Abstract

Aim:

The aim of study was to: 1) examine the relationship between ABO blood groups and extent of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with chronic coronary artery disease (CAD), 2) compare ABO blood groups distribution in CAD patients and general population, 3) examine possible differences in traditional risk factors frequency in CAD patients with different ABO blood groups.

Materials and methods:

In the 646 chronic CAD patients (72.4% males) coronary angiograms were scored by quantitative assessment using multiple angiographic scoring system, Traditional risk factors were self reported or measured by standard methods. ABO blood distribution of patients was compared with group of 651 healthy blood donors (74.6% males).

Results:

Among all ABO blood group patients there was no significant difference between the extent of coronary atherosclerosis with regard to all the three scoring systems: number of affected coronary arteries (P = 0.857), Gensini score (P = 0.818), and number of segments narrowed > 50% (P = 0.781). There was no significant difference in ABO blood group distribution between CAD patients and healthy blood donors. Among CAD patients, men with blood group AB were significantly younger than their pairs with non-AB blood groups (P = 0.008). Among CAD patients with AB blood group, males < 50 yrs were significantly overrepresented when compared with the non-AB groups (P = 0.003).

Conclusions:

No association between ABO blood groups and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis in Croatian CAD patients is observed. Observation that AB blood group might possibly identify Croatian males at risk to develop the premature CAD has to be tested in larger cohort of patients.

Keywords: ABO blood groups, atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease

Introduction

Several studies have suggested the possibility of ABO blood groups antigens to participate in pathogenesis of CAD. However, most of these studies reported a significant relationship between ABO blood groups and acute coronary events, especially acute myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death (1–3). As possible links between ABO blood groups and CAD pathogenesis authors emphasized increased prothrombotic state, higher prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and higher level of systemic inflammatory response revealed in patients with different ABO blood groups (4–6). Association between ABO blood groups and chronic CAD has been significantly less investigated.

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory process in which initiation and progression involve many cell types, such as: platelets, endothelial cells, monocytes, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells (7). Along with their expression on red blood cells, ABO antigens are highly expressed on the surface of endothelial cells and platelets (8). Moreover, blood group antigens are presented on key receptors controlling cell proliferation, adhesion, and motility (9). In this context it should be also mentioned that a series of GWAS have linked the ABO locus to circulating levels of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1, soluble P-selectin, soluble E-selectin, and angiotensin-converting enzyme, proteins which blood levels in humans correlate with increased risk of cardiovascular events (10,11). Also, some recent GWASs and their meta-analyses support this potential role for ABO genotypes in modulating circulating levels of total and LDL cholesterol, as well as phytosterols, established causal risk factors for atherosclerotic heart diseases (12). Overall, these associations with cardiovascular risk biomarkers suggest a complex role of ABO in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases.

Because initiation and progression of atherosclerosis involve interactions between activated endothelial cells, platelets, and inflammatory cells, we hypothesized that ABO antigens play an important role in cell-cell interactions, which goes along with the presence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, resulting in different progression of atherosclerosis, and consequently in different extent of CAD in patients with different ABO blood groups.

Previous studies on chronic CAD patients estimated extent of coronary atherosclerosis using single angiographic scoring system (13–16). So far, the only studies that have investigated the association between ABO blood groups and CAD in the Croatian population included patients with an acute myocardial infarction. Although results of first study confirmed the association of non-OO blood group genotypes with an increased risk of thrombosis, neither study demonstrated the association between particular ABO genotypes and an increased risk of myocardial infarction (17,18).

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the relationship between ABO blood groups and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with chronic CAD using multiple angiographic scoring system. Also, we aimed to compare ABO blood groups distribution in CAD patients and general population and to examine possible differences in traditional risk factors frequency in CAD patients with different ABO blood groups.

