Abstract

The androgen receptor (AR) has a vital role in the onset and progression of prostate cancer by promoting G1-S progression, possibly by functioning as a licensing factor for DNA replication. We here report that low dose 2-methoxyestradiol (2-ME), an endogenous estrogen metabolite, induces mitotic arrest in prostate cancer cells involving activation of the E3 ligase CHIP (C-terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein) and degradation of the AR. Depletion of the AR by small interfering RNA (siRNA) eliminates 2-ME-induced arrest and introducing AR into PC3-M cells confers 2-ME-induced mitotic arrest. Knockdown of CHIP or MDM2 (mouse homolog of double minute 2 protein) individually or in combination reduced AR degradation and abrogated M phase arrest induced by 2-ME. Our data link AR degradation via ubiquitination to mitotic arrest. Targeting the AR by activating E3 ligases such as CHIP represents a novel strategy for the treatment of prostate cancer.

Keywords: prostate cancer, androgen receptor, 2-methoxyestradiol, CHIP, mitotic arrest

INTRODUCTION

The androgen receptor (AR), a ligand-dependent transcription factor, has a pivotal role in the development and progression of prostate cancer, the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among the men in the United States.1 The AR acquires autonomous function and actively promotes cancer cell growth and proliferation, in part by promoting cell cycle progression.2 The natural history of prostate cancer is characterized by the propensity of the disease to progress from an early stage androgen-dependent state to an androgen-independent state.3 Although most patients with metastatic disease initially respond to androgen ablation, ultimately they develop androgen-independent metastases and succumb to their disease.4

Despite the fact that late stage prostate cancer is refractory to androgen withdrawal or antiandrogen therapy, signaling through the AR is thought to be crucial in disease progression. The AR itself is therefore a therapeutic target, since AR signaling remains important even in the face of androgen deprivation or blockade through mechanisms, including amplification or mutation of the AR, as well as through alterations in AR activators or coactivators.5–7 These molecular alterations allow AR signaling to remain active in response to low levels of adrenal androgen, other steroids and even antiandrogens as well as by ligand independent mechanisms.7 Furthermore, a correlation exists between androgen independence and the level of AR expression.8,9 The failure of current therapeutic strategies may be explained, at least in part, by the fact that the AR is expressed in essentially all human prostate cancers, even those that have become hormone refractory.8,9 As androgen-AR signaling is critical for prostate cancer cell proliferation and maintenance, decreasing AR levels in prostate cancer cells is an attractive therapeutic strategy for this deadly malignancy.

2-Methoxyestradiol (2-ME) is a naturally occurring estrogen metabolite, which interferes with microtubule function by inhibiting polymerization, and has been shown to exhibit both antitumor and antiangiogenic properties.10–15 2-ME causes growth inhibition and apoptosis in both androgen-independent (PC3-M and C4-2) and androgen-dependent (LNCaP) prostate cancer cell lines by arresting cells in M phase of the cell cycle.14,15 We have previously demonstrated that 2-ME effectively radiosensitizes PC3-M cells in vitro and in vivo by modulating p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase.16 As the AR is the key regulator of prostate cancer progression, we explored the role of the AR in 2-ME-induced cell cycle arrest.

Here, we show the AR-positive cell lines (LNCaP, C4-2 and 22RV1) are ten-fold more sensitive to 2-ME-induced M phase arrest than AR-negative PC3-M cells. The increased sensitivity of AR-positive cells to 2-ME treatment is due to degradation of the AR caused by 2-ME activation of the E3 ligase CHIP (C-terminus of Hsp70-interacting protein), as knockdown of either AR or CHIP makes AR-positive cells resistant to 2-ME-induced mitotic arrest. This finding establishes a novel link between AR degradation by CHIP and mitotic arrest.

RESULTS

Human prostate cancer cells arrest in G2/M phase in response to low doses of 2-ME

