Abstract

Galactomannan biosynthesis in legume seed endosperms involves two Golgi membrane-bound glycosyltransferases, mannan synthase and galactomannan galactosyltransferase (GMGT). GMGT specificity is an important factor regulating the distribution and amount of (1→6)-α-galactose (Gal) substitution of the (1→4)-β-linked mannan backbone. The model legume Lotus japonicus is shown now to have endospermic seeds with endosperm cell walls that contain a high-Gal galactomannan (mannose [Man]/Gal = 1.2-1.3). Galactomannan biosynthesis in developing L. japonicus endosperms has been mapped, and a cDNA encoding a functional GMGT has been obtained from L. japonicus endosperms during galactomannan deposition. L. japonicus has been transformed with sense, antisense, and sense/antisense (“hairpin loop”) constructs of the GMGT cDNA. Some of the sense, antisense, and sense/antisense transgenic lines exhibited galactomannans with altered (higher) Man/Gal values in their (T1 generation) seeds, at frequencies that were consistent with posttranscriptional silencing of GMGT. For T1 generation individuals, transgene inheritance was correlated with galactomannan composition and amount in the endosperm. All the azygous individuals had unchanged galactomannans, whereas those that had inherited a GMGT transgene exhibited a range of Man/Gal values, up to about 6 in some lines. For Man/Gal values up to 4, the results were consistent with lowered Gal substitution of a constant amount of mannan backbone. Further lowering of Gal substitution was accompanied by a slight decrease in the amount of mannan backbone. Microsomal membranes prepared from the developing T2 generation endosperms of transgenic lines showed reduced GMGT activity relative to mannan synthase. The results demonstrate structural modification of a plant cell wall polysaccharide by designed regulation of a Golgi-bound glycosyltransferase.

Those leguminous seeds that retain an endosperm in the mature state (the endospermic legumes) always have endosperm cell walls that consist almost entirely of galactomannans. The galactomannans are multifunctional molecules. Before and during germination, their hydrophilic properties enable the endosperm to imbibe water and to deploy it to buffer the embryo against subsequent drought (Reid and Bewley, 1979). After germination, they are mobilized as storage reserves (Reid, 1985). The molecules themselves are composed of a (1→4)-β-linked mannan backbone that carries single-unit galactosyl side chains attached (1→6)-α. Their hydrophilic properties result from their highly branched structure (Man/Gal between 1.1 and about 3.5; Meier and Reid, 1982; Reid, 1985). Some legume seed galactomannans are used in industry. Once isolated from the seeds, they are water soluble and of high Mr, giving viscous solutions that, on drying, form coherent, air-tight films that rehydrate only slowly. Their applications exploit these properties (Dea and Morrison, 1975; Reid and Edwards, 1995). In the food context, it is well established that Gal content critically affects the commercial functionality of legume seed galactomannans. Valuable rheologies based on mixed polysaccharide interactions and low temperature gelation (used e.g. to stabilize ice cream) are exhibited only by those galactomannans with Gal contents toward the lower end of the natural range (Dea et al., 1977; Richardson and Norton, 1998).

The mechanism and regulation of galactomannan biosynthesis has been studied comparatively in the developing seed endosperms of three legume species: fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum; Man/Gal = 1.1) guar (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L. Taub.; Man/Gal = 1.6), and senna (Senna occidentalis L. Link.; Man/Gal = 3.3; Campbell and Reid, 1982; Edwards et al., 1989, 1992; Reid et al., 1995). Two tightly membrane-bound glycosyltransferases together catalyze the polymerization of galactomannans: a GDP-Man (and Mg+2)-dependent (1→4)-β-d-mannosyltransferase or “mannan synthase” (MS) and a UDP-Gal (and Mn+2)-dependent mannan-specific (1→6)-α-d-galactosyltransferase (“galactomannan galactosyltransferase” [GMGT]). In microsomal membrane preparations, the interaction of MS and GMGT in galactomannan biosynthesis in vitro conforms to an experimental model whereby Gal is transferred only to an acceptor Man residue at or near the elongating nonreducing end of the mannan backbone (Edwards et al., 1989). Transfer of Gal residues conforms to statistical rules whereby the probability of obtaining Gal substitution at the acceptor Man residue is determined by the existing states of substitution at the nearest neighbor and second nearest neighbor Man residues (toward the reducing terminus) of the elongating backbone. This is a second order Markov chain model. Furthermore, the maximum degrees of Gal substitution allowed by the deduced Markov probabilities for fenugreek, guar, and senna membranes are very close to those observed for the primary product (Edwards et al., 1992) of galactomannan biosynthesis in vivo (Reid et al., 1995). Thus, the biosynthesis of galactomannans requires a specific functional interaction between MS and GMGT, within which the transfer specificity of the GMGT is important in determining the statistical distribution of galactosyl residues along the mannan backbone and the Man/Gal ratio (Edwards et al., 2002).

The GMGT of fenugreek has been detergent solubilized with retention of activity, enabling its full molecular characterization with proof of functional identity (Edwards et al., 1999). The enzyme is a type II membrane protein with a single transmembrane α-helix close to the N terminus that ensures its anchorage to the Golgi membrane. Neither the α-helix nor the short N-terminal domain are required for catalytic action (Edwards et al., 1999). The detergent-solubilized fenugreek GMGT has a principal acceptor substrate recognition sequence of six (1→4)-β-linked Man residues, with transfer occurring at the third Man residue from the nonreducing end of the sequence (Edwards et al., 2002).

We now show that the seeds of the model legume plant Lotus japonicus are endospermic, containing a galactomannan that is highly Gal substituted (Man/Gal = 1.2-1.3), and we map the time course of galactomannan biosynthesis. We also report the isolation from developing L. japonicus endosperms of a cDNA encoding a functional GMGT, and we explore variations in galactomannan structure and amount in the endosperms of seeds from L. japonicus transgenic lines transformed with L. japonicus GMGT cDNA constructs designed to induce posttranscriptional silencing.

