Abstract

Cholinergic receptors have been implicated in schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease. However, to better target therapeutically the appropriate receptor subsystems, we need to understand more about the functions of those subsystems. In the current series of experiments, we assessed the functional role of M1 receptors in cognition by testing M1 receptor-deficient mice (M1R−/−) on the five-choice serial reaction time test of attentional and response functions, carried out using a computer-automated touchscreen test system. In addition, we tested these mice on several tasks featuring learning, memory and perceptual challenges. An advantage of the touchscreen method is that each test in the battery is carried out in the same task setting, using the same types of stimuli, responses and feedback, thus providing a high level of control and task comparability. The surprising finding, given the predominance of the M1 receptor in cortex, was the complete lack of effect of M1 deletion on measures of attentional function per se. Moreover, M1R−/− mice performed relatively normally on tests of learning, memory and perception, although they were impaired in object recognition memory with, but not without an interposed delay interval. They did, however, show clear abnormalities on a variety of response measures: M1R−/− mice displayed fewer omissions, more premature responses, and increased perseverative responding compared to wild-types. These data suggest that M1R−/− mice display abnormal responding in the face of relatively preserved attention, learning and perception.

1. Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that our attempts at developing pro-cholinergic treatments for diseases affecting cognition – schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease, to name just a few (Bartus et al., 1982; Coyle et al., 1983; Eglen et al., 1999; Felder et al., 2000; Friedman, 2004; Wess, 2004; Youdim and Buccafusco, 2005) -- have been met with limited success. One possible reason for this lack of success is our lack of understanding of the specific functional roles of the various subtypes of cholinergic receptors (Gainetdinov and Caron, 1999). To target treatments to the critical cholinergic subsystem associated with disease, we must first understand the functions of these subsystems. With respect to diseases involving changes in cognition, many authors have emphasized specifically the importance of the muscarinic (M1 – M5) receptor subsystem (Bymaster et al., 2002; Langmead et al., 2008; Wess, 2004). In the present study we focused on the functional role of the M1 receptor, as M1 receptors have been repeatedly implicated in normal cognition, as well as in all of the diseases mentioned above (Dean et al., 2003; Fisher, 2008; Wess et al., 2007).

One aspect of cognitive function with which the cholinergic system has been repeatedly associated is attention (Passetti et al., 2000; Robbins, 1997; Sarter and Bruno, 2000), which can effectively be assessed in rodents using the 5-choice serial reaction time task (5-CSRTT). This task provides measures of sustained attentional function, and also measures of abnormal responding, for example premature and perseverative responses (thought to model impulsivity and compulsivity, respectively) (Carli et al., 1983; Robbins, 2002). Non-selective muscarinic receptor antagonists impair attentional function in rodents performing the 5-CSRTT when given either systemically (Humby et al., 1999; Jones and Higgins, 1995; Mirza and Stolerman, 2000; Pattij et al., 2007) or when infused directly into prefrontal cortex (Chudasama et al., 2004; Dalley et al., 2004; Muir et al., 1996). However, little is known about which specific muscarinic receptor subtypes are involved in this task. As the M1 receptor is the predominant muscarinic receptor in cortex (Flynn et al., 1995; Levey et al., 1991), we speculated that this receptor might play an important role in attention as measured by the 5-CSRTT.

M1 knockout (M1R−/−) mice are an ideal model for investigating the role of these receptors in cognition, as there is a paucity of agents with which to target these receptors selectively, and the knock-out mice do not show any gross behavioral or morphological abnormalities, making them well-suited to cognitive testing (Wess, 2004; Wess et al., 2007). Furthermore, several studies have indicated that disruption of one specific muscarinic receptor gene does not have major effects on the levels of the four remaining muscarinic receptors (Hamilton et al., 1997). In the present study, therefore, we trained M1R−/− mice and wild-type (M1R+/+) controls on a touchscreen version of the 5-CSRTT, and assessed their performance under a number of behavioral challenge conditions, as well as on several additional tests of cognition using the same touchscreen apparatus, and on a spontaneous object recognition test using 3-dimensional objects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment 1: 5-CSRTT

In experiment 1 we examined the performance of M1R−/− mice and wild-type controls (M1R+/+) in a touchscreen version of the 5-CSRTT. This task has been indispensable for investigating the neuropsychological mechanisms involved in diseases and disorders that manifest attentional dysfunction (e.g., attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), AD, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, and addiction) (Carli et al., 1983; Chudasama and Robbins, 2004; Dalley et al., 2007; Dalley et al., 2001; Dalley et al., 2005; Granon et al., 2000; Muir et al., 1992; Puumala et al., 1996). The 5-CSRTT is an analogue of the continuous performance test in humans (Robbins, 2002). The 5-CSRTT measures subjects’ sustained visual attention and requires subjects to scan an array for the location of brief visual targets, presented over discrete trials. In the present study, attentional processing was examined in M1R+/+ and M1R−/− mice in the touchscreen 5-CSRTT. Group performance was compared at baseline using two different task challenges which were introduced to further elucidate the role of M1 receptors in attention. In the first challenge the stimulus duration was shortened from 2 s to 1.5 s and 0.8 s. Two testing sessions were given with a 1.5 s stimulus duration, followed by two with a 0.8 s stimulus duration. For the second task challenge, a shorter ITI (2 s) was enforced and mice were examined in the 5-CSRTT using a 2 s stimulus duration, and were tested for 2 h sessions (or 200 trials, whichever occurred first). By using a longer testing session and a shorter ITI (‘high event rate’), requires increased vigilance and perseverance to complete trials, and has been used as a measure of sustained attention (Dalley et al., 2004).

2.1.1. Subjects

Mice with targeted deletions of the M1 receptor (M1R−/−) (genetic background: 129/SvEv × CF1) were generated as described previously (Fisahn et al., 2002; Hamilton et al., 1997) and backcrossed onto C57BL/6 mice (Taconic, Germantown, New York) for at least 10 generations. Ten male M1R−/− and ten C57BL/6 female mice were shipped to the University of Cambridge for breeding the first generation of heterozygous (M1R+/−) mice. To avoid abnormalities resulting from genotypic differences in neonatal environment (Holmes et al., 2005), M1R−/−, M1R+/−, and wild-type (M1R+/+) mice were generated from M1R+/− × M1R+/− matings. Thus, the generation of M1R +/− was then bred together to produce a second generation of mice (M1R+/+, M1R+/−, and M1R−/−). Only M1 receptor deficient mice (M1R−/−) and wild-type mice (M1R+/+) male mice were used in behavioral studies; the heterozygous males and females were used for additional breeding.

Mice were genotyped at weaning (3 weeks). Cohort 1 (5-CSRTT mice) contained 6 M1R+/+ and 9 M1R−/− male mice; cohort 1 mice were tested in a brief oddity pilot experiment, not in the touchscreen and using three dimensional objects, prior to testing in the touchscreen 5-CSRTT. Mice were housed in groups of 2–10, in a room with a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights off at 7:00 P.M.). All behavioral testing was conducted during the light phase of the cycle. Mice were maintained on a restricted diet and kept at or above 85% of free-feeding body weight during behavioral testing. Mice were fed wet food mash in home cages following behavioral testing. Water was available ad libitum throughout the experiment. All experimentation was conducted in accordance with the United Kingdom Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986).

2.1.2. Apparatus

Testing was conducted in a touchscreen-based automated operant system for mice. The apparatus consisted of a standard modular testing chamber housed within a sound- and light-attenuating box (40 × 34 × 42 cm) (Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, Vermont). The inner operant chamber consisted of a metal frame, clear Perspex walls, and a stainless steel grid floor. The box was fitted with a fan (for ventilation and masking of extraneous noise) and a pellet receptacle (magazine), which was illuminated by a 3W light bulb and fitted with a photocell head entry detector attached to 14 mg pellet dispenser (situated outside of the box). A 3W houselight and tone generator (Med Associates) were fitted to the back wall of the chamber. Behavioral testing programs were controlled with a computer software program (‘MouseCat’, L.M. Saksida) written in Visual Basic (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

At the end of the box, opposite the magazine was a flat-screen monitor equipped with an infrared touchscreen (16 cm high and 21.20 cm wide) (Craft Data Limited, Chesham, UK) mediated by ELO touchscreen software (ELO Touchsystems Inc.). Since the touchscreen uses infrared photocells, the mouse was not required to exert any pressure on the monitor screen in order for a nose-poke to be detected. Furthermore, black Perspex ‘masks’ with response windows were placed over the screen, through which the mouse could make a nosepoke toward the screen. The 5-CSRTT mask contained five response windows (2.2 cm high and 1.7 cm wide) which were spaced 1.8 cm from one another and located 3.5 cm from the sides of the mask and 1.5 cm from the bottom of the mask.

2.1.3. 5-CSRTT pretraining

Prior to testing, mice were handled daily for one week, and body weights were closely monitored. During the first session, mice were habituated to the testing chamber for two consecutive daily sessions. The houselight remained on during the entire session and food pellets were placed in the magazine and the mice were left in the testing chamber for 15 minutes. After the habituation stage, mice were trained to collect pellets delivered under a variable interval 30 s schedule, which coincided with illumination of the magazine light and presentation of a tone. Stimuli (white squares) were presented (one per trial) for 30 s on the touchscreen located on one of the five response windows. A single reward pellet was delivered immediately following stimulus offset. If the mouse touched the stimulus, the stimulus immediately disappeared from the touchscreen and the mouse was rewarded with the tone, magazine light, and three food pellets. Completion of this stage was not dependent on the mouse touching the stimuli on the screen; therefore, the mice were removed from the testing chamber after the 30 min session, regardless of the number of trials completed.

