Abstract

Over the past three decades, the goal of many researchers is analysis of exhaled breath condensate (EBC) as noninvasively obtained sample. A total quality in laboratory diagnostic processes in EBC analysis was investigated: pre-analytical (formation, collection, storage of EBC), analytical (sensitivity of applied methods, standardization) and post-analytical (interpretation of results) phases. EBC analysis is still used as a research tool. Limitations referred to pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical phases of EBC analysis are numerous, e.g. low concentrations of EBC constituents, single-analyte methods lack in sensitivity, and multi-analyte has not been fully explored, and reference values are not established. When all, pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical requirements are met, EBC biomarkers as well as biomarker patterns can be selected and EBC analysis can hopefully be used in clinical practice, in both, the diagnosis and in the longitudinal follow-up of patients, resulting in better outcome of disease.

Keywords: exhaled breath condensate, analysis, preanalytical phase, respiratory diseases

Introduction

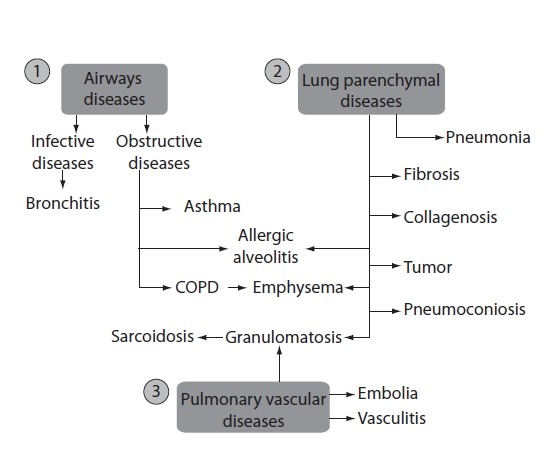

The main function of the lungs is respiratory function, i.e. respiratory gas exchange. In addition, the lungs have other important non-respiratory functions. The latter include the maintenance of a stable acid-base balance, immunological functions and metabolic activities. Respiratory diseases are the most common diseases in children and adolescents (e.g. allergic diseases, infections of respiratory system) and adults (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD). Generally, respiratory diseases include three main groups: airways diseases, lung parenchymal diseases and pulmonary vascular diseases (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Respiratory diseases: airways diseases (1), lung parenchymal diseases (2) and pulmonary vascular diseases (3). COPD - chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

In some diseases, there is overlap between pathological hallmarks, e.g. allergic alveolitis and emphysema are airways and lung parenchymal diseases; granulomatosis is both, lung parenchymal and pulmonary vascular disease. In industrialized countries, the morbidity of infectious diseases are decreasing, and morbidity of obstructive diseases, particularly asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have been increasing in the past century (1).

The diagnosis of respiratory diseases and the evaluation of therapeutic outcome are based on history data, clinical symptoms, pulmonary function testing and imaging techniques. In addition, for direct assessment of inflammation invasive procedures to obtain bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), biopsy specimens, induced sputum are used in everyday practice. However, these procedures are used when strongly indicated, especially in young children (2,3). Therefore, over the past three decades, the goal of many researchers has been to approve analysis of breath and exhaled breath condensate (EBC) as noninvasively obtained samples (2,3).

More than 30 years ago, Sidorenko et al. in the former Soviet Union started with the analysis of EBC, and the first article was published in Russian language in 1980 (4). Over the next decade, only Russian scientists have supported the idea that EBC may be a promising matrix for the diagnosis of lung diseases. From 1992, after Western researches published their first EBC paper (5), the number of published articles has been increasing progressively. During the period from 1980 to 2012, databases PubMed, OVID and Scopus have so far included 869, 917 and 3628 published articles on EBC, respectively. The following authors have investigated EBC systematically and have published more than 10 articles in the field: Montuschi P. (76 articles), Barnes PJ. (60 articles), Corradi M. (49 articles), Kharitonov SA. (39 articles), Carpagnano GE. (38 articles), Horvath I. (34 articles), Mutti A. (27 articles), Hunt J. (23 articles), Antus B. (16 articles), Antczak A. (14 articles), Effros RM. (13 articles), Kostikas K. (13 articles), Rosias PP. (11 articles) and their colleagues. In Croatia, two groups of researchers made a modest contribution to the investigation of EBC analysis: authors from Srebrnjak Children Hospital, Zagreb (Dodig S, et al., analysis of EBC in children, 9 articles) and authors from Institute for Medical Research and Occupational Health, Zagreb (Ljubičić Ćalušić A, et al., analysis of EBC in adults, 3 articles). Many papers pay attention to the problems in EBC determination (both, clinical and analytical problems). If analytical problems are not solved, conclusions based on clinical investigations will be uncertain. Therefore, the aim of the present review was to accentuate some analytical problems in EBC analysis.

Clinical laboratory specialists should assume responsibility for the total analytical process (total testing cycle) in laboratory medicine, from the patient preparation, test selection, leading to sample collection, transport to the laboratory, sample handling and storage, sample analysis and finally, results report. These activities are classified into three phases - preanalytical, analytical and postanalytical. This paper gives a review of some solved and unsolved problems typical for the total testing cycle of EBC.

Preanalytical phase of EBC analysis

Laboratory professionals are aware that preanalytical phase in laboratory medicine is a very important component of laboratory testing (6,7). In the last two decades, a great attention was paid to define preanalytical issues in EBC analysis – from formation, sampling, sample handling, environmental factors, and dilution to appropriate handling and storage (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical phases of exhaled breath condenste analysis.

