Abstract

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a complex medical condition affecting multiple systems within the body. Occupational health nurses will frequently encounter these patients in health care settings. The most commonly used case definition requires an individual to have six or more months of fatigue and the presence of at least four of eight minor symptoms(Fukuda, et al., 1994). In addition, there are many health and psychological conditions, including severe obesity as defined as body mass index equal to or greater than 40 kg/m2, which, when present, exclude patients from receiving a diagnosis of CFS. Obesity has been correlated with levels of fatigue, increased sleep problems and has been significantly associated with reduced satisfaction with general health functioning and vitality (Lim, Thomas, Bardwell, & Dimsdale, 2008). The current study investigated weight trends over time in a community-based sample of individuals with CFS and healthy controls. It further investigated the impact of co-morbid weight issues on a number of health and disability outcomes with a subset of overweight individuals. Overweight and obese individuals with CFS demonstrated poorer functioning than controls that were similarly weighted. One participant was excluded because she had gained weight at follow up and her BMI was > 40 kg/m2. The implications of these findings for health care workers are discussed.

Keywords: chronic fatigue syndrome, Myalgic encephalomyelitis, obesity, exclusionary factors

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a complex medical condition that affects over 800,000 adults in the United States (Jason et al., 1999), and estimates of prevalence are higher among health care workers such as nurses (Jason, Wagner, Rosenthal, et al., 1998). CFS is a highly debilitating illness that is poorly understood and difficult to diagnose since there is no substantiated cause. Although the pathophysiology remains elusive, some researchers suggest CFS is a heterogeneous condition with different pathophysiological abnormalities (Afari & Buchwald, 2003). There is growing evidence to support biological abnormalities in a number of different domains, as in the central nervous system (Lange, DeLuca, Maldjian, Lee, Tiersky, & Natelson, 1999; Natelson, Cohen, Brassloff, & Lee, 1993), neuroendocrine regulation (Hickie et al., 2006; Demitrack, et al., 1991) and immune system activation (Maher, Klimas, & Fletcher, 2005; Komaroff & Buchwald, 1998). Difficulty in replicating many of these findings has in part been due to the heterogeneous nature of the CFS case definition (Fukuda et al., 1994), which results in incomparable patient samples being used across research sites.

The most widely used case definition requires a patient to have six or more months of chronic, unexplained fatigue and at least four out of eight of the following minor symptoms: impaired memory or concentration, post-exertional malaise, unrefreshing sleep, muscle pain, multi-joint pain, headaches, sore throat and tender lymph nodes. Additionally, in order to receive a diagnosis of CFS, patients must not have certain medical and psychological conditions that could cause similar symptoms. The case definition suggests that an active exclusionary condition be resolved before receiving a diagnosis. Severe obesity, as defined by a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 45 kg/m2, is one medical condition considered exclusionary (Fukuda et al., 1994). Reeves and colleagues (2003) revised the Fukuda et al. case definition and changed the BMI cut-off point for exclusionary obesity from BMI ≥ 45 kg/m2, to BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2, resulting in a lower threshold for being more easily excluded from a diagnosis of CFS due to weight issues.

In recent decades, obesity has become a rising concern in the United States due to rapidly increasing prevalence rates. Between 1980 and 2002, the national prevalence of obesity in adults aged 20 years or older doubled. During the same period, the prevalence of overweight children aged six to nineteen tripled (Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, McDowell, Tabak, & Flegal, 2006). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that more than one-third of U.S. adults (35.7%) and 17% of youth aged two to 19 are obese (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012). Many studies document obesity as a risk factor for a number of health conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer (Fine et al., 1999). In addition, obesity has an association with some symptoms similar to those of CFS, such as increased levels of fatigue, increased sleep problems (Lim, Thomas, Bardwell, & Dimsdale, 2008), increased levels of pain (Fine et al., 1999) and reduced physical functioning and vitality (Lim, Thomas, Bardwell, & Dimsdale; Katz, McHorney, and Atkinson, 2000; Fine et al., 1999). A cross-sectional report examining health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in overweight and obese patients with chronic conditions typical of those seen in a general medical practice, found these patients had significantly lower HRQOL across physical functioning, health perceptions, and vitality domains when compared to non-overweight patients (Katz, McHorney & Atkinson, 2000).

