Abstract

Purpose

Examine the role of perceived significant other's modeling or encouragement of dieting in young adults' disordered eating behaviors.

Design

Online survey data were collected (2008–2009) as part of an ongoing study examining weight and related issues in young people.

Setting

Participants were originally recruited as students at middle and high schools in Minnesota (1998–1999).

Subjects

1,030 young adults (mean age 25.3, 55% female, 50% white) with significant others.

Measures

Participants were asked if their significant other diets or encourages them to diet. Behaviors included unhealthy weight control, extreme weight control, and binge eating.

Analysis

General linear models estimated the predicted probability of using each behavior across levels of significant other's dieting or encouraging dieting, stratifying by gender and adjusting for demographics and BMI.

Results

Perceived dieting and encouragement to diet by significant others were common. Disordered eating behaviors were positively associated with significant other's dieting and encouragement to diet, particularly for females. In models including both perceived dieting and encouragement, encouragement remained significantly associated with disordered eating. For example, women's binge eating was almost doubled if their significant other encouraged dieting “very much” (25.5%) compared to “not at all” (13.6%, p=.015).

Conclusion

There is a strong association between disordered eating behaviors and perceived modeling and encouragement to diet by significant others in young adulthood.

Keywords: young adults; emerging adults; disordered eating; significant other; romantic relationship; social influence; Manuscript format: quantitative research; Research purpose: modeling/relationship testing; Study design: non-experimental; Outcome measure: behavioral; Setting: schools, state/national; Health focus: weight control; Strategy: behavior change; Target population age: young adults; Target population circumstances: race/ethnicity

Purpose

Disordered Eating

Unhealthy weight control behaviors such as skipping meals, fasting, and using diet pills are commonly reported by young people. Recent research with U.S. samples has shown that almost half of young adult females report skipping meals for weight control, and many reported more extreme behaviors such as diet pill use (20%) or self-induced vomiting (7%).1 Binge eating, characterized by eating large amounts of food with a sense of loss of control is also commonly reported.2,3 These behaviors are of concern in that they have been shown to predict the onset of more severe eating disorders and weight gain over time,1,2,4–7as well as depression and other medical and psychosocial morbidity.8,9

A large body of literature has examined various types of social influence on these disordered eating behaviors in adolescence, with a focus on peers, friends, parents and the media.10–13 However, young adulthood (ages 18–29) is developmentally distinct from both adolescence and adulthood. It is characterized by the gradual adoption of adult social roles, including the development of meaningful and lasting romantic relationships.14 With this shift comes an increasing emphasis on a significant other as a source of social and emotional support. Significant others commonly replace parents and peers to become primary sources of feedback, which can be either positive or negative. For instance, research has shown that significant others can be critical to their partner's self-image and self-evaluation, particularly in the domains of weight, shape and appearance satisfaction.15–19 Understanding the role significant others may play in young adults' disordered behaviors is desirable from the standpoint of prevention and intervention.

Significant Others and Health

Accumulated evidence demonstrates that marriage is associated with better physical and mental health for adults, and there is some indication that this benefit may extend to premarital romantic relationships.20–26 Married people exhibit lower morbidity and mortality than their unmarried counterparts, and tend to respond better to treatments and recover more readily when faced with significant health conditions.27–29 Likewise, married people typically practice more health protective and health promoting behaviors than those who are not married.30–34

Several studies have begun to delve more deeply into characteristics of romantic relationships, not necessarily within marriages, which may be associated with health, and findings suggest differences for men and women. Two lines of inquiry inform the present study. The first group of studies address weight-related concerns in relationship partners, while the second group of studies focuses on mechanisms that might underlie the association between significant others and their partners' health behaviors in variety of domains.

First, existing research has found that general relationship quality, functioning and satisfaction are associated with weight-related concerns, specifically that women who are in more satisfying relationships tend to have greater body satisfaction and are less likely to use unhealthy weight control strategies (e.g., diet pills, vomiting) than those who are less satisfied. 35–37 Beyond these global relationship features, several studies have also examined male partners' satisfaction with their female partner's body37–39 and found that men's dissatisfaction with their partner's body was associated with women's own body dissatisfaction. Along these lines, our previous work with the present sample has indicated that hurtful weight-related comments between significant others are common, and are associated with the development of disordered eating behaviors, particularly for women.40, 41

