Abstract

Paget-Schroetter is a rare diagnosis in the general population; however, it is more common in younger, physically active individuals. Clinicians must be familiar with the symptoms, physical examination, and initial imaging and treatment to expedite care and prevent possible life-threatening complications. Urgent referral to a regional specialist may improve the opportunity for thrombolysis to restore blood flow through the subclavian vein and to decrease the chance of pulmonary embolus, recurrent thrombosis, or need for vein grafting, as well as to improve the time to return to full activity (athletics and/or manual labor).

Keywords: Paget-Schroetter syndrome, effort thrombosis, upper extremity, sports medicine

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) symptoms can be somewhat vague; the treatment is typically performed by vascular surgeons.39 There are 3 distinct varieties; the most common is neurogenic, followed by venous and, finally, arterial. Paget-Schroetter syndrome (PSS), or effort thrombosis, is a subset of the venous subgroup. This syndrome was originally described in 1875 by Paget,29 followed by von Schroetter’s38 theory in 1884. A history of venous obstruction with vigorous exercise or activity is present in approximately 60% to 80% of cases, with an incidence of 1 to 2 per 100,000 individuals per year.16,19,22,34

This condition occurs in baseball,10,26 softball,28 wrestling,24 swimming,37 hockey,7 martial arts,41 backpacking,20 and billiards.17 Four cases were confirmed over an 11-year period tracking 1 major league team and 1 collegiate baseball team.10 A recent study identified 32 high-level athletes with effort thrombosis over a 10-year time frame, 14 of which were baseball players.26 Overhead workers and manual laborers are considered “industrial athletes,” subjecting their upper extremity to similar forces, which increases the likelihood of this condition. Clinicians should be aware of this condition and its symptoms because early intervention can be lifesaving.18

Anatomy/Pathogenesis

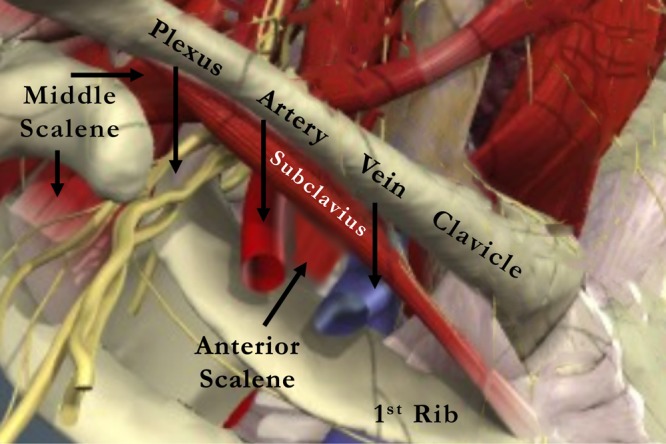

TOS can be caused by compression of the brachial artery and the brachial plexus passing through a triangular space created by the borders of the scalenus anticus muscle, scalenus medius muscle, and the first rib. The subclavian vein passes through a triangular space bordered by the first rib inferiorly, the scalenus anterior posteriorly, and the subclavius muscle and tendon medially just posterior to the intersection of the first rib and clavicle (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical photograph of an 18-year-old man who presented to our clinic with 6 weeks of tightness in his right arm following throwing and weight lifting. He denied any pain or neurologic symptoms.

Compression of the subclavian vein can occur with normal anatomy when the arm is in extremes of abduction and/or external rotation.2 Compression occurs because of a hypertrophied scalenus anterior or subclavius, increased generalized muscle bulk, pectoralis minor or subscapularis muscles, coracocostal ligament, pervenous phrenic nerve, osseous exostoses or distorted bony anatomy (congenital or posttraumatic), or fibrous bands.31,39 Interestingly, cervical ribs are more posterior structures, and while these may be the cause of neurogenic or arterial TOS, they are typically not the cause of venous TOS or effort thrombosis.33

Chronic compression of the vein leads to an inflammatory response in the soft tissues surrounding the vein, creating fibrotic connective tissue, which decreases the mobility of the vein.5 As the arm moves, the vein is stretched, and small tears occur, causing further damage and predisposing it to thrombosis formation. Recurrent partial thrombosis followed by recanalization can also occur.2,23 Over time, progressive intrinsic injury to the vein occurs, causing fibroelastic strictures, which creates turbulent blood flow and can lead to clot formation. Chronic compression may have relatively few, if any, symptoms until complete occlusion occurs, and even then, symptoms may be vague. Acute thrombosis typically results in more severe symptoms, such as severe swelling and pain, likely due to less collateral venous drainage.