| Phase | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Preanalytical | ||

|

| ||

| Formation | 7–16 | |

|

| ||

| Collection | 17, 18 | |

| Sample handling | Environmental temperature and relative humidity | 19–22 |

| Condenser temperature | 18 | |

| Collection time | 17 | |

| Collection volume | 17, 19, 24 | |

| Dilution | 25–26 | |

| Sample contamination | 27–29 | |

| Pre-analytical procedures | ||

| Gas standardization | 30–35 | |

| Isolation / extraction / lyophylization | 17, 36–42 | |

| Storage | 17, 34 | |

|

| ||

| Analytical | ||

|

| ||

| Methods selection | ||

|

| ||

| Single-analyte determination | 43–46 | |

| pH-metry | 2, 3, 19, 43 | |

| spectrophotometry | 44, 45 | |

| spectrofluorometry | 46, 52 | |

| enzymatic assay | ||

| ELISA | 2, 3 | |

| fluoroimmunoassay | 2, 3 | |

| radioimmunoassay | 2, 3 | |

|

| ||

| Multi-analyte determination | ||

| 2-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis | 4 | |

| immunoassays | 2 | |

| GC, MS, HPLC | 48 | |

| GC-MS, LC-MS, HPLC-MS | 39, 49, 50 | |

| DMS, GC-DMS, ESI-DMS | 51, 56 | |

|

| ||

| Method standardization | ||

| optimization, validation | 57 | |

| lower limit of detection and quantification | 58 | |

| lower limit of detection and quantification | 26 | |

|

| ||

| Post-analytical | ||

|

| ||

| Reference values | NA, 79 | |

|

| ||

| Clinical use and interpretation | ||

|

| ||

| Biomarker selection - Diagnose and monitoring | ||

| asthma | 17, 44, 60, 69, 73, 74, 89, 90, 95 | |

| COPD | 42, 47, 54, 71–73, 77, 83, 86, 96 | |

| CF | 7, 17, 76, 92 | |

| OSA | 80, 94 | |

| GERD | 2, 3, 45 | |

| ARDS | 17, 93 | |

| lung cancer | 3, 97 | |

| non-respiratory diseases | 82, 84 | |

ELISA – enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GC – gas chromatography; MS - mass spectrometry; HPLC - high performance liquid chromatography; GC-MS - gas chromatography-mass spectrometry; LC-MS - mass spectrometry; HPLC-MS - high performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry; DMS - differential mobility spectrometry; GC-DMS - mass spectrometry-differential mobility spectrometry; ESI-DMS - electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry-differential mobility spectrometry; COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CF - cystic fibrosis; OSA -obstructive sleep apnea; GERD – gastroesophageal reflux disease; ARDS - acute respiratory distress syndrome; NA – not available.

Formation of EBC

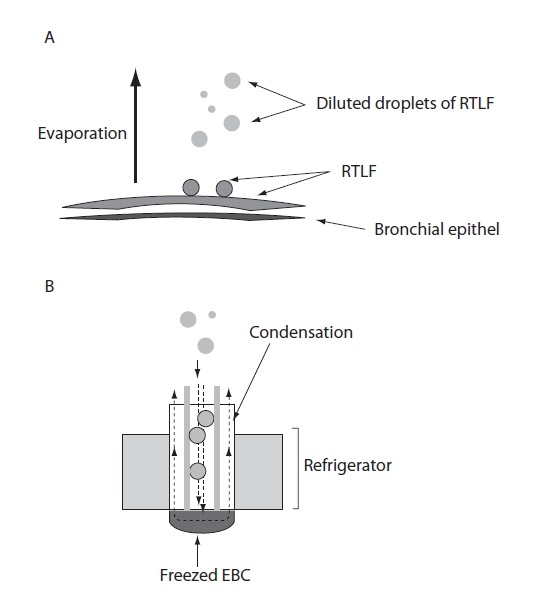

Exhaled breath contains thousands of volatile (such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, nitric oxide, ethane, pentane) and non-volatile compounds, water vapour as well as liquid particles (i.e. droplets) and bioaerosols (bacteria, viruses, fungi) that derive from the respiratory tract (8,9). Droplets of respiratory tract lining fluid (RTLF) are released from the surfaces of the airways (Figure 2A). In addition, a great quantity of water is released as vapour (evaporation). During turbulence in the airways, i.e. during reopening of closed bronchioles and alveoli, non-volatile compound from epithelial lining fluid undergoes aerosolization (3,10). The droplet formation depends on the velocity of the flow of exhaled air and the surface tension (higher velocity/lower surface tension). The number of particles in exhaled air is very low, ranging from 0.1 – 4 particles × cm−3 (diameter < 0.3 μm) (11).

FIGURE 2.

Formation of exhaled breath (A) and sampling of EBC in the cooled container (B): A – Droplets of respiratory tract lining fluid (RTLF) are released from the surfaces of the airways. A great quantity of water are released as vapor (evaporation); B – When droplets of RTLF reach the condenser, they become diluted by water vapor that are deposited on the walls of the refrigerated container (condenser).

RTLF is a thin liquid film that lines the respiratory epithelium. Its composition varies between conducting zone (airways) and the respiratory zone (respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveoli) (12). RTLF in the conducting zone consists of two phases: sol phase (watery) and gel phase (mucus). The sol phase contains soluble components of bronchial secretion and serum proteins, while gel phase contains bronchial glycoproteins, protein bound to the bronchial glycoproteins and some serum proteins (13). RTLF in the respiratory zone (surfactant) contains phospholipids (80%), cholesterol (10%), proteins (10%), and very small amounts of carbohydrates (12). EBC composition corresponds to the composition of RTLF, but in significantly lower concentrations (14). According to Effros et al., EBC consists of water vapour, and contains aerosol particles originating from the RTLF from the lower airways (15). However, according to Bondesson et al. (16), EBC derives mainly from the central airways, and its content may not correspond to the content of RTLF originating from smaller airways. Therefore, the exact anatomical site of origin and the precise mechanism of EBC formation are still a matter of dispute.

Collection of EBC

Optimized collectors for EBC sampling are available from various manufacturers, all based on the principle of “freezing exhaled breath” (Figure 2B). According to the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) Task Force on recommendations for EBC (17) collectors should have an inert material on the condensing surface, e.g. glass, silicone, teflon, aluminium, polypropylene. There is no ideal device for collecting EBC for all biomarkers, since the concentrations of some biomarkers depend on adhesive properties of condenser coatings. The subject breathes calmly (tidal breath, respiratory rate 15–20 breaths/minute) via a mouth-piece (with nasal clip) connected to a tube that separates inhaled and exhaled air. During exhalation, the air passes through a condenser cooled to a low temperature (−5 °C to −30 °C for different manufacturers; usually at −20 °C), and EBC is collected in the cooled container (e.g. electric refrigerator) (3). Condensing temperature affects significantly the pH-values of EBC (pH is more acidic at condensing temperature −70 °C, than at −20 °C) (18). Therefore, the condensation temperature has to be reported to facilitate comparison of results obtained by different laboratories (3). In addition, levels of some biomarkers (e.g. oxidative stress markers) have shown circadian variations. Hence, the time of EBC collection should be recorded. Determination of biomarkers known to be affected by certain food, drinks or medications it is recommended to abstain from these a few hours before EBC collection (Figure 2) (3,17).

Influence of environmental temperature and relative humidity

Environmental conditions, i.e. relative humidity (RH) and temperature may influence on the volume of EBC and on the determination of some constituents in EBC sample (pH-values). Smaller volume may be obtained at lower RH (19). RH of inspired air influences the rate at which EBC is formed (20) and the diameter of an expired droplet (21). The diameter of exhaled particles is smaller and supersaturated at lower ambient RH. Ambient temperature affects significantly the pH-values of EBC. pH is more acidic at 23 °C than at 37 °C (22). Therefore ambient temperature RH have to be under control in the room, where the EBC is collected.

Collection time of EBC

Ventilatory rate is the major determinant of the amount of EBC over time. With respiratory rate of 15–20 breaths/minute, sufficient sample may be collected during 10–15 minutes (i.e. 150–300 breat hs).

Volume of EBC

A strong positive correlation was found between EBC volume and total respired volume and tidal volume, respectively (23). Volume of collected EBC does not depend on lung function parameters, e.g. forces expiratory volume in 1 second, (FEV1). As the amount of EBC increases significantly with higher minute ventilation (19), the volume of EBC varies among individuals. According to Lema et al. (24) the relation between the volume of inhaled air and the volume of collected EBC for each subject is expressed by the equation:

If respiratory rate remains constant during EBC collection, EBC volume increases linearly with the time of collection. Approximately 1–2 mL of EBC may be collected during the period of about 10 minutes (from 40 to 300 mL/min, average ∼100 mL/min) (17).