The next training session required the mice to respond to the white square presented on the touchscreen in order to receive a pellet reward. On each trial, a white square was shown in one of the five response windows, and remained on the screen until the mouse responded to the stimulus. The mouse was rewarded with a pellet, tone, and illumination of the magazine light, followed by a 5 s ITI after which the next trial commenced, and a new white square was presented on the touchscreen. Once a mouse successfully completed 30 trials in a 1 h session, the mouse was then required to initiate trials in the next training stage. During this stage, after collecting a reward following a response to the stimulus, and exiting the food magazine, the mouse was required to again poke their head in the magazine, in order for the next stimulus array to be presented on the screen. Once the mouse was successfully initiating trials and had completed 30 trials in 1 h, the experiment proper began.

2.1.4. 5-CSRTT

After successful completion of pretraining, mice were trained on 5-CSRTT. This task has been traditionally tested in rodents using a 5- or 9-hole operant box (Bari et al., 2008; Carli et al., 1983; Robbins, 2002). In this version of the 5-CSRTT, one side of the operant box is a curved aluminum wall containing either 5 or 9 square holes, and the opposite side of the operant chamber in a straight wall which contains a food magazine (used for food collection and initiation).

For the computer touchscreen version of the 5-CSRTT, mice were trained to respond to brief flashes of light pseudorandomly displayed in one of the five spatial locations in the same manner as the 5- or 9-hole version of 5-CSRTT. A trial was initiated after the mouse made a nose-poke to the magazine located at the back of the chamber, which started a 5 s ITI, in which the mouse scanned the five locations. At the end of the ITI, a flash of light was presented pseudorandomly in one of the five locations. The mouse was required to respond to the flash of light within a limited period (limited hold = 5 s). A correct response was recorded when the mouse made a nose-poke to the correct location either while the stimulus was presented or during the limited-hold period. A correct response resulted in disappearance of the stimulus and presentation of the pellet and tone, and illumination of the food magazine. A failure to respond to the correct location while the square was lit or within the 5 s limited hold was recorded an incorrect response and resulted in a time-out period where the houselight and magazine were extinguished. A failure to respond to any locations (correct or incorrect) during stimulus presentation or within the 5 s limited hold period was recorded as an omission. A response made before the presentation of a lit stimulus location, during the 5 s ITI, was recorded as a premature response. Additional responses were also recorded and included: perseverative correct same, perseverative correct different, perseverative incorrect, and perseverative premature (all described in the section below, data analysis).

The limited hold, ITI, and time-out remained at 5 s throughout training. At the beginning of training, the stimulus duration was set to 32 s. When a subject produced two consecutive sessions at performance levels (= 50 trials, > 80 % accuracy, and < 20 % omissions) the stimulus duration was reduced in the following pattern: 22, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1.8, 1.6 s. Not all mice could perform well (= 50 trials, > 80 % accuracy, and < 20 % omissions) when using shorter than a 2 s stimulus duration (three M1 receptor-deficient mice and two wild-type were able to perform at high performance levels at 1.8s, and one wild-type mouse was able to perform well at 1.6 s. Therefore, all mice were re-baselined using a 2 s stimulus duration for 7 sessions, before the task challenges began. The first task challenge was shortening the stimulus duration from 2 s to 1.5 s and 0.8 s. Two testing sessions were given with a 1.5 s stimulus duration, followed by two with a 0.8 s stimulus duration. For the second task challenge, mice were first re-baselined for three sessions and then were given three sessions using a shorter 2 s ITI, a 2 s stimulus duration, and were tested for 2 h sessions (or 200 trials, whichever occurred first).

2.1.5. Data analysis

Percentages were calculated for the following responses: correct (accuracy: correct trials divided by correct plus incorrect trials), omissions (omitted trials divided by total trials), premature (premature trials divided by total trials). Perseverative responses were broken down into: perseverative correct same (the mean number of perseverative responses made following a response to a correct location, to that same location), perseverative correct different (the mean number of perseverative responses made following a response to a correct location, to any location other than the correct location), perseverative incorrect (the mean number of perseverative responses, to any location, made following a response to an incorrect location), and perseverative premature (the mean number of perseverative responses made following a premature response). Perseverative responses were calculated as the group mean number of perseverative responses (Correct Same, Correct Different, Incorrect, and Premature). These measures reflect the number of perseverative responses per initial response. Thus, if a mouse’s Perseverative Incorrect score were 3, that would mean that incorrect responses were followed by an average of 3 further, perseverative responses. Reaction time and magazine latency were analyzed for correct responses only.

Means for the first task challenge (stimulus duration) were submitted to two-way ANOVA with the within subjects repeated measure for stimulus duration and the between subjects factor of group. Means of paired-samples t-tests were used for post-hoc analyses of within-subject effects and group effects were analyzed with independent samples t-tests. Means for the second task challenge (2 s ITI, 2 s stimulus duration, and 200 trials/2 h session) were submitted to independent samples t-tests. Only the first two trial bins (1–25 and 26–50) were analyzed since all mice completed all trials within 2 hours. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted using all 8 bins (Karlsson et al., 2008). All statistical analyses were conducted with a significance level of p = 0.05.

2.2 Experiment 2: Visual Discrimination

In experiment 2 a new cohort of M1R+/+ and M1R−/− mice were tested in an established two-choice visual discrimination touchscreen task using shape stimuli (Bussey et al., 2008; Bussey et al., 2001; Morton et al., 2006). Following acquisition of the initial visual discrimination, stimulus contingencies were reversed, and the previously rewarded stimulus (S+) became the unrewarded stimulus (S−), and the unrewarded stimulus (S−) was now the rewarded stimulus (S+).

2.2.1. Subjects

Cohort 2 contained 7 M1R+/+ and 9 M1R−/− male mice that were aged 12 to 16 weeks at the start of behavioral testing. Cohort 2 was obtained, housed, and fed in a similar manner to cohort 1.

2.2.2. Apparatus

Testing was conducted in the touchscreen-based automated operant system for mice (described previously [see 2.1.2. “Apparatus”]). The visual discrimination and reversal mask (11.8 cm high and 22.8 cm wide) had two response windows (6.3 cm high and 4.7 cm wide), which were spaced 0.5 cm from one another and located 6.4 cm from the sides of the mask and 1.5 cm from the bottom of the mask.

2.2.3. Pretraining

Habituation and pretraining for experiment 2 was identical to the experiment 1 (see experiment 1 ‘pretraining’ section for more details), except, instead of white squares appearing on the screen, training stimuli (40 stimuli varying in brightness, shape, and pattern) were presented (one per trial) for 30 s on the touchscreen located on one of the two response windows. A large set of training stimuli were used to minimize subsequent generalization from a particular stimulus feature. Furthermore, a final training stage, punishment for incorrect responses (responses to a window in which no stimulus was displayed) and a correction procedure were introduced. A stimulus was presented in one of the three response windows and the mouse was required to nose-poke the stimulus. Correct responses were followed by stimulus offset, presentation of the pellet, tone, and illumination of the food magazine (followed by a 20 s ITI). Incorrect responses resulted in the houselight being extinguished, disappearance of the stimulus, and a time-out period of 5 s, which was followed by the 20 s ITI. A correction procedure was implemented whereby the trial was repeated until the mouse made a correct choice. Once the mouse completed this stage at 70 % correct (21/30) over two consecutive sessions, mice began the visual discrimination task.

2.2.4. Visual discrimination task

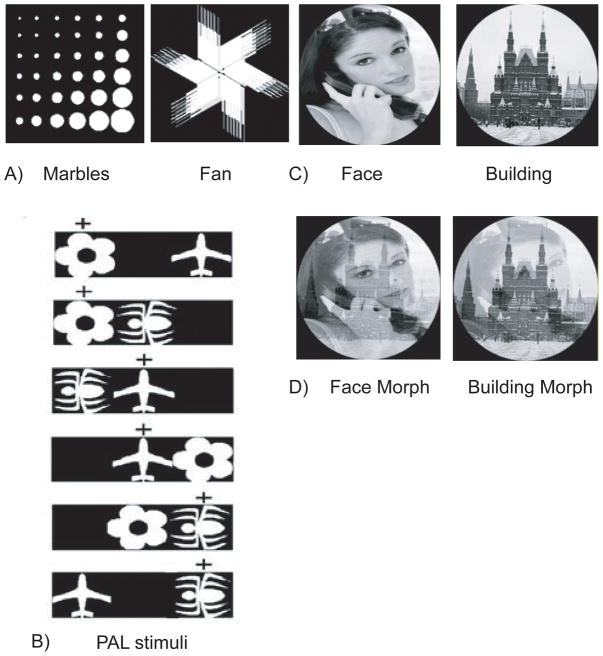

After successful competition of pretraining, mice were trained on a visual discrimination task. At the beginning of a session, the mouse was required to initiate the first trial. Then, a pair of stimuli (fan and marbles) (see Figure 1A) appeared on the screen (one stimulus was located in each response window). One stimulus was correct (S+) (marbles) and the other (fan) was incorrect (S−). The location of the S+ was determined pseudorandomly and the maximum number of times the S+ could appear in the same response window was two times consecutively, in order to minimize side biases. A nose-poke to the S+ resulted in a tone, magazine light, and reward pellet. A nose poke to the S− resulted in a 5 s time-out period, followed by a correction procedure. Chance performance in the visual discrimination task is 50%. The ITI during the task was fixed at 20 s. Each mouse was required to complete 30 trials within a 1 h session. Mice were required to complete all 30 trials with 80 % accuracy (24/30 or better) over three consecutive days to reach criterion.

Figure 1.