RESULTS

The Seeds of L. japonicus Ecotype Gifu Are Endospermic and Contain a High-Gal Galactomannan

L. japonicus (Regel) Larsen ecotype Gifu is one of a limited number of readily transformable “model legume” plants (Handberg and Stougaard, 1992). It is diploid, self-fertile, has a relatively short generation time, and produces relatively large quantities of seeds. Another species from the genus Lotus has long been known to be endospermic (Nadelmann, 1890). On light microscopic examination, the seeds of L. japonicus clearly contained a well-developed endosperm that could be dissected free of testa and embryo. Gal and Man accounted for over 93% of the neutral sugars released on acid hydrolysis of total cell wall material prepared from endosperms isolated by dissection, and the Man/Gal value was 1.23 (Table I). Thus, the galactomannan in the cell walls of the L. japonicus seed endosperm has a degree of Gal substitution near the higher end of the natural range.

Table I.

Neutral sugar composition of total cell wall material from L. japonicus endosperm

| Monosaccharide | Araa | Gal | Glc | Xyl | Man | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mol % | 4.5 | 42 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 51.5 | 100 |

May include a trace of Rha

Galactomannan Biosynthesis in Developing L. japonicus Seeds

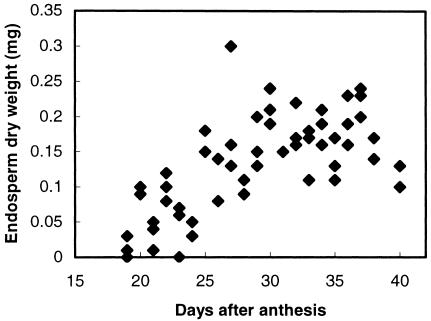

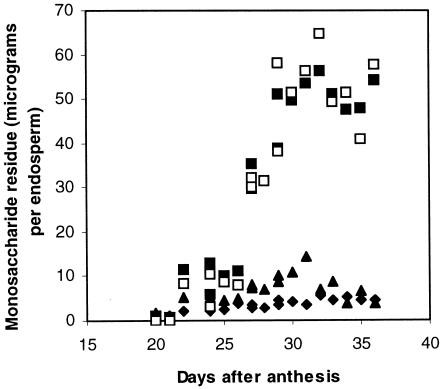

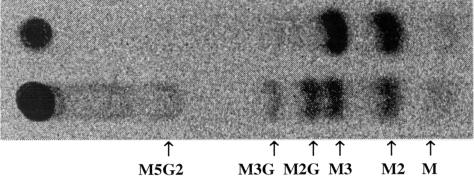

Cell wall deposition in the developing L. japonicus endosperm was mapped by tagging flowers at anthesis and scoring developing seed endosperms for dry weight and for the amount and composition of their total cell wall materials. Dry matter began to be deposited in the endosperm around 20 d after anthesis and ended by about d 35 (Fig. 1). Residues of Man and Gal accumulated steadily in the endosperm cell walls throughout the period of dry weight accumulation, whereas levels of the other monosaccharides remained low and fairly constant (Fig. 2). Microsomal membrane preparations from endosperms isolated approximately 28 d after anthesis catalyzed the incorporation of label from GDP-(14C) Man alone and from GDP-(14C) Man plus unlabeled UDP-Gal into labeled 70% (v/v) methanol-insoluble products. These products were characterized using the pure, structure-sensitive endo-(1→4)-β-d-mannanase the action of which has been described in detail by McCleary and Matheson (1983). The optimum substrate subsite-binding requirement of this enzyme is a stretch of five (1→4)-β-linked d-mannosyl residues, although mannotetraose is nonetheless hydrolyzed slowly. Thus, the products of digestion of an unsubstituted (1→4)-β-mannan are mannobiose (M2) and mannotriose (M3), usually accompanied by some Man. Gal substitution at the Man residues occupying the second and/or the fourth position within the binding sequence prevents hydrolysis, with the result that only certain well-defined fragment oligosaccharides are released from galactomannans by the action of the enzyme (McCleary, 1979; McCleary and Matheson, 1983). The smallest of these allowed oligosaccharides are M2, M3, and the three Gal-substituted manno-oligosaccharides monogalactosylmannobiose, monogalactosylmannotriose, and digalactosylmannopentaose, the molecular structures of which are illustrated in Edwards et al., 2002. Figure 3 documents the labeled manno- and galactomanno-oligosaccharides released from the labeled in vitro products on digestion with the Aspergillus niger endo-β-mannanase. The labeled product formed with GDP-(14C) Man alone released labeled M2 and M3 and, therefore, was (1→4)-β-linked d-mannan. The product formed in the presence of GDP-(14C) Man and unlabeled UDP-Gal gave M2, M3, monogalactosylmannobiose, monogalactosylmannotriose, digalactosylmannopentaose, plus other higher galactomanno-oligosaccharides, and could be confidently identified as galactomannan. In subsequent experiments, it was found that this stage of endosperm development with active galactomannan biosynthesis could be recognized reliably without flower tagging because the color of the testae of the developing L. japonicus seeds had just begun to change from green to brown.

Figure 1.

Dry weights of developing L. japonicus endosperms at various times after anthesis.

Figure 2.

Accumulation of neutral monosaccharide residues in total cell wall material from developing L. japonicus endosperms. □, Man. ▪, Gal. ♦, Glc. ▴, Ara.

Figure 3.

Autoradiogram of thin-layer chromatography (TLC)-separated endo-(1→4)-β-d-mannanase digestion products from radiolabeled polysaccharide products formed on incubating microsomal membranes from 28-DPA L. japonicus endosperms with GDP-(14C) Man (upper lane) and with GDP-(14C) Man plus unlabeled UDP-Gal (lower lane). M, Man; M2G, monogalactosylmannobiose; M3G, monogalactosylmannotriose; M5G2, digalactosylmannopentaose.