Dilution of EBC

EBC contains droplet with large amounts of water vapour and traces of non-volatile solutes. Dilution of EBC is much greater than dilution of RTLF (25), since RTLF is diluting during condensation (Figure 2B). Although some methods have been developed to estimate the degree of EBC dilution, i.e. determination of urea, total cation concentration and of conductivity of lyophilized EBC (26), the exact degree of EBC dilution is still unknown. According to Effros, non-volatile constituents are diluted about 1:12,000 (26)

Contamination of EBC

Contamination of EBC occurs due to possible saliva and oropharingeal content leaking into the sample. Prevention of salivary contamination may be achieved by the use of EBC collectors with a mouthpiece and a two-way non-rebreathing valve. As saliva contains many specific biomarkers (proteins, lipids, carbohydrates), appropriate measures to prevent its leaking into EBC must be applied (collector selection, periodic swallowing of saliva during collection) (27). Determination of amylase catalytic concentration in EBC is used to determine the extent of salivary contamination and for rejection of unsuitable specimens of EBC. Bacterial flora from pharingo-oral tract may increase nitrite concentration in EBC (28). Bacterial contamination should be prevented by mouthwash with chlorhexadine before EBC collection.

Recently, fractionation of exhaled breath was used to reduce the contribution of upper airways (influence of environmental factors on upper airways) and to increase the contribution of bronchial and alveolar tracts on the EBC content, e.g. malondialdehyde (29).

Sample handling - pre-analytical procedures

Gas standardization of EBC

The value of pH is not stable due to the effect of the atmosphere and exhaled CO2. On gas standardization, i.e. deareation CO2 is removed from the sample, thus reducing the effect of CO2 on pH measurement (30). Gas standardization may be performed in more ways, e.g. by bubbling argon, partial CO2 pressure of 5.33 kPa and helium through the EBC samples. pH can be determined in EBC before (31) or after gas standardization (32). On each inspiration at rest, 10% of air in the lungs is exchanged by atmosphere air (33), where pO2 = 21 kPa and pCO2 = 0. The content of CO2 and O2 is different in lungs and in atmosphere. pO2 in the inspired air is about 20 kPa and in the alveoles about 14.7 kPa, whereas pCO2 in the alveoles is about 5.3 kPa. In the exhaled air, pO2 is about 15.9 kPa and pCO2 is about 4.2 kPa (33). During the procedure of gas standardization of EBC, pH rises to a point at which stable reading is possible. In healthy individuals, pH of gas standardized EBC ranges between 7.4 and 8.8 (34), and in asthmatics pH ranges between 7.58 and 7.75 before therapy and between 7.67 and 7.91 after the therapy with salbutamol, respectively (35).

Extraction methods for some analytes from EBC

For chromatographic methods of some analytes in EBC (e.g. leukotrienes), their extraction/concentration is required. These procedures increase analytical sensitivity in the determination of analytes in EBC. These methods include immunoaffinity extraction, IAE (36), solid phase extraction, SPE (37), solvent extraction, SE (38) and lyophylization (39). IAE include separation of compounds with specific antibodies. By the SPE dissolved or suspended compounds are separated from other compounds in the liquid mixture based to their chemical and physical properties. SE is used to separate components according to their relative solubility in water and organic solvent. These extraction methods are performed for sample purification prior to chromatography analysis. Consequently, they reduce interferents from the EBC matrix that can influence the result. Lyophilization, also known as freeze drying process of dehydratation, may be used for concentrating non-volatile or semi-volatile compounds dissolved in EBC (39). In that way, EBC may be stored without refrigeration for long period (40). In addition, process of EBC lyophilisation removes volatile solutes, e.g. NH3(41), which may influence pH or conductivity of EBC. An EBC sample lyophilized and then resuspended gives a 20-fold concentration of biomarkers (42). Lyophilisation may improve reproducibility in determination of some biomarkers (17).

EBC storage

Although EBC can be analyzed immediately after collection, samples are usually stored at low temperature until analysis (17), since some EBC constituents (H2O2, pH) are instable at room temperature. EBC can be stored at different freezing temperatures, i.e. from −20 °C (34) to −80 °C (17). However, freeze-thaw cycles should be avoided (2,3).

Analytical phase

Analytical methods

Apart from preanalytical issues of EBC, its analysis is very important methodological issue, because conventional assays must be adjusted to very low concentrations of biomarkers in EBC. The problem is more conspicuous in immunoassays, especially in commercial immunoassay kits, that neither are not validated for such low concentrations nor for the matrix of EBC sample (27). So, these conventional methods are affected by poor sensitivity and specificity.

Usually, methods for the analysis of EBC samples were traditional analytical methods for the analysis of other biological samples, and these methods are scheduled for the single-analyte determination, e.g. pH-metry, biosensors (43), spectrophotometry (44,45), spectrofluorimetry (46), enzymatic assay (47), immunoassays (ELISA, immunoluminometry, radioimmunoassay – RIA, immunosensors) (2). Immunoassays need to be validated with reference analytical methods such as mass spectrometry or high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), that enable a precise determination of the concentrations of the different markers in EBC (4) (Table 1).

Recently, multi-analyte methods were introduced for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of EBC. These methods include two-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis (2-D PGE) (4) and micro-analysis of protein spots by chromatography. Chromatography methods are gas chromatography (GC), high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), mass spectrometry (MS), liquid chromatography – mass spectrometry (LC-MS), gas chromatography – mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (48), high performance liquid chromatography – tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) (49), multi-parameter chemical sensors, i.e. chromatography differential mobility spectrometry (GC/DMS) (50), electrospray ionization differential mobility spectrometry (ESI/DMS) (51). All these multi-analyte methods make it possible to recognize parlar components in nanomolar concentrations. However, contaminations (even in nanograms) may cause different results.

Unfortunately, despite numerous investigations, analysis of EBC has limitations regarding optimization and validation of quantitative analytical procedures. Therefore, it is not possible to make a comparison of results from different laboratories (46). Determination of nitric oxide (NO) metabolites is based on spectrophotometric methods (2). H2O2 is measured spectrophotometrically, spectrofluorimetrically (52) or by the use of an automated amperometric biosensor (53). Eicosanoids in EBC are measured by different techniques, including immunoassays, chromatography and mass spectrometry; the latter method is considered as reference method (2). So, isoprostanes may be determined by using GC-MS; prostanoids by RP-HPLC (reversed phase-high performance liquid chromatography) and GC-M. For determination of leukotrienes HPLC or LC-MS may be recommended. LCMS is considered as the ‘gold standard’ method for simultaneous determination of different isoprostanes (39). In addition, LC-MS is an ideal for the simultaneous determination of various purines (54). Methods for the determination of proteins in EBC depend on the concentration of the particular protein in EBC. Hence, total proteins may be measured spectrophotometrically (19), cytokines by using enzyme immunoassay 2-D PGE (4) and cytokeratins and other proteins present in nanomolar concentration by the use of HPLC-MS (55). Although pH-value was measured with different pH-electrodes or biosensors, Ross-type pH electrodes should be used for the determination of pH in EBC (45), since the EBC matrix has low ionic strength.