A) Illustration of the shape stimulus pair, marbles and fan, used in the visual discrimination task (experiment 1). For the initial visual discrimination the S+ was marbles, and the S− was fan. For the reversal, S+ was fan and the S− was marbles. B) Figure depicting the six possible trial types that could occur during the PAL task (experiment 2). Flower is the S+ when it is located in the left location, plane is the S+ when located in the middle location, and spider is the S+ when located in the right location. C) Illustration of the photographic stimulus pair, face and building, used in the visual discrimination task (experiment 3). For the initial visual discrimination the S+ was face, and the S− was building. For the reversal, building was the S+ and face was the S−. D) Illustration of the morphed photographic stimulus pair, face and building (experiment 4). For the morph discrimination, the S+ was building, and the S− was face.

After a mouse reached criterion, testing of that mouse stopped. After all mice reached criterion (all mice reached criterion within 25 sessions), mice were re-baselined on the task for 5 days, and then the reversal discrimination commenced. During the reversal, the S+ (marbles) now became the S−, and the S− (fan), now became the S+. Mice were tested on the reversal discrimination for 20 sessions.

2.2.5. Data Analysis

Group means of the number of sessions to criterion for the initial discrimination (S+: marbles and S−: fan) was analyzed using an independent samples t-test. Group means of the reversal were submitted to a two-way ANOVA where the first factor was the between subjects factor of group and the second factor was the within-subjects factor of session. Paired-samples t-tests were used for post hoc analyses of within-subject effects. All statistical analyses were conducted with a significance level of p = 0.05.

2.3. Experiment 3: Paired-Associates Learning

In experiment 3, cohort 2 mice were examined in the automated touchscreen PAL task (Talpos et al., 2009), which measures visuospatial abilities. Although systemic post-acquisition administration of M1 antagonists in normal mice impairs PAL performance (Bartko et al., 2011), the role of M1 receptors in PAL during acquisition has not been previously examined.

2.3.1. Subjects

Cohort 2 mice were tested in experiment 3. One knockout mouse died after experiment 2, therefore, 7 M1R+/+ and 8 M1R−/− were tested.

2.3.2. Apparatus

Testing was conducted in the touchscreen-based automated operant system for mice (described previously (see 2.1.2. “Apparatus”). The PAL mask (11.8 cm high and 22.8 cm wide) contained three response windows (5.0 cm high and 5.0 cm wide) which were space 0.8 cm from one another and located 3.0 cm from the sides of the mask and 1.7 cm from the bottom of the mask.

2.3.3. PAL touchscreen task

Since the mice were already habituated to touchscreen testing, completion of a PAL-specific pretraining program was deemed unnecessary. Therefore, five days after finishing the visual discrimination/reversal task, mice were tested on the PAL task.

2.3.4. PAL task

At the beginning of a session, the mouse was required to initiate the first trial. Then, a pair of stimuli would appear on the screen (in two of the three locations: left, middle, and right; one stimulus was the correct S+ and the other was the incorrect S−. There were six possible trial types (See Figure 1B) and three different stimuli were used (flower, plane, and spider). Within the six trial types, the flower was rewarded only when presented in the left location, the plane was rewarded only when presented in the middle location, and the spider was rewarded only when presented in the right location. Therefore, the mouse was required to learn the paired-associate of stimulus and location. A nose-poke to the correct S+ resulted in a tone, magazine light, and reward pellet. Incorrect responses resulted in a 5 s time-out period, followed by correction procedure. Nose-pokes to response windows in which no stimulus was presented were ignored. The ITI during the task was fixed at 20 s. In a testing session, mice were given 1 h to complete 36 trials (each trial type could occur six times and the maximum number of times a particular trial type could occur consecutively was twice). All mice completed 50 sessions of the PAL task.

2.3.5. Data analysis

Group means of accuracy (percent correct) were submitted to a two-way ANOVA where the first factor was the between-subjects factor of group and the second factor was the within-subjects factor of session. All statistical analyses were conducted with a significance level of p = 0.05.

2.4. Experiment 4: Visual discrimination task with photographic stimuli

After acquisition of the PAL task, cohort 2 mice were tested on a more difficult visual discrimination task, containing photographic stimulus pairs instead of shape stimulus pairs, since preliminary data has shown that that M1 receptors in perirhinal cortex are necessary for complex perceptual processing (Bartko et al., 2008).

2.4.1. Subjects

Cohort 2 mice were tested in experiment 4 (7 M1R+/+ and 8 M1R−/−). In the current experiment, no pretraining procedures were used; therefore, two weeks after PAL task completion, mice were tested on a visual discrimination task with photographic stimuli.

2.4.2. Apparatus

The touchscreen system and mask specifications were identical to those previously described in experiment 2 (see ‘Apparatus’ section 2.2.2.).

2.4.3. Visual Discrimination with photographic stimuli

The procedures were identical to the visual discrimination task with shape stimuli (experiment 1). The pair of photographic stimuli that was used was face and building (see Figure 1C), which Bussey and colleagues (2008) and Winters and colleagues (2010) have shown can be discriminated by rats. Mice were first tested on the initial discrimination (S+: face and S−: building) for 20 sessions, and then the reversal discrimination (S+: building and S−: face) was tested for 20 sessions.

2.4.4. Data Analysis

Group means of accuracy (percent correct) were submitted to a two-way ANOVA where the first factor was the between-subjects factor of group and the second factor was the within-subjects factor of session for the initial visual discrimination and the reversal. All statistical analyses were conducted with a significance level of p = 0.05.

2.5. Experiment 5: Visual discrimination with morphed photographic stimuli

Since both groups (M1R+/+ and M1R−/−) performed at the same rate using photographic stimuli for a visual discrimination/reversal task (experiment 4), a more difficult stimulus pair was introduced in experiment 5.

2.5.1. Subjects

Cohort 2 mice were tested in experiment 5 (7 M1R+/+ and 8 M1R−/−).

2.5.2. Apparatus

The touchscreen system and mask specifications were identical to those previously described in (see experiment 2, ‘Apparatus’ section 2.2.2.).

2.5.3. Visual Discrimination with morphed photographic stimuli

The building and face stimuli were morphed together to contain more perceptual similarities with one another. The visual discrimination containing the morphed photographic stimuli (S+: building morph, S−: face morph) (see Figure 1D) was carried out for 10 sessions.

2.5.4. Data Analysis

Group means of accuracy (percent correct) were submitted to a two-way ANOVA where the first factor was the between-subjects factor of group and the second factor was the within-subjects factor of session acquisition of the visual discrimination. All statistical analyses were conducted with a significance level of p = 0.05.

2.6 Experiment 6: Spontaneous Object Recognition

2.6.1 Subjects

Cohort 3 contained 6 M1R+/+ and 5 M1R−/− male mice that were aged 12 to 16 weeks at the start of behavioral testing. Cohort 3 was obtained, housed, and fed in a similar manner to cohorts 1 and 2.

2.6.2 Apparatus

Spontaneous object recognition was conducted in a Y-shaped apparatus (Forwood et al. 2005; Bartko et al. 2007), adapted for mice. The apparatus had high, homogeneous white walls constructed from Perspex (Lucite International, Southampton, UK) to prevent the mouse from looking out into the room and thereby maximizing attention to the test stimuli. All walls were 30.5 high and each arm was 15 cm in length and 7 cm wide. The start arm contained a guillotine door 11 cm from the rear of the arm. This provided a start box area within which the mouse could be confined at the start of a given trial. Within each arm of the Y-apparatus were two sliding doors. The first sliding door was located 5 cm from the start box guillotine door (located at 11 cm from the rear of the start box) and the second sliding door was located 12 cm from the first sliding door. Each sliding door was 6.8 cm wide and 30.5 cm high, attached to the bottom of the sliding door was a platform where the stimuli could be placed. The floor and walls were wiped down with a dry paper towel between trials but otherwise were not cleaned during the experiment. A lamp illuminated the apparatus and a white shelf 30 cm from the top of the apparatus created a ceiling on which a video camera was mounted to record trials. Triplicate copies were obtained for the objects, which were made of plastic, glass, or metal. The height of the objects ranged from 3–10 cm, and the objects were secured to the platform of the doors (for sample objects) and to the apparatus (for choice objects) with Blu-Tack (Bostik, Stafford, UK). As far as could be determined, the objects had no natural significance for the mice, and they had never been associated with a reinforcer.

2.6.3 General Procedure

All mice were habituated during two consecutive daily sessions in which they were allowed to explore the empty Y-apparatus for 10 min. For these habituation sessions, the mouse was placed in the start box, and the guillotine door was opened to allow the rat to explore the main area of the apparatus. The guillotine door was lowered when the mouse exited the start box to prevent re-entry into this area of the apparatus. The experimenter did not begin timing the trial until the mouse exited the start box. Testing began 24 h after the second habituation session. Mice were given a series of 4 test trials (one per day) for each delay condition (minimal and 3 h) with a minimum interval of 24 h between trials. A different object pair was used for each trial for a given animal, and the order of exposure to object pairs as well as the designated sample and novel objects for each pair were counterbalanced within and across groups. The time spent exploring objects was assessed from video recordings of the sample and choice phases. Data were collected by scoring exploratory bouts using a personal computer running a program written in Visual Basic 6.0 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Object recognition test

Mouse object recognition testing proceeded very similarly to rat object recognition testing previously described (Bartko et al. 2007). The sample phase ended when 10 min had passed. At the end of the sample phase, the mouse was removed from the Y-shaped apparatus for the duration of the 3 h retention delay. For the choice phase, the mouse was allowed to explore the objects for 2 min, at the end of which the mouse was removed and returned to its home cage. The time spent exploring the novel and familiar objects was recorded for all 2 min of the choice phase, but attention was focused on the first minute, during which object discrimination is typically greatest. We calculated a discrimination ratio, the proportion of total exploration time spent exploring the novel object (i.e., the difference in time spent exploring the novel and familiar objects divided by the total time spent exploring the objects), for the first minute of the choice phase on each object recognition trial. This measure takes into account individual differences in the total amount of exploration time.

