Abstract

Social work students (n = 60) in a master’s-level course on severe mental illness participated in a quasi-experimental study examining the degree to which increased knowledge about and contact with individuals with schizophrenia during the course would impact their attitudes toward people with the disorder. Results revealed significant improvement in student knowledge and general attitudes after the course, and indicated that increased knowledge about schizophrenia was only related to general attitudinal improvement when accompanied by increased personal social contact. Implications for education on severe mental illnesses, and value and attitude development in social work education are discussed

Social work education must instill the knowledge and skills that aspiring social workers need to succeed in their efforts to improve the lives of the often underserved and disenfranchised groups with which we work (Council on Social Work Education, 2008). Equally important is to ensure that students also gain the values, in addition to knowledge and skills, they need in order to become effective social workers (Haynes, 1999). The espousal of appropriate social work values and attitudes is particularly important when working with some of the most socially stigmatized groups, such as racial minorities, individuals with same sex orientations, and those with psychiatric disabilities. Within the field of mental health, schizophrenia is perhaps the most highly stigmatized of all psychiatric disabilities. Schizophrenia is considered a severe mental illness (SMI), which includes mental disorders that are characterized by high degrees of disability and persistence over time (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001). Among the various SMIs, schizophrenia is one of the most disabling in terms of the significant impact of the illness on every sphere of an individual’s life (Thaker & Carpenter, 2001). Social workers are the primary providers of psychosocial interventions for individuals with schizophrenia in the United States (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001). Unfortunately, despite the recognition of the central role of social work in providing services to clients with schizophrenia, few studies have addressed the education and training needs for working with this population, particularly with regard to attitude and value development (Newhill & Korr, 2004). Notable education campaigns have begun (e.g., the California Social Work Education Center), but there is still a need for more focused research on the best methods for preparing social workers for effectively serving people with schizophrenia.

Although most social workers are well aware of what might be called the structural barriers to working with clients with schizophrenia, such as lack of resources, the fragmented nature of the mental health system, lack of or inadequate insurance coverage, and so forth, it is the impact of stigma, lack of accurate knowledge, and negative attitudes toward individuals with the condition that can constitute some of the most intractable barriers toward effectively serving this population. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated that there is a near-ubiquitous stigmatizing and negative view toward people with schizophrenia around the world (Lee, 2002). Among the most persistent is that such individuals are dangerous (Angermeyer & Matschinger, 2005; Penn, Kohlmaier, & Corrigan, 2000), despite repeated evidence that those living with serious mental illness are much more likely to be the victims, rather than perpetrators of violence (Teplin, McClelland, Abram, & Weiner, 2005).

Unfortunately, social workers and mental health professionals are not immune to internalizing the stereotypes, biases, and continuing social stigma that surrounds society’s attitudes toward people with schizophrenia (e.g., Murray & Steffen, 1999; Schwartz, 2004). Perhaps most importantly, studies have shown that the attitudes professionals hold toward individuals with schizophrenia make an important contribution to recovery and outcome among this population (e.g., Barrowclough et al., 2001; Moore & Kuipers, 1992; Snyder et al., 1996). This would hardly seem surprising given that individuals who espouse stigmatizing beliefs and negative attitudes about schizophrenia often find it difficult to remain positive during treatment and provide the best quality of care (Oliver & Kuipers, 1996). That attitudes and values can have such an impact on practice clearly highlights the importance of addressing stigma and promoting self-evaluation in social work education, so that students are prepared to effectively serve marginalized and stigmatized populations, such as people who live with schizophrenia. What is less clear, however, is exactly how to facilitate the process of attitude and value development in the classroom.

Given that negative attitudes develop, in part, from a lack of accurate knowledge about a stigmatized group (Allport, 1954; Sherman, 1996; Weber & Crocker, 1983), the provision of accurate information about schizophrenia to social work students represents one important avenue for facilitating positive attitudes toward this population. In addition, research has shown that having personal contact with an individual from a stigmatized group can improve attitudes and reduce prejudice and discrimination by blurring inter-group boundaries, reducing inter-group anxiety, and increasing direct personal knowledge about the population (Author, 2008b; Hewstone, 2003; Pettigrew, 1998). This has led to recommendations regarding information campaigns and increased positive contact with people with schizophrenia as methods of reducing societal stigma in general (Corrigan, Watson, Warpinski, & Gracia, 2004). Such recommendations have important implications for how we might educate students preparing for careers in psychiatric social work. Unfortunately, little is known about whether such efforts are effective in social work education.

