Abstract

Management of diabetic patients with heart failure is a complex endeavor. The initial reluctance to use metformin in these patients has given way to a broader acceptance after clinical trials and meta-analyses have revealed that some of the insulin-sensitizing agents lead to adverse cardiovascular events. We have proposed that an increase of substrate uptake by the insulin-resistant heart is detrimental because the heart is already flooded with fuel. In light of this evidence, metformin offers a unique safety profile in the patient with diabetes and heart failure. Our article expands on the use of metformin in patients with heart failure. We propose that the drug targets both the source as well as the destination (in this case the heart) of excess fuel. We consider treatment of diabetic heart failure patients with metformin both safe and effective.

Keywords: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Heart Failure, Anti-diabetic Drugs

Introduction

Of the estimated 25.8 million people with the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in the United States, about 30% will develop heart failure(1), contributing to the exorbitant cost of diabetes. For example, in 2012 alone, the cost of diagnosed diabetes was $245 billion in total with $176 billion of that being secondary to direct medical costs(2). Cardiovascular complications accounted for the largest portion of this expenditure. Not surprisingly, the treatment of diabetes in heart failure has received a fair amount of attention recently(3–5). This prompted us to re-examine the choice of anti-diabetic drugs in patients with compromised cardiac function. Prominent amongst those drugs is metformin, the safety and efficacy of which will be discussed in this article. Our article follows a review on the use of antidiabetic drugs in patients with heart failure in which we proposed that the management of diabetes in heart failure patients should target the source, rather than the destination, of excess fuel(6).

Congestive Heart Failure and Diabetes

Heart failure has been defined as a “clinical syndrome caused by an abnormality of the heart but recognized by a characteristic pattern of hemodynamic, renal, neural, and hormonal responses”(7). In this review we prefer to define heart failure as a clinical syndrome that begins and ends with the heart. With that in mind, it seems appropriate to ask the question: Does the metabolic stress of type 2diabetes mellitus adversely affect structure and function of the heart?

Diabetes is a well known risk factor for coronary artery disease and its consequences. However, the relationship of diabetes with heart failure is still not well understood. As early as 1974, investigators from the Framingham study determined that patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease had a significantly increased risk of progressing to heart failure that was not explained by increased atherogenesis or coronary artery disease alone(8). For example, the risk of progression to heart failure in patients with diabetes in the study was increased four-fold in men, and more than six-fold in women, particularly in patients being treated with insulin, irrespective of other cardiovascular risk factors. Subsequent studies (9–11) have confirmed this observation, and have been reviewed by us before (12).

So what do we know? We know that patients with diabetes exhibit cardiac structural changes (13). Clinical studies have shown that diabetes is associated with concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, increased cardiac mass and mildly reduced systolic function(14). Histological studies of autopsy and biopsy specimens demonstrate that diabetic humans and animals made diabetic share a constellation of cardiac morphological abnormalities, including myocyte hypertrophy, perivascular fibrosis, and increased quantities of matrix collagen, myocelluar lipid droplets, and cell membrane lipids(15, 16). These morphologic changes, especially when considered together with the changes in myocardial calcium metabolism and contractile protein composition observed in experimental diabetes, are consistent with clinically significant impairment in diastolic compliance(12), and often also with impaired systolic function(17). Indeed there is a downregulation of myocyte specific enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C) and MEF2C regulated gene expression in diabetic patients with nonischemic heart failure(18). MEF2C regulates muscle development and stress response. It is also a regulator of several genes of intracellular Ca2+ and glucose metabolism. This has given rise to the hypothesis of glucose-regulated changes in gene expression and the involvement of glucose metabolism in isoform switching of sarcomeric proteins characteristic for the fetal gene program(19).