It was found that M1R−/− mice were impaired at a delay of three hours. We therefore carried out a subsequent experiment using a minimal delay to test whether the impairment was delay-dependent, or whether the KO affects other factors, for example novelty detection per se. The minimal delay condition was carried out in the same way as the 3-hour condition, with the exception that the mouse remained in the apparatus for the entire testing session (this procedure has been described previously in Bartko et al. 2007).

Data Analysis

Group means of three measures taken from object recognition testing [duration of sample phase (i.e., the time taken to accumulate criterion levels of exploration in the sample phase), total exploration time in the choice phase, and the discrimination ratio] were analyzed. Means from each of the three measures were analyzed with independent sample t tests. All tests of significance were performed at α= 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1: 5-CSRTT

3.1.2. Manipulation of 5-CSRTT task parameters: variable stimulus duration

3.1.2.1. Accuracy

When the stimulus duration was reduced to 0.8 s, accuracy levels were significantly reduced in both genotypes. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures conducted on the stimulus duration (2.0 s, 1.5 s, and 0.8 s) revealed no significant effect of genotype (F < 1) and no significant interaction of stimulus duration by genotype (F < 1). There was a significant main effect of stimulus duration (F(2,26) = 10.87, p = 0.001) (see accuracy graph, Figure 2A).

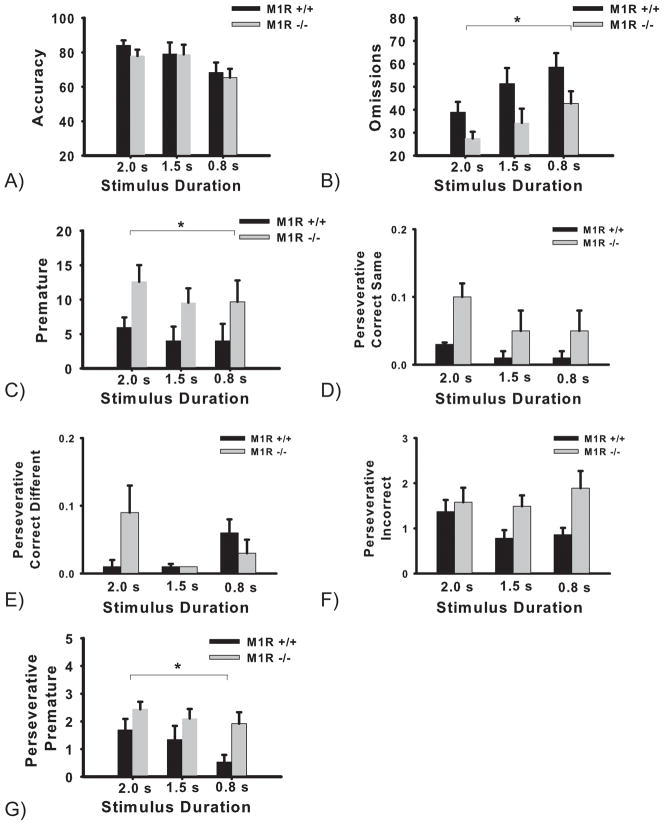

Figure 2.

Performance in the 5-CSRTT by M1R+/+ and M1R−/− mouse groups in the stimulus duration task challenge (2.0 s, 1.5 s, and 0.8 s). Accuracy, Omissions, and Premature graphs are presented as group mean percentages ± SEM (Omissions: * p = 0.02; Premature: * p = 0.05). Perseverative graphs (Correct Same, Correct Different, Incorrect, and Premature) are presented as group mean number of responses ± SEM (Perseverative Premature: * p = 0.03).

3.1.2.2. Omissions

By decreasing the stimulus duration, omissions significantly increased in both groups of mice. Analysis of the mean percentage of omissions revealed a significant effect of genotype (F(1,13) = 6.32, p = 0.02) and stimulus duration (F(2,26) = 12.26, p < 0.0001) (see omissions graph, Figure 2B). However, the interaction of stimulus duration by genotype was not significant (F < 1, p > 0.05).

3.1.2.3. Premature responses

Overall, the M1R−/− mice committed a significantly greater number of premature responses compared with the M1R+/+ group. Analysis of group mean premature responding following a reduction in stimulus duration revealed no significant effect of stimulus duration (F(2,26) = 1.79, p = 0.18), and the interaction of stimulus duration by genotype was also not significant (F(2,26) = 0.92, p > 0.05) (see premature graph, Figure 2C). However, analysis revealed a significant main effect of genotype (F(1,13) = 4.30, p = 0.05).

3.1.2.4. Perseverative responses

Overall, the M1R−/− mice committed a greater number (or a trend towards a greater number) of perseverative responses than the M1R+/+ group. Analysis of the mean number of perseverative correct same responses following reductions in stimulus duration revealed no significant effect of stimulus duration (F(2,26) = 2.70, p = 0.08), and no significant interaction of stimulus duration by genotype (F < 1), however there was a strong trend toward main effect of genotype (F(1,13) = 4.24, p = 0.06), (see perseverative correct same graph, Figure 2D). Furthermore, analysis of the mean number of perseverative correct different responses following reductions in stimulus duration revealed no significant effect of stimulus duration (F(2,26) = 2.57, p = 0.09), genotype (F < 1), and no significant interaction of stimulus duration by genotype (F(2,26) = 3.08, p = 0.06) (see perseverative correct different graph, Figure 2E). Analysis of perseverative incorrect responding revealed no significant effect of stimulus duration (F(2,26) = 1.59) or interaction of stimulus duration by genotype (F(2,26)= 2.2, p = 0.13), but a trend toward a main effect of genotype (F(1,13) = 3.78, p = 0.07). (see perseverative incorrect graph, Figure 2F).

The number of perseverative premature responses was analyzed and a two-way ANOVA revealed no significant interaction of stimulus duration by genotype (F < 1). However, analysis revealed a significant effect of stimulus duration (F(2,26) = 5.32, p = 0.01) and a significant effect of genotype (F(1,13) = 5.70, p = 0.03) (see perseverative premature graph, Figure 2G).

3.1.2.5. Reaction time

Reaction time for correct trials was not significantly different between M1R+/+ and M1R−/− mouse groups. Analysis of group mean reaction time revealed no significant effect of stimulus duration (F(2,26) = 1.45, p > 0.05), genotype (F < 1), and no interaction of stimulus duration by genotype (F < 1). The mean reaction times ± SEM for M1R+/+ and M1R−/− mouse groups for baseline sessions was as follows: M1R+/+: 2.0 s = 1.45 ± 0.18 s, 1.5 s = 1.32 ± 0.24 s; 0.8 s = 1.28 ± 0.20 s and M1R−/−: 2.0 s = 1.31 ± 0.26 s, 1.5 s = 1.26 ± 0.25 s; 0.8 s = 1.30 ± 0.37 s.

3.1.2.6. Magazine Latency

Magazine latency was not significantly different between M1R+/+ and M1R−/− mouse groups. Analysis of group mean reaction time revealed no significant effect of stimulus duration (F(2,26) = 1.42, p > 0.05), genotype (F < 1), and no interaction of stimulus duration by genotype (F < 1). The mean magazine latency ± SEM for M1R+/+ and M1R−/− mouse groups for baseline sessions was as follows: M1R+/+: 2.0 s = 1.81 ± 0.28 s, 1.5 s = 2.20 ± 0.64 s; 0.8 s = 1.96 ± 0.46 s and M1R−/−: 2.0 s = 2.92 ± 2.38 s, 1.5 s = 2.93 ± 2.39 s; 0.8 s = 2.92 ± 2.30 s.

3.1.3. Manipulation of 5-CSRTT parameters: 200 trial sessions

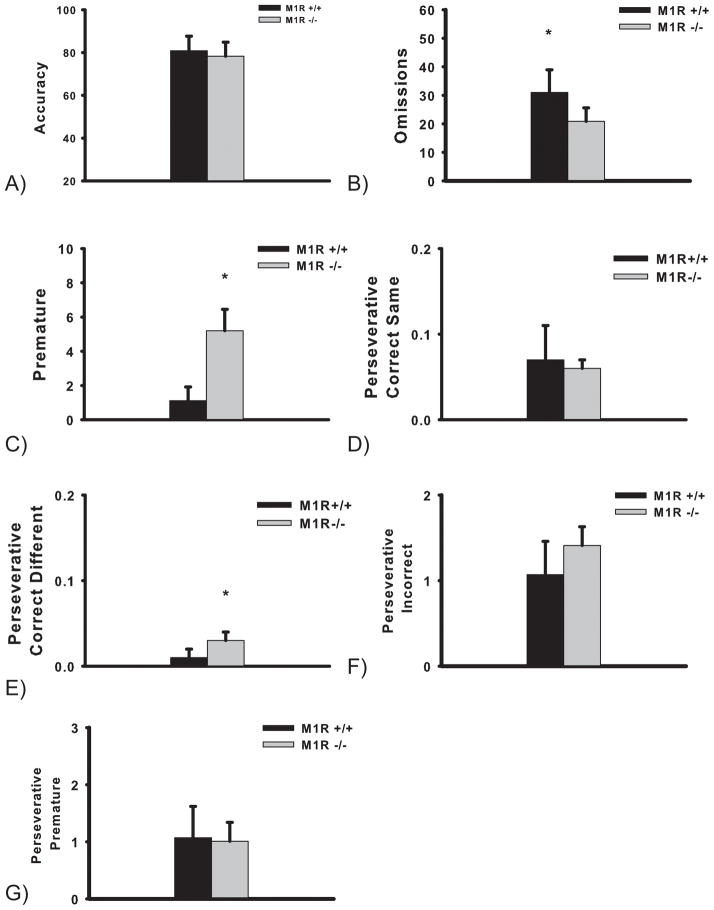

3.1.3.1. Accuracy

Accuracy levels were not different between M1R+/+ and M1R−/− mouse groups. Independent samples t-tests revealed no effect of genotype (t(13) = 2.10, p > 0.05) (see accuracy graph, Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Performance in the 5-CSRTT by M1R+/+ and M1R−/− mouse groups in the rapid event rate task challenge. Data are presented as group means of the first two bins (bin 1: trials 1–25; bin 2: trials 26–50) ± SEM (Omissions: * p = 0.02; Premature: * p = 0.002). Perseverative measures (Correct Same, Correct Different, Incorrect, and Premature) are the group mean number of perseverative responses ± SEM (Perseverative Correct Different * p < 0.05).

