Abstract

Background:

Adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival for patients with resected pancreatic cancer. Elderly patients are under-represented in Phase III clinical trials, and as a consequence the efficacy of adjuvant therapy in older patients with pancreatic cancer is not clear. We aimed to assess the use and efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients with pancreatic cancer.

Methods:

We assessed a community cohort of 439 patients with a diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma who underwent operative resection in centres associated with the Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative.

Results:

The median age of the cohort was 67 years. Overall only 47% of all patients received adjuvant therapy. Patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy were predominantly younger, had later stage disease, more lymph node involvement and more evidence of perineural invasion than the group that did not receive adjuvant treatment. Overall, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with prolonged survival (median 22.1 vs 15.8 months; P<0.0001). Older patients (aged ⩾70) were less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy (51.5% vs 29.8% P<0.0001). Older patients had a particularly poor outcome when adjuvant therapy was not delivered (median survival=13.1 months; HR 1.89, 95% CI: 1.27–2.78, P=0.002).

Conclusion:

Patients aged ⩾70 are less likely to receive adjuvant therapy although it is associated with improved outcome. Increased use of adjuvant therapy in older individuals is encouraged as they constitute a large proportion of patients with pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy, elderly

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in Western societies, with a 5-year survival rate of <5% (Jemal et al, 2008). Operative resection remains the primary treatment modality and the only chance of cure (Yeo et al, 1997). Those who undergo resection still only have a median survival of 14–20 months and a 5-year survival rate of ∼10% with surgery alone and up to 25% with adjuvant chemotherapy (Neoptolemos et al, 2001). Patterns of disease recurrence and the rapid demise of a high proportion of patients with pancreatic cancer even after complete surgical resection suggests that occult metastatic disease is often present at the time of surgery (Barugola et al, 2007; Schnelldorfer et al, 2008). Thus, it is clear that loco-regional therapies alone are usually not curative and systemic therapies need to be considered in the majority of patients following resection.

In pancreatic cancer, chemotherapy appears to be most effective in the adjuvant setting. In 2001, ESPAC-1 compared 5-fluorouracil, a pyrimidine analogue-based agent, to observation following resection and showed that chemotherapy delayed time to recurrence by 5.9 months and also improved overall survival (19.7 vs 14.0 months; P=0.0005) (Neoptolemos et al, 2001, 2004). In addition, CONKO-001 independently showed that adjuvant Gemcitabine, a nucleoside analogue, improved a 5-year survival of 10% after surgery alone to 20–25% (Oettle et al, 2007). Adjuvant Gemcitabine, owing to its favourable toxicity profile, has become the standard of care for this disease (Neoptolemos et al, 2010).

Approximately 60% of patients with pancreatic cancer are aged 65 and over (National Cancer Institute, 2010); however, patients enrolled in ESPAC-1 and CONKO-001 had a younger median age of 60 and 61, respectively (Neoptolemos et al, 2004; Oettle et al, 2007). It is increasingly recognised that elderly patients are under-represented in cancer trials and that well-selected elderly patients can undergo aggressive surgery for pancreatic cancer (Hutchins et al, 1999; Lee et al, 2010). This is an important issue in an ageing population as cancer is still a major cause of death in this age group (Edwards et al, 2002). It remains unclear whether the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with pancreatic cancer is effective, and given that this question is unlikely to be examined in a clinical trial, we assessed the efficacy of adjuvant therapy in a large community cohort.

We show that patients with pancreatic cancer in the community are older than patients included in Phase III clinical trials, and that elderly patients are less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy; yet it is well-tolerated and associated with improved outcome. This highlights the need for greater efforts to offer older patients adjuvant therapy and include them in clinical trials.

Patients and methods

Patients and data acquisition

Clinico-pathologic, treatment and outcome data for a cohort of 439 patients with a diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma who underwent pancreatic resection with curative intent (no macroscopic residual disease) were accrued from 12 hospitals associated with the Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative between 1990 to 2011 (APGI; www.pancreaticcancer.net.au) (Table 1). Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at each participating institution.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of entire cohort and dichotomized by age groups with univariate analysis.