Few studies have examined the association between weight gain/obesity and CFS. As previously mentioned, revisions to the Fukuda et al. CFS case definition decreased the BMI cutoff point for exclusionary obesity from BMI ≥ 45 kg/m2, to BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 (Reeves et al., 2003), resulting in a lower weight threshold for being excluded from a diagnosis. This change to the BMI criteria was made because Reeves and colleagues (2003) believe obesity, as defined by BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2, to be “a more inclusive contributing factor to explain chronic fatigue” (p. 3). This change to the obesity exclusionary criteria was made to eliminate individuals with a lower threshold for weight issues from the case definition. However, due to the debilitating nature of CFS, patients have been known to substantially reduce their occupational, social, educational, and personal activities (Jason et al., 2011; Hardt, Buchwald, Wilks, Sharpe, Nix & Egle, 2001; Komaroff et al., 1996), which over time may result in the type of weight gain that can become an exclusionary factor of CFS. Furthermore, there is growing evidence that people with CFS may have aerobic metabolic dysfunction causing pathological fatigue and post-exertional malaise (Vermeulen, Kurk, Visser, Sluiter, & Scholte, 2010; VanNess, Snell & Stevens, 2007; Jammes, Steinberg, Mambrini, Bregeon & Delliaux, 2005; McCully & Natelson, 1999). Both fatigue and post-exertional malaise can lead to weight gain, as patients who are severly fatigued may not have the energy required to exercise (De Becker, Roeykens, Reynders, McGregor & De Meirleir, 2000). Additionally, post-exertional malaise, a cardinal symptom of CFS, may intensify other symptoms and causes a patient’s body to recover slower than a healthy person’s after exercise (VanNess, Stevens, Bateman, Stiles, & Snell, 2010; VanNess, Snell & Stevens, 2007).

Occupational health nurses are involved in education, research, public policy and practice for a variety of clinical conditions. As critical workers within the health care community, occupational health nurses will often see patients with both chronic fatigue as well as chronic fatigue syndrome (Jason & Wagner, 1998). As one example of the work in health care settings, Jason, Muldowney, and Torres-Harding (2008) and Jason et al. (1999) provided examples of how patients could be managed in clinical settings by monitoring and managing their available energy levels. In working with patients, it is also likely that some might gain weight from inactivity, and it might be unclear what role the additional weight might have for the patient, including treatment whether they still meet criteria for the case definition. Following patients longitudinally would provide some helpful insights regarding the role of weight gain over time. Therefore, the current study examined the impact of co-morbid weight issues on physical functioning and other health related symptoms among people with CFS compared to similarly weighted controls, in order to clarify the appropriateness of obesity as an exclusionary factor. Individuals were evaluted at two assessment points over an approximate 10 year peirod of time. We therefore examined weight issues at a Wave 1 and then at a Wave 2 for the same patients, some of whom had CFS and others who did not. It was hypothesized that people with CFS would be significantly more impaired than their similarly weighted counter parts, suggesting that CFS symptoms and the associated functional impairment cannot be accounted for solely by obesity.

Methods

The data presented in the current study derive from a larger community-based epidemiology study of CFS. In Wave 1, we telephoned a diverse sample of 28,673 adults to assess for symptoms of CFS using the CFS Screening Questionnaire(Jason, et al., 1997). The pool of participants contacted were randomly selected from several Chicago neighborhoods in order to select for culturally and ethnically diverse individuals of varied socioeconomic status. To contact participants, random phone numbers with valid Chicago prefixes were generated by Survey Sampling Incorporated. Interviewers screened a random sample of adults by telephone using procedures developed by Kish (1965) to select one adult from each household to interview.

Next, 213 respondents underwent a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) to assess for current and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses, and a team of physicians completed thorough medical examination and structured medical history report (See Jason et al., 1999 for more details). A team of physicians was employed to make these diagnostic decisions. Wave 2 was completed 10-years later and follow-up data were obtained for 108 individuals (See Jason et al., 2011 for more details).