Diagnosis

Presentation

Patients with effort thrombosis usually present after the subclavian vein has completely thrombosed with a bluish hue to the arm, discoloration, asymmetric muscle bulk or increased postworkout swelling that does not dissipate, heaviness, and pain in the affected upper extremity (Figure 2). Symptoms typically occur within 24 hours of the heavy upper extremity activity, as superficial veins become prominent in the upper extremity as well as the neck. Effort thrombosis typically affects the dominant arm. In overhead athletes, complaints can mimic shoulder or elbow problems, causing loss of velocity or control, arm heaviness, or a “dead arm” (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Venogram performed using conscious sedation and catheter placed in brachial vein. The venogram demonstrated an occlusion of the subclavian vein at the level of the clavicle/first rib with multiple collateral veins. A tPA infusion was performed; follow-up angiography noted resolution of thrombosis but residual stenosis due to scarring.

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of Paget-Schroetter

| Neurologic thoracic outlet syndrome |

| Arterial thoracic outlet syndrome |

| Malignant tumors of the head, neck, or arm |

| Pancoast tumor |

| Complex regional pain syndrome |

| Brachial neuritis |

| Cervical nerve root compression |

| Quadrilateral space syndrome |

| Peripheral nerve compression |

Physical Examination

The asymmetric swelling is typically obvious through visual inspection. Superficial venous engorgement is present, and the axilla can be palpated for hard linear structures that represent the clotted vein. A careful neurologic and arterial examination should be performed on all patients with similar presenting symptoms to rule out neurogenic or arterial TOS.

Provocative testing for TOS pertains more to the neurologic or arterial subtypes. In the Adson test,4 the head is turned toward the affected shoulder in slight extension and abduction while the patient inhales as the radial pulse is palpated.4 Hyperabduction and external rotation while checking for paresthesia or changes in radial pulse are included in the Wright test40 with both shoulders in 90° of abduction and external rotation and the elbows flexed to 90°. In this position, the patient opens and closes the hands repeatedly, which may reproduce symptoms.30 There is no specific physical examination finding that indicates effort thrombosis or PSS.32 Imaging studies are the most reliable method of diagnosis.

Imaging

The diagnostic study of choice is duplex ultrasonography. Sensitivity and specificity are excellent, ranging from 78% to 100% and 82% to 100%, respectively.9 Positional venous occlusion may require the ultrasonographer to manipulate the arm to reproduce the vascular compromise. A fresh clot may not always be visualized because it may still be echolucent; a key diagnostic feature is the vein’s lack of compressibility.19 As the thrombus grows, it becomes more echogenic secondary to the fibrosis. In some cases, the large peripheral collateral veins may be present.

If ultrasonography is inconclusive, venography can be performed in the same setting as treatment (Figure 3). However, the diagnosis can be missed if the cephalic vein is used for contrast injection.

Figure 3.

Diagram of the thoracic outlet, including the relationship of the subclavian artery and vein and brachial plexus to the bony and muscular architecture in the region.

Hypercoagulability Screening

The incidence of hypercoagulable conditions may be as high as 61% to 67%, especially in those without a clear anatomical cause of venous compression.8,10,13 The initial treatment for thrombosis is the same regardless of the cause.