Materials and methods

Subjects

An observational study had been conducted from the beginning of 2009 until the end of 2010 in the Department of Cardiology, Split University Hospital Centre, Split, Croatia. In total, 646 patients with chronic CAD (468 [72.4%] males) undergoing coronary angiography had been consecutively enrolled. After noninvasive cardiology testing, coronary angiography was performed in patients with angina symptoms despite optimal medical treatment, as well as in patients who have experienced sudden cardiac arrest, in patients with a high pre-test probability of having left main or 3-vessel disease, in patients suspected for CAD who cannot undergo noninvasive testing and in patients with other indications, including patients with uncertain diagnosis on noninvasive testing, high-risk occupational requirements, clinically suspected nonatherosclerotic causes of ischemia or possible vasospasm with need for provocative testing, multiple hospital admissions, or an overriding patient desire for definitive diagnosis of the presence or absence of obstructive disease (19).

The distribution of ABO blood groups in patients were compared with the frequency of the blood groups in healthy controls, which consisted of 651 consecutive blood donors (486 [74.6%] males) with no symptoms and clinical signs of cardiovascular diseases, recruited in study during regular activities in the Department of Blood Transfusion, Split University Hospital Centre, Split, Croatia, from October until December 2010.

The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki after the approval from the local ethics committee had been obtained. The informed consent from the participants was not required due to the observational character of the study.

Collection of data

Residents in cardiology filled out the questionnaire on the demographic and clinical characteristics (age, sex, height, weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure), the patients self-reported presence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors (arterial hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, cigarette smoking), and values of laboratory parameters measured during the study (total cholesterol - TC, LDL cholesterol - LDL-C, HDL cholesterol - HDL-C, triglyceride - TG, glucose).

The presence of cardiovascular risk factors was defined as:

diabetes mellitus - fasting blood glucose > 6.9 mmol/L or non-fasting glucose level > 11 mmol/L, and/or use of antidiabetic medication;

arterial hypertension - systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg, or previous use of antihypertensive drugs;

hypercholesterolemia - TC > 4.5 mmol/L, LDL-C > 2.5 mmol/L, or previous use of lipid-lowering therapy;

hypertriglyceridemia – TG > 1.8 mmol/L;

overweight – BMI (weight/height 2) > 25 kg/m2;

cigarette smoking was categorized as non smoking or ever smoking; while

premature CAD was defined as a symptomatic CAD which emerged in men < 50 years and women < 55 years of age (19).

Laboratory methods

Blood samples had been collected in the morning, before angiographic procedure, after a fasting period of 12 hours. Serum, obtained from a blood collected in a vacuum tube, after centrifugation at 1500 × g for 10 minutes, had been used for TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, and glucose measurement. For ABO blood typing blood sample collected with EDTA had been used.

All laboratory tests were performed immediately after the sample reception in the Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Split University Hospital Center, Split, Croatia.

Plasma concentrations of glucose, TG, TC and HDL-C (after selective precipitation with Immuno AG, Vienna, Austria) were measured by standard enzymatic methods on a Beckman Coulter AU 640 (Beckman Coulter, Tokyo, Japan). LDL-C was calculated using Friedwald equation. If TG concentration was above 3 mmol/L, HDL-C and LDL-C were measured by direct immunoinhibition method (Olympus Diagnostica, Lismeehan, Ireland) and homogeneous assay (Randox Laboratories, Crumlin, United Kingdom), respectively.

ABO blood groups were determined in the Department of Blood Transfusion, Split University Hospital Centre, Split, Croatia, by commercially available hemagglutination techniques (Erytype S ABO Microplates, Biotest, Dreieich, Germany). Typing had been performed within 3 hours from sampling.

Methodology related to angiography

Selective coronary arteriography was carried out by Judkins technique using the femoral or radial route, viewing the results under fluoroscopy. The four cardinal epicardial vessels for assessment of stenotic lesions were LM, LAD, such as diagonal branches, RCx, obtuse marginal branches and the RCA. Angiographic scoring was performed by cardiologist who was blinded by the other studies result. For the purpose of this study, percentage of stenoses were graded on the RAO for left coronary injections and LAO for right coronary injections. Coronary angiograms were interpreted visually, analyzed in two orthogonal views, and scored by quantitative assessment of the coronary tree involving three criteria such as:

number of affected coronary arteries: 1-, 2- or 3-vessel disease;