3.1.3.2. Omissions

The M1R+/+ group committed significantly more omissions that the M1R−/− group (t(13) = 2.64, p = 0.02) (see omissions graph, Figure 3B).

3.1.3.3. Premature

The M1R−/− group committed significantly more premature responses than the M1R+/+ group (t(13) = 3.92, p = 0.002) (see premature graph, Figure 3C).

3.1.3.4. Perseverative responses

The M1R−/− group committed significantly more perseverative correct different responses than the M1R+/+ group. Analysis of the mean number of perseverative correct same responses revealed no significant effect of genotype (t(13) = 0.17) (see perseverative correct same graph, Figure 3D). However, analysis of the mean group number of perseverative correct different responses revealed a significant effect of genotype (t(13) = 2.15, p < 0.05) (see perseverative correct different graph, Figure 3E). Analysis of perseverative incorrect responding revealed no significant difference in perseverative incorrect responding between genotypes (t(13) = 0.90, p > 0.05) (see perseverative incorrect graph, Figure 3F). Furthermore, analysis revealed no significant difference between genotypes in regard to perseverative premature responding (t(13) = 0.10, p > 0.05) (see perseverative premature graph, Figure 3G).

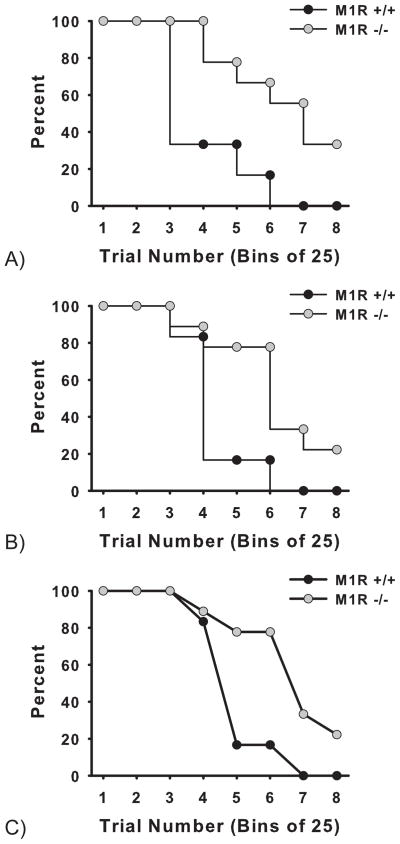

3.1.4 Survival analysis

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed a significant effect of genotype for each of the three days tested in the second task challenge: Day 1, (x 2 = 14.25, df = 1, p < 0.001); Day 2, (x 2 = 12.44, df = 1, p < 0.001), Day 3, (x 2 = 10.98, df = 1, p = 0.001) (see Figure 4). The analysis indicates a striking ability of the M1R−/− group to persevere in completing trials during all 3 of the extended test sessions.

Figure 4.

Survival analysis of the three days in the second task challenge of 5-CSRTT (2 s ITI, 2 sec stimulus duration, and 200 trials or 2 hr per session) revealed a significant effect of genotype, indicating that the M1R−/− group completed more trials than the M1R+/+ group.

3.2. Experiment 2: Visual Discrimination

3.2.1. Acquisition

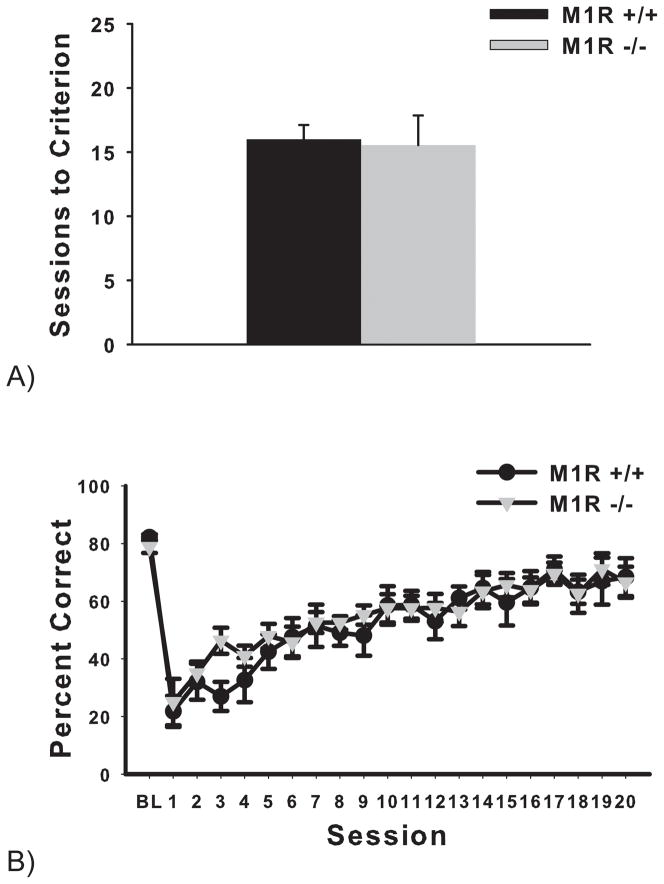

Acquisition of a simple visual discrimination was not impaired in the M1 receptor-deficient mice. Analysis of the group averages of sessions to criterion of the initial visual discrimination (S+: marbles, S−: fan) revealed no significant effect of genotype on performance (t(1,14) = 0.15, p > 0.05) (see Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

A) The M1R+/+ and M1R−/− groups did not acquire the visual discrimination touchscreen task using shape stimuli at a significantly different rate (experiment 1). Data are presented as group mean sessions to criterion ± SEM. B) The M1R+/+ and M1R−/− groups did not perform differently from one another in the reversal task (experiment 1). The five baseline sessions are averaged together as BL, followed by 20 sessions of the reversal discrimination. Data are presented as group mean percent correct ± SEM.

3.2.2. Reversal

Following a reversal of task contingencies (the S+ and the S− acquired in the initial discrimination were reversed), the M1 receptor-deficient group and wild-type group did not perform significantly differently from one another (see Figure 5B). A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures conducted on sessions revealed no significant effect of genotype (F < 1) and no significant interaction of session by genotype (F < 1). There was a significant main effect of session (F(19,266) = 20.19, p < 0.00001).

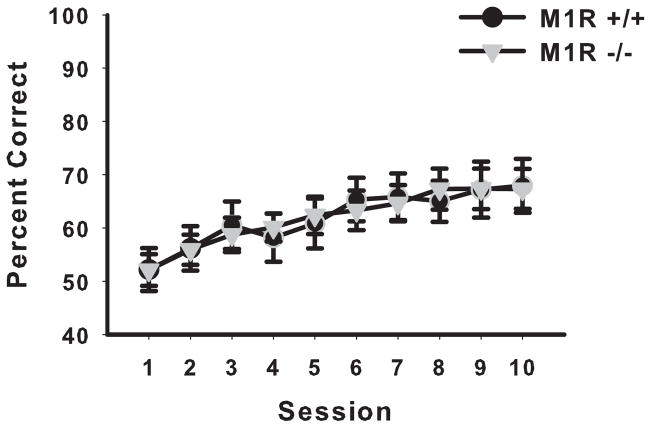

3.3. Experiment 3: Paired-Associates Learning

3.3.1. Acquisition

The M1R−/− group did not acquire the PAL task significantly differently from the M1R+/+ group (see Figure 6). A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures conducted on session revealed no significant effect of genotype (F < 1) and no significant interaction of session by genotype (F < 1). However, there was a significant main effect of session (F(49, 637) = 5.35, p < 0.00001).

Figure 6.

PAL task acquisition (illustration of the 50 sessions presented in 10 blocks of 5 sessions). The M1R+/+ and M1R−/− groups did not differentially acquire the PAL touchscreen task (experiment 2). Data are presented as mean group percent correct ± SEM.

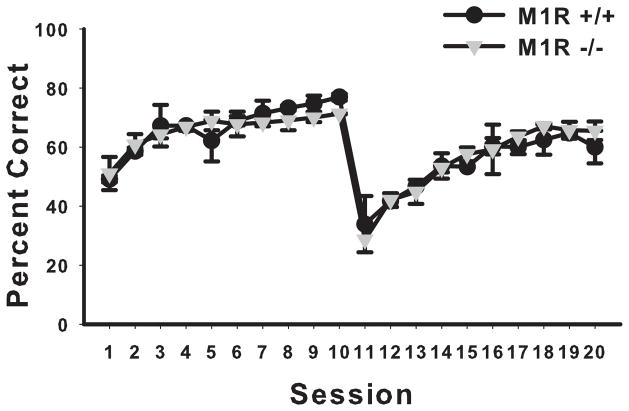

3.4. Experiment 4: Visual discrimination task with photographic stimuli

3.4.1. Acquisition

The M1R−/− group and the M1R+/+ group did not perform significantly differently from one another in acquiring the initial discrimination with photographic stimuli (S+: face and S−: building) (see Figure 7). A two-way ANOVA with session as the repeated measures factor revealed no significant effect of genotype (F < 1) and no significant interaction of session by genotype (F < 1). There was a significant main effect of session (F(19,247) = 7.25, p < 0.00001).