We recently reported the results of a cross-sectional study showing that both knowledge and interpersonal contact were significant contributors to positive attitudes toward people with schizophrenia among a group of MSW students (Author, 2008b). However, we also observed that knowledge only contributed to positive attitudes among students who had higher levels of interpersonal contact with those with the disorder. While these findings suggested an important interplay between knowledge and contact with individuals with schizophrenia in shaping students attitudes, their cross-sectional nature made it difficult to discern whether imparting students with greater knowledge and/or contact with this population would truly be able to shift student attitudes over time.

In the current investigation, we conducted a quasi-experimental study of changes in MSW student attitudes about schizophrenia before and after completing a course on social work practice with individuals with SMI. This course was designed, in part, to provide the latest knowledge about schizophrenia and its treatment, as well as initial exposure to people and families who live with the illness. The specific research question addressed by this study was whether increased knowledge and contact with persons with schizophrenia that occurred during this course would be associated with improved attitudes toward this population over time, in an effort to elucidate the mechanisms by which value and attitude development surrounding this highly stigmatized population can be supported in social work education. In addition, the interactive effects of personal contact with individuals with schizophrenia and previous undergraduate social work training on attitudinal change were explored.

Method

Participants

Participants consisted of a convenience sample of 60 MSW students in a social work practice course on working with adults with SMI. The average age of participants was 30.57 (SD = 10.04) years, and the majority were female (n = 50) and Caucasian (n = 53). The educational background of participants was diverse, although the most (n = 42) had received a previous degree in a human service field with 10 individuals having completed undergraduate social work training. All participants were in the direct practice MSW concentration, with 56 specializing in mental health, 2 specializing in child welfare, 1 participant specializing in health care, and 1 participant not reporting his/her specialization. The majority of participants (n = 45) were full-time students in the MSW program.

Social Work Practice with Severe Mental Illness Course

The course for which this study was conducted is an original course developed by the second author, and designed as an introduction to the knowledge, values and skills employed in clinical social work practice with clients with severe and persistent mental illness and their families. The course addresses working with clients with schizophrenia, other severe mental illnesses including severe personality disorders, as well as challenging groups such as involuntary clients, violent and aggressive clients, and clients with both mental illness and substance use problems. The overall purpose is to equip second-year MSW students with the knowledge, skills, and values requisite for working effectively with the types of clients most commonly seen in public behavioral health services. From 1991–1994, the course was taught as an MSW direct practice elective class, however, because it was so well received by the students, it was selected by the faculty to be the required skills course for all MSW students in the mental health specialization track in 1994 and has been offered every semester since that time. To bring the class “alive”, clinical material from the instructor’s own practice experience is utilized and students are encouraged to bring in case material from their internships for illustration, clinical analysis and discussion. In addition, multiple efforts are made to increase meaningful contact with persons with schizophrenia and help students understand the experience of living with or caring for someone with a serious mental illness. These efforts include assigning personal accounts written by consumers and family members in the required course reader, inviting consumers with schizophrenia and family members to speak to the class about their experiences and perspective, and the assignment of a structured creative research paper in which students write about how their own life course might have changed if they were diagnosed with a serious mental illness. Approximately 20% of the course is dedicated to providing information specifically on schizophrenia, and many other aspects of the course cover content relevant to people with schizophrenia (e.g., working with clients who are receiving services involuntarily), which resulted in students having consistent exposure to this topic throughout the course.

Measures

Knowledge about schizophrenia

Students’ knowledge about schizophrenia was assessed using the Knowledge About Schizophrenia Questionnaire (KASQ; Ascher-Svanum, 1999). The KASQ is a 25-item multiple choice questionnaire covering knowledge about the treatment (e.g., “Common side-effects of antipsychotic drugs are …”), symptoms (e.g., “A person with schizophrenia nearly always has [the following symptoms]”), and etiology of schizophrenia (e.g., “Which of the following is a possible cause of schizophrenia?”). An abbreviated, 19-item version of the instrument was used in this study, based on findings from our previous study that excluded items that had shown low variability and reliability among an MSW student population (Eack & Newhill, 2008b). The KASQ has shown adequate internal consistency and high test-retest reliability in studies with individuals with schizophrenia (Ascher-Svanum, 1999), and we have shown it to be reliable and associated with attitudinal measures in previous research with social work students (Author, 2008b).

Attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia

The attitudes social work students held toward individuals with schizophrenia were assessed using a 13-item self-report questionnaire used in previous research (Author, 2008b). This measure was designed to assess social work students’ general attitudes about individuals with schizophrenia (8 items), (e.g., “Individuals with schizophrenia are dangerous”, “Individuals with schizophrenia can lead full and satisfying lives”, “I would not want to live next door to an individual who has schizophrenia”), as well as their attitudes about working with individuals with this illness (5 items) (e.g., “I would find little satisfaction in working with individuals with schizophrenia”). General attitudes were defined as global attitudinal statements about people with schizophrenia reflecting stereotyped views toward this population. Attitudes toward working with people with schizophrenia were defined as views about preference, satisfaction, and perceived efficacy for engaging in social work practice with people with this condition. Items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 6 (“strongly agree”), and negative items were reverse coded such that higher scores represented more positive attitudes. This instrument was developed based on the Opinions About Mental Illness scale (Cohen & Struening, 1962) and Community Attitudes Toward Mentally Ill scale (Taylor & Dear, 1981), as well as previous work assessing social workers’ attitudes toward individuals with SMI (Author, 2008a; Newhill & Korr, 2004). We have previously observed this scale to possess adequate levels of internal consistency and to contain a factor structure reflective of its general and work desirability attitudinal dimensions (Author, 2008b).

Contact with individuals with schizophrenia

The degree and frequency of contact participants had with individuals with schizophrenia was captured using a 9-item social distance measure asking participants to indicate the various levels of exposure they have had to this population; and a 5-point graphic scale asking participants to rate, from “never” to “daily”, the frequency with which they have contact with persons with schizophrenia. Degree of contact items ranged from exposure to observational/medial depictions of schizophrenia (e.g., “I have watched a television program/movie or read a newspaper/magazine article about a person with schizophrenia”), to previous work experience with people with schizophrenia, to living in the same household as an individual with the condition. Items were weighted based on their social distance, with lower scores indicating greater social distance, and total degree of contact was computed by summing across the 9 weighted social distance items.

Procedures

Participants were recruited by their social work instructors from two sections of the social practice with persons with SMI course outlined above. Upon recruitment, participants were asked to complete a survey of their knowledge about, contact with, and attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia. The measures of knowledge, contact, and attitudes described above were administered during regularly scheduled classroom time during the first and last sessions of the course. Instructors informed students that their participation was completely voluntary and would not affect their grade or standing in the class or in any way, and that if they did not want to participate, they could simply turn in a blank survey packet. During the survey, the instructor was required to leave the room, while students returned the surveys, completed or not, to an envelope located at the front of the classroom. The envelope was then sealed and retrieved by one of the authors not involved in teaching either of the course sections. This research was approved by the university Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Analysis proceeded by first conducting a series of linear mixed-effects change models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), adjusting for potentially confounding age and gender effects, to examine the size and significance of pre-post course changes in student knowledge, contact, and attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia. These models allowed individual starting points and rates of change in knowledge, contact, and attitudes to vary randomly across students. Moderator analyses were also conducted using linear mixed-effects change models to examine the degree to which undergraduate training in social work affected rates of attitudinal improvement. Subsequently, associations between changes in student attitudes, and increased knowledge about and contact with persons with schizophrenia were examined by entering knowledge and contact time-varying covariates into linear mixed-effects changes models. Finally, moderator analyses within these change models were conducted to examine the effect of interactions between increased knowledge and contact on the rates of improvement in students’ attitudes.

Results

Changes in MSW Student Knowledge and Attitudes About Schizophrenia

We began our examination of the effects of the SMI curriculum on attitudes by first investigating the degree to which changes in student attitudes, knowledge, and contact regarding schizophrenia occurred. As shown in Table 1, highly significant improvements in student knowledge were observed upon completion of this course. These improvements were of medium size, and approached a 90% accuracy rate. Most importantly, not only did student knowledge about schizophrenia increase, but their general attitudes toward this population also demonstrated a significant and medium-sized level of improvement. However, no significant changes were observed with regard to attitudes toward working with individuals with schizophrenia, nor were any overall changes observed in the average amount of contact students had with this population. Such findings suggest that teaching MSW students about schizophrenia may not only improve their knowledge, but also their general attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia.