modified GS which grades narrowing of the lumens of the coronary arteries as: grade 1 for 1–25% narrowing, 2 for 26–50% narrowing, 4 for 51–75% narrowing, 8 for 76–90% narrowing, 16 for 91–99% narrowing and 32 for total occlusion. These scores were then multiplied by a factor taking the importance of the lesion’s position in the coronary arterial tree into account: factor 5 for the LM coronary artery; 2.5 for the proximal LAD, proximal RCx or proximal RCA; 1.5 for the mid region of the LAD; 1 for the distal LAD or mid-distal region of the RCx or RCA; and 0.5 for one of the smaller branches. Total GS was expressed as the sum of the scores along entire coronary arteries (20);

number of segments of coronary arteries narrowed > 50%.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data (gender, coronary risk factors, affected vessels, ABO blood groups) were presented as counts or proportions (percentages) and quantitative data (age, laboratory parameters, number of affected vessels and segments narrowed > 50%, modified GS) were presented as mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD), and median with minimal to maximal range (min-max). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify the hypothesis of normal distribution of the quantitative variables. The differences between the frequency of ABO blood groups in CAD patients and healthy blood donors were tested using χ2-test. The difference between ABO blood groups were first assessed using the χ2-test for independent samples for categorical data and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for independent samples with Bonferroni or Tamhane’s T2 post-hoc multiple comparisons as appropriate for quantitative data. Demographic and clinical characteristics, frequency of coronary risk factors and extent and severity of atherosclerotic lesions on coronary arteries were then tested for one blood group (group X) versus other ABO blood groups comprised of non-X group (e.g. blood group AB vs. non-AB blood groups) using parametric Student’s t-test for independent samples or non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test for independent samples to determine the difference between quantitative variables and χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test for independent samples to calculate the difference between categorical data. All statistical tests were two-sided. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) and MedCalc Statistical Software (MedCalc Software, version 12.0, Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

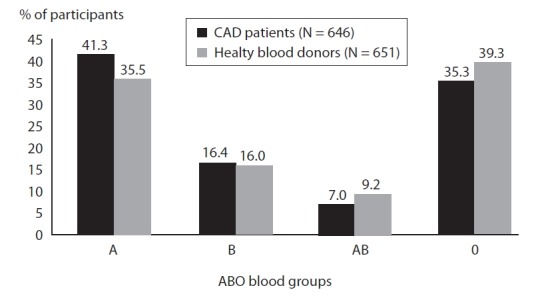

There was no significant difference in ABO group distribution between the group of CAD patients and healthy blood donors (Figure 1). No significant difference regarding gender structure and age was observed between patients and controls.

FIGURE 1.

Frequency of ABO blood groups in the group of CAD patients and healthy blood donors.

P values refers simultaneous comparison of all four blood groups; χ2-test.

Differences in incidence of self-reported traditional CAD risk factors between patients with different ABO blood groups were not significant. Namely, overweight, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia and cigarette smoking were present with similar frequencies in patients with all four blood groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patients’ characteristics according to ABO blood groups.

| Parameters |

ABO blood group

|

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (N = 267) | B (N = 106) | AB (N = 45) | O (N = 228) | ||

|

Demographics parameters (N [%] of pts.)

| |||||

| Males | 191 (71.5) | 84 (79.2) | 30 | 163 (71.5) | 0.331† |

| Age [years; median (min-max)] | 62 (37–84) | 61 (36–81) | 59 (41–77) | 64 (36–85) | 0.131‡ |

|

| |||||

| Coronary risk factors reported by patients (N [%] of pts.; mean ± SD) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.88 ± 3.67 | 28.06 ± 3.89 | 28.18 ± 4.58 | 28.12 ± 3.57 | 0.883‡ |

| 25–30 | 142 (53.2) | 57 (53.8) | 20 | 133 (58.3) | 0.539§ |

| > 30 | 66 (24.7) | 27 (25.5) | 15 | 58 (25.4) | 0.659§ |

| Arterial hypertension | 193 (72.3) | 70 (66.0) | 33 | 176 (77.2) | 0.194† |

| Diabetes mellitus | 122 (45.7) | 52 (49.1) | 16 | 102 (44.7) | 0.499§ |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 204 (76.4) | 82 (77.4) | 38 | 179 (78.5) | 0.810† |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 89 (33.3) | 45 (42.5) | 19 | 86 (37.7) | 0.325§ |