A second body of research has begun to explore specific mechanisms with regards to other health behaviors, such as dietary intake or high-risk sexual behavior.26,34,42 For example, Stephens and colleagues34 distinguished between spousal warnings and encouragement, finding that although both were associated with adherence to a medically recommended diet, encouragement – the more positive strategy – was associated with better adherence. Similarly, our previous work has shown that young adult women whose significant other had positive health behaviors and attitudes (e.g. modeling in physical activity, valuing physically activity and healthful eating) were significantly less likely to be overweight, tended to eat more fruits and vegetables and engage in more physical activity compared to women whose significant other did not have positive health behaviors and attitudes.26

In the present study, we address the intersection of these areas by exploring specific mechanisms within relationships that are associated with disordered eating and, based on previous findings, examine these separately for young men and women. Specifically, we hypothesize that a significant other's modeling of dieting and encouraging partner's dieting will be positively associated with young adults' unhealthy or extreme weight control and binge eating behaviors, and that these associations will be most evident for female participants. Furthermore, we test whether these associations differ by marital status. Because the bulk of the existing research on the influence of romantic partners on each other's health or health behaviors has been conducted with married adults (described above), questions remain about the extent to which influences between marital partners are similar or different for young adults in non-marital romantic relationships. The present study addresses this gap by using a large and diverse population-based sample of young adults who report having a significant other in their lives.

Methods

Study Design and Population

The present cross-sectional study uses data from Project EAT (Eating and Activity in Teens and Young Adults)-III, the third wave of an ongoing longitudinal study examining weight and related issues in young people. In the first wave of the study, middle and high school students at 31 public schools in the Minneapolis/St. Paul metropolitan area of Minnesota completed surveys and anthropometric measures during the 1998–1999 academic year.43,44 Project EAT-III re-surveyed the original participants in 2008–2009 as they transitioned through adolescence and into young adulthood. Of the original 4,746 participants, 1,304 (27.5%) were lost to follow-up for various reasons, primarily missing contact information from Wave 1 (n = 411) and no usable address found at Wave 3 (n = 712). In Wave 3, survey invitation letter containing the survey web address and a unique password, were mailed to the remaining 3,442 participants; non-responders were sent up to three reminder letters. Paper copies of the survey were available to those who requested them, and were mailed to all non-responders after two reminders. Internet tracking services were employed to identify correct addresses when any mailing was returned due to an incorrect address. Data were collected by the Health Survey Research Center at the University of Minnesota (http://www.sph.umn.edu/about/hsrc/) between November 2008 and October 2009. The University of Minnesota's Institutional Review Board Human Subjects Committee approved all protocols used in Project EAT.

A total of 1,030 males (45.2%) and 1,257 females (54.8%) completed Project EAT-III surveys, representing 66.4% of participants who could be contacted. The mean age of the sample at baseline was 15.0 and at follow-up was 25.3 (range 20 – 31). Additional details of the study design and sample are available elsewhere.45

Survey Development

The Project EAT survey was developed in Wave 1 and revised for use at subsequent waves in order to assess items of relevance to young people as they transitioned into young adulthood and developed more independent lifestyles. Several new items were added such as, relationship status and select behaviors and attitudes of a significant romantic partner. The follow-up survey was pre-tested by 27 young adults in focus groups and test-retest reliability was examined in a sample of 66 young adults. Additional details of the survey development process are described elsewhere.45

Measures

Three items regarding young adults' perceptions of their significant other's behavior and attitudes, of relevance to the current analysis, were included in the survey. Participants were asked to indicate if they had a significant other (“for example, boyfriend/girlfriend, spouse, partner;” yes/no). Those that responded affirmatively were further asked if their significant other “diets to lose weight or keep from gaining weight” (modeling; test-retest r=0.85), or “encourages me to diet to control my weight” (test-retest r=0.67). Response options ranged from “not at all” to “very much” for both items. These items were developed by the study team to mirror similar items regarding modeling and encouragement by parents and friends used in our previous work with adolescents.13,46–48

Three types of disordered eating behaviors were assessed by self-report. Unhealthy weight control behaviors were assessed with the question “Have you done any of the following things in order to lose weight or keep from gaining weight during the past year?” (yes/no for each method). Responses classified as unhealthy weight control behaviors included doing one or more of the following: 1) fasted; 2) ate very little food; 3) used food substitute (powder/special drink); 4) skipped meals; and 5) smoked more cigarettes (test-retest agreement=85%). Responses classified as extreme weight control behaviors included one or more of the following: 1) took diet pills; 2) made myself vomit; 3) used laxatives; and 4) used diuretics (test-retest agreement=96%). Binge eating was assessed with two questions “In the past year, have you ever eaten so much food in a short period of time that you would be embarrassed if others saw you (binge eating)?” and “During the times when you ate this way, did you feel you couldn't stop eating or control what or how much you were eating?” (yes/no). Those who indicated feeling loss of control were classified as binge eaters (test-retest agreement=89%).