Table 1.

Effects of Severe Mental Illness Education on Student Knowledge of, Attitudes Toward, and Contact with Individuals with Schizophrenia.

| Variable | Pre-Course | Post-Course | Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | F | p | d | |

| Knowledge (% Correct) | 85.73 (6.56) | 89.01 (6.29) | 17.56 | < .001 | .50 |

| Attitudes | |||||

| General | 4.49 (.52) | 4.72 (.53) | 5.99 | .018 | .44 |

| Toward Working | 4.75 (.79) | 4.58 (.74) | 2.45 | .124 | -.22 |

| Contact | |||||

| Degree | 5.98 (2.90) | 6.19 (2.86) | .07 | .798 | .07 |

| Frequency | 1.91 (1.23) | 2.04 (1.20) | .39 | .537 | .10 |

Note. Means are adjusted from linear mixed-effects models accounting for age and gender effects.

Next we conducted a series of exploratory analyses to examine the degree to which initial social work preparation prior to entering the MSW program would enhance attitudinal improvement toward individuals with schizophrenia when learning about the disorder. While students without a BSW degree did show some improvement in their general attitudes toward people with schizophrenia, those with a BSW degree demonstrated significantly greater attitudinal improvement, F(1, 47) = 7.19, p = .010. In addition, while no overall effect on attitudes toward working with individuals with schizophrenia was observed during the course, a significant disordinal interaction was observed between those with a BSW degree and those without undergraduate social work training, F(1, 47) = 7.58, p = .008. Interestingly, while those with a BSW degree showed improved attitudes toward working with people with schizophrenia after the course, those without a BSW, on average, expressed a decreased desire to work with such individuals.

Associations Between Changes in Knowledge and Contact with Attitudinal Change About Schizophrenia

Having found that students’ knowledge and general attitudes toward working with individuals with schizophrenia improved during the course on SMI, we proceeded to examine the degree to which increased knowledge and contact with this population contributed longitudinally changes in student attitudes. As shown in Table 2, changes in student general attitudes toward people with schizophrenia were relatively independent of changes in knowledge or contact, as none of these measures demonstrated a significant relationship with general attitudinal improvement over time. Conversely, increases in knowledge were significantly associated with improved attitudes toward working with individuals with schizophrenia. In addition, increased frequency of contact with those with schizophrenia also promoted better attitudes toward working with this population.

Table 2.

Associations Between Improved Attitudes Toward Individuals with Schizophrenia and Changes in Knowledge and Contact During Severe Mental Illness Education.

