Abstract

We investigated the effects of a multi-station proprioceptive exercise program on functional capacity, perceived knee pain, and sensoriomotor function. Twenty-two patients (aged 41-75 years) with grade 2-3 bilateral knee osteoarthrosis were randomly assigned to two groups: treatment (TR; n = 12) and non-treatment (NONTR; n = 10). TR performed 11 different balance/coordination and proprioception exercises, twice a week for 6 weeks. Functional capacity and perceived knee pain during rest and physical activity was measured. Also knee position sense, kinaesthesia, postural control, isometric and isokinetic knee strength (at 60, 120 and 180°·s-1) measures were taken at baseline and after 6 weeks of training. There was no significant difference in any of the tested variables between TR and NONTR before the intervention period. In TR perceived knee pain during daily activities and functional tests was lessened following the exercise program (p < 0.05). Perceived knee pain was also lower in TR vs. NONTR after training (p < 0.05). The time for rising from a chair, stair climbing and descending improved in TR (p < 0.05) and these values were faster compared with NONTR after training (p < 0.05). Joint position sense (degrees) for active and passive tests and for weight bearing tests improved in TR (p < 0.05) and the values were lower compared with NONTR after training (p < 0.05). Postural control (‘eyes closed’) also improved for single leg and tandem tests in TR (p < 0.01) and these values were higher compared with NONTR after training. The isometric quadriceps strength of TR improved (p < 0.05) but the values were not significantly different compared with NONTR after training. There was no change in isokinetic strength for TR and NONTR after the training period. The results suggest that using a multi-station proprioceptive exercise program it is possible to improve postural control, functional capacity and decrease perceived knee pain in patients with bilateral knee osteoarthrosis.

Key Points.

It is possible to improve postural control, functional capacity and decrease perceived knee pain in patients with bilateral knee osteoarthrosis with a pure proprioceptive/ balance exercise program used in the present study.

The exercise regime used in the present study was as effective as previous studies, but of much shorter duration and utilized unsophisticated, inexpensive equipment which is available in most physiotherapy departments.

Therefore, the incorporation of this exercise program into clinical practice is readily feasible.

Key Words: Osteoarthrosis, proprioception, balance, perceived knee pain, function

Introduction

Osteoartrhosis (OA) is a slowly evolving articular disease, which appears to originate in the cartilage and affects the underlying bone, soft tissues and synovial fluid (Badley and Tennant, 1992; Kirwan and Silman, 1987). This condition usually occurs late in life, principally affecting the hand, and large weight bearing joints such as the knee (Mankin, 1989). It is particularly disabling when the knees are affected since the ability to walk, to rise from a chair and to use stairs is limited. Since, 30-40% of the elderly population over the age of 60 years suffers from knee OA (Felson, 1990) the condition is likely to contribute to disability in this population.

Impaired proprioception has been reported for the patients suffering from knee osteoarthrosis (Barret et al., 1991; Hassan et al., 2001; Hurley et al., 1997). However, few investigations (Hurley et al., 1997; Marks, 1994a; Swanik et al., 2000) have investigated the relationship between impaired proprioception and performance or other measures of functional status in OA. The integrity and control of sensorimotor systems that is, proprioceptive acuity and muscle contraction are essential for the maintenance of balance and production of a smooth, stable gait (Fitzpatrick and McCloskey, 1994; Lord et al., 1996). If knee OA impairs quadriceps function this may also impair the patient’s balance and gait, reducing their mobility and function. In addition, quadriceps sensory dysfunction, i.e. decreased proprioceptive acuity, has recently been demonstrated in patients with knee OA and proposed as a factor in the pathogenesis or progression of the condition (Birmingham et al., 2001; Hurley et al., 1997; Koralewicz and Engh, 2000). If correct, restoration of these sensorimotor deficits with rehabilitation may retard progression of knee OA and reduce disability. Gait training, biofeedback, electric stimulation, and facilitation techniques primarily used in the rehabilitation of patients with neurologic impairments have been proposed as alterative approaches to enhance proprioception (Marks, 1994b). Although it is generally accepted that a rehabilitation program improves the functional capacity, pain and sensoriomotor function of patients (Rogind et al., 1998; Hurley, 2003; Hurley and Scott, 1998; Hurley et al., 1997, Kettunen and Kujala, 2004; Roddy et al., 2005), there is lack of agreement about what such a rehabilitation program should include (Bijlsma and Dekker, 2005; Hurley, 2003; Kettunen and Kujala, 2004; Roddy et al., 2005). In addition, many previous studies have generally used sophisticated and expensive apparatus, which limits their application to a community setting.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the effects of a 6 week multi-station proprioceptive exercise program on functional capacity, perceived knee pain, and sensoriomotor function in patients with bilateral knee osteoartrhosis.

Methods

Patients

Twenty-two patients with bilateral complaints of knee OA, who had grade 2 or 3 OA, as judged by criteria of the American College Rheumatology (Altman et al., 1986), based on weight-bearing radiographs were admitted to the study. None of the patients had any neurological disorder (e.g. Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s) and/or a vestibular disorder, previous surgery on either knee, or symptomatic disease of the hip, ankle, or foot. In addition, none of the volunteers had received intra-articular steroid or hyaluronic acid injections in the preceding 6 months, neither had they received physiotherapy treatment, nor had they any knee cruciate ligament injury. The patients were informed about testing procedures, possible risks and discomfort that might ensue and gave their written informed consent to participate in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (WMAD, 2000).

All subjects were employed in an office or were retired, spending most of the day sitting. The activity level for all subjects remained relatively constant during the experimental period. The patients were randomly assigned to two groups: treatment (TR; n = 12, [9 women and 3 men], age 59 ± 8.9 years; height 1.58 ± 0.09 m and body mass 81.6 ± 13.8 kg) and non-treatment (NONTR; n = 10, [7 women and 3 men], age 62 ± 8.1 years; height 1.58 ± 0.09 m and body mass 74.6 ± 8.8 kg).

Perceived knee pain

Pain was subjectively evaluated using a 0 -100 mm visual analog scale (VAS, 0 = no pain; 100 = unbearable pain), which assesses the severity of pain in general, at night, after inactivity, sitting, rising from a chair, standing, walking and stair climbing. They were also asked to rate the pain perceived in their knee immediately after the functional capacity tests.