Conservative Treatment

Nonsurgical treatment using anticoagulation alone can result in acute pulmonary embolism in 6% to 15%6 and residual venous obstruction in over 75% of patients.3 Outcomes are poor with the use of anticoagulation treatment as a single therapy with symptoms persisting in up to 91% of patients and up to 68% experiencing permanent disability.1,3,15,18,34

Operative Treatment

Catheter thrombolysis with subsequent first rib resection has emerged as the treatment of choice for PSS.19 Recanalization of the occluded vein is dependent on a number of factors.11 The time from clot formation to treatment is a major factor. After 10 days, the success rate of opening the vein diminishes to almost zero.11,21,33 Approximately 50% of veins treated at 6 weeks were partially opened, and none were completely opened.36 A poor prognostic indicator is the size of the clot with longer thrombi correlating with poor success at recanalization.12

Thrombolysis is not a benign procedure; it can result in defects in the vein that predispose to repeat clot formation.27 Angioplasty has not worked well because of the extrinsic nature of the compression, and venous stenting has resulted in stent fracture, deformation, and/or rethrombosis due to the unyielding surrounding structures.25 Concurrent decompression of the anterior aspect of the first rib in the first few days following thrombolysis is recommended.19,36

Decompression can be performed by removal of the first rib and/or medial clavicle. Transaxillary resection produces excellent cosmesis with good to excellent results in 85% to 95% of patients.35 Hemopneumothorax, long thoracic nerve injury, and incorrect rib removal can occur.19

Postoperative Rehabilitation/ Return to Play

Anticoagulation for 3 to 6 months following recanalization and decompression is recommended for deep venous thrombosis.19 Ultrasonography can monitor progress.19

In a recent study of 32 high-level athletes undergoing surgical management for venous TOS, 7 patients required repeat surgery (3 for bypass graft thrombosis, 2 for hemothorax, and 2 for wound hematoma or lymph leak).26 The risk for recurrent thrombosis or reoperation was relatively high (22%), and the average return to play was 4.4 months. There was no difference in the return to play time based on level of athlete (high school vs collegiate vs professional) or sport.26

During anticoagulation, passive range of motion can be initiated to prevent shoulder stiffness. Strengthening was allowed by 1 month in several studies,10,14 followed by a light toss program at 8 weeks, and interval throwing at 12 weeks.10 The average time to return to sports was 3.5 months, with a mean return to full activity of 4.4 months.26

Conclusion

PSS is rare. Immediate diagnosis can improve surgical outcomes and be lifesaving. The sooner treatment is initiated, the better the prognosis and the sooner the return to sport.

Footnotes

The following authors declared potential conflicts of interest: Nathan A. Mall received payment for manuscript preparation from Vindico Medical Education; George A. Paletta received payment for lectures from Arthrex; and Charles Bush-Joseph is a board member of The American Journal of Sports Medicine.