| Cigarette smoking | 84 (31.5) | 31 (29.2) | 15 | 57 (25.0) | 0.396§ |

| Premature CAD | |||||

| Males < 50 years | 25 (13.1) | 12 (14.3) | 8 | 11 (6.7) | 0 .012§ |

| Females < 55 years | 18 (23.7) | 3 (13.6) | 3 | 9 (13.8) | 0.449§ |

|

| |||||

| Laboratory parameters (mean ± SD) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 7.11 ± 2.52 | 7.63 ± 3.05 | 6.75 ± 2.37 | 7.24 ± 2.73 | 0.225‡ |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.21 ± 1.24 | 5.11 ± 1.17 | 5.06 ± 1.07 | 5.08 ± 1.21 | 0.616‡ |

| LDL-cholesterol† (mmol/L) | 3.07 ± 1.03 | 2.27 ± 1.31 | 2.83 ± 0.83 | 2.97 ± 1.02 | 0.165‡ |

| HDL-cholesterol‡ (mmol/L) | 1.29 ± 0.48 | 1.17 ± 0.30 | 1.27 ± 0.32 | 1.21 ± 0.33 | 0 .026‡ |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.77 ± 1.03 | 2.13 ± 1.36 | 1.89 ± 0.95 | 1.87 ± 1.28 | 0.065‡ |

CAD – coronary artery disease; LDL-cholesterol – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-cholesterol – high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

P – values refers simultaneous comparison of all four blood groups.

χ2-test

ANOVA

Fisher’s exact test

P values lower than level of significance are distinguished by bolding.

In analyzing differences in values of traditionally risk factors measured during the study (Table 1), the significantly lower HDL-C level was observed in CAD patients with blood group B. Differences in values of glucose, TC, LDL-C and TG did not reach the level of statistical significance. Significantly more males below 50 years were observed among CAD patients with blood group AB (Table 1).

Among CAD patients, men with blood group AB were significantly younger than their pairs with non-AB blood groups (60 ± 10 vs. 65 ± 10 yrs; P = 0.008). Also, in CAD patients with AB blood group, males younger than 50 years were overrepresented (36.7% vs. 15.6%; P = 0.003). The other differences in demographic and laboratory parameters were not of statistical significance.

Differences in the extent of coronary atherosclerosis between ABO blood groups patients with regard to all three scoring systems were not significant (Table 2). In all blood groups the most frequently affected coronary artery was LAD, followed by RCA and RCx. Also, the same sequence was observed with regard to extent of coronary atherosclerosis expressed in GS and number of > 50% stenoses, with the most prominent changes on the LAD.

TABLE 2.

Coronarography scoring according to ABO blood groups

| Coronary arteries |

ABO blood group

|

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (N = 267) | B (N = 106) | AB (N = 45) | O (N = 228) | ||

|

No. of affected vessels (mean ± SD)

| |||||

| 2.13 ± 1.10 | 2.09 ± 1.09 | 2.09 ± 1.04 | 2.19 ± 1.10 | 0.857† | |

|

| |||||

| Affected vessels (N [%] of pts.) | |||||

|

| |||||

| LM | 74 (27.7) | 23 (21.7) | 12 | 53 (23.2) | 0.552‡ |

| LAD | 213 (79.8) | 82 (77.4) | 35 | 183 (80.3) | 0.930§ |

| RCx | 163 (61.0) | 66 (62.3) | 24 | 152 (66.7) | 0.315§ |

| RCA | 190 (71.2) | 74 (69.8) | 35 | 162 (71.1) | 0.790§ |

|

| |||||

| Modified Gensini score (mean±SD) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Total | 63.13 ± 58.97 | 59.99 ± 59.27 | 54.17 ± 60.83 | 61.95 ± 63.02 | 0.818† |