A Putative GMGT cDNA from Developing L. japonicus Endosperms

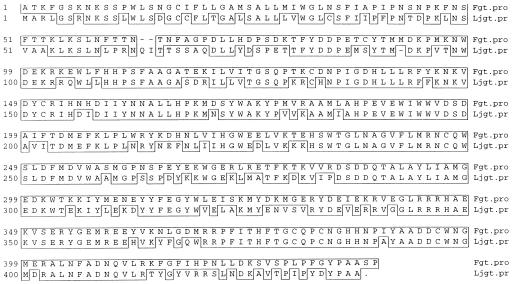

To facilitate the down-regulation of GMGT in L. japonicus endosperms by posttranscriptional silencing, it was desirable to have at least a partial sequence of an endogenous GMGT cDNA. Using single-stranded cDNA reverse transcribed from L. japonicus endosperm RNA isolated during active galactomannan biosynthesis as template, a PCR fragment (approximately 500 bp) was initially amplified using primers (5′ GA[A,C,G,T] TGG AT[A,C,G,T] TGG TGG GT[A,T] GA[C,T] 3′ and 5′ TGA GTG AAA GAG ACG TAC GGA 3′) that had been designed originally to the fenugreek GMGT sequence (Edwards et al., 1999) and sequenced. Application of 3′-RACE-PCR and 5′-RACE-PCR (Frohman and Martin, 1989) allowed the amplification and sequencing of the flanking regions toward the 3′and 5′ ends, respectively. The whole sequence, which included a complete open reading frame, was PCR amplified from the L. japonicus cDNA, cloned, and sequenced fully. The open reading frame (1,314 bp including the stop codon) encoded a 437-amino acid polypeptide, the sequence of which was closely similar to that of fenugreek GMGT. The two protein sequences (Fig. 4) showed 74.5% identity, and the cDNA sequences encoding the two open reading frames were 72.7% identical (sequences not shown; GenBank accession nos. for the fenugreek and L. japonicus sequences are AJ245478 and AJ567668, respectively).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the protein sequence of fenugreek GMGT (Edwards et al., 1999) with the open reading frame encoded by the putative GMGT cDNA from developing L. japonicus endosperm. The fenugreek sequence and identical amino acid residues in the L. japonicus sequence are boxed. Fgt.pro, Fenugreek GMGT protein sequence. Ljgt.pr, L. japonicus GMGT protein sequence.

The L. japonicus cDNA Encodes a Functional GMGT, and the Seeds from Some Primary L. japonicus Transgenics Transformed with L. japonicus GMGT cDNA in Sense and Antisense Orientations Have Endosperm Galactomannans with Altered Composition

Using Agrobacterium tumefaciens and a GPTV binary plasmid vector (Becker et al., 1992), L. japonicus hypocotyl explants were transformed with constructs carrying the full-length L. japonicus putative GMGT cDNA, inserted in sense and antisense orientations between the 2x35S promoter and the NOS terminator sequence. Geneticin G418-resistant plantlets regenerated from tissue culture were screened by genomic PCR using primers designed to the transgene and NOS terminator sequences. This showed that over 90% of the geneticin-resistant plantlets were transformed.

The control L. japonicus plantlets had no detectable GMGT activity (Reid et al., 2003) in their leaf tissues. This was as expected because galactomannan is present only in the cell walls of the seed endosperm. The primary transgenics that had been transformed with antisense GMGT constructs also showed no GMGT activity in their leaf tissues. On the other hand, some of the primary transgenics that had been transformed with the sense constructs did show GMGT activity in their leaves. This provided proof that the L. japonicus endosperm cDNA encoded a functional GMGT and confirmed the effectiveness of the 2x35S promoter in driving the expression of the constructs.

When plantlets regenerated from each independent geneticin-resistant callus were grown on to flowering (self-pollination) and seed formation, no unusual developmental phenotypes were observed for any of the plants. Seeds (T1 generation, self-pollination) were gathered from all plants, and total cell wall materials from their endosperms were isolated. Wall materials from batches of 10 endosperms from each plant were subjected to total acid hydrolysis and compositional analysis. As expected, all the samples hydrolyzed to Gal and Man, with only small amounts of other monosaccharides. The data were screened for variations in the quotient Man/Gal from the value of 1.2 to 1.3 that was found to be characteristic of the endosperms of control L. japonicus seeds. Of 30 presumed antisense lines screened, five variants were noted. The 30 presumed sense lines gave only two variants.

The leaves of six of the seven plants yielding seeds with variant Man/Gal values were PCR positive on screening with the primer pairs designed to the promoter and NOS terminator sequences, respectively. The seventh line, antisense line E9, was PCR negative using these primers. However, the use of the primer designed to the promoter sequence along with a primer designed to a sequence beginning 400 bp from the 5′ end of the antisense transgene gave amplification of DNA of the expected size (500 bp). However, no amplification was obtained using a primer designed to a sequence 450 bp further toward the 3′ end of the transgene sequence. Thus, antisense line E9 contained only a partial transgene sequence from which the 3′ end and the NOS terminator had been lost. The two sense lines that showed altered galactomannan structure did not have GMGT activity in their leaf tissues.

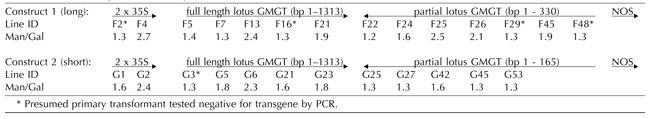

Sense/Antisense “Hairpin Loop” Constructs Give Greatly Increased Frequency of Occurrence of Changes in Galactomannan Structure

Following reports that sense/antisense constructs designed to give rise to self-complementary “hairpin” RNA were significantly more efficient at bringing about posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants than antisense or sense sequences (Smith et al., 2000), hybrid cDNAs were constructed. These comprised the full-length L. japonicus GMGT cDNA followed by an antisense sequence that was base complementary to the 5′ end of the GMGT sequence. Two constructs, differing in the length of the antisense component, were elaborated and used as above to obtain presumed primary L. japonicus transformants. Of the 26 presumed primary transformant lines that were obtained (14 transformed with the “long” construct and 12 with the “short” one), 21 were PCR positive on screening their leaf tissues using primer pairs designed to the 3′ end of the cDNA and the NOS terminator sequence. Of these, 15 exhibited Man/Gal values greater than 1.3 on screening their T1 generation seeds as above. The five PCR-negative lines had seeds with apparently unchanged Man/Gal values. The much higher frequency of altered Man/Gal values in the transgenic lines carrying sense-antisense GMGT constructs relative to those with simple sense and antisense GMGT constructs provided evidence that the compositional changes could be attributed to a process of posttranscriptional silencing of endogenous gene(s) that encoded GMGT in the developing seed endosperm, with consequent down-regulation of GMGT activity (Table II).

