidence that exposure to OP pesticides was a risk factor for poor neurodevelopment, with the strongest linkages resulting from prenatal exposures. While publication bias may play a role in these results, the consistency of positive findings in 26 studies suggests that pesticides negatively affect children’s neurodevelopment. The highest rated data in this review originates from ten longitudinal studies of three birth cohorts, in which exposure was assessed prenatally via measurement of urinary dialkyl phosphates in the mothers during pregnancy or umbilical cord plasma chlorpyrifos, prior to any assessment of neurodevelopment. These longitudinal studies with dose–response data, found a positive dose–response relationship between OP exposure and most neurodevelopmental outcomes, which strengthens a presumption of causality. A positive relationship was found in all but one of the 12 studies that assessed dose–response. One caveat is that multiple neurodevelopmental endpoints within one cohort may be correlated, which would make the consistency across endpoints less striking We were unable to conduct a meta-analysis of the 27 studies reviewed primarily because the outcome measures differed between the studies, limiting their comparability. In addition, research design, method of measuring exposure and outcome, control of bias and confounding all varied greatly among studies.

Many of the studies published between 2004 and 2008 used only partial portions of neurological testing batteries, including the Stanford-Binet scale (Grandjean et al., 2006; Harari et al., 2010), WISC-R (Grandjean et al., 2006; Harari et al., 2010; Kofman et al., 2006; Martos Mula et al., 2005), the WISC-III (Lizardi et al., 2008), and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) for adolescents (Abdel Rasoul et al., 2008). Because only selected sub-tests in these batteries were used, they show only a partial quantification of the effects on cognitive development of children exposed to OP pesticides (Williams et al., 2003a). It is important to note that each sub-test in these batteries measures a cognitive skill that alone does not represent the construct of intelligence or cognitive functioning as a whole (San Miguel Montes et al., 2010) and a child’s performance in a sub-test may be altered by other extraneous variables such as anxiety, culture or education (Brunner et al., 2011; Gass and Curiel, 2011).

Several studies (Grandjean et al., 2006;Harari et al., 2010; Kofman et al., 2006; Martos Mula et al., 2005) administered older versions of the Wechsler scales (e.g., WISC-R, from the 1970s) to assess intelligence, which have shown lower reliability on both the full scale and the individual tests compared to the newer versions (Williams et al., 2003b). Given that the mis-measurement of outcome is likely to be non-differential in relation to exposure, we would expect use of the WISC-R may results in bias toward the null.

In addition to the strong weight of evidence for the neurodevelopmental impacts of OP pesticides that this systematic review reveals, it also identifies gaps in the literature and factors that should be considered in future studies:

More research is needed to improve understanding of whether repeated exposures over time or just short-term exposures during critical windows of development are related to neurological deficits.

Where possible, future studies should provide information on the specific OP pesticides the child is exposed to or the most likely pesticides, based upon usage data.

Because residential uses of many OP pesticides were phased out a decade ago, populations who are at higher risk of exposure should be evaluated, such as those children and adolescents that live near to farms, or that are exposed paraoccupational or occupationally.

Common exposure and outcome metrics would aid in comparing results across studies to better enable synthesis of future research, which would allow for a meta-analysis.

Finally, it should be noted that research in this field is critical for informing regulatory and policy decisions. For example, the U.S. Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 called for the reassessment of food tolerances for pesticides and OP pesticides were among the first to be evaluated. During this process, almost all registrations of residential applications of chlorpyrifos, diazinon and azinphos-methyl were voluntarily withdrawn. Data derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) has demonstrated that these registration eliminations and reductions in pesticide food tolerances were effective in reducing population exposure to OP pesticides (Clune et al., 2012).