| |

Entire cohort (N=439) |

Young cohort aged <70 years (n=261) |

Elderly cohort aged ⩾70 years (n=178) |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n (%) | Median OS (months) | P-value (log-rank) | n (%) | Median OS (months) | P-value (log-rank) | n (%) | Median OS (months) | P-value (log-rank) | P-valuea |

|

Mean age, years |

65.9 |

|

|

59.57 |

|

|

75.2 |

|

|

0.085 |

| Median |

67 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Range |

28–87 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.006 |

| Male |

230 (52.4) |

18.5 |

0.795 |

151 (57.9) |

19.6 |

0.470 |

79 (44.4) |

16.5 |

0.431 |

|

| Female |

209 (47.6) |

17.8 |

|

110 (42.1) |

22.1 |

|

99 (55.6) |

15.6 |

|

|

|

Stage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.008 |

| 1A |

10 (2.3) |

25.7 |

0.139 |

7 (2.7) |

24.8 |

0.884 |

3 (1.7) |

40.5 |

0.037 |

|

| 1B |

21 (4.9) |

|

|

18 (7.0) |

|

|

3 (1.7) |

|

|

|

| 2A |

114 (26.4) |

17.6 |

|

55 (21.4) |

19.6 |

|

59 (33.7) |

15.7 |

|

|

| 2B |

287 (66.4) |

|

|

177 (68.9) |

|

|

110 (62.9) |

|

|

|

|

Differentiation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.457 |

| Well |

33 (8.9) |

26.2 |

0.373 |

16 (7.4) |

26.2 |

0.576 |

17 (10.9) |

21.8 |

0.425 |

|

| Moderate |

238 (63.8) |

17.5 |

|

139 (64.1) |

20.2 |

|

99 (63.5) |

13.3 |

|

|

| Poor |

102 (27.3) |

18.1 |

|

62 (28.6) |

19.6 |

|

40 (25.6) |

16.0 |

|

|

|

Tumour location |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.299 |

| Head |

369 (86.0) |

18.5 |

0.021 |

223 (87.5) |

21.3 |

0.642 |

146 (83.9) |

16.9 |

0.005 |

|

| Body/tail |

60 (14.0) |

12.8 |

|

32 (12.5) |

19.3 |

|

28 (16.1) |

8.9 |

|

|

|

Tumour size (mm) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.827 |

| ⩽20 |

103 (23.6) |

25.0 |

0.001 |

62 (23.9) |

27.5 |

0.049 |

41 (23.0) |

24.4 |

0.005 |

|

| >20 |

334 (76.4) |

16.6 |

|

197 (76.1) |

19.4 |

|

137 (77.0) |

12.8 |

|

|

|

Margins (0 mm) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.345 |

| Clear |

272 (62.0) |

22.1 |

<0.0001 |

157 (60.2) |

23.4 |

<0.0001 |

115 (64.6) |

18.0 |

<0.0001 |

|

| Involved |

167 (38.0) |

13.5 |

|

104 (39.8) |

16.0 |

|

63 (35.4) |

11.0 |

|

|

|

Lymph nodes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.121 |

| Negative |

144 (33.3) |

19.7 |

0.025 |

78 (30.4) |

21.5 |

0.082 |

66 (37.5) |

18.0 |

0.122 |

|

| Positive |

289 (66.7) |

17.2 |

|

179 (69.6) |

19.3 |

|

110 (62.5) |

13.1 |

|

|

|

Perineural invasion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.280 |

| Negative |

102 (23.6) |

25.4 |

0.010 |

56 (21.8) |

27.5 |

0.113 |

46 (26.3) |

20.9 |

0.022 |

|

| Positive |

330 (76.4) |

17.2 |

|

201 (78.2) |

19.5 |

|

129 (73.7) |

13.3 |

|

|

|

Vascular invasion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.012 |

| Negative |

224 (52.1) |

20.5 |

0.017 |

120 (47.1) |

20.5 |

0.845 |

104 (59.4) |

19.3 |

<0.0001 |

|

| Positive |

206 (47.9) |

16.4 |

|

135 (52.9) |

21.5 |

|

71 (40.6) |

12.0 |

|

|

|

Radiotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.040 |

| No adjuvant |

416 (95.2) |

18.1 |

0.752 |

243 (93.5) |

19.7 |

0.830 |

173 (97.7) |

15.9 |

0.452 |

|

| Adjuvant |

21 (4.8) |

18.6 |

|

17 (6.5) |

21.5 |

|

4 (2.3) |

10.7 |

|

|

|

Adjuvant chemotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<0.0001 |

| Adjuvant |

187 (42.7) |

22.1 |

<0.0001 |

134 (51.5) |

22.5 |

0.085 |

53 (29.8) |

21.8 |

0.003 |

|

| No adjuvant |

251 (57.3) |

15.8 |

|

126 (48.5) |

17.5 |

|

125 (70.2) |

13.1 |

|

|

|

Palliative chemotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.002 |

| No palliative therapy |

314 (71.7) |

16.5 |

0.74 |

188 (67.9) |

18.5 |

0.266 |

126 (78.3) |

13.3 |

0.582 |

|

| Palliative therapy |

124 (28.3) |

21.3 |

|

89 (32.1) |

21.5 |

|

35 (21.7) |

21.1 |

|

|

|

Outcome |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pancreatic cancer death |