Table II.

Man/Gal values for hydrolysates of total cell wall materials from the endosperms of seeds (T1 generation) from presumed primary L. japonicus transformants with sense/antisense “hairpin loop” GMGT constructs under the control of the 2 x 35S promoter Batches of 10 endosperms were analyzed.

Segregation of the GMGT Transgene Constructs in Plants Grown from the Embryos of Individual T1 Generation Seeds in Relation to Galactomannan Composition in the Endosperm of the Same Seed

For a single transgene insertion into a diploid genome, Mendelian segregation in the T1 generation plant population resulting from self-pollination predicts 25% azygous individuals lacking the transgene, 50% heterozygous individuals, and 25% of individuals homozygous for the transgene. For a double independent insertion, Mendelian segregation rules predict a ratio of 1:14:1 between azygous individuals, various heterozygous combinations, and homozygous individuals. In a first set of experiments, T1 generation seeds from some of the sense and antisense lines with variant Man/Gal values (D33 and D41 sense lines; E4, E9, and E34 antisense lines) were germinated, and the young plants were screened by genomic PCR of leaf tissue for segregation of the transgene. The percentage (about 25%) of azygous individuals without the transgene was generally consistent with Mendelian segregation of a single transgene insert. However, one line (D33) showed a much lower number of azygous individuals, suggesting a double transgene insertion.

At the same time, further seeds from the five lines, plus a control line, were dissected, and the Man/Gal values for the endosperm galactomannans were determined for individual seeds. The results showed a surprisingly high degree of variability in Man/Gal value between individual seeds from each of the transgenic lines. However, the individual seeds from the control line exhibited Man/Gal values that fell within a narrow range (1.20-1.32; mean 1.26, sd 0.03; 21 seeds analyzed). All the transgenic lines included some individual seeds that had unchanged Man/Gal values of 1.2 or 1.3, but, with the exception of line D33 (probable double insert), the numbers of these individuals were greatly in excess of the numbers of azygous individuals predicted on the basis of Mendelian segregation. Thus, it seemed appropriate to attempt to correlate transgene inheritance in the embryo with galactomannan composition in the endosperm of the same seed.

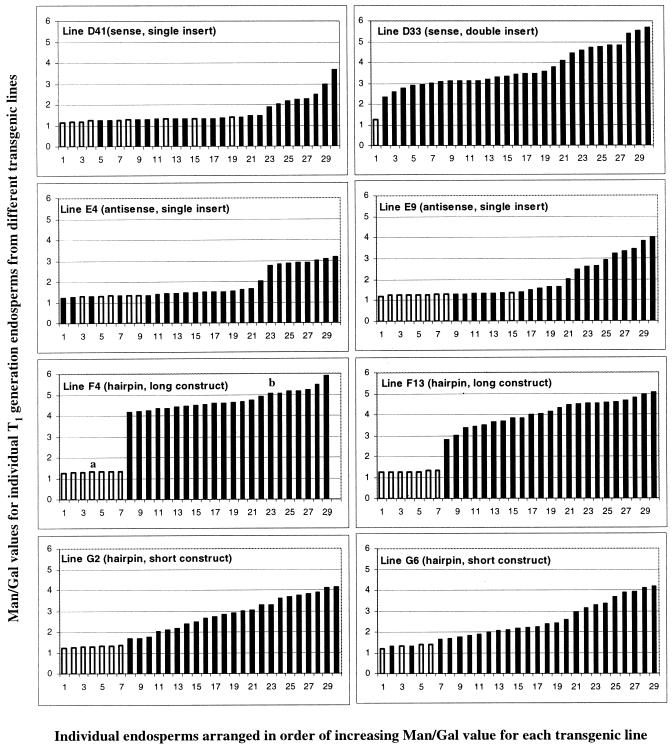

Individual seeds from four of the above sense and antisense lines—D41(sense, single transgene insertion), D33 (sense, probable double transgene insertion), E4, and E9 (antisense, single transgene insertion) were imbibed and then dissected carefully to remove the endosperm for analysis without damaging the embryo. Individual endosperms were processed to obtain total cell wall material for analysis. The corresponding embryos were germinated, and the young plants were analyzed by genomic PCR for the presence or absence of the transgene. For comparison, individual seeds from four of the “hairpin loop” lines—F4 and F13 (long construct) and G2 and G6 (short construct)—were processed in the same way.

The data (Fig. 5) confirmed that there was considerable variability in Man/Gal value between individual seeds from any one transgenic line and that the numbers of azygous (PCR-negative) individuals were consistent with Mendelian segregation of a single GMGT transgene insert for all lines except for D33. The segregation statistics for line D33 were again consistent with a double transgene insertion. The azygous individuals that had not inherited a GMGT transgene insert all had galactomannans with Man/Gal values in the range 1.2 to 1.4. The transgenic individual seeds from the sense and antisense lines that had a single transgene insert and from the short hairpin lines had galactomannans with Man/Gal values that ranged from 1.2 to 1.4 (indistinguishable from azygous individuals and controls) up to about 4. In contrast, the galactomannans in all the transgenic seeds from the long hairpin lines and from sense line D33 (probable double insert) had Man/Gal values that were strongly altered, ranging from 3 to 4 to almost 6.

Figure 5.

Man/Gal values for endosperm galactomannans in individual seeds (T1 generation, self-pollination) from various transgenic lines, in relation to transgene segregation in the corresponding embryos. Values marked with a white (□) bar relate to endosperms corresponding to azygous (PCR negative) embryos. Values marked with a filled (▪) bar relate to endosperms corresponding to transgenic (PCR positive) embryos. a, PCR result not available; assumed negative. b, PCR result not available; assumed positive.