Recently, so called “omic science”, especially metabolomics and metabonomics, were introduced in the analysis of EBC. Metabolomics enables to look at genotype-phenotype relationships and genotype-envirotype relationship. Metabonomics may identify and quantify the metabolic fingerprint of EBC in different clinical sets of data. The methods that are used in metabolomic/metabonomic analysis are MS (detection in femtomoles), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) based spectroscopy (detection in micromoles) (56).

Method optimization/validation

Optimization and validation of conventional methods applied for EBC analysis are problematic, especially for the very low concentrations of biomarkers, since the coefficient of variations (CV) is much higher due to nonlinearity of the assay in that low range (57). All results in the low range are based on interpolation, and the determination of the lower limit of detection (LOD) and lower limit of quantification (LOQ) are disputable. In addition, validation of analytical methods for EBC analysis depends on the standardization of preanalytical phase. Analysis of EBC by using conventional analytical methods is more useful for qualitative than for quantitative analysis of EBC (46). Immunoassays are sensitive, but lack in specificity. Conventional techniques must be compared with reference methods, i.e. chromatographic techniques and mass spectrometry, methods that have satisfactory precision, accuracy, LODs, LOQs (58).

Limit of detection and quantification for analytes in EBC

LOD defines the lowest quantity of a substance that can be distinguished from the blank value (zero, absence of particular substance) in the linear range of the assay, where the value of CV is known. LOQ presents the lowest quantity of the substance that can be measured. It is not easy to define the LODs and LOQs of EBC constituents, since native EBC sample is extremely diluted solution and most biomarkers are present at very low concentrations. Therefore, LODs and LOQs of EBC constituents depend on the pre-treatment procedures of EBC (preconcentration, i.e. lyophilisation). EBC preconcentration is necessary to improve LODs and LOQs values. In addition, LOD of particular component depends on the method used to determine its value (Table 2). In general, spectrophotometric methods and immunoassays have higher detection limits (detection at micromolar levels) than the chromatographic methods (detection at nanomolar and picomolar levels) (Table 2) (3,55).

TABLE 2.

Detection limits for some analytes in exhaled breath condensate (19).

| Analyte | Detection limit | Method |

|---|---|---|

| Hxdrogen peroxide | 0.1 μmol/L | Spectrofluorimetry |

| Nitrate/nitrite | 0.1 μmol/L | Spectrofluorimetry |

| Leukotriene LTB4 | 4.4 ng/L | Enzyme immunoassay |

| 8-isoprostane | 3.9 ng/L | Enzyme immunoassay |

| Adenosine | 2 nmol/L | High performance liquid chromatography |

Data handling

Normalization factor for analytes in EBC

To account for the fluctuation of constituents in extremely diluted biological samples, laboratory medicine specialists try to normalize (i.e. adjust) the level of particular analyte using the marker with stable concentration. A normalization factor is defined as the ratio between two analytes in the same body fluid. Some authors (26) have tried to develop normalization factor, e.g. concentration of urea, cation concentration and osmolality and conductivity after lyophilisation. As the normalization factor must have the same physical and chemical characteristics (solubility, volatility) as the measured constituent, a universal normalization factor is not yet defined (59,60). Urea might be the normalization factor to control intra-individual variability of different analytes in EBC samples (59,60).

Post-analytical phase

EBC is a matrix that contains large number of mediators that can be used as biomarkers of respiratory diseases. Biochemical biomarkers in EBC are indicators of health condition or indicators of a pathogenic biological process in respiratory system, particularly in lower respiratory tract. The interpretation of the values of the particular biomarker or biomarkers pattern in EBC samples is the final goal of EBC analysis. Laboratory medicine specialists and clinicians have to co-operate in this field of science. Values of EBC constituents have been extensively investigated in healthy subjects as well as in patients with respiratory diseases, since these diseases are associated with alterations of the RTLF composition (59). The majority of investigations refer to H2O2(2,3,17,59), pH (2,3,19,30,61), nitric oxide (NO) (2,3,19) and its metabolites (2,3,62,63), purines (3,64,65), various eicosanoides (prostanoides, leukotrienes) (2,3,66) and proteins (interleukins, cytokines, cytokeratins) (42,67), electrolytes (68), urates (69). Special issue is referred on mebolomics, i.e. the analysis of multi-parametric metabolic data (56). For some biomarkers, values are determined for healthy subjects, and some of them are shown in Table 3 (H2O2(17,60), pH (34,43,46,70), 8-isoprostane (71–73) malondialdehyde (74, 75), IL-6 (76), nitrite (77, 78).

TABLE 3.

Concentration of biomarkers in exhaled breath condensate in healthy adults and children.

| Analyte | Values | References |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen peroxide (μmol/L) | ||

| Adults, range | 0–0.9 | 17 |

| Children, M(IQR) | 0.045 (0.017–0.082) | 60 |

|

| ||

| pH | ||

| Adults, mean ± SD | 7.70 ± 0.49 | 34 |

| Adults, mean ± SD | 7.85 ± 0.02 | 70 |

| Adults, M (IQR) | 7.72 (7.63–7.76) | 43 |

| Children, mean ± SD | 7.05 ± 0.35 | 45 |

|

| ||

| 8-isoprostane (ng/L) | ||

| Adults, mean ± SD | 6.2 ± 0.4 | 71 |

| Adults, mean ± SD | 4.7 ± 1.8 | 72 |

| Children, mean ± SD | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 73 |

|

| ||

| Malondialdehyde (nmol/L) | ||

| Adults, M (IQR) | 15.6 (4–25) | 75 |

| Children, mean ± SD | 19.4 ± 1.9 | 74 |

|

| ||

| IL-6 (ng/L) | ||

| Adults, mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 73 |

| Children, mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 76 |

|

| ||

| Nitrite (μmol/L) | ||

| Adults, M (IQR) | 2.9 (1.6–5.3) | 77 |

| Children, M (IQR) | 0.41 (0.13–1.83) | 78 |

M – median; IQR – interquartile range; SD – standard deviation; IL – interleukin.

Reference values for key biomarkers in EBC

Determination of reference values of particular analytes in EBC and selection of different disease-related biochemical biomarkers are integral part of post-analytical phase of the EBC analysis (Table 1, Table 3). However, reference values for EBC constituents are not established, since some analytical problems are not solved. Concentrations of some biomarkers in EBC obtained in healthy subjects, adults and children, are presented in Table 3. These values derived from the literature data in investigations of biomarkers in patients with respiratory diseases, where healthy subjects had participated as control groups. Future studies are needed to establish the reference values of EBC biomarkers (79).