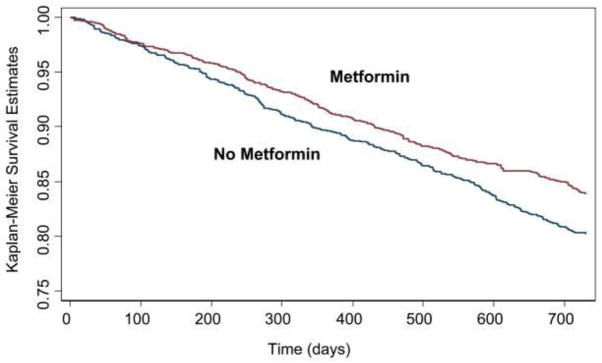

In addition, over the past few years there has been a lot of study into the relationship between diabetes, and optimal diabetes treatment in heart failure. Recent experience with the use of insulin sensitizing agents in heart failure has revealed that thiazolidinediones worsen cardiac function leading to premature cardiovascular death and disability(4, 20). Similar observations have previously been made with sulfonylureas, and in some cases, with insulin. In fact, recent studies have shown us that tight control of diabetes in heart failureoften involving insulin use, actually had a detrimental effect on mortality, as seen in the ACCORD(21) and NICE-SUGAR(22) studies. In contrast, the long-term use of metformin has not only been safe(5), but also mostly favorable, showing improved mortality and morbidity noted in several studies(23, 24). (Figure)

Figure.

Kaplan-Meier curves and metformin treatment in a propensity score-matched, national cohort of 6185 patients with heart failure and diabetes treated in ambulatory clinics at Veterans Administration medical centers. In this cohort, 561 patients were treated with metformin. Metformin treatment was associated with lower rates of mortality. Probability value = 0.01 (log-rank). From Aguilar et al (24), with permission from the authors and publisher.

What could be the reason for this unexpected observation? One would assume that if a serum glucose level within normal limits is an optimal end point, then achieving this milestone would be enough to reverse the increased risks of heart failure seen in diabetes patients. We and others have previously argued that prior randomized studies have used incorrect end points(4, 20). In addition, systemic insulin resistance is a hallmark of heart failure(25). Could insulin resistance perhaps serve as a protective mechanism in this condition preventing excess fuel accumulation in peripheral tissues? As observed in a prior meta-analysis(26) and discussed by Khalaf and Taegtmeyer in 2010(27), poor heart function might actually be worsened by an increased supply of fuel. In that case, the presence of insulin sensitizing agents would increase glucose uptake by a heart already flooded with fuel. If this hypothesis holds true, then the presence of heart failure would require the use of agents that decrease the supply of glucose, and not those that increase its utilization by the tissues. One such agent that reduces the supply of glucose is metformin, which both inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis and glucose production. Indeed metformin reduces mortality in ambulatory patients with diabetes and heart failure(24), as already mentioned (Figure), but metformin also has direct actions on the heart, as will be discussed next.

Pharmacology of Metformin

It is well established that metformin increases the activity of the AMP-dependent protein kinase (AMPK)(28, 29). The importance of this lies in the fact that activated AMPK stimulates fatty acid oxidation, glucose uptake, and non-oxidative metabolism leading to reduction of lipogenesis and gluconeogenesis which results in decreased rates of hepatic gluconeogenesis, decreased hepatic glucose output, rates of fatty acid oxidation, and lower blood glucose levels(28, 29). A novel mechanism by which metformin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis has been proposed by Birnbaum and his coworkers (30), which involves the inhibition of adenylate cyclase by AMPK, reducing the effects of glucagon on cAMP and protein kinase A (PKA) and thus reducing the ability of PKA to promote gluconeogenesis. Treatment of mice with metformin mimics the benefits of calorie restriction and improves physical performance and lifespan in mice (31).

Since 2009, experiments in animals have shown that metformin can also attenuate both ischemia-reperfusion injury and the process of remodeling and the development of heart failure(32–34). In a recent study(32), it was demonstrated that reperfusion is not needed for the beneficial effects of metformin on myocardial remodeling. Several different mechanisms may contribute to this protective effect. As mentioned above, metformin activates the enzyme 5′ AMP-activated kinase (AMPK), and it also activates eNOS, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-g coactivator-(PGC) 1a, which is a regulator of cellular energy substrate metabolism. Metformin also reduces the collagen expression that occurs after coronary artery ligation(34). In addition, despite the fact that metformin inhibits complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, treatment with metformin appears to attenuate the mitochondrial dysfunction in the failing myocardium(35). In addition to direct effects of metformin on the heart muscle, metformin also decreases plasma insulin concentration, while further contributing to a correction of the dysregulated metabolic state. Recent observations have shown that insulin signaling can promote cardiac remodeling(20, 36). This effect of limitation of myocardial fibrosis by metformin was also reported in experimental heart failure models induced by rapid pacing(33), and pressure overload(34). In both studies, the myocardial expression of the profibrotic cytokine transforming growth factor (TGF)-b1 was reduced by metformin. Interestingly, these inhibitory effects on collagen synthesis were independent from AMPK activation.