Functional capacity measurements

Patients indicated a subjective scoring of an appropriate number on a 0 to 10 point Numerical Rating Scale (0 = minimal functional capacity; 10 = maximal functional capacity) for chair rise, standing, walking, stair climbing and descending. In addition, functional capacity was also measured by a chair rise and 15-m walk and stair climbing and descending tests (Gür et al., 2002).

Standing-up From a Chair and 15-m Walking Test: Patients were seated on a chair before a start line. A hand-held stopwatch was started on the command “Go!”, and the patients rose from the chair, without arm support, and walked as fast as possible along a level, unobstructed corridor. The stopwatch was stopped immediately they passed a second mark 15-m from the start.

Two trials, interspersed with a 5 min rest interval, were performed for all functional tests - and the better test result recorded. The reliability coefficients (r) for repeated measures of the functional tests for OA patients varied from 0.97 to 0.99 (Gür et al., 2002).

Sensoriomotor tests

During sensoriomoter tests, subjects were blindfolded and they wore shorts to negate any extraneous skin sensation from clothing touching the knee area.

Joint Position Sense Tests (active and passive): The perceived sense of knee joint position was quantified as the ability to replicate target joint angles using a computerized dynamometer (Cybex 6000, USA). Subjects were blindfolded and seated on the dynamometer at a 105° trunk angle - with the back supported and the knee hanging over the edge of the chair. The lever arm was of the dynamometer passively moved from 90° (0° = knee fully extended) to 1 of 3 randomly allocated target angles of 20, 45 and 70° of knee flexion by the experimenter using a speed of 1°·s-1 - which was maintained for 10 seconds. Subjects then returned the knee to the start position (90° of flexion) and, after a 5-second rest, attempted to reproduce the previously attained target angle passively and actively (speed of 1°·s-1) stopping when they perceived that the angle had been replicated. All subjects completed 3 different target angle replication attempts, with a 30-second rest between each trial. Angular position was continuously recorded by the dynamometer throughout each trial to permit subsequent calculation of the difference between target and replicated angle. No feedback regarding performance was provided. After one practice trial, subjects completed 3 consecutive test trials. The outcome measure used for the proprioception test was an error score calculated as the average absolute difference between the target and replicated angle (in degrees), averaged over the 3 target angle replication attempts.

Weight Bearing Joint Position Test: The protocol for testing knee joint position sense in the full weight bearing position was a modification of that reported by Bullock-Saxton et al. (2001) The test was performed at 15 and 30° of knee flexion. Rotation axis of a standard goniometer was placed on the lateral side of the dominant knee joint when subjects remained standing. The dominant knee was fully extended (0°) at the starting position and moved randomly to the allocated target angles of 15 or 30° of knee flexion - which was maintained for 5 seconds. Subjects then returned the knee to the start position and, after a 5-second rest, attempted to reproduce the previously attained target angles. The outcome measure used for the reposition tests was an error score calculated as the average absolute difference between the target and replicated angle (in degrees), averaged over the 2 target angle replication attempts.

Kinaesthesia: With the subject’s knee at a 45° angle of flexion, the researcher attached the lever arm of the Cybex. The Cybex dynamometer extended or flexed the knee at 1° s-1 until the subject detected passive motion or a change in joint position. The subject was then asked to identify the direction (flexion or extension) of the knee movement. The direction of the trial was randomized, and the researcher recorded both the stop position (threshold to detection of passive motion) and the direction (measured in degrees of angular displacement for each trial). Six randomized tests (three for flexion and three for extension) were conducted on the dominant leg. The outcome measure used for the threshold to detection was averaged over the 3 trials, for each direction, in degrees.

Balance Tests: After one practice trial, subjects completed 3 consecutive test trials for both ‘eyes open’ and ‘eyes closed’ in the following order: 1) Romberg bilateral, 2) unilateral (single leg standing) stance test on both extremities and 3) Tandem stance. All static balance tests were performed on a medium-density polyfoam mat. During ‘eyes open’ balance tests, subjects looked straight ahead at a cross marked at approximately eye level on the wall 2-m away. For bilateral Romberg test, subjects stood on both feet, without arm support. For unilateral Romberg test, subjects stood on the test side limb with their stance foot centred on the mat and with their knee in slight flexion. They were instructed to lift the limb that was not being tested by bending the knee, and holding it at approximately 90° of knee flexion. Once the subjects were in this position, and stated that they were ready, data collection was initiated. For each test balance measurements were performed for a maximum 30 seconds (provided subjects did not move their body or make contact with the ground). Subjects were asked to stand unsupported with their arms at their side. The subjects performed these tests without shoes and socks to negate any extraneous skin sensation from clothing touching the foot area. The outcome measure (time in seconds) used for the balance assessment was averaged over the 2 trials, for each test situation.

Strength tests

The tests were completed on a Cybex 6000 computer-controlled isokinetic dynamometer, as previously described (Gür et al., 2002). Subjects performed a 5 second isometric contraction for each of 4 maximal repetitions at the angular velocity of 0°·s-1 in both legs following three consecutive submaximal warm-up trials for each muscle group. A 3 min rest was allowed between each leg. For the isometric test, 60 and 30° of knee angle were used for quadriceps and hamstring muscles, respectively.

Conventional concentric continuous (reciprocal) isokinetic tests were used (Gür et al., 2002). During the tests, the subjects performed 4 maximal reciprocal flexion-extension repetitions for each angular velocity of 60, 120 and 180°·s-1 for both legs. The concentric tests were performed after the isometric tests. A 20 min rest was allowed between the concentric and isometric tests, and between measures on each leg.

Multi-station exercise program

TR performed a multi-station exercise program (for detail see Appendix). Prior to the multi-station exercise program, in order to warm-up, subjects walked on a treadmill (Woodway, USA) at a speed of 4 km·h-1 for 10 min.

All tests were performed before and after 6 weeks training by the same assessors for both TR and NONTR. Heart rate was recorded during the whole body exercises to determine exercise intensity (Polar Vantage NV telemeters; Polar Electro Oy, Finland) during weeks 1, 3 and 5. An average heart rate was calculated for each individual.