| LAD | 22.92 ± 26.53 | 23.52 ± 29.29 | 15.22 ± 19.91 | 23.25 ± 27.35 | 0.299† |

| RCx | 12.81 ± 19.96 | 11.25 ± 16.43 | 13.19 ± 21.78 | 13.87 ± 21.82 | 0.745† |

| RCA | 21.80 ± 29.37 | 22.27 ± 29.06 | 19.42 ± 26.59 | 21.15 ± 29.35 | 0.948† |

|

| |||||

| No. of segments narrowed > 50% (mean ± SD) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Total | 2.21 ± 1.97 | 2.09 ± 1.95 | 2.02 ± 1.91 | 2.29 ± 2.14 | 0.781† |

| LAD | 0.82 ± 0.87 | 0.76 ± 0.88 | 0.62 ± 0.75 | 0.83 ± 0.89 | 0.475† |

| RCx | 0.58 ± 0.83 | 0.58 ± 0.77 | 0.51 ± 0.70 | 0.58 ± 0.80 | 0.962† |

| RCA | 0.71 ± 0.82 | 0.71 ± 0.89 | 0.78 ± 0.95 | 0.82 ± 0.94 | 0.565† |

LM – left main; LAD – left anterior descending coronary artery; RCx – circumflex coronary artery; RCA – right coronary artery.

P – values refers simultaneous comparison of all four blood groups.

ANOVA

Fisher’s exact test

χ2-test.

Discussion

The present study did not show any relationship between ABO blood groups and extent of atherosclerotic lesion of coronary arteries in Croatian patients with chronic CAD. It did not also reveal significant differences in ABO blood group distribution between CAD patients and healthy blood donors, or significant differences in frequency of traditional coronary risk factors in CAD patients with different ABO blood groups.

Despite numerous studies on the relationship between ABO blood groups and CAD, the link between these entities is still unclear. Most of these studies investigated the relationship between ABO blood groups and acute forms of CAD (1–3,6,17). The higher frequency of CAD patients with non-O blood groups suggested a protective anti-atherogenic effect of the blood group O (6,13). Moreover, association between increased risk for arterial and venous thromboembolic events, intermittent claudications and cerebral ischemia in patients with non-O blood groups and over-representing of the patients with blood group O in patients with inherited bleeding tendencies have further strengthen this thinking (21–23). Recently, He et al. reported that in cohort with total number of participants exceeds 90,000, those individuals with non-O blood group had an age-adjusted hazard ratio for risk of developing CAD. A meta-analysis of other cohorts which include over 114,000 participants, also showed significant pooled relative CAD risk in non-O blood group patients. Among them, those with O blood group were significantly less likely to CAD development in comparison with particular non-O blood groups (24).

However, some authors reported opposite observations. For example, Mitchell showed that the rate of cardiovascular mortality was increased in towns with a higher prevalence of blood group O (3). Furthermore, he concluded that cardiovascular disease might be more lethal in subjects with blood group O and that differences in blood group O distribution in different parts of Britain might provide an explanation for the geographic variation in ischemic heart disease (3).

Finally, in accordance with our results, some reports revealed that there is no relationship between ABO blood groups and CAD, denying the pathophysiological link between these entities (17,25,26).

Until date, only several studies have investigated possible relationship between angiographycally determined atherosclerotic changes in stable CAD and ABO blood groups (13–16). In Polish population advanced atherosclerosis of coronary arteries in non-O cardiac bypass surgery patients has been described. Authors found that there is significantly more frequent left main stenoses in patients with group A, and single-vessel disease in patients with blood group AB (15). In Hungarians who underwent coronary angiography, it has been observed that blood group A predominates among patients with positive coronarography, while blood group O was less frequent except in Hungarian population (16). In patients from Northern Finland, undergoing coronary artery by-pass grafting surgery, blood group B was associated with a higher angiographic score, but that findings had no implication on postoperative course (14). To the best of our knowledge, there is no study about possible association between ABO blood groups and extent of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with chronic CAD, estimated according to multiple scoring systems that were applied in our study. In that context, it is important that our results did not confirm the hypothesis, suggesting no association between ABO blood groups and extent of coronary atherosclerosis in Croatian CAD patients.

Also, in our study there was no difference in distribution of the ABO blood groups between CAD patients and healthy blood donors. Moreover, ABO blood groups distribution in both groups were similar with that revealed in the general Croatian population (17,18).