Participant height and weight were assessed by self-report in Wave 3; these values were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) using the standard formula. Self-reported height and weight measures have been shown to be highly correlated with objectively measured values in adults.49–52 Furthermore, in a validation study among a sub-sample of 127 Project EAT-III participants, the correlation between measured and self-reported BMI values was r = 0.95. Cutpoints developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were used to categorize participants into those who were underweight or average weight (BMI < 25), overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30) and obese (BMI ≥ 30).53

Gender and race were assessed at Wave 1. Race/ethnicity was assessed with one survey item: “Do you think of yourself as (1) white, (2) black or African-American, (3) Hispanic or Latino, (4) Asian-American, (5) Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or (6) American Indian or Native American” and respondents were asked to check all that apply. This variable was dichotomized into white/ non-white for analysis due to small numbers in some categories.

Participants were also asked to characterize their relationship status. All those who reported they were married or had a same-sex domestic partner were considered “married” and were compared to those in other types of relationships.

Data Analysis

General linear models were used to test our hypotheses regarding participants' use of each type of disordered eating behavior across the four levels of significant other's modeling or encouraging dieting (separately), adjusting for the respondent's BMI category, race and marital status. Least square means from these models are interpreted as predicted probabilities of an affirmative response to dichotomous dependent variables after adjusting for covariates. Post-hoc tests were used to compare disordered eating behaviors between each category of perceived modeling or encouraging frequency, and t-tests of trend were used to detect a linear pattern across the four ordered levels of significant other's modeling and encouragement of dieting. Interaction terms of marital status and each significant other variable were included in models to test whether associations between significant other's dieting or encouragement to diet differed for married versus unmarried participants. Because modeling and encouraging had a moderate and statistically significant Spearman correlation (r=.44, p<.001), an additional model was run entering both modeling and encouragement simultaneously, adjusting for covariates, to determine if either method of social influence was more strongly associated with disordered eating behaviors after accounting for the other type of influence.

Due to gender differences in the use of disordered eating behaviors,1 and previous research demonstrating gender differences in the association between relationship variables and health behaviors,26,35,54 all models were stratified by gender a priori.

Because attrition from the baseline sample did not occur at random, in all analyses, the data were weighted using the response propensity method.55 Response propensities (i.e., the probability of responding to the Project EAT-III survey) were estimated using a logistic regression of response at follow-up on a large number of predictor variables from the Project EAT-I survey. Weights were additionally calibrated so that the weighted total sample sizes used in analyses for each gender cohort accurately reflect the actual observed sample sizes in those groups. The weighting method resulted in estimates representative of the demographic make-up of the original school-based sample, thereby allowing results to be more fully generalizable to the population of young people in the Minneapolis/St. Paul metropolitan area.

The weighted sample included 1,244 participants (522 males and 772 females) who indicated they had a significant other at Wave 3. This sample of young adults with significant others was 49.8% white, 15.0% African American, 5.7% Hispanic, 22.0% Asian, 2.3% Native American and 5.3% mixed/other race or ethnicity. One-third (32.3%) indicated that they were married.

Results

Approximately half (51.3%) of the sample was of normal weight or was underweight, 26.8% were overweight and an additional 22.0% were categorized as obese. Over 40% of the sample reported using unhealthy weight control behaviors in the past year, and this was more common among females (51.2%) than males (29.9%). Extreme weight control behaviors and binge eating were also common. Additional details of the sample and their disordered eating behaviors are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and unhealthy weight control behaviors of young adults with significant others (percent)

| Total | Young Adult Males n=522 | Young Adult Females n=772 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 49.8 (638) | 51.4 (265) | 48.7 (373) |