Statistics

Data was analyzed using non-parametric tests. Probability values of less than or equal to 0.05 were considered to be significant, and all tests were two-tailed. To compare groups a Mann-Whitney U- test was used. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed to compare changes from baseline to six weeks. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 10.0.1 for Windows. Data in the Tables are presented means (interquartile ranges).

Results

Patients

There were no significant differences in the tested variables between TR vs. NONTR before training (Tables 1-6). No one (TR) wished to withdraw from training - and all subjects completed the whole training schedule. During the functional exercises mean (±SD) heart rates of subjects for weeks 1, 3, and 5 were 100 (±10), 97 (±8) and 96 (±14) b·min-1, respectively.

Table 1.

Perceived knee pain (VAS score) of patients during daily activities. Data are means (interquartile range).

| Baseline | After 6 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| At night | Training | 4.4 (2.4, 6.7) | 1.9 (.2, 2.6) **†† |

| Non-training | 4.8 (2.8, 6.7) | 4.1 (1.7, 6.4) | |

| After inactivity | Training | 5.0 (3.6, 7.0) | 1.9 (.4, 2.4) **† |

| Non-training | 5.3 (3.5, 7.6) | 4.0 (1.5, 7.0) | |

| Sitting | Training | 4.7 (2.6, 7.4) | 1.8 (.0, 3.1) **† |

| Non-training | 5.0 (2.5, 6.9) | 4.0 (2.8, 5.1) | |

| Chair Rise | Training | 6.0 (3.8, 8.9) | 2.4 (.3, 4.2) **† |

| Non-training | 5.5 (3.6, 7.8) | 4.9 (2.9, 6.6) | |

| Standing | Training | 5.1 (1.3, 8.8) | 2.7 (.4, 4.5) ** |

| Non-training | 6.6 (4.6, 8.5) | 4.6 (1.8, 7.5) ** | |

| Descending stairs | Training | 6.4 (4.0, 8.9) | 2.9 (.6, 4.6) **†† |

| Non-training | 7.5 (6.3, 8.5) | 6.9 (6.2, 8.6) | |

| Stair climbing | Training | 6.1 (5.0, 7.4) | 2.9 (.7, 5.5) **†† |

| Non-training | 6.2 (3.1, 8.7) | 5.6 (4.0, 7.7) | |

| Total | Training | 37.6 (27.1, 51.2) | 16.6 (6.0, 25.0) **†† |

| Non-training | 40.8 (36.1, 47.0) | 34.2 (28.4, 42.9) |

** p < 0.01 compared with baseline value.

† p < 0.05 and

†† p < 0.01 compared with NONTR.

Table 6.

Kinesthesia (the threshold to detection in degrees) test results of subjects. Data are means (interquartile range).

| Baseline | After 6 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion | Training | 2.3 (1.4, 3.0) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.4) *† |

| Non-training | 2.9 (1.6, 4.2) | 2.5 (1.3, 3.5) | |

| Extension | Training | 2.4 (1.7, 3.6) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) *† |

| Non-training | 2.8 (2.3, 3.5) | 2.5 (1.7, 2.9) |

* p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 compared with baseline value.

† p < 0.05 and

†† p < 0.01 compared with NONTR.

Knee pain

Following the exercise program, in TR, perceived knee pain for daily activities decreased significantly (p < 0.01 to p < 0.05; Table 1). The perceived knee pain for daily activities (except for standing) was significantly (p < 0.01 to p < 0.05) lower in TR compared with NONTR following training (Table 1).

The perceived knee pain during functional tests was also significantly (p < 0.01 to p < 0.05) improved in TR compared with baseline (Table 2). In NONTR the perceived knee pain during chair rise and 15-m walk was significantly worse compared with baseline values. The perceived knee pain during all functional tests was significantly lower in TR compared with NONTR following training (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perceived knee pain (VAS score) of patients during functional tests. Data are means (interquartile range).

| Baseline | After 6 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 15-m walk | Training | 3.5 (1.0, 6,9) | 1.6 (.0, 2.7) **†† |

| Non-training | 3.4 (1.7, 5.6) | 3.9 (1.3, 6.3) | |

| Stand-up and 15-m walk | Training | 3.6 (.9, 6.7) | 2.0 (.1, 4.1) *†† |

| Non-training | 3.3 (1.5, 5.4) | 4.7 (2.2, 6.8) * | |

| Chair Rise | Training | 4.1 (.8, 8.1) | 2.1 (.1, 4.7) **† |

| Non-training | 5.9 (3.6, 8.6) | 5.6 (3.4, 8.8) | |

| Descending stairs | Training | 4.5 (1.5, 7.1) | 2.0 (.2, 3.6) **†† |

| Non-training | 5.3 (3.0, 6.6) | 5.0 (2.0, 7.3) | |

| Stair climbing | Training | 3.5 (1.1, 5.8) | 1.8 (.1, 2.9) **†† |

| Non-training | 4.7 (2.9, 7.0) | 4.0 (2.5, 5.1) | |

| Total | Training | 19.3 (7.2, 33.8) | 9.5 (.8, 19.8) **†† |

| Non-training | 22.6 (18.4, 32.3) | 23.2 (13.0, 34.0) |

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01 compared with baseline value.

† p < 0.05

†† p < 0.01 compared with NONTR.

Functional performance

The subjective ratings for daily activities were significantly improved following the exercise program in TR (Table 3). TR had significantly better activity level compared with NONTR after training (Table 3). The time in seconds for functional tests were also significantly improved in TR compared with baseline (Table 4). The most marked changes were observed in descending and ascending stairs. TR had significantly faster performance times for chair rise, descending and ascending stairs compared with NONTR following the 6 week training period (Table 4).

Table 3.