| Predictor | General Attitudes

|

Attitudes Toward Working

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | B | SE | p | |

| ΔKnowledge (% Correct) | .002 | .09 | .963 | .32 | .09 | .001 |

| ΔContact | ||||||

| ΔDegree | −.03 | .11 | .804 | .07 | .10 | .511 |

| ΔFrequency | .15 | .11 | .171 | .22 | .10 | .033 |

| Time | .30 | .13 | .028 | −.34 | .13 | .010 |

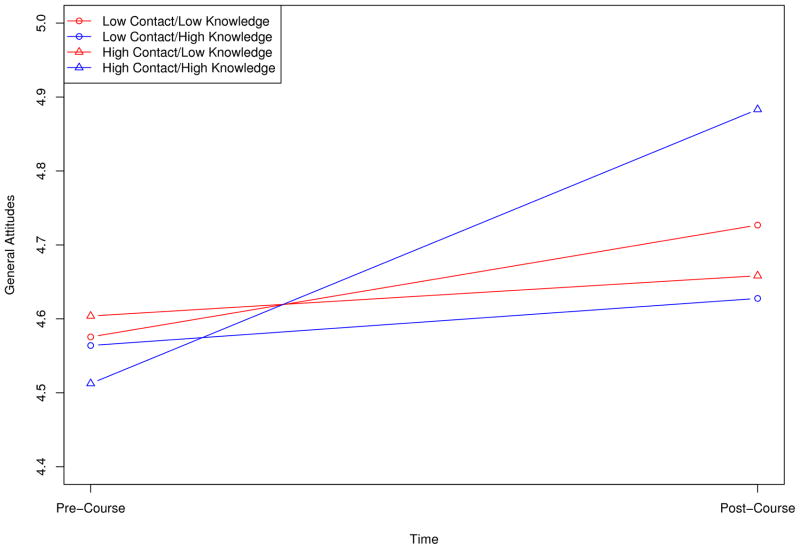

When examining the longitudinal interactive effect of changes in knowledge and contact on attitudinal changes toward people with schizophrenia, a significant interaction was observed between increased social contact and knowledge on improvement in students’ general attitudes, F(1, 44) = 7.20, p = .010. As can be seen in Figure 1, general attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia showed little improvement for students who had a low degree of contact with this population, regardless of how much their knowledge improved. However, students who increased their knowledge about schizophrenia and had closer contact with people with the disorder showed sharp improvements in their general attitudes toward such individuals. This effect was only observed for the degree or closeness of contact students had with this population, and not frequency of contact. No interaction effects between knowledge and contact were found with regard to attitudes toward working with people with schizophrenia. Together, these findings point to the limited impact of knowledge improvements on student attitudes toward people with schizophrenia, and the need to reduce social distance from this population in conjunction with providing education about the condition.

Figure 1.

Moderating Effect of Increased Personal Contact on the Impact of Improved Knowledge on Changes in MSW Student Attitudes Toward Individuals with Schizophrenia.

Discussion

Social workers frequently practice with marginalized and highly stigmatized groups, and they are not immune to the prejudices that society affords to individuals who belong to these groups. This characteristic of our profession makes it exceedingly important to attend to the development of appropriate attitudes and values during social work education. Within the field of mental health, schizophrenia represents one of the most disabling and stigmatized of all psychiatric disabilities, and social workers are the primary providers of psychosocial services for individuals who live with this disorder (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001). It is critical that the many social work students who will directly serve this population not only have the requisite knowledge and skills needed to help those with schizophrenia, but also the attitudes and values needed to succeed in their work and combat stigma against people living with the condition. Unfortunately, facilitating attitudinal development and change within social work education remains a largely enigmatic task.

In this study, we sought to examine the longitudinal contribution of changes in knowledge and contact with persons with schizophrenia to improved attitudes toward this population in MSW students participating in a course on SMI. Results revealed that overall students’ knowledge and general attitudes showed some improvement throughout the course, and that increased knowledge and contact with people with schizophrenia were associated with longitudinal improvement in attitudes toward working with this population. However, when examining general attitudinal change, no significant direct effect of increased knowledge and contact was observed. Rather, increased knowledge about schizophrenia was only associated with improved general attitudes toward this population for students who had closer contact with individuals with this disorder. These longitudinal findings replicate our previous cross-sectional results (Author, 2008b), and continue to suggest the importance of providing both knowledge and personal contact with stigmatized groups to facilitate attitude and value development in social work education.

These findings need to be recognized within the context of a number of limitations. First, this research was characterized by a relatively modest sample size, which may have precluded the detection of smaller relations between student attitudes, knowledge, and contact with individuals with schizophrenia. In addition, the sample was relatively homogeneous, consisting primarily of Caucasian females, which may limit the generalizability of these findings. Further, the absence of a group of matched control students precludes firm conclusions regarding the causal effect of course experiences on knowledge and attitude outcomes. However, the primary focus of this research was centered around examining how longitudinal changes in knowledge and contact were related to attitudinal change, rather than attempting to establish the specific efficacy of the course in which these changes occurred. In addition, students were selected from a single university in the East, and the results of this study may not generalize beyond this sample of students. While these findings continue to build support for the effect of knowledge and contact on attitude development toward individuals with schizophrenia, they need to be interpreted with caution until future studies employing larger sample sizes are conducted. Finally, it is important to note that students’ pre-course knowledge about and attitudes toward those with schizophrenia was relatively high. Although sufficient variability was available to detect relationships between knowledge, contact, and attitudinal change, the magnitude of these relations may have been attenuated due to restricted range. This characteristic of the sample is likely reflective of the advanced training students already had received in social work practice and mental health. Future studies might profitably expand their sample to first-year social work students who have not already received advanced mental health training.