| African American | 15.0 (192) | 13.7 (71) | 15.8 (121) |

| Hispanic | 5.7 (73) | 5.7 (29) | 5.7 (44) |

| Asian | 22.0 (282) | 21.9 (113) | 22.0 (169) |

| Native American | 2.3 (29) | 1.4 (7) | 2.9 (22) |

| Mixed/other | 5.3 (67) | 5.9 (30) | 4.8 (37) |

| BMI category | |||

| Normal/underweight | 51.3 (658) | 44.4 (230) | 55.8 (428) |

| Overweight | 26.8 (344) | 35.0 (181) | 21.2 (163) |

| Obese | 22.0 (283) | 20.6 (107) | 22.9 (176) |

| Married | 32.3 (415) | 32.8 (169) | 32.0 (246) |

| Unhealthy WCBs (yes) | 42.6 (552) | 29.9 (156) | 51.2 (396) |

| Extreme WCBs (yes) | 14.3 (186) | 6.6 (35) | 19.5 (151) |

| Binge eating (yes) | 11.4 (148) | 7.2 (38) | 14.2 (110) |

WCB=Weight control behavior

Participants reported that their significant others tended to engage in dieting. Almost three-quarters of males reported that their significant others (predominantly female in this sample) dieted a little (23.7%), somewhat (33.7%) or very much (15.1%); 45.5% of females reported that their (predominantly male) significant others dieted (Table 2). Approximately half of participants (51.2% of males and 44.1% of females) reported that their significant other encourages them to diet.

Table 2.

Dieting-related behaviors of young adults' significant other (percent)

| Total | Young Adult Males | Young Adult Females | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Significant other diets to lose weight | |||