Subjective rating of daily activities. Data are means (interquartile range).

| Baseline | Post-exercise | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 15-m walk | Training | 3.0 (2.0, 5.8) | 8.3 (7.1, 9.5)**† |

| Non-training | 2.8 (1.9, 5.1) | 4.8 (3.2, 7.6)* | |

| Chair Rise | Training | 3.3 (1.2, 6.7) | 8.4 (7.3, 9.9)**† |

| Non-training | 2.9 (2.0, 8.6) | 3.9 (3.0, 7.3) | |

| Standing | Training | 5.8 (2.8, 8.3) | 8.1 (7.4, 9.6)**†† |

| Non-training | 4.1 (2.0, 6.1) | 4.8 (2.6, 7.1) | |

| Descending stairs | Training | 3.5 (2.0, 6.2) | 7.3 (5.6, 9.2)**†† |

| Non-training | 1.9 (1.5, 3.9) | 2.6(1.5, 4.4) | |

| Stair climbing | Training | 4.2 (2.8, 6.2) | 7.3 (5.4, 9.1)**† |

| Non-training | 2.9 (1.1, 4.2) | 4.3 (2.7, 6.0) | |

| Total | Training | 22.4 (15.0, 30.1) | 40.0 (34.2, 44.5)**†† |

| Non-training | 17.6 (10.8, 23.0) | 21.1 (15.7, 28.2) |

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01 compared with baseline value.

† p < 0.05

†† p < 0.01 compared with NONTR.

Table 4.

Time (s) during the functional tests. Data are means (interquartile range).

| Baseline | After 6 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 15-m walk | Training | 10.3 (9.1, 11.8) | 9.4 (8.3, 10.8) ** |

| Non-training | 12.1 (10.6, 13.3) | 11.9 (10.5, 13.1) | |

| Stand-up and 15-m walk | Training | 11.3 (10.7, 12.9) | 10.0 (8.6, 11.5) ** |

| Non-training | 13.3 (11.7, 15.5) | 12.6 (10.8, 14.6) * | |

| Chair Rise | Training | 30.2 (26.8, 34.8) | 26.5 (23.2, 31.9) **† |

| Non-training | 32.8 (28.8, 35.4) | 31.8 (28.9, 33.1) | |

| Descending stairs | Training | 8.1 (6.6, 9.9) | 6.2 (5.2, 6.9) **†† |

| Non-training | 10.9 (6.6, 13.3) | 10.3 (6.6, 10.2) | |

| Stair climbing | Training | 8.2 (7.0, 9.7) | 7.0 (6.0, 8.3) **† |

| Non-training | 9.2 (7.2, 9.5) | 8.9 (7.0, 9.2) | |

| Total | Training | 68.2 (58.6, 74.1) | 59.1 (51.9, 63.6) **†† |

| Non-training | 78.3 (67.5, 93.8) | 75.5 (63.9, 85.3) |

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01 compared with baseline value.

† p < 0.05

†† p < 0.01 compared with NONTR.

Joint position sense

Active and passive knee joint position senses’ error scores (JPS) at 20, 45 and 70° were similar in TR and NONTR before the intervention. After 6 weeks, JPS at all tested angles showed significant improvement for active and passive tests in TR compared with baseline. After 6 weeks, except for the active test at 45° and the passive test at 70°, TR had significantly lower values compared with NONTR (Table 5).

Table 5.

Position sense error scores (degrees) of the patients at 20°, 45° and 70°of knee angles. Data are means (interquartile range).

| Baseline | After 6 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Active 20° | Training | 8.8 (5.8, 12.8) | 5.5 (3.9, 6.2) **†† |

| Non-training | 5.8 (2.8, 8.3) | 10.4 (4.5, 15.0) | |

| Active 45° | Training | 7.4 (4.0, 11.3) | 3.0 (2.0, 3.7) ** |

| Non-training | 6.9 (3.3, 9.5) | 5.6 (3.9, 7.1) | |

| Active 70° | Training | 6.7 (3.9, 10.3) | 3.7 (2.8, 4.5) **† |

| Non-training | 7.2 (2.6, 11.3) | 8.0 (4.0, 10.6) | |

| Passive 20° | Training | 10.1 (3.1, 16.4) | 4.4 (2.1, 6.7) **†† |

| Non-training | 7.0 (2.9, 13.0) | 8.6 (4.6, 13.6) | |

| Passive 45° | Training | 6.8 (4.3, 9.4) | 3.7 (2.3, 5.9) **† |

| Non-training | 6.6 (5.0, 7.4) | 6.3 (3.9, 7.7) | |

| Passive 70° | Training | 6.8 (4.8, 9.7) | 4.5 (3.3, 6.5) * |

| Non-training | 7.7 (3.8, 9.5) | 6.1 (3.2, 7.9) |

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01 compared with baseline value.

† p < 0.05

†† p < 0.01 compared with NONTR.

Kinaesthesia

The threshold to detection in degrees was significantly improved in TR and NONTR for flexion and extension after 6 weeks. TR had a significantly lowered kinaesthesia (degrees) compared with NONTR after 6 weeks (Table 6).

Weight bearing joint position sense

Position error at 15 and 30° of knee flexion improved significantly compared with baseline values in TR. In NONTR there was a no significant change at 15° whereas JPS worsened at 30° of knee flexion compared with baseline values (Table 7). Overall there were no significant differences between TR and NONTR at the end of training.

Table 7.

Weight bearing Joint Position Sense (position error, degrees) test results of subjects. Data are means (interquartile range).

| Baseline | After 6 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 15° | Training | 3.0 (1.8, 3.8) | 1.3 (.8, 1.9) ** |

| Non-training | 4.0 (1.6, 5.4) | 2.9 (1.3, 4.2) | |

| 30° | Training | 3.4 (2.2, 4.0) | 1.5 (1.3, 2.0) ** |

| Non-training | 3.7 (1.6, 5.1) | 3.1 (1.9, 4.4) |

** p < 0.01 compared with baseline value.

Balance tests

The time for Romberg bilateral test performed ‘eyes open’ and ‘eyes closed’ were not significantly changed in either group compared with baseline values (Table 8). However, the times for Romberg unilateral tests performed ‘eyes open’ and ‘eyes closed’ improved in TR compared with baseline values (p < 0.01). These values were significantly higher compared with NONTR after training (Table 8). The time for the Tandem test performed ‘eyes closed’ was significantly improved for TR compared with baseline values. These values were significantly greater compared with NONTR after training (Table 8). However, the Tandem test, performed ‘eyes open’ showed no change compared with baseline values for TR and NONTR after training.

Table 8.