Figure 7.

The M1R+/+ and M1R−/− groups did not perform differently from one another in the acquisition or the reversal of the discrimination task using photographic stimuli (experiment 3) (data are presented in blocks of 2 sessions). Sessions are presented in blocks of two. Sessions 1–10 are the acquired discrimination (S+ (face) and S− (building)) and sessions 11–20 are the reversal discrimination (S+ (building) and S− (face)). Data are presented as mean group percent correct ± SEM.

3.4.2. Reversal

The M1R−/− group and the M1R+/+ group also did not perform significantly differently from one another in acquiring the reversal discrimination (S+: building and S−: face) (see Figure 7). A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures conducted on sessions revealed no significant effect of genotype (F < 1) and no significant interaction of session by genotype (F < 1). There was a significant main effect of session (F(19,247) = 18.75, p < 0.00001).

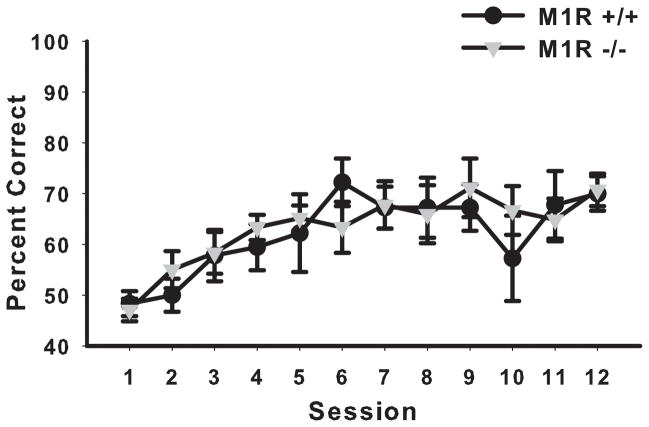

3.5. Experiment 5: Visual discrimination with morphed photographic stimuli

Since both groups (M1R+/+ and M1R−/−) performed at the same rate using photographic stimuli for a visual discrimination/reversal task (experiment 4), a more difficult stimulus pair was introduced in experiment 5.

3.5.1. Acquisition

Morphing the stimuli together greatly decreased performance of the discrimination; both groups dropped to chance levels. Mice were allowed to acquire the new discrimination across 12 sessions. The M1R−/− group and the M1R+/+ group did not perform significantly different from one another in acquiring this new discrimination (see Figure 8). A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures conducted on sessions revealed no significant effect of genotype (F < 1) and no significant interaction of session by genotype (F < 1). There was a significant main effect of session (F(11,143) = 6.67, p < 0.00001).

Figure 8.

The M1R+/+ and M1R−/− groups did not perform differently from one another in the acquisition of the visual discrimination task (experiment 4) using morphed photographic stimuli. Data are presented as mean group percent correct ± SEM.

3.6 Experiment 6: Spontaneous object recognition

Object recognition memory was first examined using a 3 h delay between the sample and choice phase to determine whether M1R−/− mice have impaired memory for objects across a delay. Indeed, M1R−/− mice were impaired at a delay of three hours (see below). We therefore carried out a subsequent experiment using a minimal delay between the sample and choice phases to determine whether the impairment was delay-dependent or whether deletion of the M1 receptor in knockout mice affected other factors, for example, novelty detection per se.

3.6.1 Three-hour delay

3.6.1.1 Object exploration during sample phase

All mice were exposed to the sample objects for 10 mins. The total exploration in the sample phase was analyzed with independent samples t-tests since significant genotype differences at this stage of a trial might lead to differences in subsequent recognition performance. Independent samples t-tests revealed no significant effect (t(9) = 0.14). The mean sample phase exploration (±SEM) for the two genotypes was as follows: M1R−/−, 66.52 ± 17.17 s, M1R+/+, 65.28 ± 10.96 s.

3.6.1.2 Object exploration during choice phase

Analysis of the total mean object exploration time during the choice phase revealed no significant effect (t(9) = 0.31). The mean choice phase exploration (±SEM) for genotypes was as follows: 3 h delay: M1R−/−, 5.99 ± 2.47s and M1R+/+, 8.81 ± 3.56 s.

3.6.1.3 Recognition during the choice phase

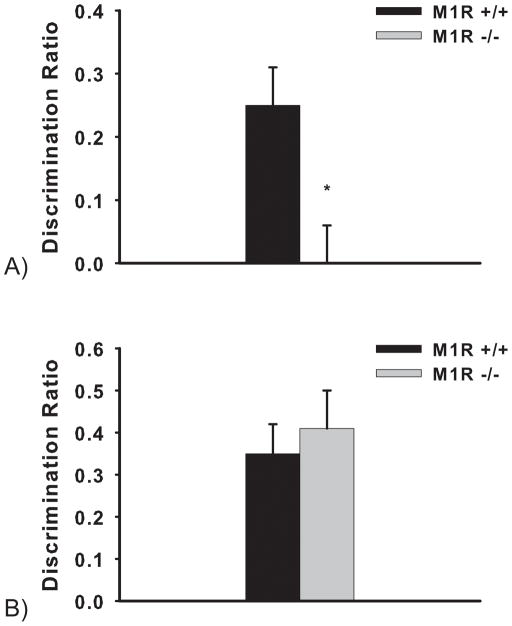

The M1R−/− mice performed significantly worse than the M1R−/− mice; independent samples t-tests revealed a significant effect of genotype (t(9)= 3.13; p = 0.01; see Figure 9A).

Figure 9.

Performance on object recognition with a 3 h (A) and minimal (B) delay in M1R+/+ and M1R−/− groups. Data are presented as average discrimination ratio ± SEM. *p=0.01

3.6.2 Minimal delay

3.6.2.1 Object exploration during sample phase

Again there was no difference in the amount of sample exploration between the M1R−/− and M1R+/+ mice; independent samples t-test revealed t(9) = 0.14. The mean sample phase exploration (±SEM) for the two genotypes was as follows: M1R−/−, 74.21 ± 15.24 s and M1R+/+, 79.35 ± 9.40 s.

3.6.2.2 Object exploration during choice phase

Analysis of the total mean object exploration during the choice phase revealed no significant effect (t(9) =1.49). The mean choice phase exploration (±SEM) for genotypes was as follows: M1R−/−, 13.56 ± 1.23 s, M1R+/+, 13.30 ± 1.54 s.

3.6.2.3 Recognition during the choice phase

Although the M1R−/− were impaired in the 3-hour delay experiment, when the choice objects were revealed to the mice immediately in the minimal delay experiment, the M1R−/− mice and the M1R+/+ mice did not differ: both genotypes could discriminate the novel from the familiar stimulus in the choice phase (t(9) = 0.54; see Figure 9B).

4. Discussion

The present study sought to clarify the role of M1 receptors in cognition by examining the performance of M1R−/− mice on the 5-CSRTT of attentional and response functions, in addition to several tasks featuring learning, memory and perceptual challenges. A major, surprising finding, given the predominance of the M1 receptor in cortex, was the complete lack of effect of M1 deletion on measures of attentional function per se. Specifically, M1R−/− mice showed not greater, but fewer omissions (misses), providing no evidence of a difficulty in detecting the briefly presented targets. Furthermore, once the target was detected, choice accuracy was also normal. This lack of effect cannot be due to insensitivity of the task, as the task run in the same manner has been shown to detect attentional impairments, for example in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (Romberg et al., 2011). Moreover, M1R−/− mice displayed normal learning of a two-choice visual discrimination, and showed normal inhibition of a previously learned association when the reward contingencies were reversed, even under conditions of high perceptual demand. A difficult test of object-in-place memory, PAL, was also acquired normally by mice lacking M1 muscarinic receptors. However M1R−/− mice were impaired on an object recognition task at a 3 hour delay, but not when the delay was very short, indicating that M1 receptor deletion can impair memory across a delay, but leaves novelty detection per se intact.

The finding that M1R−/− mice did not demonstrate impairments in several cognitive domains is striking given that the mouse is a global knock-out. In contrast to these preserved learning, memory, and perceptual functions, M1R−/− mice displayed clear abnormalities in the 5-CSRTT. Specifically, M1R−/− mice made fewer omissions, more premature responses, and more perseverative responses. Increased perseverative responding of the M1R−/− mice in the 5-CSRTT contrasts with normal perseveration on two tests of reversal learning and suggests a dissociation between response perseveration and “stimulus-bound” perseveration (Ridley, 1994; Ridley et al., 1993; Sandson and Albert, 1984). Perhaps the most striking finding, however, was the ability of the M1R−/− mice to persevere in completing trials: survival analysis of data from the high event rate challenge showed that M1R−/− mice were able to complete significantly more trials than wild-type mice, a finding that was replicated on each of the three days of testing in the 200 trials/session condition.