| Not at all | 43.6 (565) | 27.5 (144) | 54.5 (421) |

| A little | 21.4 (277) | 23.7 (124) | 19.9 (153) |

| Somewhat | 23.8 (308) | 33.7 (176) | 17.1 (132) |

| Very much | 11.2 (145) | 15.1 (79) | 8.6 (66) |

| Significant other encourages me to diet | |||

| Not at all | 53.1 (687) | 48.8 (255) | 55.9 (432) |

| A little | 18.3 (238) | 19.9 (104) | 17.3 (134) |

| Somewhat | 17.3 (224) | 21.2 (111) | 14.7 (113) |

| Very much | 11.3 (146) | 10.1 (53) | 12.1 (93) |

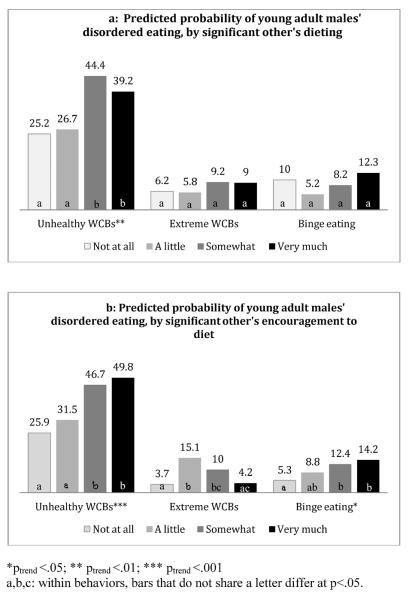

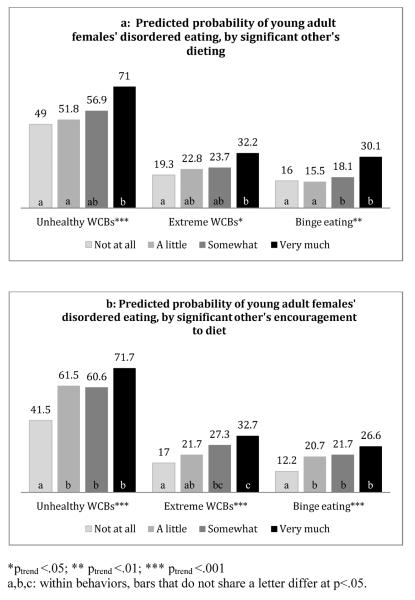

Figures 1 and 2 shows results of general linear models of unhealthy and extreme weight control behaviors and binge eating across levels of perceived modeling and encouragement of dieting by significant others (entered separately). As hypothesized, significant others' dieting behavior was significantly associated with participants' unhealthy weight control behaviors for both males and females. For example, among females who reported that their significant other did not diet at all, 49.0% reported using unhealthy weight control behaviors, and this prevalence was higher at each successive level of significant other dieting (51.8% among those whose significant other dieted a little, 56.9% for somewhat, and 71.0% among those whose significant other dieted “very much;” ptrend <.001, Figure 2a). This same pattern was evident for females' extreme weight control behaviors and binge eating. Similarly, perceived encouragement to diet by a significant other was associated with participants' own disordered eating behaviors (with the exception of males' extreme weight control). Post-hoc tests revealed that for unhealthy weight control behaviors and binge eating, young women who reported their significant other did not encourage them to diet at all were significantly less likely to report these behaviors compared to all other groups (p<.05). Significant linear trends in the expected direction were also apparent for most models.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Interaction terms modeling whether associations between significant other's dieting and encouragement and the three dependent variables were similar for married and unmarried participants were statistically significant in only one model. This is approximately what would be expected due to chance; interaction terms were therefore not included in further analysis.

In order to determine if perceived modeling or encouragement to diet by a significant other are more important, we included both in the model simultaneously. Significant others' dieting behavior no longer retained a significant trend relationship with disordered eating behaviors for males or females (Table 3). In contrast, significant others' encouragement to diet retained the significant linear associations seen in the previous models, even after adjusting for significant others' dieting and covariates. These finding indicate that perceived encouragement to diet is more strongly associated with participants' disordered eating behaviors than modeling of dieting behaviors.

Table 3.

Predicted probability of young adults' reporting disordered eating behaviors by significant other's dieting and encouragement to diet (mutually adjusted)^

| Young Adult Males | Young Adult Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Unhealthy WCBs | Extreme WCBs | Binge eating | Unhealthy WCBs | Extreme WCBs | Binge eating | |

| Significant other diets to lose weight | ||||||

| Not at all | 32.6a | 9.2a | 14.9a | 58.2a | 23.3a | 20.2a |

| A little | 32.5a | 4.8a | 7.8b | 56.5a | 25.1a | 17.6a |

| Somewhat | 45.6b | 8.0a | 8.4b | 58.3a | 24.2a | 18.5a |

| Very much | 37.3ab | 11.7a | 12.4ab | 65.6a | 29.0a | 27.8a |

| Ptrend=.208 | Ptrend=.401 | Ptrend=.597 | Ptrend=.286 | Ptrend=.373 | Ptrend=.149 | |

|

| ||||||

| Significant other encourages me to diet | ||||||

| Not at all | 27.8 a | 4.1a | 4.4 a | 43.3 a | 18.7 a | 13.6 a |

| A little | 30.6 ab | 16.6b | 10.8 b | 63.0 b | 22.7 ab | 22.2 b |

| Somewhat | 41.6 bc | 10.2ab | 13.9 b | 61.4 b | 27.9 ab | 22.8 b |

| Very much | 48.1 c | 2.8a | 14.4 b | 70.8 b | 32.3 b | 25.5 b |

| Ptrend=.003 | Ptrend=.463 | Ptrend=.022 | Ptrend<.001 | Ptrend=.006 | Ptrend=.015 | |

Significant linear trends shown in bold

WCBs=weight control behaviors

all models adjusted for BMI category, race (white/non-white) and marital status

: within behaviors, bars that do not share a superscript letter differ at p<.05.

Discussion

Results from the present study indicate that both perceived modeling of dieting behavior and perceived encouragement of dieting by a significant other are common in young adulthood. Both types of social influence were associated with disordered eating behaviors reported by young adult participants, typically in a dose-response pattern, after adjusting for covariates. These associations held for a variety of disordered eating behaviors, particularly for females, in support of study hypotheses. When examined in combined models, encouragement to diet was the more salient mode of influence on the behaviors of interest, and was significantly associated with disordered eating even at low levels of encouragement. Findings suggest that significant others are an important social influence on these behaviors and prevention and intervention efforts should address these interactions within romantic relationships, as they may contribute to unhealthy eating behaviors. Neither significant other's dieting nor encouragement to diet interacted significantly with marital status, suggesting that the associations reported here are equivalent for married and unmarried participants.

These results are consistent with previous studies finding a spousal or significant other effect on dietary behaviors26,34,41 as well as social influence by a romantic partner more generally.42, 56–58 They add to a small but growing body of work examining the characteristics of romantic relationships in young adults25,26,42 and extend this literature to disordered eating behaviors.