Postural control - time (s) during the balance tests of the patients. Data are means (interquartile range).

| Baseline | After 6 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Romberg bil eyes open | Training Non-training |

30.0 (30.0, 30.0) 30.0 (30.0, 30.0) |

30.0 (30.0, 30.0) 30.0 (30.0, 30.0) |

| Romberg uni eyes open | Training Non-training |

22.7 (15.3, 29.9) 16.3 (6.7, 30.0) |

27.6 (25.3, 30.0) **† 15.3 (5.6, 30.0) |

| Tandem eyes open | Training Non-training |

28.8 (30.0, 30.0) 25.5 (22.1, 30.0) |

29.3 (30.0, 30.0) 24.4 (16.5, 30.0) |

| Romberg bil eyes closed | Training Non-training |

29.5 (30.0, 30.0) 30.0 (30.0, 30.0) |

30.0 (30.0, 30.0) 30.0 (30.0, 30.0) |

| Romberg uni eyes closed | Training Non-training |

4.3 (2.6, 6.0) 4.0 (2.3, 4.2) |

13.3 (6.0, 23.0) **†† 4.5 (2.1, 5.8) |

| Tandem eyes closed | Training Non-training |

12.4 (5.0, 21.4) 10.0 (6.1, 13.7) |

24.4 (17.8, 30.0) **††† 7.8 (3.2, 11.4) |

** p < 0.01 compared with baseline value.

† p < 0.05

†† p < 0.01

††† p < 0.001 compared with NONTR.

bil = bilateral, uni = unilateral.

Muscle strength

After 6 weeks, isometric strength of the quadriceps in TR and hamstring strength in NONTR were significantly (p < 0.05) improved compared with baseline values. There were no significant differences between the groups for isometric quadriceps and hamstring strengths after intervention period. In addition, concentric quadriceps and hamstring strengths of patients in both groups showed no significant change following the training period (Table 9).

Table 9.

Isometric peak torque (Nm) of patients at knee angels of 30° and 60°. Data are means (interquartile range).

| Baseline | After 6 weeks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QUA | 30° | Training | 59 (42, 71) | 71 (50, 90) ** |

| Non-training | 60 (49, 69) | 61 (52, 75) | ||

| 60° | Training | 76 (51, 100) | 103 (66, 125) ** | |

| Non-training | 90 (73, 111) | 90 (71, 112) | ||

| HAM | 30° | Training | 53 (40, 61) | 59 (37, 81) |

| Non-training | 44 (30, 64) | 50 (39, 65) * | ||

| 60° | Training | 41 (29, 49) | 49 (32, 66) * | |

| Non-training | 41 (25, 69) | 41 (35, 53) |

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01 compared with baseline value.

QUA = quadriceps, HAM = hamstring.

Discussion

Reviewing the literature, a pure proprioceptive program including several balance exercises, has not been used in patients with severe knee OA. We expected that the program would lead to an improvement in proprioceptive/balance capabilities in TR and therefore to improvements in functional capacity and a decrease in perceived knee pain. In summary, TR showed a marked decrease in perceived pain scores, and increases in functional capacity together with a significant increase in postural control. In addition, despite their severe disability the patients showed a remarkable compliance both with the training program and with the evaluation protocol, participating in all of the training and assessment sessions.

O'Reilly and co-workers (1999) used isometric quadriceps, isotonic quadriceps and hamstring exercises, and dynamic stepping exercise daily for 6 months in OA patients. They evaluated pain perceived during walking, ascending-descending stairs (using the visual analogue scale) and physical function score and found that they were improved by 20.9, 18.6, and 17.4 %, respectively, in an exercise group (O'Reilly et al., 1999). In the present study, the perceived pain score during walking and stair climbing, and the mean physical function score improved 61.5, 62.1, and 62.5% respectively following training. Although differences in methods limit the comparison between two studies, there was a greater magnitude of change in the present study.

Fisher and colleagues (1991) used isometric, in addition to isotonic, training in a program lasting 16 weeks in a similar group of patients (knee OA). They reported that improvements in 15-m walk time and functional performance were approximately 9% for both groups after an 8 week intervention. After 16 weeks improvements were approximately 12 and 25%, respectively (Fisher et al., 1991). In the present study the improvement in 15-m walk time was similar to that reported by Fisher et al. (1991) with a value of 8.7±1.0% - but the subjective rating in daily activities was double (61.4±17.6%) compared with values reported by Fisher and colleagues (1991).

In the study reported by Fisher and colleagues (1991), the most important improvements were observed in perceived pain during walking, standing, rising from a chair and climbing stairs with values of 30 and 10% for 16 and 8 weeks training respectively. In contrast these parameters improved 62.5 ± 14.3%, as a total score, after training in the present study. In a further study Fisher and colleagues (1993) investigated the effects of a rehabilitation program, which included stretching and resistance exercise 3 days a week for 3 months, on functional performance and perceived pain in subjects with knee OA. Improvements in function and perceived pain were greater in the present study compared with a 3 month program (Fisher et al., 1993).

Rogind et al. (1998) have investigated the effects of a physical training program, employed twice a week for 3 months, on general fitness, lower extremity muscle strength, agility, balance and coordination of bilateral knee OA patients. The program comprised lower leg progressive repetitive exercises, flexibility exercises of the lower extremities, coordination and balance exercises. From baseline to 3 months, only perceived pain at night and muscle strength showed significant improvements. Time to walk 20-m, stair climbing, postural stability and balance were unchanged by 3 months of training. In addition, they observed an increased number of knees with effusions after intervention and they reported that the intervention led to an increase in the disease. Lack of proprioceptive sensation probably causes altered gait and non-physiological joint loading - which results in disability and further symptoms in OA patients (Barret et al., 1991; Stauffer et al., 1977). Stauffer et al. (1977) suggested that deterioration in proprioception might be a major factor, and that the abnormal gait is an effort to maximize proprioceptive input. Hu and Woollacott (1994) suggested that general exercise programs are less effective than programs that target a specific system (e.g. visual, vestibular, somatosensory) that functions to maintain balance. The present study provides evidence that short-term proprioceptive/ balance training improves balance and proprioception in older OA patients, as emphasized by Hu and Woollacott (1994). Therefore, the reason for the failure of many exercise studies including Rogind and co-workers (1998) to elicit significant changes may be the lack of specificity in the training program.