318 (72.4) |

|

|

182 (69.7) |

|

|

136 (76.4) |

|

|

0.124 |

| Death – other causes |

29 (6.6) |

|

|

16 (6.1) |

|

|

13 (7.3) |

|

|

|

| Alive |

92 (21.0) |

|

|

63 (24.1) |

|

|

29 (16.3) |

|

|

|

| Median overall survival (months) | 18.1 | 20.2 | 15.8 | 0.085 | ||||||

Abbreviation: OS=overall survival.

Comparison of variables between <70 cohort and ⩾70 cohort.

All cases underwent central pathology review by at least one specialist pancreatic histopathologist (AJG, AC, JGK) who was blinded to the diagnosis and clinical outcomes to verify the diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and to define histopathologic features in a standardized manner using a synoptic report developed for the purpose (Gill et al, 2009). Tumours were staged according to the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 7th edition 2009 (Edge and Compton, 2010).

Clinico-pathologic information was acquired initially retrospectively, and became prospective in 2006. Data were extracted from hospital notes (clinical history, preoperative imaging reports such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound and endoscopic ultrasonography, surgeon's operating reports, anaesthesiologists reports and correspondence letters from surgeon's and medical oncologist's consulting rooms). The date and cause of death were obtained from Cancer Registries and treating clinicians.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival was used as the primary end point and was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last clinical follow-up. Univariate Kaplan–Meier analysis of patient, tumour and treatment variables compared median survival using the log-rank test. Variables assessed were sex, age, tumour location, tumour size, lymph node status, stage, differentiation, vascular invasion, perineural invasion, margin status, treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy, palliative chemotherapy and adjuvant radiotherapy. Factors associated with differential survival on univariate analysis with a P-value <0.25, or with a previously published association were included in Cox proportional hazard multivariate analysis. Variables with a P-value<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to compare categorical variables and the Student's t-test to compare continuous variables for all analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 9.2 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient cohort (all patients)

The cohort of 439 patients consisted of 230 males and 209 females. The mean age at diagnosis was 65.9, with a median of 67 (range 28 to 87). Ninety-one patients (20.7%) were alive at the censor date of 30 September 2011. Three hundred and eighteen patients (72.5%) died of pancreatic cancer and 29 (6.6%) died of other causes. Twelve patients (2.8%) died within 30 days of surgery and 1 (0.2%) was lost to follow-up. Among those who were still alive, the median follow-up was 22.3 months (range, 0.5–193 months). The median progression-free survival was 12.8 months and the overall survival was 18.1 months.

Detailed clinico-pathologic, treatment and outcome characteristics of the cohort are presented in Table 1: 272 patients (62.0%) had resections with clear margins defined as no tumour present at transected surfaces (Chang et al, 2009)) and 289 (66.7%) had lymph node metastasis. The majority (86.0%) had tumours of the pancreatic head. Factors associated with improved outcome on univariate analysis included tumours of the pancreatic head (median survival 18.5 vs 12.8 months; P=0.0008) compared with body/tail tumours; tumour size >20 mm (25.0 vs 16.6 months; P=0.0008); absence of margin involvement (22.1 vs 13.5 months; P<0.0001); absence of lymph node metastases (19.7 vs 17.2 months; P=0.025); absence of perineural invasion (25.4 vs 17.2 months; P=0.01); absence of vascular space invasion (20.5 vs 16.4 months; P=0.017) and use of adjuvant chemotherapy (22.1 vs 15.8 months; P<0.0001; Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in survival between young patients (age <70; n=261) and older patients (defined as patients aged 70 or over; n=178) overall (median survival: 20.2 vs 15.8 months; P=0.085). Multivariate analysis identified that age, tumour size, margin status, perineural invasion, vascular space invasion and use of adjuvant chemotherapy were independent prognostic factors (Table 3A). The baseline characteristics of our cohort, excluding age, were comparable to Phase III trials in resected pancreatic cancer (Neoptolemos et al, 2004; Oettle et al, 2007).