Some authors reported different frequency of the traditional cardiovascular risk factors in CAD patients with different ABO blood groups. In the Brazilians, patients with blood group A were younger than patients with other blood groups, while in the Lithuanians has been observed significantly higher incidence of blood group B in women younger than 45 years suffering from coronary atherosclerosis (27,28). Also, it has been reported that non-O blood groups were significantly associated with both family history and hypercholesterolemia (13). In our study, it was observed that differences in frequency of traditionally cardiovascular risk factors between ABO blood groups were decreased HDL-C level in patients with blood group B and significantly younger age of men with blood group AB. It is possible, therefore, to conclude that AB blood group might possibly identify Croatian males at risk to develop the premature CAD. On the other hand, it also revealed that difference in the values of HDL-C did not have any clinical implications.

However, our results do not exclude the possible association between ABO blood groups and acute coronary events. Although coronary angiography is the standard for evaluating the extent and severity of CAD, it does not demonstrate the overall of atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary artery wall, or its activity and rupture tendency which is the predisposition for the development of acute coronary events (7). It is possible that ABO antigens regain higher impact on the pathogenesis of acute coronary syndromes (unstable angina pectoris, acute myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death) (1–3). In addition to this argument, results of previous studies have shown that there are significantly higher absolute levels of von Willebrand factor in patients with acute coronary syndrome in relation to levels of this factor in stable CAD patients (6). It is plausible that ABO modulation of von Willebrand factor related thrombosis accounts for the ABO association with acute cardiovascular events. Also, ABO antigens are known to be carried by several platelet glycoproteins, and platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule, which may also act as potential modulators of the ABO blood groups association with arterial thrombosis and acute cardiovascular events (10,29). However, the widespread clinical usefulness of GWASs, including that for ABO locus, is limited by paradox relates to the highly significant probability values reported for common disease variants despite very small effect sizes, which required further studies in order to define the clinical and therapeutic possibilities (30).

The limitations of our study are related to the type of study, which is observational in nature. Furthermore, lack of information on CAD risk factors in control group, because in this article control group had been used mainly in the describing of blood group distribution in general population and chronic CAD Croatian patients. The small sample of patients, especially in AB blood group, could influence on observation that AB blood group may be possible marker of CAD precocity in younger Croatian population. Finally, ABO blood typing in the study did not rely on molecular techniques, as in many studies mentioned in discussion.

In conclusion, results of our study suggest no association between ABO blood groups antigens and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis in Croatian patients with chronic CAD. Observation that AB blood group might possibly identify Croatian males at risk to develop the premature CAD should be tested in the larger prospective cohort study.