The present study also differs from previous research on social influence in ways that may be instructive. “Encouragement” is generally viewed as a positive type of social control, and has been associated with desirable behavior change.33,34 However, encouragement is most commonly operationalized as a supportive behavior (e.g. “help my partner think of substitutes for the unhealthy behavior,”33, p. 473) and contrasted with examples of negative social control such as warning of health consequences and repeated reminders to adopt a new behavior. However, encouragement to diet may be viewed as inherently critical and negative, as it implies dissatisfaction with the partner's weight or physical appearance, particularly in a generally healthy sample. Such “encouragement” may indeed be more hurtful than supportive. Results from the present study are consistent with our previous work examining weight-teasing and other hurtful weight-related comments made by a significant other, in which we found such comments to be common, and to be associated with disordered eating in young adults.40, 41

Strengths and Limitations

The current study has a number of noteworthy strengths. The sample was large, included both males and females, and was diverse with regards to race, economic status and marital status. Importantly, previous research with this age group relies almost exclusively on college student samples; the present study utilized a sample originally recruited as middle- and high school students who were in various settings as young adults. These features improve our ability to generalize to the population of young adults who are not often represented in research on disordered eating behavior. In addition, our survey included measures of two different means of social control by a significant other (modeling and encouraging), as well as numerous specific unhealthy weight control behaviors.

However, findings must also be viewed in light of some limitations. Specifically, the measure of encouragement was not defined for participants. “Encouragement” is typically viewed as a positive strategy for motivating behavior change; however, given the topic, this approach may in fact have been perceived by participants as negative or hurtful, and the specific content of “encouraging” comments or interactions is unknown. Similarly, only a single item assessing significant others' dieting was included, in order to minimize respondent burden in a long survey. We were therefore unable to test the association between significant others' modeling a specific behavior, such as binge eating, with the same behavior in participants. In addition, other characteristics of the significant other (such as his or her BMI) and the romantic relationship (such as longevity) were not available, but may be related to the strength of the influence of the significant other on young adults' disordered eating behaviors. It is also important to note that significant others were not themselves surveyed for the present study; measures regarding significant others are therefore best described as participants' perceptions of their significant others' dieting-related behaviors, which may differ from their actual behaviors. One might argue, however, that participant perceptions may be more salient than the significant others' behaviors themselves.59 Finally, the present study uses a cross-sectional design and a causal association cannot be inferred. Unfortunately, relevant survey items regarding significant others were only added to the most recent wave of Project EAT; future research should explore in greater depth the longitudinal development of romantic relationships and weight-related behaviors between partners.

Conclusions

Interventions designed to capitalize on the interactions of significant others regarding weight-related behaviors need to be mindful that this type of influence may operate differently than for other types of behavior, and may have unintended outcomes, including engagement in unhealthy behaviors. Results of the present study were robust across multiple measures of unhealthy eating behavior, particularly for females, and generally align with previous research regarding the influence of romantic partners on health behaviors.26,34,42

However, further research in this area is warranted to elucidate certain issues. For example, it may be important to collect data from the significant other in order to see how self-report of weight control behaviors compares to young adults' perceptions of the significant other's weight control attitudes and behaviors. Likewise, research on the role of the significant other in young adults' weight-related behaviors should be examined in the context of other important relationships, such as parents and friends, in order to obtain a fuller understanding of these social influences. Future research should also examine associations longitudinally in order to address temporality issues. In addition, a fuller understanding of what constitutes “encouragement” in this context would be useful in the design of relationship-based interventions; both qualitative and survey research with more precise measures of encouraging behaviors or comments would be instructive.

Although we cannot assume causality, or even temporality of associations, from the current cross-sectional, observational study, the findings suggest that one's significant other's weight-related behaviors and comments may have implications for one's own behaviors. Thus, it may be important to include significant others in interventions targeting weight control behaviors in young adults. For example, educating couples on how to be helpful, and not harmful, to each other in relation to weight control behaviors would be important. Such ideas include guiding couples to be physically active together, eat meals together, and cook together rather than use unhealthy weight control behaviors. In addition, mental and physical health care providers who work with young adults may want to ask about significant other's weight control behaviors and attitudes when assessing young adults' disordered eating behaviors in order to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the influences operating in the young adults life related to these behaviors.

So What?

What is already known on this topic?

Romantic partners and several relationship characteristics are associated with several health promoting behaviors. Mechanisms such as encouragement have been investigated with regards to weight status, dietary intake and physical activity, but specific influences on disordered eating behaviors among young adults have not been examined.

What does this article add?