Table 2. Comparison between adjuvant chemotherapy group and no adjuvant chemotherapy group in each cohort.

|

Entire cohort (N=439) |

Cohort aged <70 years (n=261) |

Cohort aged ⩾70 years (n=178) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Adjuvant chemotherapy (n=187) |

No adjuvant chemotherapy (n=251) |

|

Adjuvant chemotherapy (n=134) |

No adjuvant chemotherapy (n=126) |

|

Adjuvant chemotherapy (n=53) |

No adjuvant chemotherapy (n=125) |

|

| Variables | n (%) | n (%) | P-valuea | n (%) | n (%) | P-valuea | n (%) | n (%) | P-valuea |

| Mean age, years |

63.4 |

67.8 |

<0.0001 |

59.22 |

59.88 |

0.504 |

73.87 |

75.77 |

<0.001 |

|

Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 107 (57.2) | 122 (48.6) | 0.08 | 79 (59.0) | 71 (56.4) | 0.671 | 28 (52.8) | 51 (40.8) | 0.140 |

| Female |

80 (42.8) |

129 (51.4) |

|

55 (41.0) |

55 (43.7) |

|

25 (47.2) |

74 (59.2) |

|

|

Stage | |||||||||

| 1A | 1 (0.5) | 9 (3.7) | 0.04 | 1 (0.8) | 6 (4.8) | 0.013 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.5) | 0.013 |

| 1B | 7 (3.8) | 14 (5.7) | 4 (3.0) | 14 (11.3) | 3 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 2A | 41 (22.2) | 73 (29.7) | 28 (21.1) | 27 (21.8) | 13 (24.5) | 46 (37.7) | |||

| 2B |

136 (73.5) |

150 (61.0) |

|

99 (74.4) |

77 (62.1) |

|

37 (69.8) |

73 (59.8) |

|

|

Differentiation | |||||||||

| Well | 10 (7.2) | 23 (9.8) | 0.72 | 6 (6.0) | 10 (8.6) | 0.738 | 4 (10.3) | 13 (11.1) | 0.888 |

| Moderate | 90 (64.7) | 148 (63.2) | 64 (64.0) | 75 (64.1) | 26 (66.7) | 73 (62.4) | |||

| Poor |

39 (28.1) |

63 (26.9) |

|

30 (30.0) |

32 (27.4) |

|

9 (23.1) |

31 (26.5) |

|

|

Tumour location | |||||||||

| Head | 159 (88.8) | 209 (83.9) | 0.16 | 116 (89.2) | 106 (85.5) | 0.368 | 43 (87.8) | 103 (82.4) | 0.387 |

| Body/tail |

20 (11.2) |

40 (16.1) |

|

14 (10.8) |

18 (14.5) |

|

6 (12.2) |

22 (17.6) |

|

|

Tumour size (mm) | |||||||||

| ⩽20 | 44 (23.7) | 59 (23.6) | 0.99 | 34 (25.6) | 28 (22.4) | 0.552 | 10 (18.9) | 31 (24.8) | 0.390 |

| >20 |

142 (76.3) |

191 (76.4) |

|

99 (74.4) |

97 (77.6) |

|

43 (81.1) |

94 (75.2) |

|

|

Margins (0 mm) | |||||||||

| Clear | 112 (59.9) | 159 (63.3) | 0.49 | 79 (59.0) | 77 (61.1) | 0.723 | 33 (62.3) | 82 (65.6) | 0.670 |

| Involved |

75 (40.1) |

92 (36.7) |

|

55 (41.0) |

49 (38.9) |

|

20 (37.7) |

43 (34.4) |

|

|

Lymph nodes | |||||||||

| Negative | 49 (26.3) | 95 (38.6) | 0.008 | 33 (24.8) | 45 (36.6) | 0.041 | 16 (30.2) | 50 (40.7) | 0.188 |

| Positive |

137 (73.7) |

151 (61.3) |

|

100 (75.2) |

78 (63.4) |

|

37 (69.8) |

73 (59.4) |

|

|

Perineural invasion | |||||||||

| Negative | 32 (17.4) | 70 (28.3) | 0.008 | 21 (15.9) | 35 (28.2) | 0.017 | 11 (21.2) | 35 (28.5) | 0.316 |