References

- 1. AbuRahma AF, Sadler D, Stuart P, Khan MZ, Boland JP. Conventional versus thrombolytic therapy in spontaneous (effort) axillary-subclavian vein thrombosis. Am J Surg. 1991;161:459-465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adams J, DeWeese J, Mahoney E, Rob C. Intermittent subclavian vein obstruction without thrombosis. Surgery. 1968;68:147-165 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adams JT, DeWeese JA. “Effort” thrombosis of the axillary and subclavian veins. J Trauma. 1971;11:923-930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adson W. Surgical treatment for symptoms produced by cervical rib and scalenus anticus muscle. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1947;85:687-700 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aziz S, Straehley CJ, Whelan TJ. Effort-related axillosubclavian vein thrombosis: a new theory of pathogenesis and a plea for direct surgical intervention. Am J Surg. 1986;152:57-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Walker FBT. Axillary and subclavian venous thrombosis: prognosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1934-1943 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Butsch JL. Subclavian thrombosis following hockey injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11:448-450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cassada DC, Lipscomb AL, Stevens SL, Freeman MB, Grandas OH, Goldman MH. The importance of thrombophilia in the treatment of Paget-Schroetter syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2006;20:596-601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chin EE, Zimmerman PT, Grant EG. Sonographic evaluation of upper extremity deep venous thrombosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:829-838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DiFelice GS, Paletta GA, Phillips BB, Wright RW. Effort thrombosis in the elite throwing athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:708-712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doyle A, Wolford HY, Davies MG, et al. Management of effort thrombosis of the subclavian vein: today’s treatment. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:723-729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Green R, Rosen R. The management of axillo-subclavianvenous thrombosis in the setting of thoracic outlet syndrome. In: Gloviczki P, ed. Handbook of Venous Disorders. 3rd ed. London, England: Hodder Arnold; 2008:292-298 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hendler MF, Meschengieser SS, Blanco AN, et al. Primary upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis: high prevalence of thrombophilic defects. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:330-337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hendrickson CD, Godek A, Schmidt P. Paget-Schroetter syndrome in a collegiate football player. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16:79-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heron E, Lozinguez O, Emmerich J, Laurian C, Fiessinger JN. Long-term sequelae of spontaneous axillary-subclavian venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:510-513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Horattas MC, Wright DJ, Fenton AH, et al. Changing concepts of deep venous thrombosis of the upper extremity: report of a series and review of the literature. Surgery. 1988;104:561-567 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hughes DG, Dixon PM. Pool players’ thrombosis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;295:1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hughes ES. Venous obstruction in the upper extremity. Br J Surg. 1948;36:155-163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Illig KA, Doyle AJ. A comprehensive review of Paget-Schroetter syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:1538-1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kolodinsky SD, Brandschwei FH. Axillary vein thrombosis in a female backpacker: Paget-Schroetter syndrome. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1989;40:230-231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee JT, Karwowski JK, Harris EJ, Haukoos JS, Olcott Ct. Long-term thrombotic recurrence after nonoperative management of Paget-Schroetter syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:1236-1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lindblad B, Tengborn L, Bergqvist D. Deep vein thrombosis of the axillary-subclavian veins: epidemiologic data, effects of different types of treatment and late sequelae. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1988;2:161-165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McLaughlin C, Pompa A. Intermittent obstruction of the subclavian vein. JAMA. 1939;113:1960-1963 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Medler RG, McQueen DA. Effort thrombosis in a young wrestler: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1071-1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meier GH, Pollak JS, Rosenblatt M, Dickey KW, Gusberg RJ. Initial experience with venous stents in exertional axillary-subclavian vein thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 1996;24:974-981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Melby SJ, Vedantham S, Narra VR, et al. Comprehensive surgical management of the competitive athlete with effort thrombosis of the subclavian vein (Paget-Schroetter syndrome). J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:809-820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Molina JE. Need for emergency treatment in subclavian vein effort thrombosis. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:414-420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nemmers DW, Thorpe PE, Knibbe MA, Beard DW. Upper extremity venous thrombosis: case report and literature review. Orthop Rev. 1990;19:164-172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paget J. Clinical Lectures and Essays. London, England: Longmans Green & Co; 1875 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roos DB. Congenital anomalies associated with thoracic outlet syndrome: anatomy, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Surg. 1976;132:771-778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roos DB, Edgar J. Poth lecture: thoracic outlet syndromes. Update 1987. Am J Surg. 1987;154:568-573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Safran MR. Nerve injury about the shoulder in athletes, part 2: long thoracic nerve, spinal accessory nerve, burners/stingers, thoracic outlet syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1063-1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thompson JF, Winterborn RJ, Bays S, White H, Kinsella DC, Watkinson AF. Venous thoracic outlet compression and the paget-schroetter syndrome: a review and recommendations for management. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34:903-910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tilney ML, Griffiths HJ, Edwards EA. Natural history of major venous thrombosis of the upper extremity. Arch Surg. 1970;101:792-796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Urschel HC, Razzuk MA. Neurovascular compression in the thoracic outlet: changing management over 50 years. Ann Surg. 1998;228:609-617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Urschel HC, Razzuk MA. Paget-Schroetter syndrome: what is the best management? Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:1663-1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vogel CM, Jensen JE. “Effort” thrombosis of the subclavian vein in a competitive swimmer. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13:269-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. von Schroetter L. Erkrankungen der Gefasse. In: Nathnagel Handbuch der Pathologie und Therapie. Vienna, Germany: Holder; 1884 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wood VE, Twito R, Verska JM. Thoracic outlet syndrome: the results of first rib resection in 100 patients. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:131-146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wright IS. The neurovascular syndrome produced by hyperabduction of the arms. Am Heart J. 1945;29:1-19 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zigun JR, Schneider SM. “Effort” thrombosis (Paget-Schroetter’s syndrome) secondary to martial arts training. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:189-190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]