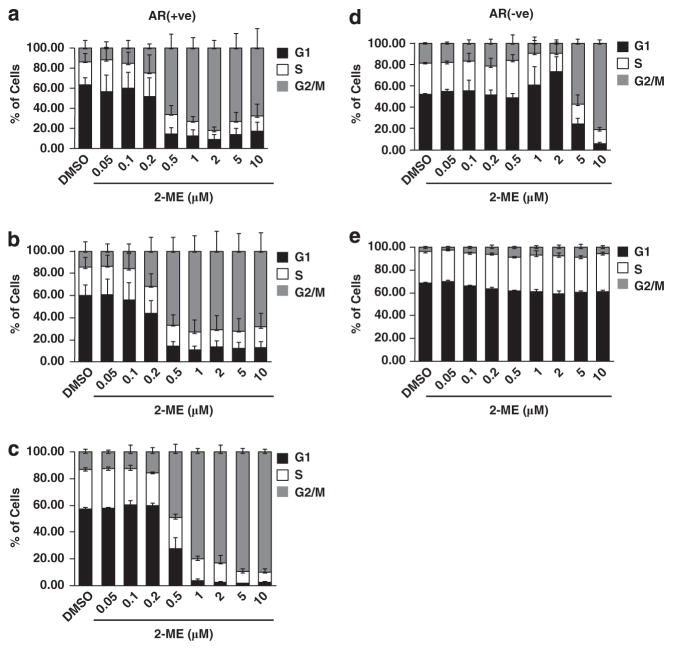

We treated AR-positive and AR-null prostate cancer cell lines with different concentrations of 2-ME for 24 h. In the AR-positive cell lines LNCaP (Figure 1a), C4-2 (Figure 1b) and 22Rv1 (Figure 1c and Supplementary Figure S1A) cells were arrested in G2/M phase (by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis) at and above a dose of 0.5 μM of 2-ME. In contrast, in the AR-null cell line PC3-M 2-ME had to be added up to 5 μM to elicit a response (Figure 1d). Notably, we did not observe any significant changes in G2/M phase population in RWPE1 (immortalized normal prostate epithelial cells) even at higher doses of 2-ME (Figure 1e and Supplementary Figure S1B). The fraction of cells in G1 and S phases decreased, corresponding to the increase in G2/M in all the four cell lines. The cells with 4 N DNA content by FACS were arrested in mitosis, as evident from increased phosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser10 (Supplementary Figure S2) However, at low doses of 2-ME (0.5 μM) proliferation of LNCaP (Supplementary Figure S3A) and C4-2 (Supplementary Figure S3B) cells were inhibited as early as day 1 and barely detectable by day 4, in contrast to PC3-M cells that continued to proliferate even at higher 2-ME concentrations (Supplementary Figure S3C).

Figure 1.

Effects of 2-ME on cell cycle status of LNCaP, C-42 and 22Rv1 cells. Cell cycle distribution of (a) LNCaP, (b) C4-2, (c) 22Rv1, (d) PC3-M and (e) RWPE1 cells treated with different concentrations of 2-ME. DNA content was measured by propidium iodide (PI) staining after 24 h and cell cycle stage determined by FACS using CellQuest software. Mean±s.d. of at least three independent experiments.

Involvement of p53 in the mitotic arrest

PC3-M cells lack p53, which might account for the striking difference in mitotic arrest and proliferation in response to 2-ME. p53 controls both G2/M and G1 cell cycle check points in human fibroblasts.17 Therefore, we examined the p53 status in 2-ME treated LNCaP and C4-2 cells. As shown in Supplementary Figure S4A and Supplementary Figure S4B, p53 levels increased in a 2-ME dose-dependent manner. To test whether p53 was involved in mitotic arrest induced by low concentrations of 2-ME, we silenced p53 by RNA interference (RNAi) in LNCaP and C4-2 cells, and observed no significant difference in the proportion of G2/M cells compared with control (Supplementary Figure S4C and Supplementary Figure S4D). The efficiency of p53 knockdown is shown in Supplementary Figure S4E, lane 2 and lane 6 for LNCaP and C4-2, respectively. These data led us to conclude that 2-ME-induced mitotic arrest in prostate cancer cells was not p53-dependent.

AR protein is decreased post-transcriptionally upon 2-ME treatment

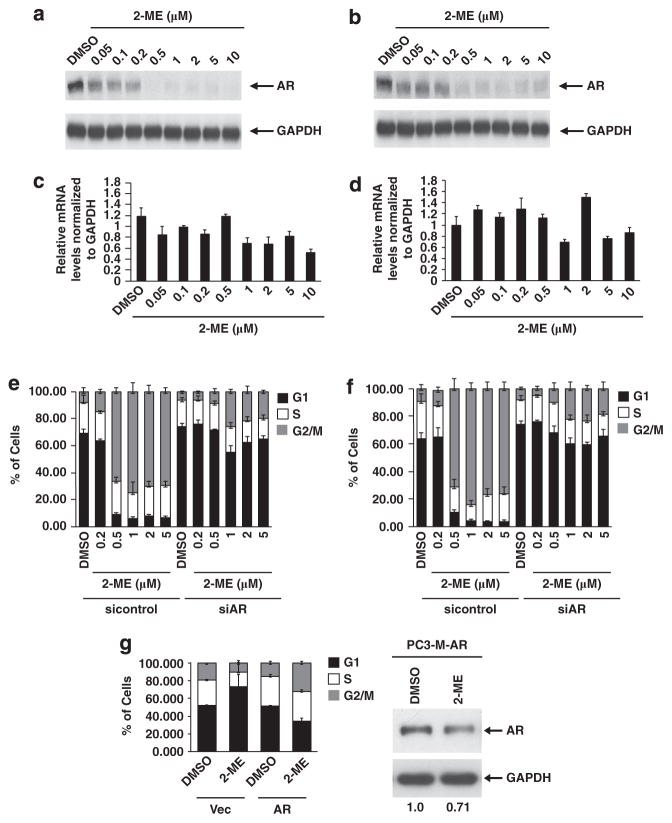

AR protein levels were significantly reduced in response to 2-ME in both LNCaP (Figure 2a) and C4-2 (Figure 2b) cells. Interestingly, quantitative reverse-transcription–PCR (qRT–PCR) revealed that AR mRNA levels were unchanged in 2-ME treated vs untreated controls in both LNCaP (Figure 2c) and C4-2 cells (Figure 2d). Ablation of AR protein relative to unchanged RNA suggests that post-transcriptional mechanisms were in play.