Sample

In the present study, 38 individuals with body mass index (BMI) data at both baseline (Wave 1) and 10-year follow-up (Wave 2) were included for analysis. Fifteen individuals were excluded from the current study for incomplete BMI data. Individuals who indicated that they experienced six or more months of chronic fatigue and four or more minor symptoms (e.g. sore throat, muscle pain, unrefreshing sleep; Fukuda et al., 1994) were defined as having CFS following physician assessment (n=20). These individuals had been confirmed as having CFS by physicians following medical and psychiatric examinations (see Jason et al., 2011 for more details). The remaining participants who screened negative for CFS or chronic fatigue were defined as controls (n=18).

Measures

CFS Screening Questionnaire

The CFS Screening Questionnaire (Jason et al., 1997) was used to assess participants’ socio-demographic characteristics (i.e., age, ethnicity, gender, occupation, socioeconomic status, etc.) and CFS symptomatology. This instrument demonstrates good test-retest and inter-rater reliability, and is able to distinguish people with CFS from healthy individuals (Jason et al., 1997). In addition, Hollingshead’s (1975) revised scoring rules, developed and validated by Wasser (1991), were used to operationalize socioeconomic status.

Fukuda criteria

A case of CFS is defined as six or more months of chronic and unexplained fatigue, the co-occurrence of four or more minor symptoms (memory and concentration impairment, sore throat, tender or swollen lymph nodes, muscle pain, multi-joint pain without swelling or redness, headaches, unrefreshing sleep, and post-exertional malaise lasting more than 24 hours), the absence of other illnesses that might cause the chronic fatigue, and this illness must cause substantial reductions to an individual’s personal, social, and occupational functioning (Reeves et al., 2003; Fukuda et al. 1994).

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Body mass index is an index used to estimate an individual’s percentage of body fat. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). The World Health Organization’s International classification of adult weight according to BMI was used. Individuals with a BMI between 18.5 kg/m2 and 24.9 kg/m2 were classified as normal. Those with a BMI between 25 kg/m2 and 29.9 kg/m2 were classified as overweight. Those who had a BMI between 30 kg/m2 and 39.9 kg/m2 were classified as obese. Severely obese individuals had a BMI greater or equal to 40 kg/m2. BMI is the most widely used measure to diagnose obesity. Cut-offs of BMI (≥30 kg/m2) has shown good specificity, but low sensitivity (Romero-Corral et al., 2008) in diagnosing obesity.

Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)

The SF-36 (Ware, Snow, & Kosinski, 2000) is a reliable and valid self-report measure that assesses general health and disability, including levels of physical and mental functioning. It is made up of eight subscales measuring different domains of disability: Physical Functioning, Social Functioning, Role-Physical, Role-Emotional, Vitality, Bodily Pain, General Health, and Mental Health. Higher scores on the SF-36 indicate better health or less impact of health on functioning. The SF-36 has shown adequate internal consistency, discriminant validity and substantial differences between clinical and non-clinical populations in the pattern of scores (McHorney, Ware, & Raczek, 1993).

Krupp Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS)

The Krupp Fatigue Severity Scale (Krupp, LaRocca, Muir-Nash, & Steinberg, 1989) was used to assess fatigue severity and related functional impairments. This is a nine-item Likert-scale. Individuals select a level of agreement to fatigue related statements. The mean score is calculated and higher scores indicate higher levels of impairment as a result of fatigue. The scale demonstrated sufficient internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha between .81 and .89, test-retest reliability, and concurrent validity.

Statistical Analyses

The statistical software package used for data analysis was PASW for Windows, version 18.0. Chi-square analyses were used to assess categorical sociodemographic differences between overweight/obese CFS and control groups, as well as the presence of Fukuda symptoms. Independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine differences on continuous sociodemographic variables, as well as SF-36, FSS, and FS scores. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to determine whether there were significant differences between CFS and control overweight/obese groups on a number of health outcomes over 10 years.