When we compared the results of the present study with previous studies, which used traditional/ aerobic and strength exercises for OA (Beals et al., 1985; Chamberline et al., 1982; Fisher et al., 1991; 1993; Minor et al., 1989), the functions and symptoms of the patients in these earlier studies did not improve as markedly as similar measures found in the present study. In the present study, the most marked change was observed in descending and climbing stairs times with values of 21 and 15% respectively. These results are particularly important considering that the ability to descend and ascend stairs is impaired in OA compared with healthy subjects (Hurley et al., 1997). In addition, it should be noted that the patients in TR suffered less perceived pain in their knee even though they moved faster during the tests after training. Our results also show that improvements in functional capacity and perceived knee pain are not necessarily associated with improved knee strength.

Hurley and Scott (1998) investigated the effects of an exercise regime on quadriceps strength and proprioceptive acuity and disability in patients with knee OA. The exercises included isometric quadriceps contractions, a static exercise cycle, isotonic knee exercise using therapeutic resistance bands, functional (sit-stand, steps, step-down) and balance/co-ordination exercises (unilateral stance and balance boards). Following 5 weeks of training, they found that quadriceps strength, joint position sense, aggregate functional performance time and Lequesne Index (as a subjective assessment of perceived knee pain) improved significantly in the exercise group by 36.3, 12.9, 13.7 and 31.8% respectively. These values were significantly different compared with a control group - except joint position sense. In the present study, average joint position sense for active and passive tests, total time for functional tests and total visual analog score (VAS) for perceived knee pain during daily activities improved 32.8, 38.2, 12.9 and 62.5% following training. Again these changes were significantly different compared with our control group. When compared with Hurley’s results, our patients had a similar improvement in functional performance time and more than double the improvement in joint position sense and pain score after training. The patients in the present study performed only proprioceptive and balance exercises and recorded large improvements. Thus compared with more sophisticated programs (Hurley and Scott, 1998) for improving function in OA - it may be beneficial to target improved balance and coordination (present study).

Barrett et al. (1991) compared knee joint position sense among 81 normal, 45 OA patients and 21 patients who had replacement surgery. In this earlier study the volunteers’ legs were moved passively in the range 0 to 30° in 10 different predetermined positions of flexion - and the individual was subsequently asked to represent the perceived angle of flexion on a visual analogue model. Average JPS error score was 5° in the healthy and 7° in OA patients. In the present study the active error score for 20° knee flexion angle was 8.8±4.4° for patients with a mean age of 60 years and improved to 5.5±2.3° with training. Therefore, it may be speculated that knee position sense can be improved in OA after training to a level attained by age-matched healthy subjects.

Daily activities like walking, ascending or descending stairs are weight bearing; knee proprioception was generally tested under a non-weight bearing condition in these previous investigations. In the present study, knee joint proprioception was investigated under a weight bearing condition. Petrella et al. (1997) investigated knee joint proprioception under weight bearing condition in young volunteers and in physically active and sedentary older volunteers. They reported that the mean active angle reproduction errors at the test angles that ranged 10 to 60° of knee flexion were 2.0 ± 0.5°, 3.1 ± 1.1° and 4.6 ± 1.9° for young, physically active and sedentary older people respectively. Bullock-Saxton et al. (2001) also measured the joint position reproduction error under full weight bearing condition in healthy young (20-35 years old), middle- aged (40-45 years old) and older (60-75 years old) subjects. They reported values of 1.9 ± 0.8°, 2. 0 ± 0.7° and 2.2 ± 0.9°, for the three groups respectively, for a test angle between 20 and 35° of knee flexion. In our subjects it was 3.0 ± 1.5° and 3.4 ± 1.5° at the angles of 15° and 30° of knee flexion, respectively, before training and improved to 1.3 ± 0.6° and 1.5 ± 0.6°, respectively, after training. Therefore knee position sense under weight bearing condition can be improved in OA to the level of young healthy subjects using the training program described herein.

The balance test performed ‘eyes open’ and ‘eyes closed’ reflects the reorganization of the different components of postural control. In the elderly, visual sensors are of major importance in postural control, while vestibular and proprioceptive afferents are less used (Gauchard et al., 1999; Perrin et al., 1999). Hence the ‘eyes open’ and ‘eyes closed’ data obtained in the present study allow an appreciation of the respective “weight ”of the various balance sensors and their interactions in postural and motor control. In the present study, we observed that ‘eyes closed’ Romberg unilateral and Tandem test times were improved 208 and 164% respectively in TR. The magnitude of these changes, even though the ‘eyes closed’ condition was very difficult for this cohort, suggests that the training program used in the present study is clinically important for balance. It can be also speculated that, in order to retain a proper balance with ‘eyes closed’, our TR might have compensated for the visual deprivation by an increased usage of other sensors and/or corrected their posture by adopting a more appropriate balance strategy. Several clinical trials have utilized time during leg stance to examine the effects of exercise on balance in healthy older adults. However, previous studies have generally used strength (Brown and Holloszy, 1991; MacRae et al., 1994; Topp et al., 1993) or fitness training (Hopkins et al., 1990; Messier et al., 2000) - which did not include specific exercises that target balance. Although these studies used longer exercise sessions ranging from 12 weeks to 18 months in healthy older people, the effect of training on the balance was negligible. The reason for the apparent failure of many earlier exercise studies to elicit significant changes in balance may be the lack of specificity of the training regimen as mentioned above.

Gauchard et al. (1999) reported that regular proprioceptive activities such as yoga improve postural control whereas bioenergetic activities such as walking, swimming and cycling increase lower leg muscular strength but not necessarily dynamic balance in elderly individuals. Gaucher et al. (1999) also reported that muscular strength is not a major factor for ‘eyes open’ and ‘eyes closed’ conditions, and improved muscular control nevertheless helps to retain proper balance in the ‘eyes closed’ condition. Similarly, Hurley et al. (1997) suggested that factors other than muscle strength have important influences on patients’ postural stability. In the present study, although the improvements in strength were relatively poor balance control was significantly improved. Therefore, as supported by earlier work (Gaucher et al., 1999; Hurley et al., 1997), the improvements in perceived knee pain and lessened disability in our patients may, at least in part, relate to factors other than muscle strength.