Figure 2.

2-ME down-regulates AR, required for G2/M phase arrest. (a,b) Western blot for AR and GAPDH (as loading control) in lysates from (a) LNCaP and (b) C4-2 cells treated for 24 h with the indicated concentrations of 2-ME. (c,d) qRT–PCR of mRNA at indicated concentrations of 2-ME in LNCaP (c) and C4-2 cells (d). AR mRNA levels were plotted after normalizing to that of GAPDH. FACS analysis of (e) LNCaP and (f) C4-2 cells depleted of AR by siRNA, compared with control siRNA treated cells (left half). Results are representative of at least three independent experiments. (g) PC3-M cells stably infected with either empty lentiviral vector or lentivirus expressing AR were treated without or with 2-ME for 24 h. FACS analysis of PC3-M stably expressing empty vector or WT-AR (left) and immunoblot for AR in PC3-M cells expressing AR (5 μg of protein, right), with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) serving as the loading control.

Silencing of AR abrogates mitotic arrest

Silencing of the AR using small interfering (siRNA) abrogated the G2/M arrest in response to 2-ME in both LNCaP (Figure 2e) and C4-2 cells (Figure 2f). AR protein levels were reduced in control siRNA cells upon 2-ME treatment (Supplementary Figures S5A and S5B). Similar results were observed when the AR was silenced by a second siRNA that targeted the 3′-UTR (untranslated region) of the AR gene (siAR-2), (Supplementary Figure S5C). On the other hand, stable expression of wild-type AR in PC3-M cells conferred sensitivity to 2-ME treatment, with more cells accumulating in G2/M, compared with control cells (Figure 2g). These data strongly suggest the AR is required for the response to 2-ME in these cell lines.

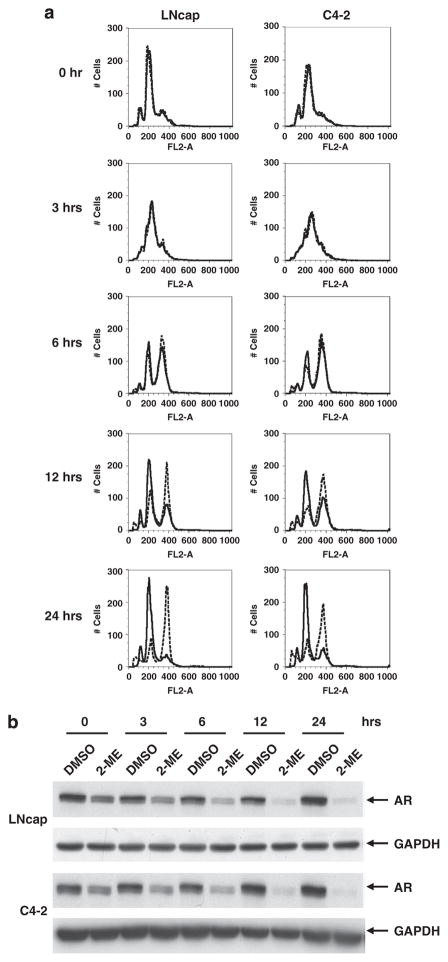

2-ME downregulates AR in S phase in both LNCaP and C4-2 cells To determine in which stage of the cell cycle AR was down-regulated, LNCaP and C4-2 cells were stalled at the G1/S transition by treatment for 24 h with aphidicholin, an inhibitor of the replicative DNA polymerase. Cells were then treated with or without 2-ME for an additional 24 h. The cells were arrested in G1/S phase (Figure 3a, 0 h), and AR protein was still down-regulated in response to 2-ME treatment (Figure 3b, 0 h, compare DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) and 2-ME treatment).

Figure 3.

2-ME down-regulates AR in G1/S phase of cell cycle. (a) LNCaP (left) or C4-2 (right) cells were held in G1/S by adding aphidicholin, and 24 h later cells were treated without (solid lines) or with (dotted lines) 2-ME (2 μM). After 24 h of 2-ME treatment, cells were released from the aphidicholin block without (solid lines) or with (dotted lines) 2-ME. Overlay of FACS analysis for DNA content at indicated time points after release from aphidicholin is shown. (b) Western blot analysis for AR shows AR protein is down-regulated in both LNCaP (upper panel) and C4-2 (lower panel) cells upon 2-ME treatment. GAPDH is shown as a loading control.