Results

Weight Change Trajectory

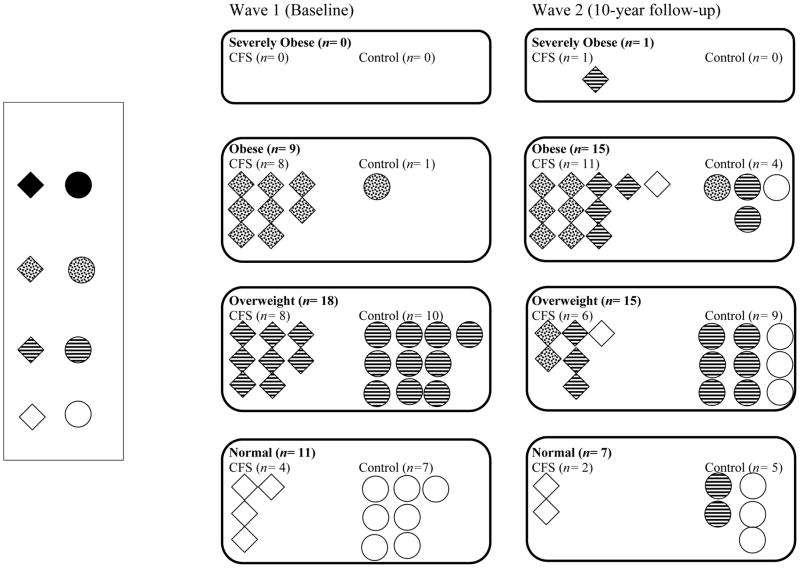

Figure 1 illustrates the weight change trajectory of individuals with CFS and controls from Wave 1 (baseline) to Wave 2 (10-year follow-up). The individuals in the CFS and control groups were placed in overweight categories according to their BMI at baseline. The overweight BMI cut-off point (BMI ≥ 25kg/m2) is consistent with WHO International weight guidelines. At Wave 1, more than half of the individuals in both groups had a BMI higher than 25kg/m2 (M = 26.54, SD = 4.11). Of 20 individuals diagnosed with CFS at baseline, one person was excluded from a diagnosis at the 10-year follow-up due to severe obesity (BMI = 40 kg/m2).

Figure 1.

Participant weight changes flow chart from baseline to 10-year follow up.

Overweight CFS and Control Group Comparisons

Overweight CFS and control groups were compared on a number of socio-demographic items to assess any observable differences between these two groups. The mean age of the study population was 40 years (range 20–64 years) at baseline. Table 1 demonstrates that both overweight groups are comparable on sociodemographic items and there are no significant differences between these two groups, aside from CFS status. The overweight CFS group and the overweight control group were comparable in terms of race, gender, marital status, occupational status, educational status, parental status, age, socioeconomic status and BMI at both Wave 1 and Wave 2.

Table 1.

Demographic Information on Wave 1 CFS and Control overweight Groups (N=27)

| CFS Overweight (n=16) n (%) |

Control Overweight (n=11) n (%) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | .14 | ||

| Black | 2 (12.5) | 3 (27.3) | |

| White | 7 (43.8) | 7 (63.6) | |

| Latino/a | 7 (43.8) | 1 (9.10) | |

| Gender | .68 | ||

| Female | 10 (62.5) | 6 (54.5) | |

| Male | 6 (37.5) | 5 (45.5) | |

| Marital Status | .54 | ||

| Married | 5 (31.3) | 5 (45.5) | |

| Separated/Widowed/Divorced | 5 (31.3) | 4 (36.4) | |

| Never Married | 6 (37.5) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Work Status | .59 | ||

| Disability/Unemployed/Retired | 3 (18.8) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Student/Homemaker | 4 (25.0) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Part-time | 2 (12.5) | 2 (18.2) | |

| Full-time | 7 (43.8) | 7 (63.6) | |

| Education Level | .24 | ||

| High School Degree/GED/Less | 6 (33.3) | 3 (21.4) | |

| Some College/Special Training | 4 (22.2) | 5 (35.7) | |

| College/Graduate Degree | 8 (44.4) | 6 (42.9) | |

| Parental Status | .23 | ||

| No | 11 (68.8) | 5 (45.5) | |

| Yes | 5 (31.3) | 6 (54.5) | |

|

| |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| Age | 38.25 (13.37) | 47.36 (10.10) | .19 |

| Socioeconomic Status (Hollingshead) | 39.75 (18.05) | 49.64 (11.15) | .09 |

| Body Mass Index | 29.39 (2.95) | 27.38 (2.44) | .58 |

Table 2 longitudinally compares overweight CFS and control groups on a number of health outcomes. There was a significant main effect of time for BMI, F (1, 25) = 4.47, p = .05, indicating that both groups experienced significant weight gain from Wave 1 to Wave 2. Additionally, analyses reveal a main effect of group for BMI, F (1, 25) = 7.41, p = .01, such that the overweight/obese CFS group has a mean BMI that is significantly higher than the overweight control group.