| Positive |

152 (83.5) |

177 (71.7) |

|

111 (84.1) |

89 (71.8) |

|

41 (78.9) |

88 (71.5) |

|

|

Vascular invasion | |||||||||

| Negative | 88 (47.8) | 136 (55.5) | 0.12 | 57 (43.2) | 63 (51.6) | 0.177 | 31 (59.6) | 73 (59.4) | 0.974 |

| Positive |

96 (52.2) |

109 (44.4) |

|

75 (56.8) |

59 (48.4) |

|

21 (40.4) |

50 (40.7) |

|

|

Palliative chemotherapy | |||||||||

| No palliative | 137 (73.3) | 177 (70.5) | 0.528 | 91 (67.9) | 81 (64.3) | 0.537 | 46 (86.8) | 96 (76.8) | 0.129 |

| Palliative |

50 (26.7) |

74 (29.5) |

|

43 (32.1) |

45 (35.7) |

|

7 (13.2) |

29 (23.2) |

|

|

Radiotherapy | |||||||||

| No adjuvant | 169 (90.9) | 247 (98.4) | <0.00001 | 119 (88.8) | 124 (98.4) | 0.022 | 50 (96.2) | 123 (98.4) | 0.012 |

| Adjuvant |

17 (9.1) |

4 (1.6) |

|

15 (11.2) |

2 (1.6) |

|

2 (3.9) |

2 (1.6) |

|

|

Outcome | |||||||||

| Pancreatic cancer death | 112 (59.8) | 206 (82.1) | <0.0001 | 83 (61.9) | 99 (78.6) | 0.003 | 29 (54.7) | 107 (85.6) | <0.0001 |

| Death – other causes | 8 (4.3) | 21 (8.4) | 5 (3.7) | 11 (8.7) | 3 (5.7) | 10 (8.0) | |||

| Alive |

67 (35.8) |

24 (9.6) |

|

46 (34.3) |

16 (12.7) |

|

21 (39.6) |

8 (6.4) |

|

| Median overall survival (months) | 22.1 | 15.8 | <0.0001 | 22.5 | 17.5 | 0.085 | 21.8 | 13.1 | 0.003 |

Comparison of variables between adjuvant chemotherapy and no adjuvant chemotherapy within each cohort.

Table 3. Final multivariate model of overall survival for entire cohort, elderly cohort and young patient cohort.

| Variables | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

|

(A) Entire cohort | ||

| Age, ⩾70 years | 1.35 (1.07–1.70) | 0.01 |

| Tumour size, >20 mm | 1.43 (1.10–1.85) | 0.007 |

| Margins, involved | 1.69 (1.35–2.12) | <0.0001 |

| Perineural invasion, positive | 1.33 (1.02–1.72) | 0.033 |

| Vascular invasion, positive | 1.37 (1.09–1.71) | 0.007 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, none |

1.38 (1.21–1.50) |

<0.0001 |

|

(B) Older cohort (age ⩾70 years) | ||

| Tumour location, head | 1.37 (1.03–1.59) | 0.037 |

| Margins, involved | 1.98 (1.40–2.79) | <0.0001 |

| Vascular invasion, positive | 2.79 (1.60–3.24) | <0.0001 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, none |

1.47 (1.21–1.64) |

0.002 |

|

(C) Young cohort (age <70 years) | ||

| Margins, involved | 1.81 (1.36–2.42) | <0.0001 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, none | 1.35 (1.02–1.79) | 0.035 |

Abbreviation: CI=confidence interval.