To further assess the importance of the AR in mitotic arrest by 2-ME, cells were washed and released from aphidicholin block in the presence or absence of 2-ME. Their progression through S phase and G2 was followed by FACS (Figure 3a). Although we did not observe any difference in S phase entry (3 h) between 2-ME-treated and untreated cells, a significant proportion of 2-ME-treated cells remained in G2/M phase (4 N DNA content) at later times (6, 12 and 24 h). In contrast, vehicle (DMSO)-treated cells entered into the next cell cycle. As expected, AR levels were downregulated in S phase by 2-ME, resulting in G2/M arrest.

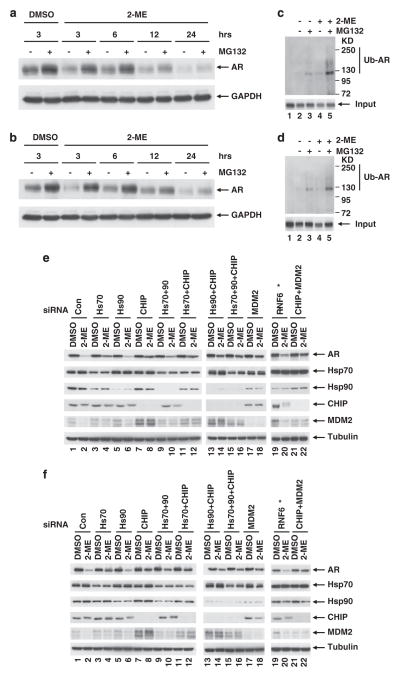

Proteasomal degradation of the AR is mediated by the E3 ubiquitin ligases, CHIP and MDM2 (mouse homolog of double minute 2 protein)

Our results revealed that AR protein ablation by 2-ME is post-transcriptional, so we asked whether this occurred via proteasomal degradation. We treated LNCaP (Figure 4a) and C4-2 (Figure 4b) cells with 2-ME in the presence or absence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Immunoblots showed that the AR was reduced within 3 h of 2-ME treatment, but this was prevented by MG132 for all time points up to 24 h. We checked AR ubiquitination after 2-ME treatment. As shown in Figures 4c and d 2-ME treatment increased the level of ubiquitinated AR and this was increased further by MG132 compared with controls in both LNCap and C4-2 respectively.

Figure 4.

AR degradation by ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway. (a) LNCaP or (b) C4-2 cells were treated with or without 2-ME (2 μM), and with or without proteasome inhibitor MG132 (5 μg/ml). Proteasome inhibitor MG132 was added 3 h before harvest at indicated time points. Cells were lysed and extracts were immunobloted for AR and GAPDH (as loading control). (c,d) Ubiquitinated proteins were isolated from extracts either with control beads (lane 1) or polyubiquitin-binding TUBEs (lane 2–5, see Materials and methods) and immunobloted for AR in LNCaP and C4-2 cells respectively. (e) LNCaP or (f) C4-2 cells were depleted of the indicated proteins with specific siRNA and treated with 2-ME (1 μM) for 24 h. Immunoblots for AR, Hsp70, Hsp90, CHIP and MDM2 are shown. Tubulin blots shown as loading controls. *Due to lack of availability of an effective antibody against RNF6, knockdown was monitored by qRT–PCR. mRNA levels are shown in Supplementary Figure S7.

Proteasomal degradation of the AR is known to be mediated by two well known E3 ligases: CHIP and MDM2. To determine the involvement of CHIP in 2-ME-induced AR degradation, various components of the heat shock protein (Hsp)–CHIP complex were silenced by siRNA (Figures 4e and f). The complex is composed of two Hsps, Hsp70 and Hsp90, and CHIP itself. Knockdown of Hsp70 partially protected the AR from 2-ME induced degradation (compare lanes 2 and 4 in both panels), but knockdown of Hsp90 failed to do so (compare lanes 2 and 6 in both panels). Knockdown of CHIP was more effective and significantly reduced 2-ME-induced degradation of the AR (compare lanes 2 and 8 in both panels). Similar results were observed when the CHIP was silenced by a second siRNA that targeted the 3′-UTR of the CHIP gene (siCHIP-2), (Supplementary Figure S6). These observations suggested that CHIP, and its interacting partner Hsp70 are involved in 2-ME-induced AR degradation. We did not observe additional protection of the AR when we knocked down Hsp70 or Hsp90 along with CHIP (compare lane 8 to lanes 12 and 14 in both panels), or when all the three components of the Hsp–CHIP complex were knocked down (compare lanes 8 and 16 in both panels).