Altered galactomannan composition required the inheritance of a GMGT transgene construct, and the constructs giving the greatest change in Man/Gal value for a single transgene insertion were of the hairpin type, which are known to bring about more marked posttranscriptional gene silencing than conventional antisense or sense ones (Smith et al., 2000). Thus, the data are again consistent with the hypothesis that the observed changes in galactomannan composition are brought about by down-regulation of endogenous GMGT activity in the developing L. japonicus endosperm, resulting probably from posttranscriptional gene silencing.

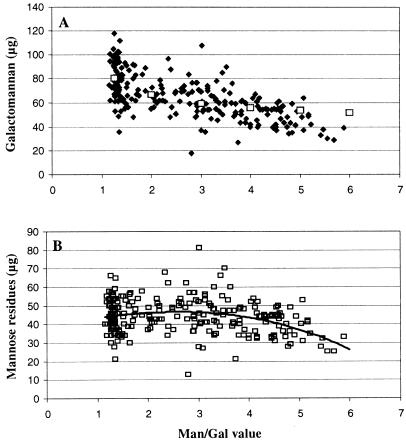

The Observed Increase in Man/Gal Value in Seeds from Transgenic Lines Is Attributable to Decreased Gal Substitution of a Constant or Decreased Amount of Mannan Backbone

The method used to analyze total endosperm cell wall material for Man/Gal value normally involved the addition of an internal standard during the hydrolysis procedure, allowing the total amount of galactomannan or of any individual monosaccharide residue per endosperm to be calculated. Thus, it was possible for all the single-seed analyses in Figure 5 to plot galactomannan amount against Man/Gal value. The graph (Fig. 6A) shows significant scatter, as is to be expected from a seed population with considerable variation in the size of individual seeds (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, there is a clear negative correlation between galactomannan amount and Man/Gal value. A negative correlation is to be expected if the observed increases in Man/Gal value arise from decreased Gal substitution of a mannan backbone, the amount of which remains constant. In this case, the expected relationship between Man/Gal value and galactomannan amount can be calculated and is indicated in Figure 6A. Clearly, there is good fit between the observed data points and the calculated line between Man/Gal = 1.2 and Man/Gal = 4. At the higher Man/Gal values (4 to the maximum observed value of 6), the decrease in galactomannan amount is greater than predicted, indicating that further decreases in Gal substitution are accompanied by a slight decrease in the amount of the mannan backbone. This is confirmed on plotting the absolute amounts of Gal and of Man residues per endosperm against Man/Gal value (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

A, Galactomannan amount in relation to Man/Gal values for individual seed endosperms from transgenic and azygous individuals (♦). Superimposed is the theoretical line that would be followed if increasing Man/Gal values were due exclusively to decreasing Gal substitution of a constant amount of mannan backbone. B, Amount of mannan backbone in relation to Man/Gal values for individual seed endosperms from transgenic and azygous individuals. Superimposed is a fitted third order polynomial trend line.

These analytical data show clearly that the observed changes in galactomannan composition arise from decreased galactosyltransfer against a background of constant or even somewhat decreased synthesis of mannan backbone. This was a direct indicator that the primary cause of the observed changes in galactomannan structure in the L. japonicus transgenic lines was decreased GMGT activity relative to MS in the developing seed endosperm.

In the Endosperms of Developing T2 Generation Seeds That Are Actively Synthesizing Galactomannan, GMGT Activity Is Lower Relative to MS in Transgenic Lines Than in Controls

Individual plants (T1 generation) from those transgenic lines exhibiting the largest increases in Man/Gal value were screened by PCR to ensure that they had inherited the transgene, and then allowed to self-pollinate and set seed. Pods were chosen at the time when galactomannan biosynthesis was at a maximum and endosperm homogenates were assayed for galactomannan biosynthesis in vitro, along-side controls. Because Gal incorporation from UDP-Gal in such systems is absolutely dependent on the simultaneous synthesis of mannan backbone from GDP-Man (Edwards et al., 1989;1992), the Man/Gal value of an in vitro galactomannan product formed using saturating concentrations of both sugar nucleotide substrates provides a measure of GMGT activity relative to MS. The data (Table III) showed clearly that GMGT activity was reduced relative to MS in those lines that exhibited increased Man/Gal values (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the amounts of reduction of GMGT activity observed in the different lines reflected the corresponding changes in Man/Gal value (compare Table III with Fig. 5). This provided a direct link between changed galactomannan structure and decreased GMGT activity in the developing seed endosperm.

Table III.

Maximum galactosyltransfer rates relative to mannan backbone synthesis during in vitro galactomannan synthesis catalyzed by developing endosperm homogenates from transgenic and control lines

| Line | Description | Galactosyltransfera (Backbone Synthesis = 100) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Stock plant, chosen randomly | 47, 48 |

| Line F29 (control) | Survived selection but PCR negative. Unchanged Man/Gal. | 48 |

| Line D6 (control) | Sense—GMGT activity expressed in leaf tissues. Unchanged Man/Gal. | 47, 46 |

| Line D33 | Sense—probable double insert (Fig. 5). | 22, 19 |

| Line E4 | Antisense (Fig.5). | 41 |

| Line F4 | Hairpin construct—long (Fig.5). | 25, 28 |

| Line G2 | Hairpin construct—short (Fig.5). | 31 |

Where two figures are entered, they were obtained using different enzyme preparations

DISCUSSION

With its endospermic seeds and high-Gal galactomannan, the model legume plant L. japonicus appeared a suitable system to explore the effect on galactomannan structure and/or amount of down-regulating GMGT in developing endosperms.