However, the main action of metformin in the heart itself is its role as activator of AMPK. AMPK plays also a pivotal role in preserving myocardial viability during myocardial infarction. Immediately after the onset of myocardial ischemia, AMPK is phosphorylated, and remains active for more than 24 h following reperfusion (37). By increasing flux through the pathways of ATP synthesis and by decreasing ATP utilization, AMPK contributes to maintain normal cellular energy stores during ischemia. Studies in transgenic mice with AMPK deficiency have shown variable results: AMPK activation during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion may be crucial to prevent apoptosis and functional decline(38). Therefore, administration of a single dose of metformin can potently reduce myocardial infarct size by activation of multiple, and probably parallel, intracellular pathways. These include activation of AMPK and eNOS, and increased adenosine receptor stimulation. In addition, the activation of several kinases of the reperfusion injury salvage kinase (RISK) pathway, result in the prevention of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) opening at reperfusion(39).

The observations that metformin can effectively prevent reperfusion injury implies that it can limit infarct size in patients suffering an acute myocardial infarction even when given at the time of the reperfusion therapy. However, infarct size per se is not the only predictor of the long-term morbidity and mortality in patients with a myocardial infarction(40, 41). Following ischemia-reperfusion injury, a complex cascade of events occurs both in the ischemic and non-ischemic parts of the heart, so called “ remodeling” which includes inflammation, fibrosis, ventricular wall thinning and dilation(42). Remodeling will induce clinically overt heart failure in a significant number of post-infarction patients. In addition, remodeling does not only occur in the setting of ischemia-reperfusion injury, but also in patients with cardiac volume overload, for example, due to valvular disease, and pressure overload such as in hypertension. An increased susceptibility to ischemia and reperfusion injury has been observed in hearts from old rats with diabetes, most likely as a consequence of impaired Akt signaling due to chronic Akt activation(43). Therefore, therapies that limit ischemia-reperfusion injury and prevent post-infarction remodeling are needed, in particular in patients with diabetes. Could metformin be that therapy? Our work on glucose regulation of load induced mTOR signaling and the endoplasmic reticulum stress response has shown that metformin reduces glucose 6-phosphate levels through tight coupling of glucose uptake and oxidation by the heart (44). Metformin also improves cardiac efficiency through reducing ER stress, and, presumably, rates of myocardial protein turnover (44).

Meformin and Heart Failure: The Big Picture

As mentioned, metformin has several modes of action. Although metformin increases peripheral sensitivity to insulin, its main action is to decrease gluconeogenesis in the liver. It therefore serves two roles: decreasing glucose synthesis as well as, to a lesser extent, increasing glucose utilization. Prescribed in the United States for over twenty years (and averaging up to 48 million prescriptions a year), metformin has long been one of the most popular and effective medications for the type 2 diabetic. Its present role in patients with heart failure could not have been foreseen owing to the relationship of its precursor, phenformin, and the unfortunate observation that showed increased incidence of fatal lactic acidosis at therapeutic doses in patients with diabetes(45, 46). Due to this effect, the FDA delayed approval for use of metformin patients with type 2 diabetes. When approval was finally granted in 1995, it was done with the condition that package inserts include strong warnings of the potential risks. When initial reports revealed that the risk of lactic acidosis was worse in patients with renal insufficiency and heart failure, these two conditions were included as contraindications to use(47, 48). As a result, most studies of metformin use in the United States prior to 2007 saw no patients with heart failure. However, somehow the medical community chose to ignore these recommendations, and a host of observational studies were able to revisit this treatment recommendation to show that, at least in patients with heart failure and diabetes mellitus, treatment with metformin results in improved mortality, regardless of renal status(24, 35). Most recently, Eurich et al performed a meta-analysis of studies performed in 2010 to evaluate just this question(49). Based on studies done on a total of 34 000 patients, the totality of evidence pointed to the use of metformin as the treatment of choice for patients with diabetes and heart failure. Also in 2010 in the widely acclaimed “Cochrane Review” a comprehensive search was performed of electronic data bases to identify studies of metformin treatment (50). There was no evidence that metformin was associated with increased risk of lactic acidosis.