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.von Beckerath N, Koch W, Mehilli J, Gorchakova O, Braun S, Schömig A, et al. ABO locus O1 allele and risk of myocardial infarction. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2004;15:61–7. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200401000-00010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001721-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee HF, Lin YC, Lin CP, Wang CL, Chang CJ, Hsu LA. Association of blood group A with coronary artery disease in young adults in Taiwan. Intern Med. 2012;51:1815–20. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7173. http://dx.doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michell JR. An association between ABO blood group distribution and geographical differences in death-rates. Lancet. 1977;1:295–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91838-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736-(77)91838-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Donnell J, Laffan MA. The relationship between ABO histo-blood group, factor VIII and von Willebrand factor. Transfus Med. 2001;11:343–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2001.00315.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3148.2001.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrison RJ, Havlik RJ, Harris RB, Feinleib M, Kannel WB, Padgett SJ. ABO blood group and cardiovascular disease: the Framingham study. Atherosclerosis. 1976;25:311–8. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(76)90036-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0021-9150(76)90036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray KK, Francis S, Crossman DC. Measurement of plasma von Willebrand factor in acute coronary syndromes and the influence of ABO blood group status. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:2053–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00965.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Libby P. Inflamation in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2045–51. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179705. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eastlund T. The histo-blood group ABO system and tissue transplantation. Transfusion. 1998;38:975–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.381098440863.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.381098440863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenwell P. Blood group antigens: molecules seeking a function? Glycoconj J. 1997;14:159–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1018581503164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1018581503164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiechl S, Pare G, Barbalic M, Oi L, Dupuis J, Dehghan A, et al. Association of variation at the ABO locus with circulating levels of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1, soluble P-selectin, and soluble E-selectin: a meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011;4:681–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.960682. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.960682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung CM, Wang RY, Chen JW, Fann CS, Leu HB, Ho HY, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies new loci for ACE activity: potential implications for response to ACE inhibitor. Pharmacogenomics J. 2010;10:537–44. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/tpj.2009.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466:707–13. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpeggiani C, Coceani M, Landi P, Michelassi C, L’Abbate A. ABO blood group alleles: A risk factor for coronary artery disease. An angiographic study. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:461–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.03.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biancari F, Satta J, Pokela R, Juvonen T. ABO blood group distribution and severity of coronary artery disease among patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery in Northern Finland. Thromb Res. 2002;108:195–6. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00003-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0049-3848(03)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slipko Z, Latuchowska B, Wojtkowska E. Body structure and ABO and Rh groups in patients with advanced arteriosclerosis of coronary heart disease after aorto-coronary by-pass surgery. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 1994;91:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarján Z, Tonelli M, Duba J, Zorándi A. Correlation between ABO and RH blood groups, serum cholesterol and ischemic heart disease in patients undergoing coronarography. Orv Hetil. 1995;136:767–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jukic I, Bingulac-Popovic J, Dogic V, Babic I, Culej J, Tomicic M, et al. ABO blood groups and genetic risk factors for thrombosis in Croatian population. Croat Med J. 2009;50:550–8. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2009.50.550. http://dx.doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2009.50.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jukic I, Bingulac-Popovic J, Dogic V, Hecimovic A, Babic I, Batarilo I, et al. Evaluation of ABO blood groups as a risk factor for myocardial infarction. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:464–5. doi: 10.2450/2012.0065-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, Daley J, Deedwania PC, Douglas JS, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 Guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina – summary article: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (Committee on the management of patients with chronic stable angina) Circulation. 2003;107:149–58. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047041.66447.29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000047041.66447.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gensini GG. A more meaningful scoring system for determing the severity of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:606. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80105-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149-(83)80105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu O, Bayoumi N, Vickers MA, Clark P. ABO (H) blood groups and vascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:62–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02818.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hørby J, Gyrtrup HJ, Grande P, Vestergaard A. Relation of serum lipoproteins and lipids to the ABO blood groups in patients with intermittent claudication. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1989;30:533–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark P, Meiklejohn DJ, O’Sullivan A, Vickers MA, Greaves M. The relationships of ABO, Lewis and Secretor blood groups with cerebral ischemia of arterial origin. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2105–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01535.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01535.x, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He M, Wolpin B, Rexrode K, Manson JE, Rimm E, Hu FB, et al. ABO blood risk and risk of coronary heart disease in two prospective cohort studies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2314–20. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248757. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill JC, Endres-Brooks J, Bauer PJ, Marks WJ, Jr, Montgomery RR. The effect of ABO blood group on the diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Blood. 1987;69:1691–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amirzadegan A, Salarifar M, Sadeghian S, Davoodi G, Darabian C, Goodarzynejad H. Correlation between ABO blood groups, major risk factors, and coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:256–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.06.058. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cesena FH, da Luz PL. ABO blood group and precocity of coronary artery disease. Thromb Res. 2006;117:401–2. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.03.023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stakisaitis D, Maksvytis A, Benetis R, Viikmaa M. Coronary atherosclerosis and blood groups of ABO system in women (own data and review) Medicina (Kaunas) 2002;38:230–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cadroy Y, Sakariassen J, Charlet JP, Thalamas C, Boneu B, Sie P. Role of 4-platelet membrane glycoprotein polymorphism on experimental arterial thrombus formation in men. Blood. 2001;10:3159–61. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood.V98.10.3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H, Mooney CJ, Reilly MP. ABO Blood Groups and Cardiovascular Diseases [Electronic version] International Journal of Vascular Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/641917. Accessed September 13, 2013, from http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/641917. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/641917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]