5. Conclusion

The evidence obtained from this systematic review of studies points to the adverse neurodevelopmental effects of OP pesticide exposure in children, especially for cognitive, behavioral (mainly related to attention problems), and motor outcomes. This information is critical for evaluating exposure and neurological deficits for future regulatory system reviews. The research points to the need for implementation of further protection from the harmful effects of OP pesticides in children.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was funded by grants NIH Fogarty D43 TW 05746-02, USA, NIH 5R21ES015465-02, and FONIS SA10I20001 by The National Commission for Scientific and Technological Investigation (CONICYT) of the Chilean government.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdel Rasoul GM, Abou Salem ME, Mechael AA, Hendy OM, Rohlman DS, Ismail AA. Effects of occupational pesticide exposure on children applying pesticides. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29(5):833–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavanja M, Hoppin J, Kamel F. Health effects of chronic pesticide exposure: cancer and neurotoxicity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:155–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge JE, Levin ED, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Developmental exposure of rats to chlorpyrifos leads to behavioral alterations in adulthood, involving serotonergic mechanisms and resembling animal models of depression. Environ Health Perspect. 2005a;113(5):527–31. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge JE, Meyer A, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Alterations in central nervous system serotonergic and dopaminergic synaptic activity in adulthood after prenatal or neonatal chlorpyrifos exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2005b;113(8):1027–31. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakke JE, Price CE. Metabolism of OO-dimethyl-O-(3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridyl) phosphorothioate in sheep and rats and of 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol in sheep. J Environ Sci Health B. 1976;11(1):9–22. doi: 10.1080/03601237609372022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr DB, Barr JR, Driskell WJ, Hill RH, Jr, Ashley DL, Needham LL, et al. Strategies for biological monitoring of exposure for contemporary-use pesticides. Toxicol Ind Health. 1999;15(1–2):168–79. doi: 10.1191/074823399678846556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr DB, Bradman A, Freeman N, Whyatt RM, Wang RY, Naeher L, et al. Studying the relation between pesticide exposure and human development. In: Belliger DC, editor. Human developmental neurotoxicology. Nueva York: Taylor & Francis Group; 2006. pp. 253–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard MF, Bellinger DC, Wright RO, Weisskopf MG. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and urinary metabolites of organophosphate pesticides. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):e1270–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard MF, Chevrier J, Harley KG, Kogut K, Vedar M, Calderon N, et al. Prenatal exposure to organophosphate pesticides and IQ in 7-year-old children. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(8):1189–95. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradman A, Whyatt R. Characterizing exposures to nonpersistent pesticides during pregnancy and early childhood in the national children’s study: a review of monitoring and measurement methodologies. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(8):1092–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner M, Nagy G, Wilhelm O. A tutorial on hierarchically structured constructs. J Pers. 2011;80(4):796–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) Fourth national report on human exposure to environmental chemicals. Atlanta, USA: 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/pdf/FourthReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) Fourth national report on human exposure to environmental chemicals, updated tables. Atlanta, USA: 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/pdf/FourthReport_UpdatedTables_Feb2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clune AL, Ryan PB, Barr DB. Have regulatory efforts to reduce organophosphorus insecticide exposures been effective? Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(4):521–5. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa LG. Current issues in organophosphate toxicology. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;366(1–2):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curl CL, Fenske R, Kissel JC, Shirai JH, Moate TF, Griffith W, et al. Evaluation of take-home organophosphorus pesticide exposure among agricultural workers and their children. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(12):A787–92. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021100787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curwin B, Hein M, Sanderson W, Nishioka M, Reynolds S, Ward E, et al. Pesticide contamination inside farm and nonfarm homes. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2005;2(7):357–67. doi: 10.1080/15459620591001606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curwin B, Hein M, Sanderson W, Striley C, Heederik D, Kromhout H, et al. Urinary pesticide concentrations among children, mothers and fathers living in farm and non-farm households in Iowa. Ann Occup Hyg. 2007;51(1):53–65. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mel062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren JG, Takhar HS, Ruffalo CA, Zwass M. Health effects of diazinon on a family. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42(5):579–91. doi: 10.1081/clt-200026979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan A, Charnley G, Chen W, Chukwudebe A, Hawk R, Krieger RI, et al. Di-alkyl phosphate biomonitoring data: assessing cumulative exposure to organophosphate pesticides. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2003;37(3):382–95. doi: 10.1016/s0273-2300(03)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckerman DA, Gimenes LS, de Souza RC, Galvao PR, Sarcinelli PN, Chrisman JR. Age related effects of pesticide exposure on neurobehavioral performance of adolescent farm workers in Brazil. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2007;29(1):164–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel S, Berkowitz G, Barr D, Teitelbaum S, Siskind J, Meisel S. Prenatal organophosphate metabolite and organochlorine levels and performance on the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale in a multiethnic pregnancy cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;265(12):1397–404. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SM, Wetmur J, Chen J, Zhu C, Barr DB, Canfield RL, et al. Prenatal exposure to organophosphates, paraoxonase 1, and cognitive development in childhood. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(8):1182–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskenazi B, Marks AR, Bradman A, Harley K, Barr DB, Johnson C, et al. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and neurodevelopment in young Mexican-American children. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(5):792–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskenazi B, Rosas L, Marks A, Bradman A, Harley K, Holland N, et al. Pesticide toxicology and the developing brain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102(2):228–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskenazi B, Huen K, Marks A, Harley KG, Kogut K, Vedar M, et al. PON1 and neurodevelopment in children from the CHAMACOS study exposed to organophosphate pesticides in utero. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(12):1775–81. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farahat FM, Ellison CA, Bonner MR, McGarrigle BP, Crane AL, Fenske RA, et al. Biomarkers of chlorpyrifos exposure and effect in Egyptian cotton field workers. Environ Health Perspect 2011. 2011;119(6):801–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenske RA, Lu C, Barr D, Needham L. Children’s exposure to chlorpyrifos and parathion in an agricultural community in central Washington State. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(5):549–53. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garry VF. Pesticides and children. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;198(2):152–63. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass CS, Curiel RE. Test anxiety in relation to measures of cognitive and intellectual functioning. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;26(5):396–404. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acr034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez V, Huen K, Venkat S, Pratt K, Xiang P, Harley KG, et al. Cholinesterase and paraoxonase (PON1) enzyme activities in Mexican-American mothers and children from a agricultural community. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2012;22(6):641–8. doi: 10.1038/jes.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Harari R, Barr DB, Debes F. Pesticide exposure and stunding as independent predictors of neurobehavioral deficits in Ecuadorian school children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):546–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guodong D, Pei W, Ying T, Jun Z, Yu G, Xiaojin W, et al. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and neurodevelopment in young Shanghai children. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(5):2911–7. doi: 10.1021/es202583d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handal AJ, Lozoff B, Breilh J, Harlow SD. Effect of community of residence on neuro-behavioral development in infants and young children in a flower-growing region of Ecuador. Environ Health Perspect. 2007a;115(1):128–33. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handal AJ, Lozoff B, Breilh J, Harlow SD. Neurobehavioral development in children with potential exposure to pesticides. Epidemiology. 2007b;18(3):312–20. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000259983.55716.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handal AJ, Harlow SD, Breilh J, Lozoff B. Occupational exposure to pesticides during pregnancy and neurobehavioral development of infants and toddlers. Epidemiology. 2008;19(6):851–9. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318187cc5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari R, Julvez J, Murata K, Barr DB, Bellinger DC, Debes F, et al. Neurobehavioral deficits and increased blood pressure in school-age children prenatally exposed to pesticides. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(6):890–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huen K, Bradman A, Harley K, Yousefi P, Barr DB, Eskenazi B, et al. Organophosphate pesticide levels in blood and urine of women and newborns living in an agricultural community. Environ Res. 2012;117:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurewicz J, Hanke W. Prenatal and childhood exposure to pesticides and neurobehavioral development: review of epidemiological studies. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2008;21(2):121–32. doi: 10.2478/v10001-008-0014-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya T, Ceci S. The impact of the flynn effect on LD diagnoses in special education. J Learn Disabil. 2012;45(4):319–26. doi: 10.1177/0022219410392044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofman O, Berger A, Massarwa A, Friedman A, Jaffar AA. Motor inhibition and learning impairments in school-aged children following exposure to organophosphate pesticides in infancy. Pediatr Res. 2006;60(1):88–92. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000219467.47013.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M. Pesticides: a toxic time bomb in our midst. USA: Praeger; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lizardi PS, O’Rourke MK, Morris RJ. The effects of organophosphate pesticide exposure on Hispanic children’s cognitive and behavioral functioning. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33(1):91–101. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Kedan G, Fisker-Andersen J, Kissel J, Fenske R. Multipathway organophosphorus pesticide exposures of preschool children living in agricultural and noagricultural communities. Environ Res. 2004;96(3):283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Barr D, Pearson M, Waller L. Dietary intake and its contribution to longitudinal organophosphorus pesticide exposure in urban/suburban children. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(4):537–42. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks AR, Harley K, Bradman A, Kogut K, Barr DB, Johnson C. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and attention in young Mexican-American children: the CHA-MACOS study. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(12):1768–74. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mula Martos, Figueroa AJ, Ruggeri EN, Giunta MA, Wierna SA, Bonillo NRM, et al. Differences in cognitive execution and cholinesterase activities in adolescents with environmental exposure to pesticides in Jujuy (Argentina) Rev Toxicol. 