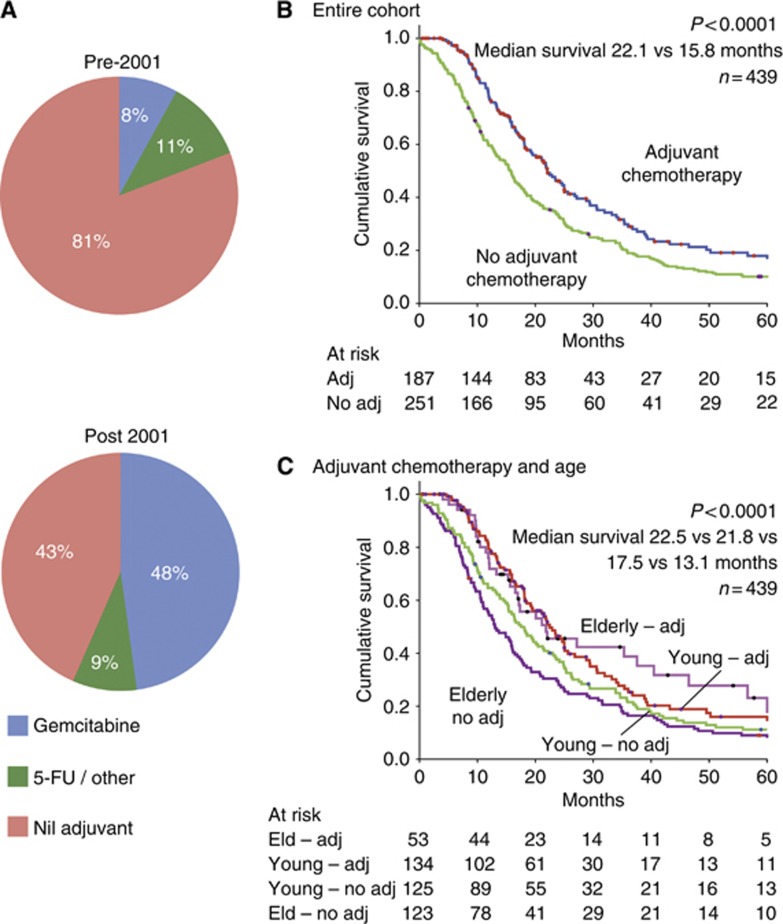

A total of 205 patients (46.7%) received adjuvant therapy: 187 patients (42.7%) received adjuvant chemotherapy, whereas 21 (4.8%) received adjuvant radiotherapy and 32 (7.3%) received chemoradiation. The majority of patients who received chemotherapy received Gemcitabine (n=145; 79.2%) and the remainder received 5-Flourouracil and/or platinum-based cytotoxics. The mean number of cycles received was 5. Use of chemotherapy increased significantly after 2001 when clinical trial data began to emerge supporting its use. Pre-2001, only 19.1% of patients received adjuvant chemotherapy compared with 56.5% after 2001 (P<0.0001). In addition, the use of Gemcitabine increased post 2001 (8.0% vs 47.8% P<0.0001) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Use of adjuvant chemotherapy before and after publication of ESPAC-1 in 2001. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of the entire cohort stratified by use of adjuvant chemotherapy (N=439). (C) Kaplan–Meier survival curves of sub-groups (<70 and ⩾70) stratified by use of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Patients that receive adjuvant chemotherapy have poor prognostic factors

To further clarify the role of adjuvant chemotherapy, patients were stratified into two groups of ‘adjuvant chemotherapy' and ‘no adjuvant chemotherapy'. Patient, tumour and treatment characteristics of the two groups were compared (Table 2). The group that received adjuvant chemotherapy had more poor prognostic factors including more advanced stage (stage 2B; 73.5% vs 61.0% P=0.04), more tumours with positive lymph nodes (73.7% vs 61.3% P=0.008) and a higher prevalence of perineural invasion (83.5% vs 71.7% P=0.008). In addition, the group that had adjuvant chemotherapy was significantly younger (63.4 vs 67.8 years; P <0.0001). Despite the constellation of adverse features, the group that received adjuvant chemotherapy had a significantly better median survival (Figure 1B).

Older patients that do not receive adjuvant therapy have a poor prognosis

To investigate the relationship between age and outcome, patients were stratified into two groups of ‘cohort younger than 70' and ‘cohort 70 or older'. Sex, tumour pathological characteristics and treatment (adjuvant chemotherapy, palliative chemotherapy and radiotherapy) were compared between the two groups. A total of 178 patients (40.5%) were ⩾70 years old. The younger cohort (<70) had more poor prognostic factors; more males (57.9% vs 44.4% P=0.006), more advanced stage (stage 2B; 68.1% vs 62.9% P=0.008) and more patients with evidence of vascular space invasion (52.1% vs 40.6% P=0.012). Adjuvant chemotherapy (51.5% vs 29.8% P<0.0001), palliative chemotherapy (33.8% vs 20.2% P=0.002) and adjuvant chemoradiation (10.0% vs 3.4% P=0.009) were all less frequently administered in the older (⩾70) patient subgroup (Table 1). The 30-day mortality did not differ (1.9% vs 4.0% P=0.187) and the mean number of cycles of chemotherapy received was the same in the two sub-groups (5.2 vs 5.2; P=0.922). The cause of death in patients aged ⩾70 was predominantly pancreatic cancer (76.4%) and did not significantly differ from young patients. Only 7.3% of pancreatic cancer patients aged ⩾70 died of causes other than cancer, again no different to younger patients (7.3% vs 6.1% P=0.124).