Manipulations of the cholinergic system such as administration of scopolamine, basal forebrain lesions, and cholinergic denervation of the prefrontal cortex have also been shown to lead to deficits in attentional accuracy (e.g., decreased accuracy and increased omissions) in the 5-CSRTT (Dalley et al., 2004; Lehmann et al., 2003; McGaughy et al., 2002; Mirza and Stolerman, 2000; Muir et al., 1995; Passetti et al., 2000; Pattij et al., 2007); however it has not been established through which cholinergic receptor subtypes these effects are mediated. The findings of the present study indicate that the impairments in accuracy and increases in omission following such manipulations may not be due to a lack of cholinergic activity at M1 muscarinic receptors, and suggest that other cholinergic receptors mediate accurate attentional selection in this task. Preliminary results suggest that M2 receptors are involved in attention, as M2 receptor-deficient mice demonstrate improved accuracy in the 5-CSRTT (C. Romberg, T.J. Bussey, and L.M Saksida, unpublished observations), consistent with the proposal that M2 receptors function as presynaptic autoreceptors, the deletion of which could lead to increased acetylcholine levels and improved attention.

An alternative explanation for the apparently preserved attentional function in M1R−/− mice, suggested by an anonymous reviewer, is that performance may depend more on cholinergic modulation if the task is learned in the presence of an intact cholinergic system. Studies using the 5-CSRTT typically examine the effects of drugs or other manipulations on performance of the task after the baseline task conditions have been acquired. Such a hypothesis would be consistent with the intact performance of the M1R−/− mice on the PAL task, which is impaired by the M1-preferring antagonists dicyclomine after the task has been acquired by normal wild-type mice (Bartko et al., 2011). This is unlikely to be a general rule, however; for example Voytko et al. (1994) showed that monkeys that learned an attentional task in the presence of basal forebrain lesions were still impaired performing the task post-acquisition (and were relatively unimpaired on other tests of learning and memory). It is also possible that compensatory processes in this constitutive knock-out may have contributed to the preserved cognitive function observed in M1R−/− mice in the present study; however, if compensatory changes do occur they are not sufficient to rescue the abnormal responding and object recognition impairment seen in these animals. Furthermore, it seems unlikely that such compensatory changes include changes in the expression of other muscarinic receptors, as several studies have indicated that M1 receptor deletion does not lead to changes in expression of M2–M5 receptors in the striatum or hippocampus (Hamilton et al., 1997; Miyakawa et al. 2001; Fisahn et al. 2002; Dasari and Gulledge, 2011). However it is conceivable that compensatory changes may have occurred in other structures and/or other neurotransmitter systems leading to rescue of some cognitive functions, but not others.

The finding that M1R−/− mice display abnormal responding in the face of substantial preserved learning is concordant with other studies. Miyakawa et al (2001), for example, report mostly intact learning and memory in M1R−/− mice, but increased hyperactivity, a pattern consistent with that found here. This hyperactivity phenotype in M1R−/− mice has been attributed to increased dopamine (DA) levels in the striatum (Gerber et al., 2001; Woolley et al., 2009). As DA depletion in the striatum alters indices of response vigor but not accuracy in the 5-CSRTT (Baunez and Robbins, 1999; Cole and Robbins, 1989) it seems likely that at least some of the abnormal responding in the 5-CSRTT observed in the present study may be due to mechanisms involving striatal DA. Alterations in striatal DA suggest a possible link between M1 receptor function and schizophrenia. Indeed, psychotomimetic treatments such as phencyclidine (PCP) can reproduce abnormal responding on the 5-CSRTT, such as increased premature and perseverative responding (Amitai et al., 2007; Greco et al., 2005; Le Pen et al., 2003), similar to that observed in the M1R−/− mice in the present study, and many authors have suggested a link between M1 receptors and schizophrenia in humans (Conn et al., 2009; Scarr and Dean, 2009; Sellin et al., 2008).

As described above, our study and others (Miyakawa et al. 2001; Gerber et al., 2001) indicate that M1R−/− mice display abnormal responding (e.g., hyperactivity and/or perseveration) in the face of substantial preserved learning. However, whereas we found spared performance in several touchscreen tests involving learning and memory, Anagnostaras and colleagues (2003) have reported impaired, normal, and even enhanced performance in several different hippocampal-dependent learning and memory tasks. Wess (2004) has suggested that changes in locomotor activity could conceivably contribute to performance alterations in these tasks. Since most of the tasks in the present study were carried out in the touchscreen apparatus and thus used the same types of stimuli, responses, rewards and other feedback, and were carried out in the same testing environment, the possibility of nonspecific confounding factors (e.g. changes in locomotor function) was minimized. In one task, however -- object recognition -- we found that M1R−/− mice were impaired at a 3 hour delay, but not when the delay was short, indicating that M1 receptor deletion can impair memory across a delay, but leaves novelty detection per se intact. That the M1R−/− mice were not impaired at short delays also indicates that the impairment at 3 hours was not due to gross motor or perceptual changes, or the ability of M1R−/− mice to respond appropriately to novel objects under conditions of low memory load. Indeed there was no difference in the overall amount of exploration of objects by the M1 R−/− mice, either during the sample or during the choice phase. This finding is thus consistent with the memory impairments reported by Anagnostaras et al. (2003). Indeed, one point of commonality between the studies of Miyakawa et al. (2001) and Anagnostaras et al. (2003) was the reported impairment in some forms of memory. Furthermore the finding that attentional function is preserved in M1R−/− mice, at least as measured by the 5-CSRTT, suggests that these apparent memory impairments were not secondary to an attentional impairment leading to impoverished sample encoding. It is worth noting that the dependence of M1 receptors on object recognition has also recently been shown using the M1 receptor antagonists pirenzepine or MT-7 infused directly into perirhinal cortex (Bartko et al., 2008).

The clear lack of impairment in M1R−/− mice on several tasks and measures in the touchscreen battery cannot be due to task insensitivity. Discrimination learning in the touchscreen has been shown to be impaired by, for example, inactivation of perirhinal cortex (Winters et al., 2010), NR2A receptor subunit knock-out in the mouse (Brigman et al., 2008), and in aged R6/2 (Huntington’s) mice (Morton et al., 2006). Reversal learning in the touchscreen is impaired by prefrontal cortex lesions in the rat (Bussey et al., 1997; Chudasama et al., 2003), and in R6/2 mice (Morton et al., 2006). PAL performance is impaired by lidocaine and blockade of NMDA and AMPA receptors in the hippocampus (Talpos et al., 2009). The present study thus demonstrates a number of tasks for which M1 receptors are not necessary, including target detection ability as measured by the 5-CSRTT. These findings and others do, however, implicate these receptors in normal responding, certain perceptual discriminations and certain types of memory.

Highlights.

We examined the functional role of the M1 receptor in cognition

We report abnormal responding of M1 knockout mice in the touchscreen 5-CSRTT

M1R−/− mice were unimpaired in touchscreen learning, memory, and perception tasks

M1R−/− mice were impaired at object recognition memory with a delay

M1R is involved in distinct aspects of cognition

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Project Grant and an Alzheimer’s Research Trust grant to T.J.B. and L.M.S. S.J.B. was additionally supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein Predoctoral Fellowship from the National Institutes of Mental Health.