MDM2 targets the AR when growth factors or cytokines induce its phosphorylation by PI3K/Akt. To assess MDM2 involvement in 2-ME-induced AR degradation, MDM2 was silenced by siRNA, which partially protected the AR in both LNCaP (Figure 4e) and C4-2 (Figure 4f) cells (compare lanes 2 and 18). The knockdown of both CHIP and MDM2 prevented AR degradation in C4-2 (Figure 4f) (compare lanes 1–2 and 21–22); however, this combination was not as effective in LNCap cells (Figure 4e). A recent report has shown that RNF6, another E3 ligase, polyubiquitinates the AR and regulates its transcriptional activity. We silenced RNF6 by siRNA, but as shown in Figures 4e and f, the AR was still degraded even when RNF6 was virtually absent (Supplementary Figure S7). Together, these data led us to conclude that the E3 ligases CHIP and MDM2, but not RNF6, are involved in 2-ME-induced AR degradation.

As the AR acts as a licensing factor, it should be degraded in the M phase of the cell cycle to allow initiation of the next cell cycle18 To determine whether 2-ME-induced AR degradation is a consequence of M phase cell cycle arrest (Figures 1a and b), we treated LNCaP, C4-2 and PC3-M cells with different concentrations of colchicine. As expected, colchicine treatment arrested cells in M phase (Supplementary Figures S8A, S8B and S8C). However, under these conditions AR protein degradation was not observed in LNCaP (Supplementary Figure S8D) and C4-2 (Supplementary Figure S8E) cells. These results suggest that 2-ME-induced AR degradation is not a consequence of M phase cell cycle arrest, but that M phase arrest is likely a consequence of AR degradation.

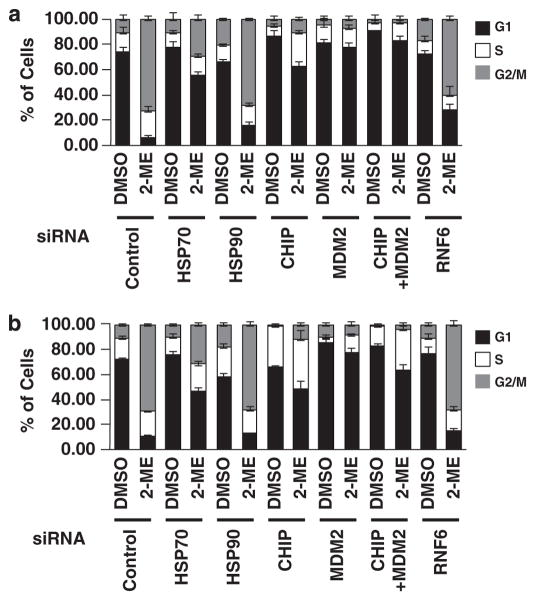

Protection of AR by silencing CHIP and MDM2 prevents mitotic arrest

To test the hypothesis that AR is involved in progression through mitosis, we interfered with AR degradation by knocking down the E3 ligases, CHIP and MDM2. Depletion of CHIP and MDM2, individually or in combination, abrogated the M phase arrest induced by 2-ME in LNCaP (Figure 5a) and C4-2 (Figure 5b) cells. In addition, knockdown of Hsp70, which partially protected the AR, partially abrogated M phase arrest. On the other hand, knockdown of Hsp90 or RNF6 failed to abrogate M phase cell cycle arrest. These findings further support the idea that 2-ME regulates the cell cycle in AR-positive prostate cancer cells by promoting proteasome-dependent degradation of the AR.

Figure 5.

Stabilization of AR by depletion of CHIP and MDM2. (a) LNCaP or (b) C4-2 cells were transfected with siRNA specific for indicated proteins. After 24 h, cells were treated with or without 2-ME (1 μM) for an additional 24 h, harvested, fixed, stained with PI, and DNA content was measured. Mean±s.d. of at least three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

The AR has a critical role in prostate cancer progression, in part through the transcriptional regulation of AR responsive genes. Decreasing androgen levels either through castration or pharmacologically by AR blockade are effective initial therapies for advanced prostate cancer patients, although relapse is inevitable.5,19 The AR not only mediates the effect of androgen on tumor initiation but also has a major role in the transition from androgen dependence to androgen independence.5,6,20 The AR is also known to be a licensing factor for AR-positive and androgen-sensitive prostate cancer cells and interacts with a number of other licensing factors including hZimp7, hZimp10 and SWI-SNF-like BRG1-associated factors at the origin of DNA replication.18,21,22 The AR also interacts with the prereplication complex proteins ORC2, Cdt1 and Cdc6.23 Recently, it has been shown that Cdc6 is under the direct transcriptional control of the AR, indicating that both G1 and S phase components of the cell cycle machinery may be regulated by AR.24,25 Thus, a strong rationale exists for searching for new drugs to stimulate downregulation of AR levels to treat castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Previous work showed 2-ME causes a G2/M arrest, and this was understood to involve its binding to the colchicine site on microtubules, at concentrations greater than 5 μM.26,27 We observed that much lower concentrations of 2-ME (that is, 0.5 μM) induced mitotic arrest in AR-positive cells (LNCaP, C4-2 and 22Rv1) but not in AR null PC3-M and RWPE1 cells. The presence of AR sensitized prostate cancer cells to 2-ME-induced mitotic arrest, and conversely, the absence of AR made cells more resistant to 2-ME.