Clinical use and interpretation of biomarkers in respiratory diseases

A number of investigations study the changes of biomarkers in different pulmonary diseases (Table 1, Table 4). The list of states and diseases for which EBC analysis is used include asthma (2,3,17,44,69,73, 74,77,89,90,95), COPD (2,3,42,47,54,71–73,77,83,86, 96), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (2,3,45), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) (80,94), pulmonary fibrosis (81), pneumonia (4,17), cystic fibrosis (7,17,76,92), adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (3,17,93), non-respiratory diseases (82,84) (Table 1).

TABLE 4.

Biomarkers in EBC in relationship with clinical studies (adapted according to reference 4).

| Comparison with healthy subjects | Correlation with | After treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen peroxide | |||

| acute asthma | ↑ | Positive with sputum eosinophils | ↓ |

| COPD | ↑ | Positive with sputum neutrophils | ↓ |

| CF | ↔ | NA | ↓ |

|

| |||

| pH | |||

| acute asthma | ↓ | Inverse with FEV1 | ↑ |

| COPD | ↓ | NA | ↑ |

| CF | ↓ | NA | ↑ |

| Bronchiectasis | ↓ | NA | ↔ |

| GERD | ↔ | NA | ↔ |

| OSA | ↓ | NA | NA |

|

| |||

| Adenosine | |||

| acute asthma | ↑ | Asthma severity, FeNO | NA |

| COPD | ↔ | NA | NA |

| CF | ↔ | NA | NA |

|

| |||

| Adenosine/urea | |||

| acute asthma | ↑ | NA | NA |

| COPD | ↑ | COPD severity, Inverse with FEV1 | ↓ |

| CF | ↑ | Inverse with FEV1 | ↔ |

|

| |||

| 8-isoprostane | |||

| acute asthma | ↑ | NA | Resistant |

| COPD | ↑ | NA | ↓ |

|

| |||

| Nitrite/nitrate | |||

| acute asthma | ↑ | Inverse with FEV1 | ↓ |

| COPD | ↑ | Inverse with FEV1 | NA |

|

| |||

| IL-4 | ↑ | ||

| acute asthma | NA | ↓ | |

|

| |||

| IL-6 | |||

| acute asthma | ↑ | NA | NA |

| COPD | ↑ | NA | NA |

| GER | ↑ | NA | NA |

COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CF – cystic fibrosis; GER – gastroesophageal reflux; GERD – gastroesophageal reflux disease; FeNO – fractional exhaled nitric oxide; FEV1 – forced exhaled volume in 1 second;↑ – increased, ↓ – decreased, ↔ – no difference, not detectable or absence; NA – not available.

Increased values of H2O2 in EBC were found in healthy smokers (17), in patients with asthma (19,60), COPD (17,93), cystic fibrosis (7) bronchiectasis (17), ARDS (17), as well as in non-respiratory disease, e.g. systemic sclerosis (84). In addition, day to day intra-subject CV of 43% in healthy subjects has been reported (85).

Significant decrease in EBC pH has been reported in patients with acute exacerbation of asthma (17) and in COPD (86). The term ‘acid stress’ describes a shift in pH toward the more acid values (87). In asthmatics, pH returned back higher values after successful anti-inflammatory treatment with steroids (17,60). Furthermore, pH levels were related to eosinophilic (in asthmatics) or neutrophilic (in patients with COPD) inflammation of the airways (19).

Concentrations of NO and NO-related compounds were found to be significantly higher in asthma (63). In patients with COPD, literature data of nitrite/nitrate levels are not consistent. Some studies have indicated increased levels (88), and some studies reported unchanged levels of nitrite/nitrate in comparison with healthy controls (62). Children with CF are reported to have decreased levels of NO and increased levels of nitrite in EBC (63). It seems that NO production in these patients is trapped by mucus in the airways. Therefore, the determination of nitrite might be a better biomarker of NO production in patients with CF.

Leukotrienes, Cys-LTs and LTB4, were reported to be increased in asthmatic patients as compared with healthy subjects (89). Prostaglandine PGE2 levels were found to be increased in EBC in patients with COPD (83). In these patients, LTB4 increased in the stable state. During exacerbation, the concentration of LTB4 was markedly higher than in the stable phase of disease, and after antibiotic treatment LTB4 levels were decreased (71). In patients with CF concentration of LTB4 were increased (76).

8-isoprostane concentration was found to be elevated in asthma (90), COPD (83), interstitial lung disease (91), CF (92), ARDS (93), OSA (94). In patients with acute exacerbation of asthma or COPD, 8-isoprostane concentrations were found to be decreased after anti-inflammatory medications (17).

Concentrations of interleukins are changed in some pulmonary diseases in comparison with healthy subjects, e.g. IL-4 levels were increased, and interferon-γ levels were decreased in ascthmatic subjects (95). Furthermore, medication with steroids resulted with decrease of IL-4 and increase of interferon-γ concentration. Concentrations of IL-6 were increased in patients with OSA (94), COPD (96), CF (76), lung cancer patients (97), and in cigarette smokers (98) (Table 4).

Outlook

We must be aware that EBC analysis is still used as a research tool only. Limitations referred to pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical phases of EBC analysis are numerous. The major limitation is enormous dilution of the RTLF, and consequently, low concentrations of EBC constituents, with detection levels close to the limits of analytical methods. Furthermore, methods for single-analyte determinations lack in sensitivity. Today, the interpretation of the results obtained is somewhat doubtful since reference values are not established. Therefore, research and standardization of all the phases of the analytical process should be continued to allow appropriate interpretation of the results obtained. The application of multi-analyte EBC analysis in the field of metabonomics, proteomics, and genomics (99,100) has not been fully explored. Metabolomic/metabonomic based analyses of EBC have shown the possibility to discriminate between healthy and asthmatic subject, and furthermore to characterize asthma sub-phenotypes. Some efforts are made to investigate DNA as a biomarker for lung diseases (2). However, the results are dissonant, since some authors have detected DNA, and some authors failed to detect DNA in EBC. Our attempt to detect DNA in EBC was unsuccessful, too.

Hopefully, when all pre-analytical, analytical and post-analytical requirements are met, EBC biomarkers can be selected, and EBC analysis can be used in clinical practice, in the diagnosis and, even in the longitudinal follow-up of patients (monitorig of therapy effects), resulting in better outcome of disease.

Acknowledgments

The results presented were obtained in the scope of a scientific project 277-2770966-0965, entitled Exhaled Breath Condensate as a Source of Lung Disease Biomarkers in Children, carried out with support from the Ministry of Science, Education and Sports of the Republic of Croatia.