References

- Amitai N, Semenova S, Markou A. Cognitive-disruptive effects of the psychotomimetic phencyclidine and attenuation by atypical antipsychotic medications in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193:521–537. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0808-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostaras SG, Murphy GG, Hamilton SE, Mitchell SL, Rahnama NP, Nathanson NM, Silva AJ. Selective cognitive dysfunction in acetylcholine M1 muscarinic receptor mutant mice. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:51–58. doi: 10.1038/nn992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartko SJ, Vendrell I, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ. A computer-automated touchscreen paired-associates learning (PAL) task for mice: impairments following administration of scopolamine or dicyclomine and improvements following donepezil. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214:537–548. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartko SJ, Winters BD, Cowell RA, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ. Perceptual functions of perirhinal cortex in rats: zero-delay object recognition and simultaneous oddity discriminations. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2548–59. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5171-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartko SJ, Winters BD, Wess J, Mattson MP, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ. The role of cholinergic muscarinic receptor subtypes in spontaneous object recognition and simultaneous oddity discrimination tasks. Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; Washington, D.C. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bartus RT, Dean RL, 3rd, Beer B, Lippa AS. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science. 1982;217:408–414. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baunez C, Robbins TW. Effects of dopamine depletion of the dorsal striatum and further interaction with subthalamic nucleus lesions in an attentional task in the rat. Neuroscience. 1999;92:1343–1356. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigman JL, Feyder M, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, Mishina M, Holmes A. Impaired discrimination learning in mice lacking the NMDA receptor NR2A subunit. Learn Mem. 2008;15:50–54. doi: 10.1101/lm.777308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Muir JL, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Triple dissociation of anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate, and medial frontal cortices on visual discrimination tasks using a touchscreen testing procedure for the rat. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:920–936. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.5.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Padain TL, Skillings EA, Winters BD, Morton AJ, Saksida LM. The touchscreen cognitive testing method for rodents: how to get the best out of your rat. Learn Mem. 2008;15:516–523. doi: 10.1101/lm.987808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Saksida LM, Rothblat LA. Discrimination of computer-graphic stimuli by mice: a method for the behavioral characterization of transgenic and gene-knockout models. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:957–960. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.4.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bymaster FP, Felder C, Ahmed S, McKinzie D. Muscarinic receptors as a target for drugs treating schizophrenia. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2002;1:163–181. doi: 10.2174/1568007024606249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carli M, Robbins TW, Evenden JL, Everitt BJ. Effects of lesions to ascending noradrenergic neurones on performance of a 5-choice serial reaction task in rats; implications for theories of dorsal noradrenergic bundle function based on selective attention and arousal. Behav Brain Res. 1983;9:361–380. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(83)90138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudasama Y, Dalley JW, Nathwani F, Bouger P, Robbins TW. Cholinergic modulation of visual attention and working memory: dissociable effects of basal forebrain 192-IgG-saporin lesions and intraprefrontal infusions of scopolamine. Learn Mem. 2004;11:78–86. doi: 10.1101/lm.70904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudasama Y, Passetti F, Rhodes SE, Lopian D, Desai A, Robbins TW. Dissociable aspects of performance on the 5-choice serial reaction time task following lesions of the dorsal anterior cingulate, infralimbic and orbitofrontal cortex in the rat: differential effects on selectivity, impulsivity and compulsivity. Behav Brain Res. 2003;146:105–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudasama Y, Robbins TW. Psychopharmacological approaches to modulating attention in the five-choice serial reaction time task: implications for schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:86–98. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1805-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole BJ, Robbins TW. Effects of 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the nucleus accumbens septi on performance of a 5-choice serial reaction time task in rats: implications for theories of selective attention and arousal. Behav Brain Res. 1989;33:165–179. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(89)80048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PJ, Jones CK, Lindsley CW. Subtype-selective allosteric modulators of muscarinic receptors for the treatment of CNS disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Price DL, DeLong MR. Alzheimer’s disease: a disorder of cortical cholinergic innervation. Science. 1983;219:1184–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.6338589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasari S, Gullege AT. M1 and M4 receptors modulate hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:779–92. doi: 10.1152/jn.00686.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Laane K, Theobald DE, Pena Y, Bruce CC, Huszar AC, Wojcieszek M, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Enduring deficits in sustained visual attention during withdrawal of intravenous methylenedioxymethamphetamine self-administration in rats: results from a comparative study with d-amphetamine and methamphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1195–1206. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, McGaughy J, O’Connell MT, Cardinal RN, Levita L, Robbins TW. Distinct changes in cortical acetylcholine and noradrenaline efflux during contingent and noncontingent performance of a visual attentional task. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4908–4914. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04908.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Theobald DE, Berry D, Milstein JA, Laane K, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Cognitive sequelae of intravenous amphetamine self-administration in rats: evidence for selective effects on attentional performance. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:525–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Theobald DE, Bouger P, Chudasama Y, Cardinal RN, Robbins TW. Cortical cholinergic function and deficits in visual attentional performance in rats following 192 IgG-saporin-induced lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:922–932. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean B, Bymaster FP, Scarr E. Muscarinic receptors in schizophrenia. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3:419–426. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglen RM, Choppin A, Dillon MP, Hegde S. Muscarinic receptor ligands and their therapeutic potential. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1999;3:426–432. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(99)80063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder CC, Bymaster FP, Ward J, DeLapp N. Therapeutic opportunities for muscarinic receptors in the central nervous system. J Med Chem. 2000;43:4333–4353. doi: 10.1021/jm990607u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisahn A, Yamada M, Duttaroy A, Gan JW, Deng CX, McBain CJ, Wess J. Muscarinic induction of hippocampal gamma oscillations requires coupling of the M1 receptor to two mixed cation currents. Neuron. 2002;33:615–624. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher A. M1 muscarinic agonists target major hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease--the pivotal role of brain M1 receptors. Neurodegener Dis. 2008;5:237–240. doi: 10.1159/000113712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forwood SE, Winters BD, Bussey TJ. Hippocampal lesions that abolish spatial maze performance spare object recognition memory delays of up to 48 hours. Hippocampus. 2005;15:347–55. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn DD, Ferrari-DiLeo G, Mash DC, Levey AI. Differential regulation of molecular subtypes of muscarinic receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1995;64:1888–1891. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64041888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JI. Cholinergic targets for cognitive enhancement in schizophrenia: focus on cholinesterase inhibitors and muscarinic agonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:45–53. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1794-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Delineating muscarinic receptor functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12222–12223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber DJ, Sotnikova TD, Gainetdinov RR, Huang SY, Caron MG, Tonegawa S. Hyperactivity, elevated dopaminergic transmission, and response to amphetamine in M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15312–15317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261583798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granon S, Passetti F, Thomas KL, Dalley JW, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Enhanced and impaired attentional performance after infusion of D1 dopaminergic receptor agents into rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1208–1215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01208.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco B, Invernizzi RW, Carli M. Phencyclidine-induced impairment in attention and response control depends on the background genotype of mice: reversal by the mGLU(2/3) receptor agonist LY379268. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179:68–76. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SE, Loose MD, Qi M, Levey AI, Hille B, McKnight GS, Idzerda RL, Nathanson NM. Disruption of the m1 receptor gene ablates muscarinic receptor-dependent M current regulation and seizure activity in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13311–13316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes FE, Mahoney SA, Wynick D. Use of genetically engineered transgenic mice to investigate the role of galanin in the peripheral nervous system after injury. Neuropeptides. 2005;39:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humby T, Laird FM, Davies W, Wilkinson LS. Visuospatial attentional functioning in mice: interactions between cholinergic manipulations and genotype. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:2813–2823. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DN, Higgins GA. Effect of scopolamine on visual attention in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120:142–149. doi: 10.1007/BF02246186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson RM, Tanaka K, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, Heilig M, Holmes A. Assessment of Glutamate Transporter GLAST (EAAT1)-Deficient Mice for Phenotypes Relevant to Negative and Executive/Cognitive Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;34:1578–1589. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead CJ, Watson J, Reavill C. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors as CNS drug targets. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;117:232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Pen G, Grottick AJ, Higgins GA, Moreau JL. Phencyclidine exacerbates attentional deficits in a neurodevelopmental rat model of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1799–1809. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann O, Grottick AJ, Cassel JC, Higgins GA. A double dissociation between serial reaction time and radial maze performance in rats subjected to 192 IgG-saporin lesions of the nucleus basalis and/or the septal region. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:651–666. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Kitt CA, Simonds WF, Price DL, Brann MR. Identification and localization of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor proteins in brain with subtype-specific antibodies. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:3218–3226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03218.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaughy J, Dalley JW, Morrison CH, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Selective behavioral and neurochemical effects of cholinergic lesions produced by intrabasalis infusions of 192 IgG-saporin on attentional performance in a five-choice serial reaction time task. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1905–1913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01905.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza NR, Stolerman IP. The role of nicotinic and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in attention. Psychopharmacology. 2000;148:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130050048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakawa T, Yamada M, Duttaroy A, Wess J. Hyperactivity and intact hippocampus-dependent learning in mice lacking the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5239–5250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05239.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton AJ, Skillings E, Bussey TJ, Saksida LM. Measuring cognitive deficits in disabled mice using an automated interactive touchscreen system. Nat Methods. 2006;3:767. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1006-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir JL, Dunnett SB, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Attentional functions of the forebrain cholinergic systems: effects of intraventricular hemicholinium, physostigmine, basal forebrain lesions and intracortical grafts on a multiple-choice serial reaction time task. Experimental Brain Research. 1992;89:611–622. doi: 10.1007/BF00229886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir JL, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Reversal of visual attentional dysfunction following lesions of the cholinergic basal forebrain by physostigmine and nicotine but not by the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, ondansetron. Psychopharmacology. 1995;118:82–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02245253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir JL, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. The cerebral cortex of the rat and visual attentional function: dissociable effects of mediofrontal, cingulate, anterior dorsolateral, and parietal cortex lesions on a five-choice serial reaction time task. Cerebral Cortex. 1996;6:470–481. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passetti F, Dalley JW, O’Connell MT, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Increased acetylcholine release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex during performance of a visual attentional task. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3051–3058. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattij T, Janssen MC, Loos M, Smit AB, Schoffelmeer AN, van Gaalen MM. Strain specificity and cholinergic modulation of visuospatial attention in three inbred mouse strains. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:579–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puumala T, Ruotsalainen S, Jakala P, Koivisto E, Riekkinen P, Jr, Sirvio J. Behavioral and pharmacological studies on the validation of a new animal model for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1996;66:198–211. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley RM. The psychology of perserverative and stereotyped behaviour. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;44:221–231. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley RM, Clark BA, Durnford LJ, Baker HF. Stimulus-bound perseveration after frontal ablations in marmosets. Neuroscience. 1993;52:595–604. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW. Arousal systems and attentional processes. Biol Psychol. 1997;45:57–71. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(96)05222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW. The 5-choice serial reaction time task: behavioural pharmacology and functional neurochemistry. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:362–380. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romberg C, Mattson MP, Mughal MR, Bussey TJ, Saksida LM. Impaired attention in the 3xTgAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: Rescure by Donepezil (Aricept) J Neurosci. 2011;31:3500–3507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5242-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandson J, Albert ML. Varieties of perseveration. Neuropsychologia. 1984;22:715–732. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(84)90098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, Bruno JP. Cortical cholinergic inputs mediating arousal, attentional processing and dreaming: differential afferent regulation of the basal forebrain by telencephalic and brainstem afferents. Neuroscience. 2000;95:933–952. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarr E, Dean B. Role of the cholinergic system in the pathology and treatment of schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:73–86. doi: 10.1586/14737175.9.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin AK, Shad M, Tamminga C. Muscarinic agonists for the treatment of cognition in schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2008;13:985–996. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900014048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talpos JC, Winters BD, Dias R, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ. A novel touchscreen-automated paired-associate learning (PAL) task sensitive to pharmacological manipulation of the hippocampus: a translational rodent model of cognitive impairments in neurodegenerative disease. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;205:157–68. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1526-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice: novel phenotypes and clinical implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:423–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J, Eglen RM, Gautam D. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: mutant mice provide new insights for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:721–733. doi: 10.1038/nrd2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]