Despite these limitations, this research has a number of potential implications for social work education and practice. First, even in this sample where the majority of students had already received advanced training in mental health, the severe mental illness course developed was able to continue to improve students’ knowledge about and attitudes toward schizophrenia. This course, listed as “Clinical Skills and Psychopathology” at the University of Pittsburgh, has been continuously offered since 1991, and its materials and approach have been refined over the years. As we have noted (Author, 2008b; Newhill & Korr, 2004), there is an unsettling dearth of adequate training on severe mental illness generally in social work education, despite the fact that social work is responsible for a large majority of the care of individuals who live with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses. Notable initiatives have begun in California and other select states, however there is a need for more widespread and systematic enhancement of this area of social work education. Thus, while controlled studies are required to more definitively establish the efficacy of this course for improving student knowledge and attitudes about schizophrenia, we view a significant contribution of this work as the initial testing of a comprehensive course on severe mental illness designed to provide students with the knowledge and attitudes they need to practice effective social work with this population.

Second, this research has important implications for the type of contact that would appear to be important to provide students in social work education, when attempting to facilitate attitude and value development. Our findings show that when considering general attitude development, frequency of contact with a stigmatized group has little impact on students’ attitudes. Conversely, those students who had closer contact with individuals with schizophrenia tended to demonstrate improved general attitudes, as long as they were able to also increase their knowledge about the disorder. This pattern of results is not particularly surprising, given that frequent superficial contact is not likely to contain the personal interactions needed to shift attitudes, and supports previous work by Shor and Sykes (2002) indicating that close structured dialogues with people with severe mental illness can help improve the attitudes of social work students. Further, frequent contact at high levels of social distance, such as only observing medial depictions, could even have a negative impact on students’ attitudes, given that socially distant depictions of stigmatized groups are frequently negative (Wahl, 2006). It is also understandable that a sufficient level of knowledge has to be gained before close interpersonal contact can be used to facilitate positive general attitude development, as interacting closely with someone with schizophrenia without knowing what to expect or how to behave appropriately could result in a negative interaction. Taken together, these findings suggest that social work educators may be able to facilitate positive general attitude development toward individuals with schizophrenia by first providing requisite knowledge about the illness, and then ensuring that students engage in close, positive interactive experiences with this population. Field education is an ideal pedagogical method for supporting this type of informed, meaningful contact with stigmatized groups, and these findings are aligned with the Council on Social Work Education’s selection of field education as the signature pedagogy in social work (Council on Social Work Education, 2008).

Third, the facilitation of improved attitudes toward people with schizophrenia in social work education is likely to have significant implications for social work practice and the recovery of people with this disability. Numerous studies have shown that when caregivers of people with schizophrenia possess negative attitudes toward this population, individuals with this disability are likely to have worse outcomes (Barrowclough et al., 2001; Moore & Kuipers, 1992; Snyder et al., 1996). Practitioners who hold stereotypic beliefs that their clients cannot get better, are violent, and intractable are less likely to employ beneficial interventions. Further, even when interventions are applied, if a social worker adopts a negative attitudinal approach, such interventions are less likely to be provided in an effective manner. As such, the implications of fostering positive attitudes toward people with schizophrenia in social work education are likely to be great as students begin practicing in the field.

Finally, it is interesting to note that attitudinal improvement was greater for students who held an undergraduate degree in social work. Undergraduate social work training has been shown to contribute to some improved educational outcomes (Knight, 1993), although other studies have not supported this (Fortune, Green, & Kolevzon, 1987). Although exploratory and limited by a modest sample size, the results of this research may reflect the importance of foundational social work training in achieving greater attitudinal gains in master’s-level social work curricula. Undergraduate education in social work may help students adopt early on, the values of the social work profession and the need for continued self-examination and attitude development. Those trained initially in other disciplines may have difficulty making this shift to critical self-appraisal regarding values and attitudes, which could hamper efforts to improve attitudes in social work education. Findings regarding a decrease in desirability toward working with individuals with schizophrenia among students not originally trained in social work were unexpected. Tentatively, we speculate that this may reflect a greater commitment of undergraduate social workers toward this population, although future studies are needed to clarify this finding.