How does AR sensitize cells to 2-ME induced mitotic arrest? One possibility for the role of the AR in regulating mitosis is that the AR transcriptionally activates genes, which are necessary for mitotic progression, and when AR is degraded, mitotic progression stalls. In support of this hypothesis, a recent report has documented that AR upregulates M-phase cell cycle genes in prostate cancer cells.28 Another related question is whether AR degradation is the cause of or the consequence of mitotic arrest. Our data clearly demonstrate that AR degradation is not the consequence of mitotic arrest, as the AR can be degraded in S phase (Figure 3). Furthermore, colchicine treatment produced mitotic arrest but not AR degradation (Supplementary Figure S8).

Our finding that AR is degraded through the activation of CHIP is consistent with the degradation of other nuclear receptors, which are also subject to post-transcriptional modifications that govern numerous facets of receptor function.29 Among them, ubiquitination has been demonstrated to signal receptor destruction, providing an absolute mechanism of AR inactivation.30 Several previous studies have demonstrated that E6-AP is an E3 ubiquitin ligase for AR ubiquitination.31 MDM2 is another E3 ligase whose ubiquitination activity requires phosphorylation of AR (by AKT), as well as deacetylation by histone deacetylase 1.29,30 The E3 U-box ligase Hsp70 N-terminus interacting protein (CHIP) has also been reported to be involved in AR degradation.32,33

The Hsp90/Hsp70-based chaperone machinery is required for CHIP activity. Hsp90 stabilizes associated client proteins, whereas Hsp70 interacts with a chaperone-dependent E3 ligase to promote protein degradation by polyubiquitination.34 Our data are consistent with these reports in that 2-ME-induced AR degradation requires Hsp70 and CHIP association. Silencing of Hsp70 partially abrogated 2-ME-induced AR degradation, likely because of incomplete knockdown of Hsp70, while silencing of Hsp90 failed to abrogate 2-ME-induced AR degradation.

We propose that CHIP is the primary E3 ligase, responsible for degrading the AR in response to 2-ME. We observed retarded mobility of CHIP in SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in response to 2-ME treatment of cells, and believe this is owing to post-translational modification. This change corresponded to enhanced degradation of AR. On the other hand, MDM2 levels were barely detectable in 2-ME treated cells (Figure 4, lane 2), and silencing of CHIP increased MDM2 levels. Our data are consistent with a reciprocal relationship between CHIP and MDM2 in AR degradation, which has been described previously.35 Phosphorylation of the AR has been shown recently to regulate the preference of MDM2 vs CHIP as the E3 ligase responsible for AR degradation.36 As CHIP is favored with impaired AR phosphorylation, we predict that 2-ME-induced AR degradation occurs with low AR phosphorylation and will test this hypothesis in subsequent studies. The possibility of 2-ME activating other E3 ligases that mediate AR degradation cannot be ruled out.

Interestingly, AR has been previously linked to G1/S progression. Litvinov et al. have suggested that AR functions as a licensing factor for DNA replication. AR normally is degraded in M phase, and loss of AR is required for licensing of DNA replication, hence knockdown of AR produces a G1 arrest, as knockdown prevents prereplication complex formation, which is required for licensing a new round of DNA replication. This is in keeping with both our AR as well as our CHIP knockdown data as CHIP knockdown stabiles AR, and therefore prevents its degradation at M phase possibly explain the G1 arrest. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that beside AR, CHIP and/or MDM2 might stabilize other cell cycle genes regulating cell cycle progression.

In summary, we show that 2-ME-induced degradation of the AR, and mitotic arrest are mediated by the Hsp70/CHIP complex. Our data reveal a previously unknown role for the AR in the regulation of mitotic progression. Stimulation of AR degradation through E3 ligase activation (in response to 2-ME or eventually other drugs) opens up the possibility of activating E3 ligases to decrease AR levels as a novel strategy for treating prostate cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Androgen-dependent human prostate carcinoma, LNCaP and androgen-independent human prostate carcinoma C4-2 and 22Rv1cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained in RPMI (Gibco-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) and human prostate carcinoma PC3-M cells (American Type Culture Collection) and PC3-M-AR (a generous gift of Dr. Bryce Paschal, University of Virginia) were maintained in DMEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Immortalized normal prostate epithelial cells RWPE1 from American Type Culture Collection were maintained in serum-free Keratinocyte media (Gibco) supplemented with epidermal growth factor and bovine pituitary extract. All cell lines were maintained in a 37 °C/5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