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Burney P. Respiratory disease. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22:107–11. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montuschi P, editor. New perspectives in monitoring lung inflammation Analysis of exhaled breath condcensate. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2005. pp. 1–218. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horvath I, de Jongste JC, editors. Exhaled biomarkers. Eur Respir Mon. 2010;49:1–249. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sidorenko GI, Zborovskiĭ EI, Levina DI. Surface-active properties of exhaled air condensate (a new method of studying lung function. Ter Arkh. 1980;52:65–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson WC, Swetland JF, Benumof JL, Laborde P, Taylor R. General anesthesia and exhaled breath hydrogen peroxide. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:703–10. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199205000-00007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simundic AM, Lippi G. Preanalytical phase – a continuous challenge for laboratory professionals. Biochem Med. 2012;22:145–9. doi: 10.11613/bm.2012.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.11613/BM.2012.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lippi G, Becan-McBride K, Behúlová D, Bowen RA, Church S, Delanghe J, et al. Preanalytical quality improvement: in quality we trust. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51:229–41. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0597. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2012-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robroeks CM, van Berkel JJ, Dallinga JW, Jobsis Q, Zimmermann LJ, Hendriks HJ, et al. Metabolomics of volatile organic compounds in cystic fibrosis patients and controls. Pediatr Res. 2010;68:75–80. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181df4ea0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181df4ea0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDevitt JJ, Koutrakis P, Ferguson ST, Wolfson JM, Fabian MP, Martins M, et al. Development and performance evaluation of an exhaled-breath bioaerosol collector for influenza virus. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2013;47:444–51. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2012.762973. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2012.762973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society ATS/ERS recommendations for standardised procedures for the online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:912–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-710ST. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200406-710ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fairchild CI, Stampfer JF. Particle concentration in exhaled breath. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1987;48:948–9. doi: 10.1080/15298668791385868. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15298668791385868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng AW, Bidani A, Herring TA. Innate host defense of the lung: Effects of lung-lining fluid pH. Lung. 2004;182:297–317. doi: 10.1007/s00408-004-2511-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00408-004-2511-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim WD. Lung mucus: A clinician’s view. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1914–17. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10081914. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.97.10081914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt J. Exhaled breath condensate: an evolving tool for noninvasive evaluation of lung disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:28–34. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.124966. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/mai.2002.124966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Effros RM, Biller J, Foss B, Hoagland K, Dunning MB, Castillo B, et al. A simple method for estimating respiratory solute dilution in exhaled breath condensate. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1500–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200307-920OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200307-920OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bondesson E, Jansson LT, Bengtsson T, Wollmer P. Exhaled breath condensate – site and mechanisms of formation. J Breath Res. 2009;3:1–5. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/3/1/016005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1752-7155/3/1/016005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horvath I, Hunt J, Barnes PJ, On behalf of the ATS/ERS Task Force on Exhaled Breath Condensate Exhaled breath condensate: Methodological recommendations and unresolved questions. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:523–48. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00029705. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00029705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Czebe K, Barta I, Antus B, Vaylon M, Horváth I, Kullman T. Influence of condensing equipment and temperature on exhaled breath condensate pH, total protein and leukotriene concentrations. Respir Med. 2008;102:720–5. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.12.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCafferty JB, Bradshaw TA, Tate S, Greening AP, Innes JA. Effects of breathing pattern and inspired air conditions on breath condensate volume, pH, nitrite, and protein concentrations. Thorax. 2004;59:694–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.016949. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2003.016949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mutlu GM, Garey KW, Robbins RA, Danziger LH, Rubinstein I. Collection and analysis of exhaled breath condensate in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:731–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2101032. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2101032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmgren H, Bake B, Olin A-C, Ljungström E. Relation between humidity and size of exhaled particles. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2011;24:253–60. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2011.0880. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jamp.2011.0880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koczulla AR, Noeske S, Herr C, Dette F, Pinkenburg O, Schmid S, et al. R. Ambient temperature impacts on pH of exhaled breath condensate. Respirology. 2010;15:155–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01664.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Thomas PS. Relationship between exhaled breath condensate volume and measurements of lung volumes. Respiration. 2007;74:142–5. doi: 10.1159/000094238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000094238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lema JBD, González M, Vigil L, Casan P. Exhaled breath condensate: standardized collection of samples from healthy volunteer. Arch Bronconeumol. 2005;41:584–6. doi: 10.1016/s1579-2129(06)60287-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1579-2129(06)60287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Čepelak I, Dodig S. Exhaled breath condensate: A new method for lung disease diagnosis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:945–52. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.326. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/CCLM.2007.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Effros RM, Dunning MB, III, Biller J, Shaker R. The promise and perils of exhaled breath condensate. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:1037–80. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00069.2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00069.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosias PP. Methodoligical aspects of exhaled breath condensate collection and analysis. J Breath Res. 2012;6:027102. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/6/2/027102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1752-7155/6/2/027102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zetterquist W, Marteus H, Kalm-Stephens P, Näs E, Nordvall L, Johannesson M, et al. Oral bacteria--the missing link to ambiguous findings of exhaled nitrogen oxides in cystic fibrosis. Respir Med. 2009;103:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.09.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldoni M, Corradi M, Mozzoni P, Folesani G, Alinovi R, Pinelli S, et al. Concentration of exhaled breath condensate biomarkers after fractionated collection based on exhaled CO2 signal. J Breath Res. 2013;7:017101. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/7/1/017101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1752-7155/7/1/017101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kullman T, Barta I, Lazar Z, Szili B, Barat E, Valyon M, et al. Exhaled breath condensate pH standardised for CO2 partial pressure. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:496–501. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00084006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00084006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ojoo JC, Mulernnan SA, Kastelik JA, Morice AH, Redington AE. Exhaled breath condensate pH and exhaled nitric oxide in allergic asthma and cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2005;60:22–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.017327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2003.017327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ATS Workshop Proceedings Exhaled breath condensate nitric oxide and nitric oxide oxidative metabolism in exhaled breath condensate. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:131–45. doi: 10.1513/pats.200406-710ST. http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/pats.200406-710ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Treacher DF, Leach RM. ABC of oxygen. Oxygen transport. 1. Basic principles. BMJ. 1998;317:1302–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaughan J, Ngamtrakulpanit L, Pajewski TN, Turner R, Nguyen TA, Smith A, et al. Exhaled breath condensate pH is a robust and reproducible assay of airway acidity. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:889–94. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00038803. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.03.00038803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roca O, Gómez-Ollés S, Jesús Cruz M, Muñoz X, Griffiths MJD, Masclans JR. Effects of salbutamol on exhaled breath condensate biomarkers in acute lung injury: prospective analysis. Crit Care. 2008;12:R72. doi: 10.1186/cc6911. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/cc6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Syslová K, Kačer P, Vilhanová B, Kuzma M, Lipovová P, Fenclová Z, et al. Determination of cysteinyl leukotrienes in exhaled breath condensate: Method combining immunoseparation with LC–ESI-MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879:2220–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.06.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Debley JS, Hallstrand TS, Monge T, Ohanian A, Redding GJ, Zimmerman JJ. Methods to improve measurement of cysteinyl leukotrienes in exhaled breath condensate from subjects with asthma and healthy controls. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1216–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.06.029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pleil JD, Hubbard HF, Sobus JR, Sawyer K, Madden MC. Volatile polar metabolites in exhaled breath condensate (EBC): collection and analysis. J Breath Res. 2008;2:026001. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/2/2/026001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1752-7155/2/2/026001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janicka M, Kubica P, Kot-Wasik A, Kot J, Namieśnik J. Sensitive determination of isoprostanes in exhaled breath condensate samples with use of liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2012;893–894:144–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.03.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoffmann HJ, Tabaksblat LM, Enghild JJ, Dahl R. Human skin keratins are the major proteins in exhaled breath condensate. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:380–4. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00059707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00059707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Effros RM, Casaburi R, Su J, Dunning M, Torday J, Biller J, Shaker R. The Effects of volatile salivary acids and bases on exhaled breath condensate pH. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:386–92. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1059OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200507-1059OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gessner C, Scheibe R, Wotzel M, Hammerschmidt S, Kuhn H, Engelmann L, et al. Exhaled breath condensate cytokine patterns in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2005;99:1229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.02.041. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2005.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varnai Veda M, Ljubičić Čalušić A, Prester Lj. Exhaled breath condensate pH in adult Croatian population without respiratory disorders: how healthy a population should be to provide normative data? Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 2009;60:87–97. doi: 10.2478/10004-1254-60-2009-1897. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/10004-1254-60-2009-1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vlašić Ž, Dodig S, Čepelak I, Topić RZ, Živčić J, Nogalo B, Turkalj M. Iron and ferritin concentrations in exhaled breath condensate of children with asthma. J Asthma. 2009b;46:81–5. doi: 10.1080/02770900802513007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02770900802513007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banović S, Navratil M, Vlašić Ž, Topić Zrinski R, Dodig S. Calcium and magnesium in exhaled breath condensate of children with endogenous and exogenous airway acidification. J Asthma. 2011;48:667–73. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.599907. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2011.599907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montuschi P. Analysis of exhaled breath condensate in respiratory medicine: methodological aspects and potential clinical applications. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2007;1:5–23. doi: 10.1177/1753465807082373. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1753465807082373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Effros RM, Peterson B, Casaburi R, Su J, Dunning M, Torday J, et al. Epithelial lining fluid solute concentrations in chronic obstructive lung disease patients and normal subjects. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1286–92. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00362.2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00362.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janicka M, Kot-Wasik A, Kot J, Namiesnik J. Isoprostanes-Biomarkers of Lipid Peroxidation: Their Utility in Evaluating Oxidative Stress and Analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:4631–59. doi: 10.3390/ijms11114631. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijms11114631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glowacka E, Jedynak-Wasowicz U, Sanak M, Lis G. Exhaled eicosanoid profiles in children with atopic asthma and healthy controls. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48:324–35. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22615. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ppul.22615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Molina MA, Zhao W, Sankaran S, Schivo M, Kenyon NJ, Davis CE. Design-of-experiment optimization of exhaled breath condensate analysis using a miniature differential mobility spectrometer (DMS) Analytica Chimica Acta. 2008;628:155–61. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.09.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis CE, Bogan MJ, Sankaran S, Molina MA, Loyola BR, Zhao W, et al. Analysis of Volatile and Non-Volatile Biomarkers in Human Breath Using Differential Mobility Spectrometry (DMS) IEEE Sensors J. 2010;10:114–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2009.2033562. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brooks WM, Lash H, Kettle AJ, Epton MJ. Optimizing hydrogen peroxide measurement in exhaled breath condensate. Redox Rep. 2006;11:78–84. doi: 10.1179/135100006X101011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/135100006X101011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gerritsen WB, Zanen P, Bauwens AA, van den Bosch JM, Haas FJ. Validation of a new method to measure hydrogen peroxide in exhaled breath condensate. Respir Med. 2005;99:1132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.02.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Esther CR, Lazaar AL, Bordonali E, Qaqish B, Boucher RC. Elevated airway purines in COPD. Chest. 2011;140:954–60. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2471. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liang Y, Yeligar SM, Brown LA. Exhaled breath condensate: a promising source for biomarkers of lung disease. Sci World J. 2012:217518. doi: 10.1100/2012/217518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Motta A, Paris D, Melck D, de Laurentiis G, Maniscalco M, Sofia M, et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance-based meta-bolomics of exhaled breath condensate: methodological aspects. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:498–500. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00036411. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00036411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bayley DL, Abusriwil H, Ahmad A, Stockley RA. Validation of assays for inflammatory mediators in exhaled breathe condensate. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:943–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00081707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00081707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonzales-Reche LM, Musiol AK, Müller-Lux A, Kraus T, Göen T. Method optimization and validation for the simultaneous determination of arachidonic acid metabolites in exhaled breath condensate by liquid chromatography-electro-spray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2006;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-1-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1745-6673-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yager D. Airway wall liquid in health and disease. In: Bittar EE, editor. Pulmonary biology in health and disease. Springer-Verlag; New York, USA: 2002. pp. 250–64. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caffarelli C, Calcinai E, Rinaldi L, Povesi Dascola C, Terracciano L, Corradi M. Hydrogen peroxide in exhaled breath condensate in asthmatic children during acute exacerbation and after treatment. Respiration. 2012;84:291–8. doi: 10.1159/000341969. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000341969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Antus B, Barta I, Csiszer E, Kelemen K. Exhaled breath condensate pH in patients with cystic fibrosis. Inflamm Res. 2012;61:1141–7. doi: 10.1007/s00011-012-0508-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00011-012-0508-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Donnelly LE. Exhaled breath condensate:nitric oxide-related compounds. In Horvath, JC de Jongste eds. Exhaled bio-markers. Eur Respir Mon. 2010;49:207–16. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rava M, Varraso R, Decoster B, Huyvaert H, Le Moual N, Jacquemin B, et al. Plasma and exhaled breath condensate nitrite-nitrate level in relation to environmental exposures in adult in the EGEA study. Nitric Oxide. 2012;15:169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2012.06.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.niox.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lázár Z, Vass G, Huszár E, Losonczy G, Horváth I. Exhaled breath condensate: adenosine, ATP and other purines. In: Horvath, JC de Jongste eds, Exhaled biomarkers. Eur Respir Mon. 2010;49:183–95. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel K, Davis SD, Johnson R, Esther CR., Jr Exhaled breath condensate purines correlate with lung function in infants and preschoolers. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48:182–7. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22573. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ppul.22573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Montuschi P. Exhaled breath condensate: 8-isoprostane and eicosanoids In: Horvath, JC de Jongste eds, Exhaled biomarkers. Eur Respir Mon. 2010;49:196–206. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gessner C, Dihazi H, Brettschneider S, Hammerschmidt S, Kuhn H, Eschrich K, et al. Presence of cytokeratins in exhaled breath condensate of mechanical ventilated patients. Respir Med. 2008;102:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.08.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Niimi A, Nguyen LT, Usmani O, Mann B, Chung KF. Reduced pH and chloride levels in exhaled breath condensate of patients with chronic cough. Thorax. 2004;59:608–12. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.012906. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2003.012906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dodig S, Čepelak I, Vlašić Ž, Zrinski Topić R, Banović S. Urates in exhaled breath condensate of children with asthma. Lab Med. 2010;41:728–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1309/LMTA9ZE2RZ4USKNP. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carpagnano G, Barnes PJ, Francis J, Wilson N, Bush A, Kharitonov SA. Breath condensate pH in children with cystic fibrosis and asthma: a new noninvasive marker of airway inflammation? Chest. 2004;125:2005–10. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.6.2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.125.6.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Biernacki WA, Kharitonov SA, Barnes PJ. Increased leukotriene B4 and 8-isoprostane in exhaled breath condensate of patients with exacerbations of COPD. Thorax. 2003;58:294–8. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thorax.58.4.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carpagnano GE, Resta O, Foschino-Barbaro MP, Spanevello A, Stefano A, Di Gioia G, et al. Exhaled breath interleukine-6 and 8-isoprostane in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect of carbocysteine lysine salt monohydrate (SCMC-Lys) Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;28:169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.10.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hasan RA, Thomas J, Davidson B, Barnes J, Redy R. 8-I-soprostane in the exhaled breath condensate of children hospitalized for status asthmaticus. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:e25–8. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181dbeac6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181dbeac6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Corradi M, Folesani G, Andreoli R, Manini P, Bodini A, Piacentini G, et al. Aldehydes and glutathione in exhaled breath condensate of children with asthma exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:395–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-507OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200206-507OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bartoli ML, Novelli F, Costa F, Malagrinò L, Melosini L, Bacci E, et al. Malondialdehyde in exhaled breath condensate as a marker of oxidative stress in different pulmonary diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2011;2011:891752. doi: 10.1155/2011/891752. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2011/891752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carpagnano GE, Barnes PJ, Geddes DM, Hodson ME, Kharitonov SA. Increased leukotriene B4 and interleukin-6 in exhaled breath condensate in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1109–12. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-179OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200203-179OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rihak V, Zatloukal P, Chladkova J, Zimulova A, Havlinova Z, Chladek J. Nitrite in exhaled breath condensate as a marker of nitrossative stress in the airways of patients with asthma, COPD, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2010;24:317–22. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcla.20408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Formanek W, Inci D, Lauener RP, Wildhaber JH, Frey U, Hall GL. Elevated nitrite in breath condensates of children with respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:487–91. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00101202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.00101202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koutsokera A, Loukides S, Gourgoulianis KI, Kostikas K. Biomarkers in the exhaled breath condensate of healthy adults: mapping the path towards reference values. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:620–30. doi: 10.2174/092986708783769768. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/092986708783769768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vlašić V, Trifunović J, Čepelak I, Nimac P, Topić RZ, Dodig S. Urates in exhaled breath condensate of children with obstructive sleep apnea. Biochem Med. 2011;21:139–44. doi: 10.11613/bm.2011.022. http://dx.doi.org/10.11613/BM.2011.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chow S, Thomas PS, Malouf M, Yates DH. Exhaled breath condensate (EBC) biomarkers in pulmonary fibrosis. J Breath Res. 2012;6:016004. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/6/1/016004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1752-7155/6/1/016004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Corradi M, Gergelova P, Mutti A. Exhaled volatile organic compounds in nonrespiratory diseases. In: Horvath I, De Jongste JC, editors. Exhaled Biomarkers. Eur Respir Mon. 2010;49:141–51. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Antczak A, Ciebiada M, Pietras T, Piotrowski WJ, Kurmanowska Z, Górski P. Exhaled eicosanoids and biomarkers of oxidative stress in exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Med Sci. 2012;9:277–85. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.28555. http://dx.doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2012.28555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Łuczyñska M, Szkudlarek U, Dziankowska-Bartkowiak B, Waszczykowska E, Kasielski M, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, et al. Elevated exhalation of hydrogen peroxide in patients with systemic sclerosis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:274–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01138.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jöbsis Q, Raatgeep HC, Schellekens SL, Hop WC, Hermans PW, de Jongste JC. Hydrogen peroxide in exhaled air of healthy children: reference values. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:483–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020483. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.98.12020483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Borrill Z, Starkey C, Vestbo J, Singh D. Reproducibility of exhaled breath condensate pH in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:269–74. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00085804. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00085804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhao JJ, Shimizu Y, Dobashi K, Kawata T, Ono A, Yanagitani N, et al. The relationship between oxidativestress and acid stress in adult patients with mild asthma. J Invest Allergol Clin Immunol. 2008;18:41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gessner C, Hammerschmidt S, Kuhn H, Hoheisel G, Gillissen A, Sack U, et al. Breath condensate nitrite correlates with hyperinflation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2007;101:2271–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Csoma Zs, Kharitonov SA, Balint B, Bush A, Wilson NM, Barnes PJ. Increased leukotrienes in exhaled breath condensate in childhood asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1345–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-233OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200203-233OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zanconato S, Carraro S, Corradi M, Alinovi R, Pasquale MF, Piacentini G, et al. Leukotrienes and 8-isoprostane in exhaled breath condensate of children with stable and unstable asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.046. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Montuschi P, Ciabattoni G, Paredi P, Pantelidis P, du Bois MR, Kharitonov SA, et al. 8-Isoprostane as a biomarker of oxidative stress in interstitial lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1524–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9803102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9803102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Robroeks CM, Rosias PP, van Vliet D, Jöbsis Q, Yntema JB, Brackel HJ, et al. Biomarkers in exhaled breath condensate indicate presence and severity of cystic fibrosis in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:652–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Carpenter CT, Price PV, Christman BW. Exhaled breath condensate isoprostanes are elevated in patients with acute lung injury or ARDS. Chest. 1998;114:1653–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.6.1653. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.114.6.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Carpagnano GE, Kharitonov SA, Resta O, Foschino-Barbaro MP, Gramiccioni E, Barnes PJ. Increased 8-isoprostane and interleukin-6 in breath condensate of obstructive sleep apnea patients. Chest. 2002;122:1162–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.4.1162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.122.4.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shahid SK, Kharitonov SA, Wilson NM, Bush A, Barnes PJ. Increased interleukin-4 and decreased interferon-γ in exhaled breath condensate of children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1290–3. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2108082. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.2108082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bucchioni E, Kharitonov SA, Allegra L, Barnes PL. High levels of interleukin-6 in the exhaled breath condensate in patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2003;97:1299–302. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.07.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Carpagnano GE, Resta O, Foscino-Brabaro MP, Gramiccioni E, Carpagnano F. lnterleukin-6 is increased in breath condensate of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2002;17:141–5. doi: 10.1177/172460080201700211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carpagnano GE, Kharitonov SA, Foschino-Barbaro MP, Resta O, Gramiccioni E, Barnes PJ. Increased inflammatory markers in the exhaled breath condensate of cigarette smokers. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:589–93. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00022203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.03.00022203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Barnes J. Future perspectives on exhaled biomarkers. In: Horvath I, de Jongste JC eds, Exhaled biomarkers. Eur Respir Mon. 2010;49:237–46. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sofia M, Maniscalco M, de Laurentiis G, Paris D, Melck D, Motta A. Exploring airway diseases by NMR-based metabonomics: a review of application to exhaled breath condensate. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:403260. doi: 10.1155/2011/403260. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2011/403260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]