Not receiving adjuvant chemotherapy was an independent poor prognostic factor in the older population (HR 1.89, 95% CI: 1.27–2.78, P=0.002) (Table 3B). Figure 1C shows the cohort divided into four groups based on age (<70 and ⩾70) and use of adjuvant chemotherapy (adj and no adj). Patients aged ⩾70 who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy had an extremely poor outcome with a median survival of only 13.1 months despite favourable clinico-pathologic features, whereas elderly patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy had an outcome similar to young patients (21.8 vs 22.5; P=0.576) (Table 2; Figure 1C). In addition, patients aged ⩾70 who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy were less likely to receive palliative chemotherapy than the corresponding group of patients aged <70 (23.2% vs 35.7% P=0.03); however, palliative chemotherapy had no effect on survival in either group on univariate or multivariate analysis.

Discussion

Adjuvant chemotherapy improves outcomes for patients with pancreatic cancer in the community and supports clinical trial data even though clinical trials selectively recruit patients (Neoptolemos et al, 2004; Oettle et al, 2007). Patients in the community are older than patients in clinical trials, and older patients are less likely to receive adjuvant therapy, although data from this study suggest that it is associated with improved survival to a similar, if not greater degree as it is for younger patients.

Recently, several studies have examined the role of palliative chemotherapy in advanced pancreatic cancer showing that Gemcitabine in elderly patients is as well-tolerated and equally as effective as in younger patients (Marechal et al, 2008; Hentic et al, 2011). With regard to adjuvant therapy, a recent population study suggested that adjuvant chemotherapy was less frequently administered to older patients with pancreatic cancer (Davila et al, 2009). Previous studies focusing on colon and breast cancer as well as a single institution study in pancreatic cancer suggest that older patients are less likely to receive adjuvant treatment in many different cancer types, although it is associated with improved outcomes (Potosky et al, 2002; Bouchardy et al, 2003; Barbas et al, 2012).

In older patients with cancer, reluctance to administer adjuvant treatment may be based on the perception that they have an increased risk of a non-cancer-related cause of death and therefore the overall benefit of adjuvant therapy is limited. Our study highlights that this is not the case and the predominant cause of death in older patients is still cancer, and not different to a younger population. The mean number of cycles of chemotherapy received by elderly patients was the same as young patients suggesting that once adjuvant treatment was commenced, older patients were equally likely to complete treatment. Importantly, adjuvant chemotherapy is the only actionable variable associated with improved survival in older patients. Unless further studies emerge suggesting that adjuvant chemotherapy provides unacceptable toxicity in the elderly, efforts to increase the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients may improve overall outcomes, particularly in the setting of ageing populations.

We acknowledge that there are limitations to this study and that a prospective study in older patients would better clarify the role of adjuvant chemotherapy. Such a study may be difficult to conduct given the proven role of adjuvant chemotherapy and unlikely to be undertaken. As the study did not collect preferences data, it is not possible to comment on the reasons that patients did not receive adjuvant treatments. In addition, we cannot be certain that older patients were not more likely to be of a lower performance status following surgery. However, the study found that the post-operative stay following surgery was similar (12 days) as was the post-operative mortality rate. In addition, the rates of adjuvant chemotherapy use have increased since 2001 suggesting that an increase in uptake is possible and may be independent of patient characteristics.

In conclusion, pancreatic cancer is predominantly a cancer of older age groups and therefore is not entirely reflective of patients who were included in published Phase 3 clinical trials. In this study, adjuvant chemotherapy was independently associated with improved outcome in all patients. The benefit of 8.7 months with adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients is clinically significant; however, the utilisation rate of adjuvant treatments is markedly lower than in young patients despite similar clinico-pathologic features. Moreover, older patients who did receive adjuvant chemotherapy were equally likely to complete treatment. Advancing age alone should not preclude the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in this highly lethal disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members and administrative staff of the NSW Pancreatic Cancer Network and the Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative. For full list of members, please see www.pancreaticcancer.net.au. The funding bodies had no role in the design or conduct of the study. This research was supported by The National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia, The Cancer Council NSW, Cancer Institute NSW, Sydney Catalyst, Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, Royal Australasian College of Physicians, St Vincent's Clinic Foundation, RT Hall Trust, Jane Hemstritch for Phillip Hemstritch and the Avner Nahmani Pancreatic Cancer Foundation.