Chemicals

2-ME and colchicine were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

Cell proliferation assays

Cells were plated (2500 cells/well) in 96 well plates and treated with or without 2-ME for 24 h. Cell growth was monitored with the Alamar Blue assay (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA isolation and RT–PCR

Cells were treated with 2-ME for 24 h and total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen-Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. complementary DNA synthesis for mRNA detection was carried out using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system for RT–PCR (Invitrogen). mRNA was detected by qPCR using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Bio-Rad) in a Bio-Rad CFX96 cycler and quantified with Bio-Rad CFX manager software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

siRNA transfection

siRNA was transfected into LNCaP or C4-2 cells using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 2 × 105 cells were seeded in 6 cm dish in growth medium. Following day transfection complex (siRNA + RNAiMax) were added to the cells after washing once with phosphate-buffered saline, waited for 4–6 h, transfection complex were removed, washed cells twice with phosphate-buffered saline and replaced with growth medium. Twenty-four hour later drug was added and harvested after 24 h unless otherwise mentioned.

Western blotting and antibodies

For western blotting, cells were lysed in modified RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% Triton X–100, 50 mM NaF, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 40 mM β-glycerophosphate and 1 μM microcystin) supplemented with a protease inhibitor mix (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Unless otherwise described, 30 μg of protein were resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred, and immunoblotted with various antibodies. The antibodies used were antiAR (sc-7305), antiCHIP (sc-133066), and antiMDM2 (sc-56154), all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); antip53, antiGAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) and Phospho-H3 (S10) from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; and cyclin B1 (CC03, Calbiochem, Billerica, MA, USA), antiHsp70 (SPA-822, assay designs), antiHsp90 (ADI-SPA-845, Enzolifesciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA), and mouse monoclonal antibody antitubulin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich).

FACS analysis

Cells were harvested by trypsinization and then fixed with 70% ethanol for 24 h at 4 °C. Fixed cells were stained in 1 ml of propidium iodide solution (0.05% NP-40, 50 μg per ml propidium iodide, and 10 μg per ml RNase A) for at least 2 h at 4 °C. Stained cells were analyzed with a flow cytometer using CellQuest software (both from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), cell cycle phases were analyzed by ModFit LT V3.3.11(Mac, Verity Software House, Topshan, ME, USA).

Immunoprecipitation and ubiquitination assay

Cells were treated with or without 2-ME for one hour, harvested and lysed in modified radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer. Ubiquitinated proteins were immunoprecipitated by control beads or Tandem Ubiquitin Binding Entities (TUBEs) conjugated agarose beads (LifeSensors, 271 Great Valley Parkway, Malvern, PA, USA). Samples were resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoesis, and immunoblotted for AR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health grant 5R01CA142823-02 (to J. M. L.) as well as the Charles R. Burnett Jr and W. Griffin Burnett Fund. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