Table 2.

Wave 1CFS and Control Overweight Groups: Health Outcomes at Wave 1 and Wave 2 (N= 27)

| Wave 1 M (SD) |

Wave 2 M (SD) |

Effects | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Category | |||

| Body Mass Index | ||||

| CFS Overweight (n= 16) | 29.39 (2.95) | 32.19 (4.12) | * | * |

| Control Overweight (n= 11) | 27.38 (2.44) | 28.00 (4.36) | ||

| SF-36 | ||||

| Physical Functioning | ||||

| CFS Overweight (n= 13) | 59.62 (21.16) | 64.52 (24.62) | ||

| Control Overweight (n= 11) | 85.45 (24.34) | 79.09 (28.18) | * | |

| Role Physical | ||||

| CFS Overweight (n= 13) | 25.00 (27.00) | 34.62 (36.14) | ||

| Control Overweight (n= 11) | 61.36 (45.23) | 75.00 (33.54) | * | |

| Bodily Pain | ||||

| CFS Overweight (n= 13) | 45.31 (19.18) | 48.38 (23.18) | ||

| Control Overweight (n= 11) | 76.00 (25.08) | 73.00 (23.63) | * | |

| General Health | ||||

| CFS Overweight (n= 11) | 54.00 (23.77) | 47.45 (19.81) | ||

| Control Overweight (n= 11) | 76.00 (19.99) | 77.18 (12.79) | * | |

| Vitality | ||||

| CFS Overweight (n= 13) | 27.31 (16.91) | 31.80 (18.60) | ||

| Control Overweight (n= 11) | 63.64 (19.63) | 53.64 (18.59) | ** | |

| Social Functioning | ||||

| CFS Overweight (n= 13) | 50.00 (19.76) | 58.65 (29.92) | ||

| Control Overweight (n= 11) | 87.50 (17.68) | 80.68 (24.60) | ** | |

| Role Emotional | ||||

| CFS Overweight (n= 13) | 48.72 (48.33) | 48.72 (46.38) | ||

| Control Overweight (n= 11) | 72.73 (38.92) | 72.73 (35.96) | ||

| Mental Health | ||||

| CFS Overweight (n= 12) | 61.00 (21.24) | 60.00 (22.11) | ||

| Control Overweight (n= 11) | 80.73 (20.85) | 76.36 (16.92) | * | |

| Krupp FSS | ||||

| CFS Overweight (n= 12) | 5.10 (1.98) | 5.22 (1.51) | ||

| Control Overweight (n= 7) | 3.56 (1.69) | 3.56 (1.31) | * | |

p< .05 = *

p< .001= **

We also found that the overweight/obese CFS group, when compared to overweight controls, was significantly more fatigued and more impaired on a number of SF-36 disability health outcomes. Our overweight/obese CFS group reported significantly more impairment in Physical Functioning, F (1, 22) = 4.63, p = .05; Role Physical, F (1, 22) = 10.31, p < .001; Bodily Pain, F (1, 22) = 11.82, p < .001; General Health, F (1, 20) = 11.65, p < .001; Vitality, F (1, 22) = 24.95, p < .001; Social Functioning, F (1, 22) = 15.69, p < .001; and Mental Health. F (1, 21) = 6.47, p = .02. However, Role-Emotional was not significantly different between these groups, F (1, 22) = 3.42, p = .08. Additionally Fatigue Severity Scale scores revealed the CFS sample (M = 5.16, SD = .42) reported a higher level of fatigue compared to the control group (M = 3.56, SD = .54), F (1, 17) = 5.53, p = .03.

Discussion

The present study sought to prospectively examine the impact of co-morbid weight issues on physical functioning and other health related symptoms among people with CFS. Initially, weight trends over time in a community based sample of individuals with CFS and healthy controls were examined. Weight trends were congruent with national trends, in that most people gain weight over time (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012). Additional longitudinal analyses revealed significant differences on a number of health and disability outcomes between overweight and obese individuals with CFS and similarly weighted controls. We observed substantial differences in disability and functioning health outcomes between overweight CFS and control groups. These results suggest that overweight and obese individuals with CFS have significantly worse physical and mental functioning, more severe fatigue, greater disability and are more symptomatic than controls who are similarly weighted. Interestingly, there was no significant main effect of group in the Role Emotional domain. This indicates that emotional functioning was comparable between controls and CFS groups, which in not compatible with the notion that individuals with CFS are primarily dealing with affective issues as suggested by Barsky and Borus (1999). The findings support the hypothesis that individuals diagnosed with CFS would demonstrate significantly more impairment than similarly weighted controls. Based on the present sample, these findings suggest that symptoms of CFS and the associated impairment in physical functioning cannot be explained solely by obesity.