2005;22(3):180–4. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz MT, Iglesias VP, Lucero BA. Exposure to organophosphate and cognitive performance in Chilean rural school children: an exploratory study. Rev Fac Nac Salud Pública. 2011;29(3):256–63. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Quezada MT, Iglesias V, Lucero B, Steenland K, Barr DB, Levy K, et al. Predictor of exposure to organophosphate pesticides in schoolchildren in the Province of Talca, Chile. Environ Int. 2012;47:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeher L, Tulve N, Egeghy P, Barr D, Adetona O, Fortmann R, et al. Organophosphorus and pyrethroid insecticide urinary metabolite concentrations in young children living in a southeastern United State city. Sci Total Environ. 2010;408:1145–53. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauh VA, Garfinkel R, Perera FP, Andrews H, Barr D, Whitehead D, et al. Impact of prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure on neurodevelopment in the first three years of life among inner-city children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1845–59. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauh VA, Arunajadai S, Horton M, Perera F, Hoepner L, Barr DB, et al. Seven-year neurodevelopmental scores and prenatal exposure to chlorpyrifos, a common agricultural pesticide. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(8):1182–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauh VA, Pereda FP, Horton MK, Whyatt RM, Bansal R, Hao X, et al. Brain anomalies in children exposed prenatally to a common organophosphate pesticide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(20):7871–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203396109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez T, Youglove L, Lu C, Funez A, Weppner S, Barr D, et al. Biological monitoring of pesticide exposures among applicators and their children in Nicaragua. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2006;12(4):312–20. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2006.12.4.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlman DS, Gimenes LS, Eckerman DA, Kang SK, Farahat FM, Kent AW. Development of the behavioral assessment and research system (BARS) to detect and characterize neurotoxicity in humans. Neurotoxicology. 2003;25:523–32. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(03)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlman DS, Arcury TA, Quandt SA, Lasarey M, Rothlein J, Travers R, et al. Neuro-behavioral performance in preschool children from agricultural and non-agricultural communities in Oregon and North Carolina. Neurotoxicology. 2005;26(4):589–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlman DS, Lasarew M, Anger WK, Scherer J, Stupfel J, McCauley L. Neurobehavioral performance of adult and adolescent agricultural workers. Neurotoxicology. 2007;28(2):374–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-García AE, Solís-Heredia MJ, Piña-Guzmán B, Vega L, López-Carrillo L, Quintanilla-Vega B. Genetic polymorphisms and activity of PON1 in a Mexican population. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;205(3):282–9. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas L, Eskenazi B. Pesticides child neurodevelopment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20(2):191–7. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282f60a7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckart P, Kakolewski K, Bove F, Kaye W. Long-term neurobehavioral health effects of methyl parathion exposure in children in Mississippi and Ohio. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(1):46–51. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Miguel Montes LE, Allen DN, Puente AE, Neblina C. Validity of the WISC-IV Spanish for a clinically referred sample of Hispanic children. Psychol Assess. 2010;22(2):465–9. doi: 10.1037/a0018895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudakin DL, Stone DL. Dialkylphosphates as biomarkers of organophosphates: the current divide between epidemiology and clinical toxicology. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011;49(9):771–81. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.624101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadeo J, Sánchez-Brunete C, González L. Pesticides: classification and properties. In: Tadeo J, editor. Analysis of pesticides in food and environmental samples. New York: CRC Press; 2008. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Valcke M, Samuel O, Bouchard M, Dumas P, Belleville D, Tremblay C. Biological monitoring of exposure to organophosphate pesticides in children living in peri-urban areas of the Province of Quebec, Canada. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2006;79:568–77. doi: 10.1007/s00420-006-0085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vida P, Moretto A. Pesticide exposure pathways among children of agricultural workers. J Public Health. 2007;15:289–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wessels D, Barr DB, Mendola P. Use of biomarkers to indicate exposure of children to organophosphate pesticides: implications for a longitudinal study of children’s environmental health. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(16):1939–46. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P, Weiss L, Rolfhus E. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV, technical report 1, theoretical model and test blueprint. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Williams P, Weiss L, Rolfhus E. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV, technical report 2, psychometric properties. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Whyatt RM, Barr DB, Camann DE, Kinney PL, Barr JR, Andrews HF, et al. Contemporary-use pesticides in personal air samples during pregnancy and blood samples at delivery among urban minority mothers and newborns. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(5):749–56. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JG, Eskenazi B, Gladstone EA, Bradman A, Pedersen L, Johnson C, et al. Association between in utero organophosphate pesticide exposure and abnormal reflexes in neonates. Neurotoxicology. 2005;26(2):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitz P, Kakolewski K, Imtiaz R, Kaye W. Methods of assessing neurobehavioral development in children exposed to methyl parathion in Mississippi and Ohio. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(6):1079–83. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s61079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]