In addition to its effects in patients with heart failure, metformin also has some positive effects on ameliorating insulin resistance. Cittadini et al (51) studied genetically modified insulin resistant rats which showed decreased evidence of left ventricular remodeling when treated with metformin. A small study evaluating the effect of metformin on insulin resistant adults with heart failure during exercise also showed that metformin improved the insulin resistance measured, and increased the VE/VCO2 slope (the ratio of minute ventilation to carbon dioxide production), but had no impact on max VO2(52). Most certainly, further investigation is needed.

Conclusions

The drivers of cardiac failure are three distinct factors: hemodynamic stress, neuro-humoral stress, and metabolic stress, including disorders in fuel metabolism associated with insulin resistance(53). While modern treatment of heart failure, by use of beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, and diuretics, have successfully countered the neuro-humoral axis (54), metabolic stress has been largely ignored until recently (55). Metformin ameliorates metabolic stress on the heart by reducing blood glucose levels using two different modes of action: reduced gluconeogenesis and enhanced glucose uptake with the tight coupling to oxidation by the peripheral tissues. We propose that counteracting metabolic stress with an agent such as metformin is of equal importance for reversal of cardiac dysfunction as counteracting neuro-humoral stress. To answer the title’s question: Treatment of diabetic heart failure patients with metformin can be regarded as safe and effective. Whether this treatment strategy should be limited to those with frank diabetes, or could also be expanded for use in all patients who exhibit signs of insulin resistance would be an interesting subject for further study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roxy A. Tate for expert editorial assistance. Work in H.T.’s lab is supported by the NHLBI (R01-HL061483 and R01-HL073162.)