In summary, this study found that by providing MSW students with education on severe mental illness, positive changes in attitudes toward schizophrenia could be achieved. As we observed previously (Author, 2008b), attitude change was at least partially dependent upon both knowledge about and contact with this population, and that general attitudinal improvement could not be realized with increased knowledge or contact alone. These findings support efforts to increase content knowledge about severe mental illness within the context of close, positive interpersonal interactions in social work education, as a method of preparing students to have the knowledge, values, and attitudes needed to successfully serve the many individuals who live with schizophrenia.

References

- Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Cambridge MA: Addison-Wesley; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Labeling-stereotype-discrimination: An investigation of the stigma process. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2005;40:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0903-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascher-Svanum H. Development and validation of a measure of patients’ knowledge about schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:561–563. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrowclough C, Haddock G, Lowens I, Connor A, Pidliswyj J, Tracey N. Staff expressed emotion and causal attributions for client problems on a low security unit: An exploratory study. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001;27:517–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Struening EL. Opinions about mental illness in the personnel of two large mental hospitals. Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology. 1962;64:349–360. doi: 10.1037/h0045526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Warpinski AC, Gracia G. Implications of educating the public on mental illness, violence, and stigma. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:577–580. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council on Social Work Education. Educational policy and accreditation standards. Alexandria, VA: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Newhill CE. An investigation of the relations between student knowledge, personal contact, and attitudes toward individuals with schizophrenia. Journal of Social Work Education. 2008b;44:77–95. doi: 10.5175/JSWE.2008.200700009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune AE, Green RG, Kolevzon MS. In search of the continuum: Graduate school performance of BSW and non-BSW degree holders. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. 1987;14:169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes DT. A theoretical integrative framework for teaching professional social work values. Journal of Social Work Education. 1999;35:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hewstone M. Intergroup contact: Panacea for prejudice? Psychologist. 2003;16:352–355. [Google Scholar]

- Knight C. A comparison of advanced standing and regular master’s students’ performance in the second-year field practicum: Field instructors’ assessments. Journal of Social Work Education. 1993;29:309–309. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. The stigma of schizophrenia: A transcultural problem. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2002;15:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Moore E, Kuipers L. Behavioural correlates of expressed emotion in staff^patient interactions. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1992;27:298–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00788902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MG, Steffen JJ. Attitudes of case managers toward people with serious mental illness. Community mental health journal. 1999;35:505–514. doi: 10.1023/a:1018707217219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhill CE, Korr WS. Practice with people with severe mental illness: Rewards, challenges, burdens. Health & Social Work. 2004;29:297–305. doi: 10.1093/hsw/29.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver N, Kuipers E. Stress and its relationship to expressed emotion in community mental health workers. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1996;42:150–159. doi: 10.1177/002076409604200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn DL, Kohlmaier JR, Corrigan PW. Interpersonal factors contributing to the stigma of schizophrenia: Social skills, perceived attractiveness, and symptoms. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;45:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF. Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:65–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush DSW, Bryk DAS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz C. The attitudes of social work students and practicing psychiatric social workers toward the inclusion in the community of people with mental illness. Social Work in Mental Health. 2004;2:33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman JW. Development and mental representation of stereotypes. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1996;70:1126–1141. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shor R, Sykes IJ. Introducing Structured Dialogue with people with mental illness into the training of social work students. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2002;26:63–69. doi: 10.2975/26.2002.63.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder KS, Wallace CJ, Moe K, Ventura J, et al. The relationship of residential care-home operators’ expressed emotion and schizophrenic residents’ symptoms and quality of life. International Journal of Mental Health. 1996;24:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Mental health, United States: 2000. Washington, DC: Author; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SM, Dear MJ. Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1981;7:225–240. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Weiner DA. Crime victimization in adults with severe mental illness: comparison with the National Crime Victimization Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:911–921. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaker GK, Carpenter WT. Advances in schizophrenia. Nature Medicine. 2001;7:667–671. doi: 10.1038/89040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl OF. Mass media images of mental illness: A review of the literature. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;20:343–352. [Google Scholar]

- Weber R, Crocker J. Cognitive processes in the revision of stereotypic beliefs. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1983;45:961–977. [Google Scholar]