Conclusions

The findings of the present study suggest that using a pure proprioceptive/balance exercise program it is possible to improve functional capacity, postural control and decrease perceived knee pain in patients with bilateral knee osteoarthrosis. The exercise regime used in the present study was as effective as previous studies (O'Reilly et al., 1999; Fisher et al., 1991; Fisher et al., 1993; Beals et al., 1985; Chamberline et al., 1982; Minor et al., 1989), but of much shorter duration and utilized unsophisticated, inexpensive equipment which is available in most physiotherapy departments. Therefore, the incorporation of this exercise program into clinical practice is readily feasible.

Biographies

Ufuk SEKIR

Employment

Ass. Prof. Sports Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Uludag Univ., Bursa, Turkey.

Degree

MD

Research interests

Proprioception, ACL rehabilitation, osteoarthritis and exercise.

E-mail: ufuksek@hotmail.com

Hakan GÜR

Employment

Prof., Sports Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Uludag Univ., Bursa, Turkey.

Degree

MD, PhD

Research interests

Isokinetic, menstrual cycle and exercise, circadian variations, ACL rehabilitation, osteoarthritis and exercise, smoking and exercise, ageing and exercise.

E-mail: hakan@uludag.edu.tr

APPENDIX

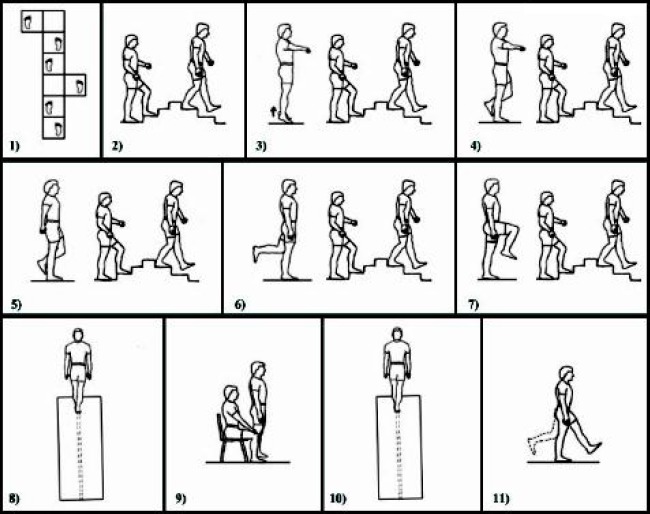

To improve balance and proprioception eleven exercises were performed in the following order (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Illustration of the exercises.

Walk forward through 6 boxes (50cm x 50cm) on one-foot (in-in-out to right-in-in-out to left).

Stair-up and -down a regular 3 steps staircase (17 cm high and 23 cm wide).

Stand with feet approximately shoulder width apart and extend arms out slightly forward and lower than the shoulder. Lift both heels off the floor and try to hold the position for 10 seconds. Followed by climbing a regular 3 steps staircase (17 cm high and 23 cm wide), -up and -down.

Standing with feet side by side, hold arms in the same position as described in the previous exercise. Place one foot on the inside of the opposing ankle and try to hold the position for 10 seconds. Followed by climbing a regular 3 steps staircase (17 cm high and 23 cm wide), -up and -down.

Repeat the exercise 3 with hands behind the back. Followed by climbing a regular 3 steps staircase (17 cm high and 23 cm wide), -up and -down.

Perform a one-legged stand with one foot raised to the back (the non-weight bearing knee flexed at 90°). Try to maintain the position for a minimum of three seconds. The long-term goal is to decrease the need for balance support and to hold the position for 10 seconds. However, as necessary, the hands are allowed to contact the support apparatus (a standard chair). Followed by climbing a regular 3 steps staircase (17 cm high and 23 cm wide), -up and -down.

Perform the same exercise as above, but raise one foot to the front (the non-weight-bearing knee flexed and lifted approximately as high as the hip). Followed by climbing a regular 3 steps staircase (17 cm high and 23 cm wide), -up and -down.

Walk heel-to-toe along a 3m line marked on a medium-density polyfoam mat.

Rising from a standard chair (4 times) without arm support.

Walk heel-to-toe along a 3-m line marked on a medium-density polyfoam mat.

With the knee straight but not hyperextended, execute single (relatively small) leg raises to the front, then back. Continued alternating front to back.

Patients performed 11 different exercises (above) once during weeks 1 and 2, twice during weeks 3 and 4 and three times during weeks 5 and 6. In addition, subjects were instructed to stand in 6 different conditions for static exercises (exercise 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 11) as follows:

Week 1: on a firm surface, eyes open, head neutral.

Week 2: on a firm surface, eyes closed, head neutral.

Week 3: on a firm surface, eyes open, head tilted back.

Week 4: on a firm surface, eyes closed, head tilted back.

Week 5: on a foam surface, eyes open, head neutral.

Week 6: on a foam surface, eyes closed, head neutral.