Due to the debilitating nature of CFS, including impaired physical functioning and severe post-exertional malaise which may contribute to inactivity, and the growing evidence of impaired aerobic metabolism in this population, it is likely that patients with CFS often gain weight over time. Evidence of lower activity due to the illness is supported by Harvey, Wadsworth, Wessely, and Hotopf (2008) examined subject’s BMI index in a prospective study. Patients who went on to have CFS at age 53 had a statistically significant lower BMI than those who did not go on to develop CFS at ages 36 and 43 (before they had CFS). In more severe cases, CFS symptoms may become so devastating that patients are bedridden. There is a risk to excluding individuals from a CFS diagnosis due to BMI ≥ 40kg/m2. For example, in the present sample of 20 individuals diagnosed with CFS, one woman no longer met the Fukuda et al. (1994) criteria ten years later because she gained weight and her BMI increased to 40 kg/m2. If this diverse community-based sample is representative of the greater population, it is possible that 5% or more of individuals may lose their diagnosis as they gain weight over time. As an example, in a recent Great Britain study by Devasahayam, Lawn, Murphy, and White (2012), 5 patients were excluded from attending the service because of “pathological obesity”. As patients in that country are generally only allowed go to the local CFS service, these patients would be excluded from some services. It would be unfortunate if some patients are either denied clinical services due to weight gain, or denied disability insurance payment if diagnosed as overweight and not as having CFS.

The study has several limitations. Reliance on self-report of health outcomes may introduce subject bias. In addition, using BMI as a weight measure provides an indirect measure of obesity and does not reflect fat distribution. In future studies, it is suggested that a more accurate and reliable measure of percent body fat be used. BMI is a convenient and inexpensive estimate, but it does not distinguish between fat mass and lean tissue mass. The relevance of BMI as a true measure of body fat is controversial because cut-off points vary with race and gender, which seem arbitrary. Using a tape measure to measure waist circumference is more accurate and reliable than BMI, and is just as inexpensive. Other tests of body fatness such as the DEXA Scanning device which uses imaging technology, or a displacement test using a water or air tank have also been more reliable and accurate, but these tests are not as inexpensive as utilizing BMI or waist circumference calculations. Future studies should examine inactivity in CFS samples by longitudinally examining individuals who have a significant increase in BMI following diagnosis in order to further investigate whether obesity should be considered to be an exclusionary condition.

Certainly, Occupational Health Nurses will often be involved in developing and implementing treatment plans for such clients, such as those that feature a wholistic approach for restoring a sense of self-efficacy and control (Dyck, Allen, Barron, Marchi, Price, Spavor, & Tateishi, 1996) A key first step is assessing each patient’s unique condition and experience of CFS, and the condition of weight and changes over time need to be considered. Health care professionals might benefit from developing easy to use ways to measure fatigue and energy levels (Jason et al., 2008), and understanding the role of weight changes in such patients will enable health care workers to provide a better understanding of the unique challenges facing these patients, and ultimately in establishing treatment plans that are sensitive to their needs.

It is very possible that due to the illness, some patients with CFS gain weight over time. These patients may be forced to change their lifestyle. For example, a patient who lives alone might be too exhausted to cook. Some patients may choose convenience food, rather than cooking with vegetables and other healthy ingredients (which can involve a lot of chopping, etc.). Assistance by Occupational Health Nurses could be extremely helpful for helping patients find ways to cook and eat in a more healthy way. However, if most patients with CFS are considered to be more overweight or obese, it can lead to suggestions they brought it on themselves or are causing themselves not to get better. This however is not supported by Goedendorp, Knoop, Schippers, and Bleijenberg (2009), who found that patients with CFS were less overweight and led a healthier lifestyle than those in the general Dutch population. It is also important to note that some drugs such as antidepressants and those for pain can cause weight gain (Fulcher & White, 2000). However, it should be noted that people with CFS taking antidepressants aren’t necessarily specifically taking them for depression, as these drugs are often prescribed for the effects they have on other symptoms such as pain, sleep, IBS-type symptoms, etc.