A cDNA clone that encoded a functional GMGT closely similar to that of fenugreek was obtained from developing L. japonicus endosperms that were actively synthesizing galactomannan. Some L. japonicus primary transgenic lines transformed with the L. japonicus GMGT cDNA in sense or antisense orientations or with sense-antisense “hairpin-loop” constructs under the control of the strong 2x35S promoter had seeds (T1 generation, self-pollination) that contained structurally altered endosperm galactomannans with increased Man/Gal values. The frequency of occurrence of the structural changes was very much greater with the “hairpin-loop” constructs. Transgene inheritance was consistent with Mendelian rules, and altered galactomannan structure was observed only in endosperms from seeds that had inherited a GMGT transgene construct. The observed increases in Man/Gal value were firmly attributed to decreased levels of Gal substitution of an unchanged or decreased amount of mannan backbone, and the endosperms of developing seeds from transgenic lines contained significantly less GMGT activity relative to MS than did controls. On the basis of these observations, it was concluded that the L. japonicus transgene constructs had brought about a measure of posttranscriptional silencing of gene(s) encoding endogenous GMGT(s) in the developing endosperm.

The current experimental model for galactomannan biosynthesis in vivo requires a functional interaction between MS and GMGT. The nascent mannan backbone is exposed to GMGT action as it emerges from the MS, whereas the transfer specificity of the GMGT (Edwards et al., 2002) determines the statistical distribution of Gal residues according to a second order Markov chain model (Reid et al., 1995; Edwards et al., 2002). In fenugreek, guar, and senna, the observed degree of Gal substitution of the primary product (Edwards et al., 1992) of galactomannan biosynthesis in vivo is very close to the theoretical maximum permitted by the four Markov probabilities scaled to let the highest one of the four equal 1.00 (Reid et al., 1995). A simple explanation of this observation is that there must be sufficient GMGT activity available at the site of synthesis always to ensure substitution of the nascent mannan chain to the maximum extent allowed by the Markov rules. In accordance, reduction of the activity of GMGT relative to MS would be expected to bring about a situation where there is insufficient GMGT to maintain maximal Gal substitution of the emerging mannan chain. This is fully consistent with our experimental findings.

We recently reported that tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) transgenic lines expressing fenugreek GMGT under the control of the strong 2x35S promoter had structurally altered galactomannans in their seed endosperm cell walls (Reid et al., 2003). The wild-type tobacco seed contains a (1→4)-β-linked mannan with a very low degree of Gal substitution (Man/Gal about 20). The Man/Gal values of the galactomannans in the transgenic seeds were remarkably constant at about 7.5, and it was speculated that this might represent the maximum degree of substitution achievable in the absence of any specific association between the tobacco MS and fenugreek GMGT proteins other than their proximity on the Golgi membrane. The much higher degrees of Gal substitution observed in the legume seed systems would then be the result of cooperativity between the MS and GMGT proteins, probably involving an enzyme complex. Our observation that decreasing Gal substitution beyond a limiting value (Man/Gal about 4-4.5) is accompanied by a decrease in mannan backbone may indicate that some specific association with GMGT protein is essential for MS activity in legume seed systems. Such an association would favor the synthesis of relatively highly Gal-substituted galactomannan products exhibiting the hydrophilic properties that have been shown to be of importance in the germinative strategy of legume seeds (Reid and Bewley, 1979).

The Man/Gal value at which backbone synthesis decreases (about 4) may be indicative of a further mechanism to prevent the synthesis of self-associated low-Gal galactomannan products. It is known that decreased Gal substitution in galactomannans leads to increased inter-chain association and decreasing water solubility and that Man/Gal values of about 4 correspond to Gal contents around which the water solubility of galactomannans becomes limited because of self-association of the mannan backbone. Furthermore, Man/Gal values of about 6, the maximum observed, correspond to Gal contents at which backbone interactions are strong enough to prevent dissolution of galactomannan in water even at 50°C (Mannion et al., 1992; Whitney et al., 1998). Thus, the biosynthetic enzyme system (or complex) may be inhibited by an accumulation of self-associated galactomannan at the site of synthesis, or self-associated galactomannan may bring biosynthesis to a halt indirectly by in some way preventing the subsequent process of secretion from the Golgi into the wall space.

Our failure to find any individual seeds containing galactomannans with Man/Gal values greater than 6, or seeds without galactomannan, is logical if suppression of galactomannan biosynthesis in the endosperm leads to failure of a seed to develop. Alternatively, the observed partial suppression of GMGT activity in L. japonicus endosperm may be the best achievable using our transgene constructs. Interestingly, we did not detect any differences in germination and seedling development between seeds containing Gal-reduced galactomannan and controls. However, differences in their responses to environmental challenge, notably drought stress, may yet emerge. For any given transgenic line, those seeds that had inherited a GMGT transgene construct showed wide variation in their galactomannan compositions (Fig. 5). This variation may reflect the complexity of transgene inheritance and expression in the triploid endosperm tissue in which maternal inheritance exerts greater influence.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of structural modification of a plant cell wall polysaccharide by down-regulating one of the Golgi-bound glycosyltransferases responsible for its polymerization. Down-regulating L. japonicus GMGT has resulted in modified galactomannans that are substantially less Gal substituted than controls. They exhibit Man/Gal values that range up to about 6. A similar range of Man/Gal values has been achieved in a commercial in vitro bioprocess for the enzymatic conversion of guar gum (Man/Gal = 1.6) to valuable low-Gal galactomannans (Bulpin et al., 1990). The process, which involves the action of a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)-expressed guar endosperm α-galactosidase on hydrated guar galactomannan, has significant costs. Attempts to achieve similar modification in planta by expressing senna α-galactosidase (Edwards et al., 1992) in transgenic guar (Joersbo et al., 1999) under the control of a wheat (Triticum aestivum) endosperm promoter had only limited success. The galactomannan products were only slightly modified (Man/Gal up to 1.8; Joersbo et al., 2001). The present results establish the feasibility of obtaining highly modified galactomannan products by the alternative strategy of down-regulating GMGT, the key enzyme regulating Gal substitution during galactomannan biosynthesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and General Methods

Media and antibiotics for plant tissue culture and transformation were from Duchefa (Haarlem, The Netherlands). GDP-(14C) Man was from DuPont-NEN (Stevenage, UK). Other specialized biochemicals were from Sigma (Poole, Dorset, UK). The preparation of Aspergillus niger endo-(1→4)-β-d-mannanase was the one used previously (Edwards et al., 1989; Reid et al., 2003). TLC separations of saccharides and the quantitative digital autoradiography of TLC-separated radiolabeled saccharides have been described (Reid et al., 2003). Endosperms from developing or mature, hydrated Lotus japonicus seeds were isolated under an MZ6 microscope (Leica Microsystems, Milton Keynes, UK). The colorless, gelatinous endosperm tissue located between the testa and embryo was easily detached and could be recovered quantitatively. The preparation of total cell wall material and its hydrolysis and compositional analysis have been described (Reid et al., 2003).