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Heinrich Taegtmeyer, Ijeoma Ananaba Ekeruo and Amirreza Solhpour declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, Gregg EW, Ford ES, Geiss LS, Bainbridge KE, Fradkin JE. Prevalence of diabetes and high risk for diabetes using A1c criteria in the U.S. Population in 1988–2006. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):562–568. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):1033–1046. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson C, Olesen JB, Hansen PR, Weeke P, Norgaard ML, Jorgensen CH, Lange T, Abildstrom SZ, Schramm TK, Vaag A, et al. Metformin treatment is associated with a low risk of mortality in diabetic patients with heart failure: A retrospective nationwide cohort study. Diabetologia. 2010;53(12):2546–2553. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nissen SE. The rise and fall of rosiglitazone. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(7):773–776. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••5.Shah DD, Fonarow GC, Horwich TB. Metformin therapy and outcomes in patients with advanced systolic heart failure and diabetes. J Card Fail. 2010;16(3):200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.10.022. A retrospective cohort study that included 401 patients with DM and severe heart failure followed between 1994 and 2008. Although there was a trend to improvement of outcomes in the patients on metformin, the results were not statistically significant. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khalaf KI, Taegtmeyer H. After Avandia: The use of antidiabetic drugs in patients with heart failure. Tex Heart Inst J. 2012;39(2):174–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purcell IF, Poole-Wilson PA. Heart failure: Why and how to define it? Eur J Heart Fail. 1999;1(1):7–10. doi: 10.1016/S1388-9842(98)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannel WB, Hjortland M, Castelli WP. Role of diabetes in congestive heart failure: The Framingham Study. Am J Cardiol. 1974;34(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(74)90089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichols GA, Hillier TA, Erbey JR, Brown JB. Congestive heart failure in type 2 diabetes: Prevalence, incidence, and risk factors. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(9):1614–1619. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.9.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertoni AG, Tsai A, Kasper EK, Brancati FL. Diabetes and idiopathic cardiomyopathy: A nationwide case-control study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(10):2791–2795. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iribarren C, Karter AJ, Go AS, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Sidney S, Selby JV. Glycemic control and heart failure among adult patients with diabetes. Circulation. 2001;103(22):2668–2673. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.22.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taegtmeyer H, McNulty P, Young ME. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in diabetes: Part I: General concepts. Circulation. 2002;105(14):1727–1733. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012466.50373.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Factor SM, Borczuk A, Charron MJ, Fein FS, van Hoeven KH, Sonnenblick EH. Myocardial alterations in diabetes and hypertension. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1996;31(Suppl):S133–142. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(96)01241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Paranicas M, O’Grady MJ, Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz RR, Robbins D, Rhoades ER, Howard BV. Impact of diabetes on cardiac structure and function: The Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 2000;101(19):2271–2276. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.19.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardin NJ. The myocardial and vascular pathology of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Coron Artery Dis. 1996;7(2):99–108. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199602000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhalla NS, Liu X, Panagia V, Takeda N. Subcellular remodeling and heart dysfunction in chronic diabetes. Cardiovasc Res. 1998:40239–247. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald MR, Petrie MC, Hawkins NM, Petrie JR, Fisher M, McKelvie R, Aguilar D, Krum H, McMurray JJ. Diabetes, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(10):1224–1240. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Razeghi P, Young ME, Cockrill TC, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Downregulation of myocardial myocyte enhancer factor 2c and myocyte enhancer factor 2c-regulated gene expression in diabetic patients with nonischemic heart failure. Circulation. 2002;106(4):407–411. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000026392.80723.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young ME, Yan J, Razeghi P, Cooksey RC, Guthrie PH, Stepkowski SM, McClain DA, Tian R, Taegtmeyer H. Proposed regulation of gene expression by glucose in rodent heart. Gene Regul Syst Bio. 2007:1251–262. doi: 10.4137/grsb.s222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benbow A, Stewart M, Yeoman G. Thiazolidinediones for type 2 diabetes. All glitazones may exacerbate heart failure. BMJ. 2001;322(7280):236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC, Jr, Bigger JT, Buse JB, Cushman WC, Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F, Grimm RH, Jr, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2545–2559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, Blair D, Foster D, Dhingra V, Bellomo R, Cook D, Dodek P, Henderson WR, et al. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1283–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selvin E, Bolen S, Yeh HC, Wiley C, Wilson LM, Marinopoulos SS, Feldman L, Vassy J, Wilson R, Bass EB, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes in trials of oral diabetes medications: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2070–2080. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••24.Aguilar D, Chan W, Bozkurt B, Ramasubbu K, Deswal A. Metformin use and mortality in ambulatory patients with diabetes and heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;4(1):53–58. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.952556. A multicenter retrospective cohort study that studied metformin use in ambulatory patients with DM and CHF. Here, metformin use was associated with a significantly lower rate of mortality. Surprisingly, in this study the effect of the use of metformin on the rate of hospitalizations was minimal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingelsson E, Sundstrom J, Arnlov J, Zethelius B, Lind L. Insulin resistance and risk of congestive heart failure. JAMA. 2005;294(3):334–341. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(24):2457–2471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••27.Khalaf KI, Taegtmeyer H. Insulin sensitizers and heart failure: An engine flooded with fuel. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12(6):399–401. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0158-7. A concise review of the literature, drawing special attention to the present difficulty in treating patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B. Goodman and Gillman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York: McGraw Hill Professional Publications; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardie G. AMPK: A target for drugs and natural products with effects on both diabetes and cancer. Diabetes. 2013;62(7):2164–2172. doi: 10.2337/db13-0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller RA, Chu Q, Xie J, Foretz M, Viollet B, Birnbaum MJ. Biguanides suppress hepatic glucagon signalling by decreasing production of cyclic AMP. Nature. 