In summary, chronic fatigue is a serious problem experienced by many patients, and these complaints are frequently dealt with by Occupational Health Nurses and other health care workers. Often clients with chronic fatigue are not well understood, and as a result, they might present unique challenges for health care workers. Those with a diagnosis of CFS are more impaired than those with chronic fatigue, and as such they are a high risk group needing clinical attention and care. By examining patients over time, as was done in the current study, it is possible to better understand some of the current controversies within the CFS area, such as possible weight gain. Finally, it is important to note that the idea of a weight cut-off was diagnosed for research purposes in mind, therefore if a patient had previously not had a BMI of over 40, but had satisfied the criteria, they shouldn’t necessarily be excluded from a clinical diagnosis if their weight increases over the arbitrary threshold.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the financial assistance provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant number AI055735).

References

- Afari N, Buchwald D. Chronic fatigue syndrome: A review. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:221–236. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsky AJ, Borus JF. Functional somatic syndromes. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999;130:910–921. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-11-199906010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalder T, Berelowitz G, Pawlikowska T, Watts L, Wessley S, Wright D, Wallace EP. Development of fatigue scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1993;37(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Becker P, Roeykens J, Reynders M, McGregor N, De Meirleir K. Exercise capacity in chronic fatigue syndrome. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(21):3270–3277. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demitrack MA, Dale JK, Straus SE, Laue L, Listwak SJ, Kruesi MJP, Chrousos GP, Gold PW. Evidence for impaired activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1991;73(6):1224–1234. doi: 10.1210/jcem-73-6-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devasahayam A, Lawn T, Murphy M, White PD. Alternative diagnoses to chronic fatigue syndrome in referrals to a specialist service: service evaluation survey. JRSM Short Report. 2012;3(1):4. doi: 10.1258/shorts.2011.011127. Epub 2012 Jan 12. http://shortreports.rsmjournals.com/content/3/1/4.full.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck D, Allen S, Barron J, Marchi J, Price BA, Spavor L, Tateishi S. Management of chronic fatigue syndrome. Case study. AAOHN Journal. 1996;44:85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JT, Colditz GA, Coakley EH, Moseley G, Manson JE, Willett WC, Kawachi I. A prospective study of weight change and health-related quality of life in women. Journal of American Medical Association. 1999;282(22):2136–2142. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.22.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Odgen CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among United States adults, 1999–2000. Journal of American Medical Association. 2002;288:1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A the International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. The chronic fatigue syndrome: A comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1994;121(12):953–959. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulcher KY, White PD. Strength and physiological response to exercise in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2000;69(3):302–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.3.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher D, Visser M, Sepulveda D, Pierson RN, Harris T, Heymsfield SB. How useful is body mass index for comparison of body fatness across age, sex, and ethnic groups? American Journal of Epidemiology. 1996;143(3):228–239. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedendorp MM, Knoop H, Schippers GM, Bleijenberg G. The lifestyle of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and the effect on fatigue and functional impairments. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2009;22(3):226–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2008.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among United States children, adolescents and adults, 1999–2002. Journal of American Medical Association. 2004;291:2847–2850. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Buchwald D, Wilks D, Sharpe M, Nix WA, Egle UT. Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2001;51:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SB, Wadsworth M, Wessely S, Hotopf M. Etiology of chronic fatigue syndrome: testing popular hypotheses using a national birth cohort study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(4):488–95. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816a8dbc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickie I, Davenport T, Wakefield D, Vollmer-Conna U, Cameron B, Vernon SD, Reeves WC, Lloyd A. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndrome precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: Prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2006;333(7568):575–578. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38933.585764.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Brown M, Evans M, Anderson V, Lerch A, Brown A, Hunnell J, Porter N. Measuring substantial reductions in functioning in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2011;33(7):589–598. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.503256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Melrose H, Lerman A, Burroughs V, Lewis K, King CP, Frankenberry EL. Managing chronic fatigue syndrome: Overview and case study. AAOHN Journal. 1999;47:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Muldowney K, Torres-Harding S. The energy envelope theory and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. AAOHN Journal. 