References

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiewer MJ, Augello MA, Knudsen KE. The AR dependent cell cycle: mechanisms and cancer relevance. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;352:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szostak MJ, Kyprianou N. Radiation-induced apoptosis: predictive and therapeutic significance in radiotherapy of prostate cancer (review) Oncol Rep. 2000;7:699–706. doi: 10.3892/or.7.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lara PN, Jr, Meyers FJ. Treatment options in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Invest. 1999;17:137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossmann ME, Huang H, Tindall DJ. Androgen receptor signaling in androgen-refractory prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1687–1697. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.22.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharifi N, Farrar WL. Androgen receptor as a therapeutic target for androgen independent prostate cancer. Am J Ther. 2006;13:166–170. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200603000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pertschuk LP, Macchia RJ, Feldman JG, Brady KA, Levine M, Kim DS, et al. Immunocytochemical assay for androgen receptors in prostate cancer: a prospective study of 63 cases with long-term follow-up. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1:495–503. doi: 10.1007/BF02303615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prins GS, Sklarew RJ, Pertschuk LP. Image analysis of androgen receptor immunostaining in prostate cancer accurately predicts response to hormonal therapy. J Urol. 1998;159:641–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fotsis T, Zhang Y, Pepper MS, Adlercreutz H, Montesano R, Nawroth PP, et al. The endogenous oestrogen metabolite 2-methoxyoestradiol inhibits angiogenesis and suppresses tumour growth. Nature. 1994;368:237–239. doi: 10.1038/368237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsukamoto A, Kaneko Y, Yoshida T, Han K, Ichinose M, Kimura S. 2-Methoxyestradiol, an endogenous metabolite of estrogen, enhances apoptosis and beta-galactosidase expression in vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:9–12. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yue TL, Wang X, Louden CS, Gupta S, Pillarisetti K, Gu JL, et al. 2-Methoxyestradiol, an endogenous estrogen metabolite, induces apoptosis in endothelial cells and inhibits angiogenesis: possible role for stress-activated protein kinase signaling pathway and Fas expression. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:951–962. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.6.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day JM, Newman SP, Comninos A, Solomon C, Purohit A, Leese MP, et al. The effects of 2-substituted oestrogen sulphamates on the growth of prostate and ovarian cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;84:317–325. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar AP, Garcia GE, Slaga TJ. 2-methoxyestradiol blocks cell-cycle progression at G(2)/M phase and inhibits growth of human prostate cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2001;31:111–124. doi: 10.1002/mc.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qadan LR, Perez-Stable CM, Anderson C, D’Ippolito G, Herron A, Howard GA, et al. 2-Methoxyestradiol induces G2/M arrest and apoptosis in prostate cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:1259–1266. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casarez EV, Dunlap-Brown ME, Conaway MR, Amorino GP. Radiosensitization and modulation of p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase by 2-Methoxyestradiol in prostate cancer models. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8316–8324. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal ML, Agarwal A, Taylor WR, Stark GR. p53 controls both the G2/M and the G1 cell cycle checkpoints and mediates reversible growth arrest in human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8493–8497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litvinov IV, Vander GDJ, Antony L, Dalrymple S, De Marzo AM, Drake CG, et al. Androgen receptor as a licensing factor for DNA replication in androgen-sensitive prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15085–15090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603057103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HJ, Chang C. Recent advances in androgen receptor action. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1613–1622. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2309-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee DK, Chang C. Endocrine mechanisms of disease: expression and degradation of androgen receptor: mechanism and clinical implication. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4043–4054. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang CY, Beliakoff J, Li X, Lee J, Sharma M, Lim B, et al. hZimp7, a novel PIAS-like protein, enhances androgen receptor-mediated transcription and interacts with SWI/SNF-like BAF complexes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2915–2929. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma M, Li X, Wang Y, Zarnegar M, Huang CY, Palvimo JJ, et al. hZimp10 is an androgen receptor co-activator and forms a complex with SUMO-1 at replication foci. EMBO J. 2003;22:6101–6114. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Antonio JM, Vander GDJ, Isaacs JT. DNA licensing as a novel androgen receptor mediated therapeutic target for prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:325–332. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin F, Fondell JD. A novel androgen receptor-binding element modulates Cdc6 transcription in prostate cancer cells during cell-cycle progression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4826–4838. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mallik I, Davila M, Tapia T, Schanen B, Chakrabarti R. Androgen regulates Cdc6 transcription through interactions between androgen receptor and E2F transcription factor in prostate cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:1737–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cushman M, He HM, Katzenellenbogen JA, Lin CM, Hamel E. Synthesis, antitubulin and antimitotic activity, and cytotoxicity of analogs of 2-methoxyestradiol, an endogenous mammalian metabolite of estradiol that inhibits tubulin polymerization by binding to the colchicine binding site. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2041–2049. doi: 10.1021/jm00012a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamel E, Lin CM, Flynn E, D’Amato RJ. Interactions of 2-methoxyestradiol, an endogenous mammalian metabolite, with unpolymerized tubulin and with tubulin polymers. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1304–1310. doi: 10.1021/bi951559s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q, Li W, Zhang Y, Yuan X, Xu K, Yu J, et al. Androgen receptor regulates a distinct transcription program in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cell. 2009;138:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaughan L, Logan IR, Neal DE, Robson CN. Regulation of androgen receptor and histone deacetylase 1 by Mdm2-mediated ubiquitylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:13–26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin HK, Wang L, Hu YC, Altuwaijri S, Chang C. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitylation and degradation of androgen receptor by Akt require Mdm2 E3 ligase. EMBO J. 2002;21:4037–4048. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao X, Mohsin SK, Gatalica Z, Fu G, Sharma P, Nawaz Z. Decreased expression of e6-associated protein in breast and prostate carcinomas. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1707–1712. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cardozo CP, Michaud C, Ost MC, Fliss AE, Yang E, Patterson C, et al. C-terminal Hsp-interacting protein slows androgen receptor synthesis and reduces its rate of degradation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;410:134–140. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00680-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He B, Bai S, Hnat AT, Kalman RI, Minges JT, Patterson C, et al. An androgen receptor NH2-terminal conserved motif interacts with the COOH terminus of the Hsp70-interacting protein (CHIP) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30643–30653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang AM, Morishima Y, Clapp KM, Peng HM, Pratt WB, Gestwicki JE, et al. Inhibition of hsp70 by methylene blue affects signaling protein function and ubiquitination and modulates polyglutamine protein degradation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:15714–15723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.098806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morishima Y, Wang AM, Yu Z, Pratt WB, Osawa Y, Lieberman AP. CHIP deletion reveals functional redundancy of E3 ligases in promoting degradation of both signaling proteins and expanded glutamine proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3942–3952. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chymkowitch P, Le May N, Charneau P, Compe E, Egly JM. The phosphorylation of the androgen receptor by TFIIH directs the ubiquitin/proteasome process. EMBO J. 2011;30:468–479. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.