References

- Altman R., Asch E., Bloch D. (1986) The American College Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis and Rheumatism 29, 1039-1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badley E.M., Tennant A. (1992) Changing profile of joint disorders with age: findings from a postal survey of the population of Calderdale, West Yorkshire, United Kingdom. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 51, 366-371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barret D.S., Cobb A.G., Bentley G. (1991) Joint proprioception in normal, osteoarthritic and replaced knees. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British Volume) 73B, 53-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals C.A., Lampman R.M., Banwell B.F., Braunstein E.M., Albers J.W., Castor C.W. (1985) Measurement of exercise tolerance in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. The Journal of Rheumatology, 12, 458-461 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlsma J.W.J, Dekker J. (2005) A step forward for exercise in the management of osteoarthritis. Rheumatology 44, 5-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham T.B., Krameri J.F., Kirkley A., Inglis T., Spaulding S.J., Vandervoort A.A. (2001) Association among neuromuscular and anatomic measures for patients with knee osteoarthritis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 82, 1115-1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M., Holloszy J.O. (1991) Effects of a low intensity exercise program on selected physical performance characteristics of 60- to 71- year olds. Aging 3, 129-139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock-Saxton J.E., Wong W.J., Hogan N. (2001) The influence of age on weight-bearing joint reposition sense of the knee. Experimental Brain Research 136, 400-406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberline M.A., Care G., Harfield B. (1982) Physiotherapy in osteoarthritis of the knees. A controlled trial of hospital versus home exercises. International Journal of Rehabilitative Medicine 4, 101-106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson D.T. (1990) The epidemiology of knee osteoarthritis: results from the Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 20, 42-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher N.M., Pedegast D.R., Gresham G.E., Calkins E. (1991) Muscle rehabilitation: its effect on muscular and functional performance on patients with knee OA. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 72, 367-374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher N.M., Gresham G.E., Abrams M., Hicks J., Hornigon D., Pendergest D.R. (1993) Quantitative effects of physical therapy on muscular and functional performance in subjects with osteoarthritis of the knees. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 74, 840-847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick R., McCloskey D.I. (1994) Proprioceptive, visual and vestibular thresholds for the perception of sway during standing in humans. The Journal of Physiology 478, 173-186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauchard G.C., Jeandel J., Tessier A., Perrin P.P. (1999) Benefical effect of proprioceptive physical activities on balance control in elderly human subjects. Neuroscience Letters 273, 81-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur H., Cakin N., Akova B., Okay E., Kucukoglu S. (2002) Concentric versus combined concentric-eccentric isokinetic training: effects on functional capacity and symptoms in patients with osteoarthrosis of the knee. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 83, 308-316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan B.S., Mockett S., Doherty M. (2001) Static postural sway, proprioception, and maximal voluntary quadriceps contraction in patients with knee osteoarthritis and normal control subjects. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 60, 612-618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins D.R., Murrah B., Hoeger W.W., Rhodes R.C. (1990) Effect of low-impact aerobic dance on the functional fitness of elderly women. Gerontologist 30, 189-192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M.H., Woollacott M.H. (1994) Multisensory training of standing balanve in older adults: I. Postural stability and one-leg stance balance. Journal of Gerontology 49, M52-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley M.V. (2003) Muscle dysfunction and effective rehabilitation of knee osteoarthritis: What we know and what we need to find out. Arthritis and Rheumatism 49, 444-452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley M.V., Scott D.L. (1998) Improvements in quadriceps sensorimotor function and disability of patients with knee osteoarthritis following a clinically practicable exercise regime. British Journal of Rheumatology 37, 1181-1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley M.V., Scott D.L., Rees J., Newham D.J. (1997) Sensorimotor changes and functional performance in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 56, 641-648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen J.A., Kujala U.M. (2004) Exercise therapy for people with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 14, 138-142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan J.R., Silman A.J. (1987) Epidemiological, sociological and environmental aspects of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthrosis. Bailliere’s Clinical Rheumatology 1, 467-489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koralewicz L.M., Engh G.A. (2000) Comparison of proprioception in arthritic and age-matched normal knees. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 82A, 1582-1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord S.R., Lloyd D.G., Li S.K. (1996) Sensori-motor function, gait patterns and falls in community-dwelling women. Age and Ageing 25, 292-299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRae P.G., Feltner M.E., Reinsch S. (1994) A 1-year exercise program for older women: Effects on falls, injuries, and physical performance. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity 2, 127-142 [Google Scholar]

- Mankin H.J. (1989) Clinical features of osteoarthritis. Textbook of Rheumatology. Kelley W.N., Harris E.D., Ruddy S.Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1480-1500 [Google Scholar]

- Marks R. (1994a) An investigation of the influence of age, clinical status, pain and position sense on stair walking in women with osteoarthrosis. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 17, 151-158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks R. (1994b) Correlation between knee position sense measurements and disease severity in persons with osteoarthritis. Revue du Rhumatisme (English ed.) 61, 365-372 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier S.P., Royer T.D., Craven T.E., O'Toole M.L., Burns R., Ettinger W.H., Jr. (2000) Long-term exercise and its effect on balance in older, osteoarthritic adults: results from the Fitness, Arthritis, and Seniors Trial (FAST). Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48, 131-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor M.A., Hewett J.E., Webel R.R., Anderson S.K., Kay D.R. (1989) Efficacy of physical conditioning exercise in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 32, 1396-1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly S.C., Muir K.R., Doherty M. (1999) Effectiveness of home exercise on pain and disability from osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomised controlled trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 58, 15-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin P.P., Gauchard G.C., Perrot C., Jeandel C. (1999) Effects of physical and sporting activities on balance control in elderly people. British Journal of Sports Medicine 33, 121-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrella R.J., Lattanzio P.J., Nelson M.G. (1997) Effect of age and activity on knee joint proprioception. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation 76, 235-241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roddy E., Zhang W., Doherty M., Arden N.K., Barlow J., Birrell F., Carr A., Chakravarty K., Dickson J., Hay E., Hoise G., Hurley M., Jordan K.M., McCarthy C., McMurdo M., Mockett S., O'Reilly S., Peat G., Pendleton A., Richards S. (2005) Evidence-based recommendations for the role of exercise in the management of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee - the MOVE consensus. Rheumatology 44, 67-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogind H., Bibow-Nielsen B., Jensen B., Moller H.C., Frimodt-Moller H., Bliddal H. (1998) The effects of a physical training program on patients with osteoarthritis of the knees. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 79, 1421-1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer R.N. Chao E.Y.S., Gyory A.N. (1977) Biomechanical gait analysis of the diseased knee joint. Clinical Orthopaedics 126, 246-255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanik C.B., Rubash H.E., Barrack R.L., Lephart S.M. (2000) The role of proprioception in patients with DJD and following total knee arthroplasty. Proprioception and neuromuscular control in joint stability. Lephart S.M., Fu F.H.United States: Human Kinetics; 323-339 [Google Scholar]

- Topp R. Mikesky A. Wigglesworth J. Holt W.Jr., Edwards J.E. (1993) The effect of a 12-week dynamic resistance strength training program on gait velocity and balance of older adults. Gerontologist 33, 501-506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WMADH (2000) World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The Journal of the American Medical Association 20, 3043-3045 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]