Galactomannan Biosynthesis in Developing L. japonicus Endosperms

Flowers were tagged at anthesis. Seeds (batches of 10) from developing pods of different ages taken from a given plant were dissected. The endosperms were either oven dried (110°C overnight) or used to prepare total cell wall material for compositional analysis.

Endosperms dissected from 200 seeds taken from 28-d pods (during intensive galactomannan deposition) were ground in a small all-glass Potter homogenizer (Jencons [Scientific] Ltd, Leighton Buzzard, UK) with isolation buffer (Edwards et al., 1989; 1 mL) containing 1 mm EDTA. The homogenate was used directly as enzyme for incubating with GDP-Man and UDP-Gal. Enzyme (50 μL) was incubated at 30°C exactly as described by Reid et al. (1995). Two series of incubations were carried out, one in the presence of GDP-Man (80 μm) labeled with 14C in the Man moiety and one with labeled GDP-Man (80 μm) plus unlabeled UDP-Gal (800 μm). Labeled polysaccharide products were isolated and fragmented using the A. niger endo-β-mannanase exactly as before (Reid et al., 1995).

Isolation and Characterization of a GMGT cDNA from Developing L. japonicus Endosperms

Seeds (500) taken from approximately 28-d pods (selected by appearance) were dissected. The endosperm tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground in the frozen state using a mortar and pestle with liquid nitrogen. As for fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) endosperms (Edwards et al., 1999), RNA was prepared from the galactomannan-rich tissue using the method of Lopez-Gomez and Gomez-Lim (1992) and used in RT-PCR and RACE protocols (Frohman and Martin, 1989). Amplified bands were cloned as before (Edwards et al., 1999). Sequences were compared using Lasergene software (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI).

Culture and Transformation of L. japonicus

Seeds of L. japonicus “Gifu” (accession no. B-129) were originally obtained from Professor Jens Stougaard (Laboratory of Gene Expression, Department of Molecular Biology, University of Aarhus, Denmark). Plants were grown in 10-cm-diameter pots in a commercial compost (Levington Multi-purpose, The Scotts Company, Godalming, UK) under a 16-h-light/8-h-dark regime at 21°C. The light intensity at table level was 240 μmol m-2 s-1 photosynthetically active radiation. Mineral nutrition was with “Phostrogen” (pbi Home and Garden, Enfield, UK) applied monthly. To ensure self-pollination and to prevent the escape of seeds, entire plants were enclosed in a transparent cellophane bag.

A transformation vector was used that placed L. japonicus GMGT cDNA constructs (sense, antisense, and sense/antisense “hairpin loop”) between the double 35S promoter from cauliflower mosaic virus (Kay et al., 1987) and the NOS poly(A+) signal in the plant transformation vector pGPTV-KAN (Becker et al., 1992). The plasmid was amplified in Escherichia coli and introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA 4404. Transformation and regeneration of L. japonicus was carried out exactly as described by Thykjær et al. (1998) with the exception that no attempt was made to excise individual transgenic calli from a single hypocotyl explant. The independence of transformation events was assured by processing only one regenerated plantlet from each explant. Geneticin (G418) was the antibiotic used for selection. Control plants were regenerated from tissue culture without antibiotic selection.

Screening of L. japonicus Transformants

PCR screening of putative transformants was carried out using genomic DNA isolated (Edwards et al., 1991) from leaf tissues as template and primer pairs designed either to the promoter and terminator sequences or to one of these and the L. japonicus cDNA sequence.

Leaf tissues from L. japonicus transgenics carrying full-length sense GMGT constructs and controls were screened for GMGT activity as described previously for tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) transgenics carrying fenugreek GMGT constructs (Reid et al., 2003).

Screening of transformants for altered galactomannan composition in the endosperms of their (T1 generation) seeds was carried out by preparing total cell wall material from batches of 10 dissected endosperms, hydrolyzing it, and subjecting the hydrolysate to compositional analysis. Before dissection, the seeds were swollen in water at 100°C for 5 min.

Correlating Transgene Segregation and Endosperm Galactomannan Composition in the Same Seed

Seeds were lightly scarified (fine sand paper), surface sterilized (hypochlorite), and allowed to hydrate overnight at 4°C. Each seed was dissected carefully under aseptic conditions. Embryos were transferred to petri dishes containing one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium with one-half-strength B5 vitamins, 1% (w/v) Suc, and 0.4% (w/v) Gelrite for germination. When the plantlets were 3 to 4 weeks old, leaf tissue was sampled for PCR screening. The corresponding endosperms were used individually to prepare total cell wall materials that were hydrolyzed quantitatively with addition of Fuc as internal standard.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Jens Stougaard (Laboratory of Gene Expression, Department of Molecular Biology, University of Aarhus, Denmark) for supplying seeds of L. japonicus and for his advice on transformation and tissue culture. We would like to thank Dr Judith Webb (Institute of Grassland and Environmental Research, Aberystwyth, UK) for sharing her wide experience of the L. japonicus system; she has been a constant source of valuable advice. As part of her undergraduate student project, Cathlene Eland (University of Stirling, Stirling, UK) helped us to clone and sequence the L. japonicus GMGT cDNA. Similarly, Alan Hiddleston (University of Stirling, Stirling, UK) helped us acquire data on galactomannan formation in developing L. japonicus seeds. Their contributions are gratefully acknowledged.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.103.029967.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (UK; research grant).