2008;56:189–195. doi: 10.3928/08910162-20080501-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Porter N, Hunnell J, Rademaker A, Richman JA. CFS prevalence and risk factors over time. Journal of Health Psychology. 2011;16(3):445–456. doi: 10.1177/1359105310383603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Richman JA, Rademaker AW, Jordan KM, Plioplys AV, Taylor RR, McCready W, Huang CF, Plioplys S. A community-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159:2129–2137. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.18.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Wagner LI. Chronic fatigue syndrome among nurses. American Journal of Nursing. 1998;98:16B–16H. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Wagner L, Rosenthal S, Goodlatte J, Lipkin D, Papernik M, Plioplys S, Plioplys AV. Estimating the prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome among nurses. The American Journal of Medicine. 1998;105(3A):91S–93S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jammes Y, Steinberg JG, Mambrini O, Bregeon F, Delliaux S. Chronic fatigue syndrome: Assessment of increased oxidative stress and altered muscle excitability in response to incremental exercise. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2005;257(3):299–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Ropacki MT, Santoro NB, Richman JA, Heatherly W, Taylor R, Ferrari JR, Haney-Davis TM, Rademaker A, Dupuis J, Golding J, Plioplys AV, Plioplys S. A screening instrument for chronic fatigue syndrome: Reliability and validity. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 1997;31(1):39–59. doi: 10.1300/J092v03n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DA, McHorney C, Atkinson RL. Impact of obesity on health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illness. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:789–796. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.90906.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komaroff AL, Buchwald DS. Chronic fatigue syndrome: An update. Annual Review of Medicine. 1998;49:1–13. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komaroff AL, Fagioli LR, Doolittle TH, Gandek B, Gleit MA, Guerriero RT, Kornish RJ, Ware NC, Bates DW. Health status in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and in general population and disease comparison groups. The American Journal of Medicine. 1996;101(3):281–290. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(96)00174-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp LB, LaRocca G, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The Fatigue Severity Scale: Application to patients with Multiple Sclerosis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Archives of Neurology. 1989;46(10):1121–1123. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange G, DeLuca J, Maldjian JA, Lee HJ, Tiersky LA, Natelson BH. Brain MRI abnormalities exist in a subset of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1999;171:3–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim W, Thomas K, Bardwell W, Dimsdale J. Which measures of obesity are related to depressive symptoms and in whom? Psychosomatics. 2008;49(1):23–28. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.49.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher KJ, Klimas NG, Fletcher MA. Chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with diminished intracellular perforin. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2005;142:505–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCully KK, Natelson BH. Impaired oxygen delivery to muscle in chronic fatigue syndrome. Clinical Science. 1999;97:603–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care. 1993;31(3):247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natelson BH, Cohen JM, Brassloff I, Lee HJ. A controlled study of brain magnetic resonance imaging in patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1993;120:213–217. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(93)90276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in United States, 1999–2004. Journal of American Medical Association. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 82. 2012. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010; pp. 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among United States children and adolescents, 1999–2000. Journal of American Medical Association. 2002;288:1728–1732. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves WC, Lloyd A, Vernon SD, Klimas N, Jason LA, Bleijenberg G, Evengard B, White PD, Nisenbaum R, Under ER the International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Identification of ambiguities in the 1994 chronic fatigue syndrome research case definition and recommendations for resolution. BMC Health Services Research. 2003;3(25) doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, Thomas RJ, Collazo-Clavell ML, Korinek J, Allison TG, Batsis JA, Sert-Kuniyoshi FH, Lopez-Jimenez F. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. International Journal of Obesity. 2008;32:959–966. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanNess JM, Snell CR, Stevens SR. Diminished cardiopulmonary capacity during post-exertional malaise. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 2007;14(2):77–85. doi: 10.1300/J092v14n02_07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- VanNess JM, Stevens SR, Bateman L, Stiles TL, Snell CR. Postexertional malaise in women with chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19(2):239–244. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen RCW, Kurk RM, Visser FC, Sluiter W, Scholte HR. Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome performed worse than controls in a controlled repeated exercise study despite a normal oxidative phosphorylation capacity. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2010;8(93) doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey: Manual and interpretation guide. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]