Both perceived modeling of dieting behavior and encouragement of dieting by a significant other were positively associated with disordered eating behaviors in young adult participants, particularly for females. Perceived encouragement to diet was the more salient factor. Results were equivalent regardless of marital status.

What are the implications?

Significant others may be an important social influence on disordered eating behaviors, and prevention and intervention efforts should address interactions within romantic relationships. Although “encouragement” is generally associated with desirable behavior change, with regards to weight control it may be viewed as inherently critical and negative.

Acknowledgement

The project described was supported by Grant Number R01HL084064 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Guo J, Story M, Haines J, Eisenberg M. Obesity, disordered eating, and eating disorders in a longitudinal study of adolescents: How do dieters fare five years later? J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:559–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Larson NI, Eisenberg ME, Loth K. Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR. Prevalence and Correlates of Eating Disorders in Adolescents: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):714–723. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stice E, Cameron RP, Killen JD, Hayward C, Taylor CB. Naturalistic weight-reduction efforts prospectively predict growth in relative weight and onset of obesity among female adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(6):967–974. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patton GC, Selzer R, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Wolfe R. Onset of adolescent eating disorders: Population based cohort study over 3 years. BMJ. 1999 Mar 20;318(7186):765–768. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7186.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stice E, Agras WS. Predicting onset and cessation of bulimic behaviors during adolescence: A longitudinal grouping analyses. Behavior Therapy. 1998;29:257–276. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stice E, Presnell K, Shaw H, Rohde P. Psychological and behavioral risk factors for obesity onset in adolescent girls: A prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(2):195–202. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stice E, Hayward C, Cameron RP, Killen JD, Taylor CB. Body-image and eating disturbances predict onset of depression among female adolescents: A longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109(3):438–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katzman DK. Medical complications in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: A review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37(Suppl):S52–59. doi: 10.1002/eat.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paxton SJ, Schutz HK, Wertheim EH, Muir SL. Friendship clique and peer influences on body image concerns, dietary restraint, extreme weight-loss behaviors, and binge eating in adolescent girls. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108(2):255–266. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodgers R, Chabrol H. Parental attitudes, body image disturbance and disordered eating amongst adolescents and young adults: a review. European Eating Disorders Review. 2009 Mar;17(2):137–151. doi: 10.1002/erv.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Field AE, Javaras KM, Aneja P, et al. Family, peer, and media predictors of becoming eating disordered. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008 Jun;162(6):574–579. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.6.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C. The role of social norms and friends' influences on unhealthy weight-control behaviors among adolescent girls. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1165–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tantleff-Dunn S, Gokee JL. Interpersonal influences on body image development. In: Cash TF, Pruzinsky T, editors. Body Image: A Handbook of Theory, Research and Clinical Practice. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoelter JW. Relative effects of significant others on self-evaluation. Soc Psychol Q. 1984;47:255–262. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tantleff-Dunn S, Thompson JK. Romantic partners and body image disturbance: Further evidence for the role of perceived-actual disparities. Sex Roles. 1995;33(9/10):589–605. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felson RB. Reflected appraisal and the development of the self. Soc Psychol Q. 1985;48:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray S, Touyz SW, Beumont PJV. The influence of personal relationships on women's eating behavior and body satisfaction. Eating Disorders. 1995;3:243–252. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gove WR. Sex, marital status, and mortality. American Journal of Sociology. 1973 Jul;79(1):45–67. doi: 10.1086/225505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Key CR, Samet JM. The effect of marital status on stage, treatment, and survival of cancer patients. JAMA. 1987 Dec 4;258(21):3125–3130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waltz M, Badura B, Pfaff H, Schott T. Marriage and the psychological consequences of a heart attack: a longitudinal study of adaptation to chronic illness after 3 years. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27(2):149–158. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90323-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coombs RH. Marital status and personal wellbeing: A literature review. Family Relations. 1991;40:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith JC, Mercy JA, Conn JM. Marital status and the risk of suicide. Am J Public Health. 1988 Jan;78(1):78–80. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braithwaite SR, Delevi R, Fincham FD. Romantic relationships and the physical and mental health of college students. Personal Relationships. 2010;17:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berge JM, MacLehose R, Eisenberg M, Laska M, Neumark-Sztainer How significant is the `Significant Other': Associations between significant others' health behaviors and young adults' health outcomes. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2012;9(1):35–41. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waite L, Gallaher M. The case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier, and better off financially. 1st ed Doubleday; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Family relationships, social support and subjective life expectancy. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(4):469–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umberson D, Williams K, Powers D, Liu H, Needham B. You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47:3–16. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Umberson D. Family status and health behaviors: social control as a dimension of social integration. J Health Soc Behav. 1987 Sep;28(3):306–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eng PM, Kawachi I, Fitzmaurice G, Rimm EB. Effects of marital transitions on changes in dietary and other health behaviours in US male health professionals. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005 Jan;59(1):56–62. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markey CN, Markey PM, Schneider C, Brownlee S. Marital status and health beliefs: Different relations for men and women. Sex Roles. 2005;53(443-451) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tucker JS, Anders SL. Social control of health behaviors in marriage. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2001;31:467–485. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stephens MA, Rook KS, Franks MM, Khan C, Iida M. Spouses use of social control to improve diabetic patients' dietary adherence. Families, Systems, & Health. 2010;28(3):199–208. doi: 10.1037/a0020513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markey CN, Markey PM, Birch LL. Interpersonal predictors of dieting practices among married couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(3):464–475. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman MA, Dixon AE, Brownell KD, Whisman MA, Wilfley DE. Marital status, marital satisfaction, and body image dissatisfaction. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;26(1):81–85. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199907)26:1<81::aid-eat10>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrison KR, Doss BD, Perez M. Body image and disordered eating in romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2009;28(3):281–306. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pole M, Crowther JH, Schell J. Body dissatisfaction in married women: The role of spousal influence and marital communication patterns. Body Image. 2004;1(3):267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ambwani S, Strauss J. Love thyself before loving others? A qualitative and quantitative analysis of gender differences in body image and romantic love. Sex Roles. 2007;56:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisenberg ME, Berge JM, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Weight comments by family and significant others in young adulthood. Body Image. 2011;8(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisenberg ME, Berge JM, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Associations between hurtful weight-related comments by family and significant other and the development of disordered eating behaviors in young adults. J Behav Med. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9378-9. DOI: 10.1007/s10865-011-9378-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dennis MR. Compliance and intimacy: Young adults' attemps to motivate health-promoting behaviors by romantic partners. Health Communication. 2009;19(3):259–267. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1903_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neumark-Sztainer D, Croll J, Story M, Hannan PJ, French S, Perry C. Ethnic/racial differences in weight-related concerns and behaviors among adolescent girls and boys: Findings from Project EAT. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:963–974. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00486-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Croll J. Overweight status and eating patterns among adolescents: Where do youth stand in comparison to the Healthy People 2010 Objectives? Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):844–851. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, van den Berg P, Hannan PJ. Identifying correlates of young adults' weight behavior: Survey development. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35(6):712–725. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bauer KW, Laska MN, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Longitudinal and secular trends in parental encouragement for healthy eating, physical activity, and dieting throughout the adolescent years. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49(3):306–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paxton SJ, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls and boys: a five-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(5):888–99. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keery H, Eisenberg ME, Boutelle K, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Relationships between maternal and adolescent weight-related behaviors and concerns: the role of perception. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61(1):105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stewart A. The reliability and validity of self-reported weight and height. J Chronic Dis. 1982;35:295–309. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(82)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tehard B, van Liere MJ. Com Nougue C, Clavel-Chapelon F. Anthropometric measurements and body silhouette of women: Validity and perception. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(12):1779–1784. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90381-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuczmarski MF, Kuczmarski RJ, Najjar M. Effects of age on validity of self-reported height, weight, and body mass index: Findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palta M, Prineas RJ, Berman R, Hannan P. Comparison of self-reported and measured height and weight. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115(2):223–230. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed July, 2010];About BMI for Adults. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html.

- 54.Boyes AD, Fletcher GJ, Latner JD. Male and female body image and dieting in the context of intimate relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(4):764–768. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Little RJA. Survey nonresponse adjustments for estimates of means. International Statistical Review. 1986;54(2):139–157. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lewis MA, Rook KS. Social control in personal relationships: impact on health behaviors and psychological distress. Health Psychol. 1999 Jan;18(1):63–71. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anson O. Marital status and women's health revisited: The importance of a proximate adult. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:185–194. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hughes M, Gove WR. Living alone, social integration, and mental health. American Journal of Sociology. 1981;87(1):48–74. doi: 10.1086/227419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Markey CN, Markey PM. Romantic relationships and body satisfaction among young women. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:271–279. [Google Scholar]