References

- Barbas AS, Turley RS, Ceppa EP, reddy SK, blazer DG, 3RD, Clary BM, Pappas TN, Tyler DS, White RR, Lagoo SA. Comparison of outcomes and the use of multimodality therapy in young and elderly people undergoing surgical resection of pancreatic cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:344–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barugola G, Falconi M, Bettini R, Boninsegna L, Casarotto A, Salvia R, Bassi C, Pederzoli P. The determinant factors of recurrence following resection for ductal pancreatic cancer. JOP. 2007;8:132–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Fioretta G, Laissue P, Neyroud-Caspar I, Schafer P, Kurtz J, Sappino AP, Vlastos G. Undertreatment strongly decreases prognosis of breast cancer in elderly women. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3580–3587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang DK, Johns AL, Merrett ND, Gill AJ, Colvin EK, Scarlett CJ, Nguyen NQ, Leong RW, Cosman PH, Kelly MI, Sutherland RL, Henshall SM, Kench JG, Biankin AV. Margin clearance and outcome in resected pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2855–2862. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila JA, Chiao EY, Hasche JC, Petersen NJ, Mcglynn KA, Shaib YH. Utilization and determinants of adjuvant therapy among older patients who receive curative surgery for pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2009;38:e18–e25. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318187eb3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards BK, Howe HL, Ries LA, Thun MJ, Rosenberg HM, Yancik R, Wingo PA, Jemal A, Feigal EG. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973-1999, featuring implications of age and aging on U.S. cancer burden. Cancer. 2002;94:2766–2792. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill AJ, Johns AL, Eckstein R, Samra JS, Kaufman A, Chang DK, Merrett ND, Cosman PH, Smith RC, Biankin AV, Kench JG. Synoptic reporting improves histopathological assessment of pancreatic resection specimens. Pathology. 2009;41:161–167. doi: 10.1080/00313020802337329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentic O, Dreyer C, Rebours V, Zappa M, Levy P, Raymond E, Ruszniewski P, Hammel P. Gemcitabine in elderly patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3497–3502. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i30.3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Jr, Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:2061–2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MK, Dinorcia J, Reavey PL, Holden MM, Genkinger JM, Lee JA, Schrope BA, Chabot JA, Allendorf JD. Pancreaticoduodenectomy can be performed safely in patients aged 80 years and older. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1838–1846. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marechal R, Demols A, Gay F, De Maertelaer V, Arvanitaki M, Hendlisz A, Van Laethem JL. Tolerance and efficacy of gemcitabine and gemcitabine-based regimens in elderly patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2008;36:e16–e21. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31815f3920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute, D 2010. Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) Research Data (1973-2007). Released April 2010, based on the November 2009 submission edn.

- Neoptolemos JP, Dunn JA, Stocken DD, Almond J, Link K, Beger H, Bassi C, Falconi M, Pederzoli P, Dervenis C, Fernandez-Cruz L, Lacaine F, Pap A, Spooner D, Kerr DJ, Friess H, Buchler MW. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:1576–1585. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, Ghaneh P, Cunningham D, Goldstein D, Padbury R, Moore MJ, Gallinger S, Mariette C, Wente MN, Izbicki JR, Friess H, Lerch MM, Dervenis C, Olah A, Butturini G, Doi R, Lind PA, Smith D, Valle JW, Palmer DH, Buckels JA, Thompson J, Mckay CJ, Rawcliffe CL, Buchler MW. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1073–1081. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, Bassi C, Dunn JA, Hickey H, Beger H, Fernandez-Cruz L, Dervenis C, Lacaine F, Falconi M, Pederzoli P, Pap A, Spooner D, Kerr DJ, Buchler MW. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1200–1210. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, Gellert K, Langrehr J, Ridwelski K, Schramm H, Fahlke J, Zuelke C, Burkart C, Gutberlet K, Kettner E, Schmalenberg H, Weigang-Koehler K, Bechstein WO, Niedergethmann M, Schmidt-Wolf I, Roll L, Doerken B, Riess H. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Kaplan RS, Johnson KA, Lynch CF. Age, sex, and racial differences in the use of standard adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1192–1202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnelldorfer T, Ware AL, Sarr MG, Smyrk TC, Zhang L, Qin R, Gullerud RE, Donohue JH, Nagorney DM, Farnell MB. Long-term survival after pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: is cure possible. Ann Surg. 2008;247:456–462. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181613142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, Hruban RH, Ord SE, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Zahurak ML, Grochow LB, Abrams RA.1997Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes Ann Surg 226248–257.. discussion 257-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]