References

- Becker D, Kemper E, Schell J, Masterson R (1992) New plant binary vectors with selectable markers located proximal to the left T-DNA border. Plant Mol Biol 20: 1195-1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulpin PV, Gidley MJ, Jeffcoat R, Underwood DR (1990) Development of a biotechnological process for the modification of galactomannan polymers with plant α-galactosidase. Carbohydr Polymers 12: 155-168 [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JM, Reid JSG (1982) Galactomannan formation and guanosine 5′-diphosphate-mannose: galactomannan mannosylyransferase in developing seeds of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L., Leguminosae). Planta 155: 105-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dea ICM, Morrison A (1975) Chemistry and interactions of seed galactomannans. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem 31: 241-312 [Google Scholar]

- Dea ICM, Morris ER, Rees DA, Welsh EJ, Barnes HA, Price J (1977) Associations of like and unlike polysaccharides: mechanism and specificity in galactomannans, interacting bacterial polysaccharides and related systems. Carbohydr Res 57: 249-272 [Google Scholar]

- Edwards K, Johnstone C, Thompson C (1991) A simple and rapid method for the preparation of genomic DNA for PCR analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 16: 1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M, Bulpin PV, Dea ICM, Reid JSG (1989) Biosynthesis of legume seed galactomannans in vitro. Planta 178: 41-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M, Scott C, Gidley MJ, Reid JSG (1992) Control of mannose/galactose ratio during galactomannan formation in developing legume seeds. Planta 187: 67-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ME, Dickson CA, Chengappa S, Sidebottom C, Gidley MJ, Reid JSG (1999) Molecular characterisation of a membrane-bound galactosyltransferase of plant cell wall matrix polysaccharide biosynthesis. Plant J 19: 691-697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ME, Marshall E, Gidley MJ, Reid JSG (2002) Transfer specificity of detergent-solubilized fenugreek galactomannan galactosyltransferase. Plant Physiol 129: 1391-1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohman MA, Martin GR (1989) Rapid amplification of cDNA ends using nested primers. Techniques 1: 163-170 [Google Scholar]

- Handberg K, Stougaard J (1992) Lotus japonicus, an autogamous, diploid legume species for classical and molecular genetics. Plant J 2: 487-496 [Google Scholar]

- Joersbo M, Brunstedt J, Marcussen J, Okkels FT (1999) Transformation of the endospermous legume guar (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L.) and analysis of transgene transmission. Mol Breed 5: 5211-5529 [Google Scholar]

- Joersbo M, Marcussen J, Brunstedt J (2001) In vivo modification of the cell wall polysaccharide galactomannan of guar transformed with a α-galactosidase gene cloned from senna. Mol Breed 7: 211-219 [Google Scholar]

- Kay R, Chan A, Daly M, McPherson J (1987) Duplication of CAMV-35S promoter sequences creates a strong enhancer for plant genes. Science 236: 1299-1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Gomez R, Gomez-Lim MA (1992) A method for extracting intact RNA from fruits rich in polysaccharides using ripe mango mesocarp. HortScience 27: 440-442 [Google Scholar]

- Mannion RO, Melia CD, Launay B, Cuvelier G, Hill SE, Harding SE, Mitchell JR (1992) Xanthan locust bean gum interactions at room-temperature. Carbohydr Polymers 19: 91-97 [Google Scholar]

- McCleary BV (1979) Modes of action of β-d-mannanase enzymes of diverse origin on legume seed galactomannans. Phytochemistry 18: 757-763 [Google Scholar]

- McCleary BV, Matheson NK (1983) Action patterns and substrate-binding requirements of β-mannanase with mannosaccharides and mannan-type polysaccharides. Carbohydr Res 119: 191-219 [Google Scholar]

- Meier H, Reid JSG (1982) Reserve polysaccharides other than starch in higher plants. In FA Loewus, W Tanner, eds, Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology, New Series 13A: Plant Carbohydrates I. Springer, Berlin, pp 418-471

- Nadelmann H (1890) Über die schleimendosperme der leguminosen. Jahrb Wiss Bot 21: 1-83 [Google Scholar]

- Reid JSG (1985) Cell wall storage carbohydrates in seeds: biochemistry of the seed “gums” and “hemicelluloses.” Adv Bot Res 11: 125-155 [Google Scholar]

- Reid JSG, Bewley JD (1979) A dual role for the endosperm and its galactomannan reserves in the germinative physiology of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L), an endospermic leguminous seed. Planta 147: 145-150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JSG, Edwards M (1995) Galactomannans and other cell wall storage polysaccharides in seeds. In AM Stephen, ed, Food Polysaccharides and Their Applications. Marcel Dekker, New York, pp 155-186

- Reid JSG, Edwards M, Gidley MJ, Clark AH (1995) Enzyme specificity in galactomannan biosynthesis. Planta 195: 489-495 [Google Scholar]

- Reid JSG, Edwards ME, Dickson CA, Scott C, Gidley MJ (2003) Tobacco transgenic lines that express fenugreek galactomannan galactosyltransferase constitutively have structurally altered galactomannans in their seed endosperm cell walls. Plant Physiol 131: 1487-1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson PH, Norton IT (1998) Gelation behaviour of concentrated locust bean gum solutions. Macromolecules 31: 1575-1583 [Google Scholar]

- Smith NA, Singh SP, Wang M-B, Stoutjesdijk PA, Green AG, Waterhouse PM (2000) Total silencing by intron-spliced hairpin RNAs. Nature 407: 319-320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thykjær T, Schauser L, Danielsen D, Finneman J, Stougaard J (1998) Transgenic plants: Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of the diploid legume Lotus japonicus. In JE Celis, N Carter, T Hunter, D Shotton, K Simon, JV Small, eds, Cell Biology: a Laboratory Handbook, Ed 2, Vol 3. Academic Press, New York, pp 518-525 [Google Scholar]

- Whitney SEC, Brigham JE, Darke AH, Reid JSG, Gidley MJ (1998) Structural aspects of the interaction of mannan-based polysaccharides with bacterial cellulose. Carbohydr Res 307: 299-309 [Google Scholar]