2013;494(7436):256–260. doi: 10.1038/nature11808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin-Montalvo A, Mercken EM, Mitchell SJ, Palacios HH, Mote PL, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Gomes AP, Ward TM, Minor RK, Blouin MJ, et al. Metformin improves healthspan and lifespan in mice. Nat Commun. 2013:42192. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin M, van der Horst IC, van Melle JP, Qian C, van Gilst WH, Sillje HH, de Boer RA. Metformin improves cardiac function in a nondiabetic rat model of post-MI heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301(2):H459–468. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00054.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasaki H, Asanuma H, Fujita M, Takahama H, Wakeno M, Ito S, Ogai A, Asakura M, Kim J, Minamino T, et al. Metformin prevents progression of heart failure in dogs: Role of AMP-activated protein kinase. Circulation. 2009;119(19):2568–2577. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.798561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •34.Xiao H, Ma X, Feng W, Fu Y, Lu Z, Xu M, Shen Q, Zhu Y, Zhang Y. Metformin attenuates cardiac fibrosis by inhibiting the TGFbeta1-SMAD3 signalling pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87(3):504–513. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq066. A rodent animal study investigating cardioprotective effects of metformin. Specifically the role of metformin in decreasing cardiac fibrosis was investigated and a pathway was proposed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gundewar S, Calvert JW, Jha S, Toedt-Pingel I, Ji SY, Nunez D, Ramachandran A, Anaya-Cisneros M, Tian R, Lefer DJ. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by metformin improves left ventricular function and survival in heart failure. Circ Res. 2009;104(3):403–411. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimizu I, Minamino T, Toko H, Okada S, Ikeda H, Yasuda N, Tateno K, Moriya J, Yokoyama M, Nojima A, et al. Excessive cardiac insulin signaling exacerbates systolic dysfunction induced by pressure overload in rodents. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(5):1506–1514. doi: 10.1172/JCI40096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calvert JW, Gundewar S, Jha S, Greer JJ, Bestermann WH, Tian R, Lefer DJ. Acute metformin therapy confers cardioprotection against myocardial infarction via AMPK-eNOS-mediated signaling. Diabetes. 2008;57(3):696–705. doi: 10.2337/db07-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell RR, 3rd, Li J, Coven DL, Pypaert M, Zechner C, Palmeri M, Giordano FJ, Mu J, Birnbaum MJ, Young LH. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates ischemic glucose uptake and prevents postischemic cardiac dysfunction, apoptosis, and injury. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(4):495–503. doi: 10.1172/JCI19297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Reperfusion injury salvage kinase signalling: Taking a risk for cardioprotection. Heart Fail Rev. 2007;12(3–4):217–234. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hausenloy DJ. Cardioprotection techniques: Preconditioning, postconditioning and remote conditioning (basic science) Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(25):4544–4563. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319250004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: A neglected therapeutic target. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(1):92–100. doi: 10.1172/JCI62874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling--concepts and clinical implications: A consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an international forum on cardiac remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(3):569–582. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whittington HJ, Harding I, Stephenson CI, Bell R, Hausenloy DJ, Mocanu MM, Yellon DM. Cardioprotection in the aging, diabetic heart: The loss of protective akt signalling. Cardiovasc Res. 2013 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••44.Sen S, Kundu BK, Wu HC, Hashmi SS, Guthrie P, Locke LW, Roy RJ, Matherne GP, Berr SS, Terwelp M, et al. Glucose regulation of load-induced mTOR signaling and ER stress in mammalian heart. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(3):e004796. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.004796. This study shows for the fist time that an intermediary metabolie (glucose 6-phosphate, G6P) regulates mTOR, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response and contratile efficiency in animal models and the failing human heart. Metformin improves contractile function by reducing G6P levels and ER stress. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luft D, Schmulling RM, Eggstein M. Lactic acidosis in biguanide-treated diabetics: A review of 330 cases. Diabetologia. 1978;14(2):75–87. doi: 10.1007/BF01263444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang CT, Chen YC, Fang JT, Huang CC. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis: Case reports and literature review. J Nephrol. 2002;15(4):398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sulkin TV, Bosman D, Krentz AJ. Contraindications to metformin therapy in patients with niddm. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(6):925–928. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Misbin RI, Green L, Stadel BV, Gueriguian JL, Gubbi A, Fleming GA. Lactic acidosis in patients with diabetes treated with metformin. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(4):265–266. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801223380415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eurich DT, Weir DL, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Johnson JA, Tjosvold L, Vanderloo SE, McAlister FA. Comparative safety and effectiveness of metformin in patients with diabetes mellitus and heart failure: Systematic review of observational studies involving 34,000 patients. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):395–402. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA, Salpeter Posthumous EE. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD002967. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002967.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •51.Cittadini A, Napoli R, Monti MG, Rea D, Longobardi S, Netti PA, Walser M, Sama M, Aimaretti G, Isgaard J, et al. Metformin prevents the development of chronic heart failure in the shhf rat model. Diabetes. 2012;61(4):944–953. doi: 10.2337/db11-1132. Longitudinal animal study where rats with hypertensive heart disease were treated with metformin and rosiglitazone. Metformin was associated with improved cardiac outcomes and decreased progression to heart failure. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong AK, Symon R, AlZadjali MA, Ang DS, Ogston S, Choy A, Petrie JR, Struthers AD, Lang CC. The effect of metformin on insulin resistance and exercise parameters in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(11):1303–1310. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Braunwald E, Bristow MR. Congestive heart failure: Fifty years of progress. Circulation. 2000;102(20 Suppl 4):IV14–23. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_4.iv-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Algahim MF, Sen S, Taegtmeyer H. Bariatric surgery to unload the stressed heart: A metabolic hypothesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302(8):H1539–1545. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00626.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lavie CJ, Alpert MA, Arena R, Mehra MR, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Impact of obesity and the obesity paradox on prevalence and prognosis in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2013;1(2):93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]